Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) is an inherited disease affecting the structure and function of the cilia lining the respiratory tract. Because functioning cilia are paramount in mucociliary clearance mechanisms, PCD results in recurrent ear, nose and lung infections, as well as neonatal respiratory distress. Kartagener’s syndrome, a triad of situs inversus totalis, recurrent sinusitis and bronchiectasis was first described in 1933, and is now recognized as only one of the classical phenotypes of PCD (Figure 1). Infertility occurs in the majority of males with PCD. Hydrocephalus, complex heart disease, polysplenia and biliary atresia are uncommon associations.

Figure 1).

High resolution computed tomography scan of the chest of an eight-year-old boy with Kartagener’s syndrome (primary ciliary dyskinesia with situs inversus totalis) showing extensive bronchiectasis at a young age

PCD is a rare disease with an estimated incidence of approximately 1:15,000; thus, it often does not get attention in a medical school curriculum and is not the focus of much research. As a result, it is often underdiagnosed and undertreated. There are many myths about the presentation and treatment of PCD that are only becoming evident with newer multicentre collaborative research efforts that have allowed larger numbers of patients to be studied together. The present brief commentary will touch on some of the myths and realities of PCD that have recently become evident.

Myth #1: PCD is a benign disease associated with a normal lifespan

Most medical textbooks still propagate the myth that PCD is a mild disease associated with a normal lifespan. We have now learned through large population-based studies and registries that there is a wide spectrum of severity of lung disease in PCD, from relatively normal lung function associated with a normal lifespan to progressive widespread bronchiectasis with need for lung transplantation in early adulthood (1). Although the very limited longitudinal data (2) available suggest that pulmonary function may be stable over many years when appropriate therapy is instituted, the largest cross-sectional study (3) to date, which evaluated over 100 North American patients with PCD, suggests that there is a definite decline in lung function with age, with many adult patients having lung function within the transplant range.

Ear disease is another problem that often leads to multiple medical and surgical interventions in patients with PCD. More than 90% of patients experience either recurrent otitis media or chronic serous otitis during their early childhood years (4). This often leads to hearing loss and speech delay, which can be a large source of anxiety to the family, even though the hearing loss may only be temporary (5).

Contrary to the widespread belief that PCD is a benign disease, a population-based study (6) in the United Kingdom showed that PCD patients of all ages suffer a significant burden of disease symptoms and decreased quality of life.

Myth #2: PCD is a Caucasian disease

Case series of patients recruited in tertiary care centres typically report predominantly Caucasian patients, which has led to the belief that gene mutations associated with PCD occur predominantly in white populations (3). However, the registry data (7) from the PCD clinic (The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ontario) suggest a much more heterogeneous picture, with 40% of the PCD population being of non-Caucasian origin (mainly Asian). The fact that most patients recruited for studies at tertiary care centres are Caucasian likely highlights the underdiagnosis of this disease, particularly in visible minority populations.

Myth #3: PCD does not ‘wheeze’

Many children with PCD are initially misdiagnosed with ‘atypical asthma’ (4). This is not surprising because PCD is a chronic obstructive airway disease associated with neutrophilic airway inflammation (8). Similar to cystic fibrosis (CF), bronchodilator reversibility, at least on a partial or intermittent basis, is common (9).

Myth #4: PCD is not treatable

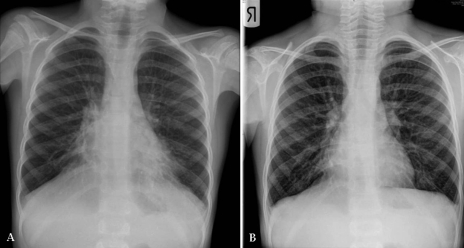

It is interesting to compare PCD with CF because both are chronic airway diseases associated with impaired mucociliary clearance and chronic infection leading to bronchiectasis. To date, there is no cure available for CF. However, aggressive medical management including routine monitoring of lung function and sputum bacteriology, the practice of daily airway clearance techniques, and aggressive directed antibiotic therapy for disease exacerbations and chronic infection has increased the survival in CF from early childhood to mid-30s and beyond over the past 50 years (10). Controlled studies (11) of neonatal screening in CF also show that earlier diagnosis is associated with improved health outcomes. One would expect to have the same kind of benefits with earlier diagnosis and aggressive medical management of PCD (Figure 2). There are some limited observational data (2,6) that suggest that this is indeed the case.

Figure 2).

Chest x-ray of a seven-year-old boy with primary ciliary dyskinesia before (A) and after (B) hospitalization for aggressive medical management of a respiratory exacerbation. There had been a slowly increasing productive cough with a decline in lung function before hospitalization. Therapy in hospital consisted of chest physiotherapy and intravenous antibiotics. Lung function (forced expiratory volume in 1 s) improved from 45% predicted to 85% predicted after 10 days of therapy

Reality #1: Diagnostic testing for PCD is difficult to access

A survey (6) of PCD patients belonging to the United Kingdom PCD Family Support Group reported that the average age of diagnosis was 9.1 years in patients with situs inversus and 13.8 years in patients with situs solitus. Considering that PCD is an inherited disease that usually presents with symptoms in infancy, this is a disappointing fact. One of the common frustrations of many patients with PCD is that they often have consulted with multiple physicians before the diagnosis is finally made in a tertiary care centre with expertise in the diagnosis of PCD. The gold standard diagnostic test, electron microscopy showing an ultrastructural defect in the cilia, requires a labour-intensive specific protocol that is only available in specialized centres with an experienced pathologist and an appropriate electron microscope. Shipping of specimens from smaller centres is fraught with difficulties. In addition, ciliary movement and normal ultrastructure does not always exclude the diagnosis of PCD, further complicating the diagnosis.

Clinical genetic testing for DNAH5 and DNAI1 mutations has recently become available as another relatively simple diagnostic test for PCD. Because these two genes code for proteins in the outer dynein arm, mutations in these genes identify less than 25% of the PCD population and only those with outer dynein arm defects. The test is currently only available through American laboratories, necessitating laborious paperwork and long wait times to receive government approval for funding of these tests.

Reality #2: Specialty care for PCD is difficult to access

Patients with CF all across Canada have experienced an excellent level of care in a well-organized network of specialty clinics largely due to the efforts and financial support of the Canadian Cystic Fibrosis Foundation <www.ccff.ca>. A PCD Foundation has only recently been established in the United States and, thus, it is not able to financially support clinics just yet <www.pcdfoundation.org>. The myth that PCD is a benign disease probably also creates a certain amount of apathy toward PCD, and hinders the same kind of aggressive treatment that we have been providing for CF patients for many years.

Expected advances in the near future

Although the current realities of PCD care are somewhat glib, rapid progress is being made through multisite research collaborations in North America and Europe and through the establishment of patient-driven PCD foundations. Earlier and easier diagnosis is becoming a possibility with the identification of nasal nitric oxide as a screening test for older children and adults (3) (Figure 3). Situs ambiguous has been demonstrated to be an infrequent and probably under-recognized phenotype associated with PCD (12). New genetic mutations associated with different PCD phenotypes are being identified, and they offer the potential for an easy blood test and prenatal diagnosis for many more children in the near future. Multisite collaborations offer the potential for clinical trials in this rare disease. Canadian patients with PCD can now participate in research through the National Institutes of Health-sponsored ‘Genetic Diseases of Mucociliary Clearance Consortium’ site at The Hospital for Sick Children <www.rarediseasesnetwork.epi.usf.edu>. With the increasing research and public attention that is being focused on PCD, advances in disease management will almost certainly occur and there will be new hope for this orphan disease.

Figure 3).

Nasal nitric oxide measurement. This noninvasive screening test is performed by placing a soft olive in one nostril and aspirating air from the nostril into a chemiluminescence analyzer which measures the concentration of nitric oxide in parts per billion. The child blows against a resistor to close the velum and prevent contamination with lower airway gases. Photo credit: Sharon D Dell

REFERENCES

- 1.Date H, Yamnumita M, Nagahiro I, Aoe M, Andou A, Shimizu N. Living-donor lobar lung transplantation for primary ciliary dyskinesia. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:2008–9. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)02276-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellerman A, Bisgaard H. Longitudinal study of lung function in a cohort of primary ciliary dyskinesia. Eur Respir J. 1997;10:2376–9. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10102376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noone PG, Leigh MW, Sannuti A, et al. Primary ciliary dyskinesia: Diagnostic and phenotypic features. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:459–67. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200303-365OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coren ME, Meeks M, Morrison I, Buchdahl RM, Bush A. Primary ciliary dyskinesia: Age at diagnosis and symptom history. Acta Paediatr. 2002;91:667–9. doi: 10.1080/080352502760069089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Majithia A, Fong J, Hariri M, Harcourt J. Hearing outcomes in children with primary ciliary dyskinesia – a longitudinal study. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;69:1061–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McManus I, Mitchison H, Chung E, Stubbings G, Martin N. Primary ciliary dyskinesia (Siewert’s/Kartagener’s syndrome): Respiratory symptoms and psycho-social impact. BMC Pulm Med. 2003;3:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-3-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsieh T, Luu K, Bikangaga P, Dell SD. Primary ciliary dyskinesia is not limited to the Caucasian population. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:A160. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nadwa Zihlif EPCLL-AVDPAB Correlation between cough frequency and airway inflammation in children with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2005;39:551–7. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hellinckx J, Demedts M, De Boeck K. Primary ciliary dyskinesia: Evolution of pulmonary function. Eur J Pediatr. 1998;157:422–6. doi: 10.1007/s004310050843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis PB. Cystic fibrosis since 1938. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:475–82. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200505-840OE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farrell PM, Lai HJ, Li Z, et al. Evidence on improved outcomes with early diagnosis of cystic fibrosis through neonatal screening: Enough is enough! J Pediatr. 2005;147:S30–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kennedy MP, Omran H, Leigh MW, et al. Congenital heart disease and other heterotaxic defects in a large cohort of patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Circulation. 2007;115:2814–21. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.649038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]