Abstract

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) are nuclear receptors (NRs) that regulate genes involved in lipid and glucose metabolism. PPAR activity is regulated by interactions with cofactors and of interest are cofactors with ubiquitin ligase activity. The E6-associated protein (E6-AP) is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that affects the activity of other NRs, although its effects on PPARs have not been examined. E6-AP inhibited the ligand-independent transcriptional activity of PPARα and PPARβ, with marginal effects on PPARγ, and decreased basal mRNA levels of PPARα target genes. Inhibition of PPARα activity required the ubiquitin ligase function of E6-AP, but occurred in a proteasome-independent manner. PPARα interacted with E6-AP, and in mice treated with PPARα agonist clofibrate, mRNA and protein levels of E6-AP were increased in wildtype, but not in PPARα null mice, indicating a PPARα-dependent regulation. These studies suggest coordinate regulation of E6-AP and PPARα, and contribute to our understanding of the role of PPARs in cellular metabolism.

1. INTRODUCTION

The peroxisome proliferator activated receptors (PPARs) are nuclear hormone receptors that regulate lipid and glucose metabolism, and are critical to the maintenance of cellular energy homeostasis. In addition, they regulate several biological processes such as inflammation, differentiation, apoptosis, and wound healing [1, 2]. Three different subtypes of PPARs mediate these responses: PPARα, PPARβ, and PPARγ. PPARα is activated by fatty acids, fatty acid metabolites, and peroxisome proliferators, a diverse group of xenobiotics that includes the fibrate hypolidemic drugs, phthalate esters, and herbicides [3]. Regulation of gene expression by PPARα follows the classical ligand-dependent transcription factor mechanism. Upon ligand binding, PPARα binds to PPAR-response elements (PPREs) in the promoter of target genes as a heterodimer with retinoid X receptor (RXR). The multiple protein-PPARα interactions that occur in the transcription complex are important for proper target gene regulation [4]. These proteins, often called coregulators, can increase (coactivators) or repress (corepressors) transcriptional activity. Some coregulators possess enzymatic activity such as histone acetyl transferase or histone deacetylase, and modulate chromatin structure to regulate gene transcription [5]. Several proteins with ubiquitin ligase activity have been characterized in the last few years as coregulators for nuclear receptors. The recruitment of ubiquitin-proteasome components to the promoters of nuclear receptor target genes suggest an additional layer of transcriptional regulation by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway [6–8].

This study examines regulation of PPARα by E6-associated protein (E6-AP), a protein linked to the Angelman syndrome and an E3 ubiquitin ligase that belongs to the HECT (homologous to the E6-AP C-terminus) family [9]. Ablation of E6-AP in mice is associated with steroid hormone resistance and reproductive defects [10]. E6-AP coactivates nuclear receptors such as the estrogen receptor (ER) and the progesterone receptor [11]. In addition, it mediates proteasomal degradation of proteins such as the nuclear receptor coactivator AIB1 [12], and tumor suppressors Rb (retinoblastoma protein), and p53 [13–15]. The studies presented here suggest a role for the ubiquitin ligase function of E6-AP in regulating PPARα activity.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Plasmids

The plasmids pBKRSV-E6AP, pBKRSV-E6AP-C833S, and pM-E6AP were a kind gift from Dr. Zafar Nawaz (Department of Cell Biology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Tex, USA). The construction of the pVP16-PPARα plasmid has been described previously [16]. The pFR-luciferase (UAS luciferase) plasmid was purchased from BD Biosciences Clontech (Palo Alto, Calif, USA), while pRL/TK and pRL/CMV were from Promega (Madison, Wis, USA). The peroxisome proliferator response element (PPRE) reporter pACO (-581/-471) G.Luc was supplied by Dr. Jonathan Tugwood (AstraZeneca Maccelsfield, UK) and has been described previously [17]. The pcDNA3.1/V5-His-PPARα plasmid has been described previously [16]. The pcDNA3.1/FLAG-PPARβ and pcDNA3.1-PPARγ plasmids were a kind gift from Dr. Curtis Omiecinski (Department of Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences, The Pennsylvania State University, Pa, USA).

2.2. Transfections and reporter assays

FaO cells (maintained in DMEM/Nutrient F-12 Ham with 8% serum and 100 units each of penicillin and streptomycin) were transfected using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif, USA), following manufacturer's instructions. Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) was used to transfect 293T cells (maintained in HG-DMEM with 8% serum and 100 units each of penicillin and streptomycin) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For reporter assays examining transient PPRE activity, all transfections included pRL/CMV (Promega) to control for transfection efficiency and ACO-luciferase. When indicated, following transfection, cells were treated with 0.1% DMSO or 5 μM MG132 for 6 hours. For reporter assays examining transient Gal4 response element activity, all transfections included pRL/CMV to control for transfection efficiency and pFR-Luciferase. In Gal4 response element assays, cells were treated for 6 hours with 0.1% DMSO or 50 μM Wy-14,643 before lysis. Cells were lysed and renilla and firefly luciferase activities were examined using the Dual Luciferase Assay kit (Promega). Luciferase activity was corrected for transfection efficiency (pRLTK/pRLCMV) and extraction yield (via total protein assay).

2.3. Real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated using Tri Reagent (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The total RNA was reverse transcribed using the ABI High Capacity cDNA Archive Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif, USA). Standard curves were made using serial dilutions from pooled cDNA samples. Real Time PCR was performed using the SYBR Green PCR Mater Mix (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's protocol and amplified on the ABI Prism 7300 Sequence Detection system. Messenger RNA levels of all genes were normalized to β-actin mRNA. Primer sequences (5′-3′) are E6-AP forward: gaaatgaggcctgcacgaat, E6-AP reverse: gaagaaaagttggacaggaagca, β-actin forward: ggctctatcctggcctcactg, β-actin reverse: cttgctgatccacatctgctg. Primers for Acyl CoA Oxidase (ACO) Cytochrome P450 IV A10 (CYP4A10), Angiopoietin-like protein 4 (Angplt4), have been described previously [16]. Sequences (5′-3′) for other genes measured are fatty acid binding protein 1 (FABP1) forward: ttctccggcaagtaccaagtg, FABP1 reverse: tcatgaagggctcaaagttctctt, Enoyl CoA Hydratase forward: cccgcaggatctttaacaagc, Enoyl CoA Hydratase reverse: cactgtccatgttgggcaag.

2.4. Western blotting

Mouse livers were homogenized in lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 8), 120 mM NaCl, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, and 1 : 100 dilution of protease-inhibitor cocktail (Sigma) after which particulates were removed by centrifugation. Liver lysates were subjected to SDS/PAGE. Proteins were transferred to Immobilon-PVDF membrane (Millipore), followed by western using anti-E6AP antibody (H-182, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Band intensities were quantitated using Optiquant Acquisition and Analysis Software.

2.5. Mice

8-week old-male wild-type, and PPARα-null mice [18] were housed in a light (12 hours light/12 hours dark) and temperature (25°C) controlled environment in microisolator cages. Mice were gavaged daily with either vehicle control (corn oil) or 500 mg clofibrate/kg body weight for 14 days. Mice were euthanized, livers weighed and homogenized, RNA or protein isolated for analysis as described above.

3. RESULTS

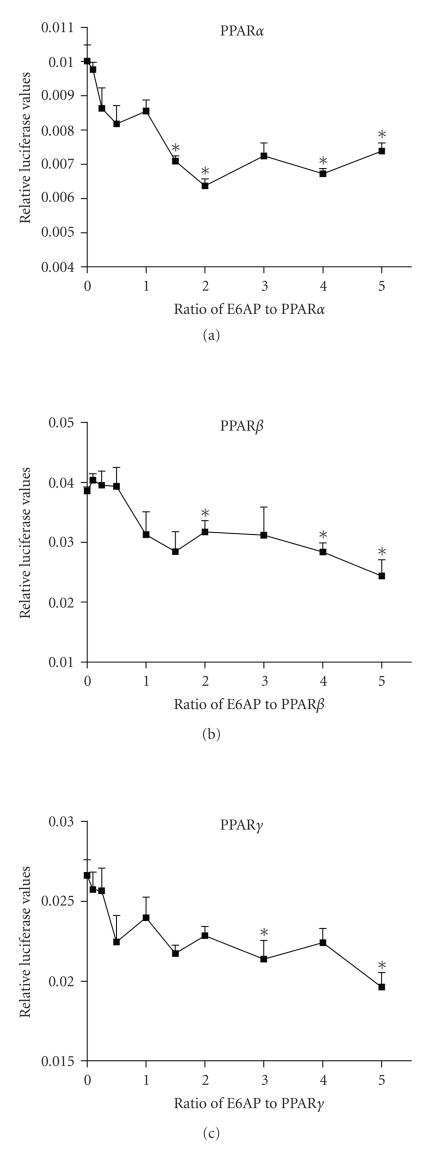

3.1. E6-AP inhibits the transcriptional activity of PPARα, PPARβ, and PPARγ

The transcriptional activity of PPARα, PPARβ/δ, and PPARγ isotypes was examined in the presence of E6-AP, by measuring the activity of a reporter gene under the control of a natural PPRE. As seen in Figure 1, transfecting increasing amounts of E6-AP inhibited PPAR transactivation in a dose-dependent manner for all three PPAR isotypes. A 40% decrease in transactivation was observed for PPARα and PPARβ, with a statistically significant decrease observed first at a ratio of 1.5 : 1 for E6-AP : PPARα, and 2 : 1 for E6-AP : PPARβ. A 30% decrease in transactivation was seen with PPARγ, with a statistically significant decrease observed first at a ratio of 3 : 1 for E6-AP : PPARγ. No changes were observed in ligand-induced activity of the receptors in the presence of E6-AP (data not shown).

Figure 1.

E6-AP inhibits the transcriptional activity of PPARα, PPARβ, and PPARγ. 293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing 4X-ACO-Luciferase, pRLCMV, PPARα, PPARβ or PPARγ, and E6-AP. Cells were lysed and luciferase activity was corrected for transfection efficiency and protein. Asterisks indicate a significant difference in luciferase values when compared to the 0 ratio group. (*P < .05 with statistical analysis using ANOVA). The graphs are representative of 3 independent experiments.

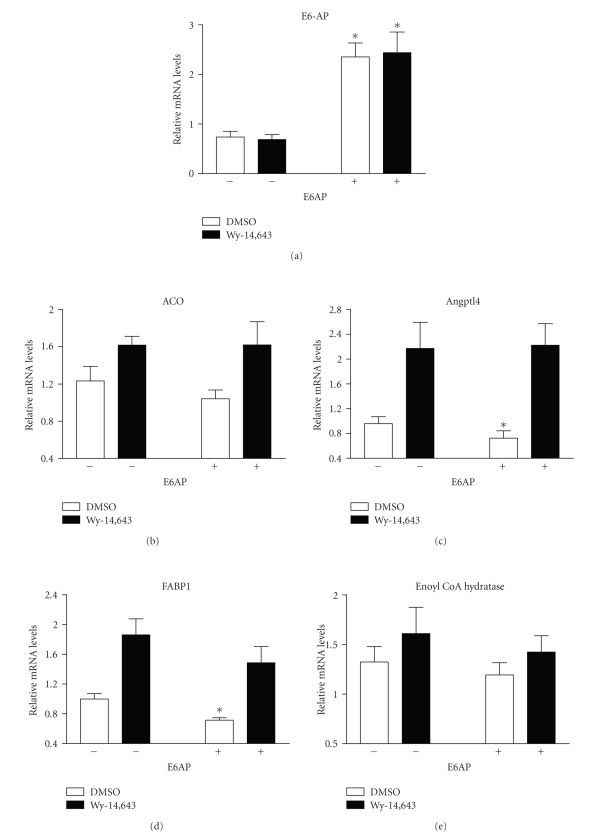

3.2. E6-AP overexpression affects PPARα target genes

To further examine the effect of E6-AP on the transcriptional activity of PPARα, E6-AP was expressed in FaO cells by transient transfection, followed by treatment with PPARα ligand Wy-14,643. The effect of E6-AP overexpression on mRNA levels of endogenous PPARα target genes was measured. The genes examined (angiopoietin-like protein 4 or Angplt4, fatty acid binding protein 1 or FABP1, acyl CoA oxidase or ACO and enoyl CoA hydratase) were chosen based on their role in PPARα-mediated lipid metabolism, or were previously identified in gene expression microarrays in FaO cells [19]. As seen in Figure 2, E6-AP expression resulted in statistically significant changes in mRNA levels Angplt4 (24% decrease) and FABP1 (28% decrease), in the absence of ligand. As previously seen with PPRE-driven reporter assays (Figure 1), no changes were seen in ligand-induced mRNA levels of PPARα target genes with E6AP expression.

Figure 2.

E6-AP expression results in decreased mRNA levels of PPARα target genes. FaO cells were transfected with empty vector or plasmid expressing E6-AP, followed by treatment with 0.1% DMSO or 50 μM Wy-14,643 for 6 hours. Total RNA was isolated from the cells and real-time PCR was performed on reverse transcribed RNA. Asterisks indicate a significant difference when compared to the corresponding control group. (*P < .05 with statistical analysis using ANOVA). The graphs represent mean values obtained from 2 independent experiments.

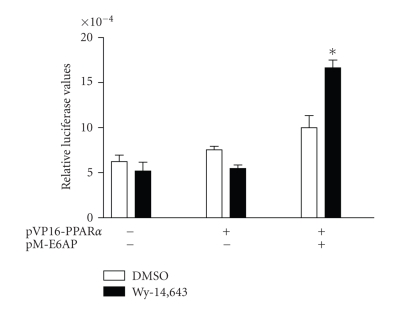

3.3. E6-AP interacts with PPARα

To examine if the effect of E6-AP on the transcriptional activity of PPARα was due to a direct interaction between the two proteins, mammalian-two-hybrid assays were performed using plasmids expressing PPARα fused to the pVP16 activation domain and E6-AP in the pM vector. The Gal4 response element reporter (pFR-luciferase) was used to assess the interaction between E6-AP and PPARα. As seen in Figure 3, induction with PPARα agonist Wy-14,643 was seen only when E6-AP was coexpressed with PPARα, indicating an interaction between the two proteins.

Figure 3.

E6-AP interacts with PPARα. 293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing pFR-Luciferase, pRLCMV, pVP16-PPARα, pM-E6-AP. Cells were lysed and luciferase activity was corrected for transfection efficiency and protein. Asterisks indicate a significant difference in Wy-14,643 induction when compared to the corresponding DMSO group. (*P < .05 with statistical analysis using ANOVA). The graph is representative of 2 independent experiments.

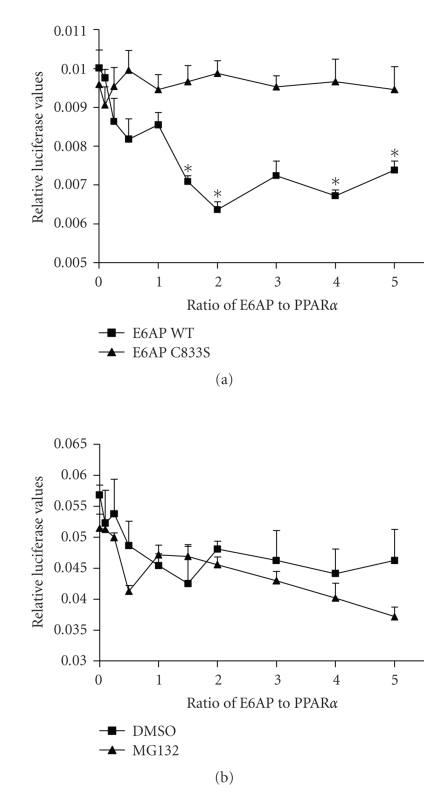

3.4. The E3 ubiquitin ligase function of E6-AP is required for inhibition of PPARα transcriptional activity

In order to determine if the effect of E6-AP on PPARα activity was mediated by the E3 ubiquitin ligase function of E6-AP, E6-AP C833S, a mutant defective in ubiquitin ligase function was used. Unlike the changes in reporter activity seen with wildtype (WT) E6-AP (Figure 1), transfecting increasing amounts of E6-AP-C833S did not result in any changes in activity (Figure 4(a)), indicating that the ubiquitin ligase function of E6-AP is required for regulating the transcriptional activity of PPARα. These differences were not due to different transfection efficiencies, since both E6-AP WT and E6-AP-C833S expressed equally well in these cells (data not shown). To further assess if E6-AP-mediated inhibition of PPARα transactivation was via proteasomal degradation, PPRE-dependent reporter assay was performed in the presence of proteasome inhibitor MG132. Transfecting increasing amounts of E6-AP resulted in decreased reporter activity in the presence and absence of MG132 (Figure 4(b)), indicating that E6-AP-mediated inhibition of PPARα transactivation occurs via a proteasome-independent mechanism.

Figure 4.

E3 ubiquitin ligase activity of E6-AP is required for regulating PPARα transactivation. (a) 293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing 4X-ACO-Luciferase, pRLCMV, PPARα, E6-AP, or E6-AP-C833S that is defective in ubiquitin ligase function. (b) Cells were treated with 0.1% DMSO or 5 μM MG132 for 6 hours. Cells were lysed and luciferase activity was corrected for transfection efficiency and protein. Asterisks indicate a significant difference when compared to the corresponding 0 ratio group. (*P < .05 with statistical analysis using ANOVA). The graph is representative of 3 independent experiments.

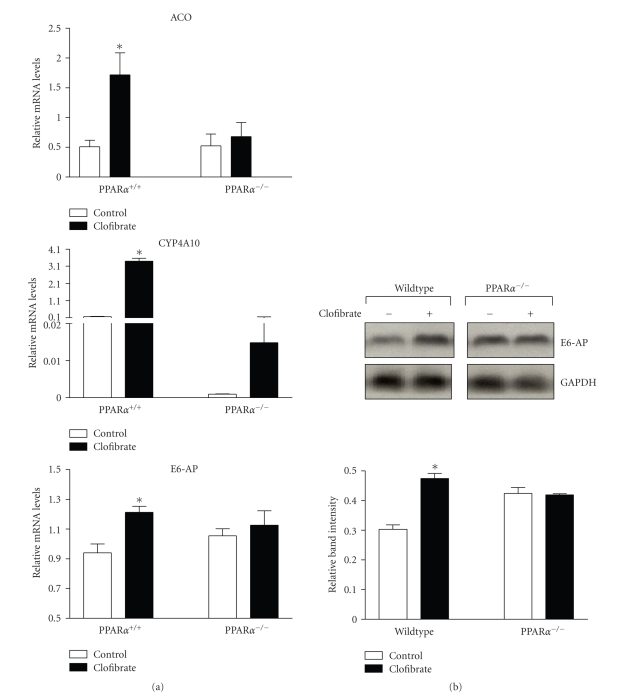

3.5. E6-AP is regulated in vivo in a PPARα-dependent manner

Since NR-mediated transcriptional regulation of E3 ligases has been demonstrated in a few studies [20–22], regulation of E6-AP in response to PPARα ligand was examined in vivo. Wild type and PPARα null mice were maintained on a clofibrate or control diet for two weeks, following which their livers were analyzed for mRNA and protein levels of E6-AP. As expected, mRNA levels of known PPARα target genes (acyl CoA oxidase or ACO and cytochrome P450 IV A10 or CYP4A10) were induced in response to clofibrate and this response was defective in PPARα null mice (Figure 5(a)). E6-AP mRNA (Figure 5(a)) and protein (Figure 5(b)) levels were significantly increased in wildtype mice in response to clofibrate, but not in PPARα null mice, indicating a PPARα-dependent regulation.

Figure 5.

E6-AP is induced by clofibrate in a PPARα-dependent manner. Wildtype and PPARα null mice were treated with control vehicle or clofibrate for 2 weeks. Groups of five mice were used for each treatment. (a) Total RNA was isolated from liver and mRNA levels were measured using real-time PCR. (b) Protein isolated from liver was analyzed for E6AP expression by western blot. The graph (lower panel) depicts mean (n = 5) band intensity. Asterisks indicate a significant increase in clofibrate induction when compared to the PPARα null group. (*P < .05 with statistical analysis using ANOVA).

4. DISCUSSION

The regulation of PPARs by the ubiquitination has been the subject of limited investigation. However, recent studies suggest ligand-mediated regulation of PPARs via the ubiquitin-proteasome system, although no ubiquitin ligase has been identified. PPARα and PPARβ ligands affect receptor ubiquitination and protein levels [23–26]. Ligand binding induces transcriptional activation of PPARγ that is followed by degradation [27]. This study identifies the E3 ubiquitin ligase E6-AP, as regulator of PPAR activity. The transcriptional activity of all three PPAR isotypes was inhibited by E6-AP. No changes were observed in ligand-induced transcriptional activity in the presence of E6-AP. PPARα and E6-AP interacted in mammalian two hybrid assays, and by using an E6-AP mutant defective in ubiquitin ligase activity, we demonstrate that inhibition of PPARα activity required the E3 ubiquitin ligase function of E6-AP. Interestingly, the presence of proteasome inhibitor MG132 had no effect on inhibition of PPARα transactivation, suggesting that the proteasomal degradation is not required for E6-AP-mediated regulation of receptor transcriptional activity. This finding points to nonproteolytic functions of ubiquitination in modulating PPARα activity. The multifaceted roles of ubiquitin in regulating protein localization, recruiting coregulators, and modifying chromatin structure are now well-recognized [7, 8, 28]. It would be of interest to examine these possibilities in regulation of PPARα function by E6-AP.

The inhibition of PPARα transcriptional activity by E6-AP is in contrast to previous findings with the progesterone receptor, where E6-AP coactivated receptor function, and the ubiquitin ligase activity was dispensable for its coactivating ability [11]. These observations suggest different mechanisms of E6-AP-mediated regulation of nuclear receptors. E6-AP is recruited to the ER-responsive pS2 promoter and is preferentially associated with E2-liganded ERα [29]. It would be of interest to determine if E6-AP is recruited to promoters of PPARα target genes, as a mechanism of transcriptional regulation. Evidence also exists for NR-mediated transcriptional regulation of E3 ligases. Estrogen activation of ERα induces the expression of two ubiquitin ligases, MDM2 and Siah2 [20–22]. MDM2 is also regulated by the thyroid hormone receptor [30] orphan receptor TR3 [31], and constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) [32]. The breast cancer associated gene (BCA2) was identified as an E3 ubiquitin ligase and BCA2 expression correlates with positive ER status in breast tumors, suggesting that BCA2 and ER might be coregulated [21]. Our study shows that E6-AP mRNA and protein levels are increased in mice in response to PPARα ligand clofibrate in wildtype but not PPARα null mice, indicating a coordinate mode of regulation between PPARα and E6-AP. In contrast to the ligand-independent decrease in PPARα transcriptional activity mediated by E6AP in FaO cells, ligand treatment resulted in an increase in E6-AP expression in mice that was PPARα-dependent. These results allude to the existence of a feedback loop between PPARα and E6-AP wherein PPARα increases the expression of a negative regulator for control of its transcriptional activity.

Studies in our laboratory have identified MDM2 as another ubiquitin ligase for PPARα (unpublished results). MDM2 regulated the transcriptional activity of PPARα by being recruited to the promoters of PPARα target genes in response to ligand, and it interacted with the A/B domain of PPARα. The various biological processes regulated by PPARs are crucial in control of disorders such as diabetes, inflammation, and cardiovascular ailments, and ubiquitin ligases such as E6-AP and MDM2 may present useful targets for pharmacological intervention and improved PPAR-based therapeutics.

In addition to contributing to understanding PPAR regulation by ubiquitination, other interesting connections can be made about the significance of the E6-AP-PPARα interaction. E6-AP mediates ubiquitination and degradation of the Hepatitis C virus (HCV) core protein, which plays a crucial role in HCV-related liver disease [33]. HCV infections are associated with reduced hepatic PPARα expression [34–37], and PPARα is implicated in HCV core protein-mediated hepatic steatosis and dysregulated lipid metabolism [37]. The regulation of PPARα by E6-AP may provide a basis for HCV-induced progression of liver disease, and is worthy of investigation.

5. CONCLUSIONS

This study identifies E6-AP, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, as a PPARα-interacting protein that inhibited ligand-independent PPARα transactivation and decreased the basal mRNA levels of PPARα target genes. The E3 ubiquitin ligase function of E6AP was required for inhibition of PPARα transcriptional activity, and this inhibition occurred in a proteasome-independent manner. E6-AP was induced in vivo in response to PPARα ligand, and was regulated in a PPARα-dependent manner. A better understanding of the role of E6-AP and other ubiquitin ligases in the regulation of PPARs could help improve treatment strategies against metabolic diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by NIH ES07799 awarded to J. P. Vanden Heuvel. The authors thank Cherie Anderson for help with mouse experiments.

References

- 1.Feige JN, Gelman L, Michalik L, Desvergne B, Wahli W. From molecular action to physiological outputs: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors are nuclear receptors at the crossroads of key cellular functions. Progress in Lipid Research. 2006;45(2):120–159. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Desvergne B, Michalik L, Wahli W. Be fit or be sick: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors are down the road. Molecular Endocrinology. 2004;18(6):1321–1332. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Escher P, Wahli W. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: insight into multiple cellular functions. Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis. 2000;448(2):121–138. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(99)00231-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu S, Reddy JK. Transcription coactivators for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2007;1771(8):936–951. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. The coregulator exchange in transcriptional functions of nuclear receptors. Genes & Development. 2000;14(2):121–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ismail A, Nawaz Z. Nuclear hormone receptor degradation and gene transcription: an update. IUBMB Life. 2005;57(7):483–490. doi: 10.1080/15216540500147163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kinyamu HK, Chen J, Archer TK. Linking the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway to chromatin remodeling/modification by nuclear receptors. Journal of Molecular Endocrinology. 2005;34(2):281–297. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.01680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rochette-Egly C. Dynamic combinatorial networks in nuclear receptor-mediated transcription. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(38):32565–32568. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R500008200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsuura T, Sutcliffe JS, Fang P, et al. De novo truncating mutations in E6-Ap ubiquitin-protein ligase gene (UBE3A) in Angelman syndrome. Nature Genetics. 1997;15(1):74–77. doi: 10.1038/ng0197-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith CL, DeVera DG, Lamb DJ, et al. Genetic ablation of the steroid receptor coactivator-ubiquitin ligase, E6-AP, results in tissue-selective steroid hormone resistance and defects in reproduction. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2002;22(2):525–535. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.2.525-535.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nawaz Z, Lonard DM, Smith CL, et al. The Angelman syndrome-associated protein, E6-AP, is a coactivator for the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1999;19(2):1182–1189. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.2.1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mani A, Oh AS, Bowden ET, et al. E6AP mediates regulated proteasomal degradation of the nuclear receptor coactivator amplified in breast cancer 1 in immortalized cells. Cancer Research. 2006;66(17):8680–8686. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Munakata T, Liang Y, Kim S, et al. Hepatitis C virus induces E6AP-dependent degradation of the retinoblastoma protein. PLoS Pathogens. 2007;3(9):1335–1347. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scheffner M, Huibregtse JM, Vierstra RD, Howley PM. The HPV-16 E6 and E6-AP complex functions as a ubiquitin-protein ligase in the ubiquitination of p53. Cell. 1993;75(3):495–505. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90384-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Y, Baleja JD. Structure and function of the papillomavirus E6 protein and its interacting proteins. Frontiers in Bioscience. 2008;13(1):121–134. doi: 10.2741/2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tien ES, Davis JW, Vanden Heuvel JP. Identification of the CREB-binding protein/p300-interacting protein CITED2 as a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α coregulator. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(23):24053–24063. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401489200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gray JP, Davis JW, II, Gopinathan L, Leas TL, Nugent CA, Vanden Heuvel JP. The ribosomal protein rpL11 associates with and inhibits the transcriptional activity of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α . Toxicological Sciences. 2006;89(2):535–546. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee SS-T, Pineau T, Drago J, et al. Targeted disruption of the α isoform of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gene in mice results in abolishment of the pleiotropic effects of peroxisome proliferators. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1995;15(6):3012–3022. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.3012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tien ES, Gray JP, Peters JM, Vanden Heuvel JP. Comprehensive gene expression analysis of peroxisome proliferator-treated immortalized hepatocytes: identification of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α-dependent growth regulatory genes. Cancer Research. 2003;63(18):5767–5780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kinyamu HK, Archer TK. Estrogen receptor-dependent proteasomal degradation of the glucocorticoid receptor is coupled to an increase in Mdm2 protein expression. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2003;23(16):5867–5881. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.16.5867-5881.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burger AM, Gao Y, Amemiya Y, et al. A novel RING-type ubiquitin ligase breast cancer-associated gene 2 correlates with outcome in invasive breast cancer. Cancer Research. 2005;65(22):10401–10412. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang J, Guenther MG, Carthew RW, Lazar MA. Proteasomal regulation of nuclear receptor corepressor-mediated repression. Genes & Development. 1998;12(12):1775–1780. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.12.1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blanquart C, Barbier O, Fruchart J-C, Staels B, Glineur C. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) turnover by the ubiquitin-proteasome system controls the ligand-induced expression level of its target genes. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(40):37254–37259. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110598200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blanquart C, Mansouri R, Fruchart J-C, Staels B, Glineur C. Different ways to regulate the PPARα stability. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2004;319(2):663–670. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Genini D, Catapano CV. Block of nuclear receptor ubiquitination: a mechanism of ligand-dependent control of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor δ activity . The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282(16):11776–11785. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609149200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rieck M, Wedeken L, Müller-Brüsselbach S, Meissner W, Müller R. Expression level and agonist-binding affect the turnover, ubiquitination and complex formation of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor β . FEBS Journal. 2007;274(19):5068–5076. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.06037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hauser S, Adelmant G, Sarraf P, Wright HM, Mueller E, Spiegelman BM. Degradation of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ is linked to ligand-dependent activation. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(24):18527–18533. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001297200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Conaway RC, Brower CS, Conaway JW. Emerging roles of ubiquitin in transcription regulation. Science. 2002;296(5571):1254–1258. doi: 10.1126/science.1067466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reid G, Hübner MR, Métivier R, et al. Cyclic, proteasome-mediated turnover of unliganded and liganded ERα on responsive promoters is an integral feature of estrogen signaling. Molecular Cell. 2003;11(3):695–707. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00090-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qi J-S, Yuan Y, Desai-Yajnik V, Samuels HH. Regulation of the mdm2 oncogene by thyroid hormone receptor. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1999;19(1):864–872. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao B-X, Chen H-Z, Lei N-Z, et al. p53 mediates the negative regulation of MDM2 by orphan receptor TR3. The EMBO Journal. 2006;25(24):5703–5715. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang W, Zhang J, Washington M, et al. Xenobiotic stress induces hepatomegaly and liver tumors via the nuclear receptor constitutive androstane receptor. Molecular Endocrinology. 2005;19(6):1646–1653. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shirakura M, Murakami K, Ichimura T, et al. E6AP ubiquitin ligase mediates ubiquitylation and degradation of hepatitis C virus core protein. Journal of Virology. 2007;81(3):1174–1185. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01684-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dharancy S, Malapel M, Perlemuter G, et al. Impaired expression of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha during hepatitis C virus infection. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(2):334–342. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng Y, Dharancy S, Malapel M, Desreumaux P. Hepatitis C virus infection down-regulates the expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α and carnitine palmitoyl acyl-CoA transferase 1A. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2005;11(48):7591–7596. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i48.7591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Gottardi A, Pazienza V, Pugnale P, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α and -γ mRNA levels are reduced in chronic hepatitis C with steatosis and genotype 3 infection. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2006;23(1):107–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rakic B, Sagan SM, Noestheden M, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α antagonism inhibits hepatitis C virus replication. Chemistry & Biology. 2006;13(1):23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]