Abstract

Early-onset generalized dystonia (DYT1) is a debilitating neurological disorder characterized by involuntary movements and sustained muscle spasms. DYT1 dystonia has been associated with two mutations in torsinA that result in the deletion of a single glutamate residue (torsinA ΔE) and six amino-acid residues (torsinA Δ323-8). We recently revealed that torsinA, a peripheral membrane protein, which resides predominantly in the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and nuclear envelope (NE), is a long-lived protein whose turnover is mediated by basal autophagy. Dystonia-associated torsinA ΔE and torsinA Δ323-8 mutant proteins show enhanced retention in the NE and accelerated degradation by both the proteasome and autophagy. Our results raise the possibility that the monomeric form of torsinA mutant proteins is cleared by proteasome-mediated ER-associated degradation (ERAD), whereas the oligomeric and aggregated forms of torsinA mutant proteins are cleared by ER stress-induced autophagy. Our findings provide new insights into the pathogenic mechanism of torsinA ΔE and torsinA Δ323-8 mutations in dystonia and emphasize the need for a mechanistic understanding of the role of autophagy in protein quality control in the ER and NE compartments.

Keywords: Dystonia, autophagy, torsinA, endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation, endoplasmic reticulum, nuclear envelope, protein misfolding, protein quality control

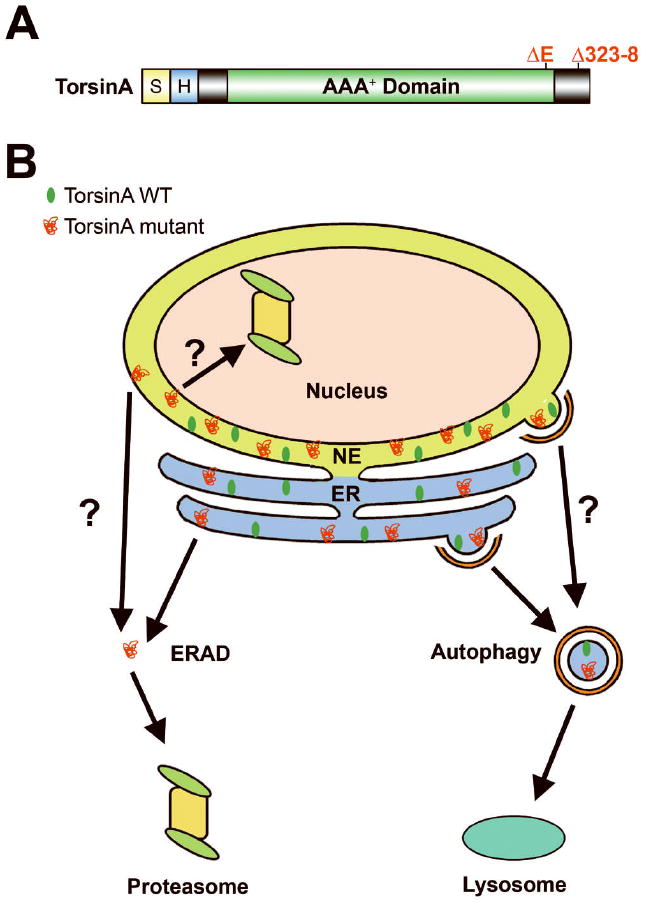

Early-onset generalized dystonia (DYT1) is an autosomal dominant neurological disorder characterized by involuntary movements and prolonged muscle contraction that lead to twisting body motions, tremor, and abnormal posture.1 DYT1 dystonia has been associated with two mutations in torsinA, a 332-amino-acid protein that belongs to the AAA+ (ATPases associated with a variety of cellular activities) superfamily (Fig. 1A). A single glutamate residue deletion at position 302 or 303 (torsinA ΔE) is responsible for a majority of DYT1 cases, and a six-aminoacid deletion (torsinA Δ323-8) was identified in a single family.2, 3 The pathogenic mechanism by which torsinA mutations cause dystonia remains unknown.

Figure 1.

Degradation of torsinA wild-type (WT) and mutant proteins by autophagy. (A) Domain structure of TorsinA. S, ER signal sequence; H, hydrophobic domain; AAA+, ATPases associated with a variety of cellular activities. The locations of dystonia-associated torsinA mutations are indicated on the domain structure. (B) Potential mechanisms for clearance of torsinA WT and mutant proteins. TorsinA WT is recruited to a subdomain of the ER that is sequestered into an autophagosome for lysosomal degradation by basal autophagy. The ER-localized, monomeric form of torsinA mutant proteins are retrotranslocated to the cytosol by ERAD for degradation by the cytosolic proteasome, whereas the nuclear envelope (NE)-localized, monomeric form of torsinA mutant proteins may be retrotranslocated to the nucleus by the inner nuclear membrane-associated ERAD for degradation by the nuclear proteasome. It is also possible that the NE-localized torsinA mutant monomers are retrotranslocated to the cytosol by the outer nuclear membrane-associated ERAD or the mutants may have to migrate to the ER for ERAD-mediated degradation by the cytosolic proteasome. The ER-localized, oligomeric and aggregated forms of torsinA mutant proteins may segregate in a specialized area of the ER for clearance by ER stressinduced autophagy, whereas the NE-localized, oligomeric and aggregated forms of torsinA mutant proteins may be cleared by autophagy via an unknown mechanism.

TorsinA contains an N-terminal endoplasmic reticulum (ER) signal sequence followed by a 20-amino acid hydrophobic domain (Fig. 1A). TorsinA wild-type (WT) is believed to be a peripheral membrane protein that resides predominantly in the ER lumen, whereas torsinA ΔE mutant protein was reported to locate mainly in the nuclear envelope (NE).4-7 Our recent study indicates that torsinA WT is primarily associated with the ER in non-neuronal cells, but in neuronal cells torsinA WT shows a preferential localization to the NE compared to the ER marker KDEL. The NE preference of torsinA is further enhanced by dystonia-associated torsinA ΔE and torsinA Δ323-8 mutations in a neuronal cell-type-specific manner.8 These data suggest that, in addition to functioning in the ER of both neuronal and non-neuronal cells, torsinA has a neuron-specific role in the NE, which is consistent with the neuronal NE phenotype of torsinA knockout and torsinA ΔE knock-in mice.9 The precise function of torsinA in the ER and NE remains unknown, although torsinA has been proposed to act as a molecular chaperone for regulating the organization of the ER and NE compartments or protein trafficking through the ER.10, 11

How are ER/NE-localized torsinA WT and mutant proteins degraded in cells? There are two major intracellular protein degradation systems: the proteasome, which usually mediates selective degradation of short-lived cellular proteins and misfolded proteins, and macroautophagy (hereafter referred to as autophagy), a lysosome-dependent, bulk clearance system for turnover of long-lived proteins and organelles.12-14 Our study revealed that torsinA WT is a very stable protein with a half-life of ~3.5 days.8 Previous studies have shown that most ER resident proteins have a long half-life, in the order of 2 to 6 days, although a small number of ER resident proteins have a much shorter half-life.15, 16 The mechanism governing the normal turnover of ER resident proteins remains unclear. We found that torsinA WT is degraded by autophagy but not the proteasome.8 Our data raises the possibility that torsinA WT and other long-lived ER resident proteins may segregate in a subdomain of the ER which is targeted for degradation by basal autophagy (Fig. 1B).

Our study indicated that torsinA ΔE and torsinA Δ323-8 mutations destabilize torsinA considerably, reducing the half-life to ~18 h.8 These findings suggest that dystonia-associated mutations induce misfolding of torsinA into non-native conformations that can be recognized and selected by the cellular protein quality-control machinery for destruction. We found that, unlike torsinA WT, both torsinA ΔE and torsinA Δ323-8 mutants are degraded by the proteasome.8 It is unclear how torsinA mutants are specifically recognized and transported to the proteasome for degradation. One possibility is that dystonia mutation-induced torsinA folding defects are selectively recognized by an ER chaperone or E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase, which cooperates with other components of the ER-associated degradation (ERAD) system to facilitate retrotranslocation of torsinA mutants from the ER lumen to the cytosol for degradation by the cytosolic proteasome (Fig. 1B).17-19 The NE-localized torsinA mutant proteins might be retrotranslocated from the NE lumen to the nucleus by the inner nuclear membrane-associated ERAD for degradation by the nuclear proteasome (Fig. 1B), as shown for some mutant NE proteins in yeast.20-22 Alternatively, the NE-localized torsinA mutants might be retrotranslocated to the cytosol by the outer nuclear membrane-associated ERAD or they might have to migrate to the ER prior to ERAD-mediated retrotranslocation for degradation by the cytosolic proteasome (Fig. 1B).

Although the proteasome plays an important role in the clearance of torsinA mutants, proteasome activity does not fully account for their disposal. We found that the degradation of both torsinA ΔE and torsinA Δ323-8 mutants is also mediated by autophagy.8 Our data support the emerging view that autophagy provides an alternative ER quality control system for disposal of misfolded proteins.23, 24 It has become clear that oligomeric and aggregated proteins are resistant to proteasomal degradation and can actually impair the proteasome function.14, 25 Our finding that torsinA mutants are degraded by both the proteasome and autophagy raises the possibility that the monomeric form of torsinA mutants are cleared by proteasome-mediated ERAD, whereas the oligomeric and aggregated forms of torsinA mutants are cleared by autophagy.

Recent evidence suggests that ER stress resulting from accumulation of misfolded proteins can induce a specific type of autophagy, termed reticulophagy or ER-phagy, which selectively sequesters portions of the ER for lysosomal degradation.26,27 The origin of the autophagosome membrane for sequestering ER fragments remains unclear, but the ER has been proposed to be a membrane source for autophagosome formation.26, 27 It is possible that the oligomeric and aggregated forms of torsinA mutants may segregate in a specialized area of the ER which is engulfed and cleared by ER stress-induced reticulophagy (Fig. 1B). The role of autophagy in the quality control of the NE compartment remains unknown. In yeast, a process known as piecemeal microautophagy of the nucleus (PMN) is used to target portions of the NE for degradation by the vacuole, the yeast equivalent of the mammalian lysosome.28, 29 It is tempting to speculate that the NE-localized torsinA mutant proteins might be cleared by an autophagy process that is analogous to PMN or reticulophagy (Fig. 1B). Further investigation of the molecular pathways controlling the degradation of dystonia-associated torsinA mutants should advance our knowledge of the protein quality control mechanisms in the ER and NE, and facilitate the development of new therapeutic strategies for treating dystonia.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants NS054334 (L.M.G.), ES015813 (L.L.), GM082828 (L.L.), and NS050650 (L.S.C.).

ABBREVIATIONS

- DYT1

Early onset generalized dystonia

- WT

Wild-type

- ER

Endoplasmic reticulum

- NE

Nuclear envelope

- ERAD

Endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation

Footnotes

Addendum to: Dystonia-associated torsinA mutations cause premature degradation of torsinA protein and cell-type-specific mislocalization to the nuclear envelope Lisa M. Giles, Jue Chen, Lian Li, and Lih-Shen Chin. Hum Mol Genet 2008; 17: 2712-22

References

- 1.Bressman SB, Fahn S, Ozelius LJ, Kramer PL, Risch NJ. The DYT1 mutation and nonfamilial primary torsion dystonia. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:681–2. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.4.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ozelius LJ, Hewett JW, Page CE, Bressman SB, Kramer PL, Shalish C, de Leon D, Brin MF, Raymond D, Corey DP, Fahn S, Risch NJ, Buckler AJ, Gusella JF, Breakefield XO. The early-onset torsion dystonia gene (DYT1) encodes an ATP-binding protein. Nat Genet. 1997;17:40–8. doi: 10.1038/ng0997-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leung JC, Klein C, Friedman J, Vieregge P, Jacobs H, Doheny D, Kamm C, DeLeon D, Pramstaller PP, Penney JB, Eisengart M, Jankovic J, Gasser T, Bressman SB, Corey DP, Kramer P, Brin MF, Ozelius LJ, Breakefield XO. Novel mutation in the TOR1A (DYT1) gene in atypical early onset dystonia and polymorphisms in dystonia and early onset parkinsonism. Neurogenetics. 2001;3:133–43. doi: 10.1007/s100480100111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gonzalez-Alegre P, Paulson HL. Aberrant cellular behavior of mutant torsinA implicates nuclear envelope dysfunction in DYT1 dystonia. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2593–601. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4461-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goodchild RE, Dauer WT. Mislocalization to the nuclear envelope: an effect of the dystonia-causing torsinA mutation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:847–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0304375101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naismith TV, Heuser JE, Breakefield XO, Hanson PI. TorsinA in the nuclear envelope. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:7612–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308760101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellenberg J, Siggia ED, Moreira JE, Smith CL, Presley JF, Worman HJ, Lippincott-Schwartz J. Nuclear membrane dynamics and reassembly in living cells: targeting of an inner nuclear membrane protein in interphase and mitosis. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:1193–206. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.6.1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giles LM, Chen J, Li L, Chin LS. Dystonia-associated mutations cause premature degradation of torsinA protein and cell-type-specific mislocalization to the nuclear envelope. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:2712–22. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodchild RE, Kim CE, Dauer WT. Loss of the dystonia-associated protein torsina selectively disrupts the neuronal nuclear envelope. Neuron. 2005;48:923–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Breakefield XO, Kamm C, Hanson PI. TorsinA: movement at many levels. Neuron. 2001;31:9–12. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00350-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breakefield XO, Blood AJ, Li Y, Hallett M, Hanson PI, Standaert DG. The pathophysiological basis of dystonias. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:222–34. doi: 10.1038/nrn2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubinsztein DC. The roles of intracellular protein-degradation pathways in neurodegeneration. Nature. 2006;443:780–6. doi: 10.1038/nature05291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ciechanover A. Intracellular protein degradation: from a vague idea thru the lysosome and the ubiquitin-proteasome system and onto human diseases and drug targeting. Cell death and differentiation. 2005;12:1178–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ding WX, Yin XM. Sorting, recognition and activation of the misfolded protein degradation pathways through macroautophagy and the proteasome. Autophagy. 2008;4:141–50. doi: 10.4161/auto.5190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arias IM, Doyle D, Schimke RT. Studies on the synthesis and degradation of proteins of the endoplasmic reticulum of rat liver. J Biol Chem. 1969;244:3303–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Omura T, Siekevitz P, Palade GE. Turnover of constituents of the endoplasmic reticulum membranes of rat hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 1967;242:2389–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kleizen B, Braakman I. Protein folding and quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004;16:343–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kincaid MM, Cooper AA. ERADicate ER stress or die trying. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:2373–87. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meusser B, Hirsch C, Jarosch E, Sommer T. ERAD: the long road to destruction. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:766–72. doi: 10.1038/ncb0805-766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McBratney S, Winey M. Mutant membrane protein of the budding yeast spindle pole body is targeted to the endoplasmic reticulum degradation pathway. Genetics. 2002;162:567–78. doi: 10.1093/genetics/162.2.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deng M, Hochstrasser M. Spatially regulated ubiquitin ligation by an ER/nuclear membrane ligase. Nature. 2006;443:827–31. doi: 10.1038/nature05170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ravid T, Kreft SG, Hochstrasser M. Membrane and soluble substrates of the Doa10 ubiquitin ligase are degraded by distinct pathways. EMBO J. 2006;25:533–43. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yorimitsu T, Klionsky DJ. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: a new pathway to induce autophagy. Autophagy. 2007;3:160–2. doi: 10.4161/auto.3653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yorimitsu T, Klionsky DJ. Eating the endoplasmic reticulum: quality control by autophagy. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:279–85. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olzmann JA, Li L, Chin LS. Aggresome formation and neurodegenerative diseases: therapeutic implications. Current medicinal chemistry. 2008;15:47–60. doi: 10.2174/092986708783330692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bernales S, Schuck S, Walter P. ER-phagy: selective autophagy of the endoplasmic reticulum. Autophagy. 2007;3:285–7. doi: 10.4161/auto.3930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernales S, McDonald KL, Walter P. Autophagy counterbalances endoplasmic reticulum expansion during the unfolded protein response. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kvam E, Goldfarb DS. Nucleus-vacuole junctions in yeast: anatomy of a membrane contact site. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:340–2. doi: 10.1042/BST0340340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roberts P, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Kvam E, O’Toole E, Winey M, Goldfarb DS. Piecemeal microautophagy of nucleus in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:129–41. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-08-0483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]