Abstract

Microtubules are among the most successful targets of compounds potentially useful for cancer therapy. A new series of inhibitors of tubulin polymerization based on the 2-amino-3-(3,4,5-trimethoxybenzoyl)-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrothieno[b]pyridine molecular skeleton was synthesized and evaluated for antiproliferative activity, inhibition of tubulin polymerization, and cell cycle effects. The most promising compound in this series was 2-amino-3-(3,4,5-trimethoxybenzoyl)-6-methoxycarbonyl-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrothieno[b]pyridine, which inhibits cancer cell growth with IC50-values ranging from 25 to 90 nM against a panel of four cancer cell lines, and interacts strongly with tubulin by binding to the colchicine site. In this series of N6-carbamate derivatives, any further increase in the length and in the size of the alkyl chain resulted in reduced activity.

Keywords: Microtubules; Combretastatin-A4; Tubulin polymerization; 4,5,6,7-Tetrahydrothieno[b]pyridine; Colchicine

The mitotic spindle is formed by microtubules that are generated by the polymerization of tubulin, and the spindle is an attractive target for the development of compounds useful in anticancer chemotherapy.1 Besides being critical for cell division, the microtubule system of eukaryotic cells is involved in many fundamental cellular functions, including cell signaling, secretion, cell architecture in interphase, and intracellular transport.2 A large number of antimitotic drugs displaying wide structural diversity, derived from natural sources or by screening compound libraries in combination with traditional medicinal chemistry, have been identified and shown to interfere with the tubulin system.3

One of the most important naturally occurring tubulin-binding agents is combretastatin A-4 (CA-4, 1; Chart 1). CA-4, isolated from the bark of the South African tree Combretum caffrum,4 strongly inhibits the polymerization of tubulin by binding to the colchicine site.5 Because of its simple structure, a wide number of CA-4 analogues have been developed and evaluated in SAR studies.6

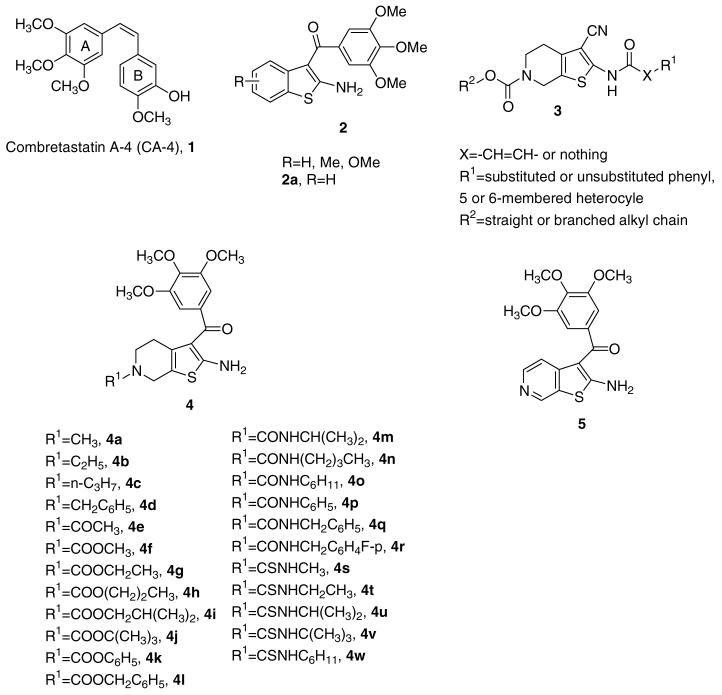

Chart 1.

Inhibitors of tubulin polymerization.

During our studies directed at the synthesis of new antitubulin agents, we previously reported the potent in vitro antitumor activity of a series of molecules with general structure 2, characterized by the presence of a 2-amino-3-(3,4,5-trimethoxybenzoyl)-benzo[b]thiophene skeleton.7 These compounds strongly inhibited tumor cell growth, as well as tubulin polymerization by binding to the colchicine site of tubulin, and caused arrest in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle. The trimethoxybenzoyl moiety is crucial for retaining potency in this and other series of molecules which occupy the colchicine site.8

Previously, investigators at Altana Pharma reported a series of 2-amido-3-cyano-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrothieno[2,3-b]pyridine analogues with general structure 3, active at micromolar concentrations (IC50 = 0.2-5 μM) as antiproliferative agents against human colon adenocarcinoma (RKOp27) cells.9

As a part of our search for novel antimitotic agents, these findings prompted us to synthesize a new series of 2-amino-3-(3,4,5-trimethoxybenzoyl)-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrothieno[b]pyridine derivatives with general structure 4, obtained by combining the 2-amino-3-(3′,4′,5′-trimethoxybenzoyl)thiophene portion of compound with general structure 2 with the N6-substituted-4,5,6,7-tetrahydropyridine nucleus of general structure 3.

To the best of our knowledge, there have been no reports that molecules characterized by the presence of the 4,5,6,7-tetrahydrothieno[b]pyridine skeleton can inhibit tubulin polymerization. In order to explore the structure-activity relationships (SARs) at the N6-position of the 2-amino-3-(3,4,5-trimethoxybenzoyl)-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrothieno[b]pyridine nucleus, we embarked upon the synthesis of different series of N6-substituted derivatives, represented by alkyl compounds 4a-d, amide 4e, carbamates 4f-l, ureas 4m-r, and thioureas 4s-w, characterized by the presence of alkyl chains of varying size. In addition, we explored the effect of bioisosteric replacement of the C-6 carbon atom of derivative 2a with a nitrogen atom, to furnish the 2-amino-3-(3′,4′,5′-trim-ethoxybenzoyl)thieno[2,3-c]pyridine derivative 5.

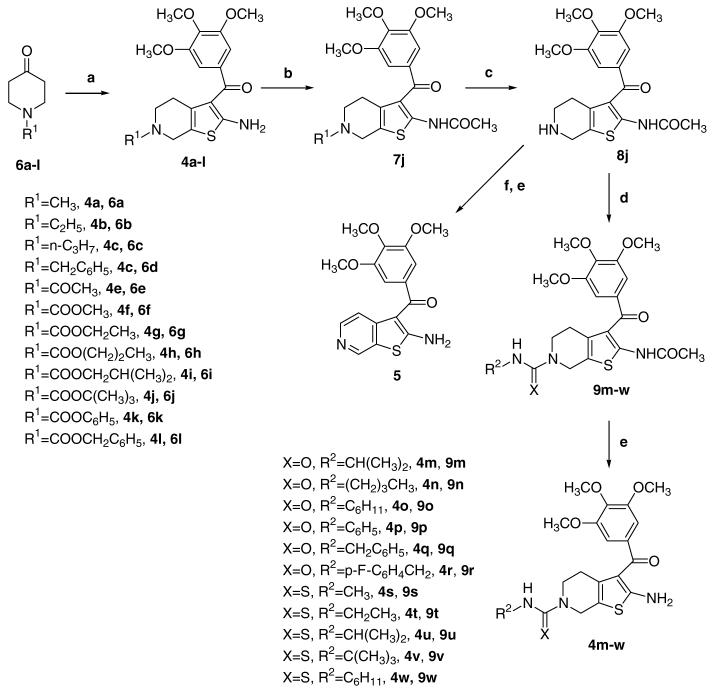

Synthesis of derivatives 4a-w and 5 was carried out by the general methodology shown in Scheme 1. The Gewald reaction10, applied to 3-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)-3-oxopropanenitrile,11 sulfur, and N-substituted 4-piperidone 6a-l12 in the presence of triethylamine and ethanol at reflux, furnished the 2-amino-3-(3′,4′,5′-trimethoxybenzoyl)-6-substituted-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrobenzo[b]-thiophenes 4a-l. 13 The N6-tert-butoxycarbonyl (Boc) derivative 4j was used as starting material for the synthesis of urea and thiourea derivatives 4m-r and 4s-w, respectively. Acetylation of the amino group of 4j, using acetyl chloride and pyridine, yielded 7j, which, followed by removal of the N6-Boc protecting group with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), afforded the derivative 8j. The subsequent aromatization, by treatment with manganese dioxide (MnO2) in refluxing toluene, furnished the corresponding N2-acetyl-thieno[2,3-c]pyridine derivative, transformed by saponification into the final product 5.

Scheme 1.

Compound 8j was further condensed with different isocyanates or isothiocyanates, in the presence of triethylamine, to afford the corresponding ureas 9m- and thioureas 9s-w, which were transformed by hydrolysis with NaOH into the final products 4m-r and 4s-w, respectively, in good yields.

Table 1 summarizes the antiproliferative activity of N6-substituted-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrothieno[b]pyridine derivatives 4a-w and the thieno[2,3-c]pyridine 5 against the growth of murine leukemia (L1210), murine mammary carcinoma (FM3A), and human T-lymphoblastoid (Molt/4 and CEM) cells, using CA-4 (1) and the benzo[b]thiophene derivative 2a as reference compounds. The results indicated that N6-methyl and ethyl carbamates 4f and 4g,14 respectively, showed the most potent antiproliferative activities, while N6-branched alkyl or aryl carbamates as well as alkyl, acetyl, urea, and thiourea functionalities decreased activity drastically.

Table 1.

In vitro inhibitory effects of compounds 2a, 4a-w, 5, and CA-4 (1) against the proliferation of murine leukemia (L1210), murine mammary carcinoma (FM3A), and human T-lymphocyte (Molt/4 and CEM) cells

| Compound | IC50a (nM) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1210 | FM3A | Molt4/C8 | CEM | |

| 4a | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 |

| 4b | 2100 ± 100 | 1900 ± 0.0 | 1800 ± 0.0 | 1700 ± 0.0 |

| 4c | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 |

| 4d | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 |

| 4e | 3900 ± 290 | 1200 ± 100 | 1100 ± 60 | 1400 ± 20 |

| 4f | 25 ± 1 | 46 ± 1.3 | 45 ± 3.1 | 90 ± 1.7 |

| 4g | 95 ± 3.3 | 57 ± 3.8 | 290 ± 25 | 440 ± 30 |

| 4h | 1100 ± 80 | 1400 ± 100 | 470 ± 0.00 | 1200 ± 30 |

| 4i | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 |

| 4j | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 |

| 4k | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 |

| 4l | >10,000 | >10,000 | 7500 ± 140 | 8300 ± 500 |

| 4m | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 |

| 4n | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 |

| 4o | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 |

| 4p | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 |

| 4q | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 |

| 4r | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 |

| 4s | 4900 ± 470 | 2800 ± 110 | 1600 ± 60 | 1800 ± 70 |

| 4t | 6800 ± 430 | 6900 ± 290 | 4800 ± 370 | 6700 ± 550 |

| 4u | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 |

| 4v | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 |

| 4w | 1100 ± 60 | 1400 ± 50 | 750 ± 58 | 730 ± 71 |

| 5 | 370 ± 160 | 400 ± 170 | 340 ± 40 | 1000 ± 900 |

| 2a | 90 ± 3 | 100 ± 0 | 73 ± 9 | 74 ± 15 |

| CA-4 (1) | 2.8 ± 1.1 | 42 ± 6 | 1.6 ± 1.4 | 1.9 ± 1.6 |

IC50 = compound concentration required to inhibit tumor cell proliferation by 50%. Data are expressed as means ± SE from the dose-response curves of at least three independent experiments.

Of all the tested compounds, the N6-methyl carbamate derivative 4f possessed the highest potency, inhibiting the growth of L1210, FM3A, Molt/4, and CEM cancer cell lines with IC50s of 25, 46, 45, and 90 nM, respectively.

The results indicated that a non-basic nitrogen atom at the N6-position of 4,5,6,7-tetrahydrothieno[b]pyridine nucleus was important for inhibition of cell growth. In fact, in the series of N6-alkyl derivatives 4a-d, only the ethyl derivative 4b showed moderate potency (IC50 = 1.7-2.1 μM), whereas for the methyl, propyl, and benzyl analogues (compounds 4a, 4c, and 4d, respectively), the IC50 was greater than 10 μM in all four cell lines. The N6-acetyl derivative 4e also showed moderate antiproliferative activity, with IC50-values of 1.1-3.9 μM:

In the series of carbamates 4f-l, a small substituent size was important for good activity. Only the methyl and ethyl derivatives 4f and 4g, respectively, showed potent antiproliferative activity, with 4f more active than 4g. Specifically, 4f and 4g had similar activity against FM3A cells, but 4f was 4-, 5-, and 6-fold more potent then 4g against L1210, CEM and Molt4 cells, respectively. A further increase in the length of the straight alkyl chain, to furnish the propyl derivative 4h, caused 10-, 25-, 1.5-, and 3-fold reductions in activity with the L1210, FM3A, Molt-4, and CEM cells, respectively. With still bulkier carbamate moieties, there was essentially total loss of activity. All urea derivatives 4m-r were also inactive (IC50 >10 μM).

It is noteworthy that for the active compounds 4f and 4g, the replacement of the carbamate group with a thiourea, to furnish the corresponding derivatives 4s and 4t, produced a dramatic drop in potency (IC50 = 1.6-4.9 μM and 4.8-6.9 μM for 4s and 4t, respectively, versus IC50 = 25-90 nM and 57-440 nM for 4f and 4g, respectively).

In the series of thiourea derivatives 4s-w, the cyclohexyl thiocarbamoyl derivative 4w resulted in the most active compound, with IC50s of 0.73-1.1 μM. Comparing urea and thiourea derivatives with the same substitution at the N6-position (4m vs 4u and 4o vs 4w), while the isopropyl derivatives 4m and 4u were both inactive, the cyclohexyl thiourea derivative 4w was more active than the urea derivative 4o.

Finally, comparing the benzo[b]thiophene 2a with the thieno[2,3-c]pyridine 5, replacement of the benzene with the bioisosteric pyridine ring led to a significant loss of activity. Compound 5 was 4- to 6-fold less active than 2a against L1210, FM3A, and Molt-4 cells. Reduction in potency was even more pronounced with the CEM cells, with 5 being 13-fold less potent than 2a. Moreover, the corresponding tetrahydrothieno[b]pyridine analogue of 5 resulted inactive (IC50 >10 μM), indicating that the aromaticity of the pyridine ring fused with the thiophene was critical for activity.

To investigate whether the antiproliferative activities of these compounds were related to an interaction with the microtubule system, compounds 4f-g and 5 and reference derivatives 2a and CA-4 were evaluated for inhibitory effects on tubulin polymerization, and on the binding, of [3H]colchicine to tubulin (Table 2).15,16 For compounds 2a and 5, there was a positive correlation between inhibition of both tubulin polymerization and colchicine binding, and antiproliferative activity. However, relative to 2a, both 4f and 4g were disproportionately more active as assembly inhibitors, and these compounds also had greater activity as inhibitors of colchicine binding. The IC50s of 0.6 μM obtained with 4f and 4g are among the lowest ever observed in this assembly assay, and half that obtained in simultaneous experiments for CA-4 (IC50, 1.2 μM). Nonetheless, CA-4 had greater antiproliferative activity and a greater inhibitory effect on the four cell lines than both 4f and 4g. In addition, we should note that the similar effects of 4f and 4g in the tubulin-based assays differed from the greater activity observed with 4f in the antiproliferative studies. This could derive from preferential cellular uptake of 4f relative to 4g. Alternatively, it is possible that cellular tubulin differs from the neural tubulin used in the biochemical assays in its affinities for the two compounds.

Table 2.

Inhibition of tubulin polymerization and colchicine binding by compounds 2a, 4f-g, 5, and CA-4

| Compound | Tubulin assemblya IC50 ± SD (μM) |

Colchicine bindingb ±SD (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 μM inhibitor | 5 μM inhibitor | ||

| n.d., not done. | |||

| 2a | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 25 ± 2 | 71 ± 1 |

| 4f | 0.6 ± 0.02 | 71 ± 0.6 | 84 ± 3 |

| 4g | 0.6 ± 0.03 | 67 ± 2 | 82 ± 2 |

| 5 | 5.4 ± 0.4 | n.d. | 27 ± 0.1 |

| CA-4 (1) | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 90 ± 1 | 99 ± 0.7 |

Inhibition of tubulin polymerization. Tubulin was at 10 μM.

Inhibition of [3H]colchicine binding. Tubulin and colchicine were at 1 and 5 μM, respectively, and the tested compound was at the indicated concentration.

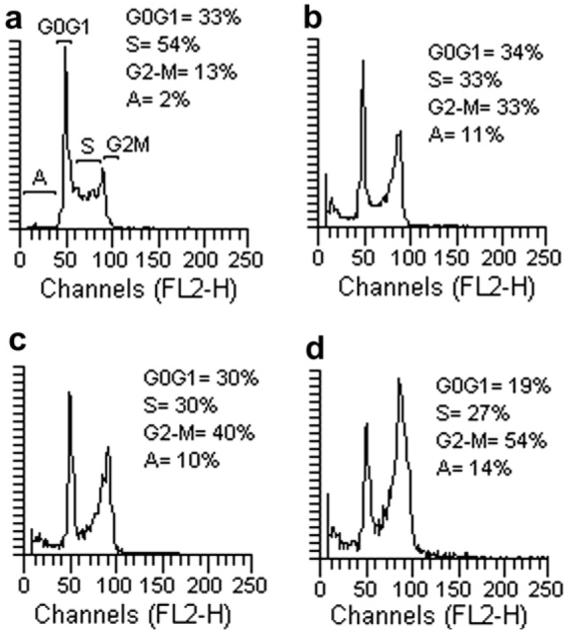

Because molecules exhibiting effects on tubulin assembly should cause alteration of cell cycle parameters, with preferential G2-M blockade, flow cytometry analysis was performed to determine the effect of the most active compounds on K562 (human chronic myelogenous leukemia) cells.17 Cells were cultured for 24 h in the presence of each compound at the IC50 determined for 24 h of growth (4f = 70 nM, 4g = 80 nM, 5 = 500 nM). Figure 1 shows that these molecules caused a marked increase in the percentage of cells blocked in the G2-M phase of the cell cycle, with a simultaneous decrease of cells in S and G0-G1. These data confirm that this class of derivatives acts selectively on the G2-M phase of the cell cycle, as expected for inhibitors of tubulin assembly.

Figure 1.

Effects of compounds 4f (panel b), 4g (panel c), and 5 (panel d) on DNA content/cell following treatment of K562 cells for 24 h. The cells were cultured without compound (panel a) or with compound used at the concentration leading to 50% cell growth inhibition after 24 h of treatment. Cell cycle distribution was analyzed by the standard propidium iodide procedure. Sub-G0-G1 (apoptotic peak, A), G0-G1, S, and G2-M cells are indicated in the panel (a).

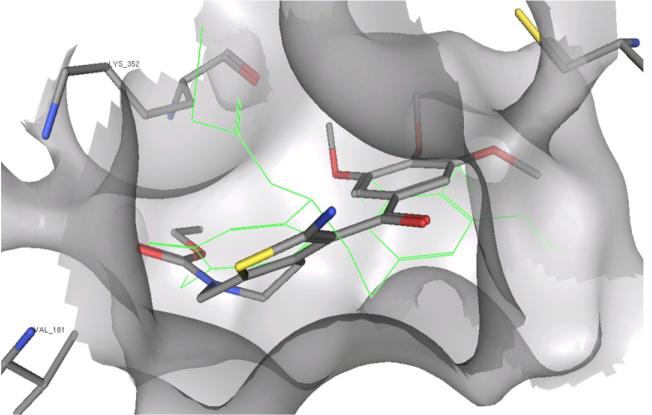

The proposed mechanism of action is also supported by docking studies of compound 4g in the colchicine site of tubulin18 (methodology reported previously).7 Figure 2 shows how the trimethoxyphenyl moiety of 4g is situated in the same pocket on b-tubulin as the structurally analogous ring A of the co-crystallized DAMA-colchicine. In this model, the carbonyl group of the carbamate of 4g overlaps the carbonyl group of ring C of DAMA-colchicine. Furthermore, the alkyl substituent of the carbamate lies in a small hydrophobic pocket deep in the binding cavity, which can only accommodate a small group like methyl or ethyl. This model thus is consistent with the SARs observed in the antiproliferative studies, and is in accord with previously reported results.19

Figure 2.

Docking pose of compound 4g in the colchicine site. DAMA-colchicine in green.

In conclusion, the synthesis and the SAR of a series of 2-amino-3-(3,4,5-trimethoxybenzoyl)-6-substituted-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrothieno[b]pyridines, which incorporated partial structures of both 2-amino-3-(3,4,5-trimethoxybenzoyl)-benzo[b]thiophene and 2-acetamido-3-cyano-6-alkoxycarbonyl-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrothieno [2,3-b]pyridine with general structures 2 and 3, respectively, are described. In particular, compounds 4f and 4g are the best amalgamation of structures 2 and 3. Derivatives 4f and 4g were highly active as inhibitors of tubulin assembly, with IC50s half that of CA-4. They also were strong inhibitors of the binding of colchicine to tubulin, although somewhat less active than CA-4. Consistent with their antitubulin activity, both 4f and 4g caused cells to arrest in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle.

Molecular docking studies with 4g into the colchicine site18 provided a rationale for our observations. The trimethoxybenzene ring and the carbamate carbonyl of 4g could bind in the same manner as the trimethoxybenzene ring A and the ring C carbonyl, respectively, of DAMA-colchicine in the crystal structure.18 An adjacent pocket in b-tubulin could readily accommodate only a methyl or ethyl group, consistent with the SAR observations.

Finally, we should note that the synthesis of 4f was efficient and produced the compound in high yield. Thus, 4f represents the lead compound of an interesting new class of antitubulin agents with potential to be developed clinically for anticancer chemotherapy.

Footnotes

Supplementary data Detailed synthesis and spectroscopic data for compounds 4a-w, 5, 6h-i, 7-8j, and 9m-w can be found in the online version. Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.08.006.

Supplementary Material

References and notes

- 1.(a) Jordan MA, Wilson L. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2004;4:253. doi: 10.1038/nrc1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Pasquier E, Andrè N, Braguer D. Curr. Cancer Drug Tar. 2007;7:566. doi: 10.2174/156800907781662266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Sorger PK, Dobles M, Tournebize R, Hyman AA. Curr. Opin. Cell. Biol. 1997;9:807. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80081-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Walczak CE. Curr. Opin. Cell. Biol. 2000;12:52. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)00056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Honore S, Pasquier E, Braguer D. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2005;62:3039. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5330-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Pellegrini F, Budman DR. Cancer Invest. 2005;23:264. doi: 10.1081/cnv-200055970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Attard G, Greystoke A, Kaye S, De Bono J. Pathol. Biol. 2006;54:72. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pettit GR, Singh SB, Hamel E, Lin CM, Alberts DS, Garcia-Kendall D. Experientia. 1989;45:209. doi: 10.1007/BF01954881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin CM, Ho HH, Pettit GR, Hamel E. Biochemistry. 1989;28:6984. doi: 10.1021/bi00443a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Tron GC, Pirali T, Sorba G, Pagliai F, Busacca S, Genazzani AA. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:3033. doi: 10.1021/jm0512903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mahindroo N, Liou JP, Chang JY, Hsieh HP. Exp. Opin. Ther. Pat. 2006;16:647. [Google Scholar]; (c) Nam NH. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003;10:1697. doi: 10.2174/0929867033457151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Hsieh HP, Liou JP, Mahindroo N. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2005;11:1655. doi: 10.2174/1381612053764751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Romagnoli R, Baraldi PG, Carrion MD, Lopez Cara C, Preti D, Fruttarolo F, Pavani MG, Tabrizi MA, Tolomeo M, Grimaudo S, Di Antonietta C, Balzarini J, Hadfield JA, Brancale A, Hamel E. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:2273. doi: 10.1021/jm070050f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cushman M, Nagarathnam D, Gopal D, He H-M, Lin CM, Hamel E. J. Med. Chem. 1992;35:2293. doi: 10.1021/jm00090a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Bartels B, Gimmnich P, Pekari K, Baer T, Schmidt M, Beckers T. WO 2005118592, 2005. Chem. Abstr. 2005:2568718. [Google Scholar]; (b) Pekari K, Baer T, Bertels B, Schmidt M, Beckers T. WO 2005118071, 2005. Chem. Abstr. 2005:2567648. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tinney FJ, Sanchez JP, Nogas JA. J. Med. Chem. 1974;17:624. doi: 10.1021/jm00252a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seneci P, Nicola M, Inglesi M, Vanotti E, Resnati G. Synth. Commun. 1999;2:311. [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Xu G, Kannan A, Hartman TL, Wargo H, Watson K, Turpin JA, Buckheit RW, Johnson AA, Pommier Y, Cushman M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2002;10:2807. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(02)00095-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mauleon D, Antunez S, Rosell G. Farmaco. 1989;44:1109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Phenyl isocyanate, benzyl isocyanate, 4-fluorobenzyl isocyanate, isopropyl isocynate, butyl isocyanate, cyclohexyl isocyanate, methyl isothiocyanate, ethyl isothiocyanate, isopropyl isothiocyanate, cyclohexyl isothiocyanate, tert-butyl isothiocyanate, 1-methyl-4-piperidone (6a), 1-ethyl-4-piperidone (6b), 1-n-propyl-4-piperidone (6c), 1-benzyl-4-piperidone (6d), 1-acetyl-4-piperidone (6e), 1-ethoxycarbonyl-4-piperidone (6g), n-propyl 4-oxopiperidine-1-carboxylate (6h), isobutyl 4-oxopiperidine-1-carboxylate (6i), 1-tert-butyloxycarbonyl-4-piperidone (6j), and 1-benzyloxycarbonyl-4-piperidone (6l) are commercially available and were used as received. For the synthesis of 4-oxo-piperidine-1-carboxylic acid methyl ester (6f) see:; For the synthesis of 4-oxo-piperidine-1-carboxylic acid phenyl ester (6k) see:

- 13.General procedure for the synthesis of compounds (4a-l). To a suspension of 3-oxo-3-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)-propionitrile (2.55 g., 10 mmol), TEA (1.54 mL, 11 mmol), and sulfur (352 mg, 11 mmol) in EtOH (50 mL) was added the appropriate 1-substituted-4-piperidone 6a-l (10 mmol). After stirring for 2 h at 70 °C, the solvent was evaporated and the residue diluted with DCM (15 mL). After washing with water (2 × 5 mL) and brine (5 mL), the organic layer was dried and evaporated. The crude product was purified by column chromatography and crystallized from petroleum ether.

- 14.Characterization of compound 4f. Yellow solid, mp 85-87 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ: 2.07 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H), 3.44 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H), 3.74 (s, 3H), 3.86 (s, 6H), 3.90 (s, 3H), 3.95 (bs, 2H), 4.43 (s, 2H), 6.72 (s, 2H). Characterization of compound 4g. Yellow solid, mp 65-67 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ: 1.26 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 2.14 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 2H), 3.44 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 2H), 3.86 (s, 6H), 3.89 (s, 3H), 3.90 (bs, 2H), 4.18 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 4.42 (s, 2H), 6.72 (s, 2H)

- 15.Hamel E. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2003;38:1. doi: 10.1385/CBB:38:1:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verdier-Pinard P, Lai J-Y, Yoo H-D, Yu J, Marquez B, Nagle DG, Nambu M, White JD, Falck JR, Gerwick WH, Day BW, Hamel E. Mol. Pharmacol. 1998;53:62. doi: 10.1124/mol.53.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flow cytometric analysis of cell cycle distribution. The effects of the most active compounds of the series on cell cycle distribution were studied on K562 cells by flow cytometric analysis after staining with propidium iodide. Cells were exposed 24 h to each compound used at a concentration corresponding to the IC50 evaluated after a 24 h incubation. After treatment, the cells were washed once in ice-cold PBS and resuspended at 1 × 106 per mL in a hypotonic fluorochrome solution containing propidium iodide (Sigma) at 50 lg/mL in 0.1% sodium citrate plus 0.03% (v/v) nonidet P-40 (Sigma). After a 30-min incubation, the fluorescence of each sample was analyzed as single-parameter frequency histograms by using a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). The distribution of cells in the cell cycle was analyzed with the ModFit LT3 program (Verity Software House, Inc.)

- 18.Ravelli RBG, Gigant B, Curmi PA, Jourdain I, Lachkar S, Sobel A, Knossow M. Nature. 2004;428:198. doi: 10.1038/nature02393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Martino G, Edler MC, La Regina G, Coluccia A, Barbera MC, Barrow D, Nicholson RI, Chiosis G, Brancale A, Hamel E, Artico M, Silvestri R. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:947. doi: 10.1021/jm050809s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.