Abstract

Female sex hormones influence the neural control of breathing and may impact neurologic recovery from spinal cord injury. We hypothesized that respiratory recovery after C2 spinal hemisection (C2HS) differs between males and females and is blunted by prior ovariectomy (OVX) in females. Inspiratory tidal volume (VT), frequency (fR), and ventilation (VE) were quantified during quiet breathing (baseline) and 7% CO2 challenge before and after C2HS in unanesthetized adult rats via plethysmography. Baseline breathing was similarly altered in all rats (reduced VT, elevated fR) but during hypercapnia females had relatively higher VT (i.e. compared to pre-injury) than male or OVX rats (p < 0.05). Phrenic neurograms recorded in anesthetized rats indicated that normalized burst amplitude recorded ipsilateral to C2HS (i.e. the crossed phrenic phenomenon) is greater in females during respiratory challenge (p < 0.05 vs. male and OVX). We conclude that sex differences in recovery of VT and phrenic output are present at 2 weeks post-C2HS. These differences are consistent with the hypothesis that ovarian sex hormones influence respiratory recovery after cervical spinal cord injury.

Keywords: Plasticity, Spinal cord injury, Sex, Ovariectomy, Phrenic, Gender

1. Introduction

Respiratory control differences between males and females suggest that endogenous steroid sex hormones influence the behavior of respiratory neurons and/or networks (reviewed in Dempsey et al., 1986; Behan et al., 2003). Sex hormones also influence plasticity in respiratory control, and in particular the expression of respiratory long-term facilitation (LTF) following episodes of hypoxia (Behan et al., 2002; Zabka et al., 2001, 2005, 2006). Further, several examples of developmental plasticity in respiratory control are unique to either males or females (Joseph et al., 2000; Bavis and Kilgore, 2001; Bavis et al., 2004; Montandon et al., 2006). Sex hormones also appear to influence histological and functional outcomes after injuries to the central nervous system. For example, several studies have reported improved outcomes in female vs. male rodents following brain or spinal cord injury (SCI) (Alkayed et al., 1998; Bramlett and Dietrich, 2001; Farooque et al., 2006; Hauben et al., 2002).

A well-documented example of intrinsic repair and plasticity following SCI is the “crossed phrenic phenomenon” (CPP, reviewed in Goshgarian, 2003; Zimmer et al., 2007, 2008). The CPP is evoked following high cervical (segment C2) hemisection from the midline to the lateral edge of the spinal cord (C2HS). This injury removes bulbospinal projections to the ipsilateral phrenic motor pool and thus silences the ipsilateral hemidiaphragm. However, following chronic C2HS, ipsilateral phrenic motor output is gradually enhanced via endogenous mechanisms (Nantwi et al., 1999). Thus, weeks–months post-injury, inspiratory bursting resumes in ipsilateral phrenic motoneurons, even during conditions of quiet breathing (i.e. normoxic normocapnia). The appearance of the crossed phrenic phenomenon is variable across published reports in males (Fuller et al., 2003; Golder and Mitchell, 2005) vs. females (Golder et al., 2001; Nantwi et al., 1999; Vinit et al., 2006). However, it is difficult to directly compare these results due to variance in the rat strain and/or substrain (Fuller et al., 2001), laboratory housing conditions, spinal cord lesion and verification methods, experimental protocols and neurophysiological recording conditions. We hypothesized that recovery of ventilation and phrenic motor output after C2HS differs between males and females, and recovery of these parameters is blunted by prior ovariectomy (OVX) in females.

2. Methods

2.1. Overview

Experiments were conducted using age matched adult (age 4±0.5 months) male and female Sprague–Dawley rats obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA, USA; colony Raleigh R04). Experiments were designed to determine if recovery of phrenic motor output and ventilation after C2HS differs between males and ovary-intact or OVX females. In these experiments, breathing was assessed with whole-body plethysmography prior to all survival surgeries (C2HS or OVX), 1 week following OVX (prior to subsequent C2HS), and 2 weeks following C2HS. Plethysmography data were obtained from male (n = 8), female (n = 7), and OVX female rats (n = 8). Phrenic motor output was measured 2 weeks following C2HS in anesthetized male (n = 10), female (n = 11), and OVX female rats (n = 10).

2.2. Spinal cord injury

Isoflurane anesthesia was induced in a closed chamber and then maintained at 2–3% via a nose cone. Following laminectomy and durotomy, the spinal cord was hemisected on the left side just caudal to the C2 dorsal roots. The spinal cord was incised with a spring scissors and an approximately 1 mm gap was created at the incision site using a pulled micropipette and suction. The overlying muscles were closed with polyglycolic acid suture (4-0 vicryl) and 9 mm wound clips were used to close the skin. Following surgery, an analgesic (buprenorphine, 0.03 mg/kg, s.q.) and an anti-inflammatory drug (carprofen, 5.0 mg/kg, s.q.) were given every 10–12 h for 2 days. Lactated ringers solution (18 mL/day, s.q.) was provided for 1–3 days, until adequate volitional drinking resumed.

2.3. Ovariectomy

Isoflurane anesthesia was induced and maintained as described above. A midline dorsal skin incision (approximately 20 mm) was made over the lumbar spine (L1–L3) followed by an approximately 10 mm incision of the abdominal wall. The latter incision was made 15–20 mm lateral from the dorsal midline. The ovary was drawn out of the abdominal cavity, the uterine horn was ligated, and the ovary was removed. The remaining tissue was replaced in the abdominal cavity and the muscle layer closed (4-0 vicryl). Without making another dorsal skin incision, a second incision of the contralateral abdominal wall was made to extract the remaining ovary (same surgical approach described above). The skin incision was then closed with 9 mm wound clips. Following surgery, rats were given buprenorphine (0.03 mg/kg, s.q.) and carprofen (5.0 mg/kg, s.q.) at 12 h intervals for 2 days.

2.4. Estrous cycle

Female rats have a short estrous cycle and ovulate every 4–5 days (Freeman, 1994). Plasma levels of progestins and estrogens fluctuate dramatically across the particular phases of the cycle (Freeman, 1994). Accordingly, the particular stage of the estrous cycle was determined in female rats at the following time points: immediately prior to C2HS, prior to all plethysmography measurements and prior to neurophysiology experiments. The method was adapted from Zabka et al. (2001). Vaginal epithelial cells were collected via lavage and examined under light microscopy. Rats were considered to be in estrous, diestrous or proestrous based on the appearance of epithelial cell morphology as previously described (Freeman, 1994). All ventilation and phrenic neurogram data (see below) collected in OVX-intact female rats were initially grouped according to the estrous phase at both the time of injury and the time of data collection. However, we were unable to detect a significant effect of the estrous phase on ventilation or phrenic output, and accordingly all female data were grouped.

2.5. Plasma hormone measurement

Terminal blood samples (5–10 mL) were drawn under urethane or isoflurane anesthesia via the femoral artery or inferior vena cava. Samples were allowed to coagulate and centrifuged to collect plasma and stored at −80 C. Estradiol and progesterone levels were analyzed with commercially available clinical ELISA kits (IBL America, Minneapolis, MN) and a Versamax tunable microplate reader running SOFTmax PRO Version 3.0 software (Molecular Devices Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA). Third party positive control samples (Lyphocheck Immunoassay Plus Controls, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Irvine, CA) were used in each assay to ensure quality.

2.6. Plethysmography

A commercially available whole-body plethysmography system (Buxco Inc., Wilmington, NC, USA) was used to quantify ventilation. The plethysmograph was calibrated by injecting known volumes of gas into a Plexiglas recording chamber using a 5-mL syringe. The chamber pressure, temperature and humidity, rectal temperature of the rat, and atmospheric pressure were used in the equation described by Drorbaugh and Fenn (1955) to calculate respiratory volumes including ventilation (VE, mL/min per 100 g) and tidal volume (VT, mL per 100 g). Overall breathing frequency (fR, min−1), the duration of inspiration and expiration, and peak airflow rates were calculated from the airflow traces, which were continuously sampled at 500 Hz. Oxygen consumption (VO2) was measured by sampling the fractional concentration of O2 entering and exiting the plethysmograph chamber. During the experiments, gas mixtures flowed through the chamber at a rate of 2 L/min to enable control of inspired gases. Baseline recordings lasted 1–1.5 h, and were made while the chamber was flushed with 21% O2 (balance N2) (i.e. eucapnic normoxia). Rats were then exposed to hypercapnic gas for 10 min (7% CO2, 21% O2, and balance N2). Rectal temperature was measured immediately before rats were placed in the chamber and again immediately after the hypercapnic exposure. If body temperature had changed by more than 0.1 °C, the equation published by Drorbaugh and Fenn (1955) was used to recalculate the hypercapnic respiratory volumes using the new temperature.

2.7. Neurophysiology

These methods have been described recently (Doperalski and Fuller, 2006). Isoflurane anesthesia was induced in a closed chamber and rats were then transferred to a nose cone where they continued to inhale 2–3% isoflurane. The trachea was then cannulated, the vagus nerves were sectioned in the mid-cervical region, and rats were mechanically ventilated throughout the experimental protocol. A catheter was inserted into the femoral vein (PE-50 tubing), and rats were converted from isoflurane to urethane anesthesia (1.6 g/kg, i.v.; 0.12 g/mL distilled water). Supplemental urethane was given if indicated (0.3 g/kg, i.v.). A femoral arterial catheter (PE-50) was inserted and used to measure blood pressure (Statham P-10EZ pressure transducer, CP122 AC/DC strain gage amplifier, Grass Instruments, West Warwick, RI, USA) and to periodically withdraw blood samples. Rats were paralyzed with pancuronium bromide (3.5 mg/kg, i.v.) and a mixture of lactated Ringer's and 8.4% sodium bicarbonate (3:1) was infused via the venous catheter at 1.5 mL/h. Partial pressures of arterial O2 (PaO2 ) and CO2 (PaCO2 ) as well as pH were periodically determined from 0.1 mL arterial blood samples (i-Stat, Heska, Fort Collins, CO, USA). End-tidal CO2 partial pressure (PETCO2) was measured throughout the protocol using a mainstream CO2 analyzer on the expired line of the ventilator circuit ∼2cm from the tracheostomy tube (Capnogard neonatal CO2 monitor, Novametrix Medical Systems, Wallingford, CT, USA). Rectal temperature was maintained at 37±1.5 °C using a rectal thermistor connected to a servo-controlled heating pad (model TC-1000, CWE Inc., Ardmore, PA, USA).

Both phrenic nerves were isolated in the caudal neck region, and throughout the manuscript, the terms “ipsilateral” and “contralateral” are used to identify the phrenic nerves relative to the C2HS. The ipsilateral nerve was always the left phrenic nerve, and the contralateral nerve was always the right phrenic nerve. Electrical activity was recorded using silver wire electrodes, amplified (1000×), and band pass (300–10,000 Hz) and notch (60 Hz) filtered using a differential A/C amplifier (Model 1700, A-M Systems, Carlsborg, WA, USA). The amplified signal was full-wave rectified, moving averaged (time constant 100 ms), and further amplified (10×) using a model MA-1000 moving averager (CWEInc., Ardmore, PA, USA). Data were digitized using a CED Power 1401 data acquisition interface and recorded on a PC (sample rate 3.3 kHz) using Spike2 software (Cambridge Electronic Design Limited, Cambridge, England).

After an adequate plane of anesthesia was established, the PETCO2 was maintained at 40±2 mmHg for ∼45 min. The PETCO2 threshold for inspiratory phrenic activity was then determined by gradually increasing the ventilator pump rate until inspiratory bursting ceased in both phrenic nerves. After ∼1 min, the ventilator rate was gradually decreased until inspiratory bursting resumed in the contralateral phrenic nerve. The PETCO2 was then maintained 2 mmHg above the value associated with the onset of contralateral inspiratory bursting by adjusting the ventilator rate. After a 30 min baseline period, an arterial blood sample was drawn. Rats were then exposed to a 4 min period of hypoxia (FIO2 = 0.12–0.14), and a blood sample was obtained during the final minute. After 10 min rats were exposed to a 5 min bout of hypercapnia (PETCO2 ∼80 mmHg) achieved by raising the inspired CO2 concentration. Ten minutes after the hypercapnic exposure, a brief asphyxic challenge was performed by stopping the ventilator for 10–20 s. After the asphyxic challenge, a 5–10 mL arterial blood sample was collected for subsequent analysis of estrogen and progesterone concentration. An adequate depth of anesthesia was confirmed and rats were euthanized by systemic perfusion with heparinized saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde.

2.8. Spinal cord histology

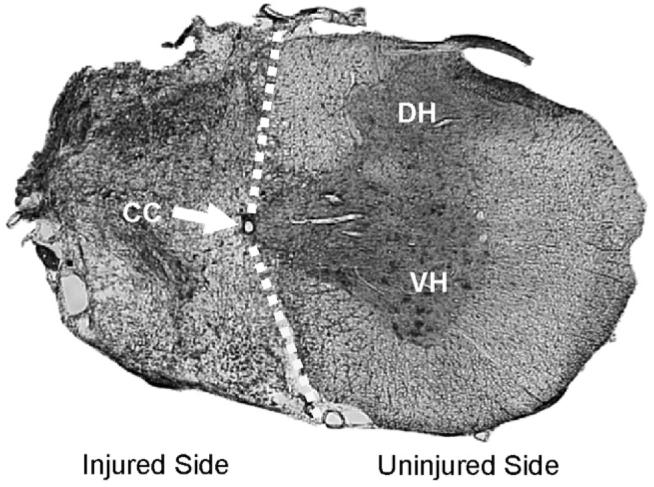

Urethane-anesthetized rats (see above) were perfused with heparinized saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. The cervical spinal cord was removed, cryoprotected and sectioned at 40–50 μm using a cryostat. Tissue sections were mounted on glass slides and then stained with luxol fast blue followed by cresyl violet. Sections were examined with light microscopy to confirm an anatomically complete C2HS. Rats with evidence of healthy white matter in the ipsilateral spinal cord at the lesion epicenter were excluded from the study. All injured rats included in the analyses had a histologically verified C2HS lesion (e.g. Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A representative histological section depicting a C2HS injury. This section was taken from cervical segment C2 in a female rat. The tissue was stained with luxol fast blue and cresyl violet. The absence of healthy tissue on the ipsilateral spinal cord indicates an anatomically complete C2HS. The injured side is occupied by a fibrotic scar characterized by a dense accumulation of mesodermal cells and collagen. The scale bar indicates 1 mm. The dashed line approximates the demarcation between the injured and uninjured sides of the spinal cord; CC indicates the central canal; DH indicates the dorsal horn of the spinal cord; VH indicates the ventral horn of the spinal cord.

2.9. Data analyses

Plethysmography data were analyzed using custom software (Buxco Inc.). Data were averaged over a 10 min period prior to hypercapnia (i.e. baseline), and over the last 5 min of the hypercapnic challenge. Respiratory volume data were expressed per 100 g body mass (Olson et al., 2001). A two-way repeated measures analyses of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Student–Neuman–Keuls post hoc test was used to compare ventilation data before and after C2HS: factor 1 = time (pre- or post-injury), factor 2 = treatment group (male, female or OVX female). To facilitate comparisons across experimental groups, the post-injury data were also expressed relative to the pre-injury measurements as follows: ([post-injury − pre-injury]/pre-injury)×100. These data were compared across groups using a one-way ANOVA.

The frequency and amplitude of moving averaged phrenic bursts were analyzed using Spike2 software. Baseline was measured over a 60 s period just prior to hypoxia and 30 s periods at the end of hypoxia and hypercapnia were also assessed. The asphyxic response was assessed by analyzing the peak phrenic burst during the ∼20 s period with the ventilator off. Phrenic burst amplitude is presented in raw (i.e. volts) and normalized units. Increases in ipsilateral phrenic bursting during respiratory challenges could not be normalized to the baseline condition because often baseline bursting was absent. However, bursting was always observed during hypercapnic challenge and we took advantage of this fact to normalize ipsilateral bursting during hypoxia and asphyxia to hypercapnic bursting. Contralateral bursting was always present, and therefore increases in bursting were expressed relative to the baseline. Neurophysiology data were analyzed with two-way repeated measures ANOVA (factor 1 = “condition” [baseline, hypercapnia, etc.]; factor 2 = “treatment” [male, female, etc.]). Treatment differences within conditions were assessed with the Student–Neuman–Keuls post hoc test. Differences were considered statistically significant when the p-value was less then 0.05. All data are presented as the mean±S.E.M.

3. Results

3.1. Body weight and plasma hormones

Prior to injury, age matched male rats (432±6g) were significantly heavier than females (267±4g, p < 0.05). OVX caused an increase in body mass measured 1 week post-surgery (280±6g, +7±2%, p < 0.05 vs. pre-OVX condition). This finding is consistent with prior reports that OVX stimulates appetite and increases body mass (Asarian and Geary, 2006). Male (393±14 g, −7±3%) and female rats (255±5g, −5±1%) showed similar reductions in body mass at 2 weeks post-C2HS (both p < 0.05 vs. pre-injury condition). Female rats pre-conditioned with OVX did not show reduced body mass following subsequent C2HS (282±7g, +1±2% relative to pre-C2HS). Plasma progesterone was lower in female rats pre-conditioned with OVX (35±4 ng/mL) compared to C2HS alone (73±8 ng/mL, p = 0.002). Plasma estradiol was also lower in OVX + C2HS rats (3±2 pg/mL) compared to C2HS alone (12±3 pg/mL, p = 0.032). The plasma progesterone and estradiol values observed after OVX likely reflect extragonadal production from sources such as the adrenal glands (Simpson et al., 2002).

3.2. Ventilation prior to spinal cord injury

Representative airflow traces recorded using plethysmography are provided in Fig. 2. Baseline VE was not different between sexes prior to C2HS (Fig. 3A) although the pattern of breathing was different. Baseline breathing frequency was lower in spinal-intact female vs. male rats (p = 0.041) and tended to be reduced in OVX rats (p = 0.081 vs. males, Fig. 3A). Ovary-intact (p = 0.002) and OVX females (p = 0.003) also had a higher baseline VT compared to males (Fig. 3A). Sex differences were also observed in the hypercapnic ventilatory response in spinal-intact rats (Fig. 3B). Specifically, hypercapnic VE and VT were greater in ovary-intact and OVX females (both p < 0.001 vs. males; Fig. 3B). Relative to ovary-intact females, pre-conditioning with OVX did not significantly influence any of the ventilatory parameters assessed during baseline or hypercapnia in spinal-intact rats (Fig. 3B). Ventilation was also assessed before and after OVX (but prior to C2HS) in the same rats. These experiments found no evidence that OVX influenced baseline or hypercapnic ventilation in spinal-intact rats (data not shown).

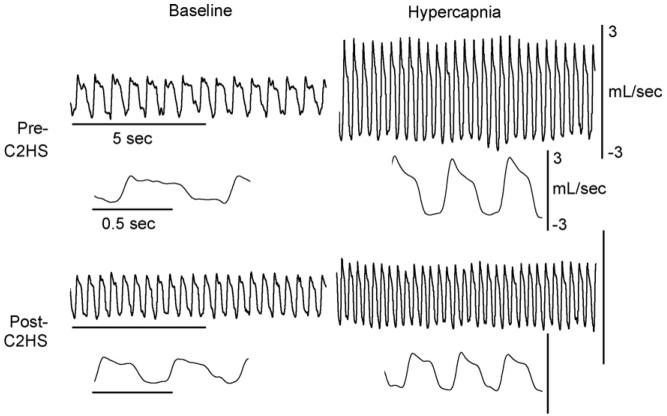

Fig. 2.

Representative airflow traces depicting the impact of C2HS on the pattern of breathing. Data were collected during quiet breathing (baseline) and hypercapnia (7% inspired CO2). Data are presented with two time scales: a compressed file to show many breaths and an expanded trace depicting just a few breaths. All rats were studied both before and 2 weeks following C2HS using a repeated measures approach. These particular data were obtained in a male rat. The scale bars are the same in the top (pre-C2HS) and bottom panels (post-C2HS).

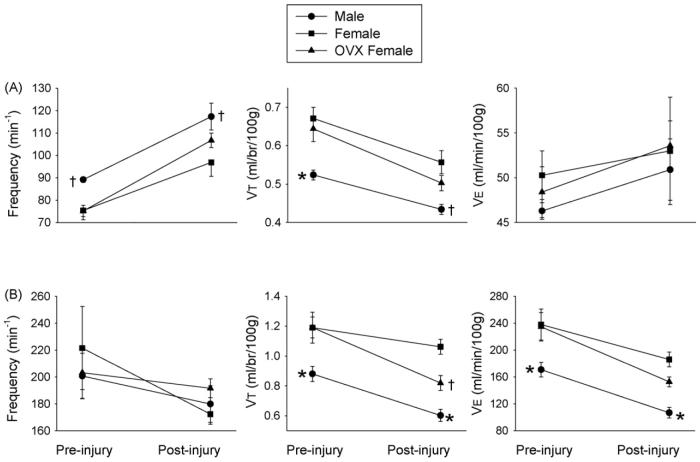

Fig. 3.

The impact of C2HS on ventilation in male rats (●) and both ovary-intact (■) and OVX female rats (▲). Data were collected during a baseline period (21% O2, balance N2) (A) and during a hypercapnic challenge (7% CO2, 21% O2, balance N2) (B). The statistical significance symbols denote differences within each condition (pre- or post-injury) as follows: *, different than ovary-intact and OVX females; †, different than ovary-intact females.

3.3. Ventilation following spinal cord injury

Baseline ventilation was slightly elevated relative to the pre-injury measurement (F1,45 = 4.545, p = 0.046, Fig. 3A), but values were not different across the three experimental groups. The pattern of breathing was also altered as baseline fR (F1,45 = 86.299, p = < 0.001) and VT (F1,45 = 57.195, p < 0.001) were different following C2HS (Fig. 3A). Specifically, baseline fR was increased, and VT decreased in all groups (all p < 0.001 vs. pre-injury). Further, post-injury baseline fR was greater in male vs. ovary-intact (p = 0.010) but not OVX females (p = 0.104, Fig. 3A). Baseline VT was greater in ovary-intact female vs. male rats (p = 0.009), but in contrast to the spinal-intact condition (see above), OVX females no longer had significantly greater VT relative to males (p = 0.075).

The hypercapnic ventilatory response was altered by C2HS (F1,45 = 30.061, p < 0.001). Specifically, each group had reduced VE during hypercapnia (all p < 0.02 vs. pre-injury measurement, Fig. 3B). VE was greater in both ovary-intact (p = 0.001) and OVX females compared to males (p = 0.025). Ovary-intact females tended to have higher hypercapnic ventilation relative to OVX females, but this did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.108). Hypercapnic fR tended to be lower after C2HS (Fig. 3B), but the overall effect was not statistically significant (F1,45 = 4.139, p = 0.055). Thus, the diminished hypercapnic VE primarily reflected a reduction in VT relative to pre-injury values (female rats, p = 0.049, male and OVX females, p < 0.001). A significant interaction for hyper-capnic VT was detected between time (pre-injury vs. post-injury) and treatment (male, female or OVX; F2,45 = 4.266, p = 0.029). Thus, hypercapnic VT was greater in ovary-intact female rats compared to both males (p < 0.001) and OVX females (p = 0.011), a difference that did not exist prior to C2HS (Fig. 3B). Further analyses revealed that the attenuation in VT relative to pre-injury was less in female (−10±5%) than either male (−31±4%) or female OVX rats (−29±3%) (both p < 0.008 vs. ovary-intact females).

3.4. Phrenic motor output in anesthetized rats

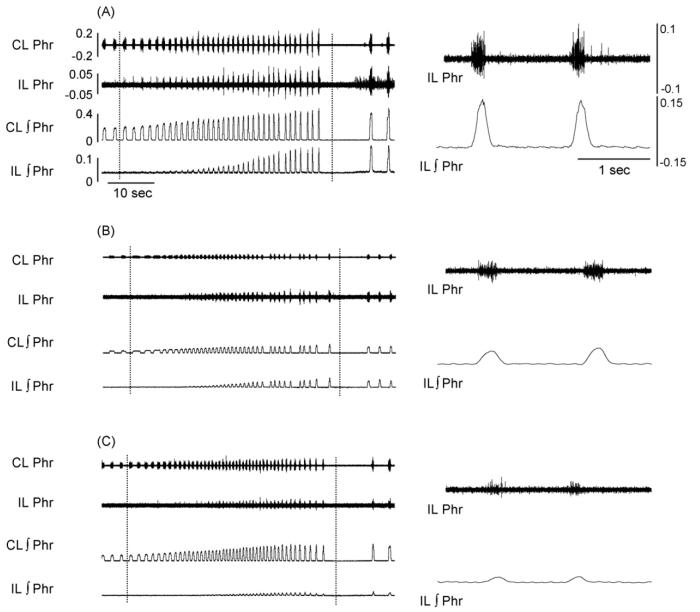

Representative examples of phrenic motor output are provided in Fig. 4. During baseline conditions, the proportion of rats showing inspiratory bursting in the ipsilateral phrenic nerve (i.e. the crossed phrenic phenomenon) was similar in males (6/10), females (6/10) and OVX females (5/10). In the subset of rats with ipsilateral bursting, amplitude was considerably reduced in all groups: male = 9±1%, female = 5±1%, and OVX = 7±2% of contralateral burst amplitude.

Fig. 4.

Representative phrenic neurogram activity in female (A), male (B) and ovariectomized female rats (C). The examples show phrenic activity during a respiratory challenge induced by brief cessation of mechanical ventilation. The panels on the left show an approximately one min data segment obtained just prior to, during, and following the interruption of mechanical ventilation (the period between the dashed lines). This respiratory challenge induced a robust increase phrenic bursting recorded ipsilateral (IL) and contralateral (CL) to the C2HS injury. The right panel depicts two IL phrenic bursts at the end of the challenge using an expanded time scale. Calibration bars are provided for panel A; the amplification and scaling of the data are identical in panels A–C.

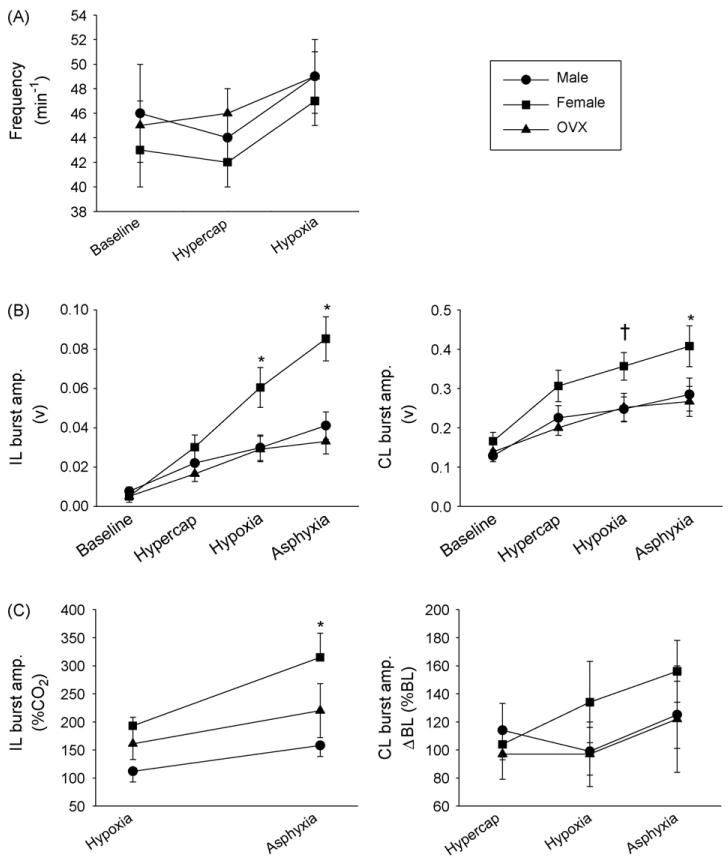

Chemical respiratory challenge was provided by hypoxia, hypercapnia, and “asphyxia” (induced by transiently stopping the mechanical ventilator). Analyses of ipsilateral phrenic burst amplitude (volts) revealed a significant interaction between condition (i.e. baseline, hypercapnia, hypoxia, and asphyxia) and treatment (i.e. male, female or OVX) (F6,112 = 9.491, p < 0.001). That is, the effects of treatment were dependent on the condition. Specifically, burst amplitude differences were not present during baseline and hypercapnia, but during hypoxia and asphyxia females had substantially greater IL phrenic burst amplitude (all p < 0.006, Fig. 5B, left panel). Importantly, this finding was confirmed by the normalized phrenic burst data as follows. Ipsilateral phrenic burst data could not be expressed relative to baseline values because many rats did not have bursting during baseline (see above). Accordingly, the data recorded during hypoxic and asphyxic challenges were normalized relative to the hypercapnic condition (during which ipsilateral bursting was similar between groups, Fig. 5B, left panel). With this approach (Fig. 5C, left panel), the overall effect for treatment group (male vs. female vs. OVX) was significant (F2,53 = 5.168, p = 0.014), and post hoc tests revealed that bursting during asphyxic challenge was greater in females compared to both male (p = 0.003) and OVX females (p = 0.042).

Fig. 5.

The impact of sex and ovariectomy on phrenic output after C2HS. Data were collected in anesthetized male rats (●) and both ovary-intact (■) and OVX female rats (▲). Burst frequency is presented in panel A for the conditions of baseline, hypercapnia and hypoxia. The raw and normalized phrenic neurogram burst amplitudes are presented in panels B and C, respectively. Ipsilateral (IL) bursting is shown in the left panels; contralateral (CL) bursting in the right panels. Please see Section 2 for a description of normalization procedures. The statistical significance symbols denote differences within each condition as follows: *, different than males and OVX females; †, different than OVX females.

A significant interaction between condition and treatment was also observed for contralateral phrenic burst amplitude (F6,119 = 2.348, p = 0.038). Post hoc tests indicated that contralateral burst amplitude (volts) was significantly elevated in females compared to males (p = 0.013) and OVX females (p = 0.022) during the asphyxic challenge (Fig. 5B, right panel). During hypoxia, contralateral bursting was elevated in females vs. OVX females (p = 0.045), but differences between females and males were not statistically significant (p = 0.066). However, no differences in contralateral burst amplitude were observed across the three groups when the data were normalized relative to baseline bursting (Fig. 5C, right panel). Despite this, we felt it was important to at least report the raw burst amplitude data particularly since these data were collected in a random fashion with male, female and OVX female rats interspersed. No differences in phrenic burst frequency were observed between experimental groups (F2,95 = 0.567, p = 0.569, Fig. 5A).

Arterial blood gases measured during neurophysiology experiments are presented in Table 1. PaO2 and pH were similar across experimental groups and conditions, however, PaCO2 was slightly lower during baseline in male C2HS rats (p < 0.05 vs. other groups Table 1). PaCO2 dropped by a few mmHg during hypoxia in female and OVX female rats (p < 0.05 vs. baseline). Male rats showed a tendency for reduced PaCO2 during hypoxia but the drop was not statistically significant (Table 1).

Table 1.

Arterial blood gases recorded during neurophysiology experiments in anesthetized rats

| Group | Condition | PaO2 (mmHg) | PaCO2 (mmHg) | pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Baseline | 115 ± 4 | 37 ± 1‡ | 7.39 ± 0.01 |

| Hypoxia | 32 ± 1* | 35 ± 1 | 7.39 ± 0.01 | |

| Female | Baseline | 120 ± 3 | 41 ± 1 | 7.38 ± 0.01 |

| Hypoxia | 32 ± 1* | 38 ± 1* | 7.39 ± 0.01 | |

| OVX | Baseline | 117 ± 6 | 43 ± 2 | 7.39 ± 0.01 |

| Hypoxia | 34 ± 1* | 38 ± 1* | 7.39 ± 0.02 |

Data were obtained during baseline conditions, brief hypoxic challenge and during the post-hypoxic period. Values are means ± S.E.

Different than baseline

different than corresponding data point in the other two groups.

4. Discussion

These experiments show that C2HS-induced changes in the pattern of breathing differ between male and female rats. In particular, the post-injury reductions in VT observed during hypercapnic challenge were more pronounced in male vs. female rats. This gender difference was reduced considerably when female rats were preconditioned with OVX suggesting that it may have been mediated by ovarian sex hormones (e.g. estrogen and progesterone). This hypothesis will need to be addressed more directly in the future by combining OVX with hormone replacement. The enhanced recovery of VT observed in female rats may reflect increased phrenic output as an augmented crossed phrenic response was observed in ovary-intact females during respiratory challenge.

4.1. C2HS and phrenic output

The apparent impact of ovarian sex hormones on ventilation after SCI (e.g. Fig. 3) could reflect muscular and/or neural mechanisms of plasticity. To determine if neural mechanisms could be involved we examined phrenic motor output in anesthetized rats. Both raw and normalized ipsilateral phrenic burst amplitudes following C2HS were larger in female vs. male rats under carefully controlled conditions. Thus, the crossed phrenic phenomenon may be influenced by sex hormones, at least when studied at 2 weeks post-injury. Consistent with this suggestion, pre-conditioning with OVX reduced ipsilateral phrenic motor output after C2HS (i.e. the crossed phrenic phenomenon) in female rats. In fact, ipsilateral phrenic output in OVX rats looked quite similar to what was observed in male rats.

The current data are consistent with the notion that crossed phrenic activity can, under some conditions, make a meaningful contribution to ventilation (Fuller et al., 2008). Consistent with this idea, Golder et al. (2003) demonstrated that ipsilateral phrenic output enabled anesthetized female rats to generate large inspiratory volumes at 8 weeks post-injury although earlier time points were not assessed. Prior studies in male rats indicate that the crossed phrenic phenomenon makes little, if any contribution to ventilation over the initial few weeks post-injury (Fuller et al., 2006). However, crossed phrenic activity may contribute to increased respiratory volumes by 2–3 months post-injury in male rats (Fuller et al., 2008). Collectively, these data suggest that the crossed phrenic phenomenon is capable of making a functional impact on ventilation, however the post-injury time course of such an impact may differ between male and female rats.

4.2. Sex hormones and respiratory recovery

Our finding that respiratory recovery differs between males and females is consistent with prior investigations of different motor systems. For example, Hauben et al. (2002) found that female rats and mice recover locomotor function significantly better than male littermates following incomplete SCI. A similar result was obtained by Farooque et al. (2006) who reported impaired motor and histological outcomes after SCI in male compared to female mice. Bramlett and Dietrich (2001) observed improved histological outcomes after traumatic brain injury in female vs. male rats. Further, OVX impairs motor recovery following experimental stroke and focal brain ischemia (Alkayed et al., 1998; Zhang et al., 1998). Accordingly, female sex hormones appear to offer some form of neuroprotection after central nervous system injury. However, in regard to the present data set another strong possibility is that sex hormones directly or indirectly influenced respiratory control after SCI but did not offer neuroprotection per se. Prior work establishes that sex hormones influence the control of breathing (Dempsey et al., 1986; Tatsumi et al., 1995; Behan et al., 2003) but to our knowledge this is the first study to explore sex differences in breathing after SCI. In this regard, it is particularly relevant that sex hormones can influence the expression of plasticity in respiratory motor control (reviewed in Behan et al., 2002, 2003). The current data suggest that the crossed phrenic phenomenon can be influenced by sex hormones, at least under certain conditions (Fig. 3), and this finding is consistent with a role of sex hormones in the expression of respiratory neuroplasticity.

Prior reports of plasma progesterone and estradiol in rats are somewhat variable (Cameron et al., 2002; Blair and Mickelsen, 2006; Donadio et al., 2006; Jazbutyte et al., 2006; Bernuci et al., 2008). This variability may reflect differences in rat strain, the time of day and/or the particular estrous cycle phase during sampling (Freeman, 1994). In any case, direct comparisons of plasma hormone values with our data are difficult as we are unaware of any prior measures of progesterone and estradiol following high cervical SCI in rats. Nevertheless, the values reported here are within the ranges of previous reports (Freeman, 1994; Kovacic et al., 2004) and the data confirm that pre-conditioning with OVX reduced plasma progesterone and estradiol compared to females receiving only C2HS.

The potential mechanisms by which sex hormones influence the control of breathing are not precisely known. Behan et al. (2003) propose that sex hormones act throughout the neuraxis to affect the control of ventilation. For example, the function of respiratory motoneurons, premotoneurons, brainstem respiratory rhythm generating neurons, and relevant neuromodulatory systems (e.g. serotonergic neurons; Zabka et al., 2006) could all be influenced by sex hormones.

4.3. Physiological significance

Approximately one-half of all SCI's occur in the cervical region and respiratory-related problems are significant after SCI (Winslow and Rozovsky, 2003). Accordingly, there is considerable interest in preclinical animal models of respiratory (dys)function after SCI (reviewed in Goshgarian, 2003; Zimmer et al., 2007, 2008). Our data indicate that sex should be considered a relevant variable in preclinical research examining mechanisms underlying respiratory motor recovery after cervical SCI.

Acknowledgements

We thank Sandy Walker for help with data collection and Cathy Thomas and Drs. Andrea Zabka and Mary Behan for help with the estrous cycle staging method and ELISA measurement. This work was supported by NIH RO3 NS050684-01A1 (DDF), a seed grant from the American Paraplegia Society (DDF), and NIH R01 NS054025-01 (PJR).

References

- Alkayed NJ, Harukuni I, Kimes AS, London ED, Traystman RJ, Hurn PD. Gender-linked brain injury in experimental stroke. Stroke. 1998;29:159–165. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.1.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asarian L, Geary N. Modulation of appetite by gonadal steroid hormones. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2006;361:1251–1263. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavis RW, Kilgore DL., Jr. Effects of embryonic CO2 exposure on the adult ventilatory response in quail: does gender matter? Respir. Physiol. 2001;126:183–199. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(01)00206-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavis RW, Olson EB, Jr., Vidruk EH, Fuller DD, Mitchell GS. Developmental plasticity of the hypoxic ventilatory response in rats induced by neonatal hypoxia. J. Physiol. 2004;557:645–660. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.061408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behan M, Zabka AG, Mitchell GS. Age and gender effects on serotonin-dependent plasticity in respiratory motor control. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2002;131:65–77. doi: 10.1016/s1569-9048(02)00038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behan M, Zabka AG, Thomas CF, Mitchell GS. Sex steroid hormones and the neural control of breathing. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2003;136:249–263. doi: 10.1016/s1569-9048(03)00086-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernuci MP, Szawka RE, Helena CVV, Leite CM, Lara HE, Anselmo-Franci JA. Locus coeruleus mediates cold stress-induced polycystic ovary in rats. Endocrinology. 2008;149:2907–2916. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair ML, Mickelsen D. Plasma protein and blood volume restitution after hemorrhage in conscious pregnant and ovarian steroid-replaced rats. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2006;290:R425–R434. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00011.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramlett HM, Dietrich WD. Neuropathological protection after traumatic brain injury in intact female rats versus males or ovariectomized females. J. Neurotrauma. 2001;18:891–900. doi: 10.1089/089771501750451811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron VA, Autelitano DJ, Evans JJ, Ellmers LJ, Espiner EA, Nicholls MG, Richards AM. Adrenomedullin expression in rat uterus is correlated with plasma estradiol. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002;282:E139–E146. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2002.282.1.E139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey JA, Olson EB, Skatrud JB. Hormones and neurochemicals in the regulation of breathing. In: Cherniack NS, Widdicombe JG, editors. Handbook of Physiology, Section 3: The Respiratory System, Volume II: Control of Breathing. Part 1. American Physiological Society; Washington, DC: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Donadio MV, Gomes CM, Sagae SC, Franci CR, Anselmo-Franci JA, Lucion AB, Sanvitto GL. Estradiol and progesterone modulation of angiotensin II receptors in the arcuate nucleus of ovariectomized and lactating rats. Brain Res. 2006;1083:103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doperalski NJ, Fuller DD. Long-term facilitation of ipsilateral but not contralateral phrenic output after cervical spinal cord hemisection. Exp. Neurol. 2006;200:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drorbaugh JE, Fenn WO. A barometric method for measuring ventilation in newborn infants. Pediatrics. 1955;16:81–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farooque M, Suo Z, Arnold PM, Wulser MJ, Chou CT, Vancura RW, Fowler S, Festoff BW. Gender-related differences in recovery of locomotor function after spinal cord injury in mice. Spinal Cord. 2006;44:182–187. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman ME. The neuroendocrine control of the ovarian cycle of the rat. In: Knobi E, Neill JD, editors. The Physiology of Reproduction. 2nd ed. Raven Press, Ltd.; New York, NY: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller DD, Baker TL, Behan M, Mitchell GS. Expression of hypoglossal long-term facilitation differs between substrains of Sprague–Dawley rat. Physiol. Genomics. 2001;4:175–181. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.2001.4.3.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller DD, Johnson SM, Olson EB, Jr., Mitchell GS. Synaptic pathways to phrenic motoneurons are enhanced by chronic intermittent hypoxia after cervical spinal cord injury. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:2993–3000. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-07-02993.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller DD, Golder FJ, Olson EB, Jr., Mitchell GS. Recovery of phrenic activity and ventilation after cervical spinal hemisection in rats. J. Appl. Physiol. 2006;100:800–806. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00960.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller DD, Doperalski NJ, Dougherty BJ, Sandhu MS, Bolser DC, Reier PJ. Modest spontaneous recovery of ventilation following chronic high cervical hemisection in rats. Exp. Neurol. 2008;211:97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golder FJ, Mitchell GS. Spinal synaptic enhancement with acute intermittent hypoxia improves respiratory function after chronic cervical spinal cord injury. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:2925–2932. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0148-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golder FJ, Fuller DD, Davenport PW, Johnson RD, Reier PJ, Bolser DC. Respiratory motor recovery after unilateral spinal cord injury: eliminating crossed phrenic activity decreases tidal volume and increases contralateral respiratory motor output. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:2494–2501. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02494.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golder FJ, Reier PJ, Bolser DC. Altered respiratory motor drive after spinal cord injury: supraspinal and bilateral effects of a unilateral lesion. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:8680–8689. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-21-08680.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshgarian HG. The crossed phrenic phenomenon: a model for plasticity in the respiratory pathways following spinal cord injury. J. Appl. Physiol. 2003;294:795–810. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00847.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauben E, Mizrahi T, Agranov E, Schwartz M. Sexual dimorphism in the spontaneous recovery from spinal cord injury: a gender gap in beneficial autoimmunity? Eur. J. Neurosci. 2002;16:1731–1740. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jazbutyte V, Hu K, Kruchten P, Bey E, Maier SKG, Fritzemeier K-H, Prelle K, Hegele-Hartung C, Hartmann RW, Neyses L, Ertl G, Pelzer T. Aging reduces the efficacy of estrogen substitution to attenuate cardiac hypertrophy in female spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2006;48:579–586. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000240053.48517.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph V, Soliz J, Pequignot J, Sempore B, Cottet-Emard JM, Dalmaz Y, Favier R, Spielvogel H, Pequignot JM. Gender differentiation of the chemoreflex during growth at high altitude: functional and neurochemical studies. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2000;278:R806–R816. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.278.4.R806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacic U, Zele T, Osredkar J, Sketelj J, Bajrovic FF. Sex-related differences in the regeneration of sensory axons and recovery of nociception after peripheral nerve crush in the rat. Exp. Neurol. 2004;189:94–104. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montandon G, Bairam A, Kinkead R. Long-term consequences of neonatal caffeine on ventilation, occurrence of apneas, and hypercapnic chemoreflex in male and female rats. Pediatr. Res. 2006;59:519–524. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000203105.63246.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nantwi K, El-bohy AA, Schrimsher GW, Reier PJ, Goshgarian HG. Spontaneous recovery in a paralyzed hemidiaphragm following upper cervical spinal cord injury in adult rats. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair. 1999;13:225–234. [Google Scholar]

- Olson EB, Jr., Bohne CJ, Dwinell MR, Podolsky A, Vidruk EH, Fuller DD, Powell FL, Mitchell GS. Ventilatory long-term facilitation in unanesthetized rats. J. Appl. Physiol. 2001;91:709–716. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.2.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson ER, Clyne C, Rubin G, Boon WC, Roberstson K, Britt D, Speed C, Jones M. Aromatase—a brief overview. Ann. Rev. Physiol. 2002;64:93–127. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.081601.142703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatsumi K, Moore LG, Hannhart B. Influences of sex steroids on ventilation and ventilatory control. In: Dempsey JA, Pack AI, editors. Regulation of Breathing. Marcel Dekker; New York, NY: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Vinit S, Gauthier P, Stamegna JC, Kastner A. High cervical lateral spinal cord injury results in long-term ipsilateral hemidiaphragm paralysis. J. Neurotrauma. 2006;23:1137–1146. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winslow C, Rozovsky J. Effect of spinal cord injury on the respiratory system. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2003;82:803–814. doi: 10.1097/01.PHM.0000078184.08835.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabka AG, Behan M, Mitchell GS. Time-dependent hypoxic respiratory responses in female rats are influenced by age and by the estrus cycle. J. Appl. Physiol. 2001;91:2831–2838. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.6.2831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabka AG, Mitchell GS, Behan M. Ageing and gonadectomy have similar effects on hypoglossal long-term facilitation in male Fischer rats. J. Physiol. 2005;563:557–568. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.077511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabka AG, Mitchell GS, Behan M. Conversion from testosterone to oestradiol is required to modulate respiratory long-term facilitation in male rats. J. Physiol. 2006;576:903–912. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.114850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YQ, Shi J, Rajakumar G, Day AL, Simpkins JW. Effects of gender and estradiol treatment on focal brain ischemia. Brain Res. 1998;784:321–324. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00502-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer MB, Nantwi K, Goshgarian HG. Effect of spinal cord injury on the respiratory system: basic research and current clinical treatment options. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2007;30:319–330. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2007.11753947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer MB, Nantwi K, Goshgarian HG. Effect of spinal cord injury on the neural regulation of respiratory function. Exp. Neurol. 2008;209:399–406. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]