Abstract

This study addresses the causes and evolutionary consequences of introgressive hybridization in the sympatric species of Darwin's ground finches (Geospiza) on the small island of Daphne Major in the Galápagos archipelago. Hybridization occurs rarely (less than 2% of breeding pairs) but persistently across years, usually as a result of imprinting on the song of another species. Hybrids survive well under some ecological conditions, but not others. Hybrids mate according to song type. The resulting introgression increases phenotypic and genetic variation in the backcrossed populations. Effects of introgression on beak shape are determined by the underlying developmental genetic pathways. Introgressive hybridization has been widespread throughout the archipelago in the recent past, and may have been a persistent feature throughout the early history of the radiation, episodically affecting both the speed and direction of evolution. We discuss how fission through selection and fusion through introgression in contemporary Darwin's finch populations may be a reflection of processes occurring in other young radiations. We propose that introgression has the largest effect on the evolution of interbreeding species after they have diverged in morphology, but before the point is reached when genetic incompatibilities incur a severe fitness cost.

Keywords: adaptive radiation, allometry, imprinting, introgression, selection

1. Introduction

The process of speciation in nature is generally initiated by a change in environment, when exposure to new selective forces sets a population on a new evolutionary trajectory (Lewontin & Birch 1966; Grant & Grant 1989; Coyne & Orr 2004). In animals, behavioural modifications can sometimes ameliorate problems associated with ecological differences during an initial colonization event, or sudden environmental perturbation (Grant & Grant 2008), but for a successful response to altered conditions there must be enough genetic variation for the population to reach a new adaptive norm through natural selection. At any given time, the amount of standing genetic variation is a balance between opposing forces: gains through mutation and immigration and losses through genetic drift and oscillating selection as the population tracks ecological changes through time (Grant & Grant 2002). Introgressive hybridization is effective in increasing genetic variation because it simultaneously affects numerous genetic loci. The total effect on continuously varying traits can be up to two or three orders of magnitude greater than mutation (Grant & Grant 1994). Introgression can be particularly effective in small isolated populations, such as those found in archipelagos, or shortly after colonization of a new habitat by a few individuals, where genetic variation is likely to be eroded by selection, inbreeding and drift.

Botanists have long considered the process of interspecific gene transfer to be important in the evolutionary radiation of plants (Anderson 1948), but it was not until Lewontin & Birch's (1966) seminal paper on introgressive hybridization as a source of genetic variation for adaptation to new environments that it was considered to play a significant role in the early stages of animal radiations.

Lewontin & Birch's (1966) study organism, the Australian tephritid fly Dacus tryoni, had rapidly expanded its geographical range and became adapted to high temperatures over the previous 100 years. Since it had been observed to hybridize occasionally with Dacus neohumeralis in the wild (Gibbs 1968), introgression was considered to be a possible factor in this rapid change in physiology. Introgressive hybridization was investigated in laboratory experiments. The results supported the introgression hypothesis in showing that selection led to an increase in the introgressed population's ecological and physiological tolerances beyond the initial range of either of the parental species. Therefore, increased genetic variation as a result of introgression could have been responsible for the physiological changes observed in the wild. The importance of this work lies in the implication that a population can more rapidly respond to selection if its additive genetic variation is enhanced by introgressive hybridization than if it is genetically isolated (Lewontin & Birch 1966). Only recently has the general evolutionary significance of this finding become appreciated (Arnold 1997, 2006; Grant & Grant 2008).

At about the same time as Lewontin & Birch's (1966) experiments, a combined field and experimental study of coregonid fish in Sweden by Svärdson (1970) confirmed the variation-enhancing effects of introgression and demonstrated its potential role in the formation of new species. More recently, a number of studies have revealed the critical importance of interspecific gene transfer in species diversification. Examples are taxonomically widespread from prokaryotes, where lateral gene transfer has demonstrable evolutionary consequences (Ochman et al. 2000; Gogarten et al. 2002), to radiations of plants, crustaceans, corals, echinoderms, insects and primates (Byrne & Anderson 1994; Veron 1995; Wang & Szmidt 1995; Arnold 1997, 2006; Dowling & Secor 1997; Grant 1998; Seehausen 2004, 2006; Schmeller et al. 2005). These studies have revealed that gene flow between species is often unequal (Bacillieri et al. 1996; McDonald et al. 2001; Thulin & Tegelström 2002), tending to flow predominantly from common to rare species (Taylor & Hebert 1993; Wayne 1993; Dowling & Secor 1997); that incorporation of genes into the recipient's genome can be a selective process resulting in a mosaic composition of the genome (Martinsen et al. 2001; Rieseberg et al. 2003; Mallett 2005; Arnold 2006; Patterson et al. 2006); and that transgressive (extreme) phenotypes are not only a common feature of hybridization events (Rieseberg et al. 1999) but also under the appropriate novel environmental conditions they can be favoured by selection (Rieseberg et al. 2007).

Stebbins (1959) maintained that for major evolutionary advances to take place these genetically variable populations produced by introgression must be placed in an environment offering new ecological opportunities. Such locations are novel habitats typically at the periphery of species ranges (Stebbins 1959; Lewontin & Birch 1966; Rieseberg et al. 2003, 2007; Seehausen 2004), and they occur naturally for climatic and geological reasons (Rieseberg et al. 2007) or are produced by human-induced disturbance causing previously isolated species to be brought together (Cade 1983; Taylor et al. 2006). In short, hybridization raises the evolutionary potential of a population and ecological factors determine whether the outcome is fission, fusion or new directional change.

This paper describes a population study of Darwin's finches designed in part to elucidate the role of introgression in young adaptive radiations. They have several advantages. First, hybridization is known or suspected to occur among several species (Grant 1999). Second, finches are observable, parentage can be determined by genotyping and fitness can be quantified in small populations because the survival and reproductive fates of offspring can be documented. Third, fitness varies as a result of habitat change caused by extreme interannual climatic fluctuations. Finally, introgression between sympatric species occurs in situ in an entirely natural environment and is neither restricted to a hybrid zone as in many other taxa (Barton & Hewitt 1985; Harrison 1993; Barton 2001) nor to sister species.

Hybridization is an ecologically dependent behavioural phenomenon, with genetic consequences. Investigating the causes and evolutionary consequences of introgressive hybridization in the wild thus requires answering a number of questions. Why do some individuals hybridize and others do not? How fit are the hybrids relative to the parental species? By how much does introgression increase genetic and phenotypic variation of a population? What are the genetic underpinnings of the traits that allow flexibility in the development of a new morphology? Was introgressive hybridization a persistent feature in the past, with occasional but important effects on the speed and direction of evolution, or is it a short-term transient phenomenon with little evolutionary significance? We attempt to answer these questions with the results of a study of finch populations over several generations at times of ecological change: with data on the morphology, genetics, behaviour and feeding ecology of marked individuals.

We first briefly describe the island setting and the finches, then the profound interannual fluctuations in rainfall and the effect this has on the finches and their environment, before addressing the above questions. We conclude by considering the implications of our findings for other young radiations in different taxonomic groups.

2. Environments, finches and natural selection

Daphne Major is a small island, approximately 34 ha in area, near the centre of the Galápagos archipelago. It is a tuff (volcanic) cone with a large central crater. Four species of ground finches breed on the island. Geospiza fortis (approx. 17 g), the medium ground finch, is a granivorous bird with a short and blunt beak; Geospiza scandens (approx. 21 g), the cactus finch, which, as its name implies, feeds on Opuntia cactus seeds, pollen and nectar in the dry season, has a long-pointed beak; Geospiza magnirostris (approx. 30 g), the large-beaked ground finch, feeds on large and hard seeds; and Geospiza fuliginosa (approx. 12 g), the small ground finch, feeds on small seeds. Depending on environmental conditions, the population of G. fortis ranges from well over 1500 to less than 100 individuals, whereas the G. scandens population ranges from approximately 600 to less than 60 individuals. G. magnirostris established a breeding population on Daphne in 1982–1983 and its numbers gradually increased to a maximum of approximately 350 in 2003 (Grant & Grant 2006). G. fuliginosa is a frequent but rare immigrant that occasionally breeds on the island.

The climate is seasonal, with a hot, wet season extending from January to May followed by a cooler, drier season from June to December. Rainfall varies interannually as a result of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) phenomenon. El Niño events occur unpredictably on average twice a decade. They bring large quantities of rain to the islands and are interspersed among years of little or no rainfall. Birds typically begin breeding one to two weeks after the first heavy rains of the year; in years with no rain, no breeding occurs (Grant & Grant 1989; Grant 1999).

Conditions for the finches during severe droughts depend on the types and quantities of seeds in the seed bank, which in turn depend on preceding conditions. For example, in the drought of 1977, when approximately 85% of G. fortis died, the seed bank was principally made up of large and hard seeds that had been produced by the predominant flowering plant (Tribulus cistoides) during the preceding years of relatively low rainfall. Only G. fortis individuals with large beaks strong enough to crack Tribulus seeds survived; the smaller members of that population died as the small soft seeds were rapidly depleted over the year (Boag & Grant 1981). By contrast, the drought of 1985 followed the longest and most severe El Niño event of 400 years, as estimated from coral cores (Glynn 1990). The extraordinary El Niño event in 1982–1983 completely altered the ecology of the islands, changing it from a large and hard seed environment dominated by Tribulus and Opuntia seeds to one dominated by the small and soft seeds produced in combination by 24 species of grass and herbs. Vines smothered the low-growing Tribulus plants and Opuntia bushes. Under these altered conditions in 1985, small pointed-beaked G. fortis survived disproportionately well (Gibbs & Grant 1987). Beak size is highly heritable, as shown by a regression of mid-offspring on mid-parent values (Grant & Grant 2000; Keller et al. 2001). As a result, in the breeding seasons following drought years the surviving adults produced young of similar beak size and shape to themselves.

Over the next 20 years, ecological conditions oscillated in direction. Evolutionary responses to natural selection on beak size and shape tracked these oscillations (Grant & Grant 2002). Interestingly, after 30 years the mean beak dimensions of the finch populations had not returned to the 1973 starting point of the study, but instead beaks of G. fortis were more pointed on average, and beaks of G. scandens were smaller and blunter in 2002 than in 1973 (Grant & Grant 2002). The two populations had converged morphologically over this period.

These results demonstrate that populations track environmental changes through evolutionary responses to oscillating directional natural selection. Evolutionary changes are measurable, interpretable and occur over a short period of time. They raise three questions. First, why did the species converge? Second, where did the genetic variation come from to fuel the repeated process of evolutionary change, when oscillating selection continuously erodes it? The answer to both questions is introgressive hybridization. Before discussing the role of hybridization we address a third question: in light of their morphological convergence, what keeps the species apart and prevents them from fusing into a single panmictic population?

3. Barriers to interbreeding

All species of Darwin's ground finches are similar in the type of nest they build, their courtship behaviour and their plumage, males being black and females brown (Lack 1947). Species differ conspicuously in song, body size, and beak size and shape, and it is these features that we suspected were being used by the birds to discriminate between members of their own and different species. Field experiments using playback of song in the absence of any morphological cues demonstrated that individuals clearly discriminate between their own and other species on the basis of song alone (Ratcliffe & Grant 1983). Similarly, presentation of museum specimens in the absence of any vocal cues showed that individuals readily discriminate between conspecifics and heterospecifics on the basis of morphology alone (Lack 1947; Ratcliffe & Grant 1983, 1985). Thus, differences in both song and morphology can act as pre-mating barriers to interbreeding (Grant et al. 1996; Grant & Grant 1996a, 1997a,b, 2008).

Song differences are especially important. Males of both species sing a single short song, whereas females do not sing. Although species songs are discretely different, there is individual variation in motifs within a species' song. Bowman (1983) showed with laboratory-reared birds that song is learned during a short sensitive period early in life in an imprinting-like process. The sensitive period occurs from day 10 to day 40 after hatching, which coincides with the last few days in the nest and the time of parental dependency as fledglings. As a result, detailed features of song are transmitted from father to son in three quarters of the males, and are acquired from other males in the remainder. Finches can live for up to 16 years, and spectrograms of annual recordings show that a song once learned remains unaltered for life (Grant & Grant 1996a, 1998). Therefore, unlike beak size and shape, which are genetically inherited, song is learned and culturally transmitted. The visual cues of beak size and shape are presumably learned in association with song during the sensitive period early in life, by females as well as males.

4. Hybridization

The barrier to interbreeding set up by morphological and song differences is not impermeable but leaks. Imprinting is vulnerable to disruption if a young bird hears the song of another species during its sensitive period early in life. This happened rarely but consistently across all years of our study, and occurs for idiosyncratic reasons. It can occur when an individual of one species takes over the nest of another species and an egg is left behind: after hatching, the chick learns its foster father's song. Disruption can occur when the father dies or when different species nest close together and one male dominates the singing space of both nests. Such misimprinted G. fortis and G. scandens usually breed according to song type but not morphology and thus hybridize (Grant & Grant 1996a, 1998).

When species are very different in size they do not interbreed. A total of six G. fortis males have misimprinted on G. magnirostris songs, but none have paired with a G. magnirostris female (Grant & Grant 2008), in spite of being more closely related to them than they are to G. scandens (Petren et al. 1999; Sato et al. 1999). Whereas the mean size difference between G. fortis and G. scandens is 4 g, it is 12 g between G. fortis and G. magnirostris on Daphne. On Santa Cruz island where G. fortis is much larger, interbreeding with G. magnirostris does occur (Huber et al. 2007).

Our observations suggest that harassment is another reason why interbreeding does not occur on Daphne. All six G. fortis males singing G. magnirostris songs were harassed repeatedly by territorial G. magnirostris as soon as they sang. Only one obtained a mate and he did so after 7 years. He became almost completely silent and then paired not with a G. magnirostris female but with a G. fortis female. In this case, pair formation was based on morphology and not on song (Grant & Grant 2008).

5. Hybrid fitness and introgression

Hybrids survive under some ecological conditions but not others. From 1976 to 1983, large and hard Tribulus and Opuntia seeds dominated the seed bank, and under these conditions no hybrid survived the dry season to breed. Hybrids are intermediate in morphology between the two parental species owing to the high heritability of body size and beak dimensions (Grant & Grant 2000). With beaks of generally intermediate size hybrids can feed on small soft seeds but are unable to crack the large and hard seeds of T. cistoides, even though they occasionally try. They take up to three times longer to crack an Opuntia cactus seed than G. scandens does (Grant & Grant 1996b). After the El Niño event of 1982–1983 small seeds became plentiful; hybrids with intermediate beaks capable of dealing with small soft seeds survived, and with a continuing supply of these seeds they survived well over the following 20 years.

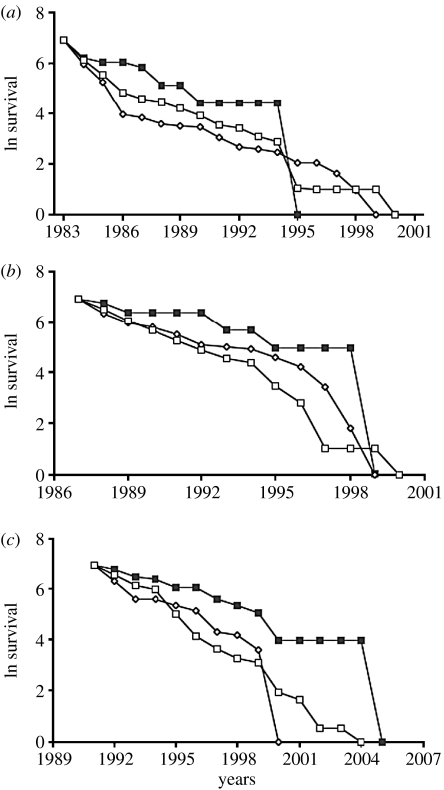

To examine how well the hybrids survived in comparison with the pure species hatched at the same time and living under the same conditions, we followed the survival of the first three large cohorts produced in the years of abundant rainfall (1983, 1987 and 1991). In each cohort, hybrids and backcrosses survived as good as, or even better than, pure G. fortis and G. scandens (figure 1). Furthermore, there was no significant difference in egg production, hatching success or fledgling survival between hybrids, backcrosses and pure species (Grant & Grant 1992, 1996a, 1998), and thus no indication of genetic incompatibilities between the species.

Figure 1.

Survival on a natural log scale of three cohorts (a, 1983; b, 1987; c, 1991) of hybrids and backcrosses (H; solid squares) in relation to the parental species, G. fortis (F; open circles) and G. scandens (S; open squares), over their lifetime on Daphne Major Island. Initial sample sizes are: (a) F=1019, S=553, H=12; (b) F=955, S=164, H=7; (c) F=581, S=108, H=19. Adapted from Grant & Grant (2008).

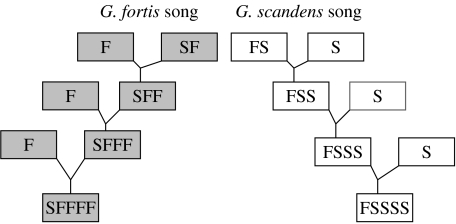

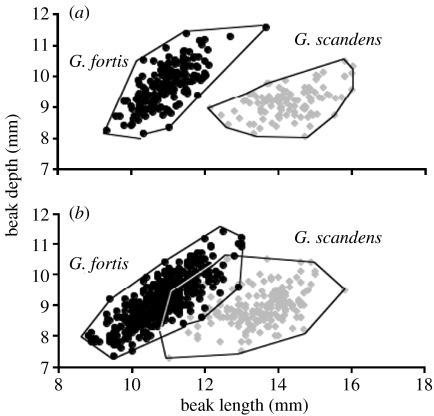

Hybrids, being always rare, have never mated with each other. Instead, they backcross to one or other of the parental species according to their father's song type and not, usually, according to morphology (figure 2). They appear to be at no disadvantage in gaining mates (Grant & Grant 1997a,b). Altogether, this has resulted in an exchange of alleles between the species (Grant & Grant 1996a, 1998; Grant et al. 2004). Hybrid production has remained rare but constant throughout the study. Gene exchange, although bidirectional, was three times greater from G. fortis to G. scandens than in the opposite direction, possibly associated with an unequal sex ratio among G. scandens breeders (Grant & Grant 2002). Thus, the G. scandens population shows the greatest increase in morphological and genetic variation (Grant & Grant 2002; Grant et al. 2004). Despite the low production of hybrids, by 2007, over 30% of the population of G. scandens possessed alleles whose origin could be traced back to G. fortis. The two populations had become more similar to each other morphologically and genetically (figure 3) but were held apart by song, a learned, culturally transmitted trait (Grant et al. 2004).

Figure 2.

Mating patterns of hybrids and backcrosses. Both sons and daughters imprint on their father's song and mate according to species song type. Hybrids do not sing intermediate songs. As a result of introgressive hybridization genes flow from one species to another, but the two populations are kept apart by song. FS refers to a hybrid, the product of a G. fortis father imprinted on a G. scandens song mated to a G. scandens female. FSS refers to a first-generation backcross, FSSS refers to a second-generation backcross, etc. Adapted from Grant & Grant (2008).

Figure 3.

Morphological convergence on Daphne Major Island as a result of introgressive hybridization. Polygons enclose members of each population identified by song (males) or the song of mates (females). (a) 1978–1982 and (b) 1990–2003.

6. Reinforcement and character displacement

Dobzhansky (1937, 1941) proposed that when hybrid viability is weak the barrier to interbreeding would be reinforced as a result of selection. Any factor contributing to the prevention of mating between species would be at a selective advantage, and would increase in frequency in a manner dependent upon the relative fitness of the hybrids, as determined by their survival and reproductive success (Liou & Price 1994; Hostert 1997). Evidence for reinforcement and the divergence of traits involved in mate choice (character displacement) is taxonomically widespread (Sætre et al. 1997; Marshall & Cooley 2000; Pfennig 2003; Coyne & Orr 2004; Peterson et al. 2005). Reproductive isolation in Darwin's finches appears to be entirely prezygotic as there is no evidence of genetic incompatibilities (Grant 1999). Nevertheless, selection could operate at the time of ecological disadvantage for the hybrids. An intriguing possibility is that song differences between sympatric species could be reinforced at this time, although we have no evidence for it.

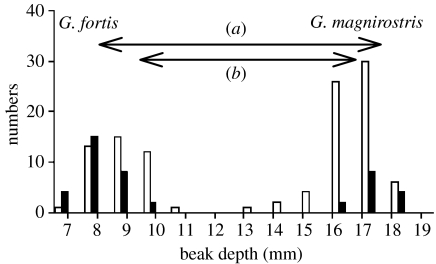

Ecological character displacement, which is the enhancement of differences between sympatric species by natural selection, usually as a result of competition, can indirectly reinforce the difference in mating signals between species. Character displacement occurred on Daphne during a severe drought in 2004–2005 (figure 4). The population of G. magnirostris depleted the seed supply of Tribulus seeds, normally consumed by large-beaked G. fortis individuals. Over 90% of the G. fortis population died, leaving only relatively small birds that were capable of surviving on a diet of small seeds. The consequence was an evolutionary shift to a significantly smaller mean beak size in the next generation produced the following year (Grant & Grant 2006). This provides an example of how a barrier to interbreeding can be strengthened in the non-breeding season as a result of ecological factors, even though in this case the barrier was effective even before character displacement occurred.

Figure 4.

Character displacement on Daphne Major Island as a result of differential survival during the drought of 2003–2004. White bars are non-survivors and black bars are survivors. The species differed more in mean beak depth (a) after the drought than (b) before the drought.

7. Changes in beak shape

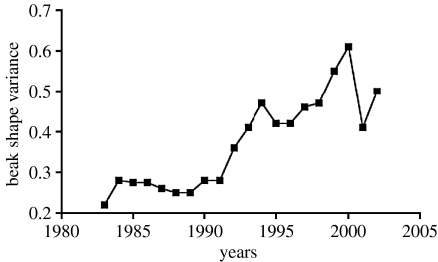

Evolutionary change in proportions is constrained to some extent by genetic variances of traits and genetic correlations between them (Schluter 1996; Seehausen 2004, 2006; Brakefield 2006; Herder et al. 2006). Introgression has the potential to increase the standing additive genetic variation governing traits and their phenotypic variation (figure 5), thereby allowing the population to more rapidly respond to selection. We estimated that introgression increased the additive genetic variance in six measured traits in G. fortis by 36–73% (mean 54.9) and in G. scandens by 2–69% (mean 32.2; Grant & Grant 1994). It may also facilitate evolution of the population along a novel trajectory by relaxing the genetic constraints imposed by correlations between traits such as beak length and depth (Grant & Grant 1994). Whether it does so or not depends, in part, on the magnitude of the genetic correlations and on their allometric relations. For example, the genetic correlation between beak width or depth and length is strong in G. fuliginosa, G. fortis and G. magnirostris, whereas it is weaker in G. scandens. Introgressive hybridization between species with different allometries such as G. fortis and G. scandens tends to weaken genetic correlations, thus potentially facilitating a change in shape that is relatively unconstrained genetically. On the other hand, when the interbreeding species have similar allometries, as in the case of G. fuliginosa and G. fortis, genetic correlations are strengthened as a result of gene exchange and change in shape is more tightly constrained (Grant & Grant 1994). The relative ease of size changes, compared with shape changes, may account for the small, medium and large forms that we see in both tree and ground finches, and frequently in other congeneric species of birds on continents as well as archipelagos (Price 2007).

Figure 5.

Increase in beak shape variance in G. scandens on Daphne Major Island as a result of introgressive hybridization with G. fortis. Adapted from Grant et al. (2004).

Recent collaboration with Arkhat Abzhanov and Cliff Tabin on the genetics of beak development has thrown light on the underlying genetic reasons for the above patterns (Abzhanov et al. 2004, 2006). At day 6 in the developing finch embryo the expression of a growth factor, bone morphogenetic protein 4 (Bmp4), in the mesenchyme of upper beaks is associated with the development of a deep and broad adult beak. At this stage, Bmp4 is expressed in increasing amounts and over a larger domain in the sequence G. fuliginosa to G. fortis to G. magnirostris. At the same time, a calmodulin-dependent signalling pathway is involved in the development of beak length. The long and pointed-beaked G. scandens embryos strongly express calmodulin (CaM), but not Bmp4. Thus, Bmp4- and CaM-dependent signalling pathways are involved in growth along different beak axes (width or depth and length, respectively), and they do so independently and not antagonistically, thereby allowing the evolution of different beak shapes (Abzhanov et al. 2004, 2006). On the other hand, beak depth and width are more tightly constrained by the control of a single molecule, Bmp4.

8. Hybridization in the recent past

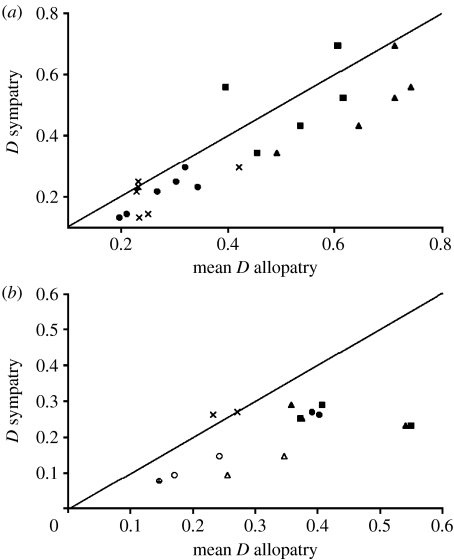

To determine whether introgressive hybridization has been a persistent feature throughout the history of the Darwin's finch radiation, we looked for indications of introgression on other islands in the recent past, by comparing allopatric and sympatric pairs of closely related species at 16 microsatellite loci that are presumed to be selectively neutral (Grant et al. 2005). Although sympatric species are morphologically distinct, we reasoned that if hybridization between closely related sympatric species has been a widespread phenomenon, two closely related species, call them A and B, should be more similar genetically to each other on the same island than either of them on that island (e.g. A) is to the other (B) on another island. In both ground and tree finches, we indeed found that closely related species were more similar to each other in sympatry than each species was to the other in allopatry (figure 6). Introgressive hybridization appears to have been occurring widely throughout the archipelago (Grant et al. 2005), and is perhaps continuing on several islands.

Figure 6.

Hybridization in the recent past is indicated by the greater genetic similarity of sympatric populations of species than allopatric populations of the same species. Different symbols indicate different combinations of species of (a) ground finches (Geospiza spp.) and (b) tree finches (Camarhynchus spp.) From Grant et al. (2005). D indicates genetic distance.

9. Conclusions & discussion

Three factors contribute to the barrier for interbreeding and an exchange of genes between Darwin's finch species: differences in song, morphology and ecological conditions during the dry season. The barrier breaks down with a simultaneous weakening of the differences. They hybridize when individuals learn the song of another species and morphological differences between them are small. When ecological conditions are suitable for the survival of F1 hybrids they backcross to the parental species. A long-term field study on Galápagos shows that such ecological conditions occur episodically.

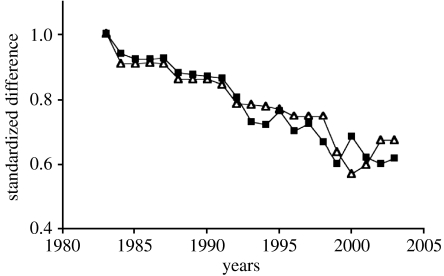

The footprint of hybridization in the recent past elsewhere in the archipelago encourages us to think that the results of observing finches closely on the small island of Daphne for 35 years are generalizable to some degree. Similar to Lewontin & Birch (1966) and Svärdson (1970), we found that introgression had an enhancing effect on additive genetic variation. At different times hybrids have had relatively high or low fitness. Putting these results together with the repeated observation of natural selection, oscillating in direction, we suggest that episodic introgressive hybridization between relatively young species can be viewed profitably in a fission–fusion framework. Young species can fuse into one through hybridization; figure 7 illustrates this trajectory. Alternatively they may split apart through selection against intermediates; figure 4 helps to visualize this process. The alternative endpoints may take a long time to reach as the interbreeding populations, subject to fluctuations in environmental conditions, oscillate between fusion and fission tendencies (Grant & Grant 1997c, 2008).

Figure 7.

Morphological and genetic convergence of G. fortis and G. scandens on Daphne Major Island. Standardization was achieved by giving a value of 1.0 to the difference between the species, in 1982, in beak shape and in Nei's D calculated from alleles at 16 microsatellite loci. Adapted from Grant et al. (2004). Squares, genetic distance; triangles, beak shape.

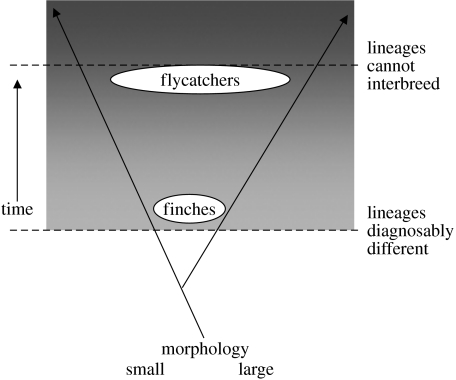

The natural occurrence of introgressive hybridization is analogous to the process used by animal breeders, as discussed by Darwin (1868), to obtain new combinations of favoured traits by crossing lineages after a period of independent selection. In nature it occurs mainly between young species (figure 8), and is evident in several young adaptive radiations including those of butterflies (Mallett 2005), cichlid fish (Kocher 2004; Seehausen 2006) and primates (Arnold 2006; Patterson et al. 2006). With the lapse of time introgression declines, for two reasons: species diverge in morphological and behavioural traits and no longer recognize each other as potential mates (pre-mating isolation), and they diverge genetically with the result that if they interbreed their offspring are relatively inviable or infertile (post-mating isolation). Figure 8 illustrates the early and late stages of divergence, which contrasts the relatively unimpeded introgression in Darwin's finches with partial sterility-limited introgression in Ficedula flycatchers in Scandinavia (Sætre et al. 2001).

Figure 8.

Schematic of speciation. Two populations diverge and eventually reach a stage at which they are incapable of exchanging genes. Darwin's finches are at an early stage in this process and Ficedula flycatchers are at a late stage.

Divergence and a decline in introgression with time implies that introgression has the largest evolutionary effect after some morphological, ecological and genetic differences between species have arisen, but before the point is reached when genetic incompatibilities incur a severe fitness cost (Grant et al. 2004; Grant & Grant 2008). As a corollary, if species that diverge in allopatry do not encounter each other until after this stage has been reached, perhaps in large continental areas or at times of climatic stability, their evolutionary dynamics will not be affected by introgression. Hence, adaptive radiations, which are driven by strong selective pressures and introgressive hybridization, may be dependent upon frequent opportunities for differentiated populations to establish sympatry. This means that they are more likely to occur in spatially confined environments than in large expansive ones.

A second, less obvious and more speculative implication of the proposed decline in introgression is that species are more likely to become extinct when they cease to interbreed. They might do so because they have to respond to the challenge of environmental change in the absence of an augmented supply of genetic variation from introgression. Extinction of relatives is one possible factor contributing to the explanation for why older species differ from each other in morphology and ecology to a pronounced degree. The other reason is they have had a long time to diverge through natural selection and random drift. The pattern is illustrated by the four oldest living species at the base of the Darwin's finch radiation; warbler finch (Certhidea), Pinaroloxias (Cocos Island finch), the sharp-beaked ground finch (G. difficilis) and vegetarian finch (Platyspiza). They are so distinct from each other that they span the entire morphological space of the present day radiation (Grant & Grant 2008). Unlike the more recently derived species they are not known to hybridize (Grant 1999).

The same pattern of morphological disparity and ecological diversity at the base of the phylogeny has been noted as a common trend in other radiations (e.g. Lovette & Bermingham 1999; Harmon et al. 2003; Seehausen 2006). Fission–fusion dynamics were probably played out in the early stages of these radiations, as indicated by frequent hybridization in the newer species, but being a transient stage in the radiation they have left no record in older species apart from faint echoes in their genomes (Patterson et al. 2006; Linnen & Farrell 2007; Peters et al. 2007). A challenge for the future is to refine methods of inferring the effects of introgression in the past and to take advantage of the rapidly increasing amounts of available genomic data. Complementary field studies of current hybridization are needed to interpret the causes and consequences of hybridization in the past.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Galápagos National Parks Service and Charles Darwin Research Station for permission to carry out the fieldwork and for logistical support. We thank Nora Brede and Klaus Schwenk for the invitation to the stimulating symposium on hybridization, and the many field assistants over the years who helped to make this work possible. The research has been supported by grants from the National Science and Environmental Research Council (Canada) and the National Science Foundation (USA).

Footnotes

One contribution of 16 to a Theme Issue ‘Hybridization in animals: extent, processes and evolutionary impact’.

References

- Abzhanov A, Protas M, Grant P.R, Grant B.R, Tabin C.J. Bmp4 and morphological variation of beaks in Darwin's finches. Science. 2004;305:1462–1465. doi: 10.1126/science.1098095. doi:10.1126/science.1098095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abzhanov A, Kuo W.P, Hartmann C, Grant B.R, Grant P.R, Tabin C.J. The calmodulin pathway and evolution of elongated beak morphology in Darwin's finches. Nature. 2006;442:563–567. doi: 10.1038/nature04843. doi:10.1038/nature04843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E. Hybridization of the habitat. Evolution. 1948;2:1–9. doi:10.2307/2405610 [Google Scholar]

- Arnold M.L. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 1997. Natural hybridization and evolution. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold M.L. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2006. Evolution through genetic exchange. [Google Scholar]

- Bacillieri R, Ducousso A, Petit R.J, Kremer A. Mating system and asymmetric hybridization in a mixed stand of oaks. Evolution. 1996;50:900–908. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1996.tb03898.x. doi:10.2307/2410861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton N.H. The role of hybridization in evolution. Mol. Ecol. 2001;10:551–568. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2001.01216.x. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294x.2001.01216.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton N.H, Hewitt G.M. Adaptation, speciation, and hybrid zones. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1985;16:113–148. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.16.110185.000553 [Google Scholar]

- Boag P.T, Grant P.R. Intense natural selection in a population of Darwin's finches (Geospizinae) in the Galápagos. Science. 1981;214:82–85. doi: 10.1126/science.214.4516.82. doi:10.1126/science.214.4516.82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman R.I. The evolution of song in Darwin's Finches. In: Bowman R.I, Berson M, Leviton A.E, editors. Patterns of evolution in Galápagos organisms. American Association for the Advancement of Science; Pacific Division, CA: 1983. pp. 237–537. [Google Scholar]

- Brakefield P.M. Evo-devo and constraints on selection. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2006;21:362–368. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2006.05.001. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2006.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne M, Anderson M.J. Hybridization of sympatric Patiriella species (Echinodermata: Asteroidea) in New South Wales. Evolution. 1994;48:564–576. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1994.tb01344.x. doi:10.2307/2410469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cade T.J. Hybridization and gene exchange among birds in relation to conservation. In: Schonewald-Cox C.M, MacBryde B, Thomas W.L, editors. Genetics and conservation. Benjamin/Cummings; Menlo Park, CA: 1983. pp. 288–309. [Google Scholar]

- Coyne J.A, Orr A.R. Sinauer; Sunderland, MA: 2004. Speciation. [Google Scholar]

- Darwin C. J. Murray; London, UK: 1868. The variation of animals and plants under domestication. [Google Scholar]

- Dobzhansky T. Columbia University Press; New York, NY: 1937. Genetics and the origin of species. [Google Scholar]

- Dobzhansky T. 2nd edn. Columbia University Press; New York, NY: 1941. Genetics and the origin of species. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling T.E, Secor C.L. The role of hybridization and introgression in the diversification of animals. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1997;12:23–48. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs G.W. The frequency of interbreeding between two sibling species of Dacus (Diptera) in wild populations. Evolution. 1968;22:667–683. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1968.tb03469.x. doi:10.2307/2406895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs H.L, Grant P.R. Oscillating selection on Darwin's finches. Nature. 1987;327:511–513. doi:10.1038/327511a0 [Google Scholar]

- Glynn P.W. Elsevier; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 1990. Global ecological consequences of the 1982–83 El Niño-Southern Oscillation. [Google Scholar]

- Gogarten J.P, Doolittle W.F, Lawrence J.G. Prokaryotic evolution in light of gene transfer. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2002;19:2226–2238. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant P.R. Speciation. In: Grant P.R, editor. Evolution on islands. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 1998. pp. 83–101. [Google Scholar]

- Grant P.R. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 1999. Ecology and evolution of Darwin's finches. [Google Scholar]

- Grant B.R, Grant P.R. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 1989. Evolutionary dynamics of a natural population: the large cactus finch of the Galápagos. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant B.R, Grant P.R. Cultural inheritance of song and its role in the evolution of Darwin's finches. Evolution. 1996a;50:2471–2487. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1996.tb03633.x. doi:10.2307/2410714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant B.R, Grant P.R. High survival of Darwin's finch hybrids: effects of beak morphology and diets. Ecology. 1996b;77:500–509. doi:10.2307/2265625 [Google Scholar]

- Grant B.R, Grant P.R. Hybridization and speciation in Darwin's finches: the role of sexual imprinting on a culturally transmitted trait. In: Howard D.J, Berlocher S.H, editors. Endless forms: species and speciation. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 1998. pp. 404–422. [Google Scholar]

- Grant P.R, Grant B.R. Hybridization of bird species. Science. 1992;256:193–197. doi: 10.1126/science.256.5054.193. doi:10.1126/science.256.5054.193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant P.R, Grant B.R. Phenotypic and genetic effects of hybridization in Darwin's finches. Evolution. 1994;48:297–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1994.tb01313.x. doi:10.2307/2410094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant P.R, Grant B.R. Hybridization, sexual imprinting, and mate choice. Am. Nat. 1997a;149:1–28. doi:10.1086/285976 [Google Scholar]

- Grant P.R, Grant B.R. Mating patterns of Darwin's finch hybrids determined by song and morphology. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 1997b;60:317–343. [Google Scholar]

- Grant P.R, Grant B.R. Genetics and the origin of bird species. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1997c;94:7768–7775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.7768. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.15.7768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant P.R, Grant B.R. Quantitative genetic variation in populations of Darwin's finches. In: Mousseau T.A, Sinervo B, Endler J, editors. Adaptive variation in the wild. Academic Press; New York, NY: 2000. pp. 3–40. [Google Scholar]

- Grant P.R, Grant B.R. Unpredictable evolution in a 30-year study of Darwin's finches. Science. 2002;296:707–711. doi: 10.1126/science.1070315. doi:10.1126/science.1070315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant P.R, Grant B.R. Evolution of character displacement in Darwin's Finches. Science. 2006;313:224–226. doi: 10.1126/science.1128374. doi:10.1126/science.1128374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant P.R, Grant B.R. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 2008. How and why species multiply: the radiation of Darwin's Finches. [Google Scholar]

- Grant P.R, Grant B.R, Deutsch J.C. Speciation and hybridization of island birds. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 1996;351:765–772. doi:10.1098/rstb.1996.0071 [Google Scholar]

- Grant P.R, Grant B.R, Markert J.A, Keller L.F, Petren K. Convergent evolution of Darwin's finches caused by introgressive hybridization and selection. Evolution. 2004;58:1588–1599. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2004.tb01738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant P.R, Grant B.R, Petren K. Hybridization in the recent past. Am. Nat. 2005;166:56–67. doi: 10.1086/430331. doi:10.1086/430331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmon L.J, Schultte J.A, II, Larson A, Losos J. Tempo and mode of evolutionary radiation in iguanian lizards. Science. 2003;301:961–964. doi: 10.1126/science.1084786. doi:10.1126/science.1084786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison R.G, editor. Hybrid zones and the evolutionary process. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Herder F, Nolte A.W, Pfaender J, Schwarzer J, Hadiaty R.K, Schliewen U.K. Adaptive radiation and hybridization in Wallace's Dreamponds: evidence from sailfin silversides in the Malili Lakes of Sulawesi. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2006;273:2209–2217. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3558. doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.3558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hostert E.E. Reinforcement: a new perspective on an old controversy. Evolution. 1997;51:697–702. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1997.tb03653.x. doi:10.2307/2411146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber S.K, De Léon L.F, Hendry A.P, Bermingham E, Podos J. Reproductive isolation of sympatric morphs in a population of Darwin's finches. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2007;274:1709–1724. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.0224. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.0224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller L.F, Grant P.R, Grant B.R, Petren K. Heritability of morphological traits in Darwin's finches: misidentified paternity and maternal effects. Heredity. 2001;87:325–336. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2540.2001.00900.x. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2540.2001.00900.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocher T.D. Adaptive evolution and explosive speciation: the cichlid fish model. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2004;5:288–298. doi: 10.1038/nrg1316. doi:10.1038/nrg1316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lack D. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 1947. Darwin's finches. [Google Scholar]

- Lewontin R.C, Birch L.C. Hybridization as a source of variation for adaptation to new environments. Evolution. 1966;20:315–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1966.tb03369.x. doi:10.2307/2406633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnen C.R, Farrell B.D. Mitonuclear discordance is caused by rampant mitochondrial introgression in Neodiprion (Hymenoptera: Diprionidae) sawflies. Evolution. 2007;61:1417–1438. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00114.x. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00114.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou L.W, Price T.D. Speciation by reinforcement of premating isolation. Evolution. 1994;48:1451–1459. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1994.tb02187.x. doi:10.2307/2410239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovette I.J, Bermingham E. Explosive speciation in the New World Dendroica warblers. Proc. R. Soc. B. 1999;266:1629–1636. doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0825 [Google Scholar]

- Mallett J. Hybridization as an invasion of the genome. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2005;20:229–237. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2005.02.010. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2005.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall D.C, Cooley J.R. Reproductive character displacement and speciation in periodical cicadas, with a description of a new species, 13-year Magicicada neotredecim. Evolution. 2000;54:1313–1325. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb00564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinsen G.D, Whitham T.G, Turek R.J, Keim P. Hybrid populations selectively filter gene introgression between species. Evolution. 2001;55:1325–1335. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2001.tb00655.x. doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2001.tb00655.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald D.B, Clay R.P, Brumfield R.T, Braun M.J. Sexual selection on plumage and behavior in an avian hybrid zone: experimental tests of male–male interactions. Evolution. 2001;55:1443–1451. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2001.tb00664.x. doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2001.tb00664.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochman H, Lawrence J.G, Groisman E.A. Lateral gene transfer and the nature of bacterial innovation. Nature. 2000;405:299–304. doi: 10.1038/35012500. doi:10.1038/35012500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson N, Richter D.J, Gnerre S, Lander E.S, Reich D. Genetic evidence for complex speciation of humans and chimpanzees. Nature. 2006;441:1103–1108. doi: 10.1038/nature04789. doi:10.1038/nature04789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J.L, Zhuravlev Y, Fefelov I, Logie A, Omland K.E. Nuclear loci and coalescent methods support ancient hybridization as cause of mitochondrial paraphyly between gadwall and falcated duck (Anas spp.) Evolution. 2007;61:1992–2006. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00149.x. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00149.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson M.A, Honchak B.A, Locke S.E, Beeman T.E, Mendoza J, Green J, Buckingham K.J, White M.A, Monsen K.J. Relative abundance and the species-specific reinforcement of male mating preference in the Chrysochus (Coleoptera: Chysomelidae) hybrid zone. Evolution. 2005;59:2639–2655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petren K, Grant B.R, Grant P.R. A phylogeny of Darwin's finches based on microsatellite DNA length variation. Proc. R. Soc. B. 1999;266:321–329. doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0641 [Google Scholar]

- Pfennig K. A test of alternative hypotheses for the evolution of reproductive isolation between spadefoot toads: support for the reinforcement hypothesis. Evolution. 2003;57:2842–2851. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb01525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price T.D. Roberts & Co; Greenwood Village, CO: 2007. Speciation in birds. [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe L.M, Grant P.R. Species recognition in Darwin's Finches (Geospiza, Gould). I. Discrimination by morphological cues. Anim. Behav. 1983;31:1139–1153. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(83)80021-9 [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe L.M, Grant P.R. Species recognition in Darwin's Finches (Geospiza, Gould). III. Male responses to playback of different song types, dialects and heterospecific songs. Anim. Behav. 1985;33:290–307. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(85)80143-3 [Google Scholar]

- Rieseberg L.H, Archer M.A, Wayne R.K. Transgressive segregation, adaptation and speciation. Heredity. 1999;4:363–372. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6886170. doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6886170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieseberg L.H, et al. Major ecological transitions in wild sunflowers facilitated by hybridization. Science. 2003;301:1211–1216. doi: 10.1126/science.1086949. doi:10.1126/science.1086949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieseberg L.H, Kim S.-C, Randell R.A, Whitney K.D, Gross B.L, Lexer C, Clay K. Hybridization and the colonization of novel habitats by annual sunflowers. Genetica. 2007;129:149–165. doi: 10.1007/s10709-006-9011-y. doi:10.1007/s10709-006-9011-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sætre G.-P, Moum T, Bures S, Kral M, Adamjan M, Moreno J. A sexually selected character displacement in flycatchers reinforces premating isolation. Nature. 1997;387:589–592. doi:10.1038/42451 [Google Scholar]

- Sætre G.-P, Borge T, Lindell J, Moum T, Primmer C.R, Sheldon B.C, Haavie J, Johnson A, Ellegren H. Speciation, introgressive hybridization and nonlinear rate of molecular evolution in flycatchers. Mol. Ecol. 2001;10:737–749. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2001.01208.x. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294x.2001.01208.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato A, O'hUigin C, Figueroa F, Grant P.R, Grant B.R, Klein J. Phylogeny of Darwin's finches as revealed by mtDNA sequences. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:5101–5106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5101. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.9.5101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schluter D. Adaptive radiation along genetic lines of least resistance. Evolution. 1996;50:1766–1774. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1996.tb03563.x. doi:10.2307/2410734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmeller D.S, Seitz A, Crivelli A, Veith M. Crossing species range borders: interspecies gene exchange mediated by hybridogenesis. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2005;272:1625–1631. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3129. doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seehausen O. Hybridization and adaptive radiation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2004;19:198–207. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2004.01.003. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2004.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seehausen O. African cichlid fish: a model system in adaptive radiation research. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2006;273:1987–1998. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3539. doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.3539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stebbins G.L., Jr The role of hybridization in evolution. Proc. Am. Philos. Soc. 1959;103:231–251. [Google Scholar]

- Svärdson G. Significance of introgression in coregonid evolution. In: Lindsey C.C, Woods C.S, editors. Biology of coregonid fishes. University of Manitoba Press; Winnipeg, Canada: 1970. pp. 33–59. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor D.J, Hebert P.D.N. Habitat-dependent hybrid parentage and differential introgression between neighboring sympatric Daphnia species. Proc Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:7079–7083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.7079. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.15.7079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor E.B, Boughman J.W, Groenenboom M, Sniatynski M, Schluter D, Gow J. Speciation in reverse: morphological and genetic evidence of the collapse of a three-spined stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus) species pair. Mol. Ecol. 2006;15:343–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02794.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02794.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thulin C.-G, Tegelström H. Biased geographical distribution of mitochondrial DNA that passed species boundaries from mountain hares to brown hares (genus Lepus): an effect of genetic incompatibility and mating behaviour? J. Zool. (Lond.) 2002;258:299–306. doi:10.1017/S0952836902001425 [Google Scholar]

- Veron J.E.N. Comstock; Ithaca, NY: 1995. Corals in space and time: the biogeography and evolution of the Scleractinia. [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.-R, Szmidt A.E. Hybridization and chloroplast DNA variation in a Pinus species complex from Asia. Evolution. 1995;48:1020–1031. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1994.tb05290.x. doi:10.2307/2410363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wayne R.K. Molecular evolution of the dog family. Trends Genet. 1993;9:218–224. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(93)90122-x. doi:10.1016/0168-9525(93)90122-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]