Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The importance of the teaching role of residents in medical education is increasingly being recognized. There are little data about how this role is perceived within training programs or how residents develop their teaching skills. The aims of the present study were to explore the perspectives of Canadian paediatric program directors and residents on the teaching role of residents, to determine how teaching skills are developed within these programs, and to identify specific areas that could be targeted to improve resident teaching skills and satisfaction.

METHODS:

Program directors and residents in Canadian paediatric residency programs were surveyed about the scope of teaching performed by residents, resident teaching ability and resources available for skill development.

RESULTS:

Responses were received from 11 of 13 program directors contacted. Nine programs agreed to have their residents surveyed, and 41% of residents in these programs responded. Directors and residents agreed that residents taught the most on general paediatric wards, and that medical students and residents were the most frequent recipients of resident teaching. While 72% of directors reported that instruction in teaching was provided, only 35% of residents indicated that they had received such training. Directors believed that residents needed improvement in providing feedback, while residents wanted help with teaching at the bedside, during rounds and in small groups. Teaching performance was included in rotational evaluations in most programs, but residents were often uncertain of expectations and assessment methods.

CONCLUSION:

There is a general consensus that residents play an important teaching role, especially on the inpatient wards. Residents’ ability to fill this role could be enhanced by clearer communication of expectations, timely and constructive feedback, and targeted training activities with the opportunity to practice learned skills.

Keywords: Medical education, Paediatrics, Residency

Abstract

HISTORIQUE:

On admet de plus en plus l’importance du rôle d’enseignement des résidents pour la formation en médecine. Il existe peu de données sur la perception de ce rôle au sein des programmes de formation ou sur la manière dont les résidents acquièrent leurs aptitudes à l’enseignement. La présente étude visait à explorer les perspectives des directeurs de programmes canadiens en pédiatrie et des résidents sur le rôle d’enseignement des résidents, à déterminer le mode d’acquisition des aptitudes à l’enseignement au sein de ces programmes et à établir des secteurs précis à cibler pour améliorer les aptitudes à l’enseignement et la satisfaction des résidents.

MÉTHODOLOGIE:

Les directeurs de programme et les résidents des programmes canadiens de résidence en pédiatrie ont fait l’objet d’une enquête sur la portée de l’enseignement effectué par les résidents, l’aptitude à l’enseignement des résidents et les ressources disponibles pour l’acquisition de ces aptitudes.

RÉSULTATS:

Onze des 13 directeurs de programme qui ont reçu l’enquête y ont répondu. Neuf programmes ont accepté que leurs résidents participent à l’enquête, et 41% des résidents de ces programmes ont répondu. Les directeurs et les résidents ont convenu que les résidents enseignaient surtout au service de pédiatrie générale et que les étudiants en médecine et les résidents étaient les principaux destinataires de l’enseignement des résidents. Tandis que 72% des directeurs ont indiqué que les résidents recevaient des directives sur l’enseignement, seulement 35% des résidents corroboraient avoir reçu une telle formation. Les directeurs étaient d’avis que les résidents devaient s’améliorer en matière de rétroaction, mais les résidents désiraient de l’aide pour l’enseignement au chevet du patient, les séances scientifiques et l’enseignement en petits groupes. La qualité d’exécution de l’enseignement faisait partie de l’évaluation des stages de la plupart des programmes, mais souvent, les résidents n’étaient certains ni des attentes, ni des modes d’évaluation.

CONCLUSION:

Selon le consensus, les résidents jouent un rôle d’enseignement important, notamment dans les services hospitaliers. Il serait possible d’améliorer les aptitudes à remplir ce rôle par une communication plus claire des attentes, des commentaires constructifs à point utile et des activités de formation ciblées donnant l’occasion d’exercer les aptitudes acquises.

Over the past several decades, considerable attention has been drawn to the importance of contributions of residents to the medical education system. Researchers have estimated that residents spend up to 25% of their time engaged in some type of teaching activity (1). Medical students believe that residents play a major teaching role in their clinical education (2,3). Surveys (4,5) of medical school faculty have also recognized the critical role of residents in medical education. Finally, observational studies (6) of clinical teaching behaviours have found that faculty and resident teaching strategies are often complementary. The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada has also endorsed the importance of resident teaching. Within the scholar role of the CanMEDS physician competency framework, it is expected that a specialist physician will be equipped to “facilitate the learning of patients, housestaff/students and other health professionals” (7).

As the awareness of the importance of resident teaching increases, it has been recognized that residents need to be provided with guidance and education about how to teach more effectively (8). Many residency programs in Canada and the United States have begun to implement a variety of programs to improve resident teaching skills (9–14). Evaluations of these programs have demonstrated that they can lead to higher scores on objective-structured teaching examinations (15), better performance during observed teaching sessions (16,17), and higher ratings from medical students and more junior residents (18–20).

Currently, there are little or no data available on the teaching activities of Canadian paediatric residents, nor is there much information on the presence of specific ‘teaching instruction’ within residency programs outside of those reported in the medical education literature. Within this context, the aims of the present study are to explore the perspectives of Canadian paediatric program directors and residents on the teaching roles of residents and the ability of residents to fill these roles, to determine the scope of resources available within training programs to help residents improve their teaching abilities, and to identify potential targets for intervention to improve resident teaching.

METHODS

The present study received ethics approval from the Research Ethics Board of the Montreal Children’s Hospital (Montreal, Quebec) and McGill University (Montreal, Quebec). It was funded by a grant from the Montreal Children’s Hospital Research Institute.

Study participants

Two groups were surveyed in the present study – paediatric residency program directors at all 13 paediatric training programs that participated in the 2004 Canadian Resident Matching Service (CaRMS) (the three francophone programs were not included), and all paediatric residents whose program directors agreed to allow their residents to be approached. Residents in subspecialty paediatric training programs were not included.

Surveys

Development

Two separate surveys were developed – one for program directors and one for residents. The primary domains of interest were demographic data (program and year of training), program director and resident perceptions of resident teaching roles, comfort and ability in different teaching situations, access to resources to improve teaching and targets for further training in this area. These were selected based on a review of the current literature on resident teaching and discussions with a number of residents and educators. Question formats included five-point Likert scales, ranking items from a list and multiple-choice with the option to choose more than one answer or add other responses. For questions asking about different teaching activities, short definitions were provided. Before implementation, surveys underwent pilot testing by several residents and one program director to ensure clarity and face validity.

Implementation

Program directors were contacted by e-mail to inform them of the present study, to invite their participation and to ask permission to survey residents in their programs. If they agreed to participate, they were directed to the on-line survey site, SurveyMonkey (SurveyMonkey.com, USA), to complete the questionnaire. If they agreed to have their residents participate, they were sent an introductory e-mail with links to the resident version of the questionnaire to distribute electronically among those in their program. Two reminder e-mails, spaced two to four weeks apart, were sent to programs that did not initially respond.

Statistical analysis

Data were transferred directly from the on-line survey tool, SurveyMonkey, to a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation, USA) for analysis. Descriptive statistics were calculated for questions related to demographics, resident teaching responsibilities and exposure to teaching improvement resources. For comparison of responses from residents at different levels of training, residents were stratified as either ‘junior’ (postgraduate year 1 [PGY-1] and PGY-2) or ‘senior’ (PGY-3 and higher). The Spearman rank-order coefficient (rs) was calculated to determine whether groups ranked topics differently. Narrative comments were analyzed thematically by the primary investigator (Dr Walton), and then reviewed by several other individuals familiar with the topic to identify issues that were not reflected in quantitative data. There were no disagreements regarding the major themes present in the narrative comments.

RESULTS

Overall, 11 of 13 program directors approached for this survey responded, and nine consented to have their residents surveyed. Of the program directors that did not consent to resident participation, one program director required that the project first be approved by the institutional ethics committee of that institution, but this could not be accomplished in a timely fashion. For other programs, no reasons were given. The nonparticipating programs were all medium-sized (approximately 16 to 24 residents), and were from various regions of Canada. The mean size of participating programs was 29.6 residents (range 13 to 56 residents), and the response rate by program ranged from 14.3% to 63.2%, with a median of 42.9%. Further demographic information about participating programs and residents can be found in Table 1. Data from resident surveys were pooled across all programs because the wide range of response rates precluded comparisons among programs. Small and unequal sample sizes, along with differing question formats did not permit statistical comparison of most resident and program director responses.

TABLE 1.

Demographic data

| Residency programs | n |

|---|---|

| Total contacted | 13 |

| Program directors responded | 11 |

| Agreed to resident participation | 9 |

|

Residents | |

| Total contacted | 237 |

| Completed surveys | 97 |

| Level of training of respondents | |

| PGY-1 | 34 |

| PGY-2 | 22 |

| PGY-3 | 20 |

| PGY-4 | 16 |

| PGY-5 or higher | 5* |

These residents were from Quebec, where general paediatrics is a five-year program. PGY Postgraduate year

All program directors and 73 of 97 residents believed that the inpatient general paediatric ward rotation was the most common setting for teaching by residents. Many residents also reported substantial teaching responsibilities (more than 1 h per week) on inpatient subspecialty rotations (16 of 97 residents) and in the emergency department (22 of 97 residents). Few residents reported spending more than 1 h per week in a specific teaching role in general paediatric (five of 97 residents) or subspecialty (six of 97 residents) clinics. When asked to select which groups were most commonly taught by residents, both program directors and residents chose other residents and senior medical students. A number of residents (19 of 97) also reported substantial involvement in teaching other professionals, and students of nursing and allied health professions.

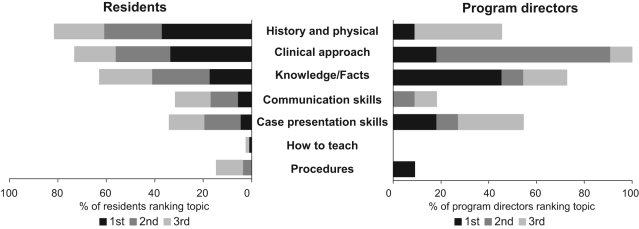

Program directors and residents had differing perspectives on what trainees learn from residents. When asked to rank a list of items, program directors rated approaches to clinical problems most highly, while residents believed that history and physical skills were most important (Figure 1 [rs=0.85; P<0.05]). When the resident rankings were stratified based on level of training, junior residents ranked communication skills significantly more highly than seniors, while senior residents assigned greater importance to approaches to problems (rs=0.9; P<0.05).

Figure 1).

Resident and program director rankings of domains most commonly taught by paediatric residents. Rankings differed significantly between groups (Spearman rank-order coefficient rs=0.85; P<0.05)

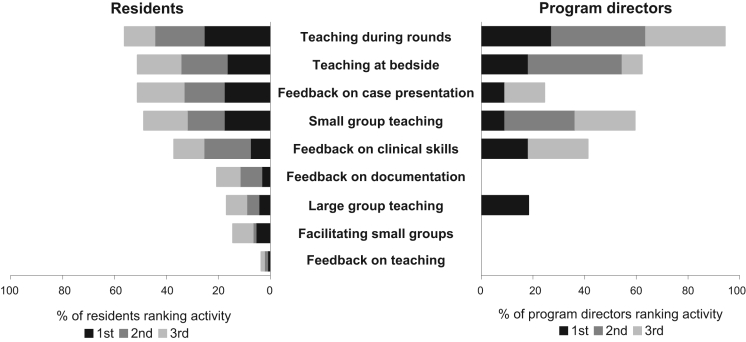

Program directors overwhelmingly agreed that residents were most experienced with teaching during rounds. Residents also reported considerable experience with teaching during rounds, but activities such as bedside teaching, small group facilitation and giving feedback on patient presentations were ranked similarly high (Figure 2). When data were stratified based on level of training, senior residents felt most experienced or capable teaching during rounds, while juniors ranked delivering teaching sessions to small groups most highly. When asked to select topics that would most benefit their current teaching practices, residents as a whole expressed interest in receiving additional instruction in teaching during rounds, bedside teaching and in giving feedback. Senior residents were more likely to express a preference for instruction in providing feedback, while juniors were more likely to want to improve their small-group teaching skills (rs=0.9; P<0.05).

Figure 2).

Resident and program director perspectives on teaching activities with which residents are most experienced or capable. Rankings differed significantly between groups (Spearman rank-order coefficient rs=0.85; P<0.05)

The majority of program directors reported that specific resources were available to residents to help improve teaching skills, but only one-third of residents recalled having received any specific training in teaching (Table 2). Interestingly, more junior residents reported exposure to specific training than senior residents (43.4% versus 29.0%). In all but one program, directors reported that teaching skills were included as a component of resident evaluations. In contrast, only 52.6% of residents were aware of this, and many reported receiving little or no feedback on their teaching skills (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Availability of interventions to improve resident teaching skills

| Program directors (data from 11 programs) | n |

|---|---|

| Specific resources provided to residents | 8 |

| Standardized courses, such as TIPS | 4 |

| Participation in faculty development workshops | 2 |

| Program-specific activities | |

| Workshops with active participation | 3 |

| Didactic sessions | 3 |

| Resident teaching skills evaluated each rotation | 10 |

| Evaluation of residents based on | |

| Feedback from students/residents | 7 |

| Observation by attending | 4 |

| Teaching station on an OSCE | 2 |

| No specific method | 1 |

|

Residents (data from 97 residents) | |

| Reported no exposure to resources | 64 |

| Reported any exposure | 33 |

| Workshop with active participation | 25 |

| Small group session | 16 |

| Lecture | 11 |

| Written information | 10 |

| Chief resident conference | 3 |

| Feedback received on teaching performance | |

| Verbal following teaching session | 38 |

| Written following teaching session | 13 |

| Verbal at end of rotation | 31 |

| Written at end of rotation | 24 |

| Verbal or written during six monthly reviews | 2 |

| Little or none | 31 |

Some respondents selected more than one option. OSCE Objective-structured clinical examination; TIPS Teaching Improvement Project System

Thematic analysis of narrative comments revealed several issues that were not specifically reflected in the questionnaire data. These included the importance of resident teaching within medical training, barriers to effective resident teaching and the desire by residents for more constructive feedback on their teaching skills. Representative comments are presented in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Themes emerging from narrative comments by residents

| Importance of resident teaching within medical training | “[The] quality of clerkship experience is often highly dependant on the residents working with the medical students at the time.” (PGY-1) |

| “I feel that enhancing teaching skills at the senior trainee level is essential to ensure that we are good educators when we become staff ourselves.” (PGY-3) | |

| “I believe teaching is an ethical responsibility for all people in [the] medical field.” (PGY-1) | |

| Barriers to effective teaching by residents | “Expectations are high. Often one’s confidence regarding teaching is low.” (PGY-2) |

| “There is a big time management issue to teaching – how to fit it into your own overwhelming workload…” (PGY-3) | |

| “Very little info is provided [about] what is expected in terms of teaching for students.” (PGY-2) | |

| “We don’t have the objectives for the rotation. We usually [just] teach about topics that interest us…” (PGY-2) | |

| “Students sometimes don’t appreciate the teaching that we do, which makes it more difficult to continue putting in the effort.” (PGY-2) | |

| Resident desire for more instruction and feedback on teaching skills | “… it is assumed that we will figure it out for ourselves.” (PGY-1) |

| “… teaching skills are generally passed on from the senior to the junior resident by example.” (PGY-3) | |

| “My teaching abilities have never been emphasized in my evaluations (whether good or bad, I don’t even know as no one has spoken to me about them).” (PGY-4) | |

| “It’s listed as part of the Can MEDS roles on our evaluation form, but I think the attending just puts down whatever they feel like.” (PGY-3) |

PGY Postgraduate year

DISCUSSION

The present study is the first to explore the teaching role of residents within Canadian paediatric residency programs from the perspectives of both residents and program directors. The study highlights areas of agreement, as well as areas in which program director and resident perspectives differ. There was general consensus among program directors and residents that the most significant teaching activities were directed toward medical students and residents on inpatient general paediatric services. Both groups believed that residents were generally well equipped to provide teaching during rounds in this setting. Program directors and residents also had similar perceptions of residents as primarily teachers of facts and clinical approaches. However, there was a striking mismatch between program director and resident perspectives regarding available resources to help residents improve their teaching skills. Many directors reported the existence of activities which residents were unaware of or did not recall participating in. Finally, while most programs included teaching performance on rotational evaluations, many residents perceived that they received insufficient information about what they should be teaching, and reported a lack of constructive feedback to help them improve their teaching performance.

Given that paediatric residents currently in Canadian programs spend between 12% and 28% of their time on general paediatric inpatient rotations (data from the 2008 CaRMS program information), it is not surprising that both residents and program directors recognized the importance of resident teaching in this setting. Similarly, when thinking about what it is that residents intentionally teach, it is not surprising that both program directors and residents ranked facts and clinical approaches highly. This is in contrast to published data (21), which have shown that much of what students learn from residents is not factual information but rather behaviours, such as communication transmitted via informal role modelling (21). In our study, fewer than one-fifth of program directors and one-third of residents recognized communication as one of the more important things learned from residents. This suggests a greater need for discussion and recognition of ‘teaching’ that occurs via informal and often unconscious role modelling.

There are several possible explanations for the mismatch between program director and resident perspectives about resources to improve resident teaching skills. In many programs, teaching improvement sessions are not held every year and thus, not all residents in a program may have been exposed at the time of the survey. It is also possible that residents may not have remembered a session that happened several years previously. Similarly, some programs have recently implemented sessions as part of the orientation for new residents, which could account for the fact that more junior residents reported exposure to resources than seniors. Finally, program directors may have reported interventions that had been developed in response to the new CanMEDS physician competency framework, but had not yet been fully implemented. In any case, the paucity of resources perceived by residents in general suggests that there is certainly room for improvement.

There are several limitations to the present study. Only the perspectives of program directors and residents within paediatric training programs were examined and thus, the results may not be applicable to those in other fields. Furthermore, responses were received from residents in only nine programs, and from only 41% of those residents; thus, these results may not reflect the general experiences of all Canadian residents. The retrospective nature of the present survey may have led to recall bias, resulting in either under-or over-reporting of the items of interest. Finally, it is a survey of resident and program director perceptions of resident teaching roles and ability only, so no conclusions can be drawn about the actual teaching abilities of Canadian paediatric residents.

CONCLUSIONS

The present study affirms the key teaching role that residents play in Canadian training programs, and offers the dual perspectives of program directors and residents at a variety of training levels. The differences in perspectives between program directors and residents identified highlight the need for clear communication between residents and program directors about issues and resources related to this role. Programs should develop more comprehensive curricula that address not only the teaching of clinical knowledge and factual information, but also the important roles that residents play in the socialization of medical students and other residents. These should be developed in consultation with residents, with recognition that residents at different levels may have different needs. Finally, if residents are going to continue to be evaluated on their teaching skills as part of in-training assessments, efforts should be made to develop specific expectations and to provide trainees with frequent, constructive feedback on their performance. Regular evaluations of resident teaching improvement programs based on trainee perceptions, as well as objective assessments of teaching performance, should be conducted to establish best practices and to continually improve the effectiveness of these programs.

REFERENCES

- 1.LaPalio LR. Time study of students and house staff on a university medical service. J Med Educ. 1981;56:61–4. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198101000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bing-You RG, Tooker J. Teaching skills improvement programmes in US internal medicine residencies. Med Educ. 1993;27:259–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1993.tb00266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Julian TM. A graduating medical school class evaluates their educational experience. WMJ. 1998;97:56–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morrison EH, Hollingshead J, Hubbell FA, Hitchcock MA, Rucker L, Prislin MD. Reach out and teach someone: Generalist residents’ needs for teaching skills development. Fam Med. 2002;34:445–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Busari JO, Scherpbier AJ, van der Vleuten CP, Essed GG. The perceptions of attending doctors of the role of residents as teachers of undergraduate clinical students. Med Educ. 2003;37:241–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tremonti LP, Biddle WB. Teaching behaviors of residents and faculty members. J Med Educ. 1982;57:854–9. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198211000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.RCPSC . CanMEDS 2000 – Skills for the New Millenium: Report of the Societal Needs Working Group. Ottawa: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrison EH, Shapiro JF, Harthill M. Resident doctors’ understanding of their roles as clinical teachers. Med Educ. 2005;39:137–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.02063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bharel M, Jain S. A longitudinal curriculum to improve resident teaching skills. Med Teach. 2005;27:564–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weissman MA, Bensinger L, Koestler JL. Resident as teacher: Educating the educators. Mt Sinai J Med. 2006;73:1165–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roberts KB, DeWitt TG, Goldberg RL, Scheiner AP. A program to develop residents as teachers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1994;148:405–10. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1994.02170040071012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Craig JL. Teacher training for medical faculty and residents. CMAJ. 1988;139:949–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bensinger LD, Meah YS, Smith LG. Resident as teacher: The Mount Sinai experience and a review of the literature. Mt Sinai J Med. 2005;72:307–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morrison EH, Rucker L, Boker JR, et al. A pilot randomized, controlled trial of a longitudinal residents-as-teachers curriculum. Acad Med. 2003;78:722–9. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200307000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaba ND, Blatt B, Macri CJ, Greenberg L. Improving teaching skills in obstetrics and gynecology residents: Evaluation of a residents-as-teachers program. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:87, e1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.James MT, Mintz MJ, McLaughlin K. Evaluation of a multifaceted “resident-as-teacher” educational intervention to improve morning report. BMC Med Educ. 2006;6:20. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-6-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D’Eon MF. Evaluation of a teaching workshop for residents at the University of Saskatchewan: A pilot study. Acad Med. 2004;79:791–7. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200408000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morrison EH, Rucker L, Boker JR, et al. The effect of a 13-hour curriculum to improve residents’ teaching skills: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:257–63. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-4-200408170-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wipf JE, Orlander JD, Anderson JJ. The effect of a teaching skills course on interns’ and students’ evaluations of their resident – teachers. Acad Med. 1999;74:938–42. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199908000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Busari JO, Scherpbier AJ, van der Vleuten CP, Essed GG. A two-day teacher-training programme for medical residents: Investigating the impact on teaching ability. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2006;11:133–44. doi: 10.1007/s10459-005-8303-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilkerson L, Lesky L, Medio FJ. The resident as teacher during work rounds. J Med Educ. 1986;61:823–9. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198610000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]