The AHR,2 a ligand-activated transcription factor, was first identified indirectly in the 1970s; the mouse and human genes were cloned in the early 1990s. Molecular mechanisms and biological consequences of AHR-mediated regulation of mammalian cytochrome P450 enzymes by foreign chemicals (e.g. polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and dioxins) have been studied extensively. Binding of such ligands to AHR leads to transcriptional activation of CYP1A1, CYP1A2, and CYP1B1; in turn, these enzymes catalyze oxidative detoxication or activation of most ligands. From the start, AHR endogenous ligands and functions were postulated; although this was initially controversial, the robust phenotype of Ahr–/– knock-out mice provided clear evidence of physiological roles (and endogenous ligands) for AHR. AHR has numerous important endogenous functions: during conception and embryonic and fetal development; in the immune, cardiovascular, neural, and reproductive systems; and in hepatocytes, skin cells, and adipocytes. These myriad AHR-mediated processes mirror the vast universe of action of the eicosanoids, lipid mediators known to undergo cytochrome P450-dependent oxidation. We propose that many endogenous and exogenous cellular stimuli lead to (i) AHR-dependent CYP1-dependent eicosanoid synthesis and degradation and (ii) AHR-dependent CYP1-independent (eicosanoid-dependent and -independent) responses. These two pathways can be delineated from one another in genetic models: the former is absent in the recently characterized Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1–/– triple-knock-out mouse, and the latter is absent in the Ahr–/– knock-out mouse. Identification of specific eicosanoids whose synthesis or degradation is carried out by each CYP1 enzyme should allow for identification of physiological endogenous AHR ligands. (For “History and Background,” see supplemental material (Box 1).)

Eicosanoids: Underappreciated Mediators of Everything

Oxygenated fatty acids are widely employed as signaling molecules by prokaryotes and eukaryotes (1). Among these, the eicosanoids are bioactive oxygenated derivatives of ω-6 or ω-3 essential fatty acids. Although the first identified eicosanoids were derived from fatty acids with 20 carbon atoms (hence, “eicosa,” Greek for “twenty”), such as arachidonic acid, eicosapentaenoic acid, and dihomo-γ-linolenic acid, related derivatives of 22-carbon atom essential fatty acids (e.g. docosahexaenoic acid) carry the same moniker.

Eicosanoids are local hormones released by most vertebrate (and some invertebrate) cells, which act in autocrine or paracrine fashion and then become rapidly inactivated. Potent in the nanomolar range, at least 13 categories of eicosanoids have been classified to date (supplemental Table S2), and if one includes all possible stereoisomers, the total number of eicosanoids now exceeds 150. Supplemental Table S2 lists the incredibly large number of critical life functions mediated via eicosanoids, showing some degree of specificity of function among the 13 categories. In terms of immunity, both initiation and resolution of inflammatory processes are under the critical control of eicosanoids (2).

Generally, eicosanoids are not stored within cells but are synthesized as needed; one exception is that red blood cells are reservoirs for cis- and trans-epoxyeicosatrienoic acids that can quickly be released (3). Stimuli that initiate eicosanoid biosynthesis and release include mechanical trauma, cytokines, growth factors, xenobiotics, and even other eicosanoids. Such stimuli trigger the activation of phospholipases at the cell or nuclear membrane, where fatty acid precursors of eicosanoids are incorporated as esters into larger molecules (phospholipids and diacylglycerol), whereupon the phospholipase catalyzes ester hydrolysis of phospholipid (via phospholipase A2) or diacylglycerol (via diacylglycerol lipase). The rate-limiting step for eicosanoid formation appears to be this hydrolysis, which frees eicosanoid precursors.

Do AHR-dependent CYP1-dependent Responses Reflect Eicosanoid Metabolism?

Eicosanoids exert complex control over virtually all life functions (supplemental Table S2). Interestingly, the list of processes that exhibit abnormalities when AHR is absent or are modulated by activation of AHR (supplemental Table S1) is quite similar to the list of eicosanoid-mediated functions (supplemental Table S2).

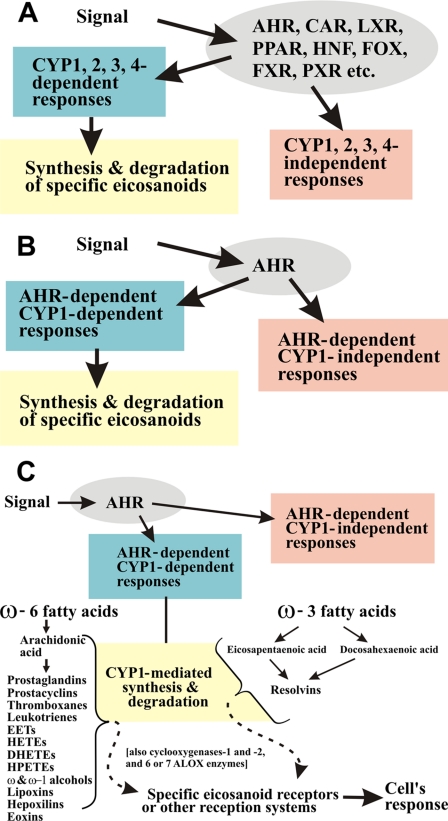

Generic Signals and Responses—Any of thousands of different exogenous signals affecting a cell can be viewed as a stimulus that is “perceived” by XTFs; these include the AHR, constitutive androstane receptor, hepatocyte nuclear factor, forkhead box, liver X receptor, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor, farnesoid X receptor, pregnane X receptor, and related families (Fig. 1A), which then regulate various downstream targets. The concept of xenobiotic-related transporters and XTFs has been recently reviewed (4). We envision the downstream events to include CYP1-, CYP2-, CYP3-, and CYP4-mediated synthesis and degradation of specific eicosanoids (5) as well as responses that are independent of these enzymes (Fig. 1A).

FIGURE 1.

A, relationship among XTFs; CYP1-, CYP2-, CYP3-, and CYP4-mediated eicosanoid metabolism; and CYP-mediated responses independent of eicosanoid metabolism. CAR (NR1I3), constitutive androstane receptor; LXR (NR1H), liver X receptor; PPAR (NR1C), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor; HNF (NR2A), hepatocyte nuclear factor; FOX, forkhead box; FXR (NR1H4), farnesoid X receptor; PXR (NR1I2), pregnane X receptor. B, relationship among specifically the AHR, CYP1-mediated eicosanoid metabolism, and AHR-mediated CYP1-independent responses. There are several CYP genes outside the CYP1 family that are regulated, at least in part, by AHR. There are AHR-dependent CYP1-independent eicosanoid-dependent pathways because of CYP2-, CYP3-, or CYP4-mediated metabolism of eicosanoids. C, subset of the diagram in B in which we illustrate CYP1-mediated versus ALOX-mediated metabolism of the 11 ω-6 fatty acid-derived and the four ω-3 fatty acid-derived categories of eicosanoids. Dihomo-γ-linolenic acid is usually considered as an additional separate series of eicosanoids; it is a C20:3 fatty acid (precursor to prostaglandins of the “1 series” such as prostaglandin E1) that is increased in ungulates (e.g. very high in sheep testicle) yet exists only in trace amounts in humans. In addition to six arachidonate lipoxygenase genes, ALOX5, ALOX12, ALOX12B, ALOX15, ALOX15B, and ALOXE3, which are orthologous between the human and mouse genomes, the mouse genome has a seventh gene, Alox12a. EETs, epoxyeicosatrienoic acids; HETEs, hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids; DHETEs, dihydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids; HPETEs, hydroperoxyepoxyeicosatrienoic acids.

AHR Signaling and Responses—Although AHR binds to AHR response elements in hundreds of genes throughout the genome, the three CYP1 genes conserved in all mammals (CYP1A1, CYP1A2, and CYP1B1) are both among the most highly induced of the panel of AHR-activated genes and central to the oxidative metabolism of many AHR ligands. Hence, we envision that signals received by AHR lead to downstream events (Fig. 1, B and C), which include AHR-dependent CYP1-dependent synthesis and degradation of specific eicosanoids and AHR-dependent CYP1-independent (eicosanoid-dependent and -independent) responses.

Cyclooxygenases and ALOXs—Although considerable emphasis has been placed on the role of cyclooxygenase-1 and -2 and the ALOXs in eicosanoid synthesis and degradation (Fig. 1C), it has been experimentally demonstrated that dozens of members of the CYP1, CYP2, CYP3, and CYP4 families also participate in these processes (Table 1) (5). Every member of these four CYP families might be involved in eicosanoid metabolism, perhaps with redundancy (5). Pursuant to the present review about AHR endogenous functions, the precise steps catalyzed by CYP1A1, CYP1A2, and CYP1B1 remain to be demonstrated. In fact, the large number, complexity of pathways, extreme lability, and similarity of the various eicosanoid chemical structures and stereoisomers all contribute to the difficulty of successful research in this arena.

TABLE 1.

Specific catalytic evidence for eicosanoid metabolism by members of the vertebrate CYP1, CYP2, CYP3, and CYP4 families

This search is not intended to be all inclusive but merely to illustrate the breadth of work in this field. The early pioneering work of Michal Laniado-Schwartzman, Volker Ullrich, Jorge Capdevila, Yoshihiko Funae, and Seiichi Yoshida is especially notable. The studies cited here were selected mostly on the basis of purified or recombinant cytochrome P450 protein. Even Xenopus oocytes exhibit P450-mediated formation of hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids (70). Interestingly, CYP-mediated metabolism of eicosapentaenoic acid in Caenorhabditis elegans has also been reported (71); this P450 is most closely related to the CYP4 family (D. R. Nelson, personal communication). ALOX enzymes also exist in prokaryotes (72) and protists (73). EETs, epoxyeicosatrienoic acids; HETEs, hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids; HPETEs, hydroperoxyepoxyeicosatrienoic acids.

| CYP subfamily and eicosanoid categories | Ref. |

|---|---|

| CYP1A | |

| Prostaglandins | 30, 33 |

| Arachidonic acid, prostaglandins | 31 |

| EETs, HETEs | 32, 35 |

| Arachidonic acid, EETs, eicosapentaenoic acid | 34 |

| Eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids | 36 |

| CYP1B | |

| EETs, HETEs | 37 |

| CYP2A | |

| Arachidonic acid, prostaglandins | 31 |

| CYP2B | |

| Arachidonic acid, prostaglandins | 31 |

| HPETEs | 38 |

| EETs, HETEs | 39 |

| EETs | 40, 41 |

| CYP2C | |

| Arachidonic acid, prostaglandins | 31 |

| Arachidonic acid | 42 |

| EETs, HETEs | 32 |

| Prostaglandins | 43 |

| EETs | 44 |

| CYP2D | |

| Arachidonic acid, HETEs | 45, 46 |

| CYP2E | |

| Arachidonic acid, prostaglandins | 31 |

| Arachidonic acid, EETs, HETEs | 47 |

| EETs, HETEs | 32 |

| Prostaglandins | 33 |

| CYP2J | |

| EETs | 48, 51 |

| Arachidonic acid, HETEs | 49 |

| Arachidonic acid | 50 |

| CYP2P | |

| Arachidonic acid, EETs, HETEs | 52 |

| CYP2U | |

| Arachidonic acid | 53 |

| CYP2W | |

| Arachidonic acid | 54 |

| CYP3A | |

| Arachidonic acid, prostaglandins | 31 |

| Prostaglandins | 33 |

| CYP4A | |

| Prostaglandins | 43, 55 |

| Prostaglandins, arachidonic acid | 56 |

| EETs | 11 |

| HETEs | 57 |

| CYP4B | |

| HETEs | 58, 59 |

| CYP4F | |

| Leukotrienes, prostaglandins | 60 |

| Leukotrienes | 61 |

| Prostaglandins | 43, 62, 63 |

| Arachidonic acid | 64 |

| Leukotrienes, lipoxins, HETEs | 65 |

| EETs | 66 |

| Eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids | 67 |

| Lipoxins, HETEs | 68 |

| HETEs | 69 |

Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1–/– Triple-knock-out Mouse as a Model System

How might AHR-dependent CYP1-dependent responses be dissected from AHR-dependent CYP1-independent responses (Fig. 1)? One excellent model system is the recently characterized Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1–/– triple-knock-out mouse (6). The other model system is the Ahr–/– knock-out mouse (reviewed in Refs. 7–9). Whereas Ahr–/– mice have no functional AHR, and therefore, all downstream genes regulated by the AHR should be affected, Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1–/– mice have a functional AHR but lack all three CYP1 enzymes. Therefore, using these two mouse lines, one should now be able to distinguish (in the intact mouse) between all AHR-dependent functions versus the subset of AHR-regulated CYP1-dependent functions.

Phenotype of the Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1–/– Mouse—When compared with wild-type mice (with incomplete penetrance), the Cyp1 triple-knock-out F1 mouse exhibited (i) infertility and embryo lethality, (ii) a significantly increased risk of certain birth defects (hydrocephalus, hermaphroditism, and cystic ovaries), and (iii) at least 89 genes significantly up-regulated versus 62 genes down-regulated (6). All of these phenotypes probably reflect deficiencies in cell proliferation and migration, ion transport, angiogenesis, and/or vascular pO2 sensing, again most likely eicosanoid-related processes (supplemental Table S2). Please see supplemental material (Box 2).

Dysregulation of the Inflammatory Response—Finally, an exaggerated response to zymosan-induced peritonitis, along with significant down-regulation of hepatic expression of the Socs2 (suppression of cytokine signaling-2) gene, was seen in Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1–/– mice (6). Both endogenous and exogenous AHR ligands are known to up-regulate SOCS2 expression. 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin has been shown to up-regulate SOCS2 expression in lymphocytes in an AHR-dependent fashion (10). Inhibition of dendritic cell production of pro-inflammatory cytokines by the pro-resolution lipoxin eicosanoids is dependent on AHR-driven up-regulation of SOCS2 expression (11). Activation of AHR by both native and aspirin-induced lipoxins triggers SOCS expression; this then leads to ubiquitinylation and proteasomal degradation of TRAF (tumor necrosis factor-α receptor-associated factor)-6 and TRAF-2, key adaptor molecules that couple interleukin-1/Toll-like and tumor necrosis factor receptor family members to intracellular signaling cascades (12). The decreased SOCS2 expression observed in the triple knock-out is consistent with a potential mechanism for the exaggerated zymosan-induced inflammatory response as well as the possibility that one or more of the AHR-regulated CYP1 enzymes participate in generation of endogenous eicosanoid ligands for AHR.

The Ahr–/– knock-out mouse shows a PDV and other AV shunt problems (13), along with immune dysregulation (14) and increased susceptibility to infection (15). The latter two traits were found in Cyp1a1/1a2/1b1–/– mice (6). Unless the Cyp1 triple knock-out is subsequently found also to include PDV and AV shunts, these findings suggest that one or more of the CYP1 enzymes participate in immune dysregulation and enhanced susceptibility to infection, whereas an AHR-dependent CYP1-independent process is responsible for increased risk of the PDV and AV shunts.

What Are the “True” Endogenous Ligands for AHR?

Various classes of endogenous compounds shown to induce CYP1 and/or activate AHR include (a) tryptophan metabolites, other indole-containing molecules, and phenylethylamines (16); (b) tetrapyrroles such as bilirubin and biliverdin; (c) sterols such as 7-ketocholesterol and the horse steroid equilenin; (d) fatty acid metabolites, including at least six different prostaglandins (17) and lipoxin A4; and (e) the ubiquitous second messenger cAMP (reviewed in Refs. 9 and 18). The dose of such putative inducers in the intact animal, the concentrations needed in cell cultures, and the dissociation constant of binding (Kd) for the majority of these candidates are, however, usually not as low as one would expect for physiologically relevant AHR ligands. We believe that there is likely to be cell- and tissue-type specificity and redundancy for endogenous AHR ligands. It should now be possible to identify CYP1-mediated AHR ligands by comparing metabolite profiles from an assortment of tissues of the wild-type mouse with those of various combinations of the Cyp1 knock-out lines that are now available.

Other Evidence of Endogenous Functions of AHR—In untreated mice, the highest AHR level in any cell type is seen in the oocyte (19), and incredibly high levels of CYP1A1 mRNA are found in the oocyte after fertilization (20). Interestingly, retinoic acid-induced differentiation in cultured cells and hepatic regeneration in the intact mouse are both associated with up-regulation of CYP1A1 in the absence of an exogenous inducer (21). Physical fluid shear stress in the animal (9, 18) and UVB radiation (290–320 nm) (22), as well as changing of growth medium in cultured cells, also up-regulate CYP1 and/or activate AHR (reviewed in Ref. 9). Needless to say, division of the oocyte to the two-cell stage, further cell divisions, cell differentiation and proliferation, mechanical trauma and fluid shear stress, and UV radiation all involve eicosanoids (supplemental Table S2).

Eicosanoid Action in the GI Tract—In studies of Arnt–/– conditional knock-out mice in which Cre recombinase is driven by a villin promoter, the result is complete ablation of ARNT in GI epithelial enterocytes; curiously, CYP1A1 mRNA and enzyme activity are markedly elevated in virtually all tissues of this mouse, other than the enterocyte (23). CYP1A1 induction is greater with indole-3-carbinol added to the diet (23). These observations fit well with the theme of AHR, CYP1, and eicosanoids. The process of food absorption and digestion involves continuous low-grade inflammation (and resolution of inflammation) in the GI tract. The phytochemical indole-3-carbinol also causes eicosanoid release. Removal of ARNT from the enterocyte blocks AHR function and therefore CYP1 expression in that cell type; we hypothesize that, as a result, eicosanoids normally synthesized or degraded by the enterocyte CYP1 enzymes are released throughout the rest of the animal and that these eicosanoids are AHR ligands that then cause CYP1A1 up-regulation in virtually every cell type except ARNT-deficient enterocytes.

What Happens Downstream of Eicosanoids?

Beyond the scope of this review, eicosanoid synthesis and degradation are not the end of the story. Specific receptors for prostaglandins (24–26) and for other eicosanoids (27–29) are being characterized, many of which are G-protein-coupled receptors, but the field is still in its infancy; perhaps other heretofore unknown reception systems also exist (Fig. 1C). Our understanding about the release of ω-6 and ω-3 fatty acids from phospholipids and diacylglycerol and about the synthesis and degradation of specific eicosanoids by certain ALOX and CYP enzymes may well lead to the design of new drug targets. Similarly, a better understanding of eicosanoid receptors and their targets should also result in more knowledge and possible new drug targets in treating various human disorders, including specific types of cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Naonori Uozumi for critical reading of this manuscript and our colleagues, especially Charles N. Serhan, for valuable discussions.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant P30 ES06096. This minireview will be reprinted in the 2008 Minireview Compendium, which will be available in January, 2009.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental material, Tables S1 and S2, and additional references.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: AHR, aryl hydrocarbon receptor; XTFs, xenosensor transcription factors; ALOX, arachidonate lipoxygenase; CYP, cytochrome P450; PDV, patent ductus venosus; AV, arteriovenous; GI, gastrointestinal.

References

- 1.Tsitsigiannis, D. I., and Keller, N. P. (2007) Trends Microbiol. 15 109–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Serhan, C. N. (2007) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 25 101–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang, H. (2007) Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 82 4–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nebert, D. W., and Dalton, T. P. (2006) Nat. Rev. Cancer 6 947–960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nebert, D. W., and Russell, D. W. (2002) Lancet 360 1155–1162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dragin, N., Shi, Z., Madan, R., Karp, C. L., Sartor, M. A., Chen, C., Gonzalez, F. J., and Nebert, D. W. (2008) Mol. Pharmacol. 73 1844–1856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frericks, M., Meissner, M., and Esser, C. (2007) Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 220 320–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hahn, M. E., Karchner, S. I., Evans, B. R., Franks, D. G., Merson, R. R., and Lapseritis, J. M. (2006) J. Exp. Zool. Part A Comp. Exp. Biol. 305 693–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McMillan, B. J., and Bradfield, C. A. (2007) Mol. Pharmacol. 72 487–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boverhof, D. R., Tam, E., Harney, A. S., Crawford, R. B., Kaminski, N. E., and Zacharewski, T. R. (2004) Mol. Pharmacol. 66 1662–1670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cowart, L. A., Wei, S., Hsu, M. H., Johnson, E. F., Krishna, M. U., Falck, J. R., and Capdevila, J. H. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 35105–35112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Machado, F. S., Esper, L., Dias, A., Madan, R., Gu, Y., Hildeman, D., Serhan, C. N., Karp, C. L., and Aliberti, J. (2008) J. Exp. Med. 205 1077–1086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 13.Lahvis, G. P., Pyzalski, R. W., Glover, E., Pitot, H. C., McElwee, M. K., and Bradfield, C. A. (2005) Mol. Pharmacol. 67 714–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernandez-Salguero, P., Pineau, T., Hilbert, D. M., McPhail, T., Lee, S. S., Kimura, S., Nebert, D. W., Rudikoff, S., Ward, J. M., and Gonzalez, F. J. (1995) Science 268 722–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi, L. Z., Faith, N. G., Nakayama, Y., Suresh, M., Steinberg, H., and Czuprynski, C. J. (2007) J. Immunol. 179 6952–6962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gielen, J. E., and Nebert, D. W. (1971) J. Biol. Chem. 246 5189–5198 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seidel, S. D., Winters, G. M., Rogers, W. J., Ziccardi, M. H., Li, V., Keser, B., and Denison, M. S. (2001) J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 15 187–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barouki, R., Coumoul, X., and Fernandez-Salguero, P. M. (2007) FEBS Lett. 581 3608–3615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Su, A. I., Cooke, M. P., Ching, K. A., Hakak, Y., Walker, J. R., Wiltshire, T., Orth, A. P., Vega, R. G., Sapinoso, L. M., Moqrich, A., Patapoutian, A., Hampton, G. M., Schultz, P. G., and Hogenesch, J. B. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99 4465–4470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dey, A., and Nebert, D. W. (1998) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 251 657–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kimura, S., Donovan, J. C., and Nebert, D. W. (1987) J. Exp. Pathol. 3 61–74 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fritsche, E., Schafer, C., Calles, C., Bernsmann, T., Bernshausen, T., Wurm, M., Hubenthal, U., Cline, J. E., Hajimiragha, H., Schroeder, P., Klotz, L. O., Rannug, A., Furst, P., Hanenberg, H., Abel, J., and Krutmann, J. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104 8851–8856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ito, S., Chen, C., Satoh, J., Yim, S., and Gonzalez, F. J. (2007) J. Clin. Investig. 117 1940–1950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peebles, K. A., Lee, J. M., Mao, J. T., Hazra, S., Reckamp, K. L., Krysan, K., Dohadwala, M., Heinrich, E. L., Walser, T. C., Cui, X., Baratelli, F. E., Garon, E., Sharma, S., and Dubinett, S. M. (2007) Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 7 1405–1421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hao, C. M., and Breyer, M. D. (2008) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 70 357–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salinthone, S., Yadav, V., Bourdette, D. N., and Carr, D. W. (2008) Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 8 132–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nigam, S., Zafiriou, M.-P., Deva, R., Ciccoli, R., and Roux-Van der Merwe, R. (2007) FEBS J. 274 3503–3512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Romano, M., Recchia, I., and Recchiuti, A. (2007) Scientific World Journal. 7 1393–1412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Montuschi, P. (2008) Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 8 647–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holm, K. A., Park, S. S., Gelboin, H. V., and Kupfer, D. (1989) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 269 664–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanaka, S., Imaoka, S., Kusunose, E., Kusunose, M., Maekawa, M., and Funae, Y. (1990) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1043 177–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rifkind, A. B., Lee, C., Chang, T. K., and Waxman, D. J. (1995) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 320 380–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Plastaras, J. P., Guengerich, F. P., Nebert, D. W., and Marnett, L. J. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 11784–11790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schwarz, D., Kisselev, P., Ericksen, S. S., Szklarz, G. D., Chernogolov, A., Honeck, H., Schunck, W. H., and Roots, I. (2004) Biochem. Pharmacol. 67 1445–1457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Labitzke, E. M., Diani-Moore, S., and Rifkind, A. B. (2007) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 468 70–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fer, M., Dreano, Y., Lucas, D., Corcos, L., Salaun, J. P., Berthou, F., and Amet, Y. (2008) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 471 116–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choudhary, D., Jansson, I., Stoilov, I., Sarfarazi, M., and Schenkman, J. B. (2004) Drug Metab. Dispos. 32 840–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chang, M. S., Boeglin, W. E., Guengerich, F. P., and Brash, A. R. (1996) Biochemistry 35 464–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keeney, D. S., Skinner, C., Travers, J. B., Capdevila, J. H., Nanney, L. B., King, L. E., Jr., and Waterman, M. R. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273 32071–32079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Du, L., Yermalitsky, V., Ladd, P. A., Capdevila, J. H., Mernaugh, R., and Keeney, D. S. (2005) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 435 125–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Du, L., Yermalitsky, V., Hachey, D. L., Jagadeesh, S. G., Falck, J. R., and Keeney, D. S. (2006) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 316 371–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Imaoka, S., Wedlund, P. J., Ogawa, H., Kimura, S., Gonzalez, F. J., and Kim, H. Y. (1993) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 267 1012–1016 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oliw, E. H., Stark, K., and Bylund, J. (2001) Biochem. Pharmacol. 62 407–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Michaelis, U. R., Falck, J. R., Schmidt, R., Busse, R., and Fleming, I. (2005) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 25 321–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thompson, C. M., Capdevila, J. H., and Strobel, H. W. (2000) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 294 1120–1130 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miyata, N., Taniguchi, K., Seki, T., Ishimoto, T., Sato-Watanabe, M., Yasuda, Y., Doi, M., Kametani, S., Tomishima, Y., Ueki, T., Sato, M., and Kameo, K. (2001) Br. J. Pharmacol. 133 325–329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laethem, R. M., Balazy, M., Falck, J. R., Laethem, C. L., and Koop, D. R. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268 12912–12918 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Node, K., Huo, Y., Ruan, X., Yang, B., Spiecker, M., Ley, K., Zeldin, D. C., and Liao, J. K. (1999) Science 285 1276–1279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qu, W., Bradbury, J. A., Tsao, C. C., Maronpot, R., Harry, G. J., Parker, C. E., Davis, L. S., Breyer, M. D., Waalkes, M. P., Falck, J. R., Chen, J., Rosenberg, R. L., and Zeldin, D. C. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 25467–25479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.King, L. M., Ma, J., Srettabunjong, S., Graves, J., Bradbury, J. A., Li, L., Spiecker, M., Liao, J. K., Mohrenweiser, H., and Zeldin, D. C. (2002) Mol. Pharmacol. 61 840–852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jiang, J. G., Chen, C. L., Card, J. W., Yang, S., Chen, J. X., Fu, X. N., Ning, Y. G., Xiao, X., Zeldin, D. C., and Wang, D. W. (2005) Cancer Res. 65 4707–4715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oleksiak, M. F., Wu, S., Parker, C., Qu, W., Cox, R., Zeldin, D. C., and Stegeman, J. J. (2003) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 411 223–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chuang, S. S., Helvig, C., Taimi, M., Ramshaw, H. A., Collop, A. H., Amad, M., White, J. A., Petkovich, M., Jones, G., and Korczak, B. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 6305–6314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu, Z. L., Sohl, C. D., Shimada, T., and Guengerich, F. P. (2006) Mol. Pharmacol. 69 2007–2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aoyama, T., Hardwick, J. P., Imaoka, S., Funae, Y., Gelboin, H. V., and Gonzalez, F. J. (1990) J. Lipid Res. 31 1477–1482 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aitken, A. E., Roman, L. J., Loughran, P. A., de la, G. M., and Masters, B. S. (2001) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 393 329–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Muller, D. N., Schmidt, C., Barbosa-Sicard, E., Wellner, M., Gross, V., Hercule, H., Markovic, M., Honeck, H., Luft, F. C., and Schunck, W. H. (2007) Biochem. J. 403 109–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mezentsev, A., Mastyugin, V., Seta, F., Ashkar, S., Kemp, R., Reddy, D. S., Falck, J. R., Dunn, M. W., and Laniado-Schwartzman, M. (2005) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 315 42–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Seta, F., Patil, K., Bellner, L., Mezentsev, A., Kemp, R., Dunn, M. W., and Schwartzman, M. L. (2007) Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 84 116–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kawashima, H., Kusunose, E., Thompson, C. M., and Strobel, H. W. (1997) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 347 148–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kikuta, Y., Kasyu, H., Kusunose, E., and Kusunose, M. (2000) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 383 225–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bylund, J., Hidestrand, M., Ingelman-Sundberg, M., and Oliw, E. H. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 21844–21849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bylund, J., and Oliw, E. H. (2001) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 389 123–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stark, K., Schauer, L., Sahlen, G. E., Ronquist, G., and Oliw, E. H. (2004) Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 94 177–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kalsotra, A., Turman, C. M., Kikuta, Y., and Strobel, H. W. (2004) Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 199 295–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Le Quere, V., Plee-Gautier, E., Potin, P., Madec, S., and Salaun, J. P. (2004) J. Lipid Res. 45 1446–1458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Harmon, S. D., Fang, X., Kaduce, T. L., Hu, S., Raj, G. V., Falck, J. R., and Spector, A. A. (2006) Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 75 169–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kalsotra, A., Anakk, S., Brommer, C. L., Kikuta, Y., Morgan, E. T., and Strobel, H. W. (2007) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 461 104–112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ward, N. C., Tsai, I. J., Barden, A., van Bockxmeer, F. M., Puddey, I. B., Hodgson, J. M., and Croft, K. D. (2008) Hypertension 51 1393–1398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hawkins, D. J., and Brash, A. R. (1989) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 268 447–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kulas, J., Schmidt, C., Rothe, M., Schunck, W. H., and Menzel, R. (2008) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 472 65–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vance, R. E., Hong, S., Gronert, K., Serhan, C. N., and Mekalanos, J. J. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101 2135–2139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bannenberg, G. L., Aliberti, J., Hong, S., Sher, A., and Serhan, C. (2004) J. Exp. Med. 199 515–523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.