Abstract

The norepinephrine nucleus, locus ceruleus (LC), is activated by diverse stimuli and modulates arousal and behavioral strategies in response to these stimuli through its divergent efferent system. Afferents communicating information to the LC include excitatory amino acids (EAAs), corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), and endogenous opioids acting at μ-opiate receptors. Because the LC is also innervated by the endogenous κ-opiate receptor (κ-OR) ligand dynorphin and expresses κ-ORs, this study investigated κ-OR regulation of LC neuronal activity in rat. Immunoelectron microscopy revealed a prominent localization of κ-ORs in axon terminals in the LC that also contained either the vesicular glutamate transporter or CRF. Microinfusion of the κ-OR agonist (trans)-3,4-dichloro-N-methyl-N-[2-1-pyrrolidinyl)-cyclo-hexyl] benzeneacetamide (U50488) into the LC did not alter LC spontaneous discharge but attenuated phasic discharge evoked by stimuli that engage EAA afferents to the LC, including sciatic nerve stimulation and auditory stimuli and the tonic activation associated with opiate withdrawal. Inhibitory effects of the κ-OR agonist were not restricted to EAA afferents, as U50488 also attenuated tonic LC activation by hypotensive stress, an effect mediated by CRF afferents. Together, these results indicate that κ-ORs are poised to presynaptically inhibit diverse afferent signaling to the LC. This is a novel and potentially powerful means of regulating the LC–norepinephrine system that can impact on forebrain processing of stimuli and the organization of behavioral strategies in response to environmental stimuli. The results implicate κ-ORs as a novel target for alleviating symptoms of opiate withdrawal, stress-related disorders, or disorders characterized by abnormal sensory responses, such as autism.

Keywords: locus ceruleus, κ-opiate receptor, dynorphin, corticotropin-releasing factor, glutamate, morphine withdrawal

Introduction

The locus ceruleus (LC) innervates the entire neuraxis and is the primary source of forebrain norepinephrine (NE) (Swanson, 1976; Swanson and Hartman, 1976). LC neurons are activated by diverse sensory stimuli, visceral stimuli, and internal and environmental stressors (Foote et al., 1980; Aston-Jones and Bloom, 1981a; Abercrombie and Jacobs, 1987; Morilak et al., 1987; Svensson, 1987). Changes in the rate and/or pattern of LC discharge produced by these stimuli impact on the state of arousal and play a role in determining subsequent behavioral strategy (Berridge and Waterhouse, 2003; Aston-Jones and Cohen, 2005).

Neurochemically distinct afferents have been identified that convey specific modes of information to the LC. These include excitatory amino acids (EAAs), corticotropin releasing factor (CRF), and endogenous opioids (Aston-Jones et al., 1991; Van Bockstaele et al., 2001). EAA afferents mediate LC activation by certain sensory stimuli, including the well characterized activation by sciatic nerve stimulation and possibly auditory stimulation (Chiang et al., 1991; Ennis et al., 1992). LC neurons are also activated by non-noxious visceral stimuli and a role for EAA afferents in LC activation by bladder distention has been demonstrated (Page et al., 1992). Finally, LC activation elicited by naloxone-precipitated opiate withdrawal, which may contribute to the aversive aspects of this syndrome, is mediated in part via medullary EAA afferents (Rasmussen et al., 1990, 1991; Akaoka and Aston-Jones, 1991; Rasmussen, 1995).

Activation of the LC–NE system by stressors often occurs in parallel with the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis. CRF, the hypothalamic neurohormone that initiates the endocrine limb of the stress response (Vale et al., 1981), is one mediator of LC activation by certain stressors and has been demonstrated to be necessary for stress-elicited arousal (Valentino et al., 1991; Page et al., 1993; Curtis et al., 1997). In opposition, endogenous opioids acting at μ-opiate receptors (μ-ORs) are released with stress termination to inhibit the LC and facilitate the return to baseline activity (Curtis et al., 2001). The balance of these opposing influences is likely important in maintaining appropriate responses to stressors (Valentino and Van Bockstaele, 2001).

Recently, LC innervation by the κ-OR ligand, dynorphin, was identified (Reyes et al., 2007) and others have demonstrated κ-OR mRNA and protein in the LC (DePaoli et al., 1994; Mansour et al., 1994), suggesting that this system regulates LC activity. This is of particular interest as dynorphin and κ-ORs are implicated in stress-related disorders (Pliakas et al., 2001; Mague et al., 2003; McLaughlin et al., 2006a). Moreover, elevated κ-OR gene expression in the LC of Wistar-Kyoto (WKY) rats, a strain that has been used to model stress-related depression, suggests that κ-OR activation in this nucleus may have clinically relevant consequences (Pearson et al., 2006).

The present study used immunoelectron microscopy to elucidate the cellular localization of κ-ORs within the rat LC. Electrophysiological studies in anesthetized and unanesthetized rats identified the impact of activating κ-ORs in the LC. Together, these studies revealed a novel function for the κ-OR system in regulating afferent communication within the LC.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

Male Sprague Dawley rats (200–300 g; Taconic Farms or Charles River Laboratories) were housed three to a cage with food and water available ad libitum in a 12 h light/dark cycle. Rats were allowed to acclimatize for 7 d after arrival to the laboratory animal facility before beginning experiments. Care and use of animals was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (physiological experiments) and by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Thomas Jefferson University (electron microscopy experiments).

Electron microscopy.

Perfusion and collection of tissue was identical to our previous studies (Reyes et al., 2006). Sections were incubated 12–14 h in a mixture of either mouse anti vesicular glutamate transporter 1 (VGlut1; 1:500; Synaptic Systems) or guinea pig anti-CRF (1:1000; Peninsula Pharmaceuticals) and rabbit anti-κ-OR (1:500) in 0.1% BSA. After rinses, sections were incubated in biotinylated donkey anti-rabbit (1:400; Jackson ImmunoResearch) followed by a 30 min incubation in avidin-biotin complex (Vector Laboratories). κ-OR was visualized using 22 mg of 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB; Sigma-Aldrich) dissolved in 0.1 m phosphate buffer (PB). VGlut1 was visualized using silver intensification of a goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated to 1 nm gold particles (1:50; GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences) after the DAB reaction. To avoid any bias in labeling, some sections were reversed labeled so that κ-OR was visualized using an immunogold reaction and VGlut was visualized using immunoperoxidase. For visualization of CRF and κ-OR, CRF immunoreactivity was visualized using DAB, whereas κ-OR was visualized using silver intensification of a goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to 1 nm gold particles (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences). In some sections, the processing was reversed such that CRF was visualized using an immunogold reaction, and κ-OR was visualized using immunoperoxidase. Control sections for each experiment were run in parallel with the primary antibody omitted. No detectable immunoreactivity was observed in the absence of the primary antibody. After intensification, tissue sections were rinsed and incubated in 2% osmium tetroxide (Electron Microscopy Sciences) in 0.1 m PB for 1 h, washed in 0.1 m PB, dehydrated in an ascending series of ethanol followed by propylene oxide, and flat embedded in Epon 812 (Electron Microscopy Sciences). Thin sections (50–80 nm) were cut with a diamond knife (Diatome), collected on copper mesh grids, and examined with an electron microscope (Morgagni; FEI). Digital images were captured using the Advance Microscopy Techniques advantage HR/HR-B CCD camera system. Figures were assembled and adjusted for brightness and contrast in Adobe Photoshop.

The classification of identified cellular elements was based on the ultrastructural descriptions of Peters et al. (1991). Dendrites usually contained endoplasmic reticulum and were postsynaptic to axon terminals. Axon terminals were differentiated from preterminal axons by the presence of abundant synaptic vesicles and were at least 0.3 μm in diameter. Synaptic specializations were defined as Gray's type I or asymmetric (Gray, 1959) if the axon terminal showed a restricted zone of parallel membranes with slight enlargement of the intercellular space and an associated thick postsynaptic density. In contrast, symmetric synapses had thin densities (Gray's type II) (Gray, 1959) both presynaptically and postsynaptically. If a classification into type I or type II synapse could not be unequivocally established, the morphological differentiation was considered as “undefined.” Such an association consisted of an axon terminal being in direct contact with the plasma membrane of a dendrite or soma with no intervening glial processes. Undefined associations do not imply that a synaptic specialization does not exist, but rather that, in the plane of section analyzed, the classification of the synapse was not possible unless identified in serial sections. In sections dually labeled for κ-OR and VGlut, at least four randomly selected sections with optimal preservation of ultrastructural morphology were examined per animal (n = 5). The criteria for defining an axon terminal as immunolabeled was by using detection of at least two to three silver grains in a cellular profile. From the surface of the individual Epon block containing the tissue section, at least 20 grids containing four to eight ultrathin sections were collected. Fields of at least 11,000× magnification showing random profiles containing immunogold-silver labeling for VGlut and peroxidase labeling for κ-OR at the plastic-Epon interface were tallied and evaluated for both labels in common axon terminals. This approach resulted in 195 κ-OR-labeled profiles. Similarly, sections dually labeled for κ-OR and CRF were analyzed following the same protocol. Briefly, κ-OR and CRF axons and axon terminals were tallied from fields of at least 11,000× magnification found in at least 20 grids containing four to eight ultrathin sections taken from four sections from each animal (n = 4). Fields showing immunogold-silver labeling for κ-OR and peroxidase labeling for CRF were tallied and evaluated for both labels in common axon terminals. This approach resulted in 261 κ-OR-labeled profiles.

Electrophysiological recordings in anesthetized rats.

Rats were anesthetized in 2% isoflurane-air mixture and prepared for recording LC neuronal activity from glass micropipettes as previously described (Curtis et al., 1997). For some studies, a catheter was inserted into the jugular vein for administration of sodium nitroprusside to produce hypotensive stress. Double-barrel micropipettes were used to record neuronal activity and simultaneously microinfuse agents. LC spontaneous activity was recorded for at least 3 min. In some experiments, this was followed by a trial of sciatic nerve stimulation (60 stimuli, 5.0 mA, 0.5 ms duration, 0.2 Hz) (Valentino and Foote, 1987). Agents were microinfused into the LC (30–60 nl) by applying small pulses of pressure (15–25 psi, 10–30 ms in duration) at a frequency of 0.2–1.0 Hz using a controlled source of pressure (Picospritzer; General Valve). LC activity was recorded for at least 3 min after the infusion and this was followed by either a trial of sciatic nerve stimulation or intravenous infusion of sodium nitroprusside. For hypotensive challenge, sodium nitroprusside (Sigma-Aldrich) was infused (0.66 mg in 1 ml; 40 μl/min) through the jugular catheter for at least 9 min.

Morphine was chronically administered as described previously (Valentino and Wehby, 1989). Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane and an osmotic minipump (Alzet catalog #2001) filled with 0.2 ml of sterile saline or morphine sulfate (50 mg/ml in sterile saline) was implanted subcutaneously. Tubing connected the outflow of the pump to a combination osmotic pump/guide cannula (which contained an additional cannula for acute i.c.v. injection during the experiment; C313G-330OP; Plastics One). This was implanted with the tip in the lateral ventricle for intracerebroventricular delivery (1 μl/hr). Rats were individually housed after surgery. Electrophysiology experiments were performed in the anesthetized state 7 d after implantation. For these studies, artificial CSF (ACSF) or the κ-OR agonist (trans)-3,4-dichloro-N-methyl-N-[2-1-pyrrolidinyl)-cyclo-hexyl] benzeneacetamide (U50488) was microinfused into the LC 3 min before intracerebroventricular injection of the selective μ-opiate receptor antagonist, d-Phe-Cys-Tyr-d-Trp-Arg-Thr-Pen-Thr-NH2 (CTAP). LC activity was recorded for an additional 9 min after the injection.

After each experiment, the recording site was marked by the iontophoresis of Pontamine sky blue from the recording electrode (−15 μA; 10–15 min). The brains were dissected out and 30 μm frozen sections were cut and stained with neutral red for localization of the recording site. Data were analyzed only from those neurons histologically identified as being within the nucleus LC.

Each determination represents a single cell in an individual animal. The effect of infusions on LC spontaneous discharge rate was determined by the Student's t test for matched-pair samples. LC activity during sciatic nerve stimulation trials were recorded as peristimulus time histograms (PSTHs) and analyzed as described previously (Valentino and Foote, 1987). Briefly, the histogram was divided into different time components and the discharge rate for each component was determined. The first 500 ms represented the unstimulated or tonic activity. The evoked component was defined as that period after the stimulus when LC discharge rate exceeds the mean tonic discharge rate plus 1 SD. Rates during the different components were compared for the same cells before and after agonist administration by the Student's t test for matched-pair samples. The effect of the three doses of U50488 on evoked rate and signal-to-noise ratio was analyzed using a two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with time and treatment as factors. For all statistical analysis, values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The effect of hypotensive challenge was determined by a repeated-measures one-way ANOVA with time as the factor. A two-way ANOVA with treatment and time as factors was used to compare the effect of hypotensive challenge between ACSF and U50488. Post hoc analyses were performed using Fisher's PLSD test. Additionally, for each experiment, the mean maximal activation produced by hypotensive challenge was determined and compared between treatment groups using a Student's t test for independent samples. The effect of CTAP was determined using one-way repeated-measures ANOVA with time as the factor. A two-way ANOVA with treatment and time as factors was used to compare the effect of CTAP on LC discharge rate between ACSF and U50488 pretreatment groups. Post hoc analyses were performed using Fisher's PLSD test. Additionally, the mean maximal activation observed after CTAP administration to ACSF- or U50488-pretreated rats was determined and compared using a Student's t test for independent samples.

Electrophysiological recordings in unanesthetized rats.

Rats were anesthetized with isofluorane, positioned in a stereotaxic instrument, and surgically prepared for implantation of a microwire bundle consisting of eight Teflon-insulated 50 μm stainless-steel wires (NB Labs) into the LC. The wires were attached, along with ground wires to a Microstar head stage and connected to a 16-channel data acquisition system (AlphaLab; Alpha Omega). Accurate placement was aided by recording neuronal activity during the implantation procedure. The head stage was affixed to the skull with dental cement and postoperative recovery was at least 3 d before recording. For the first 2 d after the postoperative period, rats were habituated to a recording cage in which they had free movement. During these sessions, cables were connected to the head stage for 1 h to assess detection of LC waveforms. The recording protocol consisted of a baseline period (15 min) including two segments of spontaneous activity (5 min each), one before and one after a segment of sensory evoked activity elicited by auditory stimulation (3 kHz tone, 50 ms, 80 db intensity, presented at 0.25 Hz, 50 presentations, total time 5 min). At the end of the baseline period, saline (1 ml/kg, i.p.) or the κ agonist U50488 (5.0 mg/kg, i.p.) was administered and this was immediately followed by another segment of spontaneous activity (5 min) and a final segment of sensory evoked activity (5 min). Each subject received both saline (day 1) and U50488 (day 2). At the end of the experiment, current was passed through the electrode (10 μA, 15 s) and rats were perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde containing 5% potassium ferrocyanide to form a Prussian blue reaction product for identification of the electrode site.

Putative LC multiunit activity was recorded as continuous analog waveforms by the Alpha Omega system linked to a host computer. Extracellular unit waveforms were amplified at a gain up to 25,000× with a bandwidth of 400 Hz to 2.0 kHz. Multiunit activity on all eight wires (channels) was monitored in real time simultaneously during experiments, but sorting of multiunit activity was done off-line only. The Wave Mark template matching algorithm in Spike2 was used to discriminate putative LC single-unit waveforms. A set of waveforms identified by the Wave Mark template is verified as events from a single unit by analyses of principal component clusters and associated autocorrelograms. For principal component clusters, Spike2 generates a cluster of dots representing waveform events from a putative single unit in three-dimensional space. An ellipsoid representing 1 SD (in three-dimensional space) from the cluster centrality is generated with the cluster of waveform events. The lack of overlap of any two ellipsoids was considered verification that the clusters were events from separate single units. An autocorrelogram of a set of waveform events in which no spikes occurred during a refractory period of 3 ms was considered verification that those events were from a single unit. For each channel with LC activity, two to five single units were usually discriminated.

Tonic and evoked activity were calculated from PSTHs as described above for studies in anesthetized rats. The effect of saline or U50488 injection was determined by a preinjection and postinjection comparison within subjects and the effect of U50488 versus saline was compared between subjects using a Student's t test for independent samples. Comparisons for which p < 0.05 were considered significant.

Drugs.

Dynorphin-A was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Desiccated aliquots were diluted in ACSF on the day of the experiment and administered locally as 1 ng in 30 nl. The synthetic κ-OR agonist U50488 (Sigma-Aldrich) was administered as 10, 30, or 100 ng in 30 nl ACSF. The synthetic κ-OR antagonist nor-binaltorphamine (nor-BNI; Sigma-Aldrich) was administered as 100 ng in 30 nl ACSF (based on pilot dose–response studies). CTAP (Tocris Bioscience) was administered at a dose of 3 μg in 3 μl intracerebroventricularly.

Results

Colocalization of κ-OR with VGlut and CRF in axon terminals in the LC

Axon terminals containing κ-OR were localized in the same field as VGlut1-labeled axon terminals and CRF-labeled axon terminals. A substantial portion of κ-OR-immunolabeled terminals colocalized either VGlut1 (Fig. 1A,B) or CRF (Fig. 1C,D). In sections that were double labeled to visualize κ-OR and VGlut, 44% of a total of 195 κ-OR-labeled axon terminals were colabeled for VGlut1. In these same sections, the double-labeled axon terminals represented 63% of a total of 137 VGlut-labeled axon terminals. Of these κ-OR-VGlut terminals, 53% formed identifiable synapses (41% asymmetric, 12% symmetric), 38% had undefined associations, and 9% were separated from dendrites in the plane of the section by astrocytes. In sections that were double labeled for κ-OR and CRF, 41% of a total of 261 κ-OR-labeled axon terminals colocalized CRF. In these same sections, the double-labeled axon terminals represented 50% of CRF terminals. Of the κ-OR-CRF terminals 48% formed identifiable synapses (37% asymmetric, 11% symmetric), 45% had undefined associations, and 7% were separated from dendrites in the plane of the section by astrocytes. This localization of κ-OR is consistent with presynaptic modulation of glutamatergic and CRF afferents to the LC.

Figure 1.

Electron photomicrographs showing coexistence of κ-OR and VGlut or CRF in axon terminals in the LC. A, Two axon terminals contain gold-silver labeling for VGlut and peroxidase labeling for κ-OR (κ-OR+VGlut-t). The dually labeled axon terminals form asymmetric synapses (arrows) with unlabeled dendrites. B, An axon terminal containing gold-silver labeling (arrowheads) for κ-OR and peroxidase labeling for VGlut (κ-OR+VGlut-t) forms an asymmetric synapse (arrows) with a dendrite. C, D, Axon terminals exhibiting gold-silver labeling (arrowheads) for κ-OR and immunoperoxidase labeling for CRF (κ-OR+CRF-t) form asymmetric synapses (arrows) with unlabeled dendrites. m, Mitochondria. Scale bars, 0.50 μm.

κ-OR activation inhibits glutamatergic inputs to the LC engaged by sciatic nerve stimulation

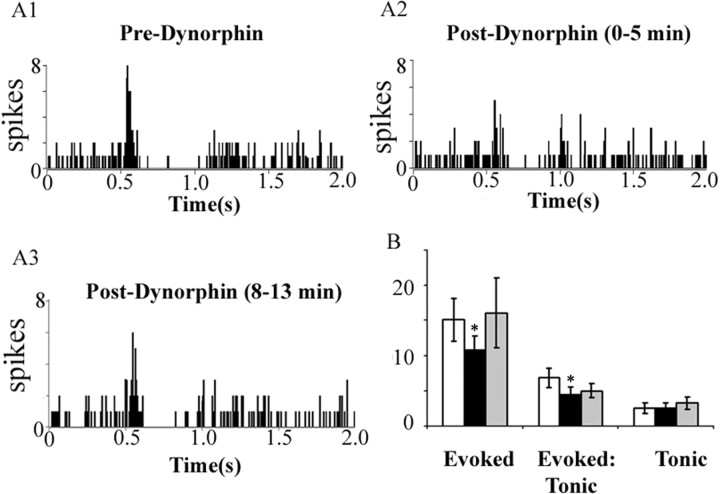

To assess the functional significance of the anatomic localization of κ-OR in the LC, the effects of κ-OR activation on LC spontaneous and sensory-evoked activity were quantified. Microinfusion of the endogenous κ-OR agonist dynorphin (1 ng in 30 nl) into the LC did not affect LC spontaneous activity. Mean LC discharge rates before and after dynorphin were 2.7 ± 0.7 Hz and 2.8 ± 0.8 Hz, respectively. During trials of sciatic nerve stimulation, dynorphin significantly decreased evoked but not tonic (unstimulated) discharge, resulting in a net decrease in the signal-to-noise ratio (Fig. 2). The effect of dynorphin was relatively transient, as the evoked response returned to preinjection values by the second stimulation trial 8 min later. Therefore, subsequent experiments used the nonpeptide κ-OR agonist U50488 to examine the impact of κ-OR activation in the LC.

Figure 2.

Dynorphin attenuates sensory-evoked LC discharge but does not alter tonic discharge. A1–A3, Representative PSTHs generated from trials of sciatic nerve stimulation before (Pre-Dynorphin), immediately after dynorphin (1 ng in 30 nl) microinfusion into the LC (Post-Dynorphin, 0–5 min), and 8 min after dynorphin infusion (Post-Dynorphin, 8–13 min). The abscissas indicate the time in seconds before and after stimulus, which occurred at 0.5 s. The ordinates indicate the cumulative number of discharges (spikes) in each 8 ms bin. B, Quantification of sensory-evoked discharge (Evoked), signal-to-noise ratio (Evoked:Tonic), and tonic discharge (Tonic). White, black, and gray bars represent determinations before and immediately after dynorphin administration, and 8 min after dynorphin administration, respectively. *p < 0.05, significantly different from predynorphin, Student's t test for matched pair samples (n = 4). Error bars indicate SEM.

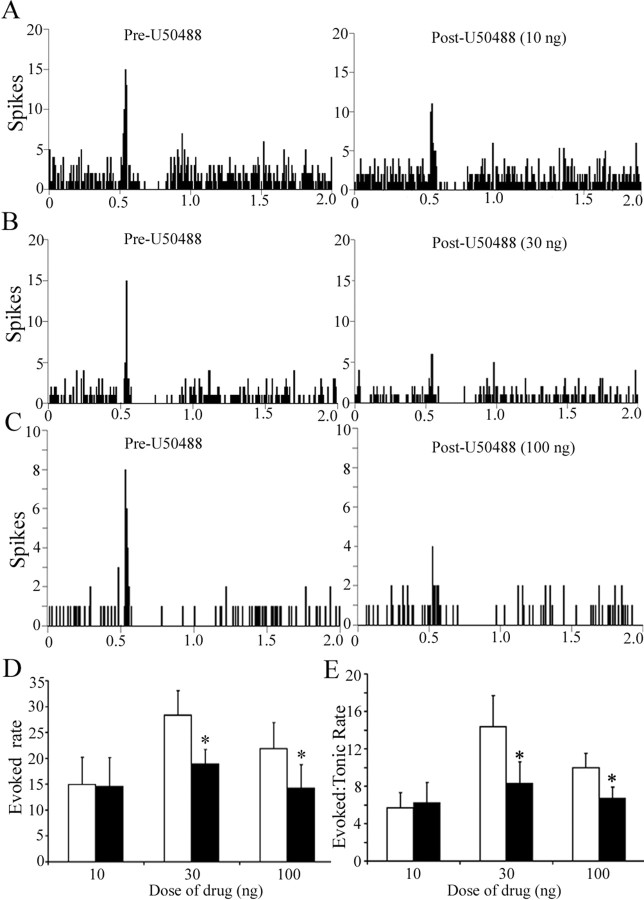

Figure 3 shows representative examples of the effect of different doses of U50488 on LC sensory-evoked responses and illustrates a selective decrease in evoked LC activity. Quantitative analyses confirmed that local microinfusion of U50488 into LC did not alter LC spontaneous discharge rate during the trials. In contrast, there was a dose-dependent decrease in evoked discharge and in the signal-to-noise ratio (Fig. 3D,E). Evoked activity recovered to baseline levels by 15 min after injection. Note that although the mean predrug evoked discharge rate appears variable between the different dose groups, these are not statistically different between groups.

Figure 3.

The synthetic κ-OR agonist U50488 attenuates LC sensory-evoked discharge in a dose-dependent manner. A–C, Representative PSTHs generated from trials of sciatic nerve stimulation before (Pre-U50488) and immediately after (Post-U50488) intra-LC microinfusion of U50488 at 10, 30, or 100 ng. The abscissas indicate the time in seconds before and after stimulus, which occurred at 0.5 s. The ordinates indicate the cumulative number of discharges (spikes) in each 8 ms bin. D, E, Quantification of sensory evoked discharge (Evoked rate) and of signal-to-noise ratio (Evoked:Tonic rate) before (white bar) and after (black bar) U50488. The abscissas indicate the dose (nanograms) and ordinates indicate the discharge rate (Hertz) in different components of the PSTH (D) or the ratio of evoked-to-tonic rate (E). The number of cells for 10, 30, and 100 ng was 9, 9, and 14, respectively. A two-way repeated-measures ANOVA for evoked rate revealed a significant main effect of treatment (F(1,29) = 21.36; p < 0.05) and interaction between treatment and dose (F(2,29) = 4.03; p < 0.05). Likewise, a two-way repeated-measures ANOVA for signal-to-noise revealed a significant main effect of treatment (F(1,29) = 7.22; p < 0.05). *p < 0.05, significantly different from pre-U50488. Error bars indicate SEM.

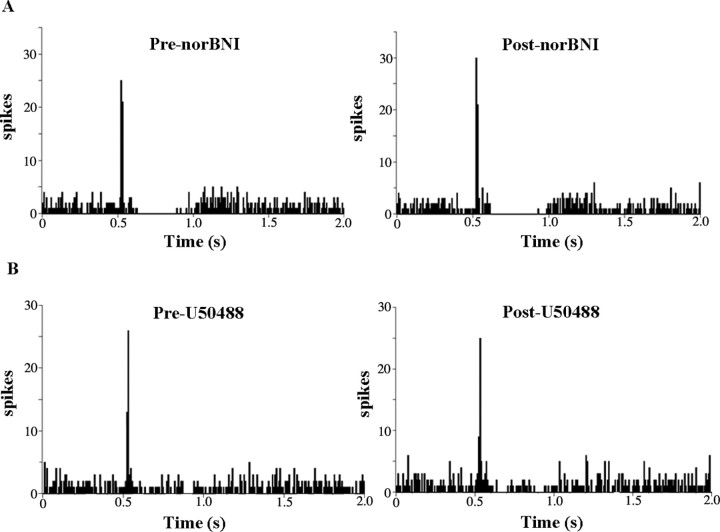

Microinfusion of the κ-OR antagonist nor-BNI (100 ng in 30 nl) into the LC did not alter spontaneous LC discharge rate, as the mean rates were 2.6 ± 0.4 Hz and 2.5 ± 0.5 Hz before and after nor-BNI, respectively (n = 10). Likewise, neither tonic nor evoked activity during trials of sciatic nerve stimulation were affected by nor-BNI (Fig. 4A). Mean tonic LC discharge was 2.7 ± 0.4 Hz and 2.6 ± 0.5 Hz before and after nor-BNI, respectively (n = 9). Mean evoked discharge rate was 16.7 ± 3.4 Hz and 18.4 ± 4.1 Hz before and after nor-BNI, respectively (n = 9). However, intra-LC microinfusion of nor-BNI prevented the inhibitory effects of U50488 on LC evoked activity (Fig. 4B). The mean evoked discharge rate before and after U50488 in subjects pretreated with nor-BNI was 16.4 ± 3.3 Hz and 18.6 + 6.9 Hz (n = 6).

Figure 4.

The κ-OR antagonist nor-BNI blocks the actions of U50488 in LC, but does not alter evoked or tonic discharge. A, Representative PSTHs generated from trials of sciatic nerve stimulation before (Pre-norBNI) and immediately after (Post-norBNI) microinfusion of nor-BNI (100 ng) into the LC. The abscissas indicate the time in seconds before and after stimulus, which occurred at 0.5 s. The ordinates indicate the cumulative number of discharges (spikes) in each 8 ms bin. B, Representative PSTHs generated from trials of sciatic nerve stimulation before (Pre-U50488) and immediately after (Post-U50488) LC microinfusion of U50488 (100 ng) after local pretreatment with nor-BNI.

κ-OR activation inhibits glutamatergic inputs to the LC engaged by morphine withdrawal

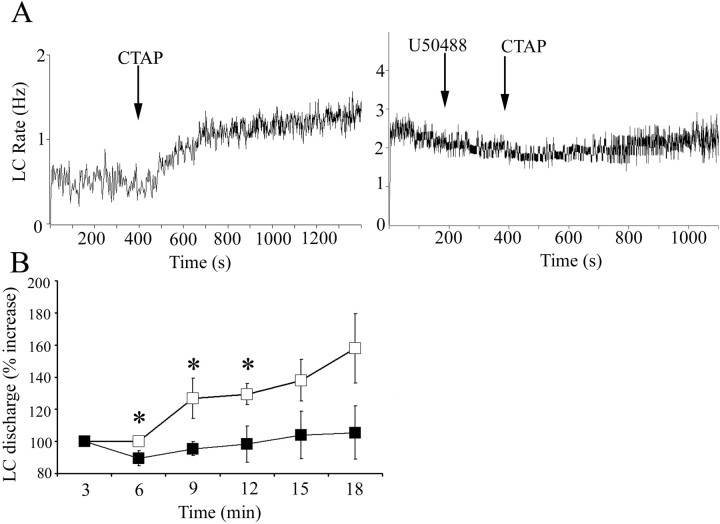

Precipitation of withdrawal by administration of naloxone to morphine-dependent animals activates LC neurons, in part via glutamatergic afferents from the nucleus paragigantocellularis (Rasmussen, 1995). Like naloxone, administration of the selective μ-opiate receptor antagonist CTAP to morphine-dependent rats increased LC discharge rate (Fig. 5A). Pretreatment with U50488, but not ACSF, attenuated CTAP-induced LC activation (Fig. 5A). A two-way ANOVA comparing groups treated with ACSF versus U50488 revealed an effect of treatment during the initial 9 min after CTAP infusion (F(1,29) = 10.3; p = 0.007) (Fig. 5B). Additionally, comparison of the maximum increase of LC discharge rate above baseline during 12 min after CTAP administration revealed a significant difference between rats pretreated with ACSF (185 ± 17% increase; n = 9) versus U50488 (107 ± 11% increase; n = 7; p < 0.05).

Figure 5.

The κ-OR agonist U50488 attenuates LC activation during opiate withdrawal. A, Representative traces showing LC spontaneous discharge rates after intracerebroventricular administration of CTAP (arrow) in morphine-dependent rats that were pretreated with ACSF (left) or U50488 (right) microinfusion into LC. The abscissas indicate the time in seconds. The ordinates indicate discharge rate (Hertz). Note that ACSF was administered before the start of the trace, but the original cell was lost and a second cell was recorded immediately after. B, Mean time course of LC discharge rate after CTAP administration after ACSF (open squares; n = 9) or U50488 (filled squares; n = 7). The abscissa indicates time in minutes after CTAP, whereas the ordinate indicates percentage increase in LC discharge. A one-way repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant effect of CTAP administration in ACSF-pretreated rats (F(3,35) = 4.35; p = 0.01), whereas there was no significant effect of CTAP administration after U50488 pretreatment (F(3,27) = 0.25; p > 0.05). A two-way repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of pretreatment (F(1,39) = 10.276; p = 0.007; *p < 0.05; statistically different from ACSF; Fisher's PLSD post hoc test). Error bars indicate SEM.

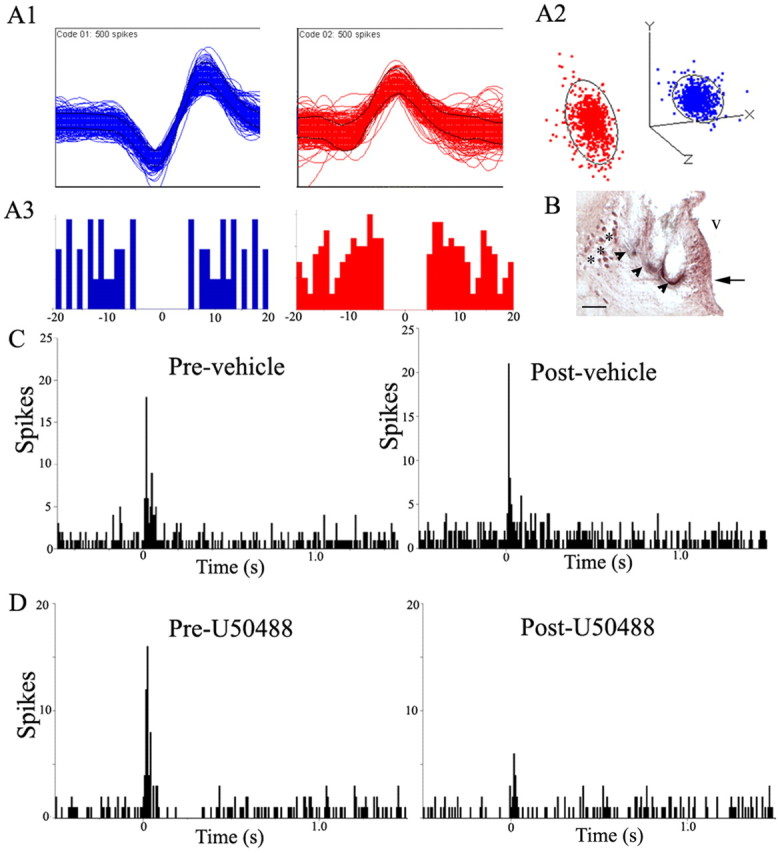

κ-OR activation inhibits auditory-evoked LC activation in unanesthetized rats

In unanesthetized rats, brief auditory stimuli evoke LC discharge and this response is attenuated by central administration of glutamate antagonists (Aston-Jones and Bloom, 1981a; Chiang et al., 1991). A total of 41 discriminated LC units were recorded from three subjects during trials of auditory stimulation. Figure 6A1 shows examples of the discriminated waveforms recorded simultaneously from the same wire. Autocorrelograms and the separation of clusters generated from principal component analysis provided evidence that these were individual units (Fig. 6A2,A3). Additionally, the observation that tonic activity before administration of either saline (1.8 ± 0.2 Hz; n = 12) or U50488 (2.0 ± 0.2 Hz; n = 29) was comparable with that determined for well discriminated LC units recorded with glass micropipettes in anesthetized rats was consistent with single-unit recordings in these unanesthetized subjects. Repeated auditory stimuli evoked LC discharge as shown in the representative PSTHs (Fig. 6C,D). Injection of either saline or U50488 produced a small, but statistically significant decrease in tonic activity. Thus, mean tonic activity before and after saline was 1.8 ± 0.2 Hz and 1.2 ± 0.3 Hz, respectively (p < 0.05), and before and after U50488 was 2.0 ± 0.2 Hz and 1.4 ± 0.2 Hz, respectively (p < 0.005). There was no difference in tonic discharge rate between the treatments. The magnitude of evoked activity was comparable before U50488 (18.1 ± 1.1 Hz) and saline (21.7 ± 2.3 Hz). Similar to its effects on LC activity evoked by sciatic nerve stimulation, U50488 attenuated the magnitude of auditory-evoked LC discharge (p < 0.0005, Student's t test for matched pairs), whereas saline was without effect. Moreover, the evoked rate determined after U50488 (11.4 ± 0.9 Hz) was significantly less than that determined after saline (18.0 ± 2.0 Hz) administration (p < 0.005, Student's t test for independent samples). Finally, the signal-to-noise ratio of the auditory response (evoked/tonic rate) was significantly less after U50488 (9.9 ± 0.9) compared with that determined after saline (22.6 ± 5.3; p < 0.05, Student's t test for independent samples). Data from one unit in the saline group that had an unusually high signal-to-noise ratio (254) because of a very low tonic rate (0.06 Hz) was omitted from this analysis. However, even with inclusion of this point in the analysis, the signal-to-noise ratios were significantly different between groups (9.9 ± 0.9 vs 41.9 ± 20.7 for U50488 vs saline, respectively; p < 0.05, Student's t test for independent samples).

Figure 6.

The κ-OR agonist U50488 attenuates LC activation by auditory stimuli in the awake, freely moving rat. A1, Representative multiunit waveforms from different putative LC neurons extracted from a multiunit analog record by template-matching software. A2, Cluster plot of the principal component analysis for representative waveforms. Each waveform in the template is represented by a color-coded event dot in the principal component space, thereby generating its respective PC cluster. The ellipsoids around the clusters are three-dimensional representations of 1 SD from cluster centrality. The lack of overlap of the ellipsoids suggests that the clusters represent single units. A3, Below each waveform is the color-coded autocorrelogram generated by interspike intervals between events. The abscissas indicate time in milliseconds, whereas the ordinates indicate number of intervals per bin. For LC neurons, onset of relative refractory period is 3 ms, suggesting that at least 2 ms to the left of 0 and 2 ms to the right of 0 should be devoid of spike interval histograms in an autocorrelogram of a single LC unit. B, Photomicrograph showing a coronal section stained with neutral red at the level of the LC. The arrowheads indicate the location of the multiunit electrodes. The arrow points to the LC. The asterisks indicate the mesencephalic trigeminal nucleus. V, Ventricle. Scale bar, 100 μm. C, Representative PSTHs generated from trials of auditory stimulus presentations before (Pre-vehicle) and immediately after (Post-vehicle) saline administration (1 ml/kg, i.p.). The abscissas indicate time in seconds before and after an auditory stimulus, which starts at 0 s, and the ordinates indicate cumulative number of discharges (spikes) in each 8 ms bin. D, Representative PSTHs generated from a trial of auditory stimulus presentations before (Pre-U50488) and immediately after (Post-U50488) κ-OR agonist administration (5 mg/kg, i.p.). The abscissas indicate time in seconds before and after the auditory stimulus, which starts at 0 s, and the ordinates indicate cumulative number of discharges (spikes) in each 8 ms bin.

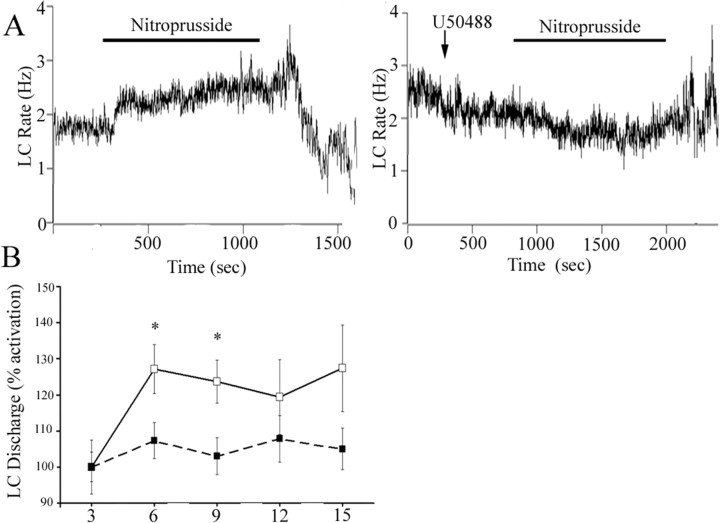

κ-OR activation inhibits CRF inputs to the LC engaged by hypotensive challenge

Unlike its activation by sciatic nerve stimulation or opiate withdrawal, LC activation by hypotensive challenge is completely mediated by CRF release in the LC (Valentino et al., 1991; Curtis et al., 2001). To determine whether κ-OR could modulate this major afferent to LC, the effects of U50488 on LC activation elicited by hypotensive stress were examined. Administration of nitroprusside after ACSF microinfusion increased LC discharge rate and in recordings that remained stable throughout the infusion, LC discharge decreased with termination of the infusion, as reported previously (Fig. 7) (Curtis et al., 2001). In contrast, pretreatment with U50488 (100 ng) prevented LC activation by hypotensive challenge (Fig. 7A,B). Additionally, comparison of the maximum increase of LC discharge rate above baseline during hypotensive challenge revealed a significant difference between rats pretreated with ACSF (38 ± 8% increase; n = 8) versus U50488 (13 ± 6% increase; n = 9; p < 0.02). Finally, there was a tendency for poststress inhibition to be attenuated in rats administered U50488 (Fig. 7A). However, this effect was not statistically significant and it was difficult to maintain cellular stability for the required period of time in a sufficient number of subjects to achieve the necessary power for this comparison.

Figure 7.

The κ-OR agonist U50488 attenuates LC activation by hypotensive stress. A, Representative traces showing LC spontaneous discharge rates during sodium nitroprusside infusion (bar) in rats pretreated with ACSF or U50488 (100 ng). The abscissa indicates the time in seconds. The ordinate indicates the discharge rate (Hertz). B, Mean time course of LC spontaneous discharge rates during sodium nitroprusside administration in rats pretreated with ACSF (open squares; n = 8) or U50488 (closed squares; n = 9). The abscissa indicates time in minutes, whereas the ordinate indicates percentage increase in LC discharge. A one-way repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant effect of sodium nitroprusside administration (F(3,27) = 9.738; p < 0.0005), whereas there was no significant effect after U50488 pretreatment (F(3,35) = 1.544; p > 0.05). A two-way repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a main effect of pretreatment (F(1,42) = 5.87; p = 0.03). *p < 0.05, statistically significant from ACSF, Fisher's PLSD post hoc analysis). Error bars indicate SEM.

Discussion

Through widespread forebrain projections, the LC–norepinephrine system regulates states of arousal and facilitates decisions on behavioral strategies in dynamic environmental situations (Berridge and Waterhouse, 2003; Aston-Jones and Cohen, 2005). Information about the internal and external environment is relayed through afferents that converge in the LC and affect neuronal activity. Therefore, modulation of LC afferents can be a powerful means of influencing cognitive and behavioral responses to diverse stimuli. This study provided evidence for κ-OR modulation of diverse LC afferents. κ-OR was prominently colocalized with VGlut and with CRF in axon terminals in the LC. Electrophysiological studies were consistent with presynaptic effects, as κ-OR agonists did not alter spontaneous LC activity. Rather, activation of κ-OR in the LC had the unique consequence of consistently attenuating neuronal discharge evoked by engaging either excitatory amino acid or CRF inputs. Through the ability to inhibit neurochemically distinct afferents that are engaged by diverse stimuli, κ-ORs can exert a powerful influence over the LC–NE system. This represents a new dimension of regulation of LC activity that may be targeted to treat multiple psychiatric disorders.

Technical considerations

The interpretation of κ-OR labeling in axon terminals is based on specific structural features (Peters et al., 1991). Although many of these formed synapses in the plane of the section, the ultrathin sectioning made it impossible to determine whether all labeled terminals formed synapses. This would require serial reconstruction, which was out of the scope of this study.

The electrophysiological effects observed were considered to be κ-OR-mediated based on high pharmacological selectivity of the agents used (Stevens et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2005). It is noteworthy that κ-OR-mediated effects on LC sensory responses are opposite to those produced by μ-opiate receptor activation and unlike effects produced by δ-opiate receptor activation, arguing against an involvement of those receptors (North et al., 1987; Valentino and Wehby, 1988; Pan et al., 2002).

Presynaptic actions of κ opiate receptors in brain

Presynaptic effects of κ-OR activation in the LC are reminiscent of its function in other brain regions. κ-ORs are localized in axon terminals in the rostral ventromedial medulla (Drake et al., 2007), nucleus accumbens shell (Svingos et al., 1999), and medial prefrontal cortex (Svingos and Colago, 2002). κ-OR-mediated presynaptic inhibition has been reported in hippocampus (Weisskopf et al., 1993; Simmons and Chavkin, 1996), globus pallidus (Ogura and Kita, 2000), rostral ventral medulla (Ackley et al., 2001), nucleus ambiguus (Wang et al., 2004), nucleus raphe magnus (Bie and Pan, 2003), and nucleus accumbens shell (Hjelmstad and Fields, 2001). In these regions, glutamate, glycine, and GABA neurotransmission were targets of κ-OR-mediated presynaptic effects. Thus, κ-ORs can have a broad impact through presynaptic modulation of diverse neurotransmitters.

Implications of presynaptic regulation of EAA afferents to LC

LC neurons are spontaneously active and discharge in both tonic and phasic modes (Foote et al., 1980; Aston-Jones and Bloom, 1981a,b). Phasic LC activation by discrete multimodal sensory stimuli is thought to direct attention toward the stimuli and facilitate behavioral outcomes associated with the stimuli (Berridge and Waterhouse, 2003; Aston-Jones and Cohen, 2005). The brief synchronous burst of LC discharge elicited by sensory stimuli is consistent with EAA drive and the well described activation of LC neurons by sciatic nerve stimulation is mediated by medullary EAA inputs (Ennis et al., 1992). A selective decrease in the magnitude of LC phasic sensory responses by κ-OR activation should translate to attenuated reactions to sensory stimuli and decreased ability of these stimuli to direct or alter the course of ongoing behavior. The lack of effect on tonic activity implies that this would occur in the absence of alterations in arousal. Consistent with reducing the impact of sensory stimuli, κ-OR agonists disrupt performance in an attention task, the five-choice serial reaction-time task, by increasing number of omissions and latency to respond (Paine et al., 2007; Shannon et al., 2007). These effects could also be expressed as a blunting of affect that characterizes depression. In this regard, previous studies have implicated the dynorphin–κ-OR system in depression and suggest that κ-OR antagonists may be useful antidepressants (Pliakas et al., 2001; Mague et al., 2003; McLaughlin et al., 2003, 2006b; Shirayama et al., 2004). Although these studies focused on κ-OR actions in forebrain, findings of increased κ-OR gene expression in the LC of the Wistar-Kyoto rat (a strain that exhibits a depressive phenotype) support a role for κ-OR in the LC in depression (Pearson et al., 2006). In other clinical conditions that are characterized by excessive responses to sensory stimuli, the ability of κ-OR agonists to blunt these responses without altering the state of arousal might be therapeutically useful. Examples include attentional disorders, where sensory stimuli are significant distracters, or autism, which can present as unusually heightened sensory responses (Gomot et al., 2002; Tomchek and Dunn, 2007). Interestingly, antagonizing κ-OR in the LC did not alter sensory evoked responses, implying a lack of endogenous κ-OR tone in LC. This may occur only in certain conditions such as chronic stress, which upregulates prodynorphin mRNA in the central nucleus of the amygdala, an afferent to the LC (Chen et al., 2004; Shirayama et al., 2004).

LC neuronal excitation produced by antagonist-precipitated opiate withdrawal has been implicated in certain aspects of the withdrawal syndrome (Redmond and Huang, 1982; Rasmussen et al., 1990; Maldonado et al., 1992; Han et al., 2006). EAA afferents mediate a component of this neural correlate of opiate withdrawal. Thus, intra-LC infusion of EAA antagonists LC reduces, but does not abolish, this response (Rasmussen and Aghajanian, 1989; Akaoka and Aston-Jones, 1991; Rasmussen et al., 1991). The present demonstration that κ-OR activation in the LC also attenuates the excitation of LC neurons by opiate withdrawal is consistent with presynaptic inhibition of glutamate afferents that mediate the effect and suggests that κ-OR agonists might be useful in alleviating symptoms of opiate withdrawal.

Implications of presynaptic regulation of CRF afferents to LC

U50488 decreased LC activation by a stimulus that engages CRF afferents, underscoring the general nature of κ-OR presynaptic inhibition in the LC. CRF is thought to serve as a neuromodulator in the LC that increases its activity in response to many stressors (Lehnert et al., 1998; Koob, 1999; Valentino and Van Bockstaele, 2005). CRF is also released to impact on LC neurons during swim stress as demonstrated by receptor internalization (Reyes et al., 2008) and handling stress, as demonstrated by norepinephrine efflux (Kawahara et al., 2000). Attenuation of stress-induced LC activation might seem counter to recent studies linking the dynorphin–κ-OR system with stress-related pathology such as depression (see above). However, this may be explained by considering that acute stress-elicited LC activation by CRF is adaptive (see below). By blunting that response, κ-OR agonists may set up conditions that favor maladaptive responses. For example, CRF activation of the LC is associated with increased activity in the swim test (Butler et al., 1990; Xu et al., 2004), whereas κ-OR agonists are associated with immobility, which is generally considered to be a depression-like response.

Relevance of κ-OR-mediated presynaptic inhibition for LC function

A salient attribute of the LC is its ability to change discharge rate and pattern in tune with dynamic environments. Aston-Jones and Cohen (2005) propose a model whereby tonic and phasic modes of LC discharge facilitate distinct processes. In this model, phasic activity facilitates ongoing behavior and optimizes performance in tasks requiring selective attention, whereas tonic activity promotes attention to irrelevant stimuli, disengagement from ongoing tasks and searching for alternate tasks when present behavior is not optimal. By biasing LC activity toward a particular discharge mode, EAA, opioid, and CRF afferents can shape predominant behavioral strategies in these environments. EAA afferents would facilitate selective attention and optimal performance of ongoing tasks through enhancement of phasic discharge. CRF shifts LC activity toward a high tonic and lower phasic mode, an effect associated with hyperarousal, disengagement from ongoing behavior, and scanning of environmental stimuli (Valentino and Foote, 1987, 1988). In contrast, endogenous opioids acting at μ-OR receptors bias activity toward the phasic mode, by selectively decreasing tonic activity (Valentino and Wehby, 1988). In opposition to CRF, engaging μ-OR should promote focused attention and maintenance of ongoing behavior. Consequences of κ-OR presynaptic inhibition contrast all of these. By decreasing the ability of stimuli to phasically activate LC neurons, ongoing behavior and performance in tasks requiring focused attention will be disrupted (as is seen in five-choice serial reaction task). At the same time, by decreasing tonic activation, the impetus to seek alternate strategies will not be promoted. Because spontaneous activity is unaffected, this unresponsive state should be present in the absence of sedation. The passive and indecisive nature of the WKY rat, which has increased κ-OR gene expression in the LC, is compatible with this model (Pare, 1992a,b, 1993). In summary, κ-OR-mediated presynaptic inhibition of LC afferents represents a novel level of regulation that takes the LC “off-line” and this may be important in its link to depression.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (DA09082 and DA16898), National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke (T32NS007413), and the Office of Naval Research (ONR N0014-03-1-0311). We thank Ms. Lisa Shulke for technical assistance with histology.

References

- Abercrombie ED, Jacobs BL. Single unit response of noradrenergic neurons in locus ceruleus of freely moving cats. I. Acutely presented stressful and nonstressful stimuli. J Neurosci. 1987;7:2837–2843. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-09-02837.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackley MA, Hurley RW, Virnich DE, Hammond DL. A cellular mechanism for the antinociceptive effect of a kappa opioid receptor agonist. Pain. 2001;91:377–388. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00464-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akaoka H, Aston-Jones G. Opiate withdrawal-induced hyperactivity of locus coeruleus neurons is substantially mediated by augmented excitatory amino acid input. J Neurosci. 1991;11:3830–3839. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-12-03830.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Bloom FE. Norepinephrine-containing locus coeruleus neurons in behaving rats exhibit pronounced responses to non-noxious environmental stimuli. J Neurosci. 1981a;1:887–900. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-08-00887.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Bloom FE. Activity of norepinephrine-containing locus coeruleus neurons in behaving rats anticipates fluctuations in the sleep-waking cycle. J Neurosci. 1981b;1:876–886. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-08-00876.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Cohen JD. An integrative theory of locus coeruleus-norepinephrine function: adaptive gain and optimal performance. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2005;28:403–450. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Shipley MT, Chouvet G, Ennis M, Van Bockstaele EJ, Pieribone V, Shiekhattar R, Akaoka H, Drolet G, Astier B, Charlety P, Valentino R, Williams JT. Afferent regulation of locus coeruleus neurons: anatomy, physiology and pharmacology. Prog Brain Res. 1991;85:47–75. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)63799-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge CW, Waterhouse BD. The locus coeruleus-noradrenergic system: modulation of behavioral state and state-dependent cognitive processes. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2003;42:33–84. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(03)00143-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bie B, Pan ZZ. Presynaptic mechanism for anti-analgesic and anti-hyperalgesic actions of kappa-opioid receptors. J Neurosci. 2003;23:7262–7268. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-19-07262.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler PD, Weiss JM, Stout JC, Nemeroff CB. Corticotropin-releasing factor produces fear-enhancing and behavioral activating effects following infusion into the LC. J Neurosci. 1990;10:176–183. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-01-00176.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JX, Li W, Zhao X, Yang JX, Xu HY, Wang ZF, Yue GX. Changes of mRNA expression of enkephalin and prodynorphin in hippocampus of rats with chronic immobilization stress. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:2547–2549. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i17.2547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang C, Curtis AL, Drolet G, Valentino RJ, Aston-Jones G. Auditory responses of locus coeruleus neurons are attenuated by excitatory amino acid receptor antagonists in the awake rat. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1991;17:1540. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis AL, Florin-Lechner SM, Pavcovich LA, Valentino RJ. Activation of the locus coeruleus noradrenergic system by intracoerulear microinfusion of corticotropin-releasing factor: effects on discharge rate, cortical norepinephrine levels and cortical electroencephalographic activity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;281:163–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis AL, Bello NT, Valentino RJ. Endogenous opioids in the locus coeruleus function to limit the noradrenergic response to stress. J Neurosci. 2001;21(RC152) doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-13-j0001.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePaoli AM, Hurley KM, Yasada K, Reisine T, Bell G. Distribution of kappa opioid receptor mRNA in adult mouse brain: an in situ hybridization histochemistry study. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1994;5:327–335. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1994.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake CT, De Oliveira AX, Harris JA, Connor DM, Winkler CW, Aicher SA. Kappa opioid receptors in the rostral ventromedial medulla of male and female rats. J Comp Neurol. 2007;500:465–476. doi: 10.1002/cne.21184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennis M, Aston-Jones G, Shiekhattar R. Activation of locus coeruleus neurons by nucleus paragigantocellularis or noxious sensory stimulation is mediated by intracoerulear excitatory amino acid neurotransmission. Brain Res. 1992;598:185–195. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90182-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foote SL, Aston-Jones G, Bloom FE. Impulse activity of locus coeruleus neurons in awake rats and monkeys is a function of sensory stimulation and arousal. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:3033–3037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.5.3033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomot M, Giard MH, Adrien JL, Barthelemy C, Bruneau N. Hypersensitivity to acoustic change in children with autism: electrophysiological evidence of left frontal cortex dysfunctioning. Psychophysiology. 2002;39:577–584. doi: 10.1017.S0048577202394058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray EG. Axosomatic and axo-dendritic synapses of the cerebral cortex: an electron microscopic study. J Anat. 1959;93:420–433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han MH, Bolanos CA, Green TA, Olson VG, Neve RL, Liu RJ, Aghajanian GK, Nestler EJ. Role of cAMP response element-binding protein in the rat locus ceruleus: regulation of neuronal activity and opiate withdrawal behaviors. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4624–4629. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4701-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjelmstad GO, Fields HL. Kappa opioid receptor inhibition of glutamatergic transmission in the nucleus accumbens shell. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:1153–1158. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.3.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahara H, Kawahara Y, Westerink BH. The role of afferents to the locus coeruleus in the handling stress-induced increase in the release of norepinephrine in the medial prefrontal cortex: a dual-probe microdialysis study in the rat brain. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;387:279–286. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00793-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF. Corticotropin-releasing factor, norepinephrine, and stress. Biol Psych. 1999;46:1167–1180. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00164-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehnert H, Schulz C, Dieterich K. Physiological and neurochemical aspects of corticotropin-releasing factor actions in the brain: the role of the locus coeruleus. Neurochem Res. 1998;23:1039–1052. doi: 10.1023/a:1020751817723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mague SD, Pliakas AM, Todtenkopf MS, Tomasiewicz HC, Zhang Y, Stevens WC, Jr, Jones RM, Portoghese PS, Carlezon WA., Jr Antidepressant-like effects of kappa-opioid receptor antagonists in the forced swim test in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;305:323–330. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.046433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado R, Stinus L, Gold LH, Koob GF. Role of different brain structures in the expression of the physical morphine withdrawal syndrome. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;261:669–677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour A, Fox CA, Meng F, Akil H, Watson SJ. Kappa 1 receptor mRNA distribution in the rat CNS: comparison to kappa receptor binding and prodynorphin mRNA. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1994;5:124–144. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1994.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin JP, Marton-Popovici M, Chavkin C. Kappa opioid receptor antagonism and prodynorphin gene disruption block stress-induced behavioral responses. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5674–5683. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-13-05674.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin JP, Li S, Valdez J, Chavkin TA, Chavkin C. Social defeat stress-induced behavioral responses are mediated by the endogenous kappa opioid system. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006a;31:1241–1248. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin JP, Land BB, Li S, Pintar JE, Chavkin C. Prior activation of kappa opioid receptors by U50,488 mimics repeated forced swim stress to potentiate cocaine place preference conditioning. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006b;31:787–794. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morilak DA, Fornal C, Jacobs BL. Effects of physiological manipulations on locus coeruleus neuronal activity in freely moving cats. II. Cardiovascular challenge. Brain Res. 1987;422:24–31. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90536-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North RA, Williams JT, Surprenant A, Christie MJ. Mu and delta receptors belong to a family of receptors that are coupled to potassium channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:5487–5491. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.15.5487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura M, Kita H. Dynorphin exerts both postsynaptic and presynaptic effects in the Globus pallidus of the rat. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:3366–3376. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.6.3366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page ME, Akaoka H, Aston-Jones G, Valentino RJ. Bladder distention activates locus coeruleus neurons by an excitatory amino acid mechanism. Neuroscience. 1992;51:555–563. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90295-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page ME, Berridge CW, Foote SL, Valentino RJ. Corticotropin-releasing factor in the locus coeruleus mediates EEG activation associated with hypotensive stress. Neurosci Lett. 1993;164:81–84. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90862-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paine TA, Tomasiewicz HC, Zhang K, Carlezon WA., Jr Sensitivity of the five-choice serial reaction time task to the effects of various psychotropic drugs in Sprague-Dawley rats. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:687–693. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan YZ, Li DP, Chen SR, Pan HL. Activation of delta opioid receptors excites spinally projecting locus coeruleus neurons through inhibition of GABAergic inputs. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:2675–2683. doi: 10.1152/jn.00298.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pare WP. Learning behavior, escape behavior and depression in an ulcer susceptible rat strain. Integrat Physiol Behav Sci. 1992a;27:130–141. doi: 10.1007/BF02698502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pare WP. The performance of WKY rats on three tests of emotional behavior. Physiol Behav. 1992b;51:1051–1056. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(92)90091-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pare WP. Passive-avoidance behavior in Wistar-Kyoto (WKY), Wistar, and Fischer-344 rats. Physiol Behav. 1993;54:845–852. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(93)90291-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson KA, Stephen A, Beck SG, Valentino RJ. Identifying genes in monoamine nuclei that may determine stress vulnerability and depressive behavior in Wistar-Kyoto rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2449–2461. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Palay SL, Webster HD. New York: Oxford UP; 1991. The fine structure of the nervous system. [Google Scholar]

- Pliakas AM, Carlson RR, Neve RL, Konradi C, Nestler EJ, Carlezon WA., Jr Altered responsiveness to cocaine and increased immobility in the forced swim test associated with elevated cAMP response element-binding protein expression in nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7397–7403. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-18-07397.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen K. The role of the locus coeruleus and N-methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA) and AMPA receptors in opiate withdrawal. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1995;13:295–300. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(95)00082-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen K, Aghajanian GK. Withdrawal-induced activation of locus coeruleus neurons in opiate-dependent rats: attenuation by lesions of the nucleus paragigantocellularis. Brain Res. 1989;505:346–350. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91466-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen K, Beitner-Johnson DB, Krystal JG, Aghajanian GK, Nestler EJ. Opiate withdrawal and rat locus coeruleus: behavioral, electophysiological and biochemical correlates. J Neurosci. 1990;10:2308–2317. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-07-02308.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen K, Krystal JH, Aghajanian GK. Excitatory amino acids and morphine withdrawal: differential effects of central and peripheral kynurenic acid administration. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1991;105:508–512. doi: 10.1007/BF02244371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redmond ED, Jr, Huang YH. The primate locus coeruleus and effects of clonidine on opiate withdrawal. J Clin Psychol. 1982;43:25–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes BA, Fox K, Valentino RJ, Van Bockstaele EJ. Agonist-induced internalization of corticotropin-releasing factor receptors in noradrenergic neurons of the rat locus coeruleus. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:2991–2998. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes BA, Johnson AD, Glaser JD, Commons KG, Van Bockstaele EJ. Dynorphin-containing axons directly innervate noradrenergic neurons in the rat nucleus locus coeruleus. Neuroscience. 2007;145:1077–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.12.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes BA, Valentino RJ, Van Bockstaele EJ. Stress-induced intracellular trafficking of corticotropin-releasing factor receptors in rat locus coeruleus neurons. Endocrinology. 2008;149:122–130. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon HE, Eberle EL, Mitch CH, McKinzie DL, Statnick MA. Effects of kappa opioid receptor agonists on attention as assessed by a 5-choice serial reaction time task in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2007;53:930–941. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirayama Y, Ishida H, Iwata M, Hazama GI, Kawahara R, Duman RS. Stress increases dynorphin immunoreactivity in limbic brain regions and dynorphin antagonism produces antidepressant-like effects. J Neurochem. 2004;90:1258–1268. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons ML, Chavkin C. k-Opioid receptor activation of a dendrotoxin-sensitive potassium channel mediates presynaptic inhibition of mossy fiber neurotransmitter release. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;50:80–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens WC, Jr, Jones RM, Subramanian G, Metzger TG, Ferguson DM, Portoghese PS. Potent and selective indolomorphinan antagonists of the kappa-opioid receptor. J Med Chem. 2000;43:2759–2769. doi: 10.1021/jm0000665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson TH. Peripheral, autonomic regulation of locus coeruleus noradrenergic neurons in brain: Putative implications for psychiatry and psychopharmacology. Psychopharmacology. 1987;92:1–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00215471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svingos AL, Colago EE. Kappa-opioid and NMDA glutamate receptors are differentially targeted within rat medial prefrontal cortex. Brain Res. 2002;946:262–271. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02894-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svingos AL, Colago EE, Pickel VM. Cellular sites for dynorphin activation of kappa-opioid receptors in the rat nucleus accumbens shell. J Neurosci. 1999;19:1804–1813. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-05-01804.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson LW. The locus coeruleus: a cytoarchitectonic, Golgi and immunohistochemical study in the albino rat. Brain Res. 1976;110:39–56. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90207-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson LW, Hartman BK. The central adrenergic system. An immunofluorescence study of the location of cell bodies and their efferent connections in the rat using dopamine-β-hydroxylase as a marker. J Comp Neurol. 1976;163:467–506. doi: 10.1002/cne.901630406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomchek SD, Dunn W. Sensory processing in children with and without autism: a comparative study using the short sensory profile. Am J Occup Ther. 2007;61:190–200. doi: 10.5014/ajot.61.2.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vale W, Spiess J, Rivier C, Rivier J. Characterization of a 41-residue ovine hypothalamic peptide that stimulates secretion of corticotropin and beta-endorphin. Science. 1981;213:1394–1397. doi: 10.1126/science.6267699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Foote SL. Corticotropin-releasing factor disrupts sensory responses of brain noradrenergic neurons. Neuroendocrinology. 1987;45:28–36. doi: 10.1159/000124700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Foote SL. Corticotropin-releasing factor increases tonic but not sensory-evoked activity of noradrenergic locus coeruleus neurons in unanesthetized rats. J Neurosci. 1988;8:1016–1025. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-03-01016.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Van Bockstaele EJ. Opposing regulation of the locus coeruleus by corticotropin-releasing factor and opioids: potential for reciprocal interactions between stress and opioid sensitivity. Psychopharmacology. 2001;158:331–342. doi: 10.1007/s002130000673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Van Bockstaele EJ. Functional interactions between stress neuromediators and the locus coeruleus-noradrenaline system. In: Steckler T, Kalin N, Reul JMHM, editors. Handbook of stress and the brain. Vol. 16. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2005. pp. 465–486. [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Wehby RG. Morphine effects on locus coeruleus neurons are dependent on the state of arousal and availability of external stimuli: studies in anesthetized and unanesthetized rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1988;244:1178–1186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Wehby RG. Locus coeruleus discharge characteristics of morphine-dependent rats: effects of naltrexone. Brain Res. 1989;488:126–134. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90701-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Page ME, Curtis AL. Activation of noradrenergic locus coeruleus neurons by hemodynamic stress is due to local release of corticotropin-releasing factor. Brain Res. 1991;555:25–34. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90855-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele EJ, Bajic D, Proudfit H, Valentino RJ. Topographic architecture of stress-related pathways targeting the noradrenergic locus coeruleus. Physiol Behav. 2001;73:273–283. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(01)00448-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Dergacheva O, Griffioen KJ, Huang ZG, Evans C, Gold A, Bouairi E, Mendelowitz D. Action of kappa and Delta opioid agonists on premotor cardiac vagal neurons in the nucleus ambiguus. Neuroscience. 2004;129:235–241. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Tang K, Inan S, Siebert D, Holzgrabe U, Lee DYW, Huang P, Li JG, Cowan A, Liu-Chen LY. Comparison of pharmacological activities of three distinct κ ligands (salvinorin A, TRK-820 and 3FLB) on κ opioid receptors in vitro and their antipruritic and antinociceptive activities in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;312:220–230. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.073668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisskopf MG, Zalutsky RA, Nicoll RA. The opioid peptide dynorphin mediates heterosynaptic depression of hippocampal mossy fibre synapses and modulates long-term potentiation. Nature. 1993;362:423–427. doi: 10.1038/362423a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G, Van Bockstaele EJ, Reyes B, Bethea T, Valentino RJ. Chronic morphine sensitizes the brain norepinephrine system to corticotropin-releasing factor and stress. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8193–8197. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1657-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]