Abstract

The National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) is a primary source of information on the changing health of the U.S. population over the past four decades. The full potential of NHIS data for analyzing long-term change, however, has rarely been exploited. Time series analysis is complicated by several factors: large numbers of data files and voluminous documentation; complexity of file structures; and changing sample designs, questionnaires, and variable-coding schemes. We describe a major data integration project that will simplify cross-temporal analysis of population health data available in the NHIS. The Integrated Health Interview Series (IHIS) is a Web-based system that provides an integrated set of data and documentation based on the NHIS public use files from 1969 to the present. The Integrated Health Interview Series enhances the value of NHIS data for researchers by allowing them to make consistent comparisons across four decades of dramatic changes in health status, health behavior, and healthcare.

The National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) is a leading source of data on the health of the American population.1 These data are used to monitor the health of the U.S. population,2 track progress toward Healthy People 2010 objectives ,3 and evaluate the quality of healthcare in the U.S.4 The rich array of data has also been valuable for a broad range of population health research. NHIS data allow examination of conditions such as cancer, diabetes, hypertension, asthma, and functional limitations. Data are also available on preventive care utilization, including cancer screening5-7 and immunization,8, 9 and on health behaviors such as diet,10, 11 physical activity,12-14 and tobacco use.15-17 A wealth of sociodemographic information permits examination of social disparities in access to care, morbidity, and mortality.18-22 Moreover, pooling multiple years of data provides sufficient sample size for analysis of subpopulations of interest.23, 24

The NHIS is the longest-running U.S. health survey, with annual microdata from 1963 to the present. This broad chronological coverage makes these data uniquely suited for studying changes in health over time. Yet, cross-temporal analyses of these important data have been uncommon, particularly by researchers outside the National Center for Health Statistics.25 Use of NHIS data has increased in recent years, most notably after the 2001 release of data files on the Internet. However, use of these complex data in time-series analyses remains rare. The purpose of this paper is to introduce this resource to the epidemiologic community.

The Data Integration Project

The Integrated Health Interview Series (IHIS) project is a well-documented cross-sectional time series based on the National Health Interview Survey. We make these data freely available through a user-friendly Web-based data dissemination system (available at http://www.ihis.us) to facilitate informed analysis of this valuable source of information about the nation’s health. The IHIS builds on the model of the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS), a harmonized set of U.S. Census data from 1850 to 2000.26 There are three components to the IHIS data integration project: 1) harmonization, 2) documentation, and 3) dissemination.

Harmonization

Discontinuities in National Health Interview Survey variables complicate analysis of change over time. Harmonization is the process of taking original variables with different coding schemes and creating a new variable that is comparable over time. The “translation table” is the foundation of this harmonization work. It is a tool (in spreadsheet format) for laying out the various coding schemes for each year and then aligning the coding schemes into a single integrated scheme.

In some cases, the original variables are completely or nearly compatible, and recoding them into a common classification is relatively straightforward. For example, marital status is nearly identical over time, although with small differences. Table 1 shows selected sections of the marital status translation table. In the first 2 columns, the final integrated coding scheme and value labels are listed with the original (unharmonized) codes for each year in the remaining columns.

Table 1.

Portions of a translation table using a simple coding scheme for harmonization for Legal marital status (MARSTAT)

| IHIS Code | IHIS Label | 1969 NHIS Code | 1982 NHIS Code | 2004 NHIS Code |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Not in universe | 0 = under 17 years | 0 = under 14 years | Blank = under 14 years |

| 1 | Married | 1 = Married | 3 = Married | |

| 2 | Married - Spouse present | 1 = Married - Spouse in household | ||

| 3 | Married - Spouse not in household | 2 = Married - Spouse not in household | ||

| 4 | Married - Spouse in household unknown | |||

| 5 | Widowed | 2 = Widowed | 3 = Widowed | 5 = Widowed |

| 6 | Divorced | 4 = Divorced | 4 = Divorced | 2 = Divorced |

| 7 | Separated | 5 = Separated | 5 = Separated | 1 = Separated |

| 8 | Never married | 3 = Never married | 6 = Never married | 4 = Single/never married |

| 9 | Unknown marital status | 7 = Unknown | 9 = Unknown marital status |

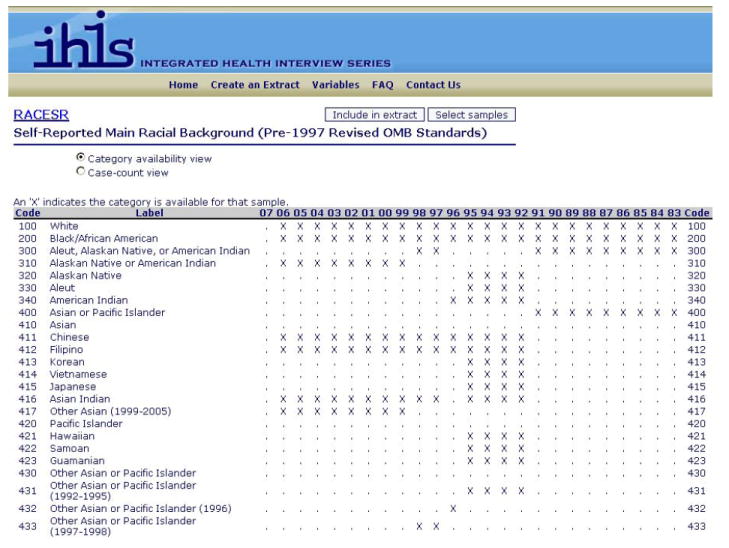

For other variables, it is impossible to construct a single uniform classification without losing information. Some years provide more detail than others, and using the “lowest common denominator” of all years would discard important information. In these cases, we construct composite coding schemes. The first digit(s) of the code provide information available across all years. The next digits provide additional information available in a broad subset of years. For example, the variable for self-reported main race uses a variety of coding schemes over time. Table 2 shows selected sections of the translation table, and eFigure 1 (available with the online version of this article) shows a partial screenshot of the IHIS codes available for this variable. The utility of composite coding can be seen in the case of Asian or Pacific Islanders. Codes 400 through 430 are all sub-classifications of this group. Using the first digit (4) provides the broadest comparable grouping over time. Using the second digit distinguishes Asian (41) from Pacific Islander (42). Researchers interested in even finer distinctions can use the 3-digit values.

Table 2.

Portions of a translation table using a composite coding scheme for harmonization for Self-Reported Main Racial Background (RACESR).

| IHIS Code | IHIS Label | 1978 NHIS Code | 1992 NHIS Code | 2000 NHIS Code |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | White | 4 = White | 1 = White | 1 = White |

| 200 | Black/African American | 3 = Black | 2 = Black | 2 = Black/African American |

| 300 | Aleut, Alaskan Native, or American Indian | 1 = Aleut, Eskimo, or American Indian | 3 = Indian (American), Alaska Native | |

| 320 | Alaskan Native | 4 = Eskimo | ||

| 330 | Aleut | 5 = Aleut | ||

| 340 | American Indian | 3 = Indian (American) | ||

| 400 | Asian or Pacific Islander | 2 = Asian/Pacific Islander | ||

| 410 | Asian | |||

| 411 | Chinese | 6 = Chinese | 10 = Chinese | |

| 412 | Filipino | 7 = Filipino | 11 = Filipino | |

| 413 | Korean | 9 = Korean | ||

| 414 | Vietnamese | 10 = Vietnamese | ||

| 415 | Japanese | 11 = Japanese | ||

| 416 | Asian Indian | 12 = Asian Indian | 9 = Asian Indian | |

| 417 | Other Asian | 15 = Other Asian | ||

| 420 | Pacific Islander | |||

| 421 | Hawaiian | 8 = Hawaiian | ||

| 422 | Samoan | 13 = Samoan | ||

| 423 | Guamanian | 14 = Guamanian | ||

| 430 | Other Asian or Pacific Islander | 15 = Other API | ||

| 500 | Other race | 5 = Another group not listed | 16 = Other race | 16 = Other Race |

| 600 | Multiple race, no primary race selected | 6 = Multiple entry - unknown which is main race | 17 = Multiple race | 17 = Multiple race |

| 900 | Unknown | 7 = Unknown | 99 = Unknown |

eFigure 1.

IHIS screenshot of codes for self-reported main race (RACESR) showing composite coding.

Harmonization also allows us to address sample design discontinuities. We constructed the IHIS survey design variables to be usable when examining data from one year or from many years. We employed the concatenated design period pooling approach suggested by Korn and Graubard27 (p280) for pooling data from one survey over multiple years and sample designs. Strata and primary sampling unit (PSU) variables are constructed so researchers need do no additional recoding of these variables, regardless of which years of data are analyzed.

Documentation

The Integrated Health Interview Series provides documentation designed to enhance researchers’ ability to work with the data as a cross-sectional time series. Along with detailed descriptions of each variable, the IHIS also includes general documentation (such as user notes about the original NHIS source data, sample design and sampling weights) and guidance on analysis and variance estimation.

For each variable, we consulted the survey descriptions, codebooks, questionnaires, and interviewer instructions for each year, as well as documented discussions of survey methodology, concepts, and sample selection.28-33 We reorganized this information by putting all essential facts relating to one variable over time into a single narrative.

Variable-specific documentation covers the meaning of a variable, years available, universe definitions, codes, and frequency distributions. We also provide discussions of cross-temporal comparability for each variable. We have noted potential problems in combining multiple years of the variable and offer suggestions for maximizing comparability and for choosing appropriate weights. The variable descriptions also reference related variables, with information accessible via hyperlinks. When variables cannot be fully harmonized, the documentation explains the limitations of comparability.

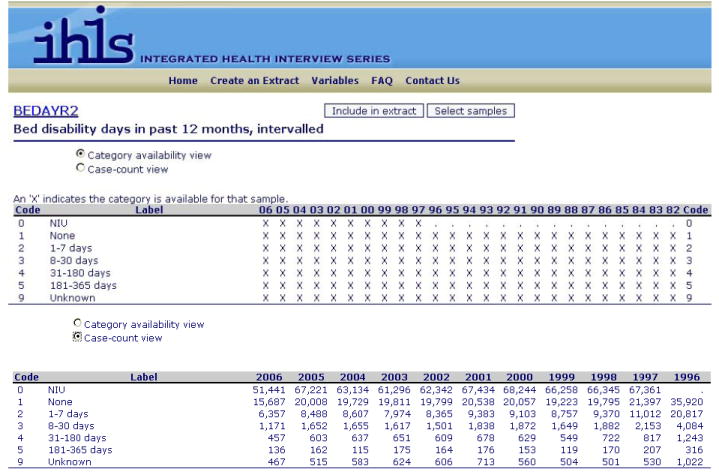

Response category codes and frequencies can be accessed from the variable availability grid or from a link on each variable description. Codes and frequencies are displayed so researchers can see which categories are represented in each available year. Codes can also be viewed in “case count” format, with unweighted sample size for each response category displayed by year. eFigure 2 in the online appendix shows both the category availability view and the case count views for one IHIS variable.

eFigure 2.

IHIS screenshot of codes and frequencies for categories of bed disability days (BEDAYR2).

Dissemination

User-friendly data dissemination is an integral component of this effort. We distribute these data and documentation through a Web-based data access system that is available free of charge (http://www.ihis.us). For each data extract, the researcher specifies the file type (hierarchical or rectangular), data format (SAS, Stata, SPSS), years to be included, and variables for analysis. The researcher can provide a short description of the extract, which is numbered and displayed for future reference in the researcher’s personal download history (accessible at every subsequent log-in). When the data extract is ready for download, an e-mail is sent to alert the researcher.

For each extract submitted, the researcher downloads a compressed ASCII data file, an extract-specific codebook, and a command file with syntax to convert the ASCII data to the preferred file format. At any time, the researcher can return to the personalized data download Web page to revise or resubmit a previously-created extract request. Users who encounter difficulties can e-mail IHIS user support for assistance.

Project Status and Future Plans

The Integrated Health Interview Series currently consists of more than 1,000 integrated variables selected from NHIS data files for 1969 to the present. However, this is only a fraction of the total variables available in NHIS. Additional variables are steadily being added. Furthermore, users can link additional variables from the original NHIS public use files to an IHIS data extract. A user note with guidance on linking, as well as syntax files for merging, are provided on the website.

IHIS data can be used by population health researchers in numerous ways. The data can document trends over time in the incidence of conditions such as diabetes, the prevalence of health behaviors such as smoking, or disparities in cancer screening. Exposure-outcome relationships such as socioeconomic indicators (e.g., education, income, or poverty status) and cause-specific mortality can be examined for the years 1986 to 2000. Pooling multiple years of IHIS data can provide sufficient sample size to study small subgroups such as American Indians, farmers, or new immigrants.

We are making available links between the original NHIS survey text and each IHIS variable description. We are extending the time series backward by including new public use files for 1963 to 1968 (these files are currently being created by NCHS staff). We are also in the process of developing new features for the Web site, including on-line tabulation and a search engine to help users efficiently locate variables.

Old health survey data are not simply of historical interest; rather, they are essential tools for understanding the dynamics of population health. Our goal with IHIS is to reduce barriers to cross-temporal analysis using four decades of NHIS data. These integrated, well-documented, and easily accessible health data provide an important new data resource for epidemiologic and population health research.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: Supported by Grant Number R01HD046697 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Footnotes

e Supplemental material for this article is available with the online version of the journal at www.epidem.com

References

- 1.Gentleman JF, Pleis JR. The National Health Interview Survey: an overview. Eff Clin Pract. 2002;5(3 Suppl):E2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams PF, Dey AN, Vickerie JL. Summary health statistics for the U.S. population: National Health Interview Survey, 2005. Vital Health Stat 10. 2007;10(233):1–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010. 2nd ed. With Understanding and Improving Health and Objectives for Improving Health. US Government Printing Office. 2 Available at: http://www.healthypeople.gov/document/

- 4.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2006 National Healthcare Quality Report. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2006. AHRQ Pub No 07-0013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calle EE, Flanders WD, Thun MJ, Martin LM. Demographic predictors of mammography and Pap smear screening in US women. Am J Public Health. 1993;83(1):53–60. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hiatt RA, Klabunde C, Breen N, Swan J, Ballard-Barbash R. Cancer screening practices from National Health Interview Surveys: past, present, and future. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(24):1837–1846. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.24.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swan J, Breen N, Coates RJ, Rimer BK, Lee NC. Progress in cancer screening practices in the United States: results from the 2000 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer. 2003;97(6):1528–1540. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dombkowski KJ, Lantz PM, Freed GL. The need for surveillance of delay in age-appropriate immunization. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23(1):36–42. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pleis JR, Gentleman JF. Using the National Health Interview Survey: time trends in influenza vaccinations among targeted adults. Eff Clin Pract. 2002;5(3 Suppl):E3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thompson FE, Midthune D, Subar AF, McNeel T, Berrigan D, Kipnis V. Dietary intake estimates in the National Health Interview Survey, 2000: methodology, results, and interpretation. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105(3):352–363. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.12.032. quiz 487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patterson BH, Harlan LC, Block G, Kahle L. Food choices of whites, blacks, and Hispanics: data from the 1987 National Health Interview Survey. Nutr Cancer. 1995;23(2):105–119. doi: 10.1080/01635589509514367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmed NU, Smith GL, Flores AM, et al. Racial/ethnic disparity and predictors of leisure-time physical activity among U.S. men. Ethn Dis. 2005;15(1):40–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caspersen CJ, Christenson GM, Pollard RA. Status of the 1990 physical fitness and exercise objectives--evidence from NHIS 1985. Public Health Rep. 1986;101(6):587–592. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kruger J, Galuska DA, Serdula MK, Kohl HW., 3rd Physical activity profiles of U.S. adults trying to lose weight: NHIS 1998. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37(3):364–368. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000155434.87146.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilpin EA, Pierce JP. Demographic differences in patterns in the incidence of smoking cessation: United States 1950-1990. Ann Epidemiol. 2002;12(3):141–150. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00266-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee DJ, LeBlanc W, Fleming LE, Gomez-Marin O, Pitman T. Trends in US smoking rates in occupational groups: the National Health Interview Survey 1987-1994. J Occup Environ Med. 2004;46(6):538–548. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000128152.01896.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shopland DR, Brown C. Toward the 1990 objectives for smoking: measuring the progress with 1985 NHIS data. Public Health Rep. 1987;102(1):68–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cubbin C, LeClere FB, Smith GS. Socioeconomic status and injury mortality: individual and neighbourhood determinants. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000;54(7):517–524. doi: 10.1136/jech.54.7.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lowry R, Kann L, Collins JL, Kolbe LJ. The effect of socioeconomic status on chronic disease risk behaviors among US adolescents. Jama. 1996;276(10):792–797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaufman JS, Long AE, Liao Y, Cooper RS, McGee DL. The relation between income and mortality in U.S. blacks and whites. Epidemiology. 1998;9(2):147–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newacheck PW, Stein RE, Bauman L, Hung YY. Disparities in the prevalence of disability between black and white children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(3):244–248. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.3.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silver EJ, Stein RE. Access to care, unmet health needs, and poverty status among children with and without chronic conditions. Ambul Pediatr. 2001;1(6):314–320. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2001)001<0314:atcuhn>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brackbill RM, Cameron LL, Behrens V. Prevalence of chronic diseases and impairments among US farmers, 1986-1990. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;139(11):1055–1065. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McGee DL, Liao Y, Cao G, Cooper RS. Self-reported health status and mortality in a multiethnic US cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149(1):41–46. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mugge RH. The varied uses of health statistics. Public Health Rep. 1981;96(3):228–230. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruggles S, Sobek M, Alexander T, et al. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 3.0 [Machine-readable database] Minneapolis, MN: Minnesota Population Center [producer and distributor]; Available at: http://usa.ipums.org/usa/ [Google Scholar]

- 27.Korn EL, Graubard BI. Analysis of Health Surveys. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kovar MG, Poe GS. The National Health Interview Survey design, 1973-84, and procedures, 1975-83. Vital Health Stat 1. 1985;1(18):1–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Massey JT, Moore TF, Parsons VL, Tadros W. The 1985-94 NHIS sample design. Vital Health Stat 2. 1989;2(110):1–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Center for Health Statistics. National Health Interview Survey: research for the 1995-2004 redesign. Vital Health Stat 2. 1999;2(126):1–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Health interview survey 1957-1974. Vital Health Stat 1. 1975;Series 1(11):1–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khrisanopulo MP. Health Survey Procedure. Concepts, Questionnaire Development, and Definitions in the Health Interview Survey. Vital Health Stat 1. 1964;1(27):1–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Design and estimation for the National Health Interview Survey, 1995-2004. Vital Health Stat 2. 2000;2(130):1–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]