Abstract

Background

Pathologic differences have been reported among breast tumors when comparing ethnic populations. Limited research has been done to evaluate the ethnic-specific relationships between breast cancer risk factors and the pathologic features of breast tumors.

Methods

Given that genetic variation may contribute to ethnic-related etiologic differences in breast cancer, we hypothesized that tumor characteristics differ according to family history of breast cancer among Hispanic and non-Hispanic White (NHW) women. Logistic regression models were used to compute odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) to assess this relationship in the population-based, case-control 4-Corners Breast Cancer Study (1,537 cases and 2,452 controls).

Results

Among Hispanic women, having a family history was associated with a 2.7-fold increased risk of estrogen receptor (ER) negative (95% CI, 1.59-4.44), but not ER positive tumors (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.71-1.54) when compared with women without breast cancer. In contrast, there was an increased risk for ER positive (OR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.50-2.38) and a marginally significant increased risk for ER negative tumors (OR, 1.41; 95% CI, 0.92-2.17) among NHW women. When comparing tumor characteristics among invasive cases, those with a family history also had a significantly higher proportion of ER negative tumors among Hispanics (39.2% versus 25.8%; P = 0.02), but not among NHWs (16.3% versus 21.1%; P = 0.13).

Conclusions

These results may reflect ethnic-specific predisposing genetic factors that promote the development of specific breast tumor subtypes, and emphasize the importance of evaluating the relationship between breast cancer risk factors and breast tumor subtypes among different ethnic populations.

Introduction

Disparities in breast cancer incidence rates, tumor characteristics, and survival have been observed among ethnic populations within the United States (1-8). For example, Hispanic women have an overall lower incidence rate of breast cancer compared with non-Hispanic White (NHW) women, yet they experience a higher risk of mortality after diagnosis (2, 5-7, 9). Pathologic differences among breast tumors have also been reported when comparing these populations (1, 4, 7, 9, 10). Ethnic disparities in breast cancer incidence and survival rates have been attributed to biological, cultural, and social factors. Although much emphasis has been placed on the role of social and cultural factors in explaining these differences (e.g., access to health care and screening practices; refs. 11-13), there is now increasing evidence to support the role of biological factors in ethnic disparities (14, 15). It was recently shown that Hispanic women were more likely to have tumor characteristics associated with poorer prognosis compared with NHW women despite equal access to health care services, specifically later stage disease, larger and poorly differentiated tumors, and estrogen receptor negative tumors (15). Given the disparities in breast cancer outcomes and tumor characteristics, it is possible that breast cancers among Hispanics, as well as other ethnic populations, comprise distinct subtypes within the etiologic spectrum of breast tumors.

Breast cancer subtypes defined by estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) status are known to have different clinical and pathologic features. Some epidemiologic studies show that these subtypes also have different risk factor profiles, providing additional evidence that these are etiologically distinct subtypes (16, 17). There is a growing body of literature to reflect the pathologic differences in breast tumors across ethnic groups, yet limited research has been done to evaluate the ethnic-specific relationships between breast cancer risk factors and breast cancer, particularly with respect to the pathologic characteristics of breast tumors.

Family history of breast cancer is a well-established and relatively prominent breast cancer risk factor, in spite of the fact that only 5% to 10% of breast cancers are associated with known genetic causes, e.g., BRCA mutations (18). Genetic variation in breast cancer susceptibility across ethnic populations is one plausible biological contributor to ethnic disparities in breast cancer outcomes. Given the potential contribution of genetic factors to the risk associated with family history (19), genetic factors that predispose to breast cancer may differ among ethnic populations and may be reflected by ethnic differences in familial risk of breast cancer subtypes. Furthermore, tumors that are the consequence of certain predisposing genetic factors may share similar pathologic characteristics. To gain insight into the potential ethnic-specific genetic component of breast cancer susceptibility, we used the 4-Corners Breast Cancer Study population to examine the relationship between family history of breast cancer and the pathologic characteristics of tumors among Hispanics and NHW women. To our knowledge, this study represents one of the first studies to explore this relationship among one of the largest study populations that includes Hispanic women.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

The 4-Corners Breast Cancer Study is a population-based, case-control study of breast cancer designed to investigate diet, lifestyle, and genetic factors that contribute to disparities in breast cancer outcomes observed between non-Hispanic and Hispanic women. Nearly one third of the study is Hispanic by self-report. The methods for selection, recruitment, and interview of subjects have been previously described in detail (20). Briefly, women who were 25 to 79 y of age at breast cancer diagnosis (or date of selection for controls) were recruited from the Southwest United States (Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah) during the years 2000 to 2005. Cases with a breast cancer diagnosed from October 1999 to May 2004 were identified through state-wide cancer registries. All Hispanic cases, and an age-matched sample of NHW cases, were selected. Hispanic ethnicity was initially identified through the cancer registry or by surname using the Generally Useful Ethnic Search System (21) algorithm. Controls were frequency-matched to cases on age and ethnicity. Control subjects less than 65 y of age were randomly selected from computerized driver’s license lists in New Mexico and Utah, and from commercially available lists in Arizona and Colorado, whereas subjects ages ≤65 y were selected from the Center for Medicare Studies lists in all centers. Study participation has been reported on in detail elsewhere (22). Among all selected subjects, we were able to contact 75% of Hispanic cases, 66% of Hispanic controls, 85% of NHW cases, and 75% of NHW controls. Cooperation rates were 55% for Hispanic and 64% for NHW cases, and 35% for Hispanic and 47% for NHW controls. Participants and nonparticipants were similar with respect to characteristics influencing participation (23). All aspects of the study were conducted in accordance with the research protocols for human subjects approved at each institution.

The subjects completed an interviewer-administered in-person computer-assisted questionnaire, which included questions regarding diet, physical activity, family history, reproductive history, and other breast cancer risk factors. The questions referred to exposures 1 y before diagnosis for cases and 1 y before selection for the study for controls. Women were asked about their first-degree family history of cancer. They reported the current vital status and the age of the relative at cancer diagnosis. A first-degree relative is defined as a mother, father, sister, brother, daughter, or son (blood relation). For this analysis, we excluded all secondary cases of primary breast cancer (n = 98 NHW and 48 Hispanic), women who did not know their family history (n = 51 NHW and 37 Hispanic), and women who did not self-report as being primarily of White or Hispanic ethnicity (n = 36). A total of 9 women reported a family history of breast cancer in a male relative, and these women were included in the analysis.

Data describing tumor characteristics, such as stage, grade, histology, and ER and PR status, were obtained through the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) cancer registry or the state tumor registry database. Cases diagnosed before 2001 were coded according to the second edition of the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O-2), and cases diagnosed from 2001 onward were coded according to the ICD-O-3. The histologic types were grouped accordingly: ductal carcinoma (8230, 8500, 8521, 8523), lobular carcinoma (8520, 8524), ductal/lobular (8522), all others, and unknown. Tumor stage classifications were based on SEER summary stage codes according to the 1977 definitions for cases diagnosed before 2001 or the 2000 definitions for cases diagnosed from 2001 and on. ER and PR status were recorded as positive, negative, or unknown (test not done, borderline, or results not entered in chart) based on laboratory results from medical records at the time of data collection by the state tumor registry. Women diagnosed with either in situ or stage unknown breast cancer (n = 328 NHW and 162 Hispanic), or missing data on ER status (n = 254 NHW and 138 Hispanic) were excluded.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.1 (SAS Institute). Logistic regression models were used to compute the ethnic-specific odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for the association between family history and breast cancer risk according to ER status. Positive family history was defined as any first-degree relative who was diagnosed with breast cancer. The interaction between family history and ethnicity on ER-defined breast cancer risk was evaluated by creating cross-product variables in ethnic-combined regression models.

The following potential confounding variables were adjusted for in the multivariable models: parity (0, 1-2, 3-4, >5 children), age at first birth (<20, 20-24, 25-29, >30 y), body mass index at date of diagnosis or reference year (<25, 25-29.9, >30 kg/m2), menopausal status at date of diagnosis or reference year (pre/perimenopausal, postmenopausal), age (y, continuous), age at menarche (<12, 12, 13, >4 y), center (Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Utah), education (did not graduate from high school, high school graduate or equivalent, some college, bachelors degree or higher), and number of first-degree female relatives (<1, 2, 3, >4), alcohol consumption (none, <5 g/d, 5-<10 g/d, >10 g/d), and recent hormone exposure (hormone replacement therapy use or were premenopausal) during the 2 y before the reference date (yes, no). Given that there were minimal missing data, values for individuals with missing data on these covariate variables were imputed based on group mean values and included in the analyses. Because differences in the number of female family members could contribute to observed ethnic disparities in the relationship between family history and breast cancer risk, the analysis also was adjusted for the total number of first-degree female relatives who had lived to the age of 50 y at the time of subject diagnosis or selection. These specific criteria were used to exclude those family members who are at minimal risk of developing breast cancer.

To compare prognostic characteristics between cases with and without a family history among Hispanic and NHW participants, univariate methods such as χ2 tests and t tests were initially used. Women with missing ER status were included in the univariate comparisons. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to compute the ORs and 95% CIs when assessing the ethnic-specific relationship between having a family history and ER or PR negativity while adjusting for other prognostic factors. Women missing data for the specified outcome variable (i.e., ER or PR status) were excluded. The following prognostic variables were adjusted for in the multivariable models with either ER or PR as the outcome variable: age at diagnosis (continuous), menopausal status at date of diagnosis (pre/perimenopausal, postmenopausal), center (Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Utah), stage (localized, regional, distant), grade (1, 2, 3, 4, unknown), histology (ductal, lobular, ductal and lobular, other, unknown), tumor size (<2 cm, >2 cm, unknown), frequency of mammogram screening (never, irregular, regular) and ER or PR status (yes, no). To be classified as “regular” for frequency of mammography screening, women should have (a) obtained their first mammogram before age 50 y, and (b) received an estimated frequency of screening of 1 mammogram per less than 2-year intervals. Women who did not meet both of the above criteria were classified as “irregular.” Participants who reported never having obtained a mammogram were classified as “never” having had a mammogram. For covariates with missing data, a category for unknown status was created. For age-stratified analyses, subgroups were determined according to participant characteristics at the time of diagnosis or selection. The age-stratified multivariable analysis was not adjusted for PR status due to the small sample size and the strong correlation with ER status.

Results

For both Hispanics and NHWs, women with ER negative tumors were younger than controls and more likely to be premenopausal (Table 1). Irrespective of ER status and ethnicity, cases had fewer children than controls. Among NHW women only, controls had a later age at menarche compared with cases diagnosed with either ER negative or ER positive breast cancers. Overall, women with breast cancer were more likely to report having a family history in a first-degree family member compared with control subjects among both Hispanics and NHW women. However, these differences were greater and only statistically significant for ER negative tumors among Hispanics (P < 0.01) and ER positive tumors among NHWs (P < 0.01). There was no significant difference in the proportion of cases missing ER status when comparing Hispanics and NHW (23% versus 22%, respectively; P = 0.55).

Table 1.

Breast cancer risk factors among controls and invasive breast cancer cases, as defined by estrogen receptor status, among 4-Corners Hispanic and Non-Hispanic Women

| Characteristic | Non-Hispanic White |

Hispanic |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls (n = 1,571) | ER- breast cancer (n = 185) | ER+ breast cancer (n = 736) | Controls (n = 881) | ER- breast cancer (n = 130) | ER+ breast cancer (n = 336) | |

| Family history, n (%) | ||||||

| Yes | 230 (15) | 33 (18) | 169 (23) | 116 (13) | 29 (22) | 45 (14) |

| No | 1,341 (85) | 152 (82) | 567 (77) | 765 (87) | 101 (78) | 291 (86) |

| Age in y, mean ± SD | 56.4 ± 12.2 | 52.2 ± 11.3 | 55.6 ± 10.7 | 54.5 ± 12.1 | 47.8 ±11.4 | 53.6 ± 10.8 |

| Menopause, n (%) | ||||||

| Premenopausal | 486 (31) | 78 (42) | 247 (34) | 316 (36) | 73 (56) | 124 (36) |

| Postmenopausal | 1,085 (69) | 107 (58) | 489 (66) | 565 (64) | 57 (44) | 212 (64) |

| Number of live births,* mean ± SD | 2.4 ± 1.7 | 2.0 ± 1.4 | 2.1 ± 1.5 | 3.0 ± 2.1 | 2.7 ± 2.0 | 2.5 ± 1.8 |

| Age at first birth in y,* mean ± SD | 24.1 ± 4.8 | 24.0 ± 5.4 | 24.3 ± 4.8 | 22.4 ± 4.5 | 22.4 ± 4.8 | 23.4 ± 5.4 |

| Body mass index in kg/m2, mean ± SD | 27.0 ± 6.1 | 28.0 ± 6.1 | 26.9 ± 6.0 | 29.0 ± 6.2 | 26.8 ± 4.6 | 28.7 ± 5.9 |

| Age at menarche in y, mean ± SD | 12.8 ± 1.6 | 12.4 ± 1.5 | 12.6 ± 1.6 | 12.8 ± 1.7 | 12.9 ± 1.6 | 12.7 ± 1.8 |

| Progesterone receptor positive, n (%)† | — | 13 (7) | 624 (85) | — | 18 (14) | 289 (86) |

Parous women only.

Missing progesterone receptor status (n = 7 NHW women).

When evaluating the relationship between family history of breast cancer and ER-defined breast cancer risk adjusting for other breast cancer risk factors, the observed differences between NHWs and Hispanics were still present (Table 2). Among NHW women only, having a family history of breast cancer was associated with having a marginally significant 1.4-fold increased risk (95% CI, 0.92-2.17) of ER negative breast cancer and a significant 1.9-fold increased risk (95% CI, 1.50-2.38) of having an ER positive breast cancer when compared with women without breast cancer. Among Hispanic women only, having a family history was associated with an increased risk of ER negative breast cancers (OR, 2.66; 95% CI, 1.59-4.44), but not ER positive breast cancers (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.71-1.54), when compared with women without breast cancer. The ORs were significantly different between Hispanics and NHWs for the relationship between family history and ER positive tumors (P, interaction = 0.01), but not for ER negative tumors (P, interaction = 0.15).

Table 2.

Odds ratios for breast cancer, as defined by estrogen receptor status, associated with family history of breast cancer among Hispanics and non-Hispanic Whites

| Ethnicity | Family history of breast cancer | Controls, n (%) | ER- breast cancers* |

ER+ breast cancers* |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | OR † (95% CI) | OR ‡ (95% CI) | n (%) | OR † (95% CI) | OR ‡ (95% CI) | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | No | 1,341 (85) | 152 (83) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | 567 (77) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) |

| Yes | 230 (15) | 33 (17) | 1.43 (0.95-2.16) | 1.41 (0.92-2.17) | 169 (23) | 1.80 (1.44-2.25) | 1.89 (1.50-2.38) | |

| Hispanic | No | 765 (87) | 101 (78) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | 291 (87) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) |

| Yes | 116 (13) | 29 (22) | 2.44 (1.51-3.95) | 2.66 (1.59-4.44) | 45 (13) | 1.08 (0.74-1.57) | 1.04 (0.71-1.54) | |

The P value for the interaction between ethnicity and family history was statistically significant for ER positive tumors (P = 0.01), but not ER negative tumors (P = 0.15).

OR and 95% CI from an unconditional logistic regression model adjusted for study center (Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Utah) and age (y, continuous).

OR and 95% CI from an unconditional logistic regression model adjusted for center (Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Utah), age (y, continuous), parity (0, 1-2, 3-4, >5 children), age of first birth (<20, 20-24, 25-29, >30 y), body mass index at date of diagnosis or reference year (<25, 25-29.9, >30 kg/m2), menopausal status at date of diagnosis or reference year (pre/perimenopausal, postmenopausal), age of menarche (<12, 12, 13, >14 y old), education (did not graduate from high school, high school graduate or equivalent, some college, bachelors degree or higher) and number of first-degree female relatives (<1, 2, 3, >4), alcohol consumption (none, <5 g/d, 5-<10 g/d, >10 g/d), and recent hormone exposure (hormone therapy use or were premenopausal) during the 2 y before the reference date (yes, no).

Among Hispanic and NHW women diagnosed with invasive breast cancer, we compared those with a family history with those without to evaluate the ethnic-specific association of family history with prognostic factors and tumor characteristics (Table 3). With the exception of frequency of mammography screening, there were no significant differences in any of the prognostic factors when comparing women with a family history with those without among NHW women with breast cancer. Among Hispanic women with breast cancer, cases with a family history were slightly older, more likely to be postmenopausal, more regular with mammography screening, and less likely to have an advanced stage of breast cancer at diagnosis. Consistent with the case-control comparison, Hispanic cases with a family history had a significantly higher proportion of ER negative tumors compared with those without (39.2% versus 25.8% among those with ER status available; P = 0.02). This was not observed among NHWs (16.3% versus 21.1%, respectively; P = 0.13).

Table 3.

Prognostic factors and tumor characteristics of 4-Corners invasive breast cancers according to family history of breast cancer among Hispanics and non-Hispanic Whites

| Non-Hispanic White cases |

Hispanic cases |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No family history (n = 919) | Family history (n = 256) | P* | No family history (n = 502) | Family history (n = 102) | P* | |

| Age in y, mean ± SD | 55.2 ± 11.3 | 56.2± 10.9 | 0.19 | 51.5 ± 11.5 | 55.6 ± 10.9 | <0.01 |

| Menopause, n (%) | ||||||

| Premenopausal | 325 (35) | 80 (31) | 0.22 | 228 (45) | 27 (26) | <0.01 |

| Postmenopausal | 594 (65) | 176 (69) | 274 (55) | 75 (74) | ||

| Tumor size (cm) | ||||||

| ≤2 | 606 (66) | 169 (66) | 0.33 | 278 (55) | 54 (53) | 0.87 |

| >2 | 250 (27) | 63 (25) | 190 (38) | 40 (39) | ||

| Missing | 63 (7) | 24 (9) | 34 (7) | 8 (8) | ||

| Stage | ||||||

| Local | 612 (67) | 182 (71) | 0.20 | 269 (54) | 74 (73) | <0.01 |

| Regional | 296 (32) | 69 (27) | 227 (45) | 28 (27) | ||

| Distant | 11 (1) | 5 (2) | 6 (1) | 0 (0) | ||

| Grade | ||||||

| 1 | 191 (21) | 65 (25) | 0.55 | 75 (15) | 17 (17) | 0.52 |

| 2 | 356 (39) | 99 (39) | 198 (39) | 38 (37) | ||

| 3 | 294 (32) | 72 (28) | 182 (36) | 36 (35) | ||

| 4 | 14 (2) | 4 (2) | 9 (2) | 0 (0) | ||

| Missing | 64 (7) | 16 (6) | 38 (8) | 11 (11) | ||

| Estrogen receptor | ||||||

| Positive | 567 (62) | 169 (66) | 0.31 | 291 (58) | 45 (44) | 0.03 |

| Negative | 152 (17) | 33 (13) | 101 (20) | 29 (28) | ||

| Missing | 200 (22) | 54 (21) | 110 (22) | 28 (28) | ||

| Progesterone receptor | ||||||

| Positive | 489 (53) | 149 (58) | 0.25 | 262 (52) | 45 (44) | 0.32 |

| Negative | 226 (25) | 51 (20) | 130 (26) | 30 (29) | ||

| Missing | 204 (22) | 56 (22) | 110 (22) | 27 (27) | ||

| Histology | ||||||

| Ductal | 679 (74) | 183 (71) | 0.41 | 372 (74) | 77 (75) | 0.22 |

| Lobular | 71 (8) | 30 (11) | 29 (6) | 10 (10) | ||

| Ductal/Lobular | 86 (9) | 20 (8) | 45 (9) | 9 (9) | ||

| Other | 83 (9) | 26 (10) | 56 (11) | 6 (6) | ||

| Family history of ovarian cancer | ||||||

| Yes | 17 (2) | 8 (3) | 0.19 | 11 (2) | 5 (5) | 0.12 |

| No | 876 (98) | 235 (97) | 463 (98) | 92 (95) | ||

| Mammography screening | ||||||

| Never | 115 (13) | 10 (4) | <0.01 | 97 (19) | 11 (11) | <0.01 |

| Irregular | 332 (36) | 76 (30) | 173 (35) | 25 (24) | ||

| Regular | 450 (49) | 160 (62) | 213 (42) | 63 (62) | ||

| Missing | 22 (2) | 10 (4) | 19 (4) | 3 (3) | ||

P values are inclusive of missing categories.

An assessment of the relationship between family history and ER status independent of other prognostic factors, including frequency of mammography screening, shows no association between family history and ER negativity among NHWs (OR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.48-1.26; data not shown). Given the strong correlation with PR status, we evaluated this relationship adjusting for and not adjusting for PR status. The results were similar (data not shown). In contrast, among Hispanics, breast cancer cases with a family history were 2.5 times more likely to have an ER negative tumor compared with those without a family history (95% CI, 1.27-5.00). This relationship was stronger when adjusting for PR status (OR, 3.57; 95% CI, 1.41-9.05). The interaction between family history and ethnicity as a predictor of ER status was statistically significant (P, interaction = 0.02). Multivariate analyses indicated that there were no significant associations between family history and PR status for Hispanic or NHW women (data not shown).

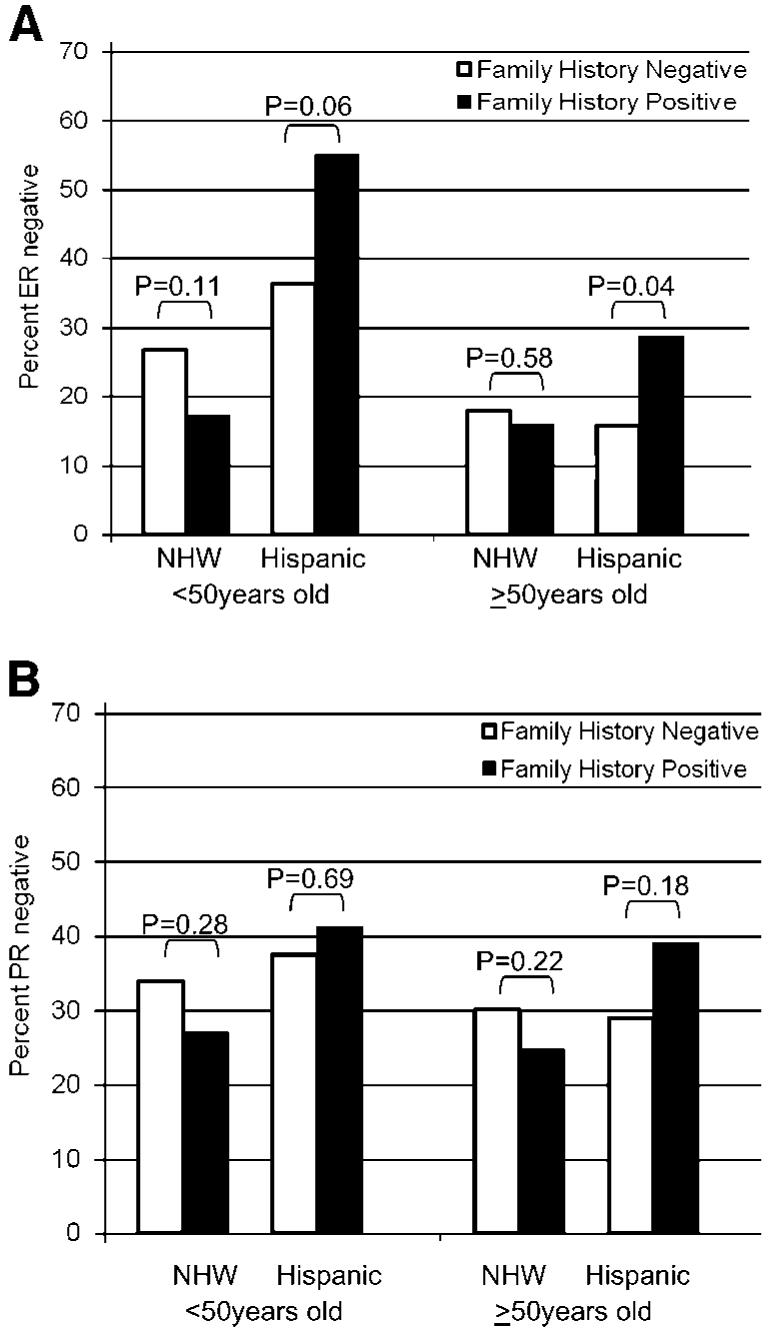

Given the typically strong relationship between family history and early-onset breast cancer, we evaluated the relationship between family history with ER and PR status stratified by age at diagnosis (<50, ≥50 years). Irrespective of age, family history was associated with having an ER negative tumor among Hispanics only (Fig. 1). No associations were observed for PR status. When adjusting for other prognostic factors, the relationship between family history and ER negativity was stronger and reached statistical significance among younger Hispanic women only (OR, 2.95; 95% CI, 1.03-8.46 for <50 years old, and OR, 2.39; 95% CI, 0.90-6.37 for >50 years old; data not shown). Based on the adjusted analysis, the interaction between family history and ethnicity as a predictor of ER status was statistically significant for younger women (P, interaction = 0.01) and marginally significant for older women (P, interaction = 0.06).

Figure 1.

Percentage of invasive breast tumors that are (A) estrogen receptor negative and (B) progesterone receptor negative according to age of diagnosis and family history among non-Hispanic White and Hispanic Women in the 4-Corners Breast Cancer Study Population.

Discussion

Among participants in the 4-Corners Breast Cancer Study, one of the largest Hispanic and NHW breast cancer case-control studies, we observed ethnic-specific differences in breast cancer risk according to ER status. Having a family history of breast cancer was associated with a significant 1.9-fold increased risk for ER positive breast cancers, and a marginally significant 1.4-fold increased risk for ER negative breast cancers among NHW women. In contrast, having a family history was associated with a significant 2.7-fold increased risk of ER negative breast cancer among Hispanic women, but no association was observed for ER positive breast cancer. When comparing tumor characteristics and prognostic factors among invasive cases only, women with a family history had a significantly higher proportion of ER negative tumors compared with women without a family history among Hispanics, but not among NHWs. Furthermore, this relationship remained significant when adjusting for other tumor characteristics and prognostic factors.

We previously observed that the relationship between family history and early-onset breast cancer varies by ethnicity. Specifically, the risk associated with having a positive family history of breast cancer in a first-degree relative was greater among NHW women compared with Hispanic women who were under the age of 50 years, yet this difference was not observed among women who were 50 years or older. In conjunction with that study, our results suggest that although family history poses a greater risk for early-onset breast cancer among NHW women, family history also seems to be associated with factors predictive of a worse prognosis (i.e., ER negative tumor status) among Hispanic women. With the exception of the rare hereditary breast cancers, having a family history of breast cancer is likely attributed to the interaction of shared genetic and environmental factors. Given the contribution of genetic factors to family history, ethnic differences in familial risk of breast cancer could at least be partially attributed to genetic differences in breast cancer predisposition among ethnic populations. Furthermore, it is likely that breast tumors attributed to certain predisposing genetic factors may have similar pathologic characteristics, such as ER status.

Among the pathologic characteristics available for this study population, we did not observe ethnic-specific associations between family history and pathologic characteristics other than ER status, such as tumor histology or PR status. Furthermore, the observed relationship between family history and ER status was independent of potential confounding factors, such as other prognostic factors (e.g., tumor size, stage, etc.) and frequency of mammography screening. It would be of interest to explore this relationship with tumor characteristics that were not available for this study population, such as HER2.

The prevalence of known hereditary breast cancer gene mutations such as BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations has not been well documented among Hispanic populations. One recent study estimated the prevalence of BRCA1 mutations to be 3.5% (95% CI, 2.1%-5.8%) in Hispanics, which was higher than other ethnic minority populations (25). Among high-risk Hispanic families, it was previously reported that 31% had BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations (26). In contrast, McKean-Cowdin et al. (27) concluded that mutations in genes other than BRCA contribute to the risk of cancer in Hispanic families because many who had a family history did not have evidence of mutation. Given the limited information, further studies exploring the role of known hereditary breast cancer gene mutations among Hispanic populations are warranted.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the relationship between family history and breast tumor characteristics among Hispanic women. Prior studies of tumor factors have found that NHW women were more likely to have smaller tumors, tumors which are estrogen receptor positive, and less lymph involvement compared with African-American and Hispanic women (4, 9, 28). More recently, it was shown that Hispanic women were more likely to have unfavorable tumor characteristics compared with NHW women despite equal access to health care services and screening practices (15). Our study provides additional support for the contribution of biological factors in promoting ethnic disparities in breast cancer outcomes.

The observed ethnic-specific relationship between family history and ER tumor subtype could suggest that Hispanic breast cancers may comprise distinct subtypes within the etiologic spectrum of breast tumors. It is well recognized that breast cancer is a complex disease, which encompasses many unidentified distinct subtypes. Recent progress in the development of high-throughput technologies has stimulated research interest in the identification of novel tumor subtypes (29). Using subtypes identified through gene expression profiling and associated with prognosis in different study populations, a recent study found that a subtype associated with poor prognosis had a higher prevalence in young African-American women compared with non-African-American women (14, 30). This is consistent with the observation that African-American women experience higher mortality rates. In summary, these findings emphasize the importance of evaluating the relationship between breast cancer risk factors and breast tumor subtypes among different ethnic populations.

Based on data obtained from the SEER cancer registries, Chu et al. previously showed that ER status has the greatest effect on delineating breast cancer patients into subgroups with unique tumor characteristics among the various ethnic/racial groups (9). Incidence rates of ER positive and ER negative breast cancers vary according to age and ethnicity (7, 9). Irrespective of ER status, breast cancer incidence rates are higher among NHW compared with Hispanics (7, 9). When comparing these populations, however, the magnitude of the difference in breast cancer incidence rates seems to be dependent on ER status. In other words, NHW women have ∼2-fold higher incidence rates for ER positive breast cancers compared with Hispanics, irrespective of age at diagnosis. However, the magnitude of the difference in incidence rates for ER negative tumors was not as large, particularly for early-onset breast cancers. Specifically, among women under the age of 50 years, the incidence rate for ER negative breast cancers was only 1.4 times higher for NHWs compared with Hispanics. In relative terms, these data may reflect an overrepresentation of ER negative tumors among younger Hispanic women, which is consistent with the observation that the relationship between family history and ER negativity is stronger among younger women. Alternatively, it may reflect an unexplained greater excess of ER positive tumors among older NHW women.

The strengths of this study include the ability to account for a number of risk factors and prognostic factors, a large sample size, and a considerable representation of Hispanic women. There are also limitations with respect to this study. Because this is a case-control study design, there is potential for survival bias attributed to the prognostic value of ER status. Thus, this study’s population could have an overrepresentation of women with ER positive tumors. When compared with previously published results using SEER cancer registries, there was a slight overrepresentation of ER positive tumors among the 4-Corners Breast Cancer Study population (7). Among women who were under 50 years of age, a slight overrepresentation of ER positive tumors was observed among NHW women (4-Corners, 75% versus SEER, 67%), but not among Hispanics (61% versus 60%, respectively; ref. 7). Among women 50 years and older, there was a slight overrepresentation of ER positive tumors among Hispanic women (4-Corners, 82% versus SEER, 76%), but not NHW women (82% versus 81%, respectively; ref. 7). It is unlikely that these small differences account for the relationship observed in this study. Furthermore, the overrepresentation of favorable ER positive tumors among women with a family history is more likely to attenuate the observed relationship with ER negativity. Another limitation is the large proportion of missing data on tumor characteristics for the 4-Corners Study, which was obtained from the cancer registries. Missing data compromised power, but it did not seem to be differential based on ethnicity (missing ER status, 22% for NHW and 23% for Hispanics) and is unlikely to be associated with family history.

Other limitations include the inability to consider second-degree family relatives and the reliability of family history based on self-report. It has recently been shown that second-degree family history does not have a substantial effect when estimating breast cancer risk (31). A previous study assessed the validity of reporting family history in population-based registries of breast, ovarian, and colorectal cancer probands and found a high reliability of reporting that did not vary by race or ethnicity (32). Furthermore, we would not expect differences of reporting family history to be dependent on ER status. Nevertheless, given these limitations, further studies are warranted to confirm these findings.

In summary, our findings indicate an ethnic-specific relationship between family history of breast cancer and ER-defined breast cancer among Hispanic and NHW women. Among Hispanics, having a family history was associated with increased risk of having an ER negative breast cancer. In addition, Hispanics breast cancer cases with a family history were more likely to be ER negative compared with those without a family history, particularly among younger women. These differences were not observed among NHW women. Our study provides additional support for the role of biological factors in contributing to ethnic disparities in breast cancer outcomes. Given the contribution of genetic factors to family history, these results may reflect ethnic-specific predisposing genetic factors that promote the development of specific breast tumor subtypes. These findings emphasize the importance of evaluating the relationship between breast cancer risk factors and breast tumor subtypes among different ethnic populations.

Acknowledgments

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked advertisement in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Grant support: The 4-Corners Study was funded by the National Cancer Institute, NIH, Department of Health and Human Services (CA078682, CA078762, CA078552, and CA078802). This work was funded by an American Cancer Society Institutional Research Grant, University of Colorado Cancer Center Seed Money/Fellowship grant (L. Hines).

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Li CI, Malone KE, Daling JR. Differences in breast cancer hormone receptor status and histology by race and ethnicity among women 50 years of age and older. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:601–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li CI, Malone KE, Daling JR. Differences in breast cancer stage, treatment, and survival by race and ethnicity. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:49–56. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joslyn SA. Hormone receptors in breast cancer: racial differences in distribution and survival. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2002;73:45–59. doi: 10.1023/a:1015220420400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elledge RM, Clark GM, Chamness GC, Osborne CK. Tumor biologic factors and breast cancer prognosis among white, Hispanic, and black women in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:705–12. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.9.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clegg LX, Li FP, Hankey BF, Chu K, Edwards BK. Cancer survival among US whites and minorities: a SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) Program population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1985–93. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.17.1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shavers VL, Harlan LC, Stevens JL. Racial/ethnic variation in clinical presentation, treatment, and survival among breast cancer patients under age 35. Cancer. 2003;97:134–47. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chu KC, Anderson WF. Rates for breast cancer characteristics by estrogen and progesterone receptor status in the major racial/ethnic groups. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2002;74:199–211. doi: 10.1023/a:1016361932220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frost F, Tollestrup K, Hunt WC, Gilliland F, Key CR, Urbina CE. Breast cancer survival among New Mexico Hispanic, American Indian, and non-Hispanic white women (1973-1992) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1996;5:861–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chu KC, Anderson WF, Fritz A, Ries LA, Brawley OW. Frequency distributions of breast cancer characteristics classified by estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor status for eight racial/ethnic groups. Cancer. 2001;92:37–45. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010701)92:1<37::aid-cncr1289>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martinez ME, Nielson CM, Nagle R, Lopez AM, Kim C, Thompson P. Breast cancer among Hispanic and non-Hispanic White women in Arizona. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007;18:130–45. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2007.0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aldridge ML, Daniels JL, Jukic AM. Mammograms and healthcare access among US Hispanic and non-Hispanic women 40 years and older. Fam Community Health. 2006;29:80–8. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200604000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coughlin SS, Uhler RJ, Bobo JK, Caplan L. Breast cancer screening practices among women in the United States, 2000. Cancer Causes Control. 2004;15:159–70. doi: 10.1023/B:CACO.0000019496.30145.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Longman AJ, Saint-Germain MA, Modiano M. Use of breast cancer screening by older Hispanic women. Public Health Nurs. 1992;9:118–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.1992.tb00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carey LA, Perou CM, Livasy CA, et al. Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study. Jama. 2006;295:2492–502. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.21.2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watlington AT, Byers T, Mouchawar J, Sauaia A, Ellis J. Does having insurance affect differences in clinical presentation between Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women with breast cancer? Cancer. 2007;109:2093–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Althuis MD, Fergenbaum JH, Garcia-Closas M, Brinton LA, Madigan MP, Sherman ME. Etiology of hormone receptor-defined breast cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:1558–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colditz GA, Rosner BA, Chen WY, Holmes MD, Hankinson SE. Risk factors for breast cancer according to estrogen and progesterone receptor status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:218–28. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer Familial breast cancer: collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 52 epidemiological studies including 58,209 women with breast cancer and 101,986 women without the disease. Lancet. 2001;358:1389–99. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06524-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oldenburg RA, Meijers-Heijboer H, Cornelisse CJ, Devilee P. Genetic susceptibility for breast cancer: how many more genes to be found? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2007;63:125–49. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slattery ML, Sweeney C, Edwards S, et al. Body size, weight change, fat distribution and breast cancer risk in Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;102:85–101. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9292-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Howard CA, Samet JM, Buechley RW, Schrag SD, Key CR. Survey research in New Mexico Hispanics: some methodological issues. Am J Epidemiol. 1983;117:27–34. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rogers A, Murtaugh MA, Edwards S, Slattery ML. Contacting controls: are we working harder for similar response rates, and does it make a difference? Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:85–90. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sweeney C, Edwards SL, Baumgartner KB, et al. Recruiting Hispanic women for a population-based study: validity of surname search and characteristics of nonparticipants. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166:1210–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Risendal B, Hines LM, Sweeney C, et al. Family history and age at onset of breast cancer in Hispanic and Non-Hispanic White women. Cancer Causes Control; In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.John EM, Miron A, Gong G, et al. Prevalence of pathogenic BRCA1 mutation carriers in 5 US racial/ethnic groups. Jama. 2007;298:2869–76. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.24.2869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weitzel JN, Lagos V, Blazer KR, et al. Prevalence of BRCA mutations and founder effect in high-risk Hispanic families. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:1666–71. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKean-Cowdin R, Spencer Feigelson H, Xia LY, et al. BRCA1 variants in a family study of African-American and Latina women. Hum Genet. 2005;116:497–506. doi: 10.1007/s00439-004-1240-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gann PH, Colilla SA, Gapstur SM, Winchester DJ, Winchester DP. Factors associated with axillary lymph node metastasis from breast carcinoma: descriptive and predictive analyses. Cancer. 1999;86:1511–9. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19991015)86:8<1511::aid-cncr18>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406:747–52. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sorlie T, Tibshirani R, Parker J, et al. Repeated observation of breast tumor subtypes in independent gene expression data sets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:8418–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0932692100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Welsh ML, Buist DS, Aiello Bowles EJ, Anderson ML, Elmore JG, Li CI. Population-based estimates of the relation between breast cancer risk, tumor subtype, and family history. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0026-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ziogas A, Anton-Culver H. Validation of family history data in cancer family registries. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24:190–8. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00593-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]