Abstract

Although human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is generally not regarded to be an oncogenic virus, HCMV infection has been implicated in malignant diseases from different cancer entities. On the basis of our experimental findings, we developed the concept of “oncomodulation” to better explain the role of HCMV in cancer. Oncomodulation means that HCMV infects tumor cells and increases their malignancy. By this concept, HCMV was proposed to be a therapeutic target in a fraction of cancer patients. However, the clinical relevance of HCMV-induced oncomodulation remains to be clarified. One central question that has to be definitively answered is if HCMV establishes persistent virus replication in tumor cells or not. In our eyes, recent clinical findings from different groups in glioblastoma patients and especially the detection of a correlation between the numbers of HCMV-infected glioblastoma cells and tumor stage (malignancy) strongly increase the evidence that HCMV may exert oncomodulatory effects. Here, we summarize the currently available knowledge about the molecular mechanisms that may contribute to oncomodulation by HCMV as well as the clinical findings that suggest that a fraction of tumors from different entities is indeed infected with HCMV.

Introduction

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is a ubiquitous herpes virus that leads to a life-long persistence. The frequency of infection ranges from 50% to 100% in the general adult population. Human cytomegalovirus causes severe and often fatal disease in immunocompromised individuals including recipients of organ transplants and AIDS patients. It routinely reactivates in healthy virus carriers, but this is usually controlled by the host immune response [1–3]. Monocytes may be an important reservoir for latent HCMV; however, the primary reservoir may be a more primitive cell from the myeloid lineage. Reactivation may result from cellular differentiation or inflammation [1–3].

The (possible) relationship between HCMV infection and cancer has been investigated for decades (for review see, e.g., [1]). Detection of viral DNA, mRNA, and/or antigens in tumor tissues as well as seroepidemiologic evidence suggested a role of HCMV infection in the etiology of several human malignancies.

In the 1970s, the group of Fred Rapp reported HCMV to transform normal human embryonal cells in vitro [4,5]. Although the transformed cell lines exhibited enhanced tumorigenicity in nude mice, the expression of HCMV-specific antigens in the transformed and tumor-derived lines decreased with increasing passage [6]. In later studies using normal rodent cells, HCMV (infectious virus or virus DNA) was shown to induce mutations in genes that are critical for malignant transformation [7–10]. However, viral DNA was not detected in most transformants. These findings led to the speculation that HCMV contributes to oncogenesis by “hit-and-run” mechanism [7–10]. However, this scenario is difficult to prove because it supposes that virus nucleic acids are not retained in transformed cells. In fact, up to now, there is no conclusive evidence for the transformation of normal cells after HCMV infection in humans, and the mechanism by which HCMV might contribute to oncogenesis remains obscure. Today, it is generally accepted that infection of normal permissive cells with HCMV does not result in malignant transformation (cells actively expressing virus no longer divide and eventually die), so that the virus is not considered to be oncogenic.

Twelve years ago, we proposed the concept of oncomodulation in which HCMV may favor tumor progression without being an oncogenic virus to explain the frequent presence of HCMV in tumor tissues [11]. Oncomodulation means that HCMV may infect tumor cells and modulate their malignant properties, in a fashion not involving direct transformation. We postulated that tumor cells provide a genetic environment, characterized by disturbances in intracellular signaling pathways, transcription factors, and tumor suppressor proteins, that enables HCMV to exert its oncomodulatory potential, although it cannot be manifested in normal cells. To study these effects, we established persistently HCMV-infected cancer cell lines (see, e.g., [11–14]). Studies in these cell lines demonstrated that long-term persistent HCMV infection is necessary to fully express oncomodulatory effects. Subcutaneous injection of persistently HCMV-infected neuroblastoma cells resulted in increased malignant behavior as indicated by enhanced tumor growth and metastasis formation compared to noninfected cells [11]. Moreover, we identified HCMV as a potential therapeutic target for patients with HCMV-infected tumors [11,13,14].

Human cytomegalovirus—induced oncomodulation may result from the activity of virus regulatory proteins and noncoding RNA, which influence properties of tumor cells including cell proliferation, survival, invasion, production of angiogenic factors, and immunogenicity. As a result, HCMV infection may lead to a shift to a more malignant phenotype of tumor cells and tumor progression [1,14]. The clinical relevance of these experimental findings remains a matter of debate. We will first briefly summarize the molecular mechanisms that may underlie HCMV-induced oncomodulation before we discuss the current evidence concerning its clinical relevance.

Molecular Mechanisms of HCMV-Induced Oncomodulation

Influence of HCMV on the Cell Cycle of Cancer Cells

In normal permissive cells, HCMV-encoded regulatory proteins induce cell cycle arrest and prevent cellular DNA replication but maintain an active state that enables replication of viral DNA [15,16]. In HCMV-infected cells, the expression of the cyclins D1 and A is inhibited, although hallmarks of S-phase, including pRB hyperphosphorylation, cyclin E and cyclin A kinase activation, and expression of many S-phase genes are present.

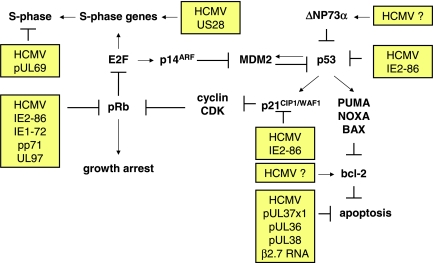

Several HCMV regulatory proteins such as the 72-kDa immediate early-1 (IE1-72), 86-kDa IE2-86, and the tegument protein pp71 were shown to interact and inactivate proteins of the Rb family (pRb, p107, and p130) promoting entry into S phase of the cell cycle. Moreover, the UL97 protein was shown to exert cyclin-dependent kinase activity resulting in phosphorylation and inactivation of pRb [17]. Conversely, HCMV IE2-86 may induce cell cycle arrest by activating an ataxia telangiectasia mutated gene—dependent phosphorylation of p53 at Ser15. These events result in p53 accumulation and activation, leading to a p53- and p21-dependent inhibition of cell cycle progression [18]. Other virus regulatory proteins, for example, the pUL69, contribute to HCMV-induced cell cycle arrest [15].

In tumor cells, cell cycle is commonly deregulated [19,20]. In cells with disrupted cell cycle control mechanisms (such as tumor cells), the function of virus regulatory proteins may depend on the internal context of tumor cells [14] (Figure 1). In normal fibroblasts expressing wild-type p53, HCMV IE1-72 protein cannot drive cells out of quiescence, whereas IE1-72 can induce S phase and delay cell cycle exit in p53-deficient cells. Human cytomegalovirus IE2-86 protein induces a G1/S block in human cells with wild-type pRb, but not in the human Rb-deficient osteosarcoma cell line Saos-2. In T89G glioblastoma cells with disrupted p53 signaling, persistent HCMV infection did not induce cell cycle arrest and virus antigen-positive cells continued to divide [21]. In experiments using a panel of human glioblastoma cell lines, a stable expression of IE1-72 was shown to differentially affect cell growth, resulting either in cell proliferation or in arrest. In U87 and U118 glioblastoma cells, IE1-72—induced proliferation was paralleled by reduction in steady state expression levels of pRb and p53 family (including p53, p63, or p73) members. In contrast, IE1-72 expression in LN229 and U251 glioblastoma cells was associated with increased expression of p53 family proteins, accompanied by growth arrest [22]. The HCMV protein US28 promoted cell cycle progression and cyclin D1 expression in cells with a tumorigenic phenotype, whereas it induced apoptosis in nontumorigenic cells [23].

Figure 1.

Major effects of HCMV on regulators of tumor cell cycle and/or apoptosis. CDK, cyclin-dependent kinase; E2F, E2F transcription factor; MDM2, mouse double minute 2.

It has also been shown that persistent HCMV infection of tumor cells may lead to a selection of novel virus variants characterized by changes in coding sequences for virus regulatory proteins that have lost their ability to induce cell cycle arrest. Human cytomegalovirus persistent infection of tumor cells including glioblastoma and osteosarcoma results in the development of mutated virus variants, which grow slowly and yield lower amounts of progeny virus compared to wild-type virus strains originally used for infection [24,25]. These HCMV variants were found to have DNA deletions in their genome and synthesized IE protein different in size from those of the wildtype virus strain. Moreover, stable expression of HCMV IE2-86 protein in retrovirus-transduced fibroblasts did not abrogate the G1 checkpoint owing to a mutation within a critical carboxyl-terminal domain of IE2-86 protein, thus making it unable to halt cell cycle progression [26]. Infection of fibroblasts with an HCMV strain containing a deletion in the UL69 gene failed to induce a block in the G1/S phase of the cell cycle [27]. These findings demonstrate that the effects of HCMV on cell cycle and cell proliferation may depend both on the context of the internal cellular environment and on the properties of virus regulatory proteins.

Influence of HCMV on Cancer Cell Apoptosis

Resistance to apoptosis is a common feature of cancer cells and represents a relevant chemoresistance mechanism [19,20,28–30]. The first study on HCMV infection and apoptosis revealed that HCMV protects fibroblasts from apoptosis induced by adenovirus E1A protein [31]. Moreover, the HCMV IE1-72 and IE2-86 proteins inhibited apoptosis induced by the adenovirus E1A and TNF-α but not by irradiation with UV light in cervix carcinoma HeLa cells [31]. The authors speculated that HCMV exerts its antiapoptotic effects through IE proteins by both p53-independent and p53-dependent mechanisms. In fact, other investigators revealed that, in some cells, HCMV IE2-86 binds to p53, inhibits its transactivating function, and protects from p53-mediated apoptosis under conditions that would otherwise induce the pathway [32–36] (Figure 1). IE2-86 inhibited doxorubicin-induced apoptosis in smooth muscle cells, indicating that IE2-86 can suppress p53-mediated apoptosis after DNA damage [35]. Furthermore, ts13 cells with a temperature-sensitive mutation in TAFII250 do not undergo p53-dependent apoptosis when IE2-86 is expressed and the cells are grown at the nonpermissive temperature [36].

Direct antiapoptotic activity of HCMV proteins was ascribed mainly to some distinct transcripts encoded by the HCMV UL36-UL38 genes [37,38]. The product of UL36, a viral inhibitor of caspase activation, binds to the prodomain of caspase-8, thus inhibiting Fas-mediated apoptosis [39,40]. The UL37 gene product, UL37 exon 1 (UL37x1), a viral mitochondrial inhibitor of apoptosis, inhibits the recruitment of the proapoptotic endogenous Bcl-2 family member Bax and Bak to mitochondria, resulting in their functional neutralization [41,42]. Notably, cervix carcinoma HeLa cells expressing the viral mitochondrial inhibitor of apoptosis were resistant to apoptosis triggered by doxorubicin. The HCMV UL38 gene encodes a protein that protects infected cells from apoptosis induced by a mutant adenovirus lacking the antiapoptotic E1B-19K protein or by thapsigargin, which disrupts calcium homeostasis in the endoplasmic reticulum [43]. In cells infected with wild type virus, pUL38 was shown to interact with tuberous sclerosis tumor suppressor protein complex resulting in a failure to regulate the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 [44]. Viral 2.7-kb noncoding RNA (β2.7) inhibited apoptosis in infected U373 glioma cells subjected to mitochondrial stress by stabilizing the mitochondrial respiratory chain complex I [45].

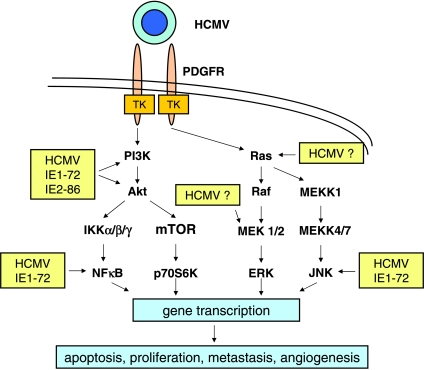

Human cytomegalovirus infection was shown to protect tumor cells from apoptosis by the induction of cellular proteins, including AKT, Bcl-2, and ΔNp73α [13,14]. Human cytomegalovirus binding to its cellular receptors such as integrins initiates activation of AKT through the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway. Moreover, stable expression of the IE1-72 protein was sufficient to sustain increased AKT activity in glioblastoma cells independently of virus receptor signaling [22]. Recently, HCMV glycoprotein B was shown to bind to the platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) and to initiate activation of AKT through the PI3K pathway in different cell types including U87 glioma cells [46] (Figure 2). Furthermore, HCMV activated AKT by selective phosphorylation of the upstream nonreceptor cellular kinase focal adhesion kinase (FAK) at Tyr397, in glioblastoma and prostate carcinoma cell lines [47,48]. Activation of other signaling pathways including those mediated by mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) kinase (MEK) 1/2 or the c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) may be induced through viral regulatory proteins and/or binding of HCMV glycoproteins to PDGFR or virus coreceptors including integrins and Toll-like receptor 2 [1,46]. These complex events may result in gene transcription, which alters apoptotic responses and other malignant properties of tumor cells (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Major signaling pathways activated by HCMV binding to the PDGFR and/or by HCMV immediate early (IE) proteins that may contribute to oncomodulation by HCMV. Akt, murine thymoma viral (v-akt) oncogene homolog-1 (protein kinase B); ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; IKK, inhibitor of NF-κB kinase; JNK, c-jun N-terminal kinase;MEK,MAPK/ERK kinase;MEKK,MEK kinase;mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; NF-κB, nuclear factor κB; p70S6K, 70-kDa ribosomal S6 kinase; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase.

Increased expression of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 and decreased sensitivity to chemotherapeutic agents were reported in HCMV-infected neuroblastoma and colon carcinoma cell lines [13,49]. Other observations showed that HCMV infection induced accumulation of the ΔNp73α isoform in glioblastoma and neuroblastoma cell lines [50,51]. Human cytomegalovirus-induced ΔNp73α exerted a dominant-negative effect on p73α- and p53-dependent apoptosis in both p53-negative and p53 wild type tumor cells [50] (Figure 1). In persistently infected neuroblastoma cells, HCMV decreased the expression of p73 with a concomitant increase in N-myc expression, suggesting that HCMV could also enable neuroblastoma cells to escape the apoptotic properties of p73 through N-myc-dependent pathway [50].

Influence of HCMV on Cancer Cell Invasion, Migration, and Adhesion to the Endothelium

Cancer cell invasion, migration, and adhesion to the endothelium play important roles during formation of metastases [52–54]. Neuroblastoma cells persistently infected with HCMV expressed increased motility and adhesion to human endothelial cells [1]. The increased adhesion to endothelium was mediated by activation of β1α5 integrin on a surface of infected tumor cells, which led to a focal disruption of endothelial cell integrity, thus facilitating tumor cell transmigration. Moreover, HCMV downregulated neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM; CD56) receptors in persistently infected neuroblastoma cells contributing to augmented tumor cell adhesion and transendothelial penetration [51]. The effects of HCMV on NCAM also account for decreased adhesion of cancer cells to each other, which is presumably one of the first steps in metastasis. The inhibitory effects of HCMV on NCAM expression may stem from the suppression of p73 expression in infected cells, resulting in decreased transactivation of the NCAM promoter by p73.

In human prostate cancer PC-3 cells, HCMV infection upregulated tumor cell adhesion to the endothelium and to extracellular matrix proteins. This process was accompanied by the enhancement of β1-integrin surface expression, elevated levels of integrin-linked kinase, and phosphorylation of FAK at Tyr397 [47]. In human malignant glioma cells, HCMV infection also increased extracellular matrix—dependent migration and invasion in dependence on FAK phosphorylation at Tyr397 [48]. These effects were not observed in normal astroglial cells, suggesting that HCMV can selectively augment glioma invasiveness.

US28 protein, a G protein—coupled chemokine receptor encoded by HCMV, induces arterial smooth muscle cell migration by a ligand-dependent process [55]. It has been shown that US28 signals through the non—receptor protein tyrosine kinases Src and FAK and that this activity is necessary for US28-mediated smooth muscle cell migration [56]. It is of interest to show whether the US28 pathway may contribute to FAK activation and stimulation of cell invasion observed in HCMV-infected tumor cells.

Investigation of gene expression in several persistently HCMV-infected neuroblastoma cell lines by gene microarray revealed up-regulation of genes that are involved in cancer cell invasion [57].

Influence of HCMV on Angiogenesis

Recruitment of tumor vessels is an integral part of cancer initiation and progression [19,58,59]. US28 protein, a G protein—coupled chemokine receptor encoded by HCMV, induced a proangiogenic and transformed phenotype in mouse fibroblast NIH-3T3 cells through up-regulation of vascular endothelial factor [23]. US28-expressing cells were tumorigenic in nude mice. Expression of a G protein—uncoupled constitutively inactive mutant of US28 delayed and attenuated tumor formation, indicating a role of constitutive receptor activity in the onset of tumor development. Importantly, US28 was also shown to be involved in HCMV-induced angiogenesis in glioblastoma cells infected with a clinical HCMV strain through the induction of vascular endothelial factor production. Moreover, expression of interleukin 8 (IL-8), another well-recognized promoter of tumor angiogenesis, was stimulated by HCMV infection in leukemia and glioma cells [60,61]. Human cytomegalovirus-induced IL-8 expression may be caused by the ability of the HCMV IE1-72 protein to transactivate the IL-8 promoter through the cellular transcription factors NF-κB and AP-1 [61]. In addition, HCMV infection of glioma cells suppressed the expression of angiogenesis inhibitors, such as thrombospondins 1 and 2, through the activity of IE proteins without the involvement of p53 [62,63].

Human cytomegalovirus infection of endothelial cells resulted in proangiogenic effects mediated through virus binding to and signaling through integrin β1, integrin β3, and epidermal growth factor receptor [64]. Secretome analysis of HCMV-infected cells revealed enhanced levels of proangiogenic molecules as well as increased proangiogenic activity of cell-free supernatants [65]. By this mechanism, tumor cells themselves as well as nontransformed stroma cells (e.g., fibroblasts or endothelial cells) may contribute to cancer progression.

Influence of HCMV on Cancer Cell Immunogenicity

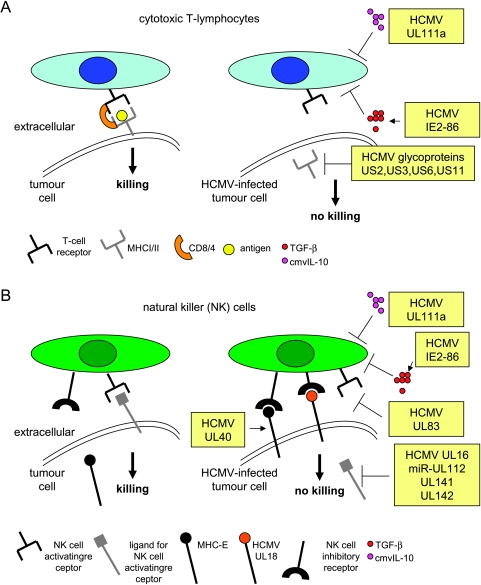

The ability to evade from recognition by the immune system is essential for cancer cells [66,67]. The HCMV proteins US2, US3, US6, and US11 decrease cell surface expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I or class II proteins, which may help infected cells to avoid adaptive immune response [68,69] (Figure 3A). The HCMV-encoded protein UL16 provides protection against detection by immune cells through preventing the MHC class I—related chain B, UL16 binding proteins 1 and 2 from reaching the cell surface, whereas HCMV microRNA (miR-UL112) prevents expression of MHC class I-related chain B in infected cells [68,70,71]. MHC class I—related chain B and UL16 binding proteins are cellular ligands for the activating receptor NKG2D, which is expressed on some natural killer (NK) cells, γ/σ T cells, and CD8+ cells. Other HCMV-encoded proteins such as MHC class I homolog UL18 and UL40 may inhibit NK responses against infected cells by triggering NK inhibitory CD94/NKG2A receptor [71] (Figure 3B). The potential contribution of such oncomodulatory mechanisms to tumor progression was shown in a murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV) model. Expression of the MCMV-encoded class I homolog m144 protected lymphoma cells from NK cell lysis resulting in increased tumor growth and decreased survival in a syngeneic mouse model [72].

Figure 3.

Immune escape mechanisms mediated by HCMV in tumor cells. (A) Influence of HCMV gene products cytotoxic T-cell lysis in tumor cells, (B) influence of HCMV gene products (and microRNA) on natural killer cell lysis in tumor cells. MHC, major histocompatibility complex; TGF-β, transforming growth factor β.

Human cytomegalovirus-infected tumor cells may avoid immune responses also by production of immunosuppressive cytokines. The HCMV-encoded viral IL-10 homolog (UL111a; cmvIL-10) exerts potent immunosuppressive properties similar to those of IL-10 produced by human cells [73–75]. During latent infection, the UL111a region transcript undergoes alternative splicing, which results in the expression of latency-associated cmvIL-10. The latency-associated cmvIL-10 retains some, but not all, of the immunosuppressive functions of cmvIL-10 and its expression may enable HCMV to avoid immune recognition and clearance during latency [75]. This may be of relevance for tumor cells with limited permissiveness for HCMV. Moreover, HCMV stimulated the production of the cellular immune suppressive cytokine transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) in different tumor cell types including glioblastoma, leukemia, and osteosarcoma cells [76,77]. Interestingly, TGF-β1 is regarded to be the most prominent glioblastoma-associated immunosuppressant [78]. Moreover, TGF-β1 itself had already been shown to stimulate HCMV replication in cultured cells [79]. A comparative study of the influence of HCMV infection and IE protein expression on TGF-β1 promoter function in permissive cells pointed to a possible cooperative role between IE proteins and protein(s) expressed during the early phase of viral infection [76]. In the human glioma cell line U373, the HCMV IE2-86 protein regulates transcription of the TGF-β1 gene by its ability to interact with the Egr-1 DNA-binding protein [80]. In addition HCMV was shown to induce integrin αvβ6 expression in endothelial cells of different tissues in patients with HCMV infection. The expression of integrin αvβ6 in HCMV-infected cells promoted activation of TGF-β1 from its secreted biologically inactive form [81]. Therefore, HCMV may influence individual infected cells, surrounding tissues, and/or immune reactions through TGF-β1 production and/or activation. This may promote virus replication and interfere with host immune responses against tumor cells.

Influence of HCMV on Chromosome Stability

Human cytomegalovirus infection has been demonstrated to induce chromosome damage [82], and genetic instability is considered to be major driver of cancer progression [83,84]. In 1972, chromosome damage induced by HCMV infection in human cells was reported for the first time [85]. Human cytomegalovirus infection in combination with cytotoxic agents synergistically increased genotoxic effects [86,87]. Most notably, HCMV was shown to induce specific chromosome 1 strand breaks at positions 1q42 and 1q21 in a replication-independent manner [88]. The possible targets residing near 1q42 include the ADPRT locus involved in DNA repair and replication [89] whose deletion has been connected to the development of glioblastoma [90]. A breast cancer tumor suppressor gene was proposed to be located at 1q21-31 [91], therefore representing a potential target of 1q21 strand breaks.

Human cytomegalovirus IE1-72 and IE2-86 gene products can cooperate with the adenovirus E1A protein to transform primary baby rat kidney (BRK) cells [9]. The finding that many of the transformed BRK cell lines contained mutated p53 alleles suggest that mutation of p53 might be one of the mechanisms by which IE proteins contribute to transformation. Because HCMV proteins and DNA were not present in cell lines derived from the transformed BRK foci, it has been suggested that HCMV could contribute to oncogenesis by “hit-and-run” mechanism [9]. In addition, three different cell lines transformed by HCMV were shown to harbor an activating mutation in both alleles in H-Ras [8]. However, in both cases, it is unclear whether the mutations in H-Ras or p53 are a direct result of the mutagenic activity of HCMV gene products. The mutations could arise as the transformants are selected for growth in culture.

Clinical Findings

Although HCMV infection of tumor cells was initially reported 30 years ago in patients with carcinomas such as prostate or colon cancer, later pathologic investigations provided conflicting results [14]. A renewed interest in the role of HCMV in cancer diseases was promoted by recent studies using highly sensitive techniques for virus detection which indicated the presence of genome and antigens, of HCMV in tumor cells (but not in adjacent normal tissue) of more than 90% of patients with certain malignancies, such as colon cancer, malignant glioma, prostate carcinoma, and breast cancer [3,49,92–96]. These pathologic observations demonstrated that HCMV causes low-grade infections in tumor cells probably sustained by persistent virus replication. To further understand whether HCMV infection in tumors is of clinical relevance, patients with malignant glioblastoma were grouped according to the level of HCMV-infected tumor cells. Remarkably, patients with low levels lived almost twice as long as patients with high levels suggesting that HCMV infection of tumor cells alters the disease course in this patient group [3]. Moreover, detection of HCMV in different histologic types of gliomas revealed that HCMV-positive cells in glioblastoma multiforme were 79% compared to 48% in lower grade tumors [96]. Recent clinical studies also demonstrated the presence of HCMV DNA in the peripheral blood of a high percentage of glioblastoma patients (80%) but not in the blood of healthy control individuals [94]. These results suggest either a systemic reactivation of HCMV within patients with glioblastoma (which may be relevant for virus transport from periphery into the tumor tissues) or shedding of viral DNA after reactivation of latent HCMV in tumor cells into the periphery. Although HCMV viremia exerts subclinical character in glioblastoma patients, it may be relevant for the transport of HCMV into tumor tissues by immune cells such as monocytes/macrophages. A secondary reactivation of virus may be caused by cancer-related and/or treatment-related immunosuppression. In fact, a pilot clinical study showed that the incidence of HCMV reactivation in patients receiving conventional chemotherapy (without major immunosuppressive agents) may be high without obvious HCMV disease [94]. It should also be noted that HCMV reactivation seems to be dependent on differentiation of myeloid lineage and inflammation [2,3]. In patients with different inflammatory disorders, HCMV reactivation was evident in inflamed tissues but not in non-inflamed tissue specimens from the same patient or healthy controls [3]. Therefore, inflammatory environment present in most solid tumors could contribute to local HCMV reactivation. Conversely, HCMV also exerts proinflammatory potential mainly owing to the production of numerous inflammatory mediators from infected cells [14]. Thus, HCMV reactivation in cancer tissues may enhance tumor inflammation and accelerate a malignant process.

Conclusions

Many clinical and experimental findings suggest a contribution of HCMV to malignancy and chemoresistance of infected tumor cells from different entities. However, oncomodulation needs to be further defined in a systematic manner to increase the understanding of the phenomenon and to better translate the experimental results in more effective anticancer therapies. First, standardization of highly sensitive techniques is necessary to detect low-grade HCMV infection of tumor tissues to reasonably compare pathologic studies from different groups. Moreover, the clinical relevance of experimentally defined oncomodulatory mechanisms induced by HCMV regulatory proteins and noncoding RNA needs to be examined. This includes the investigation of the HCMV oncomodulatory activity in the context of the internal cellular environment in tumor tissues and genetic and functional studies of HCMV strains isolated from patients' tumor samples. Hereby, it is important to study HCMV-induced oncomodulation not only in infected tumor cells but also in stroma cells, because HCMV-induced changes in the tumor microenvironment may also contribute to oncomodulation. Another central aim is to develop therapeutic strategies to suppress HCMV replication or to target viral regulatory proteins or noncoding RNA because persistent virus replication is supposed to be essential for oncomodulation. Clinical trials to evaluate the efficacy of antiviral treatment or HCMV-targeted immunotherapy in patients with malignant glioblastoma have just been started [3,94]. Most recently, an HCMV-specific CD8+ T-cell response was induced in a glioblastoma patient after therapeutic vaccination with dendritic cells pulsed with autologous tumor lysate [95]. This finding supports that HCMV may be a potential immunotherapeutic target in HCMV-infected tumors and should therefore be a further impulse to strengthen our effor.

References

- 1.Cinatl J, Scholz M, Kotchetkov R, Vogel JU, Doerr HW. Molecular mechanisms of the modulatory effects of HCMV infection in tumor cell biology. Trends Mol Med. 2004;10:19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sinclair J. Human cytomegalovirus: latency and reactivation in the myeloid lineage. J Clin Virol. 2008;41:180–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Söderberg-Nauclér C. HCMV microinfections in inflammatory diseases and cancer. J Clin Virol. 2008;41:218–223. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geder KM, Lausch R, O'Neill F, Rapp F. Oncogenic transformation of human embryo lung cells by human cytomegalovirus. Science. 1976;192:1134–1137. doi: 10.1126/science.179143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geder L, Kreider J, Rapp F. Human cells transformed in vitro by human cytomegalovirus: tumorigenicity in athymic nude mice. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1977;58:1003–1009. doi: 10.1093/jnci/58.4.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geder L, Laychock AM, Gorodecki J, Rapp F. Alterations in biological properties of different lines of cytomegalorivus-transformed human embryo lung cells following in vitro cultivation. IARC Sci Publ. 1978;24:591–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson JA, Fleckenstein B, Jahn G, Galloway DA, McDougall JK. Structure of the transforming region of human cytomegalovirus AD169. J Virol. 1984;49:109–115. doi: 10.1128/jvi.49.1.109-115.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boldogh I, Huang ES, Rady P, Arany I, Tyring S, Albrecht T. Alteration in the coding potential and expression of H-ras in human cytomegalovirus-transformed cells. Intervirology. 1994;37:321–329. doi: 10.1159/000150396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shen Y, Zhu H, Shenk T. Human cytomagalovirus IE1 and IE2 proteins are mutagenic and mediate “hit-and-run” oncogenic transformation in cooperation with the adenovirus E1A proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3341–3345. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doniger J, Muralidhar S, Rosenthal LJ. Human cytomegalovirus and human herpesvirus 6 genes that transform and transactivate. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:367–382. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.3.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cinatl J, Jr, Cinatl J, Vogel JU, Rabenau H, Kornhuber B, Doerr HW. Modulatory effects of human cytomegalovirus infection on malignant properties of cancer cells. Intervirology. 1996;39:259–269. doi: 10.1159/000150527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cinatl J, Jr, Vogel JU, Cinatl J, Weber B, Rabenau H, Novak M, Kornhuber B, Doerr HW. Long-term productive human cytomegalovirus infection of a human neuroblastoma cell line. Int J Cancer. 1996;65:90–96. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960103)65:1<90::AID-IJC16>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cinatl J, Jr, Cinatl J, Vogel JU, Kotchetkov R, Driever PH, Kabickova H, Kornhuber B, Schwabe D, Doerr HW. Persistent human cytomegalovirus infection induces drug resistance and alteration of programmed cell death in human neuroblastoma cells. Cancer Res. 1998;58:367–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cinatl J, Jr, Vogel JU, Kotchetkov R, Doerr HW. Oncomodulatory signals by regulatory proteins encoded by human cytomegalovirus: a novel role for viral infection in tumor progression. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2004;28:59–77. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castillo JP, Kowalik TF. HCMV infection: modulating the cell cycle and cell death. Int Rev Immunol. 2004;23:113–139. doi: 10.1080/08830180490265565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanchez V, Spector DH. Subversion of cell cycle regulatory pathways. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;325:243–262. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-77349-8_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hume AJ, Finkel JS, Kamil JP, Coen DM, Culbertson MR, Kalejta RF. Phosphorylation of retinoblastoma protein by viral protein with cyclin-dependent kinase function. Science. 2008;320:797–799. doi: 10.1126/science.1152095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song YJ, Stinski MF. Inhibition of cell division by the human cytomegalovirus IE86 protein: role of the p53 pathway or cyclin-dependent kinase 1/cyclin B1. J Virol. 2005;79:2597–2603. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.4.2597-2603.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pucci B, Kasten M, Giordano A. Cell cycle and apoptosis. Neoplasia. 2000;2:291–299. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luo MH, Fortunato EA. Long-term infection and shedding of human cytomegalovirus in T98G glioblastoma cells. J Virol. 2007;81:10424–10436. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00866-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cobbs CS, Soroceanu L, Denham S, Zhang W, Kraus MH. Modulation of oncogenic phenotype in human glioma cells by cytomegalovirus IE1-mediated mitogenicity. Cancer Res. 2008;68:724–730. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maussang D, Verzijl D, van Walsum M, Leurs R, Holl J, Pleskoff O, Michel D, van Dongen GA, Smit MJ. Human cytomegalovirus-encoded chemokine receptor US28 promotes tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13068–13073. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604433103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Furukawa T. A variant of human cytomegalovirus derived from a persistently infected culture. Virology. 1984;137:191–194. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(84)90023-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogura T, Tanaka J, Kamiya S, Sato H, Ogura H, Hatano M. Human cytomegalovirus persistent infection in a human central nervous system cell line: production of a variant virus with different growth characteristics. J Gen Virol. 1986;67:2605–2616. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-67-12-2605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murphy EA, Streblow DN, Nelson JA, Stinski MF. The human cytomegalovirus IE86 protein can block cell cycle progression after inducing transition into the S phase of permissive cells. J Virol. 2000;74:7108–7118. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.15.7108-7118.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hayashi ML, Blankenship C, Shenk T. Human cytomegalovirus UL69 protein is required for efficient accumulation of infected cells in the G1 phase of the cell cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2692–2696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050587597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang W, Cazacu S, Xiang C, Zenklusen JC, Fine HA, Berens M, Armstrong B, Brodie C, Mikkelsen T. FK506 binding protein mediates glioma cell growth and sensitivity to rapamycin treatment by regulating NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Neoplasia. 2008;10:235–243. doi: 10.1593/neo.07929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park DC, Yeo SG, Wilson MR, Yerbury JJ, Kwong J, Welch WR, Choi YK, Birrer MJ, Mok SC, Wong KK. Clusterin interacts with paclitaxel and confer paclitaxel resistance in ovarian cancer. Neoplasia. 2008;10:964–972. doi: 10.1593/neo.08604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Plati J, Bucur O, Khosravi-Far R. Dysregulation of apoptotic signaling in cancer: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. J Cell Biochem. 2008;104:1124–1149. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu H, Shen Y, Shenk T. Human cytomegalovirus IE1 and IE2 proteins block apoptosis. J Virol. 1995;69:7960–7970. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.7960-7970.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hsu CH, Chang MD, Tai KY, Yang YT, Wang PS, Chen CJ, Wang YH, Lee SC, Wu CW, Juan LJ. HCMV IE2-mediated inhibition of HAT activity downregulates p53 function. EMBO J. 2004;23:2269–2280. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Speir E, Modali R, Huang ES, Leon MB, Shawl F, Finkel T, Epstein SE. Potential role of human cytomegalovirus and p53 interaction in coronary restenosis. Science. 1994;265:391–394. doi: 10.1126/science.8023160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsai HL, Kou GH, Chen SC, Wu CW, Lin YS. Human cytomegalovirus immediate-early protein IE2 tethers a transcriptional repression domain to p53. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:3534–3540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanaka K, Zou JP, Takeda K, Ferrans VJ, Sandford GR, Johnson TM, Finkel T, Epstein SE. Effects of human cytomegalovirus immediate-early proteins on p53-mediated apoptosis in coronary artery smooth muscle cells. Circulation. 1999;99:1656–1659. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.13.1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lukac DM, Alwine JC. Effects of human cytomegalovirus major immediate-early proteins in controlling the cell cycle and inhibiting apoptosis: studies with ts13 cells. J Virol. 1999;73:2825–2831. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2825-2831.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCormick AL. Control of apoptosis by human cytomegalovirus. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;325:281–295. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-77349-8_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Michaelis M, Kotchetkov R, Vogel JU, Doerr HW, Cinatl J., Jr Cytomegalovirus infection blocks apoptosis in cancer cells. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61:1307–1316. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-3417-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Skaletskaya A, Bartle LM, Chittenden T, McCormick AL, Mocarski ES, Goldmacher VS. A cytomegalovirus-encoded inhibitor of apoptosis that suppresses caspase-8 activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:7829–7834. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141108798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCormick AL, Skaletskaya A, Barry PA, Mocarski ES, Goldmacher VS. Differential function and expression of the viral inhibitor of caspase 8—induced apoptosis (vICA) and the viral mitochondria—localized inhibitor of apoptosis (vMIA) cell death suppressors conserved in primate and rodent cytomegaloviruses. Virology. 2003;316:221–233. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goldmacher VS, Bartle LM, Skaletskaya A, Dionne CA, Kedersha NL, Vater CA, Han JW, Lutz RJ, Watanabe S, Cahir McFarland ED, et al. A cytomegalovirus-encoded mitochondria-localized inhibitor of apoptosis structurally unrelated to Bcl-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12536–12541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Norris KL, Youle RJ. Cytomegalovirus proteins vMIA and m38.5 link mitochondrial morphogenesis to Bcl-2 family proteins. J Virol. 2008;82:6232–6243. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02710-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Terhune S, Torigoi E, Moorman N, Silva M, Qian Z, Shenk T, Yu D. Human cytomegalovirus UL38 protein blocks apoptosis. J Virol. 2007;81:3109–3123. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02124-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moorman NJ, Cristea IM, Terhune SS, Rout MP, Chait BT, Shenk T. Human cytomegalovirus protein UL38 inhibits host cell stress responses by antagonizing the tuberous sclerosis protein complex. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3:253–262. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reeves MB, Davies AA, McSharry BP, Wilkinson GW, Sinclair JH. Complex I binding by a virally encoded RNA regulates mitochondria-induced cell death. Science. 2007;316:1345–1348. doi: 10.1126/science.1142984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soroceanu L, Akhavan A, Cobbs CS. Platelet-derived growth factor-alpha receptor activation is required for human cytomegalovirus infection. Nature. 2008;455:391–395. doi: 10.1038/nature07209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blaheta RA, Weich E, Marian D, Bereiter-Hahn J, Jones J, Jonas D, Michaelis M, Doerr HW, Cinatl J., Jr Human cytomegalovirus infection PC3 prostate carcinoma cell adhesion to endothelial cells and extracellular matrix. Neoplasia. 2006;8:807–816. doi: 10.1593/neo.06379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cobbs CS, Soroceanu L, Denham S, Zhang W, Britt WJ, Pieper R, Kraus MH. Human cytomegalovirus induces cellular tyrosine kinase signaling and promotes glioma cell invasiveness. J Neurooncol. 2007;85:271–280. doi: 10.1007/s11060-007-9423-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harkins L, Volk AL, Samanta M, Mikolaenko I, Britt WJ, Bland KI, Cobbs CS. Specific localisation of human cytomegalovirus nucleic acids and proteins in human colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2002;360:1557–1563. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11524-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Allart S, Martin H, Detraves C, Terrasson J, Caput D, Davrinche C. Human cytomegalovirus induces drug resistance and alteration of programmed cell death by accumulation of deltaN-p73alpha. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:29063–29068. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201974200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Blaheta RA, Beecken WD, Engl T, Jonas D, Oppermann E, Hundemer M, Doerr HW, Scholz M, Cinatl J., Jr Human cytomegalovirus infection of tumor cells downregulates NCAM (CD56): a novel mechanism for virus-induced tumor invasiveness. Neoplasia. 2004;6:323–331. doi: 10.1593/neo.03418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kopfstein L, Christofori G. Metastasis: cell-autonomous mechanisms versus contributions by the tumor microenvironment. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:449–468. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5296-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cruz-Monserrate Z, O'Connor KL. Integrin alpha 6 beta 4 promotes migration, invasion through Tiam1 upregulation, and subsequent Rac activation. Neoplasia. 2008;10:408–417. doi: 10.1593/neo.07868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hall CL, Dubyk CW, Riesenberger TA, Shein D, Keller ET, van Golen KL. Type I collagen receptor (alpha2beta1) signaling promotes prostate cancer invasion through RhoC GTPase. Neoplasia. 2008;10:797–803. doi: 10.1593/neo.08380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Streblow DN, Soderberg-Naucler C, Vieira J, Smith P, Wakabayashi E, Ruchti F, Mattison K, Altschuler Y, Nelson JA. The human cytomegalovirus chemokine receptor US28 mediates vascular smooth muscle cell migration. Cell. 1999;99:511–520. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81539-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Streblow DN, Vomaske J, Smith P, Melnychuk R, Hall L, Pancheva D, Smit M, Casarosa P, Schlaepfer DD, Nelson JA. Human cytomegalovirus chemokine receptor US28-induced smooth muscle cell migration is mediated by focal adhesion kinase and Src. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:50456–50465. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307936200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hoever G, Vogel JU, Lukashenko P, Hofmann WK, Komor M, Doerr HW, Cinatl J., Jr Impact of persistent cytomegalovirus infection on human neuroblastoma cell gene expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;326:395–401. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wojtukiewicz MZ, Sierko E, Klement P, Rak J. The hemostatic system and angiogenesis in malignancy. Neoplasia. 2001;3:371–384. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Goon PK, Lip GY, Boos CJ, Stonelake PS, Blann AD. Circulating endothelial cells, endothelial progenitor cells, and endothelial microparticles in cancer. Neoplasia. 2006;8:79–88. doi: 10.1593/neo.05592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Murayama T, Ohara Y, Obuchi M, Khabar KS, Higashi H, Mukaida N, Matsushima K. Human cytomegalovirus induces interleukin-8 production by a human monocytic cell line, THP-1, through acting concurrently on AP-1— and NF-kappaB—binding sites of the interleukin-8 gene. J Virol. 1997;71:5692–5695. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5692-5695.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Murayama T, Mukaida N, Sadanari H, Yamaguchi N, Khabar KS, Tanaka J, Matsushima K, Mori S, Eizuru Y. The immediate early gene 1 product of human cytomegalovirus is sufficient for up-regulation of interleukin-8 gene expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;279:298–304. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cinatl J, Jr, Kotchetkov R, Scholz M, Cinatl J, Vogel JU, Hernáiz Driever P, Doerr HW. Human cytomegalovirus infection decreases expression of thrombospondin-1 independent of the tumor suppressor protein p53. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:285–292. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65122-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lee K, Jeon K, Kim JM, Kim VN, Choi DH, Kim SU, Kim S. Downregulation of GFAP, TSP-1, and p53 in human glioblastoma cell line, U373MG, by IE1 protein from human cytomegalovirus. Glia. 2005;51:1–12. doi: 10.1002/glia.20179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bentz GL, Yurochko AD. Human CMV infection of endothelial cells induces an angiogenic response through viral binding to EGF receptor and beta1 and beta3 integrins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:5531–5536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800037105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dumortier J, Streblow DN, Moses AV, Jacobs JM, Kreklywich CN, Camp D, Smith RD, Orloff SL, Nelson JA. Human cytomegalovirus secretome contains factors that induce angiogenesis and wound healing. J Virol. 2008;82:6524–6535. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00502-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Drake CG, Jaffee E, Pardoll DM. Mechanisms of immune evasion by tumors. Adv Immunol. 2006;90:51–81. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(06)90002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nazarenko I, Marhaba R, Reich E, Voronov E, Vitacolonna M, Hildebrand D, Elter E, Rajasagi M, Apte RN, Zöller M. Tumorigenicity of IL-1alpha— and IL-1beta—deficient fibrosarcoma cells. Neoplasia. 2008;10:549–562. doi: 10.1593/neo.08286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cinatl J, Jr, Scholz M, Doerr HW. Role of tumor cell immune escape mechanisms in cytomegalovirus-mediated oncomodulation. Med Res Rev. 2005;25:167–185. doi: 10.1002/med.20018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Powers C, DeFilippis V, Malouli D, Früh K. Cytomegalovirus immune evasion. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;325:333–359. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-77349-8_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nelson JA. Small RNAs and large DNA viruses. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2630–2632. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr0706718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wilkinson GW, Tomasec P, Stanton RJ, Armstrong M, Prod'homme V, Aicheler R, McSharry BP, Rickards CR, Cochrane D, Llewellyn-Lacey S, et al. Modulation of natural killer cells by human cytomegalovirus. J Clin Virol. 2008;41:206–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cretney E, Degli-Esposti MA, Densley EH, Farrell HE, Davis-Poynter NJ, Smyth MJ. m144, a murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV)—encoded major histocompatibility complex class I homologue, confers tumor resistance to natural killer cell-mediated rejection. J Exp Med. 1999;190:435–444. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.3.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kotenko SV, Saccani S, Izotova LS, Mirochnitchenko OV, Pestka S. Human cytomegalovirus harbors its own unique IL-10 homolog (cmvIL-10). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1695–1700. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Spencer JV, Lockridge KM, Barry PA, Lin G, Tsang M, Penfold ME, Schall TJ. Potent immunosuppressive activities of cytomegalovirus-encoded interleukin-10. J Virol. 2002;76:1285–1292. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.3.1285-1292.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jenkins C, Garcia W, Godwin MJ, Spencer JV, Stern JL, Abendroth A, Slobedman B. Immunomodulatory properties of a viral homolog of human interleukin-10 expressed by human cytomegalovirus during the latent phase of infection. J Virol. 2008;82:3736–3750. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02173-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Michelson S, Alcami J, Kim SJ, Danielpour D, Bachelerie F, Picard L, Bessia C, Paya C, Virelizier JL. Human cytomegalovirus infection induces transcription and secretion of transforming growth factor beta 1. J Virol. 1994;68:5730–5737. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.5730-5737.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kwon YJ, Kim DJ, Kim JH, Park CG, Cha CY, Hwang ES. Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) infection in osteosarcoma cell line suppresses GM-CSF production by induction of TGF-beta. Microbiol Immunol. 2004;48:195–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2004.tb03505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wick W, Naumann U, Weller M. Transforming growth factor-beta: a molecular target for the future therapy of glioblastoma. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12:341–349. doi: 10.2174/138161206775201901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Alcami J, Paya CV, Virelizier JL, Michelson S. Antagonistic modulation of human cytomegalovirus replication by transforming growth factor beta and basic fibroblastic growth factor. J Gen Virol. 1993;74:269–274. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-2-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yoo YD, Chiou CJ, Choi KS, Yi Y, Michelson S, Kim S, Hayward GS, Kim SJ. The IE2 regulatory protein of human cytomegalovirus induces expression of the human transforming growth factor beta1 gene through an Egr-1 binding site. J Virol. 1996;70:7062–7070. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.7062-7070.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tabata T, Kawakatsu H, Maidji E, Sakai T, Sakai K, Fang-Hoover J, Aiba M, Sheppard D, Pereira L. Induction of an epithelial integrin alphavbeta6 in human cytomegalovirus—infected endothelial cells leads to activation of transforming growth factor-beta1 and increased collagen production. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:1127–1140. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fortunato EA, Spector DH. Viral induction of site-specific chromosome damage. Rev Med Virol. 2003;13:21–37. doi: 10.1002/rmv.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jefford CE, Irminger-Finger I. Mechanisms of chromosome instability in cancers. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2006;59:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Privette LM, Weier JF, Nguyen HN, Yu X, Petty EM. Loss of CHFR in human mammary epithelial cells causes genomic instability by disrupting the mitotic spindle assembly checkpoint. Neoplasia. 2008;10:643–652. doi: 10.1593/neo.08176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hartmann M, Brunnemann H. Chromosome aberrations in cytomegalovirus-infected human diploid cell culture. Acta Virol. 1972;16:176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Deng CZ, AbuBakar S, Fons MP, Boldogh I, Albrecht T. Modulation of the frequency of human cytomegalovirus—induced chromosome aberrations by camptothecin. Virology. 1992;189:397–401. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90724-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Deng CZ, AbuBakar S, Fons MP, Boldogh I, Hokanson J, Au WW, Albrecht T. Cytomegalovirus-enhanced induction of chromosome aberrations in human peripheral blood lymphocytes treated with potent genotoxic agents. Environ Mol Mutagen. 1992;19:304–310. doi: 10.1002/em.2850190407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fortunato EA, Dell'Aquila ML, Spector DH. Specific chromosome 1 breaks induced by human cytomegalovirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:853–858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Baumgartner M, Schneider R, Auer B, Herzog H, Schweiger M, Hirsch-Kauffmann M. Fluorescence in situ mapping of the human nuclear NAD+ ADP-ribosyltransferase gene (ADPRT) and two secondary sites to human chromosomal bands 1q42, 13q34, and 14q24. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1992;61:172–174. doi: 10.1159/000133400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Li YS, Ramsay DA, Fan YS, Armstrong RF, Del Maestro RF. Cytogenetic evidence that a tumor suppressor gene in the long arm of chromosome 1 contributes to glioma growth. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1995;84:46–50. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(95)00065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bièche I, Champème MH, Lidereau R. Loss and gain of distinct regions of chromosome 1q in primary breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1995;1:123–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cobbs CS, Harkins L, Samanta M, Gillespie GY, Bharara S, King PH, Nabors LB, Cobbs CG, Britt WJ. Human cytomegalovirus infection and expression in human malignant glioma. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3347–3350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Samanta M, Harkins L, Klemm K, Britt WJ, Cobbs CS. High prevalence prevalence of human cytomegalovirus in prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and prostatic carcinoma. J Urol. 2003;170:998–1002. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000080263.46164.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mitchell DA, Xie W, Schmittling R, Learn C, Friedman A, McLendon RE, Sampson JH. Sensitive detection of human cytomegalovirus in tumors and peripheral blood of patients diagnosed with glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2008;10:10–18. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2007-035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Prins RM, Cloughesy TF, Liau LM. Cytomegalovirus immunity after vaccination with autologous glioblastoma lysate. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:539–541. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0804818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Scheurer ME, Bondy ML, Aldape KD, Albrecht T, El-Zein R. Detection of human cytomegalovirus in different histological types of gliomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;116:79–86. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0359-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]