Abstract

Methamphetamine is one of the most addictive and neurotoxic drugs of abuse. It produces large elevations in extracellular dopamine in the striatum through vesicular release and inhibition of the dopamine transporter. In the U.S. abuse prevalence varies by ethnicity with very low abuse among African Americans relative to Caucasians, differentiating it from cocaine where abuse rates are similar for the two groups. Here we report the first comparison of methamphetamine and cocaine pharmacokinetics in brain between Caucasians and African Americans along with the measurement of dopamine transporter availability in striatum. Methamphetamine’s uptake in brain was fast (peak uptake at 9 minutes) with accumulation in cortical and subcortical brain regions and in white matter. Its clearance from brain was slow (except for white matter which did not clear over the 90 minutes) and there was no difference in pharmacokinetics between Caucasians and African Americans. In contrast cocaine’s brain uptake and clearance were both fast, distribution was predominantly in striatum and uptake was higher in African Americans. Among individuals, those with the highest striatal (but not cerebellar) methamphetamine accumulation also had the highest dopamine transporter availability suggesting a relationship between METH exposure and DAT availability. Methamphetamine’s fast brain uptake is consistent with its highly reinforcing effects, its slow clearance with its long lasting behavioral effects and its widespread distribution with its neurotoxic effects that affect not only striatal but also cortical and white matter regions. The absence of significant differences between Caucasians and African Americans suggests that variables other than methamphetamine pharmacokinetics and bioavailability account for the lower abuse prevalence in African Americans.

Introduction

Methamphetamine (METH) is considered among the most addictive of the drugs of abuse. Its powerful addictive properties, coupled with its broad availability have led to significant increases in both its abuse and in the number of associated medical complications in many areas of the world (Rawson and Condon, 2007; Barr et al., 2006). In the United States the prevalence varies by region and ethnicity, being very low among African Americans (Sexton et al., 2005; Iritani et al., 2007). This is in contrast to cocaine for which the prevalence rates for abuse and dependence are equivalent in Caucasians and African Americans (SAMHSA, 2003). Among the drugs of abuse, METH, which elevates dopamine (DA) by both inhibiting its reuptake as well as releasing it from vesicles (Rothman et al., 2001), is one of the most potent. It produces very large increases in DA concentration in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) (Camp et al., 1994), which is the mechanism believed to underlie the reinforcing effects of addictive drugs (DiChiara and Imperato, 1988). However, the reinforcing effects of drugs are not just a function of their potency in increasing DA in NAc but also of the rate at which they increase it; that is, the faster the increases, the stronger their reinforcing effects (Balster and Schuster, 1973). We have previously shown that cocaine (measured with [11C]cocaine) entered the brain very rapidly, which would explain why it is such a reinforcing drug (Fowler et al., 1989). Moreover we corroborated a temporal correspondence between the fast uptake of the drug in brain and the subjective experience of the ‘high’ (Volkow et al., 1997).

Here we use PET and [11C]d-methamphetamine administered at tracers doses to measure the pharmacokinetics and distribution of METH in the human brain. We also investigated whether differences in the pharmacokinetics (PK) of METH in the brain could explain the large differences in the prevalence rate of abuse of METH between Caucasians and African Americans. We hypothesized, based on our prior studies with [11C]d-methamphetamine in the baboon brain (Fowler et al., 2007), that METH uptake in the brain would be very fast and similar to that of cocaine and that, as per our prior studies with stimulant drugs, its fast uptake would be associated with its reinforcing effects (assessed by subjective descriptors of ‘high’) (Volkow et al., 1995). We also predicted that uptake of METH in brain would be higher and faster in Caucasians than in African Americans. In this same group of subjects, we also measured cocaine PK with [11C]cocaine for comparison with METH PK and to test the hypothesis that dopamine transporter (DAT) availability (assessed with the distribution volume ratio (DVR) of striatum to cerebellum obtained from the [11C]cocaine images (Logan et al., 1990) would contribute to the intersubject variability in METH uptake. Specifically we predicted that the higher DAT availability would be associated with greater METH uptake in brain.

Materials and methods

Volunteers

This study was carried out at Brookhaven National Laboratory and approved by the local Institutional Review Board (Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects, Stony Brook University). Written informed consent was obtained from all of the participants prior to the study. Nineteen normal healthy men (9 Caucasians and 10 African Americans), average age 37±7 years (range 24-49) were recruited by word of mouth and newspaper advertisements and enrolled in this study. Inclusion criteria were non-smoking males able to understand and give informed consent, age 18-50 years. Excluded were those subjects who were urine positive for psychoactive drugs (including PCP, cocaine, amphetamine, opiates, barbiturates, benzodiazepines and THC); who had clinically significant abnormal laboratory values; past or present history of medical illness or neurological or psychiatric disease; use of antidepressant, antipsychotic, stimulants or chronic anxiolytic medications in the past one month; head trauma with loss of consciousness for more than 30 minutes; past or present or past history of substance abuse including illicit substances, alcohol and nicotine.

Radiotracer Synthesis

[11C]d-Methamphetamine was prepared from d- amphetamine and [11C]methyl iodide using an adaptation of the literature method (Inoue et al., 1990) as described previously (Fowler et al., 2007). Dynamic PET imaging was carried out on a Siemen’s HR+ high resolution, whole body PET scanner (4.5×4.5×4.8 mm FWHM at center of field of view) in 3D acquisition mode, 63 planes. For all scans, a transmission scan was obtained with a 68Ge rotating rod source before the emission scan to correct for attenuation before each radiotracer injection. The specific activity of [11C]d-methamphetamine was 0.32± 0.28 mCi/nmol at time of injection and the dose injected averaged 7.1±0.37 mCi). The radiochemical purity was >98%. Scanning was carried out for 90 minutes with the following time frames (1×10 sec; 12×5 sec; 1×20 sec; 1×30 sec; 8×60 sec; 4×300 sec; 8×450 sec).

[11C](-)-Cocaine was synthesized from nor-cocaine (NIDA Research Technology Branch) according to the literature method (Fowler et al., 1989). Radiochemical purity was >98% and specific activity was 0.53± 0.36 mCi/nmol at end of synthesis and the dose injected averaged 6.72 ± 0.58 mCi. Scanning was carried out for 54 min with the following time frames (1 × 10 sec; 12 × 5 sec; 1 × 20 sec; 1 × 30 sec; 4 × 60 sec; 4 × 120 sec; 8 × 300 sec).

Typically, the two studies were performed two hours apart. For both [11C]dmethamphetamine and [11C]cocaine the concentration of parent radiotracer in the arterial plasma was measured (Fowler et al., 2007; Alexoff et al., 1995).

Image processing and data analysis

Time frames were summed over the experimental period (90 min for [11C]dmethamphetamine and 54 min for [11C](-)-cocaine), the summed images were resliced along the AC-PC line and planes were summed in groups of two for the purpose of region of interest (roi) placement. For [11C]d-methamphetamine, roi’s were placed on the caudate, dorsal putamen, ventral striatum, thalamus and the frontal, temporal and parietal cortices, cingulate gyrus, cerebellum and white matter and then projected onto the dynamic images. For the [11C]cocaine scans, roi’s were placed over the caudate, putamen, thalamus, cerebellum and white matter and then projected onto the dynamic images to obtain time activity curves. Regions occurring bilaterally were averaged. Carbon-11 concentration in each region of interest was divided by the injected dose to obtain the concentrations of C-11 vs. time which, along with the time course of the arterial concentration of the radiotracer, were used to calculate the DV’s using a graphical analysis method for reversible systems (Logan et al., 1990). For [11C]cocaine we computed the ratio of the DV ratio (DVR) in caudate, putamen and thalamus to that in the cerebellum. The DVR-1 for putamen, which corresponds to Bmax/Kd, was used as an estimate of DAT availability. The averaged time activity curves for the putamen, thalamus, cerebellum and white matter were compared for [11C]methamphetamine and [11C]cocaine. For [11C]dmethamphetamine, the area under the time activity curve (% injected dose/cc vs time) (AUC) in the ventral striatum (normalized to the AUC for the plasma) was also obtained.

In order to examine whether there were PK differences for Caucasians vs African Americans, we compared the following parameters for [11C]d-methamphetamine and for [11C]cocaine: DV’s for the caudate, putamen, thalamus and cerebellum; time to peak and the % clearance at the end of study; areas under the time-activity curve for plasma. For all subjects, correlation analyses were also performed between [11C]d-methamphetamine uptake (AUC for the putamen), normalized to the AUC for the plasma and DAT availability (DVR-1) in the putamen as measured with [11C]cocaine (Logan et al., 1990). In order to compare the time course of the uptake to the time course of the ‘high’ reported previously (Newton et al., 2006), the time-activity curve (% injected dose/cc) in the ventral striatum was divided by the peak uptake value so that the values for each time point could be presented as % of peak. The time course for the ‘high’ for a pharmacological dose of methamphetamine reported previously (Newton et al., 2006) was normalized to the peak value for comparison to the C-11 uptake.

Comparisons between groups were made using Student’s t test (unpaired) and differences within individuals were compared with Student’s t-test (paired). Pearson product moment correlations were used to assess the association between METH AUC in putamen and DAT availability.

Results

Distribution of and kinetics of METH and cocaine

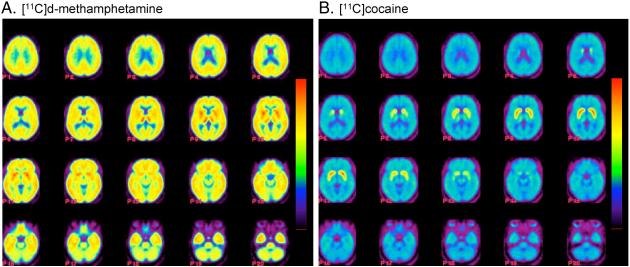

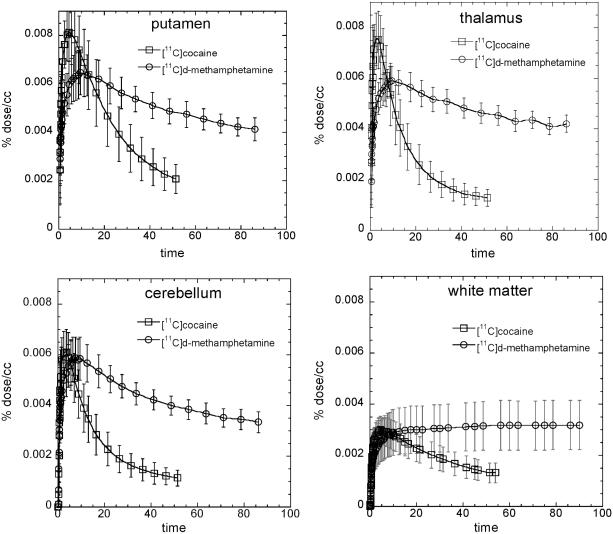

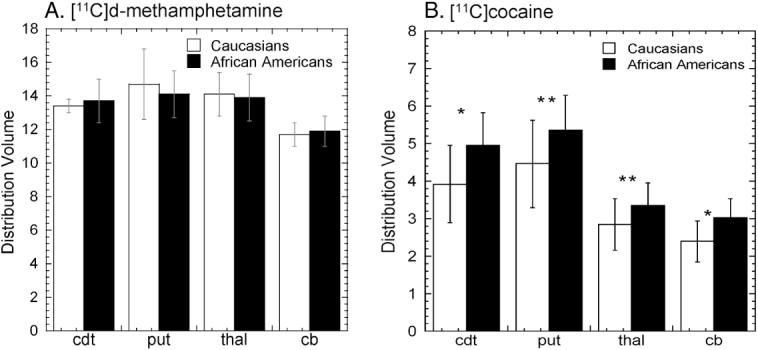

Carbon-11 was widely distributed to both cortical and subcortical brain regions after the intravenous administration of [11C]d-methamphetamine in contrast to [11C]cocaine which was predominantly concentrated in the striatum (see Figure 1A,B for averaged images and Figure 2 comparing distribution volumes (DV) for the two drugs in Caucasians and African Americans). For all subjects, the peak uptake in striatum was lower for METH than for cocaine and also occurred later and its clearance was also slower (Table 1). The time-activity curves for METH and cocaine for different brain regions are shown in Figure 3. For METH cortical and subcortical brain regions cleared over the time of the imaging session with clearance half times ∼100 minutes contrasting with cocaine which cleared much more rapidly. There was no difference in rate of clearance between the dorsal and ventral striatum (data not shown). For METH the DV’s in the caudate, putamen and the thalamus were significantly greater than those in the cerebellum (p=0.0001). There was no observable clearance of [11C]d-methamphetamine from white matter over the 90 minute imaging session whereas for cocaine the rate of clearance in white matter was similar to that of gray matter regions. The lack of clearance of C-11 sets white matter apart from other brain regions and may reflect the higher lipid character of white matter relative to gray matter. Interestingly, the lack of white matter clearance probably explains the relatively higher concentration of METH in white matter from autopsy samples from human methamphetamine abusers (Kalasinsky et al., 2001). To the extent that there is white matter in cortical and subcortical regions it could also contribute to slowing the clearance of [11C]dmethamphetamine in these brain regions

Fig. 1.

(A) Images for [11C]d-methamphetamine showing transaxial planes from the top to the head to the base of the skull; (B) images for [11C]cocaine showing transaxial planes from the top to the head to the base of the skull. Distribution volume images were constructed for each subject (n=19) and all of the images were normalized to the SPM 99 atlas (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/) and averaged. We use a rainbow color bar where red corresponds to a DV of 16 cc mL-1 for the [11C]d-methamphetamine images and 6 cc mL-1 for the [11C]cocaine images.

Fig. 2.

(A) Average distribution volumes ± sdm for [11C]d-methamphetamine for Caucasians (n=9) and African Americans (n=10). Unpaired t-test revealed no difference between the two groups. We note that for both groups the DV’s in the caudate, putamen and the thalamus were significantly greater than those in the cerebellum (p=0.0001). (B) average distribution volumes ± sdm for [11C]cocaine for Caucasians and African Americans. Unpaired t tests revealed significantly higher DV for the caudate and cerebellum (p<0.05) with a trend for the putamen and thalamus (p=0.09) (left panel) for the African Americans. (cdt=caudate; put=putamen, thal=thalamus; cb=cerebellum).

Table 1.

Comparison of peak uptake, time to peak and clearance for [11C]d-methamphetamine and [11C]cocaine for all subjects

| Parameter | [11C]d-methamphetamine (n=19) |

[11C]cocaine (n=19) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak uptake (% dose/cc) | 0.0065±0.001 | 0.0083±0.0012 | 0.0001 |

| Peak time (min) | 9.4±1.5 | 4.5±1.1 | 0.0001 |

| % remaining @ time | 63.9 @ 86 min | 24.9 @ 51 min | 0.0001 |

Fig. 3.

Average time-activity curves ±sdm for [11C]d-methamphetamine and [11C]cocaine in putamen, thalamus, cerebellum and white matter. Time-activity curves were generated for each subject and an average value ± sdm was obtained for each time point combining data from all subjects (n=19).

For [11C]d-methamphetamine, the appearance of labeled metabolites in arterial plasma was slow with 82 and 67 % of the total carbon-11 present as parent radiotracer at 30 and 90 min respectively. The appearance of labeled metabolites in plasma for [11C]cocaine was faster than for [11C]d-methamphetamine with only 43 and 31 % was present in plasma as parent radiotracer at 30 and 54 minutes respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Analysis of arterial plasma samples for [11C]d-methamphetamine (n=19) and [11C]cocaine (n=19)

| Time after injection (min) |

% as [11C]d- methamphetamine |

Time after injection (min) |

% as [11C]cocaine |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 96.6±1.1 | 1 | 97.4±1.5 |

| 5 | 94.1±3.2 | 5 | 92.8±2.6 |

| 10 | 91.8±3.7 | 10 | 75.1±5.9 |

| 20 | 85.3±7.0 | 20 | 52.1±7.0 |

| 30 | 81.7±6.4 | 30 | 42.7±5.0 |

| 60 | 70.8±9.6 | 45 | 34.7±4.2 |

| 90 | 66.8±7.4 | 54 | 31.3±4.5 |

Comparison of d-Methamphetamine kinetics in ventral striatum to the time course of the behavioral effects of a pharmacological dose of methamphetamine

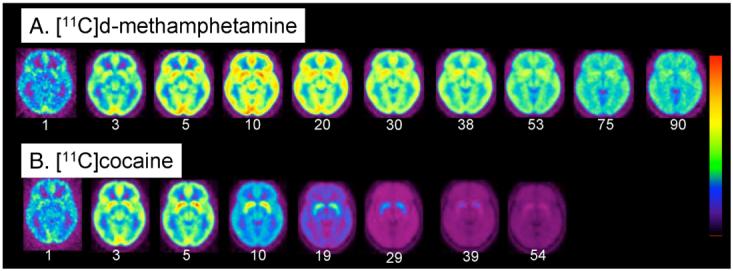

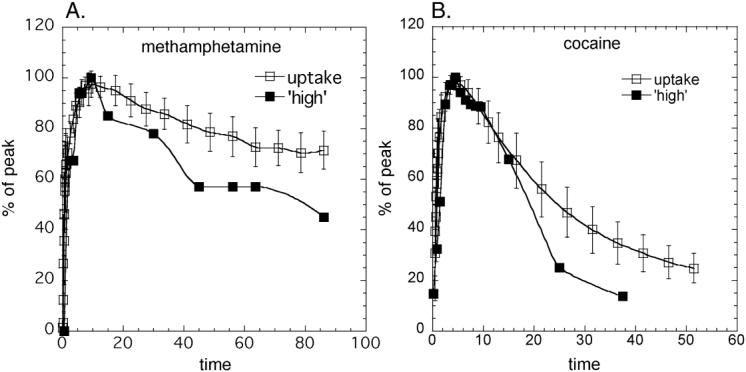

Averaged time-frame images for [11C]d-methamphetamine and [11C]cocaine in the plane of the ventral striatum over the time of the study show that [11C]d-methamphetamine peaks later and clears more slowly than [11C]cocaine (Figure 4). METH pharmacokinetics in ventral striatum paralleled the time course of self-reported ‘high’ after pharmacological doses of METH from studies done in methamphetamine abusers (Newton et al., 2006) (Figure 5). For comparison we also show the averaged time-activity curve for [11C]cocaine in striatum (from the present study) vs the ‘high’ from a pharmacological dose of cocaine measured previously (Volkow et al., 1997).

Fig. 4.

(A) Averaged images of [11C]d-methamphetamine (n=19) at the level of the striatum at different time frames over a 90 minute imaging session; (B) averaged images of [11C]cocaine (n=19) (bottom row) at the level of the putamen over a 54 minute imaging session. Note that [11C]cocaine peaks earlier and clears faster than [11C]d-methamphetamine. The time (minutes) for each frame is indicated below the image. We use a rainbow color bar where red represents the highest uptake and purple the lowest. The [11C]d-methamphetamine images, red corresponds to 0.006% injected dose/cc whereas for the [11C]cocaine images, red corresponds to 0.008% of the injected dose/cc. The dynamic images from both the [11C]d-methamphetamine and [11C]cocaine studies were normalized to the SPM 99 atlas (http://www.fil.ion.ucl. ac.uk/spm/) so that individual time frames could be averaged across subjects. The average time frame data was obtained by weighting each image by the factor f=avg dose/dose subj, summing over subjects and dividing by the number of subjects.

Fig. 5.

(A) Averaged time-activity curves for [11C]d-methamphetamine uptake in the ventral striatum (n=19) along with the time course of the ‘high’ (Newton et al., 2006); (B) Averaged time-activity curves for [11C]cocaine uptake in the putamen (n=19) along with the time course of the ‘high’ (Volkow et al. 1997). Both the time-activity curves and the time course for the ‘high’ were normalized to the highest value for presentation.

Comparison of the METH PK and cocaine PK in Caucasians and African Americans

There were no differences in [11C]d-methamphetamine distribution or pharmacokinetics between Caucasians and African Americans (Figure 2A and Table 3). However, in comparing the time-activity curves for [11C]cocaine for the putamen in Caucasians and African Americans, we found that peak uptake in the brain occurred later and the percentage of [11C]cocaine remaining at the end of the study was significantly higher for African Americans than for Caucasians (Table 3). The DV’s for the striatum (caudate and putamen), thalamus and cerebellum were also greater for African Americans than for Caucasians for [11C]cocaine (Figure 2B) though there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in DAT availability (DVR-1) (0.87±0.19 vs 0.77±0.12 ml cc-1, p=0.22). There were also no significant differences between the AUC for the time-activity curve for arterial plasma for either [11C]dmethamphetamine or [11C]cocaine for the two groups (data not shown).

Table 3.

Comparison of [11C]d-methamphetamine and [11C]cocaine time to peak uptake and the % remaining at end of study for the putamen for Caucasians (n=9) and African Americans (n=10)

| Parameter | Caucasians | African Americans | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| [11C]d-methamphetamine | |||

| Time to Peak (min) | 8.3±1.1 | 9.9±2.7 | NS |

| % remaining at 90 min | 63.8±8.4 | 64±9.8 | NS |

| [11C]cocaine | |||

| Time to Peak (min) | 3.83±0.97 | 5.05±0.96 | 0.014 |

| % remaining at 54 min | 21.45±5.1 | 28.02±5.1 | 0.009 |

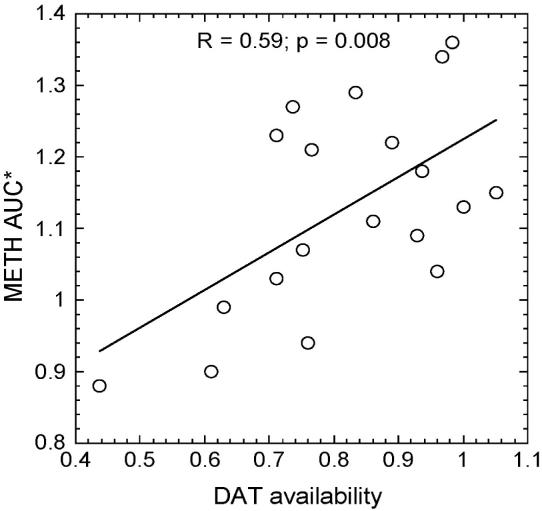

Correlation of the brain uptake of d-methamphetamine to DAT availability

Dopamine transporter availability (DVR-1) correlated with METH AUC for the putamen (normalized to the plasma AUC) (R=0.59; p=0.008) (Figure 6) but not for the cerebellum (R=0.06; p=0.81).

Fig. 6.

Correlation plot between the AUC (*normalized for the plasma AUC) for the [11C]dmethamphetamine time-activity curve in the putamen and DAT availability in putamen (R=0.59; p=0.008).

Discussion

Methamphetamine’s powerful addictive properties, its toxicity and its ready availability combine to create a sense of urgency to understand its behavioral and toxic effects. At the same time, reports that the rate of METH abuse among African Americans is lower than that for Caucasians has led us to question whether there are differences in bioavailability or PK that mediate this effect. The major findings from this study are that (1) d-methamphetamine has a relatively rapid and persistent distribution across brain regions with slow clearance from gray matter and no observable clearance from white matter regions which distinguish it from cocaine; (2) the kinetics in ventral striatum (where the nucleus accumbens is located) follow a similar time course to the ‘high’ reported from a pharmacological dose of d-methamphetamine (data from Newton et al., 2006); (3) Caucasians and African Americans do not differ in the PK or bioavailability of [11C]d-methamphetamine in brain though the two groups differ in [11C]cocaine’s PK and bioavailability and; (4) METH uptake in striatum but not the cerebellum over the time course of the study correlated with DAT availability. This suggests that differences in DAT availability between subjects may account for some of the inter-subject variability in METH exposure in striatum, which is the main target for METH dopaminergic effects. Since METH’s dopaminergic effects are implicated in its reinforcing properties, the differences in DAT availability is likely to contribute to variability in METH’s reinforcing effects.

[11C]d-Methamphetamine distributed widely in the human brain with high and persistent uptake in both subcortical and cortical areas (Figure 1A). This is similar to our recent findings in the non-human primate brain (Fowler et al., 2007) and to earlier studies in rat brain (O’Neil et al., 2006; Segal et al., 2005) after intravenous MET administration and to human autopsy samples from methamphetamine abusers (Kalasinksy et al., 2001) but different from [11C]cocaine (Figure 1B). The highest peak uptake of METH was in the putamen (average peak uptake ∼ 0.0065%/cc) whereas the lowest peak uptake occurred in the white matter (∼ 0.003%/cc). After iv administration, 7-8% of the injected dose accumulated in the brain within 10 minutes. Though the present studies were done at tracer doses, we can use this information to estimate that a typical abused dose of 30 mg of METH would result in a brain accumulation of ∼ 2.5 mg of METH (∼14 microM). Methamphetamine’s high concentration and persistence in brain and its ability to stimulate release and inhibit reuptake of DA (Rothman et al., 2001) would be predicted to lead to an elevation of DA (and other neurotransmitters) potentially leading to its intense behavioral effects and producing oxidative stress and damage throughout the brain (Volz et al., 2007).

Several studies have documented neurochemical, metabolic and morphological abnormalities in methamphetamine abusers and in animals exposed to methamphetamine that are not limited to brain regions containing DA cells and their terminals, implicating non-DA mechanisms of METH toxicity (Ernst et al., 2000; Volkow et al., 2001a; Thompson t al., 2004; Chung et al., 2007; Kuczenski et al., 2007). The present study which documents the METH distributes to many brain regions (Figure 1A) as well as prior studies documenting the relatively even distribution of METH in autopsy samples from methamphetamine abusers (Kalisinsky et al, 2001) adds to the increasing evidence that the pharmacological effects of METH are complex and involve different neurotransmitters and neuromodulators (Weinshenker et al., 2007) and suggests an association with the widespread disposition of the drug. New evidence in postmortem brains of METH abusers shows the presence of the lipid peroxidation products, 4-hydroxynonenal and malondialdehyde that is most prominent in striatum (caudate), intermediate in frontal cortex and absent in cerebellum (Fitzmaurice et al., 2006). We note that the distribution of METH differs from that of cocaine, which concentrates mostly in striatum and, unlike METH, clears rapidly (Figure 1B) (Fowler et al., 1989). Thus the brain exposure and presumably the neurotoxicity of METH are expected to differ from those of cocaine.

In this study we documented peak concentration of METH in putamen at ∼ 9 minutes after its intravenous administration (Figures 3 and 4). This tracks the onset of peak behavioral effects produced by smoked, and intravenous METH, which occur within 9-18 min of its administration (Newton et al., 2006; Cook et al., 1993). The rapid rate of entry into the brain is likely to contribute to the powerful reinforcing effects of METH since the rate at which drugs of abuse get into the brain plays a key role in reinforcement; the faster the uptake the stronger its reinforcing effects (Balster and Schuster, 1973). This, in turn, explains why smoking and intravenous injection are the routes of administration that produce the most pleasurable responses to drugs of abuse (Volkow et al., 2000). Moreover the correspondence between the fast uptake of METH in the ventral striatum and the time course for the self-reports of ‘high’ after intravenous METH (Newton et al., 2006) suggests a relationship between METH’s pharmacokinetics and its pharmacodynamic effects including the time course of its reinforcing effects in humans. The faster rate of uptake of cocaine vs METH in brain corresponds well with the fact that the self-reported ‘high’ occurs faster after intravenous cocaine (4-6 minutes (Volkow et al., 1997) than after intravenous METH (approximately 9 min (Figures 4 and 5)).

We found that the clearance of METH also roughly corresponded with the temporal course of the decline in the experience of the ‘high’. This indicates that it is the PK of the drug in the brain, which is the important variable in determining the duration of its behavioral effects when administered at a pharmacologically active dose. The longer duration of the METH in the brain is associated with the long lasting ‘high’ reported previously (Newton et al., 2006). The temporal relationship between the time courses of the uptake and clearance of [11C]dmethamphetamine in the brain and the time course of the intensity of the ‘high’ is similar to the relationship between these two variables for cocaine (Volkow et al., 1997). The much slower brain clearance of METH relative to cocaine is likely to reflect differences in bioavailability and non-specific effects (Fowler et al., 2007). The longer duration of action along with its potent effects in raising DA are likely to contribute to the greater neurotoxicity to DA cells reported for METH than for cocaine. Indeed imaging studies have shown decrements in DAT in METH but not in cocaine abusers (Volkow et al., 2001b; Volkow et al., 1996). We note the terminal half life of d-methamphetamine in human plasma after iv was reported to be 13.1 hr (Cook et al., 1993) which is far longer than the brain clearance rate or the arterial clearance, which we report here. However, the PET study covered the early part of the time curve from a few seconds to 90 minutes whereas the plasma half life reported in the previous study (Cook et al, 1993) was measured during a 2 minute to 48 hour period capturing the terminal clearance phase. Interestingly, the putamen to plasma ratio in the human peaked 16:1 at 20 minutes post injection and plateaued thereafter (data not shown) which is comparable to the published rat PK for d-METH which also peaked at 20 minutes reaching a similar value of 13:1 (Riviere et al, 2000).

An important but not well understood aspect in the epidemiology of METH abuse is the low prevalence rates in African Americans relative to Caucasians (Sexton et al., 2005; Iritani et al., 2007). Several explanations have been proposed including a higher preference and accessibility to cocaine in African Americans, dislike for METH’s long-lasting stimulant effects and limited access to METH (Sexton et al., 2005). However, we questioned the possibility that biological factors affecting METH bioavailability and PK (i.e metabolism, excretion) could contribute to these differences. The similarities in the regional distribution and PK of METH in brain between African Americans and Caucasians (Figure 2A; Table 3) indicates that factors other than differences in bioavailability underlie the lower use of METH among African Americans. In contrast, there were significant differences between the ethnic groups for cocaine; cocaine peaked later and cleared more slowly in African Americans than in Caucasians and brain distribution volumes (all regions) for cocaine were also higher for African Americans (Table 3 and Figure 2B). Although we do not know whether there is any clinical significance due to these differences, this surprising observation raises the question of whether differences in bioavailability between Caucasians and African Americans have any epidemiological or clinical manifestation. It also merits further investigation in a larger group of subjects and highlights the importance of considering and reporting ethnicity as a variable in clinical research studies and in matching ethnicity between control and experimental subjects.

The heterozygous deletion of DAT attenuates the behavioral effects of METH (Fukushima et al., 2007) suggesting that DAT (as well as VMAT2) play a role in its neurotoxicity (Fumagalli et al., 1998; Fumagalli et al., 1999). Given the role of the DAT in the behavioral effects of METH and assuming that higher METH exposure is an important variable in the behavioral effects of the drug, we examined whether there would be an association between DAT availability (as measured using the DVR-1 with [11C]cocaine) and METH exposure using the area under the time-activity curve (AUC) for the putamen as the measure of METH exposure. Interestingly, the AUC varied by almost 2-fold for all individuals. Subjects with the highest AUC for METH in the putamen also had the highest DAT availability (Figure 6). We note that the AUC for the cerebellum for METH does not correlate with DAT availability suggesting a specific association with striatum and not a global effect. These data suggest that individual DAT availability in striatum may play a role in the variability in individual’s METH exposure.

There are potential study limitations that need to be addressed. For example, we measured METH PK at tracer doses whereas METH abusers use the drug at a typical dose of 0.5 mg/kg. This raises a question as to whether the PK of METH measured with a tracer dose of [11C]d-methamphetamine mimics the PK of a pharmacological dose that has behavioral effects. However, there is evidence that this is a valid assumption based on the fact the PK of [11C]dmethamphetamine in the baboon at tracer and at pharmacological doses did not differ (Fowler et al., 2007). For this study we also studied healthy, non-abusing controls rather than METH abusers. We felt that it was important to investigate these relationships in a control, non-abusing population to avoid introducing other variables such as the structural and neurochemical abnormalities (including long lasting decreases in DAT), which are known to occur in the METH abuser (Volkow et al., 2001b). We note that this study methodology could be adapted to the METH abuser after an adequate washout period to assure that the DAT availability measurement would not be influenced by METH occupancy of the DAT.

Another issue that needs to be addressed is the extent to which the C-11 in the brain reflects METH and not labeled metabolites or a combination of [11C]d-methamphetamine and its labeled metabolites. We analyzed the arterial plasma of each subject for the percent of the total C-11 that was in the form of the parent compound. We note that the appearance of labeled metabolites in plasma is slow so that input to the brain is mostly [11C]d-methamphetamine (Table 2). In addition, a major metabolite of METH is amphetamine, which arises from N-demethylation. Since [11C]d-methamphetamine is labeled in the N-methyl group, amphetamine would not be detected. Similarly, for [N-11C-methyl]cocaine, the only labeled molecule that can penetrate the brain is [11C]cocaine (Fowler et al., 1989).

In summary, in the first study of METH PK in the normal human brain, we found widespread and long-lasting distribution of METH, which parallels its long lasting behavioral effects. Widespread distribution of METH in brain is also consistent with reports that METH’s effects on brain chemistry and structure go beyond brain regions highly innervated with DA (i.e parietal cortex, white matter). Contrary to our original hypothesis, we found no difference in METH PK and bioavailability between Caucasians and African Americans suggesting that other variables need to be considered in accounting for the lower rate of METH abuse in African Americans. However, these comparative studies also revealed significant differences between Caucasians and African Americans in [11C]cocaine PK and bioavailability in brain which merit further investigation. Our finding that individuals with the highest striatal METH exposure also had the highest DAT availability suggests that DAT levels regulate the brain uptake of METH.

Acknowledgments

This research was carried out at Brookhaven National Laboratory under contract DE-AC02-98CH10886 with the U. S. Department of Energy and supported by its Office of Biological and Environmental Research and by NIH K05DA020001, the NIAAA Intramural program by GCRC grant #MO1RR10710. We are grateful to Richard Ferrieri and Michael Schueller for cyclotron and laboratory operations and to Anat Biegon for helpful discussions. We also thank the individuals who volunteered for these studies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alexoff DL, Shea C, Fowler JS, King P, Gatley SJ, Schlyer DJ, Wolf AP. Plasma input function determination for PET using a commercial laboratory robot. Nucl Med Biol. 1995;22:893–904. doi: 10.1016/0969-8051(95)00042-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balster RL, Schuster CR. Fixed-interval schedule of cocaine reinforcement: effect of dose and infusion duration. J Exp Anal Behav. 1973;20:119–129. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1973.20-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr AM, Panenka WJ, MacEwan GW, Thornton AE, Lang DJ, Honer WG, Lecomte T.The need for speed: an update on methamphetamine addiction J Psychiatry Neurosci 200631301–313. Review [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camp DM, Browman KE, Robinson TE. The effects of methamphetamine and cocaine on motor behavior and extracellular dopamine in the ventral striatum of Lewis versus Fischer 344 rats. Brain Res. 1994;668:180–193. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90523-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung A, Lyoo IK, Kim SJ, Hwang J, Bae SC, Sung YH, Sim ME, Song IC, Kim J, Chang KH, Renshaw PF. Decreased frontal white-matter integrity in abstinent methamphetamine abusers. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007;10:765–775. doi: 10.1017/S1461145706007395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook CE, Jeffcoat AR, Hill JM, Pugh DE, Patetta PK, Sadler BM, et al. Pharmacokinetics of methamphetamine self-administered to human subjects by smoking S-(+)-methamphetamine hydrochloride. Drug Metab Dispos. 1993;21:717–723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G, Imperato A. Drugs abused by humans preferentially increase synaptic dopamine concentrations in the mesolimbic system of freely moving rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:5274–5278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst T, Chang L, Leonido-Yee M, Speck O. Evidence for long-term neurotoxicity associated with methamphetamine abuse: A 1H MRS study. Neurology. 2000;54:1344–1349. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.6.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzmaurice PS, Tong J, Yazdanpanah M, Liu PP, Kalasinsky KS, Kish SJ. Levels of 4-hydroxynonenal and malondialdehyde are increased in brain of human chronic users of methamphetamine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;319:703–709. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.109173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Wolf AP, Dewey SL, Schlyer DJ, Macgregor RR, Hitzemann R, Logan J, Bendriem B, Gatley SJ, et al. Mapping cocaine binding sites in human and baboon brain in vivo. Synapse. 1989;4:371–377. doi: 10.1002/syn.890040412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler JS, Kroll C, Ferrieri R, Alexoff D, Logan J, Dewey SL, Schiffer W, Schlyer D, Carter P, King P, Shea C, Xu Y, Muench L, Benveniste H, Vaska P, Volkow ND. PET studies of d-methamphetamine pharmacokinetics in primates: comparison with l-methamphetamine and (-)-cocaine. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1724–1732. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.040279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima S, Shen H, Hata H, Ohara A, Ohmi K, Ikeda K, Numach i Y., Kobayashi H, Hall FS, Uhl GR, Sora I. Methamphetamine-induced locomotor activity and sensitization in dopamine transporter and vesicular monoamine transporter 2 double mutant mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;193:55–62. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0749-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fumagalli F, Gainetdinov RR, Valenzano KJ, Caron MG. Role of dopamine transporter in methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity: evidence from mice lacking the transporter. J Neurosci. 1998;18:4861–4869. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-13-04861.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fumagalli F, Gainetdinov RR, Wang YM, Valenzano KJ, Miller GW, Caron MG. Increased methamphetamine neurotoxicity in heterozygous vesicular monoamine transporter 2 knock-out mice. J Neurosci. 1999;19:2424–2431. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-07-02424.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue O, Axelsson S, Lundqvist H, Oreland L, Långström B. Effect of reserpine on the brain uptake of carbon 11 methamphetamine and its N-propargyl derivative, deprenyl. Eur J Nucl Med. 1990;17:121–126. doi: 10.1007/BF00811438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iritani BJ, Hallfors DD, Bauer DJ. Crystal methamphetamine use among young adults in the USA. Addiction. 2007;102:1102–1113. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalasinsky KS, Bosy TZ, Schmunk GA, Reiber G, Anthony RM, Furukawa Y, Guttman M, Kish SJ. Regional distribution of methamphetamine in autopsied brain of chronic human.methamphetamine users. Forensic Sci Int. 2001;116:163–169. doi: 10.1016/s0379-0738(00)00368-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczenski R, Everall IP, Crews L, Adame A, Grant I, Masliah E. Escalating dosemultiple binge methamphetamine exposure results in degeneration of the neocortex and limbic system in the rat. Exp Neurol. 2007;207:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan J, Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Wolf AP, Dewey SL, Schlyer DJ, MacGregor RR, Hitzemann R, Bendriem B, Gatley SJ, et al. Graphical analysis of reversible radioligand binding from time-activity measurements applied to [N-11C-methyl]-(-)-cocaine PET studies in human subjects. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1990;10:740–747. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1990.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton TF, Roache JD, De La Garza R, 2nd, Fong T, Wallace CL, Li SH, Elkashef A, Chiang N, Kahn R. Bupropion reduces methamphetamine-induced subjective effects and cue-induced craving. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:1537–1544. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil ML, Kuczenski R, Segal DS, Cho AK, Lacan G, Melega WP. Escalating dose pretreatment induces pharmacodynamic and not pharmacokinetic tolerance to a subsequent high-dose methamphetamine binge. Synapse. 2006;60:465–473. doi: 10.1002/syn.20320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawson RA, Condon TP. Why do we need an Addiction supplement focused on methamphetamine? Addiction. 2007;102(Suppl 1):1–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riviere GJ, Gentry WB, Owens SM. Disposition of methamphetamine and its metabolite amphetamine in brain and other tissues in rats after intravenous administration. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;292:1042–1047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman RB, Baumann MH, Dersch CM, Romero DV, Rice KC, Carroll FI, Partilla JS. Amphetamine-type central nervous system stimulants release norepinephrine more potently than they release dopamine and serotonin. Synapse. 2001;39:32–41. doi: 10.1002/1098-2396(20010101)39:1<32::AID-SYN5>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal DS, Kuczenski R, O’Neil ML, Melega WP, Cho AK. Prolonged exposure of rats to intravenous methamphetamine: behavioral and neurochemical characterization. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;180:501–512. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-2188-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sexton RL, Carlson RG, Siegal HA, Falck RS, Leukefeld C, Booth B. Barriers and pathways to diffusion of methamphetamine use among African Americans in the rural South: preliminary ethnographic findings. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2005;4:77–103. doi: 10.1300/J233v04n01_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Results from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings Office of Applied Studies, NHSDA Series H-22, DHHS Publication no. SMA 03–3836. 2003SAMHSA; Rockville, MD [Google Scholar]

- Thompson PM, Hayashi KM, Simon SL, Geaga JA, Hong MS, Sui Y, Lee JY, Toga AW, Ling W, London ED. Structural abnormalities in the brains of human subjects who use methamphetamine. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6028–6036. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0713-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Ding YS, Fowler JS, Wang GJ, Logan J, Gatley JS, Dewey S, Ashby C, Liebermann J, Hitzemann R, et al. Is methylphenidate like cocaine? Studies on their pharmacokinetics and distribution in the human brain. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:456–463. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950180042006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Logan J, Hitzemann R, Gatley SJ, MacGregor RR, Wolf AP. Cocaine uptake is decreased in the brain of detoxified cocaine abusers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;14:159–168. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(95)00073-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fischman MW, Foltin RW, Fowler JS, Abumrad NN, Vitkun S, Logan J, Gatley SJ, Pappas N, Hitzemann R, Shea CE. Relationship between subjective effects of cocaine and dopamine transporter occupancy. Nature. 1997;386:827–830. doi: 10.1038/386827a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fischman MW, Foltin R, Fowler JS, Franceschi D, Franceschi M, Logan J, Gatley SJ, Wong C, Ding YS, Hitzemann R, Pappas N. Effects of route of administration on cocaine induced dopamine transporter blockade in the human brain. Life Sci. 2000;67:1507–1515. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00731-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Chang L, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Franceschi D, Sedler MJ, Gatley SJ, Hitzemann R, Ding YS, Wong C, Logan J. Higher cortical and lower subcortical metabolism in detoxified methamphetamine abusers. Am J Psychiatry. 2001a;158:383–389. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Chang L, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Leonido-Yee M, Franceschi D, Sedler MJ, Gatley SJ, Hitzemann R, Ding YS, Logan J, Wong C, Miller EN. Association of dopamine transporter reduction with psychomotor impairment in methamphetamine abusers. Am J Psychiatry. 2001b;158:377–382. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volz TJ, Fleckenstein AE, Hanson GR.Methamphetamine-induced alterations in monoamine transport: implications for neurotoxicity, neuroprotection and treatment Addiction 2007102Suppl 144–48. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinshenker D, Ferrucci M, Busceti CL, Biagioni F, Lazzeri G, Liles LC, Lenzi P, Pasquali L, Murri L, Paparelli A, Fornai F.Genetic or pharmacological blockade of noradrenaline synthesis enhances the neurochemical, behavioral and toxic effects of methamphetamine J Neurochem 2007Dec 20 epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]