Abstract

Multiplex families ascertained through multiple alcohol dependent individuals appear to transmit alcohol and drug use disorders at higher rates than randomly selected families of alcoholics. Our goal was to investigate the risk of developing specific psychiatric diagnoses during childhood or adolescence in association with familial risk status (high-risk [HR] or low-risk [LR]) and parental diagnosis.

Using a prospective longitudinal design, HR offspring from three generation multiplex alcohol dependence families and LR control families were followed yearly. Data analysis was based on consensus diagnoses from 1738 yearly evaluations conducted with the offspring and a parent using the K-SADS, and separately modeled the effects of familial susceptibility and exposure to parental alcohol dependence. Multiplex family membership and parental alcohol and drug dependence significantly increased the odds that offspring would experience some form of psychopathology during childhood or adolescence, particularly externalizing disorders. Additionally, parental alcohol dependence increased the odds that adolescent offspring would have major depressive disorder (MDD). While it is well known that parental substance dependence is associated with externalizing psychopathology, the increased risk for MDD seen during adolescence in the present study suggests the need for greater vigilance of these children.

Keywords: alcohol dependence, multiplex, high-risk, children, adolescents, psychopathology, genetic

1. Introduction

It has long been known that first-degree relatives of alcohol or drug dependent probands have an increased risk for developing alcoholism (Hill et al., 1977; Merikangas et al., 1998) and drug dependence (Hill et al., 1977; Croughan, 1985) over that seen in the general population. Genetic influence on substance use disorders are well established based on comparisons of rates of these disorders in monozygotic and dizygotic twins (Gurling et al., 1985; Tsuang et al., 1998; Kendler et al., 2000) and in adopted away offspring of biological parents with alcoholism (Goodwin et al., 1973) and drug dependence (Cadoret et al., 1996).

Multiplex families ascertained through multiple alcohol dependent individuals appear to transmit alcohol and drug use disorders at even higher rates than randomly selected families of alcoholics (Hill and Muka, 1996; Hill et al., 1999a), providing an opportunity for identification of neurobiological markers and genetic polymorphisms for disease susceptibility (Morton and Mi, 1968; Smalley et al., 2000; Seidman et al., 2002). Genes contributing to susceptibility for adult onset alcohol dependence may have pleiotropic effects in childhood that increase risk for a broad spectrum of child and adolescent psychopathology. Obtaining a better understanding of this relationship will require uncovering reliable rates of illness in offspring.

Variation in reported rates of child psychiatric disorders in children of AD parents has been noted (Kuperman et al., 1999). Among the factors influencing reported rates are the presence of comorbid psychiatric illness in the AD parent, variation in sample origin (treated versus untreated), and use of relatively small samples. The ascertainment schema used (multiplex versus random samples of unselected alcoholics) may also be an important source of variation. Recent reports from the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism (COGA) study (Kuperman et al., 1999; Ohannessian et al., 2004) and those from our samples (Hill and Muka, 1996; Hill et al 1999a) are based on offspring from multiplex families. Offspring from unselected families of alcohol dependent parents can be expected to have fewer AD relatives and may have a less severe form of the disorder.

In spite of the varied nature of sample selection, overall, children of alcohol and drug dependent individuals appear to have an increased risk for developing externalizing disorders including elevations in Conduct Disorder (CD), Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD), and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) (Earls et al., 1988; Reich et al., 1993; Hill and Muka, 1996; Hill et al., 1999a; Kuperman et al., 1999; Merikangas and Avenevoli, 2000; Ohannessian et al., 2004). Elevations in internalizing disorders have also been noted, particularly for overanxious disorder (Reich et al., 1993) and affective disorders (Hill et al., 1999a).

Although there is general agreement that high risk offspring are more prone to experience disorders during childhood and adolescence, significant gaps in our knowledge of specific risk factors associated with development of child and adolescent disorders persist. Complicating the study of increased genetic susceptibility for alcohol dependence (AD) using offspring from families with multiple cases of AD is the concurrent environmental exposure to AD relatives that often results in greater adversity, especially if the relative is a parent. Although gene by environment interactions have been demonstrated for alcohol dependence and other psychiatric disorders, specifying salient environmental influences has been challenging for the field (Gunzerath and Goldman, 2003). Among the issues needing further study are the role of familial/genetic loading for alcoholism versus the influence of parental alcohol dependence, and more specifically the role of maternal versus paternal alcohol dependence. Additionally, the possible contribution of parental comorbid conditions in the development of these disorders, and the temporal progression of psychopathology in childhood and adolescence have largely been unexplored. With two large-scale family studies ongoing in our laboratory in which third generation offspring have been evaluated longitudinally through childhood and adolescence, we were in a position to begin to answer some of these questions. Moreover, because one of the studies ascertained families through the presence of a pair of adult alcohol dependent sisters, while the other selected families through the presence of a pair of adult alcohol dependent brothers, we were in a position to compare the influence of parental alcohol dependence by gender.

2. Methods

2.1. Description of Family Studies

The high and low-risk (control) children/adolescents were participants in one of two ongoing family studies (Cognitive and Personality Factors in Relatives of Alcoholics family study [CPFFS] and the Biological Risk Factors in Relatives of Alcoholic Women family study [BRFFS]). The high-risk families had been identified through a proband pair of alcohol dependent siblings. One member of the pair was in a substance abuse treatment facility in the Pittsburgh area at the time of recruitment (late 1980’s and early 1990’s). Probands were screened (Diagnostic Interview Schedule [DIS]) (Robins et al., 1981) for the presence of alcohol dependence (AD) and other Axis I (DSM-III) psychopathology (Feighner Criteria for AD was also obtained). Family history information for biological relatives provided screening information to determine if the proband might have a same-sex sibling meeting criteria for alcohol dependence. If this appeared to be the case, the proband assisted in the recruitment of his/her sibling who then completed the same diagnostic assessments.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria for High-Risk Families

Probands and their families were selected if a pair of same-sexed adult siblings with an alcohol dependence diagnosis was present (sister pairs for the BRFFS study and brother pairs for the CPFFS study). Each multiplex family required the screening of approximately 100 families to meet the present goals, and for the broader goals of the family studies that included a search for developmental neurobiological markers (Hill et al., 1999b) and gene finding efforts (Hill et al., 2004).

2.3. Exclusion Criteria for High-Risk Families

The DIS was administered to all available relatives (adult probands, their siblings and parents [>90% of first degree relatives]). Unavailable or deceased relatives were diagnosed using a minimum of two family-history reports. Targeted families were excluded if the proband or his or her first-degree relatives showed evidence of primary recurrent Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), Bipolar Disorder (BD), Primary Drug Dependence (PDD) (i.e., drug dependence preceded alcohol dependence by 1 or more years) or Schizophrenia by DSM-III criteria, the diagnostic system in place at the time the studies were initiated. Presence of Axis II disorders was not used as either an exclusionary or inclusionary condition. No attempt was made to limit the psychiatric disorders in “marrying in” spouses who represent the parents of the children/adolescents reported here. However, available spouses were diagnosed using the same methods (DIS) as members of the “target” families.

2.4. Selection of Control Families

Selection of control families was based on availability of a pair of same sex adult siblings. Selection of families was based on one of two methods. In the first method (Control Group I – CPFFS Study), volunteers were screened for Axis I psychopathology including alcohol and drug dependence using the DIS. Control families were selected if the volunteer’s first-degree relatives (parents and siblings) were similarly free of psychopathology. In the second method (Control Group II – BRFFS Study), volunteers from the same census tract who indicated they had children between the ages of 8–18 years were screened as a potential control family in order to match the family to a high-risk family using census tract information. The control parents of these offspring were screened for parental alcohol or drug dependence. Comparison of control groups I and II did not reveal significant differences in socioeconomic status (mean SES = 44.22 ± 11.8 SD for the CPFFS controls and mean = 45.99 ± 11.66 for the BRFFS controls), or in offspring rates of psychopathology in the two control groups (rates of “any” diagnosis was not significantly different [47.2% for CPFFS and 52.8% for the BRFFS]) allowing for the two control groups to be combined. (While these rates of “any disorder” may appear high for control samples, it should be noted that simple phobia and separation anxiety account for approximately two-thirds of the positive cases in childhood.) Because the likelihood of having any diagnosis was similar in both control groups, the present report is based on the offspring from both types of control families, included in an approximately equal number.

2.5. Participants

The minor offspring of HR proband pairs and their adult siblings along with control offspring are currently being followed in longitudinal initiatives and are the subject of this report. Three generation pedigree information for the HR offspring reveals an average of 4 first and second-degree relatives with alcohol dependence.

A total of 378 children/adolescents (ages 8 to 18) who were either at high (N = 202) or low-risk (N = 176) for developing AD because of multiplex family membership were assessed multiple times (usually annually). High-risk (HR) and low-risk (LR) families had been characterized clinically so that both primary and secondary disorders of the parental generation were known (See Table 1). High-risk offspring from multiplex pedigrees had varying nuclear family characteristics: mother alcohol dependent but father not; father alcohol dependent but mother not; neither alcohol dependent, both alcohol dependent, and one or both unknown (See Table 1). Both studies have ongoing approval from the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. Participants provided informed consent at each follow-up visit. Children provided assent with parental consent.

Table 1.

Alcohol Dependence Diagnoses From Direct Interview of Parents from High Risk Three Generation Pedigrees

| Father Alcohol Dependent | Father Not Alcohol Dependent | Father’s Diagnosis Unknown | Totals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother Alcohol Dependent | 12 (5.9%) | 8 (4.0%) a | 84 (41.6%) b | 104 (51.5%) |

| Mother Not Alcohol Dependent | 31 (15.3%) a | 27 (13.4%) a | 15 (7.4%) | 73 (36.1%) |

| Mother’s Diagnosis Unknown | 15 (7.4%) | 6 (3.0%) | 4 (2.0%) | 25 (12.4%) |

| Totals | 58 (28.7%) | 41 (20.3 %) | 103 (50.9%) | 202 |

One or both parents were not alcohol dependent in 66/202 cases or 32.7% of the high risk offspring studied.

This relatively high rate of unknown diagnoses among fathers was due to the fact that alcohol dependent women in the BRFFS study often did not know the current whereabouts of the biological father in order to obtain direct interview of these men. Moreover, during the time the study was being conducted, the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board decided that obtaining family history information about individuals without their written consent would be prohibited.

A total of 217 offspring (64 male and 60 female HR [multiplex family] and 53 male and 40 female LR controls) between the ages of 8 and 11 years completed an average of 2.04 ± 0.76 yearly evaluations (N = 443 evaluations). A total of 338 offspring between the ages of 12–18 years completed 1295, an average of 3.83 ± 0.12 assessments. These assessments completed during adolescence included 84 male and 98 female HR offspring and 88 male and 68 female LR offspring. A total of 177 participants completed assessments during both childhood and adolescence.

2.6. Retention and Completion of Waves

Because the two studies are pedigree-based, available offspring were of varying ages at study entry and contributed differing number of assessments to the analyses at any particular follow-up date. Retention has been equivalent by risk group for both studies. The HR and LR participants in the BRFFS study completed an average of 3.63 ± 0.22 (SE) waves and 4.35 ± 0.22 (SE) waves, respectively. For the CPFFS the HR subjects completed an average of 6.09 ± 0.35 evaluations while LR subjects completed 4.57 ± 0.39 (SE) evaluations. (To date, the CPFFS follow up has been longer so that a larger number of high-risk evaluations have been completed.) All study participants provided informed consent at each follow-up visit.

2.7. Socioeconomic Status and Ethnicity

Socioeconomic status (SES) was determined for each of the parents using the Four Factor Index of Social Status (Hollingshead, 1975), a summary score based on education and job occupation.

2.8. Child/Adolescent Assessment for DSM-III Diagnoses

Each child/adolescent and his/her parent were separately administered the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (K-SADS) (Chambers et al., 1985) by trained, Masters’ level, clinical interviewers and an advanced resident in child psychiatry at each annual evaluation. Using DSM-III criteria that has been used throughout the follow-up, K-SADS interviewers and the resident independently provided scores for each diagnosis. A best-estimate diagnosis based on these four blinded interviews was completed in the presence of a third clinician who facilitated discussion to resolve diagnostic disagreements if needed.

2.9. Statistical Analyses

A breakdown of parental alcohol dependence diagnoses may be seen in Table 1. Comorbidity is common in samples of male and female alcoholics and can complicate the interpretation of the presumed effects of parental alcohol dependence or familial genetic susceptibility on offspring psychopathology. Therefore, at the inception of the two family studies exclusion criteria were in place to limit comorbidity (Table 2), remaining comorbidity was taken into account statistically.

Table 2.

Lifetime Prevalence of Comorbid Disorders (%) in Parents With and Without Alcohol Dependence

| Fathers (N =206 ) | Mothers (N=330) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol Dependent | Not Alcohol Dependent | Alcohol Dependent | Not Alcohol Dependent | |

| (N= 66) | (N= 140) | (N=113) | (N=217) | |

| Drug Dependence a | 33.3 | 2.1 | 51.8 | 1.4 |

| Major Depression b | 13.6 | 14.3 | 33.6 | 23.0 |

| Anxiety Disorders b | 0.0 | 1.4 | 9.1 | 0.9 |

| Any Axis I Comorbidity c | 37.9 | 16.4 | 70.8 | 25.8 |

| Antisocial Personality Disorder | 34.4 | 0.0 | 34.6 | 0.5 |

secondary drug dependence (note proband alcoholics were selected to be primary for alcohol dependence). Primary was defined by the age of onset of the disorder. Onset of alcohol dependence preceded onset of drug dependence by at least one year to be considered primary. Individuals who were not alcoholic included those from control families and unaffected relatives of alcoholics.

All major depressive disorders and anxiety disorders were secondary as defined by age of onset.

Axis I disorders included in this percentage were drug dependence, major depression, anxiety disorders, mania, and schizophrenia.

The first goal of the analyses was to evaluate the effects of familial risk status on the likelihood that offspring would experience a psychiatric disorder during childhood or adolescence (Table 3 and 4). The second goal was to evaluate the effects of having an alcohol or drug dependent parent, or a parent with depression, on the likelihood that the offspring would experience an adverse psychiatric outcome without stratifying by risk category. Risk status and parental pathology are not synonymous in this sample. Some high-risk offspring from our multiplex pedigrees did not have an alcohol dependent parent (e.g., offspring of the nonalcoholic siblings of proband alcohol dependent individuals). The presence of a disorder at any annual visit during the developmental period of interest (adolescence or childhood) was coded as positive for that period. Odds ratios were adjusted for the varying number of assessments, offspring gender, and number of siblings in the family using the obtained coefficients from the logistic regression performed (SPSS version 14).

Table 3.

Adjusted Odds Ratios for Developing an Internalizing, Externalizing or Any Diagnosis in Childhood for Offspring Evaluated Between the Ages of 8 and 11 (N=217).

| Absence of Internalizing Diagnosis | Presence of Internalizing Diagnosis | Odds Ratio* | 95% CFI | q-value | Absence of Externalizing Diagnosis | Presence of Externalizing Diagnosis | Odds Ratio* | 95% CFI | q-value | Absence of Any Diagnosis | Presence of Any Diagnosis | Odds Ratio* | 95% CFI | q-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Risk | 77 | 16 | 86 | 7 | 72 | 21 | |||||||||

| (N = 93) | 82.8% | 17.2% | 92.5% | 7.5% | 77.4% | 22.6% | |||||||||

| High Risk | 100 | 24 | 1.18 | 0.58–2.42 | 0.978 | 99 | 25 | 6.12 | 2.15–17.42 | 0.024 | 81 | 43 | 2.23 | 1.16–4.28 | 0.096 |

| (N = 124) | 80.6% | 19.4% | 79.8% | 20.2% | 65.3% | 34.7% | |||||||||

| Neither Parent Alcoholic | 48 | 11 | 54 | 5 | 43 | 16 | |||||||||

| (N = 59) | 81.4% | 18.6% | 91.5% | 8.5% | 72.9% | 27.1% | |||||||||

| Either Parent Alcoholic | 83 | 18 | 1.02 | 1.43–2.41 | 0.987 | 79 | 22 | 4.20 | 1.21–14.59 | 0.115 | 66 | 35 | 1.44 | 0.66–3.15 | 0.614 |

| (N = 101) | 82.2% | 17.8% | 78.2% | 21.8% | 65.3% | 34.7% | |||||||||

| Mother Not Alcoholic | 104 | 20 | 112 | 12 | 95 | 29 | |||||||||

| (N = 124) | 83.9% | 16.1% | 90.3% | 9.7% | 76.6% | 23.4% | |||||||||

| Mother Alcoholic | 47 | 13 | 1.99 | 0.82–4.84 | 0.312 | 43 | 17 | 4.23 | 1.64–10.83 | 0.024 | 34 | 26 | 3.43 | 1.58–7.46 | 0.024 |

| (N = 60) | 78.3% | 21.7% | 71.7% | 28.3% | 56.7% | 43.3% | |||||||||

| Father Not Alcoholic | 67 | 14 | 76 | 5 | 62 | 19 | |||||||||

| (N = 81) | 82.7% | 17.3% | 93.8% | 6.2% | 76.5% | 23.5% | |||||||||

| Father Alcoholic | 32 | 5 | 0.53 | 0.16–1.77 | 0.117 | 32 | 5 | 5.39 | 1.05–27.67 | 0.129 | 28 | 9 | 1.07 | 0.40–2.85 | 0.987 |

| (N = 37) | 86.5% | 13.5% | 86.5% | 13.5% | 75.7% | 24.3% | |||||||||

| Neither Parent Depressed | 57 | 10 | 61 | 6 | 51 | 16 | |||||||||

| (N = 67) | 85.1 % | 14.9% | 91.0% | 9.0% | 76.1% | 23.9% | |||||||||

| Either Parent Depressed | 38 | 12 | 1.80 | 0.69–4.69 | 0.508 | 44 | 6 | 1.20 | 0.34–4.26 | 0.987 | 36 | 14 | 1.16 | 0.48–2.82 | 0.987 |

| (N = 50) | 76.0% | 24.0% | 88.0% | 12.0% | 72.0% | 28.0% | |||||||||

| Mother Not Depressed | 129 | 23 | 128 | 24 | 109 | 43 | |||||||||

| (N = 152) | 84.9% | 15.1% | 84.2% | 15.8% | 71.7% | 28.3% | |||||||||

| Mother Depressed | 24 | 10 | 2.33 | 0.95–5.67 | 0.168 | 29 | 5 | 1.01 | 0.34–3.04 | 0.987 | 22 | 12 | 1.48 | 0.65–3.38 | 0.614 |

| (N = 34) | 70.6% | 29.4% | 85.3% | 14.7% | 64.7% | 35.3% | |||||||||

| Father Not Depressed | 87 | 16 | 95 | 8 | 79 | 24 | |||||||||

| (N = 103) | 84.5% | 15.5% | 92.2% | 7.8% | 76.7% | 23.3% | |||||||||

| Father Depressed | 12 | 2 | 0.95 | 0.19–4.88 | 0.987 | 13 | 1 | 0.88 | 0.09–8.47 | 0.987 | 12 | 2 | 0.45 | 0.09–2.25 | 0.614 |

| (N = 14) | 85.7% | 14.3% | 92.9% | 7.1% | 85.7% | 14.3% | |||||||||

| Neither Parent | 63 | 12 | 69 | 6 | 57 | 18 | |||||||||

| Drug Dependent | 84.0% | 16.0% | 92.0% | 8.0% | 76.0% | 24.0% | |||||||||

| (N = 75) | |||||||||||||||

| Either Parent | 43 | 7 | 1.05 | 0.35–3.13 | 0.987 | 36 | 14 | 3.75 | 1.12–12.58 | 0.117 | 34 | 16 | 1.30 | 0.53–3.21 | 0.915 |

| Drug Dependent | 86.0% | 14.0% | 72.0% | 28.0% | 68.0% | 32.0% | |||||||||

| ( N = 50) | |||||||||||||||

Odds ratios were adjusted for the linear effects of gender, the number of repeated assessments and for sibling participation in the study.

Table 4.

Adjusted Odds Ratios for Developing an Internalizing, Externalizing or Any Diagnosis in Adolescence for Offspring Evaluated Between the Ages of 12 and 18 (N=338).

| Absence of Internalizing Diagnosis | Presence of Internalizing Diagnosis | Odds Ratio* | 95% CFI | q-value | Absence of Externalizing Diagnosis | Presence of Externalizing Diagnosis | Odds Ratio* | 95% CFI | q-value | Absence of Any Diagnosis | Presence of Any Diagnosis | Odds Ratio* | 95% CFI | q-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Risk | 130 | 26 | 132 | 24 | 112 | 44 | |||||||||

| (N = 156) | 83.3% | 16.7% | 84.6% | 15.4% | 71.8% | 28.2% | |||||||||

| High Risk | 130 | 52 | 1.91 | 1.11–3.29 | 0.043 | 102 | 80 | 4.85 | 2.80–8.40 | <0.001 | 77 | 105 | 3.64 | 2.27–5.85 | <0.001 |

| (N = 182) | 71.4% | 28.6% | 56.0% | 44.0% | 42.3% | 57.7% | |||||||||

| Neither Parent Alcoholic | 84 | 12 | 80 | 16 | 71 | 25 | |||||||||

| (N = 96) | 87.5% | 12.5% | 83.3% | 16.7% | 74.0% | 26.0% | |||||||||

| Either Parent Alcoholism | 104 | 43 | 3.14 | 1.53–6.48 | 0.005 | 82 | 65 | 4.52 | 2.36–8.68 | <0.001 | 61 | 86 | 4.74 | 2.62–8.57 | <0.001 |

| (N = 147) | 70.7% | 29.3% | 55.8% | 44.2% | 41.5% | 58.5% | |||||||||

| Mother Not Alcoholic | 161 | 40 | 155 | 46 | 128 | 73 | |||||||||

| (N = 201) | 80.1% | 19.9% | 77.1% | 22.9% | 63.7% | 36.3% | |||||||||

| Mother Alcoholic | 60 | 22 | 1.89 | 0.98–3.66 | 0.079 | 41 | 41 | 5.34 | 2.82–10.09 | <0.001 | 33 | 49 | 3.97 | 2.19–7.20 | <0.001 |

| (N = 82) | 73.2% | 26.8% | 50.0% | 50.0% | 40.2% | 59.8% | |||||||||

| Father Not Alcoholic | 112 | 20 | 110 | 22 | 96 | 36 | |||||||||

| (N = 132) | 84.8% | 15.2% | 83.3% | 16.7% | 72.7% | 27.3% | |||||||||

| Father Alcoholic | 37 | 17 | 2.24 | 0.99–5.04 | 0.079 | 34 | 20 | 2.37 | 1.11–5.09 | 0.052 | 24 | 30 | 2.63 | 1.30–5.29 | 0.017 |

| (N = 54) | 68.5% | 31.5% | 63.0% | 37.0% | 44.4% | 55.6% | |||||||||

| Neither Parent Depressed | 88 | 20 | 85 | 23 | 68 | 40 | |||||||||

| ( N = 108) | 81.5% | 18.5% | 78.7% | 21.3% | 63.0% | 37.0% | |||||||||

| Either Parent Depressed | 72 | 27 | 1.95 | 0.98–3.87 | 0.079 | 68 | 31 | 1.89 | 0.99–3.63 | 0.079 | 55 | 44 | 1.57 | 0.88–2.81 | 0.164 |

| (N = 99) | 72.7% | 27.3% | 68.7% | 31.3% | 55.6% | 44.4% | |||||||||

| Mother Not Depressed | 178 | 45 | 154 | 69 | 127 | 96 | |||||||||

| (N = 223) | 79.8% | 20.2% | 69.1% | 30.9% | 57.0% | 43.0% | |||||||||

| Mother Depressed | 46 | 21 | 1.87 | 1.00–3.48 | 0.079 | 45 | 22 | 1.07 | 0.59–1.94 | 0.814 | 34 | 33 | 1.26 | 0.72–2.19 | 0.478 |

| (N = 67) | 68.7% | 31.3% | 67.2% | 32.8% | 50.7% | 49.3% | |||||||||

| Father Not Depressed | 129 | 34 | 125 | 38 | 101 | 62 | |||||||||

| (N = 163) | 79.1% | 20.9% | 76.7% | 23.3% | 62.0% | 38.0% | |||||||||

| Father Depressed | 22 | 6 | 1.41 | 0.50–3.97 | 0.544 | 19 | 9 | 1.86 | 0.75–4.69 | 0.215 | 17 | 11 | 1.36 | 0.57–3.23 | 0.531 |

| (N = 28) | 78.6% | 21.4% | 67.9% | 32.1% | 60.7% | 39.3% | |||||||||

| Neither Parent | 106 | 23 | 102 | 27 | 87 | 42 | |||||||||

| Drug Dependence | 82.2% | 17.8% | 79.1% | 20.9% | 67.4% | 32.6% | |||||||||

| (N = 129) | |||||||||||||||

| Either Parent | 50 | 20 | 2.23 | 1.05–4.71 | 0.068 | 36 | 34 | 4.17 | 2.08–8.34 | <0.001 | 26 | 44 | 4.70 | 2.36–9.36 | <0.001 |

| Drug Dependence | 71.4% | 28.6% | 51.4% | 48.6% | 37.1% | 62.9% | |||||||||

| (N =70) | |||||||||||||||

Odds ratios were adjusted for the linear effects of gender, the number of repeated assessments and for sibling participation in the study.

To evaluate the effects of parental psychopathology or risk group status on offspring outcome, K-SADS diagnoses were analyzed by grouping diagnoses into internalizing or externalizing groups and by presence of “any” diagnosis (Table 3 and Table 4). Grouping allowed for sufficient power to adequately test the models. The internalizing disorder group included mood (MDD, mania), anxiety (Generalized Anxiety Disorder [GAD], Panic Disorder [PD], Phobias, Overanxious Disorder [OAD], Separation Anxiety [SA]), and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder [OCD] . Externalizing disorders included CD, ADHD, ODD, and Alcohol Abuse, Alcohol Dependence, Drug Abuse, and Drug Dependence.

Because of the large number of comparisons required to evaluate parental and risk group effects (Table 3 and Table 4), an adjustment for false discovery rate (FDR) was performed for these comparisons. This approach, originally proposed by Benjamini and Hochberg (1995), treats the p-values as ordered statistics (using ranks) and computes corresponding q-values which are then directly compared to the FDR chosen. The most conservative option was chosen.

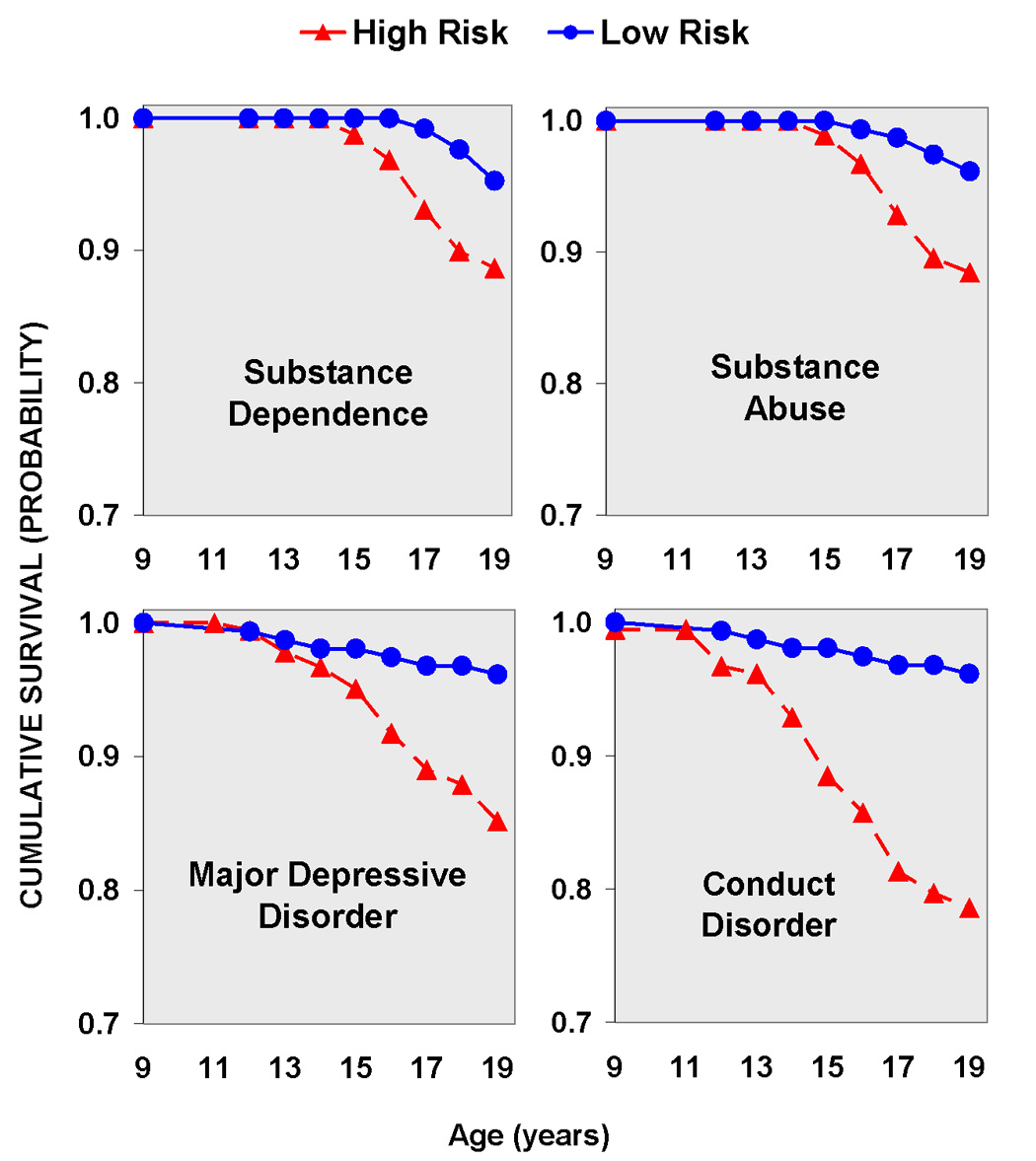

The third goal was to provide rates of individual diagnoses by risk group, for each developmental period (childhood [8–11] and adolescence [12–18]) (See Table 5). Our fourth goal was to examine the age of onset of disorders in association with risk group. Because the participants entered the study at varying ages and the age at most recent follow-up varied, Kaplan-Meier models were used allowing for censoring the data (Figure 1). Data were collected annually through age 19 allowing for determination of onset to within one year.

Table 5.

Relative Risks (Odds Ratios) of Children Having a DSM-III Diagnosis With the Specified Independent Variable

| Childhood (Ages 8–11) | Adolescence (Ages 12–18) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=217) | (N=338) | |||||||||

| Diagnoses | LR (N=93) | HR (N=124) | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p Value | LR (N=156) | HR (N=182) | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p Value |

| Depression | 1 | 4 | NS | 6 | 27 | 4.40 a | (1.72 – 11.26) | 0.002 | ||

| Mania | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||||||

| Bulimia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||||||

| Panic Attacks | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | NS | |||||

| Separation Anxiety | 6 | 8 | 0.94 | (0.30 –2.88) | NS | 3 | 1 | NS | ||

| Phobia | 12 | 17 | 1.05 | (0.46 –2.37) | NS | 22 | 29 | 1.14 | NS | |

| OCD | 1 | 2 | NS | 1 | 4 | NS | ||||

| Generalized Anxiety | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | NS | |||||

| Conduct Disorder | 0 | 5 | 6 | 39 | 7.42 | (2.98 – 18.43) | < 0.001 | |||

| Psychosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||||||

| Attention Deficit Disorder | 7 | 21 | 4.28 | (1.53 – 11.94) | 0.006 | 8 | 24 | 4.25 | (1.72 – 10.51) | 0.002 |

| Oppositional Disorder | 2 | 15 | 21.09 | (3.48 – 127.98) | 0.001 | 11 | 50 | 6.13 | (2.95 – 12.76) | < 0.001 |

| Alcohol Abuse | 0 | 0 | 6 | 16 | 1.92 | NS | ||||

| Drug Abuse | 0 | 0 | 3 | 14 | 4.43 | (1.21 – 16.20) | 0.024 | |||

| Alcohol Dependence | 0 | 0 | 10 | 13 | 0.78 | NS | ||||

| Drug Dependence | 0 | 0 | 2 | 18 | 13.64 | (2.85 – 65.15) | 0.001 | |||

| Either Alcohol or Drug Abuse | 6 | 26 | 3.73 | (1.47–9.44) | 0.005 | |||||

| Either Alcohol or Drug Dependence | 10 | 27 | 2.50 | (1.10–5.65) | 0.028 | |||||

Odds ratios were adjusted for gender, other siblings in the analysis, and the number of evaluations performed during each developmental period (ages 7–11 or 12–18).

Figure 1.

Upper Left Panel: Cumulative survival for substance dependence (either alcohol or drug dependence) by risk group status. Note the earlier onset of dependence in the high risk group.

Upper Right Panel: Cumulative survival for substance abuse (alcohol or drug abuse) by risk group status. Note the earlier onset of dependence in the high risk group.

Upper Left Panel: Cumulative survival for major depressive disorder by risk group status. It is widely known that high risk offspring are at greater risk for externalizing disorders of childhood and adolescence. These findings illustrate that offspring from multiplex for AD families are also at increased risk for depression.

Lower Right Panel: Cumulative survival for Conduct Disorder by risk group status. Note that over 20% of the high risk group meet criteria for conduct disorder by age 19.

3. Results

3.1. Socioeconomic Status and Minority Membership

Statistically significant differences in SES were not seen between the two studies justifying the merging of the data from each of them, though minor risk group differences within studies were seen. For CPFFS participants SES values were: HR = 38.2 ± 10.6 and LR = 44.2 ± 11.76, adjacent Hollingshead strata. For the BRFFS study: HR = 36.2 ± 12.6 and LR = 45.9 ± 11.7. The overall minority rate in our series of families is 13%.

3.2. Risk Status, Parental Psychopathology, and Childhood Disorders (Ages 8–11)

Multiplex familial high risk status increased the odds that 8–11 year old children would have an externalizing disorder (odds ratio = 6.12, q =0.024). The likelihood that offspring would experience some form of psychopathology before the age of 12 was elevated in association with maternal alcoholism (odds ratio = 3.43, q = 0.024). These children of AD mothers showed an increased risk for externalizing disorders (odds ratio = 4.23, q = 0 .024) that was not seen in offspring of alcohol dependent fathers (Table 3). Interestingly, parental drug dependence or depression (neither or either parent affected) did not appear to increase risk for externalizing or internalizing psychopathology in childhood. When analyzed separately by parent, mother or father, none of the comparisons were significant for presence of an internalizing disorder in young children.

3.3. Risk Status, Parental Psychopathology and Adolescent Disorders (Ages 12–18)

In comparison to controls, adolescents with multiplex familial risk for developing alcohol dependence had a 3.6-fold higher odds of experiencing a psychiatric disorder in adolescence (q < 0 .001), (See Table 4) with elevations for both internalizing (odds ratio =1.91, q = 0.043) and externalizing disorders (odds ratio = 4.85, q <0 .001).

The odds of having “any” diagnosis in adolescence was higher for adolescents whose mothers were alcohol dependent compared to those without AD (odds ratio = 3.97, q < 0 .001), as it was for externalizing disorders (odds ratio = 5.34, q < 0 .001)(Table 4). Having an AD father also increased the odds that adolescents would experience one or more psychiatric disorders (odds ratio = 2.63, q = 0.017) including having an externalizing disorder (odds ratio = 2.37, q = 0 .052). Overall, similar results were seen whether the parent who was alcohol dependent was the mother or the father, or whether the familial risk dimension was used as a predictor.

Parental drug dependence was associated with increased odds that the adolescent would have an externalizing disorder (odds ratio = 4.17, q < 0.001). The presence of a depressive disorder in the mother, but not the father increased the risk that the adolescent offspring would have an internalizing disorder (odds ratio = 1.87, q = 0.079) though this was only a trend (See Table 4).

3.4. Relative Risks for Specific Diagnoses in Childhood and Adolescence

In order to have sufficient power to test the effects of familial/genetic risk and parental diagnoses, individual diagnoses were collapsed into broader categories of internalizing and externalizing psychopathology or “any” psychopathology. In order to place the present results in context of other findings, this section characterizes the increased risk associated with familial background and specific disorders.

During childhood, offspring from high-risk families were significantly more likely to receive a diagnosis of ADHD (P = 0.006) and ODD (P = 0.001) than were low-risk controls (Table 5). During adolescence ADHD (P = 0.002), ODD (P < 0.001), Conduct Disorder (P < 0.001), Drug Abuse (P = 0.024) and Drug Dependence (P = 0.001) were elevated in association with being a member of a multiplex family. Significant risk group differences were also seen for Major Depressive Disorder (P = 0.002) (Table 5).

Kaplan-Meier survival models were used to determine the age of onset for Conduct Disorder, Drug or Alcohol Abuse, Drug or Alcohol Dependence and Major Depressive Disorder using familial risk status as an explanatory variable and tested with a Tarone-Ware statistic (see Figure 1). Survival time was significantly shorter for high risk offspring with “loss of survival” beginning to occur at about age 12. For major depressive disorder, χ2 = 9.12, df =1, P = 0.003; for Drug or Alcohol Abuse, χ2 = 9.98, df =1, P = 0.002; for Alcohol or Drug Dependence χ2 = 5.79, df =1, P = 0.016; and for Conduct Disorder χ2 = 20.12, df =1, P < 0.001. These results indicate that high risk offspring not only have greater incidence of these disorders as shown in Table 5, but also have an earlier onset as well.

3.5. Combined Model

The influence of familial risk, parental alcohol or drug dependence and parental depression was evaluated in separate models due to missing data considerations. Specifically, all of the offspring could be classified by risk status of the pedigree from which they were drawn. Parental alcohol or drug dependence was not always possible to determine. Some of the probands did not know the whereabouts of the co-parent of the child. Analysis of all variables in one hierarchical model would have been more parsimonious but would suffer from problems associated with missing data for the parental diagnostic classification in some cases.

A combined model was used to evaluate the effects of risk status, parental alcohol or drug dependence, and parental depression on adolescent outcome (MDD and AD). Comparisons were made adjusting for number of siblings and the number of repeated measures. For the presence of MDD in adolescence, presence of parental alcohol or drug dependence, depression, and familial risk status were entered into the model to determine the significance of each of the variables to the model. This analysis revealed that MDD in adolescent offspring showed a significant association for only the case where either parent was alcohol dependent (Wald = 6.50, df =1, P = 0.011). The same parental variables when entered for adolescent AD outcome by age 18 showed a significant association with having either parent alcohol dependent (Wald = 7.07, df = 1, P = 0.008). Having either parent drug dependent or depressed did not elevate adolescent AD when tested within this model. When adolescent AD was tested in a model that simultaneously evaluated parental AD and multiplex risk status, only membership in a multiplex family showed a trend indicating an association (Wald = 3.66, df = 1, p=0.056). However, when either alcohol or drug dependence in adolescence was considered as the outcome variable, only parental alcohol dependence was associated with increased risk (Wald = 7.82, df =1, p=0.005); familial risk was not.

3.6. Risk Status, Change and Persistence of Disorders from Childhood to Adolescence

To specifically examine the pattern of change from childhood to adolescence in relation to risk group status, the offspring were divided into four groups: those with no diagnosis in either period, those with a diagnosis only in childhood, those with a diagnosis in adolescence only, and those with a diagnosis in both periods. Of the 55 low-risk children who were without a diagnosis during childhood only 13 cases or (23.6%) developed a disorder during adolescence. In contrast, of the 72 high-risk children who were free of all diagnoses during the multiple times they were evaluated in childhood, 35 cases or (48.6 %) had a diagnosis during the adolescent follow up. The odds of developing a diagnosis during adolescence in offspring who had previously been free of diagnosable illness in childhood was significantly higher for high-risk children than that for low-risk children (odds ratio = 3.06, P = 0.005). Also, for those children who had a diagnosis in childhood, a greater proportion of high-risk (78.1%) compared to low-risk (55.6%) children reported persistence of that disorder into adolescence, though the proportion was not statistically significant.

4. Discussion

4.1 Confirmation and Extension of Previous Findings

The offspring from these families with multiple cases of alcohol dependence were found to be at increased risk for several psychiatric disorders (ADHD, CD, ODD, MDD, and Drug Abuse/Dependence), especially Conduct Disorder (21.4%) and MDD (14.8 %). The present results confirm previous studies (Earls et al., 1988; Hussong et al., 1988; Reich et al., 1993; Hill and Muka, 1996; Hill et al., 1999a; Kuperman et al., 1999; Merikangas and Avenoli, 2000; Hill et al., 2000; Ohanessian et al., 2004) showing that high-risk offspring of alcoholic parents are at elevated risk for CD, ODD, ADHD, and substance use disorders, or externalizing disorders. However, the present results show higher rates than those reported in other studies (Hussong et al., 1988; Merikangas et al., 1998; Kuperman et al., 1999; Clark et al., 2004). As one comparison, a Pittsburgh sample (Clark et al., 2004) of unselected offspring of substance use disorder parents found rates of 2.4% for CD and 2.3% for MDD. The most obvious difference in the two samples is the greater familial/genetic loading for alcohol dependence in our multiplex families.

Multiplex ascertainment appears to lead to increased segregation of susceptibility genes and their intermediate phenotypes (Smalley et al., 2000). A clustering of childhood traits (ADHD, CD, and ODD) appear to be associated with adult alcohol dependence in unselected samples (Earls et al., 1988; Reich et al., 1993; Merikangas and Avenevoli, 2000; Clark et al., 2004) and in samples derived from multiplex ascertainment (Kuperman et al., 1999; Ohannessian et al., 2004).

4.2 New Findings

A significant elevation in depressive disorders (MDD) during adolescence was seen in association with risk status. Because some of the adolescents did not have a parent with AD but did come from multiplex pedigrees in which four first and second degree relatives had been diagnosed with alcohol dependence, elevation of MDD seen in these adolescents points to familial transmission that goes beyond the presence of an alcohol dependent parent.

The impact of parental depression on offspring differed by developmental period with minimal impact seen in younger children (8 and 11 years) while maternal depression occurring when the offspring were adolescents did appear to influence the likelihood that the offspring would experience an internalizing disorder, though the effect was not significant. Similarly, parental drug dependence when offspring were children did not elevate the offspring’s risk for psychopathology, but during adolescence the risk for developing externalizing disorders or “any disorder” was greatly elevated in association with parental drug dependence.

The design of the study allowed for comparison of parental alcohol dependence (AD) with risk status (multiplex alcohol dependence or control). Participant offspring had been identified through families containing two adult same-sex alcoholic siblings. Some offspring from high risk families did not have alcoholic parents though they had multiple aunts, uncles or grandparents with alcoholism. Results obtained using presence or absence of multiplex familial risk status are largely consistent with those obtained when analyses are performed using the presence or absence of parental alcoholism. In other words, youngsters from multiplex pedigrees have elevated risk for a number of disorders even if they do not have an AD parent.

Although the elevated risk seen in offspring of alcoholics has often been attributed to the alcoholism diagnosis of the parent, it is clear that significant comorbidity would be expected in these parents. Helzer and Pryzbeck (1985) have shown that alcoholic individuals drawn from community samples have increased odds for having other psychiatric disorders. The present longitudinal studies were designed to reduce comorbidity in the parents of these offspring through selection of only those families where the proband had an alcoholism diagnosis before becoming drug dependent or before developing MDD, so that any comorbidity was secondary. Nevertheless, some comorbidity remains using this selection strategy and this comorbidity appears to influence outcome of offspring.

A comment is needed regarding the significant elevation in drug abuse and dependence but not alcohol abuse or dependence in these offspring selected for multiplex alcohol dependence. Greater availability of drugs in the offspring generation may have increased the likelihood that this generation would become dependent on drugs. Also, as these offspring move through young adulthood patterns of use it may be expected that patterns are likely to change with increased consumption of alcohol and decreased use of street drugs. Long term follow-up is ongoing to determine the type and pattern of alcohol and drug exposure and consequent dependence.

4.3. Limitations and advances of the study

In spite of the valuable data set that our two family studies offer, some possible limitations must be mentioned. In order to have a sufficiently large number of cases to evaluate the odds ratios for any particular disorder, analyses were based on the presence of a disorder at any time during the developmental period examined. Although steps were taken to adjust for this variation, children evaluated a larger number of times would have more opportunity to exhibit the disorder than those with fewer evaluations. Alternatively, this may be viewed as an opportunity to increase the reliability of assessment. While future publications will address the stability of diagnosis across waves using latent growth models, the purpose of the present analyses were to address the issue of familial/genetic loading and parental diagnosis on outcome of offspring during the child and adolescent periods.

The two proband selection criteria used in the present study oversamples families at the extreme end of the distribution of AD families, possibly limiting the generalizability of findings obtained. Obviously, the next step will be to test similar hypotheses concerning the effects of parental diagnosis on offspring using community samples that are not highly selected for parental subtypes.

The present results provide several suggestions for prevention and treatment of substance use disorders and offer new questions for future research. First, it appears that offspring of alcoholic parents are more vulnerable to developing a psychiatric disorder during adolescence than in childhood. Multiple assessments of high and low-risk children and adolescents has revealed that children who are free of illness in childhood are relatively more likely to be free of psychiatric illness in adolescence though a significantly greater number of high-risk children without a disorder in childhood developed a new diagnosis during adolescence than did controls. It also appears that absence of a childhood diagnosis predicts an absence of a diagnosis in adolescence for control children much better than it does for high risk offspring. Adolescence appears to be an especially vulnerable period for youngsters with familial/genetic background suggestive of greater alcohol use disorder susceptibility. Nevertheless, 22% of high-risk children were free of illness during adolescence. These offspring are especially interesting because of their resiliency. We have previously noted that offspring of alcohol dependent mothers are more likely to escape diagnosable problems if the co-parent is without alcohol or drug dependency (Hill and Muka, 1996). However, other factors contributed to improved resiliency may be present that are yet to be identified.

A comment is needed regarding the relatively high rate of ASPD (34%) in mothers with AD. These mothers came from the BRFFS study and were members of a proband pair of alcohol dependent sisters. Because ascertainment through two AD sisters can be expected to increase the disease susceptibility within these families, comborbid conditions can be expected to be increased as well. Alcohol dependent women show elevated rates of ASPD relative to women without AD (Helzer et al., 1985). Because the offspring were at increased liability for disorders in their parents, it may be expected that the offspring were frequently diagnosed with CD.

Although it is well-known that CD of youth and ASPD in adulthood are concomitants of alcohol and drug dependence, we would be remiss in focusing only on externalizing disorders in high-risk offspring. The adolescents in the present study were 4.4 times more likely to suffer from a depressive disorder than their low-risk cohorts. This suggests the need to identify these problems in vulnerable youth with an eye toward prevention of more serious problems including suicide.

The present studies are ongoing and include a young-adult component that will track the offspring into one of the most vulnerable periods for emergence of substance abuse disorders and allow for determining the impact of child and adolescent disorders on the emergence of psychiatric disorders in young adulthood.

Acknowledgements

Supported by grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism AA 005909, AA 008082, AA 015168

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 1995;Series B 57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Cadoret RJ, Yates WR, Troughton E, Woodworth G, Stewart MA. An adoption study of drug abuse/dependency in females. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1996;37:88–94. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(96)90567-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers WJ, Puig-Antich J, Hirsch M, Paez P, Ambrosini PJ, Tabrizi MA, Davies M. The assessment of affective disorders in children and adolescents by semistructured interview: Test-retest reliability of the schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-aged children, present episode version. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1985;42:696–702. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790300064008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, Cornelius J, Wood DS, Vanyukov M. Psychopathology risk transmission in children of parents with substance use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:685–691. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croughan JL. Studying Drug Abuse. In: Robins LN, editor. The contributions of family studies to understanding drug abuse. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1985. pp. 93–116. [Google Scholar]

- Earls F, Reich W, Jung KG, Cloninger CR. Psychopathology in children of alcoholic and antisocial parents. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1988;12:481–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1988.tb00230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin DW, Schulsinger F, Hermansen L, Guze SB, Winokur G. Alcohol problems in adoptees raised apart from alcoholic biological parents. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1973;28:238–243. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1973.01750320068011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunzerath L, Goldman D. G X E: A NIAAA workshop on gene-environment interactions. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 2003;27(3):540–562. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000057944.57330.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurling HM, Grant S, Dangl J. The genetic and cultural transmission of alcohol use, alcoholism, cigarette smoking and coffee drinking: a review and an example using a log linear cultural transmission model. British Journal of Addiction. 1985;80:269–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1985.tb02540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helzer JE, Pryzbeck TR. The co-occurrence of alcoholism with other psychiatric disorders in the general population and its impact on treatment. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1985;49:219–224. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1988.49.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill SY, Cloninger CR, Ayre FR. Independent familial transmission of alcoholism and opiate abuse. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 1977;1:335–342. [Google Scholar]

- Hill SY, Muka D. Childhood psychopathology in children from families of alcoholic female probands. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35:725–733. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199606000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill SY, Locke J, Lowers L, Connolly J. Psychopathology and achievement in children at high-risk for developing alcoholism. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999a;38:883–891. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199907000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill SY, Shen S, Locke J, Steinhauer SR, Konicky C, Lowers L, Connolly J. Developmental delay in P300 production in children at high risk for developing alcohol-related disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 1999b;46:970–981. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill SY, Shen S, Lowers L, Locke J. Factors predicting the onset of adolescent drinking in families at high risk for developing alcoholism. Biological Psychiatry. 2000;48:265–275. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00841-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill SY, Shen S, Zezza N, Hoffman EK, Perlin M, Allan W. A genome wide search for alcoholism susceptibility genes. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B (Neuropsychiatric Genetics) 2004;128B:102–113. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four Factor Index of Social Status. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Curran PJ, Chassin L. Pathways of risk for accelerated heavy alcohol use among adolescent children of alcoholic parents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1988;26:453–466. doi: 10.1023/a:1022699701996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Karlowski LM, Neale MC, Prescott CA. Illicit psychoactive substance use, heavy use, abuse, and dependence in a US population-based sample of male twins. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57:261–269. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.3.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuperman S, Schlosser SS, Lidral J, Reich W. Relationship of child psychopathology to parental alcoholism and antisocial personality disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:686–692. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199906000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Stevens DE, Fenton B, Stolar M, O' Malley S, Woods SW, Risch N. Comorbidity and familial aggregation of alcoholism and anxiety disorders. Psychological Medicine. 1998;28:773–788. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Avenevoli S. Implications of genetic epidemiology for the prevention of substance use disorders. Addictive Behavior. 2000;25:807–820. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton NE, Mi MP. Multiplex families with two or more probands. American Journal of Human Genetics. 1968;20:361–370. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohannessian CM, Hesselbrock VM, Kramer J, Kuperman S, Bucholz KK, Schuckit MA, Nurnberger JI. The relationship between parental alcoholism and adolescent psychopathology: A systematic examination of parental comorbid psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:519–533. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000037781.49155.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich W, Earls F, Frankel O, Shayka JJ. Psychopathology in children of alcoholics. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32:995–1002. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199309000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, Ratcliff KS. National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule: Its history, characteristics and validity. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1981;38:381–389. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780290015001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidman LJ, Faraone SV, Goldstein JM, Kremen WS, Horton NJ, Makris N, Toomey R, Kennedy D, Caviness VS, Tsuang MT. Left hippocampal volume as a vulnerability indicator for schizophrenia: a magnetic resonance imaging morphometric study of nonpsychotic first-degree relatives. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:839–849. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.9.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smalley SL, McGough JJ, Del’Homme M, NewDelman J, Gordon E, Kim T, Liu A, McCracken JT. Familial clustering of symptoms and disruptive behaviors in multiplex families with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:1135–1143. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200009000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuang MT, Lyons MJ, Meyer JM, Doyle T, Eisen SA, Goldberg J, True W, Lin N, Toomey R, Eaves L. Co-occurrence of abuse of different drugs in men: The role of drug-specific and shared vulnerabilities. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:967–972. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.11.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]