Abstract

Arrestins mediate G protein-coupled receptor desensitization, internalization, and signaling. Dopamine D2 and D3 receptors have similar structures but distinct characteristics of interaction with arrestins. The goals of this study were to compare arrestin-binding determinants in D2 and D3 receptors other than phosphorylation sites and to create a D2 receptor that is deficient in arrestin binding. We first assessed the ability of purified arrestins to bind to glutathione transferase (GST) fusion proteins containing the receptor third intracellular loops (IC3). Arrestin3 bound to IC3 of both D2 and D3 receptors, with the affinity and localization of the binding site indistinguishable between the receptor subtypes. Mutagenesis of the GST-IC3 fusion proteins identified an important determinant of the binding of arrestin3 in the N-terminal region of IC3. Alanine mutations of this determinant (IYIV212–215) in the full-length D2 receptor generated a signaling-biased receptor with intact ligand binding and G-protein coupling and activation, but deficient in receptor-mediated arrestin3 translocation to the membrane, agonist-induced receptor internalization, and agonist-induced desensitization in human embryonic kidney 293 cells. This mutation also decreased arrestin-dependent activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases. The finding that nonphosphorylated D2-IC3 and D3-IC3 have similar affinity for arrestin is consistent with previous suggestions that the differential effects of D2 and D3 receptor activation on membrane translocation of arrestin and receptor internalization are due, at least in part, to differential phosphorylation of the receptors. In addition, these results imply that the sequence IYIV212–215 at the N terminus of IC3 of the D2 receptor is a key element of the arrestin binding site.

The nonvisual arrestins arrestin2 and -3 (also termed β-arrestin1 and -2) are cytosolic proteins involved in homologous desensitization and resensitization of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), and serve as adaptors to link GPCRs to the endocytotic machinery. Arrestins also redirect GPCRs to alternative, G protein-independent signaling pathways (Pierce and Lefkowitz, 2001). Although most or all GPCRs bind arrestins, and phosphorylated serine and threonine residues often comprise part of the arrestin binding site, little information is available concerning other structural features of receptors that cause them to be recognized by arrestins.

Three D2-like receptors, D2, D3, and D4, have been identified. D2-like receptors are the major targets of antipsychotic drugs. When activated, they couple to the Gi/o family of G proteins and regulate adenylate cyclases, potassium channels, calcium channels, and other effectors (Neve et al., 2004). Despite close sequence homology between D2 and D3 receptors, agonist-induced receptor phosphorylation, arrestin translocation to the plasma membrane, and receptor internalization for the two subtypes are dramatically different. These differences can be attributed primarily to IC2 and IC3 of the two receptors (Kim et al., 2001).

Numerous studies have examined the roles of IC2, IC3, and the carboxyl terminus of GPCRs in receptor internalization. In the classic model of G protein-coupled receptor kinase- (GRK-) and arrestin-mediated intracellular trafficking of GPCRs, GRK phosphorylates residues in the intracellular segments of receptors, recruiting arrestin to bind to the phosphorylated residues and to other residues whose accessibility is regulated by receptor phosphorylation and by the activation state of the receptor (Lee et al., 2000; Pierce and Lefkowitz, 2001; Kim et al., 2004; Gurevich and Gurevich, 2006). One way to quantify the contribution of nonphosphorylated residues to the binding of arrestin is to use peptides representing intracellular receptor domains, either measuring their ability to inhibit arrestin binding to receptors or measuring direct binding of arrestin to the receptor fragments. Such studies have demonstrated that arrestin binds to multiple unphosphorylated intracellular domains of GPCRs (Wu et al., 1997; Gelber et al., 1999; Cen et al., 2001; Han et al., 2001; DeGraff et al., 2002; Macey et al., 2004, 2005).

To identify nonphosphorylated arrestin-binding sites of D2 and D3 receptors, we generated glutathione transferase (GST) fusion proteins of intracellular loops of the receptors and used them in direct binding assays with purified arrestins. We now report that arrestin3 bound avidly to IC3 of both receptors. Binding of arrestin3 to D2-IC3 required four to five residues at the N terminus of the loop. Simultaneous substitution of alanine for four of these residues in the full-length D2 receptor abolished receptor-mediated recruitment of arrestin3 to the membrane, agonist-induced receptor internalization, and agonist-induced desensitization of cyclic AMP accumulation in HEK 293 cells and decreased arrestin-dependent activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs), without altering high- or low-affinity agonist binding to the receptor and the potency of agonist for inhibition of cyclic AMP accumulation. Our data suggest that the D2-A4 mutant differentiates between G protein- and arrestin-dependent responses to receptor activation.

Materials and Methods

Materials. [3H]Spiperone (83 Ci/mmol) was purchased from GE Healthcare (Chalfont St. Giles, Buckinghamshire, UK), and [3H]-sulpiride (77.7 Ci/mmol) from PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences (Waltham, MA). Serum was purchased from Hyclone Laboratories (Logan, UT). Dopamine, (+)-butaclamol, haloperidol, and most reagents, including culture medium, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Antibodies used include mouse anti-rat arrestin2 (BD Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY), mouse anti-human arrestin3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), rabbit anti-dually phosphorylated (i.e., activated) ERKs (Biosource International, Camarillo, CA), p44/42 MAP kinase antibody (i.e., total ERKs; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), and secondary antibodies horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (both from Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). The cyclic AMP enzyme immunoassay kit was from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Arrestin-3-pCMV5 was a generous gift from Dr. Marc Caron (Duke University, Durham, NC).

Generation of GST Fusion Proteins and D2 Receptor Constructs. For construction of the GST fusion proteins, the IC3 of the rat dopamine D2L receptor (D2-IC3), amino acids 211 to 371, and IC3 of the rat dopamine D3 receptor (D3-IC3), amino acids 210 to 372, were amplified by polymerase chain reaction, subcloned into SpeIXhoI sites in pET-41a(+) (Novagen, Madison, WI), transformed into NovaBlue competent cells, sequenced, and subsequently transformed into Rosetta 2(DE3) competent cells (Novagen). For purification of GST fusion proteins, Rosetta 2(DE3) cells were grown in 2× yeast extract tryptone medium containing kanamycin (50 μg/ml) at 37°C to A600 = 0.8 and induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside for 2 h at 32°C. Cells were pelleted, resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.5 mg/ml lysozyme, pH 8.0) containing Complete protease inhibitor tablet (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), and incubated for 20 min with gentle rotation at room temperature. The homogenates were clarified by centrifugation, and supernatants were applied to microcentrifuge tubes containing Glutathione Sepharose 4B beads (GE Healthcare), and purified as described by the manufacturer. To quantify the amounts of fusion proteins, SDS sample loading buffer was applied to beads bound with purified proteins, samples were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and the gel was stained with Gel Code Blue (Pierce). Bovine serum albumin was used as a standard.

The D2-IC3 substitution mutants, the A4 mutant (myc-D2-IYIV212–215A4), and the IC3ΔMID mutant (myc-D2-IC3ΔMID) were constructed using the QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) through one or more mutagenesis steps, with GST-D2-IC3 or the myc-D2 receptor as a template. The IC3 truncation mutants were generated using a QuikChange method modified to introduce large truncations (Makarova et al., 2000) with GST-D2-IC3 or GST-D3-IC3 plasmid as template. The myc-D2 receptor (referred to herein as wild-type D2 to differentiate it from the D2-A4 mutant) was constructed by cloning a rat D2L receptor cDNA into SfiI-XhoI sites in the pCMV-Myc vector (Clontech, Mountain View, CA).

Purified Arrestin Binding to GST Fusion Proteins. To obtain purified arrestins, plasmids were expressed in BL21 cells and arrestins purified using heparin-Sepharose chromatography, followed by Q-Sepharose chromatography (Han et al., 2001). GST fusion proteins bound to glutathione Sepharose 4B beads were incubated with purified bovine arrestin2 or arrestin3 in arrestin binding buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.2, Complete protease inhibitor tablet, and 0.1% Triton X-100) for 30 min at room temperature. Incubation mixtures were washed four times in wash buffer (arrestin binding buffer without protease inhibitors), and the proteins were released with SDS sample loading buffer. Proteins were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to PVDF membranes that were then blocked with 5% nonfat-dry milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS), and detected by immunoblotting using anti-arrestin2 (1:300 dilution in TBS) or anti-arrestin3 (1:400 dilution in TBS) antibody, with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:10,000 dilution in TBS) as secondary antibody. Visualization of the secondary antibody was performed using the Super-Signal West Pico Chemiluminescence kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and quantified by IP Lab (Scanalytics, Fairfax, VA). The amount of bound arrestin2 or arrestin3 was calculated from linear regression of a standard curve generated using background optical density (i.e., no arrestin) and 3 to 6 concentrations of arrestin2 or arrestin3 ranging between 0.25 and 20 ng. Saturation analysis of the binding of arrestin was carried out by incubating various concentrations of arrestin2 or -3 with a fixed concentration of GST alone (150 or 175 ng) or GST-IC3 (300 ng) for 30 min at room temperature. The resulting concentration-response curves were analyzed by nonlinear regression using Prism 3.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) and statistical comparisons of the curves were made using two-way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni post test analysis. In experiments in which only one concentration of arrestin was used, statistical significance was evaluated using a paired t test.

Internalization Assay. Internalization was measured using the intact cell [3H]sulpiride binding assay described by Itokowa et al. (1996). HEK 293 cells grown to 80% confluence were cotransfected with 30 ng of D2 wild type, 10 μg D2-A4 mutant receptor DNA (the A4 mutant was expressed on the membrane at a lower density so a greater amount of DNA was used to achieve similar expression levels), or 100 ng of D2-IC3ΔMID mutant receptor DNA and 3 μg of arrestin3-pCMV5 using Lipofectamine2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Cells were split into two plates after 12 h, and 2 days later rinsed once with prewarmed calcium- and magnesium-free phosphate-buffered saline (CMF-PBS; 138 mM NaCl, 4.1 mM KCl, 5.1 mM sodium phosphate, 5 mM potassium phosphate, and 0.2% glucose, pH 7.4), and preincubated for 15 min with prewarmed CO2-saturated serum-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, at 37°C. Cells were stimulated with 10 μM dopamine in the same HEPES-buffered medium at 37°C for 20 min. Stimulation was terminated by quickly cooling the plates on ice and washing the cells three times with ice-cold CMF-PBS, after which cells were removed from the plate in 2 ml of ice-cold CMF-PBS assay buffer (CMF-PBS containing 2 mM EDTA and 0.001% bovine serum albumin). Cells were gently mixed, added to assay tubes in a final volume of 250 μl with [3H]sulpiride (5 nM final concentration), and incubated at 4°C for 150 min in the absence and presence of unlabeled haloperidol (10 μM final concentration). The assay was terminated by filtration through GF/C filters (Whatman, Clifton, NJ) presoaked with 0.05% polyethylenimine using a 96-well cell harvester (Tomtec, Orange, CT) and ice-cold wash buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, and 0.9% NaCl). Filters were allowed to dry, and BetaPlate Scint scintillation fluid (50 μl) was added to each sample. Radioactivity on the filters was determined using a Wallac 1205 BetaPlate scintillation counter (PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences). To confirm the expression of arrestin3, the remaining cells were pelleted and resuspended with ice-cold lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES, 20 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5% CHAPS, and Complete protease inhibitor tablet). The suspensions were gently rocked on an orbital shaker at 4°C for 60 min and then were centrifuged at 100,000g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant was saved and immunoblotting of overexpressed arrestin3 was performed as described under Purified Arrestin Binding to GST Fusion Proteins.

Arrestin3 Translocation. Transient expression of wild-type D2 or D2-A4 mutant receptor with arrestin3 and dopamine stimulation of cells were performed as described under Internalization Assay, except that each plate was split into three plates after transfection (one plate for the intact cell [3H]sulpiride binding to detect the levels of receptor expression, performed as described under Internalization Assay but without dopamine treatment). Stimulation was terminated by quickly cooling the plates on ice and washing the cells once with ice-cold CMF-PBS. Cells were lysed with 1 ml of ice-cold lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES, 20 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, and Complete protease inhibitor tablet), scraped, collected, homogenized with a glass-Teflon homogenizer, and sonicated for 8 to 10 s. Samples were centrifuged at 1000g for 10 min at 4°C. Supernatants were transferred to new centrifuge tubes and centrifuged at 100,000g for 30 min at 4°C. Supernatants were collected; pellets were rinsed carefully with ice-cold CMF-PBS and then resuspended with 100 μl of CMFPBS. The abundance of arrestin3 in both pellet and supernatant fractions was quantified by immunoblotting as described above, except with a 1:100 dilution of the anti-arrestin3 antibody and the addition of 0.1% Tween 20 and 5% dry milk to the incubations with primary and secondary antibodies.

Radioligand Binding Assays. Cells expressing wild-type D2 receptor or the D2-A4 mutant were lysed in ice-cold hypotonic buffer (1 mM Na+HEPES, pH 7.4, and 2 mM EDTA) for 15 min, scraped from the plate, and centrifuged at 17,000g for 20 min. The resulting crude membrane fraction was resuspended with a Polytron homogenizer (Brinkmann Instruments, Westbury, NY) at setting 6 for 8 to 10 s in TBS for saturation assays of the binding of [3H]spiperone, or resuspended in preincubation buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.9% NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM dithiothreitol), preincubated for 30 min at 37°C, centrifuged at 17,000g for 10 min, and resuspended again in Tris assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 6 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.001% bovine serum albumin, 0.002% ascorbic acid) for competition binding studies in which dopamine displacement of the binding of [3H]spiperone was assessed. Membranes (40–100 μg protein) were incubated in duplicate in a total reaction volume of 1 ml with [3H]spiperone at concentrations ranging from 0.01–0.6 nM for saturation binding or ∼0.1 nM with the appropriate concentration of the competing drug dopamine for competition binding. (+)-Butaclamol (2 μM final) was used to define nonspecific binding. Reactions were incubated at 37°C for 45 min and terminated by filtration as described above. Data for saturation and competition binding were analyzed by nonlinear regression using the computer program Prism 3.0 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA) to determine Kd and IC50 values. Apparent affinity (Ki) values were calculated from the IC50 values by the method of Cheng and Prusoff (Cheng and Prusoff, 1973). In all assays, the free concentration of radioligand was calculated as the concentration added minus the concentration specifically bound.

Cyclic AMP Accumulation Assay. Wild-type or mutant D2 receptors in pCMV-Myc were cotransfected with pcDNA3.1 (for G418 resistance) into HEK 293 cells using Lipofectamine2000, and clonal cell lines stably expressing the receptors were isolated after selection with G418 (800 μg/ml). Cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 5% iron-supplemented calf bovine serum, 5% fetal bovine serum, and 600 μg/ml G418 at 37°C and 10% CO2. For production of cell lines overexpressing arrestin3, stable D2 cell lines were transiently transfected with 3 μg arrestin3-pCMV5. The cyclic AMP accumulation assay was performed as described by Liu et al. (2007), except that the agonist dopamine was used and the assay was performed two days after transient transfection. The expression of cell surface receptor was determined by intact cell [3H]sulpiride binding. The overexpression of arrestin3 was confirmed by immunoblotting. In some experiments, cells were pretreated with 10 μM dopamine for 20 min at 37°C, followed by three rinses with ice-cold Earle’s balanced salt solution, before measuring dopamine inhibition of forskolin-stimulated cyclic AMP accumulation for 10 min at 37°C.

Immunodetection of ERKs. Stable expression of D2 receptors and transient expression of arrestin3 were performed as described under Cyclic AMP Accumulation Assay. For detection of phosphospecific ERKs, PVDF membranes were probed with rabbit anti-dually phosphorylated ERKs [1/100 dilution in TBST (TBS + 0.1% Tween 20) with 5% dry milk], followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1/200 dilution in TBST with 1% dry milk). Phospho-ERKs were visualized and quantified as described for arrestins. Multiple dilutions of sample WT+arr-DA were used to verify that the concentration of phospho-ERKs varied linearly with optical density. For detection of total ERKs, PVDF membranes were blocked with 5% dry milk in TBST and detected by immunoblotting using p44/42 MAP kinase antibody (1/1000 dilution in TBST), with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1/1000 dilution in TBST) as secondary antibody.

Results

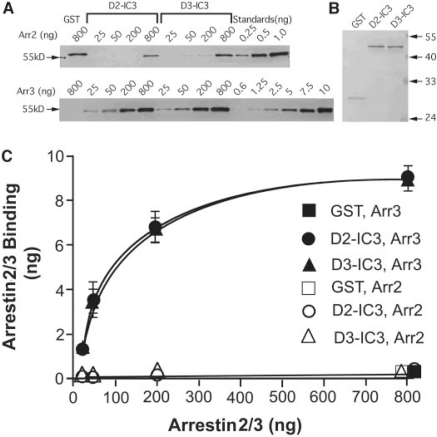

Robust Binding of Arrestin3 to IC3. GST-D2-IC3 and GST-D3-IC3 were constructed and the binding of arrestin determined using an in vitro GST pull-down assay. To identify conditions for equilibrium binding, the rate of association of arrestin3 with GST-D2-IC3 was determined. The half-time for binding was approximately 2 min, and the binding approached equilibrium within 15 min (data not shown). Therefore, GST binding assays were carried out for 30 min. Arrestin3 bound avidly to both GST-D2-IC3 and GST-D3-IC3, showing no apparent difference between the two IC3 fusion proteins (Fig. 1, Table 1). Arrestin2 bound weakly to both fusion proteins (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Binding of arrestins to GST-D2-IC3 and GST-D3-IC3 fusion proteins. GST alone (GST, 150 ng) or receptor third intracellular loop GST fusion proteins (GST-D2-IC3 and GST-D3-IC3, 300 ng) were incubated with the indicated amount of arrestin2 or arrestin3. The amount of arrestin that coeluted with GST or the GST fusion proteins was determined by immunoblotting with anti-arrestin antibodies. Results were quantified using standard curves constructed with known amounts of arrestin2 and arrestin3. A, immunoblots are shown from an experiment representative of 4 independent experiments. Arrestin standards are shown on the right of each blot. B, the protein-stained gel demonstrates that equal amounts of GST-D2-IC3 and GST-D3-IC3 were included in the reactions. C, results shown are the mean ± S.E.M. for the binding of arrestins to IC3 fusion proteins. The amount of arrestin bound is plotted against the amount of arrestin included in the pull-down assay.

TABLE 1.

Saturation analysis of binding of arrestin3 to receptor fragments

Kd values were calculated based on the molecular mass of arrestin3 (∼54 kDa). Bmax values represent the amount of arrestin3 bound to 300 ng of GST-IC3 (∼44 kDa). Each value represents the mean ± S.E. of three or more independent experiments.

| Fusion Protein | Arrestin3

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Kd | Bmax | |

| nM | ng | |

| GST-D2-IC3 | 72 ± 14 | 10.1 ± 0.6 |

| GST-D3-IC3 | 79 ± 14 | 10.2 ± 0.6 |

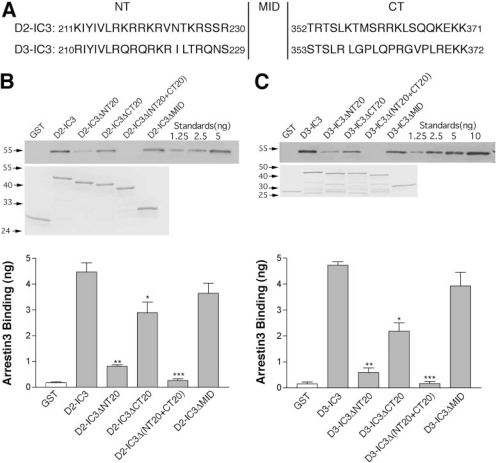

Identification of Arrestin3 Binding Sites within IC3 of the D2 and D3 Receptors. Intracellular residues in proximity to the transmembrane domains are critical for GPCR interactions with many cytosolic proteins, so we made truncation/deletion mutants to identify regions of arrestin3 binding to IC3, focusing on residues close to those transmembrane domains (Fig. 2A). GST pull-down assays revealed that deletion of the first 20 residues of D2-IC3 (D2-IC3ΔNT20) dramatically decreased its arrestin-binding capability; when the last 20 amino acids were deleted (D2-IC3ΔCT20), the binding capability also decreased, though to a lesser extent; when both the first and last 20 residues were deleted [D2-IC3Δ(NT20+CT20)], little binding was observed (Fig. 2B). In contrast, deletion of ∼120 residues comprising all of IC3 except the 20 residues at each terminus (D2-IC3ΔMID) had little effect on the binding of arrestin. The arrestin binding patterns of the truncation/deletion mutants of the D3 receptor were the same as for the D2 receptor (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Binding of arrestin3 to D2 and D3 receptor IC3 truncation mutants. A, alignment of IC3 from the rat D2 and D3 dopamine receptors. Each IC3 is divided into NT (20 residues), MID (121 residues not shown for D2 and 123 residues for D3), and CT (20 residues). B and C, purified GST or GST fusion proteins (ranging from 500 to 800 ng to keep the molar concentration constant) were incubated with 100 ng of purified arrestin3, and the amount of arrestin bound was determined by quantitative immunoblotting. Top, representative arrestin immunoblots are shown. The amount of bound arrestin was quantified using a standard curve constructed with known amounts of arrestin as shown on the right of each blot. Middle, protein-stained gels used to verify the size of the truncation mutants and to quantify the amount of each fusion protein are shown. Bottom, the results shown are the mean ± S.E.M. from four independent experiments (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 versus the respective wild-type fusion protein by paired t test).

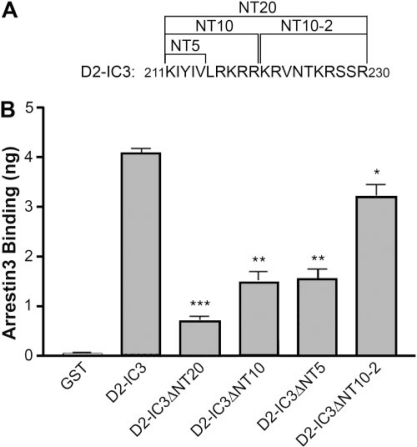

Having localized arrestin3 binding to the first and last 20 residues of IC3, with the N-terminal segment playing a more important role, we constructed additional N-terminal truncation mutants of D2-IC3 in which the first 5 or 10 or the second 10 amino acids were deleted (Fig. 3A). In the GST pull-down assay, deletion of either the first five (D2-IC3ΔNT5) or 10 (D2-IC3ΔNT10) residues decreased arrestin binding by approximately 60%, whereas deletion of the second 10 residues (D2-IC3ΔNT10–2) had little effect (Fig. 3B). We also made smaller C-terminal truncation/deletion mutants, deleting the last 5 or 10 or the penultimate 10 residues, but none of these deletions caused a significant reduction in the binding of arrestin (data not shown). This is consistent with the lesser role of the C terminus suggested by the 20-residue truncation and implies that any contiguous 10 residues in the C terminus are sufficient for the smaller contribution of the C terminus to the binding of arrestin.

Fig. 3.

Binding of arrestin3 to truncation mutants of the amino-terminal region of the D2 receptor IC3. A, sequence of the 20 amino acids in the amino-terminal region of D2-IC3. The first 5 or 10 or the second 10 amino acids were deleted to form the indicated mutants. B, purified GST or GST fusion proteins (400 ng) were incubated with 100 ng of purified arrestin3, and the amount of arrestin bound was determined by quantitative immunoblotting. The results shown are the mean ± S.E.M. from four independent experiments (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 versus D2-IC3 by paired t test).

Because most of the effect of deleting the N-terminal 20 residues of D2-IC3 could be attributed to the first five residues (D2-IC3ΔNT5), we made additional mutations within this segment (Fig. 4A). Deletion of the first three residues (D2-IC3ΔNT3) had no effect on the binding of arrestin3 (Fig. 4B). On the other hand, deletion of D2-IC3 residues 2 to 5 (IYIV212–215 in the D2 receptor, D2-IC3ΔIYIV) was as deleterious to the binding of arrestin as deletion of the first five residues (D2-IC3ΔNT5) (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Binding of arrestin3 to three-, four-, and five-residue deletion mutants and four- and five-residue substitution mutants of the amino-terminal region of D2-IC3. A, sequence of amino acids in the amino-terminal region of D2-IC3, along with the name of each construct, where Δ denotes the residues that were deleted. B, purified GST or GST fusion proteins (600 ng) were incubated with 100 ng of purified arrestin3, and the amount of arrestin bound was determined by quantitative immuno-blotting. Results shown are the mean ± S.E.M. from four or five independent experiments. (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 versus D2-IC3 by paired t test).

Within the cytosolic domains of many integral membrane proteins, the motif YXXϕ (where Y is tyrosine, X is any amino acid, and ϕ is an amino acid with a bulky hydrophobic group) mediates endocytosis and other intracellular trafficking events (Boll et al., 1996; Collins et al., 2002; Vogt et al., 2005). A copy of this motif, YIVL213–216, is at positions 3 to 6 of D2-IC3, and a deletion mutant of residues 2 to 6 that removes the entire motif (D2-IC3ΔIYIVL) caused a 90% loss of arrestin binding that was slightly greater than the loss of binding to D2-IC3ΔIYIV (Fig. 4, A and B) and similar to the 83% loss of binding caused by the N-terminal 20-residue truncation (D2-IC3ΔNT20; Fig. 3). Finally, we mutated IYIV212–215 or IYIVL212–216 to alanines, creating the substitution mutants D2-IC3IYIV212–215A4 and D2-IC3IYIVL212–216A5, which correspond to the deletion mutants D2-IC3ΔIYIV and D2-IC3ΔIYIVL (Fig. 4A). Alanine substitutions were at least as effective as corresponding deletion mutations at decreasing the binding of arrestin (Fig. 4B).

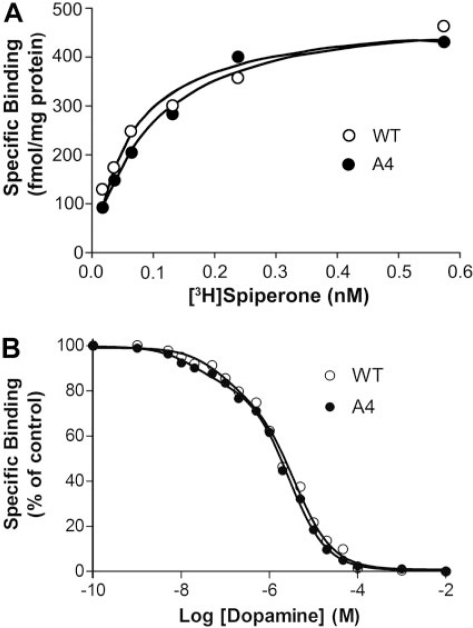

The A4 Mutation Had No Effect on D2 Receptor Affinity for Ligands. The effect of the A4 (IYIV212–215A4) mutation in the context of the full-length D2 receptor was evaluated by analysis of radioligand binding to membranes prepared from HEK 293 cells transiently expressing wild type D2 and D2-A4 mutant receptors. Saturation analysis of the binding of the D2-selective antagonist radioligand, [3H]spiperone, yielded Kd values of 83 ± 13 and 86 ± 4 pM for D2 and D2-A4 receptors, respectively (Table 2; Fig. 5A). Competition binding analysis of the ability of dopamine to decrease the binding of [3H]spiperone indicated that high- and low-affinity binding of dopamine to the A4 mutant was indistinguishable from binding to the wild type D2 receptor (Table 2; Fig. 5B), suggesting that the A4 mutation did not alter D2 receptor affinity for ligands or coupling to G proteins.

TABLE 2.

Binding characteristics of the wild type and A4 mutant dopamine D2 receptors

Affinity values for [3H]spiperone (Kd) were determined by saturation analyses. The apparent affinity values for dopamine were determined by inhibition of the binding of [3H]spiperone, followed by nonlinear regression analysis of the competition curves. Two-site fits generated values for binding sites with high affinity (Kihigh) and low affinity (Kilow) for dopamine. Each value represents the mean ± S.E. of three or more independent experiments.

| Receptor | [3H]Spiperone Kd | Dopamine

|

Receptor in High-Affinity State | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kihigh | Kilow | |||

| pM | nM | % | ||

| D2 wild type | 83 ± 13 | 9.0 ± 2.9 | 4.3 ± 0.5 | 22.1 ± 3.5 |

| D2-A4 | 86 ± 4 | 11.2 ± 3.2 | 3.6 ± 0.7 | 22.7 ± 3.4 |

Fig. 5.

Ligand binding properties of the D2-A4 mutant receptor. A, saturation analysis of the binding of the D2 receptor antagonist [3H]spiperone to membrane preparations from HEK 293 cells expressing wild-type D2 or D2-A4 receptors. Data are plotted as specific binding (femtomoles per milligram of protein) versus the free concentration of radioligand. B, inhibition of the binding of [3H]spiperone by dopamine. Data are plotted as a percentage of specific binding in the absence of dopamine versus the logarithm of the concentration of dopamine. In both A and B, the experiment shown is representative of three or more independent experiments.

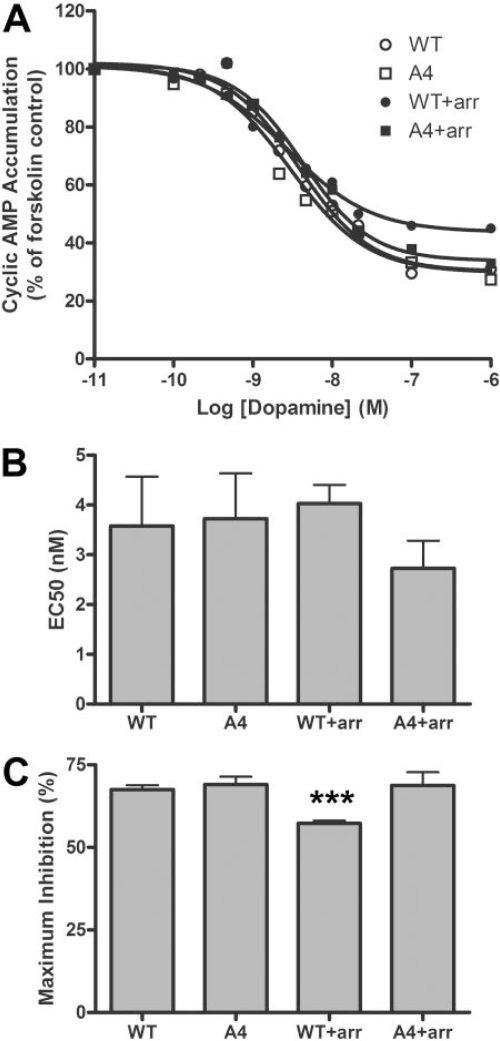

Inhibition of Cyclic AMP by D2-A4. The ability of the A4 mutant to inhibit adenylate cyclase was also characterized. The potency of the agonist was unchanged by the mutation, in either the absence or the presence of overexpressed arrestin3 (Fig. 6A and B). Likewise, maximal inhibition of cyclic AMP accumulation did not differ significantly between wild-type D2 and D2-A4 in the absence of added arrestin (Fig. 6C), indicating that the A4 mutation did not affect receptor activation of the G proteins mediating inhibition of adenylate cyclase. Overexpression of arrestin3 significantly decreased D2 receptor-mediated maximum inhibition of cyclic AMP accumulation (57 ± 1%), whereas the maximum inhibition mediated by the A4 mutant was not altered (69 ± 4%), perhaps reflecting the consequences of differential arrestin translocation and receptor desensitization and internalization (but see The A4 Mutation Abolished Desensitization of Cyclic AMP Accumulation).

Fig. 6.

Dopamine inhibition of forskolin-stimulated cyclic AMP accumulation. HEK293 cells overexpressing wild-type D2 (WT) or D2-A4 (A4) receptors in the absence or presence of exogenous arrestin3 (arr) were incubated with 30 μM forskolin and increasing concentrations of dopamine, and cyclic AMP accumulation was determined. A, data are plotted as a percentage of forskolin-stimulated cyclic AMP accumulation in the absence of dopamine. B and C, the mean ± S.E.M. values for EC50 and maximum inhibition from four experiments are shown. (***, p < 0.001 versus wild type by paired t test). The expression levels of cell surface D2 receptors were similar in all cell lines (data not shown).

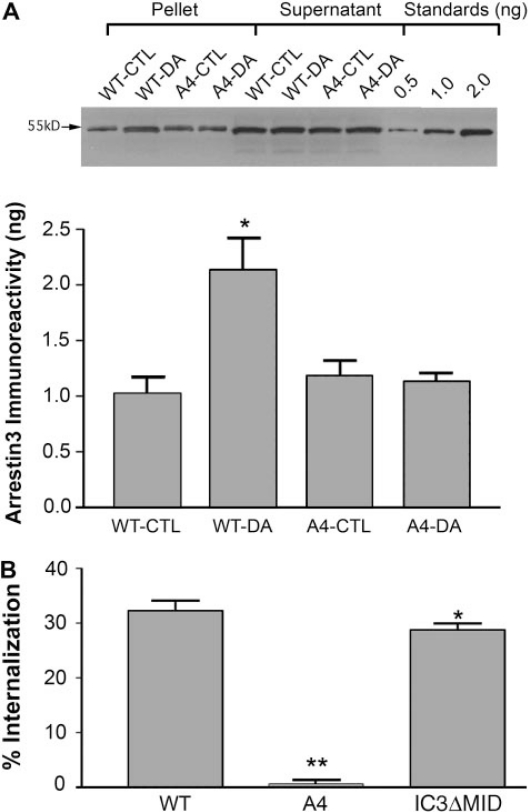

The A4 Mutation Abolished Arrestin3 Translocation and Receptor Internalization. The functional interaction of D2 and D2-A4 receptors with arrestin was evaluated by quantifying agonist-induced translocation of arrestin to the cell membrane and agonist-induced receptor internalization in HEK 293 cells transiently coexpressing wild-type or mutant D2 receptor and arrestin3. The amount of arrestin3 in the membrane fraction of cells transfected with the wild type D2 receptor was doubled from 1.0 ± 0.2 ng of arrestin3 in untreated cells to 2.1 ± 0.3 ng after treatment with 10 μM dopamine for 20 min (Fig. 7A). In contrast, in cells coexpressing D2-A4 and arrestin3, the levels of arrestin3 in the membrane preparations were equal in vehicle- and dopamine-treated cells (1.2 ± 0.1 versus 1.1 ± 0.1, respectively), indicating that the A4 mutation prevented dopamine-induced arrestin3 translocation to the plasma membrane (Fig. 7A). Neither D2 nor D2-A4 mediated detectable translocation of arrestin2 in HEK 293 cells cotransfected with arrestin2 (data not shown).

Fig. 7.

Agonist-induced translocation of arrestin3 and receptor internalization in HEK 293 cells coexpressing arrestin3 and wild type or mutant D2 receptors. A, cells were treated with 10 μM dopamine for 20 min, membranes were prepared, and levels of arrestin3 were determined by quantitative immunoblotting. Results were quantified using standard curves constructed with known amounts of purified arrestin3. The expression of cell surface receptor for the A4 mutant is similar to or higher than that for D2 wild type, as determined by intact cell [3H]sulpiride binding (data not shown). Top, an immunoblot is shown from an experiment representative of four independent experiments. Supernatants were loaded to show similar expression levels of arrestin3. Bottom, results from all four experiments are shown as the mean ± S.E.M. B, cells were treated with 10 μM dopamine for 20 min, and were subjected to the intact cell [3H]sulpiride binding assay. Results are expressed as the percentage by which the binding of [3H]sulpiride to cell surface receptors decreased after agonist stimulation, and are shown as the mean ± S.E.M. from four independent experiments (* p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01 versus wild type by paired t test). The expression levels of arrestin3 were similar in cells transfected with wild-type or mutant receptors (data not shown).

D2 receptor internalization was assessed by quantifying the agonist-induced loss of cell-surface binding of the hydrophilic ligand [3H]sulpiride in an intact cell binding assay. In cells transiently expressing the wild-type D2 receptor and arrestin3, treatment with 10 μM dopamine for 20 min decreased binding of [3H]sulpiride by 32 ± 2% (Fig. 7B). In contrast, cotransfection with arrestin2 supported little agonist-induced internalization (data not shown). Consistent with the lack of arrestin3 translocation mediated by the A4 mutant and the role of arrestin binding in D2 receptor internalization (Macey et al., 2004), the A4 mutation abolished dopamine-induced receptor internalization. In contrast, the D2-IC3ΔMID mutation (deletion of 121 residues comprising all of IC3 except the 20 residues at each terminus; see Fig. 2A) had little effect on receptor internalization (Fig. 7B). Together, these data suggest that the motif IYIV212–215 at the N terminus of the D2 receptor IC3 is required for a functional interaction between the receptor and arrestin3.

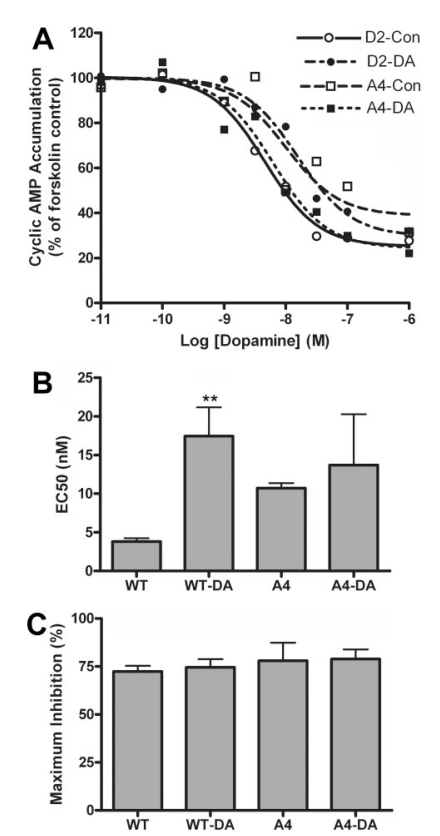

The A4 Mutation Abolished Desensitization of Cyclic AMP Accumulation. Because of the role of arrestin in desensitization of GPCRs, we evaluated the effect of the A4 mutation on dopamine-induced desensitization of D2 receptor-mediated inhibition of cyclic AMP accumulation. HEK 293 cells stably expressing wild-type or mutant D2 receptors and transiently overexpressing arrestin3 were treated with 10 μM dopamine for 20 min before measuring acute inhibition of forskolin-stimulated activity (Fig. 8). Dopamine pretreatment caused a decrease in the potency of dopamine at the wild-type D2 receptor from 3.7 nM (pEC50 = 8.43 ± 0.05) to 16 nM (pEC50 = 7.78 ± 0.09; p < 0.01), whereas the potency at the D2-A4 mutant receptor was unaffected (pEC50 = 7.97 ± 0.03 for vehicle-treated cells versus 8.12 ± 0.33 for dopamine-treated cells). Maximal inhibition of cyclic AMP accumulation was not altered by dopamine treatment, but in this set of experiments the maximal inhibition by D2-A4 was slightly but not significantly enhanced compared with wild-type D2 (Fig. 8C).

Fig. 8.

Desensitization of dopamine inhibition of forskolin-stimulated cyclic AMP accumulation. HEK293 cells stably overexpressing wild type D2 (WT) or D2-A4 (A4) receptors and transiently overexpressing arrestin3 were treated with 10 μM dopamine (DA) or vehicle (Con) for 20 min. After washing, cells were incubated with 30 μM forskolin and increasing concentrations of dopamine for 10 min, and cyclic AMP accumulation was determined. A, results from a representative experiment are plotted as a percentage of forskolin-stimulated cyclic AMP accumulation in the absence of dopamine. B and C, the mean ± S.E.M. values for EC50 and maximum inhibition from four independent experiments are shown. (**, p < 0.01 versus vehicle-treated cells by paired t test).

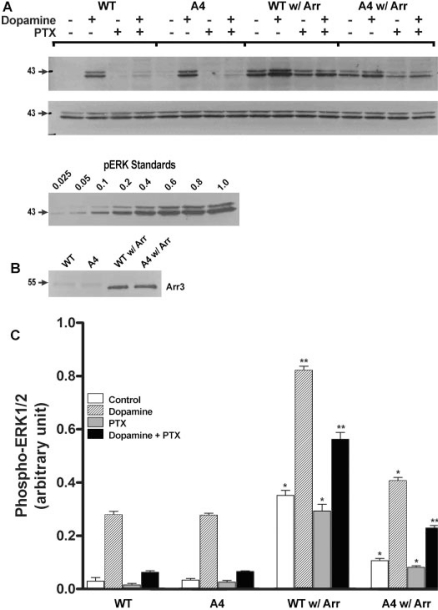

The A4 Mutation Decreased Arrestin-Dependent Activation of ERKs. Because the D2-A4 mutation abolished receptor internalization/desensitization and arrestin3 translocation, one intriguing issue is whether this mutation inhibits ERK activation. Receptor-mediated activation of ERKs (ERK1, 44 kDa; ERK2, 42 kDa) was measured by quantifying the abundance of dually phosphorylated ERKs. Treatment with dopamine induced rapid and robust activation of ERKs in HEK 293 cells expressing either the wild-type or the mutant receptor (Fig. 9). The levels of dopamine-stimulated phospho-ERKs for D2 wild-type receptor and D2-A4 receptor in the absence of overexpressed arrestin were not significantly different (Fig. 9C), which suggested that D2 receptor stimulation of ERKs in HEK 293 cells was independent of arrestin binding to the receptor in the absence of arrestin overexpression. For wild-type D2 receptor, overexpression of arrestin3 dramatically increased basal (12-fold) and dopamine-induced (2.9-fold) ERK phosphorylation, whereas for the A4 mutant, the corresponding increments were smaller (3.2- and 1.5-fold, respectively; Fig. 9, A and C). Thus, the A4 mutation decreased arrestin-dependent activation of ERKs. Similar results were observed with the D2-selective agonist quinpirole (data not shown).

Fig. 9.

Interaction of arrestin3 with the dopamine D2 receptor modulates receptor activation of ERKs. HEK293 cells overexpressing wild type D2 (WT) or D2-A4 (A4) receptors in the absence or presence of heterologously expressed arrestin3 (arr) were treated with 10 μM dopamine for 5 min before quantification of activated ERKs in cell lysates. Some cells were pretreated with PTX overnight. A, top, a representative immunoblot is shown for phospho-ERKs in lysates of cells without (CTL) or with (DA) dopamine treatment. Middle, an immunoblot shows similar expression levels of total ERKs. Bottom, an immuoblot shows that the band optical density varies linearly with the concentration of phospho-ERKs from sample WT+arr-DA. B, the expression levels of arrestin3 are shown. C, results from four independent experiments are shown as the mean ± S.E.M. (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001, versus the same drug/receptor combination without overexpressed arrestin, paired t test).

To assess the G protein-dependence of D2 receptor-mediated activation of ERKs, some cells were pretreated with pertussis toxin (PTX; 50 ng/ml overnight) before agonist treatment. This treatment regimen abolishes D2 receptor inhibition of adenylate cyclase activity and coupling to G proteins in a variety of cell lines, including HEK 293 cells (Neve et al., 1989; Watts and Neve, 1996; Watts and Neve, 1997; Watts et al., 1998). PTX treatment greatly decreased activation of ERKs by D2 and D2-A4 receptors (Fig. 9), indicating that a major component of ERK activation by the D2 receptor in HEK 293 cells requires PTX-sensitive G proteins Gαi/o. PTX treatment also decreased the activation of ERKs in cells overexpressing arrestin3, but a substantial PTX-insensitive component may be mediated by arrestin rather than Gαi/o. This PTX-insensitive and arrestin-dependent component is smaller but still present in cells expressing D2-A4, suggesting that the mutant receptor retains residual ability to bind arrestins.

Discussion

Studies of receptor-mediated translocation of GFP-tagged arrestin to the cell membrane have identified IC2 and IC3 as being particularly important for the interaction between D2-like receptors and arrestin (Kim et al., 2001). In the present study, we constructed GST fusion proteins as “bait” to identify arrestin-binding subdomains. We determined that IC3 from both D2 and D3 receptors bound arrestin3 more avidly than arrestin2. Our data also indicated that D2-IC3 and D3-IC3 bound arrestin with similar affinities; this is in contrast to the lower and different affinities of D2-IC2 and D3-IC2 for arrestin (Lan et al., 2009). Four residues at the N terminus of D2-IC3 were critical for arrestin binding. Alanine mutations of those four residues abolished D2 receptor-mediated translocation of arrestin and receptor internalization and decreased arrestin-dependent activation of ERKs, without altering receptor coupling to G proteins and the potency of agonist for inhibition of cyclic AMP accumulation, suggesting that the D2-A4 mutant is a receptor that is biased toward G protein-mediated signaling pathways and away from arrestin-dependent pathways.

Accumulating evidence suggests that multiple mechanisms contribute to GPCR-arrestin interactions. Phosphorylation of receptor intracellular domains by GRKs may promote arrestin binding as a result of electrostatic interactions between negatively charged phosphates on the receptor and positively charged arrestin residues that serve as a phosphorylation sensor (Gurevich and Gurevich, 2006). These electrostatic interactions may also induce a conformational change in arrestin that enhances its binding to the receptor (Gurevich and Gurevich, 2004). Phosphorylation of the receptor may also contribute indirectly to arrestin binding by initiating conformational changes of the intracellular domains that expose binding sites for arrestin (Kim et al., 2004). Receptor activation is also accompanied by conformational changes, exposing receptor sites that interact with a proposed activation sensor in arrestin (Gurevich and Gurevich, 2006). Because the GST fusion proteins are not phosphorylated, this method does not identify receptor phosphorylation sites that bind arrestin but identifies only determinants of binding that are revealed by activation- or phosphorylation-dependent conformational changes of the receptor intracellular domains; the determinants are presumably occluded in the inactive and/or unphosphorylated full-length receptor but exposed when the receptor fragments are expressed as GST fusion proteins, free from constraints imposed by other domains of the intact receptor. Thus, this in vitro binding assay may identify both phosphorylation-independent and some phosphorylation-dependent determinants of the interaction between receptor and arrestin.

Arrestin-binding domains/residues vary among GPCRs, based on results from binding studies with purified arrestins along with recombinant or synthetic peptides representing receptor intracellular fragments. Both arrestin2 and arrestin3 bind to IC3 of the 5-HT2A receptor and the δ-opioid receptor, and to the C-terminal domain of δ- and κ-opioid receptors, with certain serine/threonine residues in these receptor regions being important for binding (Gelber et al., 1999; Cen et al., 2001). Binding of arrestin2 to the M3-muscarinic receptor requires both N- and C-terminal regions of the IC3 of the M3-muscarinic receptor subdomains, whereas for arrestin3, the C-terminal region of the IC3 is sufficient for binding (Wu et al., 1997). Attempts to define more precisely nonphosphorylated residues that are sites of arrestin binding have identified the highly conserved DRY sequence at the N terminus of IC2 (Huttenrauch et al., 2002), an aspartate residue in IC3 of the luteinizing hormone/choriogonadotropin receptor that is thought to mimic a phosphorylated residue (Mukherjee et al., 2002), and BXXBB (B = basic residue, X = any) motifs present in the N- and C-terminal portions of IC3 of the α2-adrenoceptors (DeGraff et al., 2002). Our studies of basic residues in similar locations in the D2 receptor suggest that they are not involved in the binding of arrestin3 to this receptor (H. Lan and K. Neve, unpublished observations).

Our GST pull-down studies demonstrated the ability of D2-like receptor IC3 to bind arrestin3 with high-affinity (Kd = 70–80 nM). These values are lower (i.e., higher affinity) than the micromolar affinities derived from surface plasmon resonance studies (Cen et al., 2001; Liu et al., 2004), closer to the subnanomolar affinity of arrestin for the intact phosphorylated active receptors (Gurevich et al., 1995), and consistent with estimates of arrestin concentrations in neurons (30–200 nM) (Gurevich et al., 2004), suggesting that arrestin affinities for the receptor loops are biologically relevant. Consistent with the view that stronger agonist-induced phosphorylation of the D2 receptor than of the D3 receptor contributes to differential patterns of translocation of arrestin to cell membrane (Kim et al., 2001), we observed that arrestin bound with equal affinity to nonphosphorylated IC3 from both receptors.

Studies with full-length receptors have used direct binding of arrestin, arrestin translocation, and receptor internalization as assays to explore receptor determinants of arrestin binding (Gurevich and Gurevich, 2006), although with these assays it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between phosphorylated or nonphosphorylated determinants of binding. These approaches revealed that receptor elements involved in arrestin binding can be localized almost anywhere on the intracellular surface of the receptor, including in the C-terminal tail (Qian et al., 2001), IC3 (Lee et al., 2000; Kim et al., 2001; DeGraff et al., 2002; Namkung and Sibley, 2004), IC2 (Raman et al., 1999; Kim et al., 2001), and IC1 (Raman et al., 1999; Kishi et al., 2002). The present work describes a significant nonphosphorylated determinant of arrestin binding at the N terminus of D2-IC3.

The predominant pathway for GPCR endocytosis/internalization involves arrestin-dependent recruitment into clathrin-coated vesicles (Ferguson, 2001). A number of motifs have been proposed to be required for receptor endocytosis, including NP(X2,3)Y, DRYXXV/IXXPL, BXXBB, and a dileucine motif, all located within or close to the transmembrane proximal domains of IC2, IC3, and the carboxyl terminus of GPCRs (Barak et al., 1994; Moro et al., 1994; Arora et al., 1995; Gabilondo et al., 1997; DeGraff et al., 2002). It is noteworthy that a membrane-proximal YXXϕ motif, where ϕ is any bulky hydrophobic residue, was reported to interact with μ2 subunit of the AP2 complex and to be important for clathrin-mediated endocytosis of many integral membrane proteins (Ohno et al., 1995; Boll et al., 1996; Owen and Evans, 1998; Collins et al., 2002; Royle et al., 2005; Vogt et al., 2005). In our study, via GST pull-down assays, we identified the 5-residue sequence IYIVL at the N terminus of D2-IC3 that incorporates the YXXϕ motif and that is required for high-affinity binding of arrestin. Mutation of four of these residues to alanine in the full-length receptor (D2-A4) prevented D2 receptor-mediated translocation of arrestin to the membrane, agonist-induced receptor internalization, and desensitization of cyclic AMP accumulation associated with overexpression of arrestin, indicating that this sequence is required for a functional interaction between the D2 receptor and arrestin. It is noteworthy that the A4 mutation did not alter either high-affinity binding of dopamine to the D2 receptor or the potency of dopamine for D2-mediated inhibition of cyclic AMP accumulation, suggesting that coupling of the mutant receptor to G proteins and the activation of G proteins were not affected by the mutation; thus, distinct structural determinants of the D2 receptor mediate its interactions with arrestins and G proteins.

The lack of evidence for binding of arrestin2 to the D2 receptor is surprising in light of an earlier publication from this laboratory reporting that the D2 receptor preferentially interacts with arrestin2 over arrestin3 in neostriatal neurons (Macey et al., 2004). Much of the discrepancy could potentially be explained by the type of cell in which the receptor is expressed. In the earlier publication, it was reported that the preferential interaction with arrestin2 was observed in neostriatal neurons, but not in NS20Y neuroblastoma cells, and it was concluded that the preferential interaction with arrestin2 in neurons was related to compartmentalization of the receptor, arrestins, or other interacting proteins rather than to an inherent preference for arrestin3. The preferential interaction with arrestin3 in HEK293 cells may be due to the influence of similar cell type-dependent factors. In addition, the preference for arrestin3 described here is consistent with work indicating that arrestin3, but not arrestin2, mediates D2 receptor inhibition of the protein kinase Akt and methamphetamine-induced locomotor activity (Beaulieu et al., 2005).

As a signaling-biased GPCR, capable of activating G protein-regulated signaling pathways but with reduced ability to bind arrestin, the D2-A4 mutant receptor is a useful experimental tool. Stimulation of some GPCRs induces the assembly of a protein complex in which arrestin acts as a receptor-regulated scaffold, recruiting mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades to the agonist-occupied GPCR and facilitating GPCR-dependent kinase activation (Luttrell et al., 1999; McDonald et al., 2000). That the D2 receptor-mediated activation of ERKs was not affected by the A4 mutation but almost entirely prevented by PTX in HEK 293 cells indicates that when the abundance of arrestins is low, D2 receptor activation of ERKs is independent of arrestin binding to the receptor and mediated predominantly by PTX-sensitive G proteins. In contrast, over-expression of arrestin3 greatly increased the D2 receptor-mediated activation of ERKs, in particular enhancing a PTX-insensitive component of ERK activation, but had a much smaller effect in cells expressing the arrestin-insensitive mutant D2-A4. Likewise, parathyroid hormone receptor-mediated activation of ERK in HEK 293 cells is composed of distinct arrestin- and G protein-dependent pathways (Gesty-Palmer et al., 2006).

Arrestin3 is also a scaffold for Akt and protein phosphatase 2A, and disruption of signaling through this protein complex reduces dopamine-dependent behaviors in mice (Beaulieu et al., 2005). If arrestin3 binding to the D2 receptor is required for activation of this signaling pathway, we predict that the D2-A4 mutant would also be deficient in signaling via Akt. The use of arrestin3-null mutant mice is one way in which investigators have differentiated between G protein- and arrestin-dependent responses to receptor activation (Beaulieu et al., 2005; Raehal et al., 2005); the use of arrestin-insensitive mutant receptors represents an alternative approach.

ABBREVIATIONS:

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor; GRK, G protein-coupled receptor kinase

- GST

glutathione transferase

- HEK

human embryonic kidney

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- D2-A4

IYIV212–215A4 mutant of the rat dopamine D2L receptor

- IC3

third intracellular loop of a GPCR

- D2-IC3

third intracellular loop of the rat dopamine D2L receptor

- D3-IC3

third intracellular loop of the rat dopamine D3 receptor

- PVDF

polyvinylidene difluoride

- TBS

Tris-buffered saline

- CMF-PBS

calcium- and magnesium-free phosphate-buffered saline

- CHAPS

3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate

- TBST

Tris-buffered saline/Tween 20

- PTX

pertussis toxin

Footnotes

This work was supported by United States Public Health Service grants MH045372 (to K.A.N.), GM077561 (to V.V.G.), and EY011500 (to V.V.G.), and the VA Merit Review and Career Scientist programs (to K.A.N.).

This article is a companion to “An Intracellular Loop 2 Amino Acid Residue Determines Differential Binding of Arrestin to the Dopamine D2 and D3 Receptors,” by Lan H, Teeter MM, Gurevich VV, and Neve KA on page 19 of this issue. That article should have been printed immediately following this article.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

References

- Arora KK, Sakai A, Catt KJ. Effects of second intracellular loop mutations on signal transduction and internalization of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:22820–22826. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.39.22820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barak LS, Tiberi M, Freedman NJ, Kwatra MM, Lefkowitz RJ, Caron MG. A highly conserved tyrosine residue in G protein-coupled receptors is required for agonist-mediated β2-adrenergic receptor sequestration. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:2790–2795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu JM, Sotnikova TD, Marion S, Lefkowitz RJ, Gainetdinov RR, Caron MG. An Akt/β-arrestin 2/PP2A signaling complex mediates dopaminergic neurotransmission and behavior. Cell. 2005;122:261–273. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boll W, Ohno H, Songyang Z, Rapoport I, Cantley LC, Bonifacino JS, Kirchhausen T. Sequence requirements for the recognition of tyrosine-based endocytic signals by clathrin AP-2 complexes. EMBO J. 1996;15:5789–5795. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cen B, Xiong Y, Ma L, Pei G. Direct and differential interaction of β-arrestins with the intracellular domains of different opioid receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59:758–764. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.4.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Prusoff WH. Relationship between the inhibition constant (K1) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem Pharmacol. 1973;22:3099–3108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins BM, McCoy AJ, Kent HM, Evans PR, Owen DJ. Molecular architecture and functional model of the endocytic AP2 complex. Cell. 2002;109:523–535. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00735-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGraff JL, Gurevich VV, Benovic JL. The third intracellular loop of α2-adrenergic receptors determines subtype specificity of arrestin interaction. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:43247–43252. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207495200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SSG. Evolving concepts in G protein-coupled receptor endocytosis: the role in receptor desensitization and signaling. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabilondo AM, Hegler J, Krasel C, Boivin-Jahns V, Hein L, Lohse MJ. A dileucine motif in the C terminus of the β2-adrenergic receptor is involved in receptor internalization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12285–12290. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelber EI, Kroeze WK, Willins DL, Gray JA, Sinar CA, Hyde EG, Gurevich V, Benovic J, Roth BL. Structure and function of the third intracellular loop of the 5-hydroxytryptamine2A receptor: the third intracellular loop is α-helical and binds purified arrestins. J Neurochem. 1999;72:2206–2214. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0722206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gesty-Palmer D, Chen M, Reiter E, Ahn S, Nelson CD, Wang S, Eckhardt AE, Cowan CL, Spurney RF, Luttrell LM, et al. Distinct β-arrestin- and G protein-dependent pathways for parathyroid hormone receptor-stimulated ERK1/2 activation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:10856–10864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513380200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurevich EV, Benovic JL, Gurevich VV. Arrestin2 expression selectively increases during neural differentiation. J Neurochem. 2004;91:1404–1416. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurevich VV, Dion SB, Onorato JJ, Ptasienski J, Kim CM, Sterne-Marr R, Hosey MM, Benovic JL. Arrestin interactions with G protein-coupled receptors. Direct binding studies of wild type and mutant arrestins with rhodopsin, β2-adrenergic, and m2 muscarinic cholinergic receptors. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:720–731. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.2.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurevich VV, Gurevich EV. The molecular acrobatics of arrestin activation. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2004;25:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurevich VV, Gurevich EV. The structural basis of arrestin-mediated regulation of G-protein-coupled receptors. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;110:465–502. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han M, Gurevich VV, Vishnivetskiy SA, Sigler PB, Schubert C. Crystal structure of β-arrestin at 1.9 Å: possible mechanism of receptor binding and membrane translocation. Struct Fold Des. 2001;9:869–880. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00644-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttenrauch F, Nitzki A, Lin FT, Höning S, Oppermann M. β-arrestin binding to CC chemokine receptor 5 requires multiple C-terminal receptor phosphorylation sites and involves a conserved Asp-Arg-Tyr sequence motif. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:30769–30777. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204033200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itokawa M, Toru M, Ito K, Tsuga H, Kameyama K, Haga T, Arinami T, Hamaguchi H. Sequestration of the short and long isoforms of dopamine D2 receptors expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;49:560–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KM, Valenzano KJ, Robinson SR, Yao WD, Barak LS, Caron MG. Differential regulation of the dopamine D2 and D3 receptors by G protein-coupled receptor kinases and β-arrestins. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:37409–37414. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106728200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim OJ, Gardner BR, Williams DB, Marinec PS, Cabrera DM, Peters JD, Mak CC, Kim KM, Sibley DR. The role of phosphorylation in D1 dopamine receptor desensitization: evidence for a novel mechanism of arrestin association. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:7999–8010. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308281200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishi H, Krishnamurthy H, Galet C, Bhaskaran RS, Ascoli M. Identification of a short linear sequence present in the C-terminal tail of the rat follitropin receptor that modulates arrestin-3 binding in a phosphorylation-independent fashion. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:21939–21946. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110894200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan H, Teeter MM, Gurevich VV, Neve KA. An intracellular loop 2 amino acid residue determines differential binding of arrestin to the dopamine D2 and D3 receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;75:19–26. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.050542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KB, Ptasienski JA, Pals-Rylaarsdam R, Gurevich VV, Hosey MM. Arrestin binding to the M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor is precluded by an inhibitory element in the third intracellular loop of the receptor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9284–9289. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P, Roush ED, Bruno J, Osawa S, Weiss ER. Direct binding of visual arrestin to a rhodopsin carboxyl terminal synthetic phosphopeptide. Mol Vis. 2004;10:712–719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Buck DC, Macey TA, Lan H, Neve KA. Evidence that calmodulin binding to the dopamine D2 receptor enhances receptor signaling. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2007;27:47–65. doi: 10.1080/10799890601094152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luttrell LM, Ferguson SS, Daaka Y, Miller WE, Maudsley S, Della Rocca GJ, Lin F, Kawakatsu H, Owada K, Luttrell DK, et al. β-arrestin-dependent formation of β2 adrenergic receptor Src protein kinase complexes. Science. 1999;283:655–661. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5402.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macey TA, Gurevich VV, Neve KA. Preferential interaction between the dopamine D2 receptor and arrestin2 in neostriatal neurons. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;66:1635–1642. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.001495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macey TA, Liu Y, Gurevich VV, Neve KA. Dopamine D1 receptor interaction with arrestin3 in neostriatal neurons. J Neurochem. 2005;93:128–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarova O, Kamberov E, Margolis B. Generation of deletion and point mutations with one primer in a single cloning step. Biotechniques. 2000;29:970–972. doi: 10.2144/00295bm08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald PH, Chow CW, Miller WE, Laporte SA, Field ME, Lin FT, Davis RJ, Lefkowitz RJ. β-Arrestin 2: a receptor-regulated MAPK scaffold for the activation of JNK3. Science. 2000;290:1574–1577. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5496.1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moro O, Shockley MS, Lameh J, Sadée W. Overlapping multi-site domains of the muscarinic cholinergic Hm1 receptor involved in signal transduction and sequestration. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:6651–6655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S, Gurevich VV, Preninger A, Hamm HE, Bader MF, Fazleabas AT, Birnbaumer L, Hunzicker-Dunn M. Aspartic acid 564 in the third cytoplasmic loop of the luteinizing hormone/choriogonadotropin receptor is crucial for phosphorylation-independent interaction with arrestin2. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:17916–17927. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110479200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namkung Y, Sibley DR. Protein kinase C mediates phosphorylation, desensitization, and trafficking of the D2 dopamine receptor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:49533–49541. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408319200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neve KA, Henningsen RA, Bunzow JR, Civelli O. Functional characterization of a rat dopamine D-2 receptor cDNA expressed in a mammalian cell line. Mol Pharmacol. 1989;36:446–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neve KA, Seamans JK, Trantham-Davidson H. Dopamine receptor signaling. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2004;24:165–205. doi: 10.1081/rrs-200029981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno H, Stewart J, Fournier MC, Bosshart H, Rhee I, Miyatake S, Saito T, Gallusser A, Kirchhausen T, Bonifacino JS. Interaction of tyrosine-based sorting signals with clathrin-associated proteins. Science. 1995;269:1872–1875. doi: 10.1126/science.7569928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen DJ, Evans PR. A structural explanation for the recognition of tyrosine-based endocytotic signals. Science. 1998;282:1327–1332. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5392.1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce KL, Lefkowitz RJ. Classical and new roles of β-arrestins in the regulation of G-protein-coupled receptors. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:727–733. doi: 10.1038/35094577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian H, Pipolo L, Thomas WG. Association of β-arrestin 1 with the type 1A angiotensin II receptor involves phosphorylation of the receptor carboxyl terminus and correlates with receptor internalization. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:1706–1719. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.10.0714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raehal KM, Walker JK, Bohn LM. Morphine side effects in β-arrestin 2 knockout mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314:1195–1201. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.087254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raman D, Osawa S, Weiss ER. Binding of arrestin to cytoplasmic loop mutants of bovine rhodopsin. Biochemistry. 1999;38:5117–5123. doi: 10.1021/bi9824588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royle SJ, Qureshi OS, Bobanović LK, Evans PR, Owen DJ, Murrell-Lagnado RD. Non-canonical YXXGϕ endocytic motifs: recognition by AP2 and preferential utilization in P2X4 receptors. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:3073–3080. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt C, Eickmann M, Diederich S, Moll M, Maisner A. Endocytosis of the Nipah virus glycoproteins. J Virol. 2005;79:3865–3872. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.6.3865-3872.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts VJ, Neve KA. Sensitization of endogenous and recombinant adenylate cyclase by activation of D2 dopamine receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;50:966–976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts VJ, Neve KA. Activation of type II adenylate cyclase by D2 and D4 but not D3 dopamine receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;52:181–186. doi: 10.1124/mol.52.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts VJ, Wiens BL, Cumbay MG, Vu MN, Neve RL, Neve KA. Selective activation of Gαo by D2L dopamine receptors in NS20Y neuroblastoma cells. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8692–8699. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-21-08692.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, Krupnick JG, Benovic JL, Lanier SM. Interaction of arrestins with intracellular domains of muscarinic and α2-adrenergic receptors. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17836–17842. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.28.17836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]