Children with chronic cough are frequently seen in the offices of primary care physicians and are occasionally referred for specialist opinion. The diagnostic process used in such cases usually involves a combination of history taking, physical examinations and selected investigations. Pattern recognition is often used by experienced physicians when faced with a patient whose presentation conforms to a previously learned pattern of disease. Pattern recognition may be visual, auditory or simply a cluster of signs and symptoms that suggest a particular disorder. Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) is one of those disorders.

PCD is an inherited disorder of specific ultrastructural defects of cilia that affects ciliary motion and impairs mucus clearance (1). Previously referred to as Kartagener’s syndrome in 1935 and immotile cilia syndrome in 1976, the name change in 1981 reflected the fact that cilia were not necessarily immotile, although their movement may not be rhythmic; only 50% of cases are associated with situs inversus totalis.

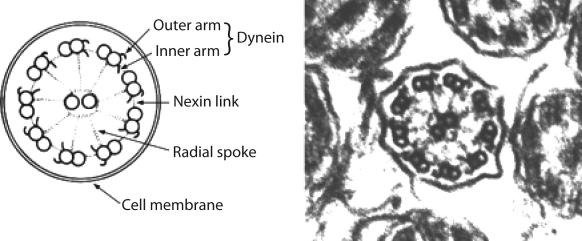

The large airways, as well as nares, paranasal sinuses and the middle ear, are lined by a ciliated epithelium that is important for mucociliary clearance. Cells contain approximately 200 cilia, each containing longitudinal microtubules consisting of nine pairs or doublets arranged in an outer circle around a central pair. Included in the structure are outer and inner dynein arms, radial spokes and nexin links involving as many as 250 proteins in one cilium (Figure 1). PCD has been reported in all ethnic groups; in most patients, inheritance follows an autosomal recessive pattern, although there are reported exceptions. Dynein arm abnormalities are the most common defects seen, but other defects involve radial spokes, nexin links and microtubular transpositions (the central pair is missing and replaced by one of the outer microtubular pairs).

Figure 1).

Schematic diagram of the basic structure of cilia. Reproduced with permission from reference 2

Normal cilia play their part in the host’s defense mechanisms and beat rhythmically at 5 beats/s to 20 beats/s aiding mucus clearance from the nose, middle ear, paranasal sinuses and airways.

Mucus is carried down the back of the nose or up the tracheobronchial tree where it is swallowed. The clinical presentation in PCD occurs as a result of the absent or abnormal movement of cilia and subsequent retention of mucus, which becomes infected. The incidence of PCD is thought to be one in 15,000 to 20,000 births, but this may be an underestimate. Although not a common condition, the consequences of overlooking the diagnosis leads to significant morbidity including chronic sinusitis, hearing loss and bronchiectasis. Approximately 50% of affected patients have situs inversus totalis, a complete mirror image reversal of the chest and abdominal organs with the liver on the left, and the heart, stomach and spleen on the right; the lungs are reversed (three lobes on the left side). In these cases, the diagnosis of PCD should be suspected earlier but is often overlooked. A minority of patients (6%) have heterotaxy or situs ambiguous, which refers to patients who do not fall into either the situs solitus or the situs inversus totalis categories. Heterotaxy has a high degree of association with intracardiac defects. The clinician should be aware of the possibility that a chest radiograph of situs inversus totalis is projected in reverse, obscuring the diagnosis. The clinical presentation includes signs and symptoms arising to various extents from the nose, ears, sinuses and lungs. Because the basic abnormality is lack of mucus clearance, the clues to the diagnosis are chronic rhinorrhea, chronic middle-ear effusion and chronic wet cough. The diagnosis of PCD should be suspected in any child with a chronic runny nose starting in the newborn period or early infancy because the majority of patients have onset of symptoms in the neonatal period. Continuous rhinorrhea from the first day of life, particularly if associated with respiratory distress or neonatal pneumonia with no obvious predisposing cause, makes the diagnosis more likely. A parent who says ‘his nose was running when I brought him home from the hospital’ or ‘I had to use saline nose drops and a bulb suction to keep her nose clear so I could feed her’ should not be ignored. The nasal discharge is usually neither profuse nor discoloured (unless the child has an associated respiratory tract infection), but the nose is chronically wet. The chronicity of the nasal symptoms becomes more apparent as the child gets older. It gradually becomes obvious that this is neither the pattern of allergic rhinitis nor is it that of intermittent acute rhinorrhea seen in association with viral upper respiratory tract infections. As one parent said, ‘she always takes tissues to school with her’. Chronic middle-ear effusions may also be seen, but can easily be confused with acute otitis media with effusion. Tympanostomy tubes are often inserted for this reason; chronic otorrhea may occur. Although some drainage is normal following tube placement in normal children, chronic drainage is not common. Discoloured, smelly and occasionally offensive discharge from the ears in a child with perforated tympanic membranes or after placement of tympanostomy tubes is a clue to the diagnosis of PCD. Tympanostomy tubes that are frequently extruded may also be an important sign. Because children with PCD often present first to ear, nose and throat surgeons, they should be aware of the possibility of this diagnosis.

Some time after infancy, usually during the toddler years, the parents become aware of their child’s chronic wet cough. The cough has a rattly sound to it, and while older children can expectorate, younger ones swallow the mucus. The cough is present even when the child has no associated respiratory infection. Parents may be so used to it that they come to recognize it as normal in their child. The cough often increases in frequency with associated respiratory tract infections, and if sputum can be produced, it is usually discoloured. Auscultation of the chest may reveal wheezes or crackles but frequently there are no adventitious sounds. Sinusitis and allergies are often suspected because of the rhinorrhea, although not usually proved. An inquiry into the family history is sometimes beneficial, particularly when it uncovers dextrocardia, lifelong nasal symptoms, bronchiectasis or male infertility.

When considering the diagnosis of PCD, investigations should include a chest radiograph. Depending on the age of the child and the chronicity of symptoms, a chest x-ray may range from normal to demonstrating bronchiectasis. Retained secretions, hyperinflation and atelectasis may be seen. Because the anatomical right middle lobe (left middle lobe in patients with situs inversus totalis) is the longest, narrowest and most horizontal of the lobar bronchi, it is the most prone to become chronically obstructed with inspissated mucus and most likely to become chronically atelectatic or bronchiectatic in PCD. Other causes of ‘right middle lobe syndrome’ include asthma, cystic fibrosis (CF) and humoral immunodeficiency. Pulmonary function tests, in patients older than six years of age and in those who are able to cooperate, may range from normal to showing evidence of airways obstruction. If the child can expectorate, sputum should be sent for culture. Hemophilus influenzae, Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae are the common bacteria. Older patients may become colonized with pseudomonas. Sweat testing and serum immunoglobulins are recommended for completeness because CF and humoral immunodeficiency can also present with chronic sinusitis and recurrent bronchopulmonary infections. Useful clues to these diagnoses include recognizing that while otitis media is often frequent and severe in both PCD and immunodeficiency, it is uncommon in CF; chronic diarrhea and failure to thrive are common in CF and immunodeficiency, but not in PCD. Constant nasal discharge tends to be more problematic in PCD patients than in patients with CF or immunodeficiency. Audiograms should be performed because of the risk of hearing loss with chronic middle-ear effusions. Chest and sinus computed tomographies are not routinely required in all cases, but only if clinically indicated. The saccharin test, a measure of nasal mucociliary clearance, is not suitable for small children who are required to sit still for 1 h. It can be used as a screening test in older children, but is rarely performed because its sensitivity and specificity are fairly low. Nasal nitric oxide levels are low in patients with PCD; in referral centres, they are used as a screening test. Confirmation of the diagnosis requires both evidence of ciliary immotility (or dysmotility) and specific ultrastructural defects. Structural defects are usually determined by electron microscopic examination of cilia obtained from a nasal mucosal biopsy, although bronchial mucosal biopsies obtained by bronchoscopy can also be used. Because ciliary structure can be altered by respiratory infections and through the preparation of the material for electron microscopy, biopsies should be examined by a pathologist who has extensive experience examining normal and abnormal cilia. In patients in whom the clinical suspicion is high, but ciliary structure appears to be normal, fresh biopsy specimens can be examined for ciliary movement by video microscopy. However, this is only performed in few specialized centres in North America. Biopsy results are occasionally inconclusive, and the diagnosis may have to rest on clinical grounds. A negative biopsy should be viewed with suspicion when the child has the classical presentation of situs inversus totalis, chronic rhinorrhea and otorrhea, and chronic cough and sputum production.

Genetic analysis for several of the genes causing PCD, including DNAI1 and DNAH5, is now available. These genes cause abnormalities of the dynein arms and are responsible for approximately one-quarter of PCD cases.

Because sperm flagellae have a similar structure to respiratory cilia, it was thought that all males with PCD would be infertile, but we now know that this is not the case and a substantial minority of men with PCD are fertile. Semen analysis for assessment of sperm motility is recommended when the need arises. The ciliated cells lining fallopian tubes will also be affected, but there is limited evidence for infertility or ectopic pregnancies in women with PCD.

Because there are no specific therapies that will correct the underlying ciliary defect, treatments are directed to aiding clearance of mucus and managing respiratory infections and other complications. Daily chest physiotherapy is essential to delay the progression of lung disease. Aerosol bronchodilator therapy may be useful in some patients; the importance of exercise should be emphasized. Prolonged (three weeks) courses of oral antibiotics directed to the main infecting organisms should be given at the first sign of an increase in respiratory symptoms. Hospitalization for intravenous antibiotics may be necessary for troublesome cases. Consultation with a physiotherapist experienced in the various techniques for airway clearance can be invaluable. Inhaled corticosteroids and other asthma medications are not indicated in the child with PCD. Regular hearing assessments and monitoring by an otolaryngologist is necessary because of the complications associated with secretory otitis media, chronic middle-ear effusions and recurrent sinusitis. Although tympanostomy tubes are often inserted in these situations, the resulting chronic otorrhea in some patients may be unacceptable. It has been suggested that hearing aids may be preferable if effusions affect hearing to the degree that speech and educational development are impaired. In the majority of cases, hearing deficits improve in later childhood and, thus, hearing aids are not necessary. A discharging ear may have to be cleaned periodically; topical antibiotics are beneficial in some cases. Nasal discharge becomes less of a problem with time as the child learns to blow his or her nose, but the child and adult may always have a sniffly nose. Topical decongestants and steroids are rarely helpful. Patients with PCD require all the regular childhood immunizations as well as a pneumococcal vaccine and yearly influenza shots. Counselling against smoking, as well as exposure to second hand smoke and air pollutants is advised. Parents planning more children should be counselled regarding the recurrence risk of one in four births, as seen in autosomal recessive conditions.

Regular follow-up is necessary for the child with PCD because the condition is lifelong. The goal is to prevent chronic lung damage and bronchiectasis, as well as manage the associated complications of hearing loss and chronically discharging ears. Periodic review of the chest physiotherapy routine is necessary, as well as yearly or twice yearly chest radiographs, pulmonary function testing and hearing assessments. Sputum cultures can guide antibiotic choices. Routine care and monitoring can be provided by the primary care physician, as is the case for most chronic illnesses in childhood, but because of the rarity of PCD, patients are likely to benefit from periodic review and regular follow-up in a multidisciplinary clinic with special expertise in the disorder. There are many unanswered questions in PCD, including the loci of many of the causal genes and optimal treatment; patients may be invited to participate in research studies.

Many patients with PCD experience a normal or near-normal life expectancy. However, progressive bronchiectasis with loss of lung function leading to severe pulmonary disability and respiratory failure is a distinct possibility. Early diagnosis and institution of appropriate therapy is currently the best strategy to minimize lung disease and improve the overall prognosis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bush A, Cole P, Hariri M, et al. Primary ciliary dyskinesia: Diagnosis and standards of care. Eur Respir J. 1998;12:982–8. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.12040982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bush A, Chodhari R, Collins N, et al. Primary ciliary dyskinesia: Current state of the art. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92:1136–40. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.096958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES FOR PARENTS

- 1.Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario. Health information – CHEO immotile cilia syndrome (Kartagener’s syndrome, primary ciliary dyskinesia) <http://www.cheo.on.ca/english/disclaimer_ics.shtml> (Version current at August 28, 2008).

- 2.PCD Foundation. <http://www.pcdfoundation.org/> (Version current at August 28, 2008).