Abstract

BACKGROUND

Antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) and quantitative monitoring of antimicrobial use are required to ensure that antimicrobials are used appropriately in the acute care setting, and have the potential to reduce costs and limit the spread of antimicrobial-resistant organisms and Clostridium difficile. Currently, it is not known what proportion of Quebec hospitals have an ASP and/or monitor antimicrobial use.

OBJECTIVES

To determine what proportion of Quebec hospitals have an ASP, and what is the nature of such a program.

METHODS

A detailed questionnaire was sent to the pharmacy directors of all acute care hospitals in the province of Quebec. Information was collected on antimicrobial surveillance; antimicrobial stewardship and resource allocation to these areas were assessed.

RESULTS

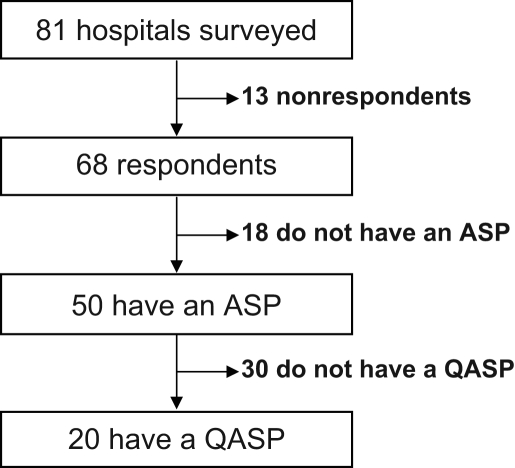

Questionnaires were completed for 68 of 81 (84%) hospitals contacted. ASPs were identified at 50 (74%) hospitals, but only 20 (29%) of hospitals had a quantitative antimicrobial surveillance program (QASP) in 2006. Academic centres (P=0.03) and hospitals with over 200 beds (P=0.02) were more likely to have a QASP. Even among hospitals with an ASP, 18% had less than one full-time pharmacist for a QASP.

CONCLUSIONS

Over one-quarter of Quebec hospitals do not have an ASP, and few hospitals in Quebec are currently evaluating their use of antimicrobials on a quantitative basis. In some cases, the lack of a QASP may be due to the allocation of insufficient pharmaceutical resources to antimicrobial stewardship (ie, less than one full-time pharmacist).

Keywords: Antimicrobials, Antimicrobial stewardship, Guidelines, Survey

Abstract

HISTORIQUE

Un programme d’optimisation de l’utilisation des antibiotiques (ASP) et un système de surveillance quantitative des antibiotiques sont essentiels pour assurer une bonne utilisation des antibiotiques en centre de soins aigus. De plus, ils peuvent réduire les coûts, l’émergence de pathogènes résistants et la diarrhée associée au Clostridium difficile. Actuellement, la proportion d’hôpitaux de la province de Québec avec un ASP est inconnue.

OBJECTIFS

Déterminer la proportion de centres de soins aigus dotés d’un ASP et en définir les caractéristiques.

MÉTHODOLOGIE

Un questionnaire détaillé a été soumis au directeur de la pharmacie de tous les centres de soins aigus du Québec. La collecte de données concernait les sujets suivants: la surveillance des antibiotiques, les caractéristiques des ASP et les ressources allouées.

RÉSULTATS

Les questionnaires ont été remplis et retournés par 68 des 81 (84 %) hôpitaux sondés. Un ASP était présent dans 50 (74 %) centres, mais seulement 20 (29 %) avaient un programme de surveillance quantitative des antibiotiques (QASP) en 2006. Les centres universitaires (p=0,03) et les hôpitaux de plus de 200 lits (p=0,02) étaient plus susceptibles d’être dotés d’un QASP. Même dans les centres dotés d’un ASP, 18 % étaient pourvus de moins d’un pharmacien à temps plein pour la surveillance quantitative.

CONCLUSION

Plus du quart des hôpitaux au Québec n’avaient pas d’ASP et peu d’hôpitaux évaluaient quantitativement l’utilisation des antibiotiques. Dans certains cas, l’absence de QASP pourrait être justifiée par le manque d’effectifs attribués à l’optimisation de l’utilisation des antibiotiques (c.-à-d., moins d’un pharmacien à temps plein).

Antimicrobials are one of the most commonly used classes of drugs in Canadian hospitals. Published data (1,2) report that over 25% of hospitalized patients receive an antimicrobial, representing 12% to 20% of a hospital’s drug acquisition budget. From the Canadian MIS Database, a Canadian Institute for Health Information database, the percentage of a hospital’s drug acquisition budget for antimicrobials for the fiscal year 2004/2005 was an average of 9% nationally, with provincial ratios ranging from 6% to 14% (personal communication). A considerable proportion of antimicrobial use in hospitalized patients is inappropriate (3–5). The Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America recommend that hospitals should institute antimicrobial optimization programs to improve patient outcomes (6,7). Guidelines for developing these programs were recently released by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (8). However, prior surveys of American hospitals have found that practices to improve antimicrobial use were frequently inadequate or not routinely implemented (9,10). In Quebec, a province-wide outbreak of Clostridium difficile resulted in the development of a provincial action plan for the prevention and control of nosocomial infections that included recommendations on antimicrobial optimization (10,11). The goal of the present survey was to evaluate the current status of antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) and quantitative antimicrobial surveillance programs (QASPs) in Quebec.

METHODS

Study population

Questionnaires were sent to the director of pharmacy at all acute care hospitals in Quebec, including small community centres. If a centre had more than one physical site, a survey was sent to each site; directors of pharmacy in charge of more than one hospital were asked to answer a separate survey for each site.

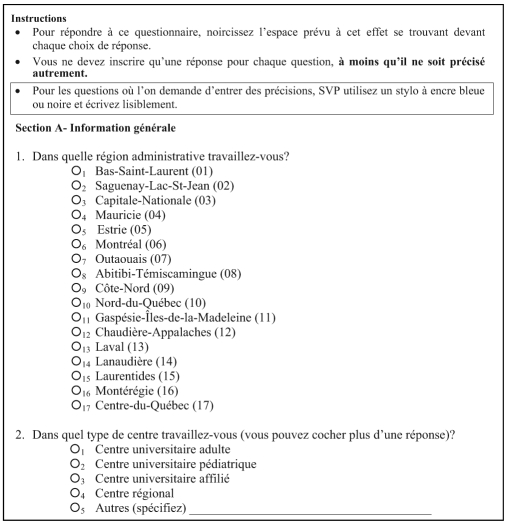

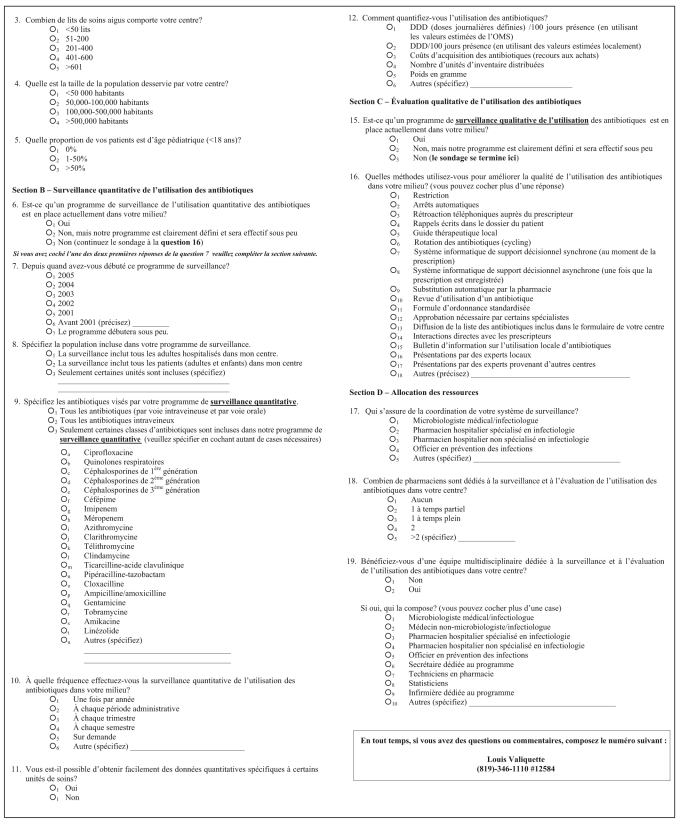

Questionnaire (Appendix 1)

The questionnaire was developed based on review articles that identified the key elements of an ASP (7,12) and through group discussions with local experts. The survey was reviewed by infectious diseases specialists and pharmacists to ensure clarity and ease of use. It consisted of 19 multiple choice questions that collected information on hospital size and patient population, antimicrobial surveillance and antimicrobial stewardship, as well as assessed the resources allocated to these areas.

Study protocol

The survey was mailed to all identified directors of pharmacy in February 2006. Surveys unanswered within four weeks were followed up with a mailed reminder, followed two weeks later by a phone reminder. Each mailing included a preaddressed and prepaid return envelope.

Statistical analysis

All completed surveys were entered into a Microsoft Access 2003 (Microsoft Corporation, USA) database. Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, USA). The χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare proportions, as appropriate.

RESULTS

Eighty-one acute care hospitals in the province of Quebec were surveyed. Completed questionnaires from 68 of 81 (84%) hospitals were received, including hospitals from all 17 Quebec administrative regions ensuring a wide geographical distribution of respondents (Figure 1). After the initial distribution, 59 (73%) surveys were received. Nine (11%) additional responses were obtained after sending postcards and performing phone reminders.

Figure 1.

Details of surveyed hospitals. ASP Antimicrobial stewardship program; QASP Quantitative antimicrobial surveillance program

Hospital baseline data

Of the respondents, 49 (72%) were working in a regional hospital, and 19 (28%) were working in a university or university-affiliated centre. The majority of surveyed hospitals had less than 200 beds (n=38 [56%]), while seven (10%) had more than 600 beds. Only 11 (16%) centres were serving a population over 500,000 inhabitants. No hospital surveyed was exclusively devoted to a pediatric population, but 47 (69%) had a mixed population (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Hospitals’ demographics (n=68)

| Demographics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Hospital size | |

| <200 beds | 38 (56) |

| 200–400 beds | 18 (26) |

| >400 beds | 12 (18) |

| Affiliated to an academic center | |

| Yes | 19 (28) |

| No | 49 (72) |

| Size of community | |

| <50,000 | 25 (37) |

| 50,000–100,000 | 7 (10) |

| 100,001–500,000 | 25 (37) |

| >500,000 | 11 (16) |

QASP

Overall, 15 (22%) respondents had an active QASP, although only six (9%) had been functional for longer than five years. Five centres (7%) were in the process of implementing a QASP at the time of the survey. Consequently, they were included in the results. Academic centres frequently operated a QASP (43% versus 22%; P=0.03), as did hospitals with more than 200 beds (43% versus 18%; P=0.02). Most centres, 12 of 20 (60%), monitored all patients regardless of their age, six (30%) excluded all pediatric patients, and two (10%) performed surveillance only in high-risk wards and units. A majority of centres (70%) included all intravenous and oral antimicrobials in their surveillance. In nine (45%) centres, surveillance was performed once per financial cycle of 12 months. Four centres (20%) had the ability to process ‘on demand’ queries, and 12 (60%) were able to obtain quantitative data for specific wards. To estimate antimicrobial consumption, most of the centres relied on either the number of distributed units, acquisition costs or defined daily doses per 100 patient-days. Professionals in charge of QASPs were accountable to a number of different health professionals, committees and/or members of hospital administration (median 3.5 persons/hospital), the most frequent being the pharmacy and therapeutic committee, members of the department of pharmacy and the hospital infection control committee. All centres with or planning to have a QASP had an ASP (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Hospitals with an established quantitative antimicrobial surveillance program (QASP)

| QASP characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Year of implementation (n=20) | |

| Before 2001 | 6 (30) |

| 2001–2004 | 4 (20) |

| 2005 | 5 (25) |

| Will start soon | 5 (25) |

| Measurement unit used to quantify antimicrobials (n=20)* | |

| Number of units distributed | 9 (45) |

| Defined daily doses per 100 patients-days using the World Health Organization estimated value | 8 (40) |

| Acquisition cost | 7 (35) |

| Other | 3 (15) |

| Results are presented to the*: | |

| Pharmacy and therapeutics committee | 14 (70) |

| Pharmacy department | 13 (65) |

| Infection control committee | 10 (50) |

| Head of the medical microbiology/infectious diseases service | 10 (50) |

| Council of physicians, dentists and pharmacists’ executive committee† | 9 (45) |

| Director of professional services | 8 (40) |

| Hospital director | 5 (25) |

| Other | 5 (25) |

More than one possible answer per participant;

In Quebec hospitals, this council has a similar function to that of the medical advisory executive committee

ASP

Interventions to optimize antimicrobial utilization were used in 50 of 68 hospitals (74%) and were more commonly used in academic than in nonacademic hospitals (84% versus 69%, P=0.35). All hospitals routinely performing any intervention to improve the antimicrobial usage were considered to have an ASP. The most common interventions were direct interaction with the prescribing physician (86%), automatic stop orders (54%) and automatic substitution (40%) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Antimicrobial stewardship program (ASP) strategies used by surveyed centres (n=50)

| Strategies included in the ASP* | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Direct interaction with the prescriber | 43 (86) |

| Written reminders | 28 (56) |

| Phone feedback to the prescriber | 21 (42) |

| Education | 30 (60) |

| Automatic stop orders | 27 (54) |

| Automatic substitution | 20 (40) |

| Formulary restriction | 20 (40) |

| Local guidelines | 20 (40) |

| Preauthorization requirements | 14 (28) |

| Antimicrobial cycling | 1 (2) |

| Decision support systems | 1 (2) |

More than one possible answer per participant

Clinical pharmacists coordinated the ASPs 57% of the time, but pharmacists specialized in infectious diseases only 17% of the time. A multidisciplinary antimicrobial stewardship team was in place in 36% of responding hospitals. Members of these teams were usually infectious diseases specialists (89%), clinical pharmacists (72%) or other physicians (44%). The majority of hospitals (82%) allocated less than one full-time pharmacist to ASPs (Table 3). In the subgroup of hospitals with more than 200 beds, there were still 17 centres (68%) with less than one dedicated full-time pharmacist (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Hospitals with an antimicrobial stewardship program (ASP)

| ASP characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Coordinator of the ASP (n=47)* | |

| Pharmacist | 27 (57) |

| Infectious diseases specialist | 14 (30) |

| Pharmacist specialized in infectious diseases | 8 (17) |

| Infection control officer | 2 (4) |

| Other | 5 (11) |

| Number of pharmacists dedicated to ASPs (n=49)* | |

| Less than one full-time | 40 (82) |

| At least one full-time | 9 (18) |

| Members of a multidisciplinary team (n=18)* | |

| Infectious diseases specialist | 16 (89) |

| Hospital pharmacist | 17 (94) |

| General clinical pharmacist | 13 (72) |

| Clinical pharmacist with infectious diseases training | 7 (39) |

| Physician not specialized in infectious diseases | 8 (44) |

| Other | 8 (44) |

More than one possible answer per participant

DISCUSSION

ASPs were present in most acute care hospitals in Quebec, although at the time this study was performed, only 15 (22%) were capable of quantitatively evaluating antimicrobial consumption, and only eight (12%) were using units such as defined daily doses per 100 bed-days that would allow benchmarking and comparison with other centres. Although strongly recommended in the Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines (8), few hospitals had a multidisciplinary team directing the ASP; the ASP was often directed by a pharmacist without specific infectious diseases training, and over 80% of ASPs were allocated less than one full-time pharmacist. Even at hospitals with a QASP, only 25% of ASPs reported the results of the QASP to the hospital directors.

Given the high response rate to our survey (84%) and our assessment of acute care facilities over a wide geographical area, our results should be generalizable. This high response rate indicates, in our point of view, the interest of chief pharmacists in ASPs. Furthermore, because we assessed hospitals in all regions of Quebec, our results should be useful when evaluating the implementation of a province- or state-based antimicrobial control policy. This is the first published survey examining QASP practices in North America. Other surveys have been performed in the United States, but most of them targeted academic centres and evaluated only ASPs, not QASPs. Therefore, it is difficult to compare our results with previous surveys. Nevertheless, some important differences must be highlighted. First, there is a more frequent use of restriction policies and protocols in American surveyed centres – 64% to 81% compared with 40% in our survey (9,10). Second, Lesar and Briceland (9) reported that only 6% (three of 48) of university-affiliated centres did not have any official recommendations on antimicrobial use compared with 16% (three of 19 Quebec university-affiliated centres) in our survey. It suggests that antimicrobial stewardship is more widely implemented in American university centres. Managed care and liability issues may partly explain these differences.

In January 2005, 30 Quebec centres had a rate of nosocomial C difficile-associated disease (CDAD) higher than 15 cases per 10,000 patient-days (13). There are very few evidence-based strategies reported to prevent and control CDAD – one is to implement antimicrobial policies (14). This is not surprising because antimicrobial intake within two months of diagnosis is the most important risk factor for developing CDAD (15). Our results are concerning, given that they were obtained more than two years after a widely publicized and devastating CDAD outbreak that plagued hospitals across the province of Quebec (16,17). Resources should be allocated to optimizing antimicrobial therapy; this approach could have an important impact on emerging infection control challenges such as the appearance and spread of hypervirulent strains of C difficile within hospitals worldwide.

Because our survey was restricted to acute care hospitals in Quebec, our results may not be generalizable outside Quebec or to long-term care facilities. Although some hospitals have added ASPs and QASPs since our survey, our results likely reflect the current state of antimicrobial management in Quebec hospitals because we included centres in the process of developing and implementing such programs in our results.

The present survey targets current strengths and weaknesses of ASPs in Quebec. Even if a provincial network of antimicrobial consumption based on the number of defined daily doses per 1000 patients-days provided inestimable data, it would use up a lot of pharmacists’ time and energy, and would not provide short-term improvement in antimicrobial prescriptions. Because optimization programs are already established in most centres, a good start would be to delineate the important components of these programs (eg, local practice guidelines, multidisciplinary teams, feedback to prescribers and intravenous to oral changes). We identified that 86% of centres provided direct feedback to the prescribers. Given the time required to perform such strategies, it is discordant with the lack of resources reported. Should this strategy be prioritized or other more efficient options be considered? Identifying central components to optimization programs should improve the performance of the actual ASP and facilitate the instauration of new programs. Finally, it would allow realistic short-term objectives to be met in quality improvement and antimicrobial consumption monitoring using fewer resources.

Ten years after the jointly published guidelines (7) by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America and Infectious Diseases Society of America, it is disappointing to see that more than one-quarter of Quebec acute care centres do not have any type of antimicrobial improvement program. Moreover, only a slight minority of centres, mostly academic and tertiary, are quantitatively evaluating their antimicrobial consumption. This situation highlights an important gap between the Health Ministry’s expectations and the current situation in Quebec acute care hospitals. It is unimaginable to conceive the implementation of a QASP or an efficient ASP without the inclusion of pharmacists and/or physicians with infectious diseases and microbiology training. The participation of less than one full-time pharmacist may be sufficient for very small centres, but it is not, in our opinion, sufficient for acute care centres with more than 200 beds.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Matthew Muller for his critical appraisal of this manuscript.

APPENDIX 1

Footnotes

FUNDING/SUPPORT: Dr Valiquette is a member of the Fonds de Recherche en Santé du Québec-funded Centre de recherche clinique Étienne-Le Bel. This study has been funded through the Fonds de Recherche en Santé du Québec/Conseil du Médicament du Québec.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rotstein C, Salama S, Mandell L, Cimino M. An integrated approach to antimicrobial stewardship in hospital setting. Can J Infect Dis. 1998;9(Suppl C):7–16. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoffman JM, Shah ND, Vermeulen LC, et al. Projecting future drug expenditures – 2007. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64:298–314. doi: 10.2146/ajhp060545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.John JF, Jr, Fishman NO. Programmatic role of the infectious diseases physician in controlling antimicrobial costs in the hospital. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:471–85. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.3.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Willemsen I, Groenhuijzen A, Bogaers D, Stuurman A, van Keulen P, Kluytmans J. Appropriateness of antimicrobial therapy measured by repeated prevalence surveys. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:864–7. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00994-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pulcini C, Cua E, Lieutier F, Landraud L, Dellamonica P, Roger PM. Antibiotic misuse: A prospective clinical audit in a French university hospital. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;26:277–80. doi: 10.1007/s10096-007-0277-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marr JJ, Moffet HL, Kunin CM. Guidelines for improving the use of antimicrobial agents in hospitals: A statement by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. J Infect Dis. 1988;157:869–76. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.5.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shlaes DM, Gerding DN, John JF, Jr, et al. Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America and Infectious Diseases Society of America Joint Committee on the Prevention of Antimicrobial Resistance: Guidelines for the prevention of antimicrobial resistance in hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:584–99. doi: 10.1086/513766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dellit TH, Owens RC, McGowan JE, Jr, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America; Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America guidelines for developing an institutional program to enhance antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:159–77. doi: 10.1086/510393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lesar TS, Briceland LL. Survey of antibiotic control policies in university-affiliated teaching institutions. Ann Pharmacother. 1996;30:31–4. doi: 10.1177/106002809603000105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lawton RM, Fridkin SK, Gaynes RP, McGowan JE., Jr Practices to improve antimicrobial use at 47 US hospitals: The status of the 1997 SHEA/IDSA position paper recommendations. Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America/Infectious Diseases Society of America. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2000;21:256–9. doi: 10.1086/501754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Direction générale de la santé publique du ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux. Plan d’action sur la prévention et le contrôle des infections nosocomiales 2006–2009. Québec: Direction des communications, ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux, 2006.

- 12.Davey P, Brown E, Fenelon L, et al. Interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing practices for hospital inpatients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(4):CD003543. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003543.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Institut national de santé publique du Québec. Surveillance des diarrhées associées à Clostridium difficile au Québec – Résultats du 22 août 2004 au 5 février 2005. < http://www.inspq.qc.ca/pdf/publications/370-ResultatsCDifficile-22Aout2004-05Fevrier2005.pdf> (Version current at April 1, 2008)

- 14.Gerding DN, Johnson S, Peterson LR, Mulligan ME, Silva J., Jr Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea and colitis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1995;16:459–77. doi: 10.1086/648363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poutanen SM, Simor AE. Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in adults. CMAJ. 2004;171:51–8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pépin J, Valiquette L, Alary ME, et al. Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in a region of Quebec from 1991 to 2003: A changing pattern of disease severity. CMAJ. 2004;171:466–72. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1041104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loo VG, Poirier L, Miller MA, et al. A predominantly clonal multi-institutional outbreak of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea with high morbidity and mortality. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2442–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051639. (Erratum in 2006;354:2200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]