Abstract

Transplant immunosuppressants have been implicated in the increased incidence of non-melanoma skin cancer in transplant recipients, most of whom harbor considerable UVB-induced DNA damage in their skin prior to transplantation. This study was designed to evaluate the effects of two commonly used immunosuppressive drugs, cyclosporine A (CsA) and sirolimus (SRL), on the development and progression of UVB-induced non-melanoma skin cancer. SKH-1 hairless mice were exposed to UVB alone for 15 weeks, and then were treated with CsA, SRL, or CsA+SRL for 9 weeks following cessation of UVB treatment. Compared with vehicle, CsA treatment resulted in enhanced tumor size and progression. In contrast, mice treated with SRL or CsA+SRL had decreased tumor multiplicity, size, and progression compared with vehicle-treated mice. CsA, but not SRL or combined treatment, increased dermal mast cell numbers and TGF-β1 levels in the skin. These findings demonstrate that specific immunosuppressive agents differentially alter the cutaneous tumor microenvironment, which in turn may contribute to enhanced development of UVB-induced skin cancer in transplant recipients. Furthermore, these results suggest that CsA alone causes enhanced growth and progression of skin cancer, whereas co-administration of SRL with CsA causes the opposite effect.

INTRODUCTION

It is apparent that the immune system as a whole can both promote and antagonize tumor development (Balkwill and Mantovani, 2001; de Visser and Coussens, 2005). The balance between these two roles is influenced by the type of cancer; the stage of the cancer; the immune cell types involved; and external influences such as foreign pathogens, chemical agents, or medications. Inflammation has been implicated in enhanced carcinogenesis in a number of organs, including skin (Shacter and Weitzman, 2002; de Visser and Coussens, 2006; De Marzo et al., 2007). It has even been stated that the effects of inflammatory cells are as important to tumor development as alterations in oncogene and tumor-suppressor genes (Coussens and Werb, 2001).

Many studies have been conducted in vitro using cell lines and in vivo using chemically induced and orthotopic models to understand the influences of immune and resident skin cells on the development and progression of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Innate effectors such as neutrophils and mast cells have been strongly implicated in carcinogenesis due to their ability to promote inflammation (Coussens and Werb, 2001). Previously, we showed that enhanced neutrophil infiltration and activity in the dermis are highly correlated with increases in UVB-induced tumor numbers, and that reduction of inflammation using selective COX-2 inhibitors can reduce the tumor load by 50–70% (Wilgus et al., 2003). Others have demonstrated that the presence of tryptase-positive mast cells correlates with poor prognosis in cancer patients (Takanami et al., 2000; Ribatti et al., 2003), which is thought to be due to their role in angiogenesis and tumor metastases (Rojas et al., 2005; Welsh et al., 2005).

Many cytokines have been shown to be important positive and or negative mediators of cutaneous inflammation and skin carcinogenesis depending on the stage of carcinogenesis that they are present. For example, tumor-necrosis factor-α promotes cancer initiation but has no effect on progression (Suganuma et al., 1999), whereas transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) exerts potential pro- and anticarcinogenic effects during cancer initiation, but enhances progression at the later stages of carcinogenesis (Li et al., 2005). TGF-β1 has also been shown to cause inflammation when conditionally expressed in the skin of mice (Liu et al., 2001).

Much work has been done in characterizing the multifaceted interactions between immune cells and cancers, but few studies have addressed the effects of therapeutic immunosuppression (IS) on the changes in the skin resulting in increased development of non-melanoma skin cancer.

It is well established that solid-organ transplant recipients have a dramatically increased incidence of aggressive malignancies, especially cutaneous malignancies (DiGiovanna, 1998). Furthermore, the majority of organ transplant recipients (67%) are between the ages of 35–65 (based on Organ Procurement and Transplant Network data as of 23 March 2007) and therefore most likely have precancerous keratinocytes containing UVB-induced damage from years of sun exposure (Abdulla et al., 2005; Vanbuskirk et al., 2005). In fact, SCC is the most frequent skin cancer in the transplant patient population, and the disease in these patients is more aggressive than in the general population (Buell et al., 2005). This increase in SCC has been linked to the immunosuppressive agents given to solid-organ transplant recipients to prevent organ rejection (Otley and Maragh, 2005; Neuburg, 2007). Cyclosporine A (CsA), an older immunosuppressive drug, is a cyclic-peptide immunosuppressant that inhibits calcineurin and is reported to have procarcinogenic effects (Servilla et al., 1987; Tiu et al., 2006). Sirolimus (SRL), a newer drug, also known as rapamycin, is a macrolide immunosuppressant that acts through inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin. In addition to its use to prevent organ rejection, this drug is also currently under investigation as a chemopreventative agent based on reports of its antiangiogenic and growth-inhibitory effects (Euvrard et al., 2004).

This study was designed to model the clinical situation in which a patient with a history of sun exposure who, after receiving a transplant and beginning immunosuppressive treatment, avoids further sun exposure. Since UVB can induce and promote carcinogenesis, this study design removes the confounding effects of UVB-induced promotion on established tumors in an immunosuppressive milieu. Therefore, our study brings to light the effects of CsA and SRL on the development and progression of de novo UVB-induced cutaneous tumors. We found that CsA-treated mice had an increase in tumor size and progression associated with increased cutaneous proinflammatory mediators, which was not seen with SRL and was blocked when both agents were given in combination.

RESULTS

Tumor number, size, and total tumor burden

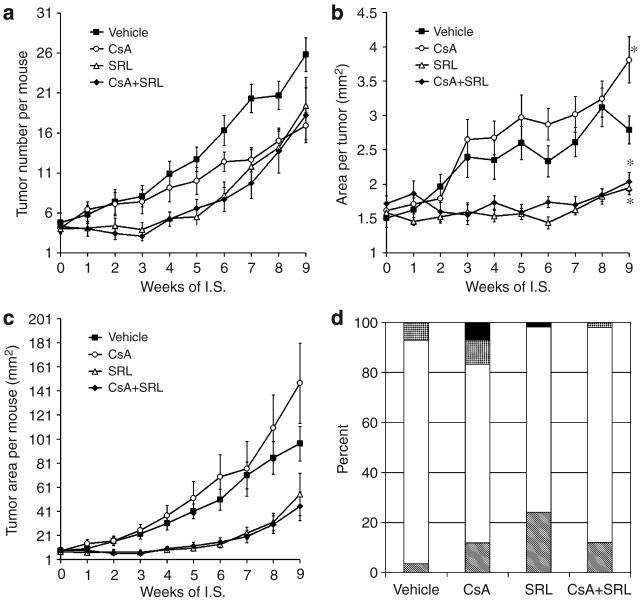

Upon initiation of immunosuppressive treatment, individual tumors were measured weekly for each mouse. The length and width of palpable lesions greater than 1mm in any direction were measured and included in the data set. All treatment groups had a mean tumor number of less than five tumors per mouse at the beginning of IS treatment. Tumor number in the vehicle group steadily increased over the entire treatment period. There were no differences in tumor number between SRL and CsA+SRL treatment groups, but both were lower than that for vehicle treatment at all time points (Figure 1a). At early time points of IS, between weeks 2 and 6, CsA-treated mice had more tumors than SRL- and CsA+SRL-treated mice. Using linear regression analysis, the rate of increase for tumor number was significantly decreased in all three treatment groups compared with the vehicle (P<0.03; Figure 1a). When tumors ≥2mm in diameter were considered, the vehicle and CsA treatment groups were quite similar, with a mean of 7.7 and 6.1 tumors per mouse, whereas both SRL and CsA+SRL treatment groups were dramatically lower, with only 1.5 and 1.7 tumors per mouse, respectively (data not shown). Furthermore, only one in 10 mice had a tumor over 9mm2 in the SRL and CsA+SRL treatment groups, whereas CsA and vehicle treatment groups had means of 2.5 and 2.1 large tumors per mouse, respectively (data not shown). SRL and CsA+SRL treatment groups had significant decreases in average tumor size compared with vehicle as early as week 5 of IS (P<0.03; Figure 1b). By 9 weeks of IS, the mean area per tumor for the CsA treatment group was significantly larger than that for the vehicle treatment group (P<0.01). The overall effects of the IS regimes can be seen in Figure 1c, showing total tumor burden per mouse.

Figure 1. Tumor progression and grading.

Length and width of dorsal neoplastic lesions were measured weekly for 9 weeks following initiation of IS for calculation of tumor number per mouse (a), mean area per tumor (length×width; b), and total tumor burden per mouse (c). At week 9 of IS, the mean tumor size for CsA-treated mice was significantly larger than that of vehicle-treated mice (*P<0.01), whereas SRL and CsA+SRL treatment tumors were significantly smaller than due to vehicle treatment (*P<0.03). Data points are mean±SEM. Tumors were graded from each treatment group, vehicle (n=56), CsA (n=42), SRL (n=54), and CsA+SRL (n=50), were graded as follows: hyperplasia (striped), papilloma (white), MISCC (speckled), or SCC (black). Percentages of each grade of tumor are reported in panel (d).

Tumor and lymph node histological grading

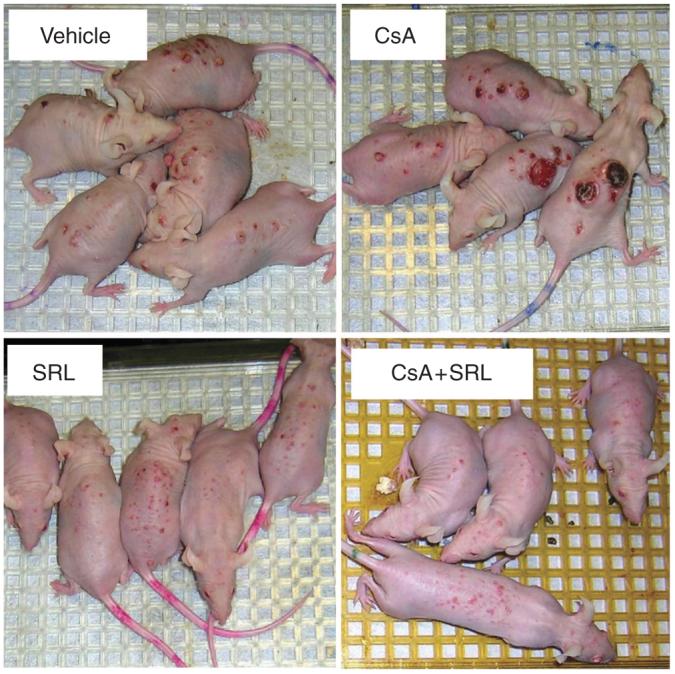

In all, 56, 42, 54, and 50 tumors from the vehicle, CsA, SRL, and CsA+SRL treatment groups, respectively, were graded histologically by a board certified veterinary pathologist (DF Kusewitt). Figure 1d shows the results as the percentage of tumors in each grade. The majority of tumors in each group were papillomas. Four microinvasive SCC (MISCCs) (7% of vehicle tumors graded) were found in the vehicle treatment group. SRL and CsA+SRL treatment groups had similar patterns, with only one SCC (2%) and one MISCC (1.85%), respectively. Mice treated with CsA developed the most aggressive tumors, with a total of three SCCs (7%) and four MISCCs (9%). Figure 2 shows representative pictures of tumor-bearing mice from each group immediately preceding killing.

Figure 2. Skin tumor formation on representative mice from each treatment group.

After week 24 of the study, immediately before mice were killed, photographs of representative mice from each of the treatment groups were taken.

Axillary and inguinal lymph nodes were formalin fixed, paraffin embedded, and hematoxylin and eosin-stained to be examined histologically for metastatic SCC. No metastatic cells were identified in the draining lymph nodes, but it was observed that the majority of lymph nodes from only the CsA-treated mice exhibited granulomatous lymphadenitis, characterized by presence of numerous macrophages and occasional multinucleated giant cells (data not shown).

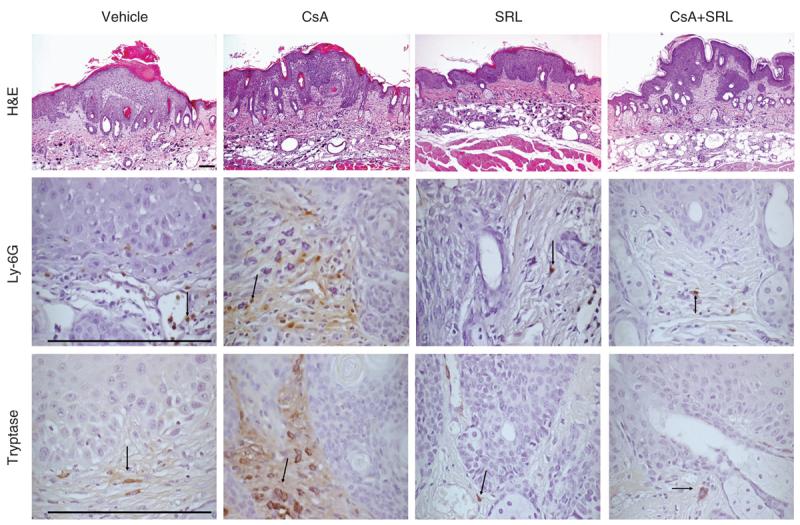

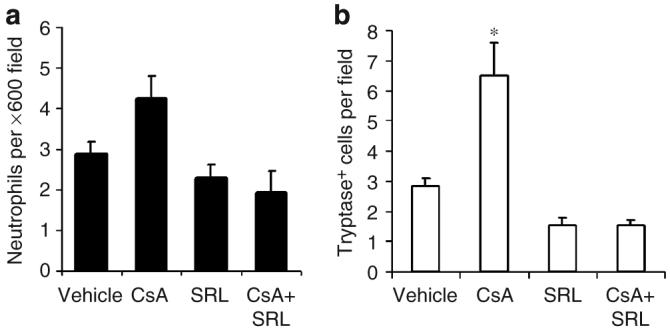

Identification of dermal infiltrative immune cells

We examined paratumoral dermis for neutrophil and mast cell presence. Immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated that there was a trend toward increased dermal neutrophil infiltration in CsA-treated mice, but this increase did not reach significance compared with vehicle-treated mice (Figures 3b and 4a). A significant increase in the number of tryptase-positive mast cells was seen in paratumoral dermis of CsA-treated mice compared with vehicle-, SRL-, and CsA+SRL-treated mice (Figures 3c and 4b; P<0.001). Both SRL and CsA+SRL treatment groups showed presence of reduced paratumoral tryptase-positive mast cells, but this difference was not significant (P=0.3).

Figure 3. Tumor-associated immune cell immunodetection.

Representative pictures of papilloma histology and histological detection of immune cells surrounding papillomas. The top row depicts representative pictures of formalin-fixed hematoxylin and eosin-stained papillomas (original magnification ×100); the middle row depicts tryptase-positive mast cells (original magnification ×600); and the bottom row depicts paratumoral Ly-6G-positive neutrophils (original magnification ×600). All immunohistochemical assays were developed with diaminobenzidine (brown) and counterstained with hematoxylin (blue).

Figure 4. Tumor-associated immune cell quantification.

Tumor sections were stained immunohistochemically for neutrophils (a) and tryptase-positive mast cells (b). The mean number of cells from five fields (original magnification ×600) in the paratumoral dermis were counted. Bars represent mean+SEM. CsA treatment resulted in a significant increase in tryptase-positive mast cells (*P<0.001).

Effect of immunosuppressive treatment on cutaneous cytokine levels

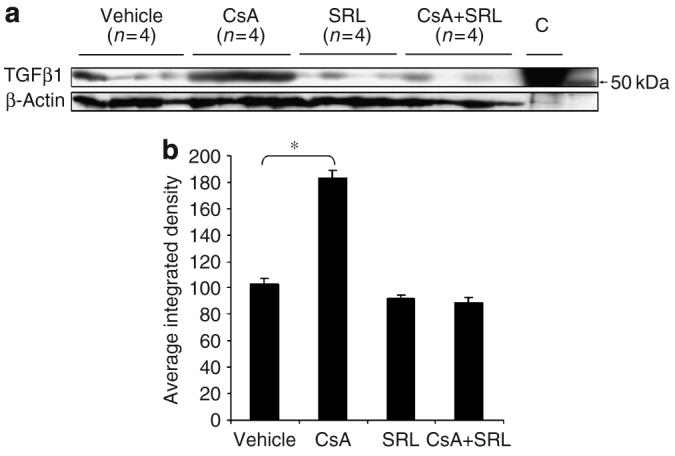

Whole-dorsal skin proTGF-β1 protein levels were assessed by western immunoblot (Figure 5a) and quantitated (Figure 5b). ProTGF-β1 level was significantly increased in CsA-treated dorsal skin compared with that in vehicle-treated skin (P<0.001). ProTGF-β1 levels decreased slightly in SRL and CsA+SRL-treated dorsal skin compared with that in vehicle-treated skin, although this was not statistically significant (P=0.57; Figure 5b).

Figure 5. Dorsal-skin TGF-β1 content.

Total protein was isolated from pulverized mouse dorsal skin and samples were analyzed by immunoblotting for TGF-β1 content; “C” is the control peptide purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (a). The exposed film was digitized and ImageJ was used to determine the integrated density of each band. The mean density+SEM (n=4) is shown ((b) *P<0.001).

DISCUSSION

Our study was designed to model the scenario in which cancer induction and promotion have occurred prior to IS, in order to begin to understand the changes in the immune system–skin cancer interactions under the influences of two prevalent and very different immunosuppressive drugs. Our findings support data from previous studies demonstrating that CsA treatment causes an increase in tumor size and progression (Servilla et al., 1987; Tiu et al., 2006), in association with increased expression of innate proinflammatory immune markers. We have also shown that SRL treatment reduced tumor number size and progression compared with vehicle treatment, and these effects were sufficient to block the changes brought about by CsA when the two drugs were given simultaneously.

In this study, we have shown that in our model we see this enhanced growth in terms of increased tumor size, but we also see an unexpected reduction in tumor number. This may be explained by the cessation of UVB irradiation 9 weeks prior to killing. Recently, Duncan et al. (2007) showed in a similar model that, with concurrent immunosuppression and UVB exposure, CsA treatment resulted in a larger number of tumors. We have not yet been able to clearly dissect out whether the changes in tumor size resulted from the action of CsA on the tumor cells themselves or indirectly via alterations in the immune system or both. However, in this study, the observed increase in tumor growth caused by CsA was also associated with mast cell infiltration and TGF-β production. These changes demonstrate alterations in the immune response that have been highly associated with increased tumor progression and poor patient prognosis (Robson et al., 1996; Ribatti et al., 2003; Leivonen and Kahari, 2007). Mast cells are a source of tumor-promoting paracrine factors and have been shown to play a role in tumor metastases (Rojas et al., 2005). Tryptase itself has been shown to cleave extracellular substrates, as well as act as an epithelial growth factor (Payne and Kam, 2004). This suggests that had we been able to continue treatment beyond 25 weeks, we may have seen an increase in metastatic lesions in the CsA-treated group. The lack of metastases is not surprising, since even with continued UV exposure we do not see metastases in immunocompetent mice in this mouse model until after 30 weeks.

While the precise mechanisms by which it works are not yet clear, TGF-β has been implicated in epithelial tumor progression. A recent study by Byrne et al. (2008) demonstrated that transfecting a murine regressing skin tumor with TGF-β enabled the tumors to grow progressively. TGF-β1 has been shown to promote inflammation (Liu et al., 2001) in the skin as well as epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (Han et al., 2005), important components of the tumorigenesis process. We are not the first to find a link between CsA treatment, increased levels of TGF-β and tumor growth. Hojo et al. reported that CsA treatment enhanced adenocarcinoma growth in immunodeficient severe combined immunodeficient-beige mice and that anti-TGF-β antibodies prevented CsA-induced increases in metastases (Hojo et al., 1999). They concluded that CsA-induced TGF-β production was involved in the ability of CsA to promote cancer progression. In this study, we detected increased TGF-β1 levels in the skin of mice with tumors of higher grade; however, we were not able to isolate the source of the TGF-β1, which can be produced by many cell types, including mast cells and keratinocytes. Further studies will be designed to identify the source of this cytokine in our model.

The ability of SRL to block the pro-tumor effects of CsA in this model when given in combination, are not surprising considering SRL has been shown to reduce growth of nonmelanoma skin cancer (Brown et al., 2006; Khariwala et al., 2006). Other groups have also shown an ability of SRL to reduce tumor growth in the presence of CsA (Silva et al., 2004).

In conclusion, we have shown important differences in the microenvironment of tumors isolated from the various IS treatment groups. These data support the theory that specific immunosuppressants differentially contribute to the skin carcinogenesis process and suggest that combined CsA and SRL suppressive therapy for solid-organ transplant recipients may be beneficial with regards to non-melanoma skin cancer development. More surprisingly, our findings suggest that, even without continued UVB exposure, treatment with CsA can cause changes in the skin that lead to increased growth and progression of UVB-induced skin cancer, and suggest that the skin of patients on CsA may need to be even more closely monitored than previously believed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and experimental design

Female SKH-1 hairless mice (6–8 weeks, 26–30 g) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) and housed in a facility approved by the American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. Water (containing Baytril) and food were given ad libitum. Animals were irradiated thrice weekly on nonconsecutive days for 15 weeks. Phillips FS40 UVB bulbs (American Ultraviolet Company, Murray Hill, NJ) with Kodacel filters (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY) were used to deliver 2240 Jm−2 UVB per exposure as determined by a UVR meter equipped with a UVB sensor (UVP Inc., Upland, CA). The UVB output was monitored biweekly to ensure consistent exposure throughout the experiment. This dose of UVB has been determined to be one minimal erythemic dose in our laboratory. After 15 weeks, UVB treatments were terminated and mice were assigned to one of four treatment groups: CsA alone (20 mgkg−1, n=8), SRL alone (2 mgkg−1, n=10), CsA+SRL (10 and 2 mg kg−1, respectively, n=10), or vehicle control (n=10), so that each group contained the same total number of tumors. IS or vehicle treatment was administered intraperitoneally daily for 9 weeks. An injectable form of CsA, Sandimmune (Novartis, Basel, Switzerland), and SRL (Rapamycin; LC Laboratories Inc., Woburn, MA) were used. The vehicle control was composed of 350mgml−1 cremophor EL, 37.5% ethyl alcohol, and 0.2% DMSO, in phosphate-buffered saline. The area (length×width) of individual tumors on each mouse was measured weekly to quantify tumor number, size, and total tumor area. Only tumors ≥1mm in any direction were included in the data set. At the end of 24 weeks and 24 hours after the final immunosuppressive treatment, mice were killed by lethal inhalation of carbon dioxide.

Sample preparation

Immediately after mice were killed, tumors were excised individually. Six tumors (two small, two medium, and two large) per mouse were selected based on the size range within each treatment group. Tumors were excised with surrounding uninvolved skin, and either frozen in OCT or fixed for 2 hours in 10% neutral buffered formalin and paraffin-embedded. After removal of all remaining tumors, “tumor-free” dorsal skin was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen for analysis of cytokine content. Axillary and inguinal lymph nodes were formalin fixed overnight and paraffin-embedded.

Tumor and lymph node grading

Sections of paraffin-embedded tumors (5-μm thick) and frozen tumors were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Tumor sections were graded in a blinded manner by a board certified veterinary pathologist (DF Kusewitt). Grades were assigned as follows: hyperplasia, papilloma, MISCC, or fully invasive SCC. Papillomas were exophytic tumors showing no evidence of stromal invasion and ranged from epithelium without a pronounced papillary pattern to having a well-differentiated papillary mass with a few finger-like projections of atypical cells at the base of the mass. MISCCs were categorized by penetration into the dermis. Only tumors that invaded all the way to the panniculus carnosus and had a more endophytic appearance, with stromal invasion evidenced by loss of basement membrane continuity and development of an inflammatory stromal response, were classified as fully invasive SCCs. Hyperplasias and papillomas were considered benign, whereas SCCs and MISCCs were considered malignant. Axillary and inguinal lymph nodes were formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded. Sections of axillary and inguinal lymph nodes (5-μm thick) were hematoxylin and eosin-stained and examined histologically for metastatic SCCs.

Antibodies

Rat anti-mouse Ly-6G was purchased from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). Mouse anti-human mast cell tryptase was purchased from Chemicon (Temecula, CA). Rabbit anti-mouse TGF-β1 was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Rabbit anti-rat and goat anti-rabbit biotinylated secondary antibodies were purchased from Pierce (Rockford, IL).

Immunohistochemistry

Tryptase-positive mast cells were detected using the Mouse on Mouse (MOM) detection kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Sections (5-μm thick) were cut from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded papillomas from each mouse. Sections were rehydrated by washing in Clearite, and then in a series of graded ethanol washes ending in water. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% H2O2 in methanol for 10 minutes, followed by a 1-hour incubation in MOM blocking buffer. Sections were incubated with mouse anti-tryptase antibody, in MOM diluent for 1 hour at room temperature, and then treated for 30 minutes with MOM biotinylated anti-mouse secondary antibody in MOM diluent. A 15-minute incubation with Vectastain elite ABC reagent (Vector Laboratories) was followed by development with diaminobenzidine. Samples were counterstained with Meyer's hematoxylin, dehydrated through a graded series of ethanol washes with a final wash in Clearite, and mounted with Vectamount (Vector Laboratories). Detection of Ly-6G+ Cells, as a marker for neutrophils, was performed as described previously by Wilgus et al. (2003). The mean number of cells per field was determined by counting five fields (original magnification ×600) within the papillomas or in the paratumoral dermis.

TGF-β1 content

ProTGF-β1 was detected by western immunoblot analysis. Briefly, 50 μg of total protein from whole-back skin was electrophoresed under reducing conditions with Laemmli buffer (BioRad, Hercules, CA) in a 12.5% criterion polyacrylamide gel (BioRad). The protein was transferred, via electrophoresis, to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Nonspecific binding was blocked with 5% BSA in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20 and incubated with anti TGF-β1 antibody over night at 41°C. After rinsing in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20, the membrane was incubated with Pierce horse-radish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody for 1 hour. The immunocomplex was detected with super signal pico chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce) and was exposed to BioMax film (Kodak).

Statistics

Linear regression modeling was used to compare the shift and slope of the tumor number and total average tumor area over time. Data for these tests was transformed with square root and natural logarithm, respectively, and fitted to a model with the equation. Y =β0 +β1W+β2ICsA +β3ISRL +β4ICsA +SRLβ5WICsA+β6WISRL +β7WICsA +SRL, where W=weeks of treatment and I =binomial indicator variable (that is, Icsa =1 if CsA was used and 0 if CsA was not used). General linear modeling with Dunnett's method and α =0.05 was used for all other comparisons. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS version 16.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: NIH grant number 5R01CA109204-03

This work was performed in Columbus, Ohio, USA

Abbreviations

- CsA

cyclosporine A

- IS

immunosuppression

- MISCC

microinvasive squamous cell carcinoma

- MOM

Mouse on Mouse

- SCC

squamous cell carcinoma

- SRL

sirolimus (aka rapamycin)

- TGF-β1

transforming growth factor-β1

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors state no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Abdulla FR, Feldman SR, Williford PM, Krowchuk D, Kaur M. Tanning and skin cancer. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:501–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2005.00129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet. 2001;357:539–45. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RE, Zhang PL, Lun M, Zhu S, Pellitteri PK, Riefkohl W, et al. Morphoproteomic and pharmacoproteomic rationale for mTOR effectors as therapeutic targets in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2006;36:273–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buell JF, Hanaway MJ, Thomas M, Alloway RR, Woodle ES. Skin cancer following transplantation: the Israel Penn International Transplant Tumor Registry experience. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:962–3. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.12.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne SN, Knox MC, Halliday GM. TGFbeta is responsible for skin tumour infiltration by macrophages enabling the tumours to escape immune destruction. Immunol Cell Biol. 2008;86:92–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammatory cells and cancer: think different! J Exp Med. 2001;193:F23–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.6.f23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Marzo AM, Platz EA, Sutcliffe S, Xu J, Gronberg H, Drake CG, et al. Inflammation in prostate carcinogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:256–69. doi: 10.1038/nrc2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Visser KE, Coussens LM. The interplay between innate and adaptive immunity regulates cancer development. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2005;54:1143–52. doi: 10.1007/s00262-005-0702-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Visser KE, Coussens LM. The inflammatory tumor microenvironment and its impact on cancer development. Contrib Microbiol. 2006;13:118–37. doi: 10.1159/000092969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiGiovanna JJ. Posttransplantation skin cancer: scope of the problem, management, and role for systemic retinoid chemoprevention. Transplant Proc. 1998;30:2771–5. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(98)00806-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan FJ, Wulff BC, Tober KL, Ferketich AK, Martin J, Thomas-Ahner JM, et al. Clinically relevant immunosuppressants influence UVB-induced tumor size through effects on inflammation and angiogenesis. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:2693–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.02004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Euvrard S, Ulrich C, Lefrancois N. Immunosuppressants and skin cancer in transplant patients: focus on rapamycin. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:628–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2004.30148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han G, Lu SL, Li AG, He W, Corless CL, Kulesz-Martin M, et al. Distinct mechanisms of TGF-beta1-mediated epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and metastasis during skin carcinogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1714–23. doi: 10.1172/JCI24399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hojo M, Morimoto T, Maluccio M, Asano T, Morimoto K, Lagman M, et al. Cyclosporine induces cancer progression by a cell-autonomous mechanism. Nature. 1999;397:530–4. doi: 10.1038/17401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khariwala SS, Kjaergaard J, Lorenz R, Van Lente F, Shu S, Strome M. Everolimus (RAD) inhibits in vivo growth of murine squamous cell carcinoma (SCC VII) Laryngoscope. 2006;116:814–20. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000210544.64659.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leivonen SK, Kahari VM. Transforming growth factor-beta signaling in cancer invasion and metastasis. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:2119–24. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li AG, Lu SL, Han G, Kulesz-Martin M, Wang XJ. Current view of the role of transforming growth factor beta 1 in skin carcinogenesis. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2005;10:110–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1087-0024.2005.200403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Alexander V, Vijayachandra K, Bhogte E, Diamond I, Glick A. Conditional epidermal expression of TGFbeta 1 blocks neonatal lethality but causes a reversible hyperplasia and alopecia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:9139–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161016098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuburg M. Transplant-associated skin cancer: role of reducing immunosuppression. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2007;5:541–9. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2007.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otley CC, Maragh SL. Reduction of immunosuppression for transplant-associated skin cancer: rationale and evidence of efficacy. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:163–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne V, Kam PC. Mast cell tryptase: a review of its physiology and clinical significance. Anaesthesia. 2004;59:695–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.03757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribatti D, Ennas MG, Vacca A, Ferreli F, Nico B, Orru S, et al. Tumor vascularity and tryptase-positive mast cells correlate with a poor prognosis in melanoma. Eur J Clin Invest. 2003;33:420–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2003.01152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson H, Anderson E, James RD, Schofield PF. Transforming growth factor beta 1 expression in human colorectal tumours: an independent prognostic marker in a subgroup of poor prognosis patients. Br J Cancer. 1996;74:753–8. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas IG, Spencer ML, Martinez A, Maurelia MA, Rudolph MI. Characterization of mast cell subpopulations in lip cancer. J Oral Pathol Med. 2005;34:268–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2004.00297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servilla KS, Burnham DK, Daynes RA. Ability of cyclosporine to promote the growth of transplanted ultraviolet radiation-induced tumors in mice. Transplantation. 1987;44:291–5. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198708000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shacter E, Weitzman SA. Chronic inflammation and cancer. Oncology (Williston Park) 2002;16:217–26. 229; discussion 230–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva SL, Silva SF, Farias IN, Mota RS, Carvalho RA, Moraes MO, et al. Rapamycin even when combined with cyclosporine attenuates tumor growth but does not induce regression of established walker sarcomas. Transplant Proc. 2004;36:934–7. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.03.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suganuma M, Okabe S, Marino MW, Sakai A, Sueoka E, Fujiki H. Essential role of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) in tumor promotion as revealed by TNF-alpha-deficient mice. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4516–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takanami I, Takeuchi K, Naruke M. Mast cell density is associated with angiogenesis and poor prognosis in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2000;88:2686–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiu J, Li H, Rassekh C, van der Sloot P, Kovach R, Zhang P. Molecular basis of posttransplant squamous cell carcinoma: the potential role of cyclosporine a in carcinogenesis. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:762–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000205170.24517.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanbuskirk A, Oberyszyn TM, Kusewitt DF. Depletion of CD8+ or CD4+ lymphocytes enhances susceptibility to transplantable ultraviolet radiation-induced skin tumours. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:1963–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh TJ, Green RH, Richardson D, Waller DA, O'Byrne KJ, Bradding P. Macrophage and mast-cell invasion of tumor cell islets confers a marked survival advantage in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8959–67. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.4910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilgus TA, Koki AT, Zweifel BS, Kusewitt DF, Rubal PA, Oberyszyn TM. Inhibition of cutaneous ultraviolet light B-mediated inflammation and tumor formation with topical celecoxib treatment. Mol Carcinog. 2003;38:49–58. doi: 10.1002/mc.10141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]