Abstract

Many G-protein-coupled receptors, including the α1b-adrenoceptor, form homo-dimers or oligomers. Mutation of hydrophobic residues in transmembrane domains I and IV alters the organization of the α1b-adrenoceptor oligomer, with transmembrane domain IV playing a critical role. These mutations also result in endoplasmic reticulum trapping of the receptor. Following stable expression of this α1b-adrenoceptor mutant, cell surface delivery, receptor function and structural organization were recovered by treatment with a range of α1b-adrenoceptor antagonists that acted at the level of the endoplasmic reticulum. This was accompanied by maturation of the mutant receptor to a terminally N-glycosylated form, and only this mature form was trafficked to the cell surface. Co-expression of the mutant receptor with an otherwise wild-type form of the α1b-adrenoceptor that is unable to bind ligands resulted in this wild-type variant also being retained in the endoplasmic reticulum. Ligand-induced cell surface delivery of the mutant α1b-adrenoceptor now allowed co-recovery to the plasma membrane of the ligand-binding-deficient mutant. These results demonstrate that interactions between α1b-adrenoceptor monomers occur at an early stage in protein synthesis, that ligands of the α1b-adrenoceptor can act as pharmacological chaperones to allow a structurally compromised form of the receptor to pass cellular quality control, that the mutated receptor is not inherently deficient in function and that an oligomeric assembly of ligand-binding-competent and -incompetent forms of the α1b-adrenoceptor can be trafficked to the cell surface by binding of a ligand to only one component of the receptor oligomer.

Keywords: endoplasmic reticulum retention, G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), glycosylation, pharmacological chaperone

Abbreviations: α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV, a form of the hamster α1b-adrenoceptor containing point mutations (L1.52A, V1.53A) in transmembrane domain I and (L4.46A, L4.47A) in transmembrane domain IV; BFA, brefeldin A; DMEM, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium; eCFP, enhanced cyan fluorescent protein; EndoH, endoglycosidase H; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; eYFP, enhanced yellow fluorescent protein; FRET, fluorescence resonance energy transfer; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; GPCR, G-protein-coupled receptor; [35S]GTP[S], [35S]guanosine 5′-[γ-thio]triphosphate; HEK cell, human embryonic kidney cell; NGaseF, N-glycosidase F; TM, transmembrane domain

INTRODUCTION

It is now widely accepted that many GPCRs (G-protein-coupled receptors) can form dimers and/or higher order oligomers [1,2]. The importance of this for function is currently an area of intense investigation, with suggested roles for dimerization/oligomerization including both providing the most appropriate footprint for G-protein binding and enhancing the effectiveness of signal transduction [3]. A further area in which GPCR dimerization/oligomerization may play a key role is in the processes involved in receptor folding, maturation and effective transfer to the plasma membrane [4,5]. In this scenario, protein–protein interactions are likely to be initiated early in the biosynthetic process. Evidence in favour of this model includes the well appreciated ‘dominant-negative’ effects of either naturally occurring or designed, truncated or otherwise mutated GPCRs in restricting cell surface delivery of co-expressed, wild-type forms of the receptor [6,7]. Furthermore, in the case of the most widely studied GPCR heterodimer, the functional GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid) b receptor [8] is only generated and delivered to the cell surface when the GABAbR1 polypeptide, that contains an ER (endoplasmic reticulum)-retention motif within the intracellular C-terminal tail, interacts with the GABAbR2 polypeptide which acts to mask this retention sequence [9].

A number of human diseases are associated with mutations in GPCRs that result in intracellular retention of the receptor due to a lack of effective folding and receptor maturation. These include nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, in which a wide range of mutations in the V2 vasopressin receptor result in this condition [10], as well as cases of retinitis pigmentosa (mutants of rhodopsin) [11] and hypergonadotrophic hypergonadism (mutants of the gonadotrophin-releasing hormone receptor) [12]. In recent times, so-called ‘pharmacological chaperones’, cell-permeant ligands with affinity for the GPCR in question, have been used to recover a number of such receptor point mutants to the cell surface, with the hope and expectation that this might be sufficient to allow the receptor to function normally and respond to endogenously produced agonist ligands [13–17].

Certain GPCR mutants that appear to be compromised in structural organization or dimerization also display improper cell surface delivery [18,19]. It is thus conceptually possible that pharmacological chaperones could rescue the cell surface delivery and function of dimerization/oligomerization-impaired receptor mutants. This hypothesis has not, however, previously been tested, but could be employed to assess if GPCRs are delivered to the surface of cells as pre-formed dimers/oligomers. In recent studies on transmembrane elements important for efficient dimerization/oligomerization of the α1b-adrenoceptor, we generated a variant containing point mutations in both TMI (transmembrane domain I) and TMIV (transmembrane domain IV) that had a defect in structural organization, consistent with altered oligomerization, as monitored by the use of single cell sequential 3-colour FRET (fluorescence resonance energy transfer) imaging [18]. We went on to show that the mutations in TMIV (L166A, L167A: L4.46A, L4.47A in the Ballesteros and Weinstein nomenclature) [20] were principally responsible for this effect.

Following stable expression of this mutant in HEK (human embryonic kidney)-293 cells, we now demonstrate that it is trapped in the ER/Golgi as an immature protein and that treatment of these cells with ligands with affinity for the α1b-adrenoceptor results in maturation of the mutant to a form that is able to pass cellular quality control and reach the cell surface, and which FRET studies suggest has structural organization akin to the wild-type α1b-adrenoceptor. These ligands hence function as ‘pharmacological chaperones’ [14–17] for the mutant receptor. Furthermore, this mutant acts as a selective ‘dominant-negative’, preventing cell surface delivery of co-expressed wild-type forms of the α1b-adrenoceptor. Because a pharmacological chaperone ligand allows the co-trafficking of the mutant that lacks correct structural organization in the absence of the ligand and a co-expressed form of the wild-type α1b-adrenoceptor that is unable to bind the ligand, these data demonstrate that the α1b-adrenoceptor traffics to the cell surface as a dimeric/oligomeric complex [4] and suggest that effective dimerization/oligomerization may be integral to the production of the functional cell surface α1b-adrenoceptor.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

All materials for tissue culture were from Invitrogen. [3H]Prazosin was from Perkin Elmer Life Sciences. All drugs used were from Sigma–Aldrich.

Constructs, cell culture and transfection

Wild-type and mutant (with L1.52A, V1.53A and L4.46A, L4.47A mutations; α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV) forms of the α1b-adrenoceptor fused to eYFP (enhanced yellow fluorescent protein) were described previously [18]. HEK-293 cells were transfected using Effectene (Qiagen) transfection reagent and subsequently selected for resistance to geneticin. The Myc-D125A (D3.32A) α1b-adrenoceptor-Y67C-eYFP mutant was generated using the QuikChange® site-directed mutagenesis kit from Stratagene.

Subcellular compartments: staining and immunocytochemistry

Cells on poly-D-lysine-coated coverslips were rinsed twice with PBS. Cell nuclei were stained by incubating the cells for 20 min at 37 °C with fresh PBS containing the nuclear DNA-binding dye Hoechst 33342 (Molecular Probes) (10 μg/ml). Cells were then washed 3–4 times with PBS, fixed in 4% formaldehyde/PBS for 10 min and washed three times with ice-cold PBS prior to the blocking step performed with 3% (w/v) non-fat dried skimmed milk powder in PBS for 10 min. Cells were incubated with a rabbit anti-FLAG polyclonal antibody (1:100, Sigma–Aldrich) for 1 h at room temperature (22 °C) and then washed twice with PBS. Cells were then incubated for 1 h with an Alexa594-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (1:400) (Molecular Probes). After washing with PBS, coverslips mounted on to glass slides were viewed using an epifluorescence microscope. For ER staining, after nuclear labelling cells were rinsed twice with PBS and incubated at 37 °C for a further 30 min with an ER-Tracker Red dye (Molecular Probes).

Cell surface receptor measurement: ELISA

Cells were grown in 96-well poly-D-lysine-coated plates and treated as described in the Figure legends. Cell surface receptors were labelled with anti-FLAG antibody (1:1000) in growth medium for 30 min at 30 °C. The cells were then washed once with 20 mM Hepes/DMEM (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium) and then incubated for 30 min at 37 °C in growth medium supplemented with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG as secondary antibody and 1 μM Hoechst nuclear stain. The cells were then washed twice with PBS and Hoechst fluorescence was measured. Finally, the cells were incubated with SureBlue (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD, U.S.A.) for 5 min in the dark at room temperature and then the absorbance was read at 620 nm using a Victor2 plate reader (PerkinElmer).

Cell lysates

Cell lysates were obtained by harvesting the cells with ice-cold RIPA buffer [50 mM Hepes, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, and 0.5% sodium deoxycholate supplemented with 10 mM NaF, 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM NaH2PO4, 5% ethylene glycol and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete; Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), pH 7.4]. Cellular extracts were then centrifuged for 30 min at 14000 g and the supernatant was recovered.

Cell surface biotinylation experiments

For cell surface biotinylation, cells were grown in 6-well plates coated with poly-D-lysine and treated as stated. Confluent cells were washed with ice-cold borate buffer (10 mM boric acid, 154 mM NaCl, 7.2 mM KCl and 1.8 mM CaCl2, pH 9.0) and incubated on ice with 1 ml of 0.8 mM EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-SS-Biotin (Pierce) in borate buffer for 15 min. The cells were then rinsed with a 0.192 M glycine and 25 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8.3) solution to quench the excess of biotin and then lysed with RIPA buffer. Lysates were centrifuged for 30 min at 14000 g and the supernatant was recovered. An aliquot of the lysates was saved for Western blotting. Biotinylated cell surface proteins were isolated using 100 μl of immunopure immobilized streptavidin (Pierce). After 1 h incubation at 4 °C with constant rotation, samples were centrifuged and the streptavidin beads were washed 3 times with RIPA buffer. Finally the biotinylated proteins were eluted with 100 μl of SDS sample buffer for 1 h at 37 °C.

Cell treatments

Deglycosylation treatments were carried out using NGaseF (N-glycosidase F) or EndoH (endoglycosidase H) (Roche Diagnostics) for an overnight period at final concentrations of 1 unit/μl or 100 m-units/ml respectively. Tunicamycin and BFA (brefeldin A) treatments were performed by overnight incubation with 12 μM or 5 μg/ml respectively.

[Ca2+]i ratio imaging and [Ca2+]i mobilization assays

HEK-293 cells stably expressing FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP or FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP were plated on to coverslips where they grew for 24 h prior to experimentation. Cells were loaded with the Ca2+-sensitive dye Fura-2 AM (1.5 μM), by incubation (30 min; 37 °C) under reduced light in DMEM growth medium. Calcium ratio imaging and image analysis were then performed as described previously [18]. For FlexStation (Molecular Devices, Sunnydale, CA, U.S.A.) experiments, cells were grown in 96-well plates and, 24 h after seeding, cells were loaded with the calcium-sensitive dye Fura-2 AM as above.

Membrane preparations

Cells were collected by centrifugation (1700 g, 5 min, 4 °C), frozen at −80 °C for at least 1 h and resuspended in 10 mM Tris/HCl and 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4 buffer. Cell suspensions were homogenized using an Ultra Turrax for 3×20 s. The homogenate was centrifuged at 1700 g for 10 min, and the supernatant collected and centrifuged at 48000 g for 45 min at 4 °C. The resulting pellet was resuspended in buffer and stored at −80 °C.

[3H]Prazosin binding studies

Binding assays were initiated by the addition of 15–20 μg of cell membranes to an assay buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl, 100 mM NaCl and 3 mM MgCl2, pH 7.4) containing [3H]prazosin (0.02–1 nM in saturation assays and 0.4 nM for competition assays) in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of phenylephrine. Non-specific binding was determined in the presence of 100 μM phentolamine. Reactions were incubated for 60 min at 30 °C, and bound ligand was separated from free by vacuum filtration through GF/B filters (Semat, St. Albans, Hertfordshire, U.K.). The filters were washed twice with assay buffer, and bound ligand was estimated by liquid scintillation spectrometry.

[35S]GTP[S] ([35S]guanosine 5′-[γ-thio]triphosphate) binding studies

[35S]GTP[S] binding experiments were initiated by the addition of membranes to an assay buffer {20 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), 3 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl, 1 μM GDP, 0.2 mM ascorbic acid and 100 nCi of [35S]GTP[S]} containing the indicated concentrations of receptor ligands. Reactions were incubated for 15 min at 30 °C and terminated by the addition of 0.5 ml of ice-cold buffer containing 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), 3 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl and 0.2 mM ascorbic acid. The samples were centrifuged at 16000 g for 15 min at 4 °C, and the resulting pellets resuspended in solubilization buffer (100 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.4, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA and 1.25% Nonidet P-40) plus 0.2% SDS. Samples were pre-cleared with Pansorbin (Calbiochem) followed by immunoprecipitation with an anti-Gq/G11 antiserum [21]. Finally, the immunocomplexes were washed twice with solubilization buffer, and bound [35S]GTP[S] was measured.

Sequential 3-colour FRET studies

Sequential 3-colour FRET studies were performed as described by Lopez-Gimenez et al. [18] following transient co-expression of C-terminally eCFP (enhanced cyan fluorescent protein), eYFP and dsRed2-tagged and N-terminally FLAG-tagged forms of either the wild-type or mutant α1b-adrenoceptors in HEK-293 cells.

RESULTS

Cellular location of an α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV mutant and its plasma membrane delivery by a pharmacological chaperone

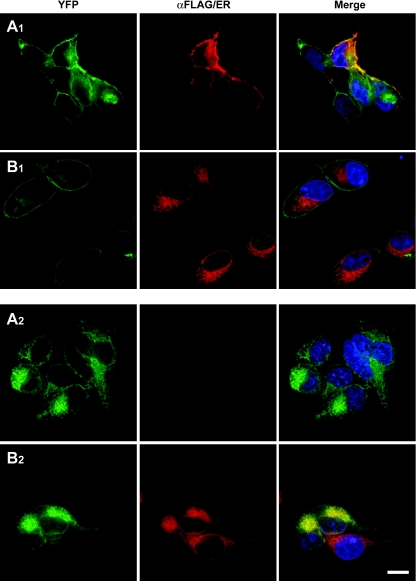

We have recently described a form of the α1b-adrenoceptor containing mutations in both TMI (L1.52A, V1.53A) and TMIV (L4.46A, L4.47A) (α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV) that, based on FRET data, result in alteration of its quaternary structure and defective receptor maturation and delivery to the plasma membrane following transient transfection [18]. To investigate this further, we stably expressed N-terminally FLAG-tagged and C-terminally eYFP-tagged forms of wild-type α1b-adrenoceptor (Figures 1A1 and 1B1) and the TMI-TMIV mutant (Figures 1A2 and 1B2) in HEK-293 cells. Immunocytochemistry with anti-FLAG in fixed non-permeabilized cells confirmed cell surface delivery of a proportion of wild-type FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP (Figure 1A1). In contrast, no cell surface FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP could be detected (Figure 1A2). In the same cells, visualization of the eYFP linked to each form of the receptor showed that FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP was distributed throughout delineated intracellular compartments (Figures 1A2 and 1B2), whereas FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP was located at both the plasma membrane and in intracellular locations (Figures 1A1 and 1B1). Plasma membrane delivery of wild-type FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP was confirmed further by the strong overlap at the cell surface of anti-FLAG-immunoreactivity and eYFP fluorescence in non-permeabilized cells (Figure 1A1). Merging of the eYFP signal in cells stained with a red ER-defining dye suggested that FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP was mainly retained in this compartment (Figure 1B2), whereas this was not the case for wild-type FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP (Figure 1B1).

Figure 1. ER retention of FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP.

Anti-FLAG immunocytochemistry (FLAG, A1, A2, red) or ER labelling (ER, B1, B2, red) of HEK-293 cells stably expressing either wild-type FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP (A1, B1) or FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP (A2, B2). Anti-FLAG staining was performed on non-permeabilized cells and where detected represents receptor at the cell surface. This was only observed in cells expressing wild-type FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP (A1), whilst parallel imaging of eYFP fluorescence (eYFP, A1, B1, A2, B2, green) confirmed cellular expression of both forms of the receptor. Merging (Merge) of red and green images confirmed cell surface delivery only of FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP (Merge, A1, yellow) or merging of red and green images indicated co-localization of FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP with the ER marker (Merge, B2, yellow). Blue represents nuclear staining with the DNA-binding dye Hoechst 33342. The scale bar in B2 corresponds to 100 μm.

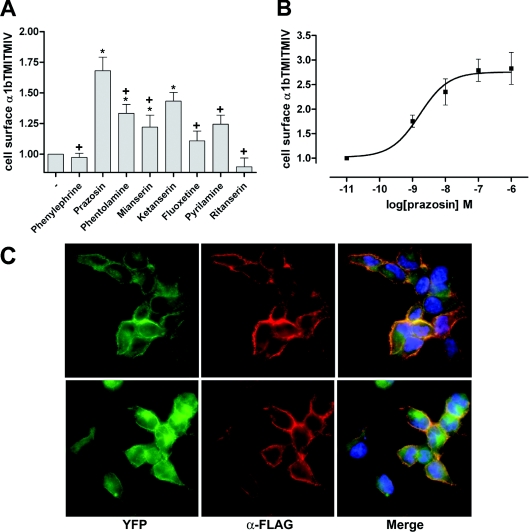

Mutations resulting in intracellular retention, as well as the ability of some chemicals and/or specific ligands to recover cell surface expression of such mutants, have been described for a number of GPCRs [13–17]. Therefore, in order to evaluate whether FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP could be trafficked to the cell surface by pharmacological means, we tested several compounds with affinity at the α1b-adrenoceptor, using a fixed concentration of 10−5 M of each in the initial screens. Intact cell anti-FLAG ELISA experiments indicated that antagonists with higher affinity for the α1b-adrenoceptor were the most effective in increasing cell surface FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP (Figure 2A). For example, although the two 5-hydroxytryptamine-receptor-selective blockers tested, ketanserin and ritanserin, are known to display some affinity for the α1b-adrenoceptor, only ketanserin caused significant cell surface delivery of the mutant receptor, consistent with its higher affinity at the α1b-adrenoceptor (15 nM compared with 190 nM respectively). Because prazosin, along with ketanserin, was the most effective ligand tested in acting as a pharmacological chaperone for FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP (Figure 2A), this drug was selected for more detailed studies. Treatment of cells for different periods of time with prazosin revealed that the maximum effect was achieved after 14–16 h incubation (results not shown). Following this initial characterization, we evaluated the effect of different concentrations of prazosin (Figure 2B). Prazosin increased cell surface FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP levels in a concentration-dependent manner, with the EC50 in the nanomolar range and a maximum effect at 10−7 M (Figure 2B). Although this concentration is more than 100-fold higher than the Kd for prazosin at the α1b-adrenoceptor measured in broken cell [3H]prazosin-binding studies, prazosin is not a highly membrane-permeant ligand, and the effective concentration reaching the receptor within the ER is likely to be much lower. Visualization of eYFP and anti-FLAG staining of cells, as in Figure 1, confirmed that treatment with prazosin resulted in cell surface delivery of FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP (Figure 2C) without altering the cellular distribution of wild-type FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. The α1-adrenoceptor antagonist prazosin promotes cell surface delivery of FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP.

(A) Intact cell anti-FLAG ELISA screening of the effect of several drugs known to have affinity for the α1b-adrenoceptor. ELISA assays were performed on cells stably expressing FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP after an overnight treatment with 10−5 M of each drug. Basal (−) staining reflects non-specific labelling of the cells. Statistics were performed using a one-way ANOVA with the application of the Tukey post-test analysis: *significantly greater than basal, +, significantly lower than the effect of prazosin, P<0.01 in each case. (B) Prazosin increases cell surface FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP in a concentration-dependent manner. Intact cell, anti-FLAG ELISA assays were performed as in (A) following overnight treatment with varying concentrations of prazosin. Results are expressed as mean of the fold increase of the absorbance detected in untreated cells (±S.E.M.). (C) Anti-FLAG immunocytochemistry (α-FLAG, red) was performed as in Figure 1 in fixed, non-permeabilized cells expressing either FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP (upper images) or FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP (lower images) that were treated overnight with 10−7 M prazosin. Imaging of eYFP (green) confirmed expression of both constructs and merging of the images (Merge) confirmed that prazosin treatment promoted cell surface delivery of FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP (lower panels, right-hand image). Blue staining represents nuclear staining with the DNA-binding dye Hoechst 33342.

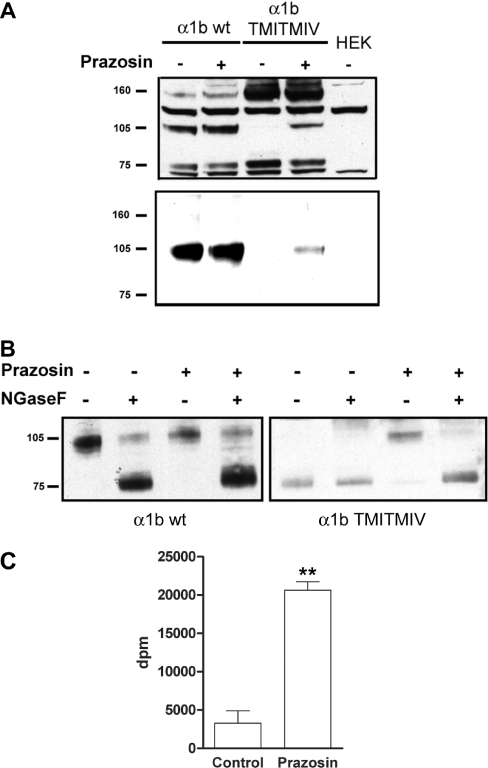

Only the mature, terminally N-glycosylated form of the α1b-adrenoceptor is delivered to the cell surface

Many GPCRs are produced as immature forms that require final terminal glycosylation prior to effective plasma membrane delivery [22,23]. Given the inability of FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP to reach the cell surface, we examined the potential existence of differences in the glycosylation pattern between the wild-type and the TMI-TMIV mutant α1b-adrenoceptor constructs. SDS/PAGE and anti-FLAG immunoblotting of lysates of cells expressing FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP indicated this construct could be detected as three predominant polypeptides of apparent masses corresponding to 75, 105 and 160 kDa (Figure 3A, upper panel). Two further polypeptides identified by the anti-FLAG antibodies were unrelated to the FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP polypeptide, as these were also detected in lysates of parental, non-transfected HEK-293 cells (Figure 3A). By contrast with FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP, the FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP mutant was present only as the 75 and 160 kDa forms (Figure 3A). We have previously demonstrated that, in transiently transfected cells, the 105 kDa form of FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP corresponds to the terminally N-glycosylated form of the receptor [18]. We confirmed that this was also the case in HEK-293 cells stably expressing FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP, because treatment of lysates from these cells with NGaseF resulted in loss of the 105 kDa band (Figure 3B) and its replacement by the form with an apparent mass of 75 kDa (Figure 3B), whereas treatment with EndoH did not alter the mobility of the 105 kDa band (results not shown). Furthermore, cell surface biotinylation assays demonstrated that the terminally N-glycosylated form of FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP was the only form present at the cell surface (Figure 3A, lower panel). Treatment of cells expressing FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP with prazosin (10−7 M, 16 h) had little effect on the glycoslyation pattern (Figure 3A, upper panel) or levels of cell surface FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP that could be detected via biotinylation (Figure 3A, lower panel). By contrast, equivalent treatment of cells expressing FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP with prazosin resulted in the appearance of the 105 kDa form (Figure 3A, upper panel), its detection as a cell surface biotinylated polypeptide (Figure 3A, lower panel) and the capacity of NGaseF to modify the 105kDa polypeptide form of FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP such that it now migrated as the 75 kDa species (Figure 3B). Intact cell [3H]prazosin binding studies of cells expressing FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP, pre-treated with prazosin and then extensively washed, also confirmed marked increases of cell surface FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP from almost undetectable levels (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. Only the terminally N-glycosylated form of the α1b-adrenoceptor reaches the cell surface.

(A) Upper panel: cell lysates of parental HEK-293 cells (HEK) and cells stably expressing either FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP (α1b wt) or FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP (α1b TMI-TMIV) that were treated with (+) or without (−) prazosin (10−7 M, 12 h) were resolved by SDS/PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-FLAG. Lower panel: cell surface biotinylation of the above cells. After treatment with or without prazosin, cell surface α1b-adrenoceptors were biotinylated and pulled down with streptavidin–agarose beads, resolved by SDS/PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-FLAG antibody. (B) Mock (−) or NGaseF de-glycosylation (+) followed by anti-FLAG immunoblotting of cell lysates of FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP (α1b wt) and FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP (α1b TMI-TMIV) cells that were treated with (+) or without (−) prazosin (10−7 M, 12 h) was performed to identify mature and immature forms of the receptor. (C) Intact cell-specific [3H]prazosin binding studies (0.4 nM final) were performed in cells stably expressing FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP that had previously been treated with or without 10−7 M prazosin for an overnight period and then extensively washed. **P<0.001 (Student's t test).

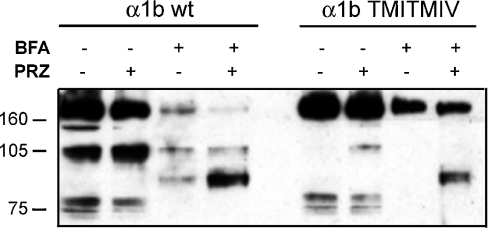

In order to assess more fully the cellular location of the pharmacological chaperone action of prazosin, cells were pre-treated with combinations of prazosin and BFA, a toxin that collapses the Golgi apparatus and therefore blocks the transport of proteins beyond the ER and on to the cell surface. Co-treatment of cells expressing FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP with prazosin and BFA resulted in the loss of appearance of the 105 kDa band corresponding to the terminally N-glycosylated cell surface form of the receptor (Figure 4). However, in cells expressing either wild-type or the mutant α1b-adrenoceptor constructs that had previously been treated with prazosin, BFA treatment resulted in the appearance of a distinct band with an apparent mass of 90 kDa (Figure 4) that is likely to correspond to a form of the receptor containing incompletely processed N-linked oligosaccharides. As such, prazosin acts at a point prior to the final production of the terminally N-glycosylated forms of the receptor in the Golgi and allows this step to occur.

Figure 4. BFA treatment prevents full N-glycosylation of the α1b-adrenoceptor.

Lysates of cells stably expressing either FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP (α1b wt) or FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP (α1b TMI-TMIV) that were treated with prazosin (PRZ) and/or Brefeldin A (BFA) as indicated (10−7 M and 5 μg/ml for 12 h respectively) were resolved by SDS/PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-FLAG.

Functional rescue of the FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV mutant

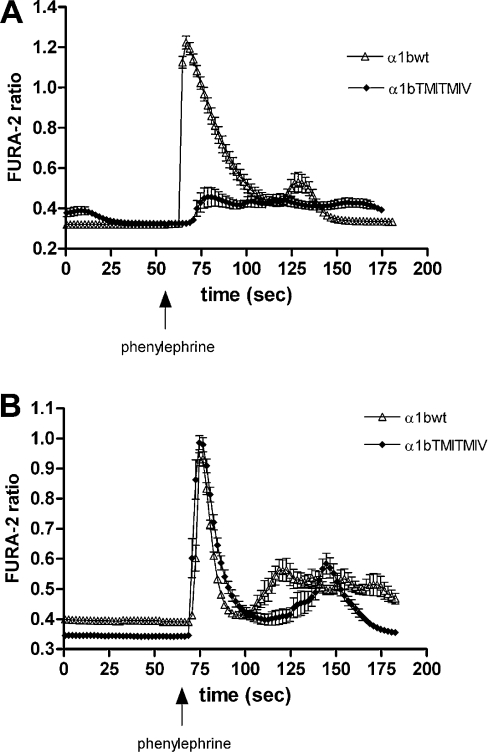

Our previous studies in transiently transfected HEK-293 cells demonstrated that the α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV mutant was unable to generate an intracellular Ca2+ mobilization signal [18]. It was unclear, however, if this reflected its absence from the plasma membrane or was inherently due to the introduced mutations. To assess this, we delivered the stably expressed FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP to the cell surface by pre-treatment with prazosin. However, the use of prazosin as a pharmacological chaperone for the rescue of FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP to the cell surface implies the occupancy of the receptor binding site by this antagonist. It was therefore necessary to remove the antagonist completely following its effect as a pharmacological chaperone to subsequently assess receptor functionality. We extensively washed the treated cells with fresh media in the absence of prazosin for at least 12 h. To assess the effectiveness of prazosin washout, saturation binding experiments with [3H]prazosin were then performed on membranes from prazosin-treated and untreated cells expressing either wild-type or the TMI-TMIV mutant FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP. Such saturation experiments indicated no differences in terms of Kd or Bmax for FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP (results not shown), suggesting that the prazosin used for the pre-treatment had been completely removed. Following optimization of the washout conditions, intracellular Ca2+ mobilization assays were performed in cells expressing FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP or FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP with and without prazosin pre-treatment. In cells that had not been pre-treated with prazosin, the α1-adrenoceptor agonist phenylephrine caused a transient elevation of intracellular [Ca2+] only in cells expressing FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP (Figure 5A). By contrast, in cells that had been pre-treated with prazosin, phenylephrine now resulted in elevation of intracellular [Ca2+] in cells expressing either FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP or FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Agonist-mediated elevation of calcium in cells expressing FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP is only observed following prazosin treatment.

Cells stably expressing FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP (Δ) or FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP (♦) were loaded with Fura-2 and stimulated with 10−5 M phenylephrine at the indicated time. (A) Untreated cells and (B) cells pre-treated with prazosin (10−7 M, 12 h). Alterations in Fura-2 fluorescence ratios report changes in intracellular Ca2+ levels. A representative of 3 independent experiments is shown.

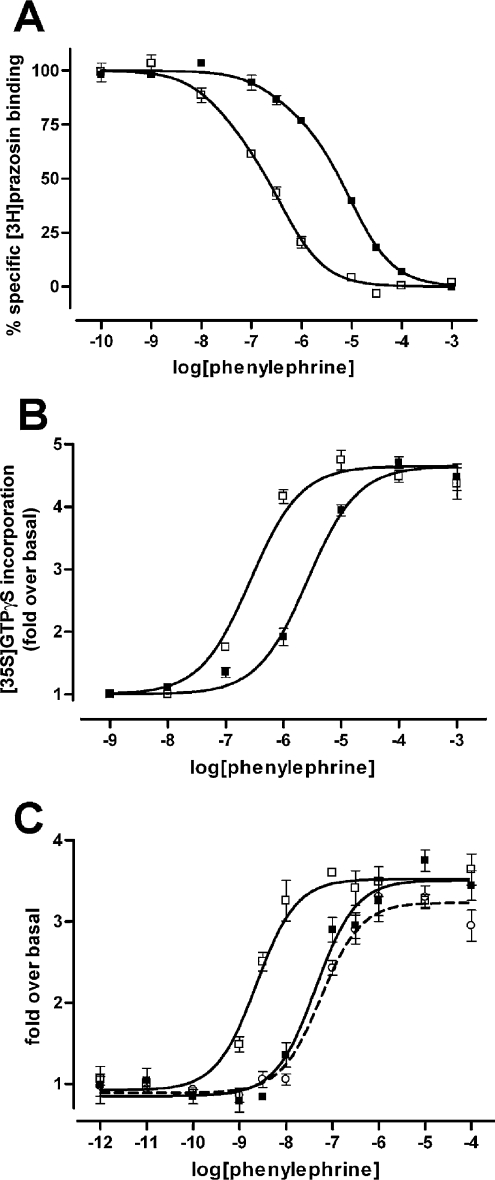

Pharmacological characterization of the α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV mutant

We recently reported, in transiently transfected cells, that, when compared with the wild-type α1b-adrenoceptor, FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP displays an atypical pharmacological profile. The mutant displayed significantly higher binding affinity for the agonist phenylephrine [18]. In agreement with the data in transiently transfected cells, in membrane preparations of HEK-293 cells stably expressing FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP, phenylephrine was significantly more potent in competing for the binding of [3H]prazosin than in membranes from cells expressing FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP (Figure 6A and Table 1). This higher affinity of phenylephrine for FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP was reflected in an equivalent augmentation of potency of this agonist in both Gαq/11 [35S]GTP[S] binding and intracellular Ca2+ mobilization assays. In both cases phenylephrine was approx. 10-fold more potent at the FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP mutant than at the FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP wild-type (Figures 6B and 6C, and Table 2). This was despite the intracellular Ca2+ mobilization experiments being performed in intact cells pre-treated with prazosin to facilitate receptor delivery to the cell surface, whereas the [35S]GTP[S] binding experiments were performed with total membranes from untreated cells. Of interest, the [35S]GTP[S] binding results demonstrate that FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP is able to couple to Gαq/11 G-proteins within the intracellular compartment(s) where it is retained and therefore is an immature protein. This is consistent with recent reports indicating that the β2-adrenoceptor becomes G-protein-associated prior to membrane delivery [24]. Although not explored exhaustively, this variation in agonist affinity/potency was not restricted to phenylephrine. For example, adrenaline also displayed higher affinity for FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP (pKi=7.2) than for FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP (pKi=6.3) in [3H]prazosin competition binding experiments.

Figure 6. Pharmacological comparisons of FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP and FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP.

(A) Ligand-binding characteristics of the wild-type and mutant α1b-adrenoceptor. The capacity of phenylephrine to compete for binding with [3H]prazosin to FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP (■) and FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP (□) was assessed. (B) Stimulation of [35S]GTP[S] binding by phenylephrine in Gαq/Gα11 immunoprecipitates from membranes of HEK-293 cells stably expressing FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP (■) and FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP (□). (C) Intracellular calcium mobilization induced by phenylephrine in cells stably expressing FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP (■) and FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP previously treated with 10−7 M prazosin (□). Complete removal of prazosin after the overnight period was assessed by testing the response of the wild-type receptor after treatment and washout (open circles). All graphs are representative results from at least three independent experiments.

Table 1. Binding affinity of phenylephrine is higher for FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP than for the wild-type receptor.

Membrane preparations of HEK-293 cells stably expressing either FLAG-α1b-eYFP or FLAG-α1b-TMI-TMIV-eYFP receptors and pre-treated or not with prazosin were used to perform [3H]prazosin/phenylephrine competition binding assays as described in the Experimental section. Values are means±S.E.M of the indicated number of independent experiments. Significant differences from FLAG-α1b-eYFP: *P<0.05; **P<0.001 (Student's t test)

| pKi (high) | pKi (low) | n | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FLAG-α1b-eYFP | 7.09±0.52 | 4.88±0.18 | 6 |

| FLAG-α1b-TMI-TMIV-eYFP | 8.64±0.17* | 6.33±0.17** | 12 |

| FLAG-α1b-TMI-TMIV-eYFP (prazosin treatment) | 9.09±0.42* | 5.90±0.20** | 5 |

Table 2. Phenylephrine has higher potency for activation of G-proteins and Ca2+ mobilization via FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP.

[35S]GTPγS: membrane preparations of HEK-293 cells stably expressing either FLAG-α1b-eYFP or FLAG-α1b-TMI-TMIV-eYFP receptors were used to perform [35S]GTPγS binding assays as described in the Experimental section. Ca2+ mobilization: HEK-293 cells stably expressing either FLAG-α1b-eYFP or FLAG-α1b-TMI-TMIV-eYFP receptors untreated or treated with prazosin (10−7 M, 16 h) were used to perform intracellular calcium mobilization assays using a FlexStation as described in the Experimental section. Values are means±S.E.M of three independent experiments. *P<0.05 (Student's t test).

| pEC50 | n | |

|---|---|---|

| [35S]GTPγS | ||

| FLAG-α1b-eYFP | 5.33±0.13 | 3 |

| FLAG-α1b-TMI-TMIV-eYFP | 6.45±0.8* | 3 |

| Ca2+ mobilization | ||

| FLAG-α1b-eYFP | 7.23±0.13 | 6 |

| FLAG-α1b-eYFP (prazosin treatment) | 7.02±0.12 | 6 |

| FLAG-α1b-TMI-TMIV-eYFP (prazosin treatment) | 8.45±0.14* | 4 |

To examine if such differences in affinity and potency of phenylephrine for FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP and FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP corresponded to differences in receptor glycosylation/maturation states, we initially performed [3H]prazosin/phenylephrine competition binding experiments using total cell membranes prepared from cells expressing FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP that were treated or not with the glycosylation inhibitor tunicamycin, membranes expressing FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP that were subjected to NGaseF treatment, or membranes from cells expressing FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP treated with prazosin. No differences in phenylephrine affinity were observed when the wild-type FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor-eYFP was not terminally N-glycosylated by either inhibiting de novo glycosylation with tunicamycin or deglycosylating the receptor with NGaseF (results not shown). Similarly, when FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP was encouraged to mature and become terminally N-glycosylated by prazosin treatment, no differences in phenylephrine binding parameters were observed either (Table 1). Together, all these results lead us to conclude that the atypical pharmacological profile of the mutant receptor for phenylephrine and other agonists is inherent to the mutations in TMI and TMIV rather than a consequence of defective maturation of the mutant receptor.

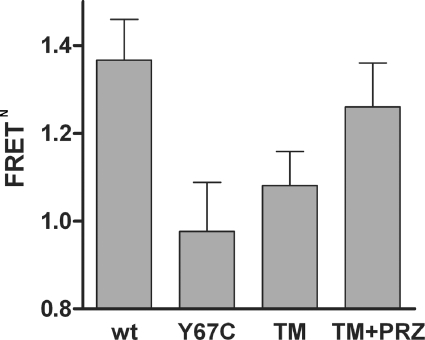

The conformational change induced by prazosin affects the oligomeric organization of the α1b-adrenoceptor

The TMI and TMIV mutations in the α1b-adrenoceptor result not only in defective receptor maturation and delivery to the plasma membrane, but also in alteration of quaternary structure, with the TMIV mutations being critical for this effect [18]. To assess if the rescue of cell surface expression produced by treatment with prazosin was associated with a change in conformation and/or the oligomeric organization of the receptor, we employed single cell 3-colour FRET imaging [18]. Forms of the FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV mutant C-terminally tagged with each of eCFP, eYFP and dsRed2 were transiently co-expressed in HEK-293 cells. Sequential eCFP to dsRed2 FRET was then measured following pre-treatment with prazosin or vehicle. Controls expressed FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV linked to Y67C-eYFP, a non-fluorescent variant of eYFP that therefore can act neither as a FRET acceptor from eCFP nor as a FRET donor to dsRed2, along with the eCFP and dsRed2 tagged forms of FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV. As described previously [18], differences in eCFP to dsRed2 FRET signals between cells co-expressing the receptor tagged with each of eCFP, eYFP and dsRed2 and cells co-expressing the receptor tagged with each of eCFP, Y67C-eYFP and dsRed2 represent the FRET that has been transferred sequentially from eCFP to eYFP and then to dsRed2, rather than directly from eCFP to dsRed2, and reports directly on the oligomeric organization of the receptor. The mutations in TMI and TMIV affected the quaternary structural organization of the α1b-adrenoceptor as shown by a marked decrease in sequential eCFP to eYFP to dsRed2 FRET signal compared with those produced following expression of the equivalent forms of the wild-type α1b-adrenoceptor (Figure 7). However, after treatment with prazosin of cells expressing the three FRET-competent forms of the FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV mutant, the sequential FRET signal (i.e. eCFP to dsRed2 FRET) was increased (Figure 7) and now was not significantly lower than the sequential FRET signal for the wild-type receptor. This probably reflects changes of conformation induced by prazosin which may induce modifications in orientation of or distances between, the FRET fluorophores and hence increase the energy transfer. These results provide a correlation between the effectiveness of cell surface delivery of the α1b-adrenoceptor and the prazosin-induced recovery of the quaternary structural organization of FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV.

Figure 7. Sequential 3-colour FRET imaging demonstrates that prazosin binding alters the oligomeric structure of the FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV mutant.

C-terminally eCFP, eYFP, and dsRed2 forms of FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor (wt) or FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV (TM) were co-expressed in HEK-293 cells and eCFP to dsRed2 FRET was measured as detailed in Lopez-Gimenez et al. [18]. In experiments involving FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV, controls were provided by replacing the eYFP-tagged construct with the equivalent construct tagged with Y67C eYFP (Y67C) which is not fluorescent and hence acts as neither a FRET energy acceptor (from eCFP) nor donor (to dsRed2). FRET data are reported as normalized FRET (FRETN) as described by Lopez-Gimenez et al. [18]. In this context FRETN=1.0 represents an absence of energy transfer (and is the anticipated value when employing Y67C eYFP). FRETN values greater than 1.0 reflect the occurrence of sequential FRET. In a number of experiments, cells expressing the eCFP, eYFP and dsRed2 forms of FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV were treated with prazosin (10−7 M, 12 h) (TM+PRZ) prior to measurement of FRET signals.

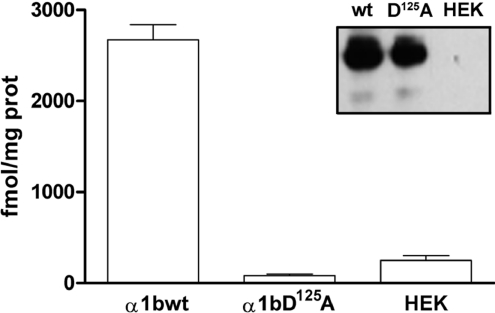

The α1b-adrenoceptor is delivered to the cell surface as a dimer/oligomer

The α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV mutant receptor acts as a dominant-negative for the wild-type α1b-adrenoceptor by limiting its cell surface expression when both forms are co-expressed [18]. We therefore assessed if the pharmacological chaperone action of prazosin on α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV would concurrently traffic co-expressed, and hence ER-retained, wild-type α1b-adrenoceptor to the plasma membrane as part of a dimeric/oligomeric complex with α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV. To perform these studies we generated a form of Myc-α1b-adrenoceptor-Y67C-eYFP that is unable to bind prazosin due to introduction of a D125A (D3.32A) mutation into the receptor [25] (Figure 8). Although unable to bind prazosin with significant affinity, Myc-D125Aα1b-adrenoceptor-Y67C-eYFP was expressed to similar levels as Myc-α1b-adrenoceptor-Y67C-eYFP (Figure 8). Myc-D125Aα1b-adrenoceptor-Y67C-eYFP was delivered to the surface of HEK-293 cells when expressed alone (Figure 9), but was trapped intracellularly when co-expressed with FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP (Figure 9). Treatment of cells co-expressing Myc-D125Aα1b-adrenoceptor-Y67C-eYFP and FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP with prazosin resulted in delivery of both FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP and Myc-D125Aα1b-adrenoceptor-Y67C-eYFP to the cell surface (Figure 9), despite Myc-D125Aα1b-adrenoceptor-Y67C-eYFP being unable to bind prazosin. This is consistent with the ligand allowing cell surface trafficking of a dimer/oligomer containing copies of both FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP and Myc-D125Aα1b-adrenoceptor-Y67C-eYFP.

Figure 8. Myc-D125Aα1b-adrenoceptor-Y67C-eYFP is well expressed but does not bind [3H]prazosin with significant affinity.

Membranes from mock transfected (HEK) HEK-293 cells and cells transfected to express Myc-α1b-adrenoceptor-Y67C-eYFP (α1bwt) or Myc-D125Aα1b-adrenoceptor-Y67C-eYFP (α1bD125A) were employed in specific [3H]prazosin (10 nM) binding studies. Inset: membranes of these cells were resolved by SDS/PAGE and immunoblotted to detect the Myc epitope.

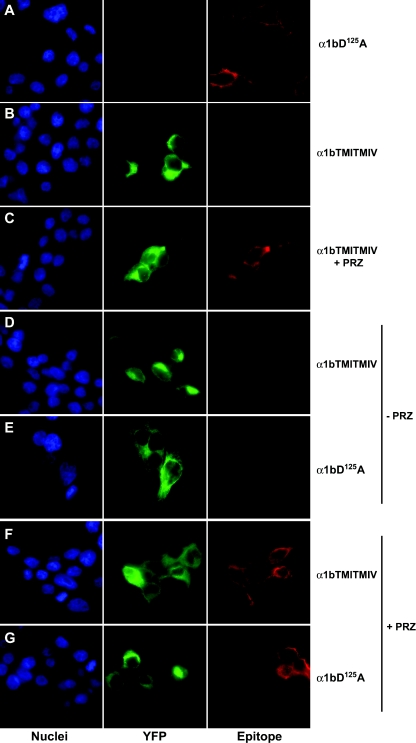

Figure 9. Prazosin-induced cell surface delivery of FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP also recovers co-expressed and ER-trapped Myc-D125Aα1b-adrenoceptor-Y67C-eYFP to the cell surface.

HEK-293 cells were transfected to express Myc-D125Aα1b-adrenoceptor-Y67C-eYFP (α1bD125A, A), FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP (α1bTMITMIV, B and C), or both Myc-D125Aα1b-adrenoceptor-Y67C-eYFP and FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP in a 1:3 ratio (D–G). Immunocytochemistry (Epitope) was performed on non-permeabilized cells using either anti-Myc (A, E and G) or anti-FLAG (B–D and F) antibodies and a secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa594 (red) whilst monitoring eYFP (YFP, green) provided a measure of FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP expression and distribution. Nuclei were identified with Hoechst 33342 nuclear dye (blue). Co-expression of FLAG-α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV-eYFP with Myc-D125Aα1b-adrenoceptor-Y67C-eYFP resulted in intracellular retention of the D125A version of the receptor (E). After prazosin (PRZ) treatment (10−7 M, overnight), both N-terminal epitopes were detected at the cell surface (F and G).

DISCUSSION

The results reported herein provide novel evidence on the capacity of the α1b-adrenoceptor to dimerize/oligomerize in the ER and to traffic to the cell surface as a quaternary complex. Supporting previous studies in which mutations in TMI and TMIV of the α1b-adrenoceptor resulted in both alteration of receptor quaternary structure and intracellular retention [18], we now demonstrate that the ability of α1-adrenoceptor antagonists to act as pharmacological chaperones and recover the α1b-adrenoceptor TMI-TMIV mutant to the cell surface is correlated with the ability of the ligands to produce conformational changes that alter the quaternary structure of the mutant receptor to a form that resembles the wild-type. The binding of such ligands also promoted the correct series of steps in terminal N-glycosylation and maturation to allow cell surface delivery of the mutant α1b-adrenoceptor. However, it remains uncertain if these two effects (i.e. generation of the correct quaternary structure and receptor maturation) are linked causally or, if so, which is the initial event. Synthesis of GPCRs in the ER, as for other proteins, is a tightly regulated process. This concludes with a correctly folded polypeptide which, after further maturation steps in the Golgi, is trafficked to the cell surface. The ER is the main organelle of quality control over mis-folded unstable proteins and therefore functions to prevent the transport and delivery of potentially non-functional units. Protein folding is a highly complex process that requires interactions of newly synthesized proteins with ER-residing chaperones. Proteins that fail to undergo correct folding are eventually routed for proteosomal degradation. Mutations that affect folding and surface delivery have been described for a number of GPCRs and pathological states (see [13,17] for reviews). Small molecule GPCR ligands able to enter cells and bind to and assist with folding and subsequent plasma membrane delivery of mutant GPCRs are described as pharmacological chaperones. Here we also report that an oligomerization-defective α1b-adrenoceptor mutant can be trafficked from the ER to the cell surface by the antagonist prazosin.

Mutant GPCRs that are retained in the ER are often able to act as dominant-negatives for cell surface delivery of the wild-type form of the same receptor. This could reflect major folding defects that result in the exposure of inappropriate domains and, hence, cause non-specific protein aggregation. However, rather than being severely mis-folded and hence unable to bind α1-adrenoceptor ligands, the mutant that we have generated binds antagonist ligands with ‘wild-type’ affinity and actually binds agonist ligands with higher affinity than the wild-type α1b-adrenoceptor. Furthermore, we have previously shown that this mutant does not interfere with the cell surface trafficking of all co-expressed GPCRs [18], indicating that the relevant effect is a selective one. This provides clear evidence that the dominant-negative effect of the mutant α1b-adrenoceptor on the co-expressed wild-type α1b-adrenoceptor truly reflects the formation of ER-retained dimers/oligomers. Because prazosin treatment of cells expressing the mutant receptor concurrently allowed a co-expressed, otherwise wild-type, α1b-adrenoceptor that is unable to bind ligand to reach the cell surface, this indicates that the mature α1b-adrenoceptor must traffic to the cell surface as a dimeric/oligomeric complex. Increased cell surface expression of the mutant receptor could also potentially have been a consequence of antagonist-mediated stabilization of immature forms of the mutant receptor that might saturate the ER quality control system and hence result in trafficking to the cell surface. However, the differential N-glycosylation pattern following prazosin treatment allowed us to eliminate this possibility. As the inability of a receptor to reach the cell surface often limits its response to agonists, it is logical to think that once it reaches the plasma membrane it may recover its functionality [26]. In the case of the α1b-adrenoceptor mutant, we demonstrated that the lack of receptor at the plasma membrane was the cause of the absence of response to agonist, because when the mutant, which actually, although unexpectedly, binds agonist ligands with higher affinity than the wild-type receptor, was recovered to the cell surface by prazosin treatment, receptor response was also restored and with potency for agonist ligands higher than for the wild-type receptor.

Although the current data on the α1b-adrenoceptor provide strong evidence of the dimeric/oligomeric nature of the cell-surface-delivered forms of this GPCR, it remains to be established if this is universally true. For example, although a number of studies have previously indicated GPCR dimerization to occur prior to plasma membrane delivery [4,19,27], a number of other studies have suggested that this is not inherently required and that dimerization-deficient GPCRs and GPCR monomers can reach the cell surface [28,29]. It remains possible that there are variations in the mechanisms of trafficking of different members of the GPCR superfamily and, if so, it will be important to understand the general rules that govern this process.

Studies exploring the contribution of TMs to the interactions that generate GPCR quaternary structure have produced conflicting data (see [2] for review). Indeed, detailed analysis of the literature provides evidence for contributions of all TMs, apart from TMIII, in various GPCRs. Furthermore, in a number of studies contributions of multiple TMs were implicated [30,31]. Such data potentially provide support for GPCRs existing as more complex oligomeric structures rather than simple dimers. However, in recent times, a series of studies have concentrated attention on the importance of TMIV as a dimeric/oligomeric interface for rhodopsin family GPCRs [2]. Most importantly for the present study, Guo et al. [32] replaced residues all along TMIV of the dopamine D2 receptor with cysteines and then performed cross-linking experiments in the presence of agonist or inverse agonist ligands. Differences in the rate of cross-linking of individual sites were consistent with the binding of antagonist/inverse agonists (as well as agonists) altering the detailed structure of TMIV and with the concept of ligand binding being communicated between protomers across the dimer/oligomer interface [32]. A number of studies have also attempted to interfere with GPCR dimerization by targeting TMIV. One strategy has been to employ peptides corresponding to specific TMs. Wang et al. [33] demonstrated that a synthetic peptide corresponding to TMIV of the chemokine CXCR4 receptor reduced FRET signals between co-expressed energy-transfer competent forms of this receptor and blocked a number of CXCR4-mediated effects. The contribution of individual amino acids within transmembrane helices to GPCR dimerization has, however, been difficult to explore or to generalize. Our selection of amino acids in TMIV and in TMI was based on the self-association of receptor fragments containing these elements [30] and on the informatic and biochemical experiments of Hernanz-Falcon et al. [28] on the potential interface(s) of the chemokine CCR5 receptor dimer/oligomer.

In conclusion, by employing a α1b-adrenoceptor mutant that has altered quaternary structure and is retained in the ER, we provide clear evidence that effective dimerization/oligomerization is required to allow a GPCR to pass protein quality control in the ER and demonstrate that pharmacological chaperones can alter the defective quaternary organization of a GPCR mutant to ensure correct processing and cell surface delivery of a ER pre-assembled dimeric/oligomeric complex of the α1b-adrenoceptor.

FUNDING

These studies were supported by the Medical Research Council [grant number G9811527] and the Wellcome Trust [grant number AL 070185 MA].

References

- 1.Milligan G. G protein-coupled receptor dimerization: function and ligand pharmacology. Mol. Pharmacol. 2004;66:1–7. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.000497.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Milligan G. G protein-coupled receptor dimerisation: molecular basis and relevance to function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2007;1768:825–835. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fotiadis D., Jastrzebska B., Philippsen A., Muller D. J., Palczewski K., Engel A. Structure of the rhodopsin dimer: a working model for G-protein-coupled receptors. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2006;16:252–259. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bulenger S., Marullo S., Bouvier M. Emerging role of homo- and heterodimerization in G-protein-coupled receptor biosynthesis and maturation. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2005;26:131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Terrillon S., Bouvier M. Roles of G-protein-coupled receptor dimerization. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:30–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brothers S. P., Cornea A., Janovick J. A., Conn P. M. Human loss-of-function gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor mutants retain wild-type receptors in the endoplasmic reticulum: molecular basis of the dominant-negative effect. Mol. Endocrinol. 2004;18:1787–1797. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calebiro D., de Filippis T., Lucchi S., Covino C., Panigone S., Beck-Peccoz P., Dunlap D., Persani L. Intracellular entrapment of wild-type TSH receptor by oligomerization with mutants linked to dominant TSH resistance. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005;14:2991–3002. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marshall F. H., Jones K. A., Kaupmann K., Bettler B. GABAB receptors – the first 7TM heterodimers. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1999;20:396–399. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01383-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Margeta-Mitrovic M., Jan Y. N., Jan L. Y. A trafficking checkpoint controls GABA(B) receptor heterodimerization. Neuron. 2000;27:97–106. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsukaguchi H., Matsubara H., Taketani S., Mori Y., Seido T., Inada M. Binding-, intracellular transport-, and biosynthesis-defective mutants of vasopressin type 2 receptor in patients with X-linked nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. J. Clin. Invest. 1995;96:2043–2050. doi: 10.1172/JCI118252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Illing M. E., Rajan R. S., Bence N. F., Kopito R. R. A rhodopsin mutant linked to autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa is prone to aggregate and interacts with the ubiquitin proteasome system. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:34150–34160. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204955200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leanos-Miranda A., Ulloa-Aguirre A., Janovick J. A., Conn P. M. In vitro coexpression and pharmacological rescue of mutant gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptors causing hypogonadotropic hypogonadism in humans expressing compound heterozygous alleles. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005;90:3001–3008. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernier V., Lagace M., Bichet D. G., Bouvier M. Pharmacological chaperones: potential treatment for conformational diseases. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2004;15:222–228. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernier V., Morello J. P., Zarruk A., Debrand N., Salahpour A., Lonergan M., Arthus M. F., Laperriere A., Brouard R., Bouvier M., Bichet D. G. Pharmacologic chaperones as a potential treatment for X-linked nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006;17:232–243. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005080854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morello J. P., Petaja-Repo U. E., Bichet D. G., Bouvier M. Pharmacological chaperones: a new twist on receptor folding. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2000;21:466–469. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01575-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morello J. P., Salahpour A., Laperriere A., Bernier V., Arthus M. F., Lonergan M., Petaja-Repo U., Angers S., Morin D., Bichet D. G., Bouvier M. Pharmacological chaperones rescue cell-surface expression and function of misfolded V2 vasopressin receptor mutants. J. Clin. Invest. 2000;105:887–895. doi: 10.1172/JCI8688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ulloa-Aguirre A., Janovick J. A., Brothers S. P., Conn P. M. Pharmacologic rescue of conformationally-defective proteins: implications for the treatment of human disease. Traffic. 2004;5:821–837. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2004.00232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lopez-Gimenez J. F., Canals M., Pediani J. D., Milligan G. The α1b-adrenoceptor exists as a higher-order oligomer: effective oligomerization is required for receptor maturation, surface delivery, and function. Mol. Pharmacol. 2007;71:1015–1029. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.033035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salahpour A., Angers S., Mercier J. F., Lagace M., Marullo S., Bouvier M. Homodimerization of the β2-adrenergic receptor as a prerequisite for cell surface targeting. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:33390–33397. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403363200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ballesteros J W. H. Integrated methods for the construction of 3-dimensional models and computational probing of structure relations in G protein-coupled receptors. Methods Neurosci. 1995;25:366–428. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitchell F. M., Mullaney I., Godfrey P. P., Arkinstall S. J., Wakelam M. J., Milligan G. Widespread distribution of Gq α/G11 α detected immunologically by an antipeptide antiserum directed against the predicted C-terminal decapeptide. FEBS Lett. 1991;287:171–174. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Conn P. M., Knollman P. E., Brothers S. P., Janovick J. A. Protein folding as posttranslational regulation: evolution of a mechanism for controlled plasma membrane expression of a G protein-coupled receptor. Mol. Endocrinol. 2006;20:3035–3041. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petaja-Repo U. E., Hogue M., Laperriere A., Walker P., Bouvier M. Export from the endoplasmic reticulum represents the limiting step in the maturation and cell surface expression of the human δ opioid receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:13727–13736. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.18.13727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dupre D. J., Robitaille M., Ethier N., Villeneuve L. R., Mamarbachi A. M., Hebert T. E. Seven transmembrane receptor core signaling complexes are assembled prior to plasma membrane trafficking. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:34561–34573. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605012200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cavalli A., Fanelli F., Taddei C., De Benedetti P. G., Cotecchia S. Amino acids of the α1B-adrenergic receptor involved in agonist binding: differences in docking catecholamines to receptor subtypes. FEBS Lett. 1996;399:9–13. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01286-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fan J., Perry S. J., Gao Y., Schwarz D. A., Maki R. A. A point mutation in the human melanin concentrating hormone receptor 1 reveals an important domain for cellular trafficking. Mol. Endocrinol. 2005;19:2579–2590. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilson S., Wilkinson G., Milligan G. The CXCR1 and CXCR2 receptors form constitutive homo- and heterodimers selectively and with equal apparent affinities. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:28663–28674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413475200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hernanz-Falcon P., Rodriguez-Frade J. M., Serrano A., Juan D., del Sol A., Soriano S. F., Roncal F., Gomez L., Valencia A., Martinez A. C., Mellado M. Identification of amino acid residues crucial for chemokine receptor dimerization. Nat. Immunol. 2004;5:216–223. doi: 10.1038/ni1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Law P. Y., Erickson-Herbrandson L. J., Zha Q. Q., Solberg J., Chu J., Sarre A., Loh H. H. Heterodimerization of μ- and δ-opioid receptors occurs at the cell surface only and requires receptor-G protein interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:11152–11164. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500171200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carrillo J. J., Lopez-Gimenez J. F., Milligan G. Multiple interactions between transmembrane helices generate the oligomeric α1b-adrenoceptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 2004;66:1123–1137. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.001586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klco J. M., Lassere T. B., Baranski T. J. C5a receptor oligomerization. I. Disulfide trapping reveals oligomers and potential contact surfaces in a G protein-coupled receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:35345–35353. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305606200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guo W., Shi L., Filizola M., Weinstein H., Javitch J. A. Crosstalk in G protein-coupled receptors: changes at the transmembrane homodimer interface determine activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:17495–17500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508950102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang J., He L., Combs C. A., Roderiquez G., Norcross M. A. Dimerization of CXCR4 in living malignant cells: control of cell migration by a synthetic peptide that reduces homologous CXCR4 interactions. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2006;5:2474–2483. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]