Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the accuracy and agreement of International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury (ISCSCI) classification and to determine the effectiveness of formal training for pediatric clinicians.

Study Population:

Participants (N = 28) in a formal 90-minute classification training session.

Outcome Measure:

Pre/post-training examination of 10 case examples of a variety of neurological classifications.

Results:

Regardless of years of experience with the ISCSCI, a statistically significant improvement (P < 0.05) in classification was achieved after formal training. Before training, 27% (539 of 1,960) of the questions were answered incorrectly. After training, the percentage of incorrect classifications decreased to 11% (198 of 1,960) incorrect (P < 0.05). After training, the percentage of incorrect motor level classifications decreased by 23% (42% to 19% incorrect; P < 0.05). Post-training improvements were also demonstrated (P < 0.05) in classifying sensory levels (9% to 3% incorrect), neurological levels (31% to 6% incorrect), and severity of injury (9% to 0% incorrect). After training, reductions in classification errors (P < 0.05) were demonstrated in American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) Impairment Scale (AIS) A (from 20% to 7%), B (50% to 11%), C (71% to 46%), and D (63% to 16%).

Conclusions:

This study demonstrated the benefits of formal, standardized training for accurate classification of the ISCSCI. Effective training programs must emphasize the guidelines and decision algorithms used to determine motor level and ASIA AIS designations because these remained problematic after training and are often a concern of patients/parents and are primary endpoints in clinical trials for neurological recovery.

Keywords: Spinal cord injuries; Physical examination, neurological; International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury; American Spinal Injury Association

INTRODUCTION

American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) has published the International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury (ISCSCI) as the recommended practice guideline for evaluating and classifying the neurological impairment of spinal cord injury (SCI) (1). With the exception of our work (2–5), the utility of the ISCSCI has not been studied in children; the psychometric studies leading to the most recent version of the ISCSCI (1) were studies of adults only (6–14). Although the original intent of the ISCSCI was to standardize the neurological examination of persons with acute injuries and for purposes of clinical comparisons, the ISCSCI is now also used as a primary outcome measure for research studies and clinical trials (15–21). In an effort to standardize the neurological examination and classification of SCI in children and in anticipation of additional clinical trials for neurological recovery (particularly those that include children and youth), our research center has been conducting studies to establish the utility of the ISCSCI in the pediatric population (2–5).

This study is part of our larger effort and reports on the agreement of classification of SCI in children before and after formal training in the ISCSCI classification system. The significance of the work is threefold. First, prior to inclusion of children in clinical trials and other outcomes research, there is a need for a valid outcome measure that is capable of generating reliable motor and sensory scores from children and one that, preferably, is similar to that used with adults to allow for comparison of outcomes. Second, there is a need for a measure that is capable of measuring small and meaningful neurological changes in children. Third, and the topic of this paper, is the need for a standardized classification system that is consistently applied across children and health care systems. Thus, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the accuracy and agreement of ISCSCI classification of SCI based on ISCSCI motor and sensory scores and to determine the effectiveness of formal training on pediatric clinicians' accuracy of classifying an injury based on the ISCSCI.

METHODS

As part of a larger multicenter study to evaluate the utility and agreement of the ISCSCI in children and youth, formal training in the examination of the motor and sensory examinations and classification of the injury was conducted for all investigators and research assistants involved in the study. The results of the training in examination have been published elsewhere (3).

For this study, which focused entirely on classification, there were 28 pediatric professionals separated into 5 groups: 11 physical therapists, 6 occupational therapists, 3 physicians, 4 allied health professionals (1 nurse, 2 nurse practitioners, 2 physician assistants), 2 research associates (1 research engineer and 1 research assistant), and 2 student therapists. Actual experience with the ISCSCI classification system varied greatly. Collectively, the 28 participants reported that they had classified an average of 59 injuries based on ISCSCI examinations (range = 0–500). They were divided into 3 groups by experience in classifying examinations: (a) no experience, having scored from 0 to 9 examinations in the past (n = 14), (b) novices, having scored from 10 to 29 examinations in the past (n = 3), (c) experts, having scored 30 or more examinations in the past (n = 11).

Training Session

The senior investigator of the multicenter study conducted the formal training based on the most recent ISCSCI standards, which are considered the gold standard for neurological classification of patients with SCI (1). In addition to a review of the terminology and guidelines set forth in the standards manual (1), common errors in classification and “rules” to avoid such errors were also presented. The latter information was based largely on material provided at an instructional course given by Steven Kirshblum, MD, at the 2006 American Paraplegia Society Meeting, entitled, “Difficult Cases in Classification of SCI” (22). This 90-minute educational session included a formal presentation, didactics, case reviews, and discussion.

Outcome Measure

Prior to formal training, participants were provided with the results of motor and sensory examinations and anorectal examinations of 10 hypothetical persons with SCI. For each of the 10 ISCSCI forms, participants were asked to classify motor level (right and left), sensory level (right and left), neurological level, severity of injury (complete vs incomplete), and ASIA Impairment Scale (AIS). Participants were not given options but were required to “fill in the missing space.” For example, the participant had to record the exact neurological level. If the participant recorded a neurological level for the right side and a separate one for the left side, this was considered an incorrect answer. Among the 10 sample examinations, there were 4 incomplete cervical injuries (3 with AIS C and 1 with AIS D), 2 complete cervical injuries (AIS A), 2 sensory incomplete thoracic or lumbar level injuries (AIS B), 1 motor incomplete thoracic (AIS C), and 1 complete thoracic injury (AIS A). One examination included a non-key muscle, which was important to identify in order to distinguish AIS B from AIS C injuries. In total, each rater completed 70 questions, ie, 10 case examples with each case having 7 test questions (left/right sensory, left/right motor, neurological level, severity of injury [complete/incomplete], and AIS classification), resulting in a total of 1,960 questions for before-after training comparison.

Data Management and Analysis

Before and after formal training, for each of the 10 ISCSCI, the 28 raters classified left and right motor and sensory scores, motor level, sensory level, neurological level, severity of injury (complete vs incomplete), and AIS classification. Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate the effect of training on correctly classifying the SCI. Paired t tests were used to compare the mean of pretest scores with post-test scores. The Spearman rho was used to evaluate the relationship between scoring examinations and scores before training. All data were entered into Microsoft Access for computerized scoring. Descriptive analysis was completed using SPSS (v 14), and SAS (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) was used to conduct the repeated measure ANOVA.

RESULTS

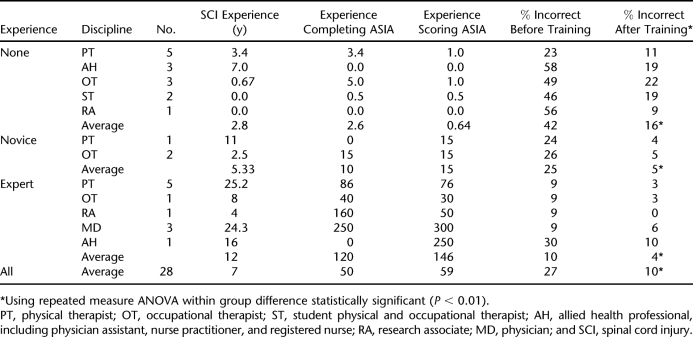

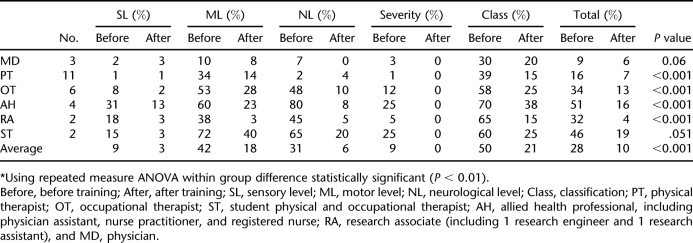

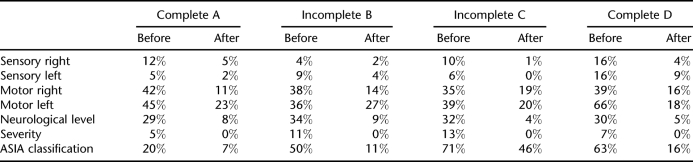

Before training, 27% (539 of 1,960) of the questions were answered incorrectly (Table 1). Previous experience with classification of ISCSCI examinations was positively correlated (P < 0.05, r2 = 0.50) with higher pretraining scores. After training, the average percentage of incorrect classifications decreased from 27% to 10% (198 of 1,960 incorrect) (P < 0.05). Grouping by number of ISCSCI scoring experience, a statistically significant improvement (P < 0.05) in classification was achieved after formal training (Table 1). When grouped by types of disciplines, physicians (n = 3) had the least incorrect answers at 9% before the training session (Table 2). After training, the percentage of all health care providers' incorrect classifications decreased from 28% to 10% (P < 0.05). Physicians, physical therapists, and research assistants had the fewest incorrect classifications after training. Motor level and AIS designation were the 2 factors with the highest percentages of incorrect classifications both before and after training (Table 2). After training, the percentage of incorrect motor level classifications decreased by 24% (42% to 18% incorrect P < 0.05) and incorrect AIS classifications decreased by 29% (from 50% to 21%, P < 0.05). Post-training improvements were also demonstrated (P < 0.05) in reducing incorrect sensory levels (9% to 3%), neurological levels (31% to 6%), and severity of injury (9% to 0%). After training, improvements (P < 0.05) were demonstrated in AIS classifications. For example, before training, 20% of all classifications completed by all 28 participants of cases that were actually AIS A were incorrect (Table 3). After training, this was reduced to only 7% incorrect. Likewise, reductions in incorrect answers were also noted for AIS Bs (from 50% to 11%), Cs (from 71% to 46%), and Ds (from 63% to 16%). Although improvements in all AIS classifications were evident, a persistently high number (46%) of incorrect designations of AIS C remained after training.

Table 1.

Description and Examination Scores of Pediatric Providers

Table 2.

Percentage of Incorrect Answers by Discipline of Pediatric Provider by Section of the International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury

Table 3.

Percentage of Incorrect Answers Before and After Training by Classification of Injury

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated the effectiveness of formal training in classification of the 2002 ISCSCI. In this study, the percent of incorrect classifications on all variables decreased (sensory level, motor level, neurological level, injury type, and AIS). Before training, there was a clear indirect relationship between having SCI experience and having experience with ISCSCI and having fewer incorrect answers. In this study, all participants, regardless of experience with the ISCSCI classification, improved. Those considered expert participants decreased their incorrect classifications from 10% to 4%. After training, the novice (previously scored 10–29 examinations) participants' decreased their incorrect classifications from 25% to 5%. Finally, those classified as having no experience (previously scored 0–9 examinations) decreased their incorrect classifications from 42% to 16%. Although all groups improved, experts (scored 30 or more examinations) and novices improved to the point of having less than 5% incorrect answers. The improvement across all experience levels demonstrates that training in the ISCSCI classification schema can decrease the frequency of incorrect designations of motor level, sensory level, neurological level, and AIS, regardless of prior experience.

The issue of professional background is an important one, particularly as it is related to data collection protocols for clinical trials. Only 3 physicians participated in the training, and all 3 were considered experts. Among the expert nonphysicians, scores before and after training were essentially the same as those of the physicians (Table 1). In this study, expert nonphysicians were physical and occupational therapists and a research assistant, all of whom had collected ISCSCI data for several research studies, including Proneuron's clinical trial. After training, 2 of these expert nonphysicians classified every ISCSCI examination correctly. This suggests that with sufficient experience and appropriate training, accurate classification of ISCSCI examinations is obtainable for ancillary health care providers. The implication of this finding is an important one when one considers the costs associated with clinical trial data collection and the demands placed upon busy physicians who may be unable to carry out such data collection protocols due to time constraints. To have a deeper understanding of the relationship between scoring examinations and professional disciplines, future studies should include a larger sample of disciplines with varying levels of experience with ISCSCI.

Importantly, after training, the greatest improvement was in classifying the injury as complete or incomplete. Before training, 9% of examinations had severity of injury incorrectly classified. After training, none of the examinations was classified incorrectly for severity.

Unfortunately, even after training, accurate classification of motor level and AIS designation remained unacceptably low. After training, incorrect classification of motor level was reduced from 42% to 18%; although the improvement is notable, 18% is likely to be unacceptably high for clinical trials and outcomes research. Importantly, correct classification of the AIS designation, which is an important classification for clinical trials that target neurological recovery, is dependent upon correct classification of the motor level. After training, incorrect AIS classification was lowered from 50% incorrect designations to 21%. Although this reduction demonstrated effectiveness of the training, only 5 of the 27 (19%) raters were able to correctly classify all 10 test examples. Classifying examinations of individuals with motor incomplete injuries represent the greatest challenges for raters. After training, 46% of the AIS C examinations were incorrectly classified (Table 3). Two primary reasons exist for the incorrect classifications of AIS C examinations. First, raters neglected to consider non-key muscles in classification decisions, and second, raters did not apply the manual's guidelines for decision making between AIS B and AIS C when motor preservation occurred more than 3 levels below the motor level (1). Formal training programs must highlight these details because they remain pivotal in accurate classification. Furthermore, this study only examined the immediate benefits of a training program. In the future, training programs should include a second examination several weeks to months after training to ensure the long-term success of training.

Our results support previous studies that suggest training in the ISCSCI classification of the neurological consequence is required; once implemented, the training can be effective in reducing the errors that commonly occur when classifying SCI. In 1991, Priebe asked 15 house officers and physicians to score 5 case studies using the standards established in 1989 (6). After the pretest, participants were given training sessions and retested 2 months later; post-test results demonstrated improvement in accurate examination and classification. Even in 1991, the need was recognized for a formal training mechanism to improve the reliability of the standards when used by clinicians and researchers. A follow-up paper by Cohen et al (23) reported improvements in the ISCSCI after training of 106 professionals who participated in an instructional course at the 1992 ASIA meeting. Their work was limited by the presentation of only 2 case examples but contributed to the notions that the ISCSCI requires attention to detail and that those who employ it may benefit from formal training.

CONCLUSIONS

Although previous studies have not focused on pediatrics, the results of this study suggest that for pediatric providers, standard training may be essential to the accurate classification of the neurological consequence of SCI using the ISCSCI, regardless of their experience in SCI. Effective training programs must emphasize the guidelines and decision algorithms used to determine motor level and AIS designations. These 2 classifications, which remained problematic after training, are often a concern of patients and parents and primary endpoints in clinical trials for neurological recovery. Currently, the ASIA Standards community is working on a computer program to reduce or eliminate the confusion associated with scoring examinations.

References

- American Spinal Injury Association. Reference Manual of the International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury. Chicago, IL: American Spinal Injury Association; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mulcahey MJ, Gaughan J, Chafetz R, Betz RR, Vogel LC. Testing a limited number of dermatomes (ASIAQUICK) as predictor of the 56 dermatome score [abstract P25] J Spinal Cord Med. 2007;30:408. [Google Scholar]

- Mulcahey MJ, Gaughan J, Betz RR, Vogel LC.Rater agreement on the ISCSCI motor and sensory scores obtained before and after formal training in testing technique J Spinal Cord Med. 200730 (suppl 1) S146–S149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulcahey MJ, Gaughan J, Betz RR, Johansen KJ. The International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury: reliability of data when applied to children and youths. Spinal Cord. 2007;45:452–459. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101987. Epub. October 3, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulcahey MJ, Gaughan J, Betz R. Agreement of motor and sensory scores at individual myotomes and dermatomes in persons with complete spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. Epub June 10, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Priebe MP, Waring WP. The interobserver reliability of the revised American Spinal Injury Association standards for neurological classification of spinal injury patients. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1991;70:268–270. doi: 10.1097/00002060-199110000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan W, Wilkerson MA, Rossi D, Mechoulam F, Frankowski RF. A test of the ASIA guidelines for classification of spinal cord injuries. J Neurol Rehabil. 1990;4:39–53. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen ME, Ditunno JF, Jr, Donovan WH, Maynard FM., Jr A test of the 1992 International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury. Spinal Cord. 1998;36:554–560. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen ME, Bartko J. Reliability of ISCSCI-92 for neurological classification of spinal cord injury. In: Ditunno JF, Donovan WH, Maynard FM, editors. Reference Manual for the International Standards for Neurological and Functional Classification of Spinal Cord Injury. Chicago, IL: American Spinal Injury Association; 1994. pp. 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Marino RJ, Graves DE. Metric properties of the ASIA motor score: subscales improve correlation with functional activities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:1804–1810. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino RJ, Jones LM, Kirshblum SC, Tal J. Reliability of the ASIA motor and sensory examination [abstract P43] J Spinal Cord Med. 2004;27:194. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2008.11760707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard FM, Jr, Bracken MB, Creasey G, et al. International Standards for Neurological and Functional Classification of Spinal Cord Injury. Spinal Cord. 1997;35:266–274. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson M, Tollback A, Gonzales H, Borg J. Inter-rater reliability of the 1992 International Standards for Neurological and Functional Classification of Spinal Cord Injury. Spinal Cord. 2000;38:675–679. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen ME, Sheehan T, Herbison G. Content validity and reliability of the International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 1996;1:15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Baptiste DC, Fehlings MG. Pharmacological approaches to repair the injured spinal cord. J Neurotrauma. 2006;23:318–334. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown PJ, Marino RJ, Herbison GJ, Ditunno JF., Jr The 72-hour examination as a predictor of recovery in motor complete quadriplegia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1991;72:546–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaustein DM, Zafonte R, Thomas D, Herbison GJ, Ditunno JF. Predicting recovery of motor complete quadriplegic patients: 24 hour v 72 hour motor index scores. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1993;72:306–311. doi: 10.1097/00002060-199310000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JW, Becker D, Sadowsky CL, Jane JA, Sr, Conturo TE, Schultz LM.Late recovery following spinal cord injury: case report and review of the literature J Neurosurg. 200297 (suppl 2) 252–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracken MB, Shepard MJ, Collins WF, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of methylprednisolone or naloxone in the treatment of acute spinal-cord injury: results of the Second National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1405–1411. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199005173222001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracken MB.Treatment of acute spinal cord injury with methylprednisolone: results of a multicenter, randomized clinical trial J Neurotrauma. 19918 (suppl 1) S47–S50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracken MB.Methylprednisolone and acute spinal cord injury: an update of the randomized evidence Spine. 200126 (suppl 24) S47–S54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirshblum SC. Difficult cases in classification of SCI; Presented at: American Paraplegia Society Meeting; September 5, 2006;; Las Vegas, NV: [Google Scholar]

- Cohen ME, Ditunno JF, Jr, Donovan WH, Maynard FM., Jr A test of the 1992 International Standards for Neurological and Functional Classification of Spinal Cord Injury. Spinal Cord. 1998;36:554–560. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]