Abstract

Listeria monocytogenes is responsible for serious invasive illness associated with consumption of contaminated food and places a significant burden on public health and the agricultural economy. We recently developed a multilocus genotyping (MLGT) assay for high-throughput subtype determination of L. monocytogenes lineage I isolates based on interrogation of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) via multiplexed primer extension reactions. Here we report the development and validation of two additional MLGT assays that address the need for comprehensive DNA sequence-based subtyping of L. monocytogenes. The first of these novel MLGT assays targeted variation segregating within lineage II, while the second assay combined probes for lineage III strains with probes for strains representing a recently characterized fourth evolutionary lineage (IV) of L. monocytogenes. These assays were based on nucleotide variation identified in >3.8 Mb of comparative DNA sequence and consisted of 115 total probes that differentiated 93% of the 100 haplotypes defined by the multilocus sequence data. MLGT reproducibly typed the 173 isolates used in SNP discovery, and the 10,448 genotypes derived from MLGT analysis of these isolates were consistent with DNA sequence data. Application of the MLGT assays to assess subtype prevalence among isolates from ready-to-eat foods and food-processing facilities indicated a low frequency (6.3%) of epidemic clone subtypes and a substantial population of isolates (>30%) harboring mutations in inlA associated with attenuated virulence in cell culture and animal models. These mutations were restricted to serogroup 1/2 isolates, which may explain the overrepresentation of serotype 4b isolates in human listeriosis cases.

Listeria monocytogenes is the causative agent of listeriosis, a food-borne disease with clinical presentations that include febrile gastroenteritis, encephalitis, meningitis, septicemia, and spontaneous abortion (7). Listeriosis infections are associated with high hospitalization (92%) and mortality (20 to 30%) rates and account for over one-quarter of all deaths attributable to known food-borne pathogens (12, 24). L. monocytogenes is widely distributed in the environment, forms biofilms, grows at refrigeration temperatures, and is relatively resistant to acid and high salt concentrations (23, 48). These characteristics enable L. monocytogenes to persist for extended periods in food-processing environments and make L. monocytogenes contamination of ready-to-eat (RTE) foods a significant concern. Accordingly, regulatory agencies have applied a zero tolerance policy for L. monocytogenes contamination in RTE foods, and L. monocytogenes has been a leading cause of food recalls due to microbial adulteration.

Molecular subtyping is a critical component of L. monocytogenes outbreak detection and epidemiological investigations, which are complicated by the long incubation time for invasive listeriosis and the difficulty in identifying appropriate controls for case-control studies (44). Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) is the current gold standard for subtyping most food-borne bacterial pathogens and has been used successfully to subtype L. monocytogenes isolates as part of the PulseNet system (11, 43). However, PFGE is labor-intensive, results in complex patterns which are not always easy to interpret, is unable to target specific polymorphisms, and does not always discriminate between related but distinct strains (4, 5, 11). In addition, PFGE patterns may be affected by unstable genetic elements that could interfere with outbreak detection and long-term epidemiological tracking. As a result, there has been significant interest in the development of DNA sequence-based subtyping assays for food-borne pathogens (5, 11, 16, 37, 42, 43, 50). Toward that end, we recently described a single-well DNA sequence-based subtyping method utilizing multilocus genotyping (MLGT) of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) segregating within L. monocytogenes lineage I that provides high discriminatory power and good epidemiological concordance (5).

While we previously focused on subtyping lineage I isolates because of their association with epidemic listeriosis, four major evolutionary lineages have been described for L. monocytogenes (22, 33, 36, 38, 46, 47). L. monocytogenes isolates from lineage II are common contaminants of RTE and other food products (13, 46), contribute significantly to sporadic listeriosis in humans (18), and include a previously described epidemic clonal lineage (epidemic clone III [ECIII]) responsible for a multistate outbreak in 2000 linked to turkey products (20, 31). Lineage III strains are primarily associated with animal listeriosis cases; however, approximately 1% of human sporadic listeriosis cases are attributable to lineage III (18). Several recent phylogenetic studies have demonstrated that isolates classified as subgroup IIIB represent a distinct fourth lineage of L. monocytogenes (22, 33, 38). In the present study, we refer to this group as lineage IV in order to make clear that this unique lineage is not part of, or even closely related to, a monophyletic lineage III. Fewer than a dozen isolates from lineage IV have been characterized to date, but these include human, animal, and food isolates (22, 33, 38). In order to address the need for comprehensive subtyping of all L. monocytogenes isolates, we describe the development and validation of a modular set of single-well assays for rapid SNP-based subtyping of lineage II, III, and IV isolates which complement our previously published lineage I assay (5).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and DNA sequence analysis.

A diverse panel of 173 L. monocytogenes isolates was used in the design and validation of the MLGT assays (Table 1). An additional 20 L. monocytogenes isolates from sporadic listeriosis cases were used in a comparative subtyping analysis (Table 2). Isolates were cultured in brain heart infusion broth or tryptic soy agar supplemented with 0.6% (wt/vol) yeast extract (Difco) at 37°C and can be acquired from the Agricultural Research Service Culture Collection (NCAUR, Peoria, IL). With the exception of lineage IV isolates, which were characterized by phylogenetic analyses of DNA sequence data, the lineage identity of individual isolates was determined using a multiplex PCR assay (46). PCR serogroups for lineage II isolates were determined following the method of Doumith et al. (2). This method does not permit discrimination of serotypes within lineages III or IV. Therefore, previously published serotype data are reported (1, 10, 46).

TABLE 1.

L. monocytogenes isolates used in development of multilocus genotyping assays

| NRRLa | Equivalent | Origin | Year | Lineage | Serotypeb | PCR serogroupc | STd | MLGTe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 33002 | RM2212 | Food | II | 1/2a | 1/2a complex | ST2-1 | Lm2.1 | |

| 33009 | RM2388 | Food | II | 1/2a | 1/2a complex | ST2-2 | Lm2.2 | |

| 33014 | 12443 | Animal | II | 1/2a | 1/2a complex | ST2-3 | Lm2.3 | |

| 33022 | DSM20600 | Animal | II | 1/2a | 1/2a complex | ST2-4 | Lm2.4 | |

| 33027 | Frankfurters | 2000 | II | 1/2a | 1/2a complex | ST2-5 | Lm2.5 (T700) | |

| 33029 | Hot dogs | 2000 | II | 1/2c | 1/2c complex | ST2-6 | Lm2.6 | |

| 33031 | Frankfurters | 1999 | II | 1/2a | 1/2a complex | ST2-7 | Lm2.7 | |

| 33034 | Corn beef | 2000 | II | 1/2a | 1/2a complex | ST2-8 | Lm2.8 (T189) | |

| 33035 | Sausage | 2000 | II | 1/2a | 1/2a complex | ST2-9 | Lm2.9 | |

| 33039 | Beef jerkey | 2000 | II | 1/2c | 1/2c complex | ST2-10 | Lm2.10 | |

| 33040 | Chicken salad | 2000 | II | 1/2a | 1/2a complex | ST2-9 | Lm2.9 | |

| 33041 | Red hots | 2000 | II | 1/2a | 1/2a complex | ST2-9 | Lm2.9 | |

| 33043 | Lunch meat | II | 1/2a | 1/2a complex | ST2-11 | Lm2.11 | ||

| 33044 | Hot dogs | II | 1/2a | 1/2a complex | ST2-11 | Lm2.11 | ||

| 33064 | 2064 | Animal | II | 1/2a | 1/2a complex | ST2-12 | Lm2.12 | |

| 33069 | 2070 | Milk | II | 1/2a | 1/2a complex | ST2-12 | Lm2.12 | |

| 33100 | 2612 | Animal | II | 1/2a | N/T | ST2-13 | Lm2.13 | |

| 33106 | 2420 | Milk | 1983 | II | 1/2a | 1/2a complex | ST2-14 | Lm2.14 |

| 33127 | 2063 | Animal | II | 1/2a | 1/2a complex | ST2-12 | Lm2.12 | |

| 33128 | 2153 | Potato | II | 1/2a | 1/2a complex | ST2-15 | Lm2.15 | |

| 33152 | 2072 | Milk | II | 1/2a | 1/2a complex | ST2-12 | Lm2.12 | |

| 33167 | 2362 | Environment | II | 1/2a | 1/2a complex | ST2-16 | Lm2.16 | |

| 33169 | SE106 | NAf | II | 1/2a | 1/2a complex | ST2-17 | Lm2.17 | |

| 33171 | H6900 | Human | II | 1/2a | 1/2a complex | ST2-53 | Lm2.12 | |

| 33180 | 41966-97 | Animal | II | 1/2a | 1/2a complex | ST2-53 | Lm2.12 | |

| 33189 | 32285-01 | Animal | II | 1/2a | 1/2a complex | ST2-18 | Lm2.18 | |

| 33215 | LMB0027 | Milk | II | 1/2a | 1/2a complex | ST2-12 | Lm2.12 | |

| 33216 | LMB0033 | Milk | II | 1/2a | 1/2a complex | ST2-54 | Lm2.12 | |

| 33219 | LMB0340 | Environment | II | 1/2a | 1/2a complex | ST2-19 | Lm2.19 (T700) | |

| 33223 | H9333 | Human | II | 1/2c | 1/2c complex | ST2-10 | Lm2.10 | |

| 33225 | J0095 | NA | II | 3a | 1/2a complex | ST2-20 | Lm2.20 (T492) | |

| 33226 | J0096 | NA | II | 3c | 1/2c complex | ST2-21 | Lm2.21 (T685) | |

| 33235 | Frankfurters | 2000 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-5 | Lm2.5 (T700) | ||

| 33236 | Frankfurters | 2000 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-22 | Lm2.22 | ||

| 33238 | Beef jerkey | 2000 | II | 1/2c complex | ST2-10 | Lm2.10 | ||

| 33241 | Sausage | 2000 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-5 | Lm2.5 (T700) | ||

| 33243 | Beef | 2000 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-11 | Lm2.11 | ||

| 33244 | NA | 2000 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-23 | Lm2.23 | ||

| 33246 | Chicken salad | 2000 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-9 | Lm2.9 | ||

| 33247 | Roast beef | 2000 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-9 | Lm2.9 | ||

| 33249 | NA | 2000 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-55 | Lm2.12 | ||

| 33253 | Ham | 2001 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-9 | Lm2.9 | ||

| 33255 | Sausage | 2001 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-7 | Lm2.7 | ||

| 33256 | Sausage | 2001 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-7 | Lm2.7 | ||

| 33257 | Roast beef | 2001 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-9 | Lm2.9 | ||

| 33259 | Chicken | 2001 | II | 1/2c complex | ST2-10 | Lm2.10 | ||

| 33260 | Sausage | 2001 | II | 1/2c complex | ST2-24 | Lm2.24 (T577) | ||

| 33264 | Beef | 2001 | II | 1/2c complex | ST2-10 | Lm2.10 | ||

| 33271 | NA | 2001 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-11 | Lm2.11 | ||

| 33274 | NA | 2001 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-11 | Lm2.11 | ||

| 33275 | NA | 2001 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-25 | Lm2.25 | ||

| 33276 | Chicken | 2001 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-56 | Lm2.12 | ||

| 33277 | NA | 2001 | II | 1/2c complex | ST2-10 | Lm2.10 | ||

| 33278 | NA | 2001 | II | 1/2c complex | ST2-10 | Lm2.10 | ||

| 33279 | NA | 2001 | II | 1/2c complex | ST2-10 | Lm2.10 | ||

| 33280 | NA | 2001 | II | 1/2c complex | ST2-10 | Lm2.10 | ||

| 33281 | Sausage | 2001 | II | 1/2c complex | ST2-26 | Lm2.26 | ||

| 33282 | Duck breast | 2001 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-5 | Lm2.5 (T700) | ||

| 33283 | Chicken base | 2001 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-5 | Lm2.5 (T700) | ||

| 33285 | Turkey breast | 2001 | II | 1/2c complex | ST2-10 | Lm2.10 | ||

| 33286 | Sausage | 2001 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-27 | Lm2.27 | ||

| 33288 | Beef | 2001 | II | 1/2c complex | ST2-10 | Lm2.10 | ||

| 33290 | Beef quesadilla | 2001 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-28 | Lm2.28 | ||

| 33292 | Turkey breast | 2001 | II | 1/2c complex | ST2-10 | Lm2.10 | ||

| 33295 | Chorizo | 2001 | II | 1/2c complex | ST2-10 | Lm2.10 | ||

| 33297 | Sausage | 2001 | II | 1/2c complex | ST2-26 | Lm2.26 | ||

| 33298 | Sausage | 2001 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-27 | Lm2.27 | ||

| 33299 | Sausage | 2001 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-27 | Lm2.27 | ||

| 33307 | Chicken breast | 2001 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-5 | Lm2.5 (T700) | ||

| 33310 | Ham | 2001 | II | 1/2c complex | ST2-29 | Lm2.29 | ||

| 33311 | Chicken quesadilla | 2001 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-30 | Lm2.30 (T189) | ||

| 33316 | Roast beef | 2001 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-31 | Lm2.31 | ||

| 33317 | Deli turkey | 2001 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-52 | Lm2.11 | ||

| 33318 | Turkey, cheese, deli | 2001 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-52 | Lm2.11 | ||

| 33319 | Frankfurters | 2001 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-11 | Lm2.11 | ||

| 33321 | Roast duckling | 2002 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-32 | Lm2.32 | ||

| 33324 | Pork spring rolls | 2002 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-33 | Lm2.33 (T700) | ||

| 33326 | Salami | 2002 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-34 | Lm2.34 (T492) | ||

| 33332 | Sausage | 2001 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-5 | Lm2.5 (T700) | ||

| 33335 | Pork chops | 2002 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-35 | Lm2.35 | ||

| 33336 | Pork chops | 2002 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-5 | Lm2.5 (T700) | ||

| 33338 | Pork | 2002 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-9 | Lm2.9 | ||

| 33339 | Chicken egg roll | 2002 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-33 | Lm2.33 (T700) | ||

| 33340 | Soujouk | 2002 | II | 1/2c complex | ST2-10 | Lm2.10 | ||

| 33342 | Turkey pastrami | 2002 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-11 | Lm2.11 | ||

| 33344 | Sausage | 2002 | II | 1/2c complex | ST2-26 | Lm2.26 | ||

| 33348 | Bologna | 2003 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-36 | Lm2.36 | ||

| 33349 | Pork chops | 2003 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-37 | Lm2.37 | ||

| 33350 | Sausage | 2003 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-51 | Lm2.9 | ||

| 33353 | Ham | 2003 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-38 | Lm2.38 (T492) | ||

| 33357 | Chicken salad | 2003 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-5 | Lm2.5 (T700) | ||

| 33380 | Animal | 2004 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-39 | Lm2.39 | ||

| 33387 | FSL J2-020 | Animal | 1986 | II | 1/2a | 1/2a complex | ST2-40 | Lm2.40 |

| 33395 | FSL C1-056 | Human | 1998 | II | 1/2a | 1/2a complex | ST2-53 | Lm2.12 |

| 33396 | FSL J2-054 | Animal | 1993 | II | 1/2a | 1/2a complex | ST2-41 | Lm2.41 |

| 33397 | FSL M1-004 | Human | 1997 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-11 | Lm2.11 | |

| 33398 | FSL J2-031 | Animal | 1996 | II | 1/2a | 1/2a complex | ST2-42 | Lm2.42 |

| 33399 | FSL J2-066 | Animal | 1994 | II | 1/2a | 1/2a complex | ST2-43 | Lm2.43 |

| 33402 | FSL C1-115 | Human | 1998 | II | 3a | 1/2a complex | ST2-44 | Lm2.44 |

| 33417 | F6854 | Hot dog | 2000 | II | 1/2a | 1/2a complex | ST2-1 | Lm2.1 |

| 33419 | J0161 | Human | 2000 | II | 1/2a | 1/2a complex | ST2-1 | Lm2.1 |

| 33427 | Environment | 2004 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-45 | Lm2.45 | ||

| 33428 | Turkey | 2003 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-46 | Lm2.46 | ||

| 33431 | Turkey | 2003 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-46 | Lm2.46 | ||

| 33433 | Salami | 2003 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-20 | Lm2.20 (T492) | ||

| 33435 | Environment | 2003 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-11 | Lm2.11 | ||

| 33436 | Environment | 2003 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-11 | Lm2.11 | ||

| 33437 | Environment | 2003 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-11 | Lm2.11 | ||

| 33438 | Pork | 2003 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-11 | Lm2.11 | ||

| 33439 | Pork | 2003 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-11 | Lm2.11 | ||

| 33440 | Pork | 2003 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-11 | Lm2.11 | ||

| 33441 | Pork | 2003 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-11 | Lm2.11 | ||

| 33443 | Roast beef | 2003 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-30 | Lm2.30 (T189) | ||

| 33446 | Chicken breast | 2003 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-9 | Lm2.9 | ||

| 33447 | Food | 2003 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-47 | Lm2.47 | ||

| 33448 | Ham | 2003 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-7 | Lm2.7 | ||

| 33449 | Prosciutto | 2003 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-5 | Lm2.5 (T700) | ||

| 33450 | Prosciutto | 2003 | II | 1/2c complex | ST2-24 | Lm2.24 (T577) | ||

| 33452 | Chicken burrito | 2004 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-1 | Lm2.1 | ||

| 33454 | Environment | 2004 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-50 | Lm2.5 (T700) | ||

| 33455 | Beef | 2004 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-5 | Lm2.5 (T700) | ||

| 33456 | Ham | 2004 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-5 | Lm2.5 (T700) | ||

| 33460 | Environment | 2004 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-48 | Lm2.48 | ||

| 33467 | Environment | 2004 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-49 | Lm2.49 | ||

| 33468 | Pork | 2004 | II | 1/2a complex | ST2-5 | Lm2.5 (T700) | ||

| 33077 | 7035 | Animal | III | 4b | ST3-1 | Lm3.1 | ||

| 33092 | 7678 | Animal | III | 4b | ST3-2 | Lm3.2 | ||

| 33105 | 7676 | Animal | III | 4b | ST3-3 | Lm3.3 | ||

| 33115 | 3890 | Animal | III | 4c | ST3-16 | Lm3.16 | ||

| 33177 | 28838-95 | Animal | III | 4c | ST3-4 | Lm3.4 | ||

| 33181 | 1709-98 | Animal | III | 4b | ST3-5 | Lm3.5 | ||

| 33182 | 7259-98 | Animal | III | 4c | ST3-6 | Lm3.6 | ||

| 33183 | 20842-98 | Animal | III | 4b | ST3-7 | Lm3.7 | ||

| 33184 | 11466-01 | Animal | III | 4c | ST3-8 | Lm3.8 | ||

| 33185 | 12459-01 | Animal | III | 4b | ST3-9 | Lm3.9 | ||

| 33187 | 22409-01 | Animal | III | 4b | ST3-10 | Lm3.10 | ||

| 33188 | 23594-01 | Animal | III | 4c | ST3-11 | Lm3.11 | ||

| 33190 | 36087-01 | Animal | III | 4b | ST3-12 | Lm3.12 | ||

| 33191 | 50301-01 | Animal | III | 4b | ST3-13 | Lm3.13 | ||

| 33227 | J0099 | NA | III | 4c | ST3-14 | Lm3.14 | ||

| 33229 | ILSI19 | Human | III | 4c | ST3-38 | Lm3.38 | ||

| 33230 | LMB0291 | Food | III | 4b | ST3-15 | Lm3.15 | ||

| 33231 | ATCC19116 | Food | III | 4c | ST3-16 | Lm3.16 | ||

| 33330 | Liquid whole egg | 2002 | III | ST3-17 | Lm3.17 | |||

| 33360 | Human | III | ST3-18 | Lm3.18 | ||||

| 33362 | Animal | 2002 | III | ST3-27 | Lm3.27 | |||

| 33363 | Animal | 2002 | III | ST3-19 | Lm3.19 | |||

| 33364 | Animal | 2002 | III | ST3-21 | Lm3.21 | |||

| 33365 | Animal | 2002 | III | ST3-20 | Lm3.20 | |||

| 33366 | Animal | 2002 | III | ST3-21 | Lm3.21 | |||

| 33367 | Animal | 2002 | III | ST3-22 | Lm3.22 | |||

| 33368 | Animal | 2003 | III | ST3-23 | Lm3.23 | |||

| 33370 | Animal | 2003 | III | ST3-24 | Lm3.24 | |||

| 33371 | Animal | 2003 | III | ST3-25 | Lm3.25 | |||

| 33372 | Animal | 2004 | III | ST3-26 | Lm3.26 | |||

| 33373 | Animal | 2004 | III | ST3-27 | Lm3.27 | |||

| 33374 | Animal | 2004 | III | ST3-28 | Lm3.28 | |||

| 33375 | Animal | 2004 | III | ST3-29 | Lm3.29 | |||

| 33376 | Animal | 2004 | III | ST3-30 | Lm3.30 | |||

| 33377 | Animal | 2004 | III | ST3-31 | Lm3.31 | |||

| 33378 | Animal | 2004 | III | ST3-32 | Lm3.32 | |||

| 33379 | Animal | 2004 | III | ST3-33 | Lm3.33 | |||

| 33381 | Animal | 2004 | III | ST3-34 | Lm3.34 | |||

| 33382 | Animal | 2004 | III | ST3-35 | Lm3.35 | |||

| 33383 | Animal | 2004 | III | ST3-36 | Lm3.36 | |||

| 33384 | Animal | 2004 | III | ST3-37 | Lm3.37 | |||

| 33403 | FSL J1-031 | Human | III | 4a | ST3-38 | Lm3.38 | ||

| 33407 | FSL W1-110 | NA | III | 4c | ST3-39 | Lm3.39 | ||

| 33425 | Animal | III | ST3-40 | Lm3.40 | ||||

| 33426 | FDA 3365 | Food | III | 4b | ST3-41 | Lm3.41 | ||

| 33405 | FSL W1-111 | NA | IV | 4c | ST4-1 | Lm4.1 | ||

| 33406 | FSL W1-112 | NA | IV | 4a | ST4-2 | Lm4.2 | ||

| 33408 | FSL J1-158 | Animal | 1997 | IV | 4b | ST4-3 | Lm4.3 |

Isolates are identified with NRRL-B numbers from the U.S. Department of Agriculture ARS Culture Collection, Peoria, IL. Additional strain history information is available from the ARS Culture Collection website (http://nrrl.ncaur.usda.gov/cgi-bin/usda).

Serotypes were previously reported (1, 10, 46) or were previously determined by a reference laboratory.

Determined using the method of Doumith et al., which was not designed to discriminate serotypes within lineages III or IV (2).

ST, sequence type.

The amino acid positions of premature stop codons in inlA relative to the 800-amino-acid protein predicted for strain EGD-e (NC_003210) are indicated parenthetically following the MLGT designation.

NA, not available.

TABLE 2.

Comparative subtype data for sporadic human listeriosis isolates

| NRRLa | Equivalent | Serotypeb | MLGTc | AscI pattern | ApaI pattern | MVLSTd | MLSTe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 33555 | J0221 | 1/2a | Lm2.46 | GX6A16.0170 | GX6A12.0316 | 2 | 2 |

| 33556 | J0809 | 1/2a | Lm2.50 | GX6A16.0401 | GX6A12.0519 | 1 | 1 |

| 33557 | J0834 | 1/2a | Lm2.11 | GX6A16.0018 | GX6A12.0022 | 5 | 5 |

| 33558 | J0846 | 1/2a | Lm2.11 | GX6A16.0034 | GX6A12.0022 | 5 | 5 |

| 33559 | J0847 | 1/2a | Lm2.46 | GX6A16.0233 | GX6A12.0467 | 2 | 2 |

| 33560 | J1038 | 1/2a | Lm2.9 | GX6A16.0010 | GX6A12.0005 | 3 | 3 |

| 33561 | J1108 | 1/2a | Lm2.28 | GX6A16.0458 | GX6A12.0559 | 5 | 5 |

| 33562 | J1219 | 1/2a | Lm2.11 | GX6A16.0018 | GX6A12.0022 | 5 | 5 |

| 33563 | J1769 | 1/2a | Lm2.44 | GX6A16.0055 | GX6A12.0708 | 4 | 4 |

| 33564 | J2061 | 1/2a | Lm2.11 | GX6A16.0018 | GX6A12.0022 | 5 | 5 |

| 33565 | J2342 | 1/2a | Lm2.51 | GX6A16.0675 | GX6A12.0716 | 6 | 6 |

| 33566 | J2692 | 1/2a | Lm2.12 | GX6A16.0083 | GX6A26.0598 | 10 | 11 |

| 33567 | J2980 | 1/2a | Lm2.52 | GX6A16.0347 | GX6A12.0031 | 7 | 7 |

| 33568 | J3560 | 1/2a | Lm2.15 | GX6A16.0849 | GX6A12.0451 | 8 | 8 |

| 33575 | J1109 | 1/2c | Lm2.10 | GX6A16.0057 | GX6A12.0085 | 9 | 10 |

| 33576 | J1131 | 1/2c | Lm2.10 | GX6A16.0279 | GX6A12.0356 | 9 | 9 |

| 33577 | J2252 | 1/2c | Lm2.10 | GX6A16.0082 | GX6A12.0705 | 9 | 10 |

| 33578 | J2283 | 1/2c | Lm2.24 | GX6A16.0057 | GX6A12.0085 | 9 | 10 |

| 33579 | J2315 | 1/2c | Lm2.10 | GX6A16.0082 | GX6A12.0679 | 9 | 10 |

| 33580 | J0845 | 3a | Lm2.12 | GX6A16.0609 | GX6A12.0797 | 10 | 11 |

Isolates are identified with NRRL-B numbers from the U.S. Department of AgricultureARS Culture Collection, Peoria, IL. Additional strain history information is available from the ARS Culture Collection website (http://nrrl.ncaur.usda.gov/cgi-bin/usda).

Serotype data were provided by Lewis Graves (CDC).

Lm2.50 to 2.52 were not observed in the original set of sequenced isolates (Table 1).

Multi-virulence locus sequence typing was performed as described by Zhang et al. (50).

Multilocus sequence typing was performed as described by Revazishvili et al. (37).

In order to identify SNPs and other genetic polymorphisms segregating within lineage II, we sequenced 24,852 bp of DNA from each of 125 isolates (Table 1). This comparative DNA sequence database encompassed 12 regions of the L. monocytogenes genome and included genes responsible for virulence, stress response, and housekeeping functions (Table 3). Eight of these regions corresponded to those used in the lineage I MLGT assay (5), although VGC sequences for lineage II isolates were collected in two nonoverlapping segments (VGCa and VGCb). Three additional regions (ARO, PUR, and TRU) were included in the SNP discovery based on their high levels of sequence divergence in comparisons of EGD-e (GenBank accession number NC_003210) and F6854 (GenBank accession number AADQ00000000) genome sequences. The TRP region was included in the SNP discovery due to variation identified while characterizing a putative small noncoding RNA (sRNA) in the intergenic region between trpE and lmo1634. Due to high levels of sequence divergence observed for lineage III and IV isolates, SNP discovery for these lineages focused on the three most informative regions from the lineage I assay (5) and included 14,881 bp of DNA sequence (Table 3) from each of 48 isolates (Table 1). DNA isolation and sequencing were performed as previously described (46). PCR amplification protocols were previously described (5, 46) or are provided in the supplemental material.

TABLE 3.

Single nucleotide polymorphism and haplotype variations among 173 L. monocytogenes isolates

| Lineage(s) | Region | Positiona | Genes or locib | No. of SNPs | No. of haplotypes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| II | VGCa | 205,814-208,259 | hly, mpl | 43 | 28 |

| II | VGCb | 209,573-211,447 | actA, plcB | 92 | 25 |

| II | LMO | 325,093-327,031 | lmo0298, lmo0299, lmo0300 | 160 | 26 |

| II | INL | 454,789-458,788 | inlA, inlB | 139 | 31 |

| II | SIG | 930,314-931,861 | rsbV, rsbW, sigB, | 16 | 14 |

| II | PDH | 1,079,263-1,081,952 | pdhA, pdhB, pdhC | 106 | 22 |

| II | TRU | 1,356,824-1,357,931 | truB, ribC | 202 | 18 |

| II | AMI | 1,553,548-1,555,355 | ami, hisS | 27 | 16 |

| II | ACC | 1,612,612-1,614,874 | accD, dnaE | 143 | 25 |

| II | TRP | 1,676,679-1,678,787 | lmo1634 | 69 | 23 |

| II | PUR | 1,838,571-1,840,142 | purN, purM, purF | 237 | 24 |

| II | ARO | 1,998,007-1,999,495 | tyrA, aroE, lmo1922 | 185 | 25 |

| III & IV | VGC | 203,659-212,465 | prfA, plcA, hly, mpl, actA, plcB, lmo0206 | 876 | 42 |

| III & IV | LMO | 325,093-327,032 | lmo0298, lmo0299, lmo0300 | 228 | 39 |

| III & IV | INL | 454,708-458,828 | inlA, inlB | 510 | 40 |

Corresponding nucleotide positions in the complete genome sequence of L. monocytogenes strain EGD-e (NC_003210).

Gene designations follow the annotated EGD-e genome (NC_003210).

DNA sequences were edited and aligned with Sequencher (version 4.1.2; Gene Codes), variable sites were identified with MEGA (version 4.0), and unique multilocus haplotypes were identified with DAMBE (49). Uncorrected genetic distance values (p-distances) were estimated in MEGA. Prior to phylogenetic or haplotype analyses, ambiguously aligned characters were removed from the data set and insertion or deletion (indel) polymorphisms that defined unique haplotypes were coded as single events. Distance analyses were performed using the neighbor-joining algorithm and the Kimura two-parameter model as implemented in MEGA. Maximum parsimony analyses were conducted using the tree bisection and reconnection method of branch swapping and the heuristic search algorithm of PAUP* (version 4.0B; Sinauer Associates). Relative support for individual nodes was assessed by bootstrap analysis with 2,000 replications (8, 35).

Multilocus genotyping assays.

In the present study, we developed and validated two MLGT assays using the approach and platform previously described for the lineage I assay (5). The first of these novel MLGT assays specifically targeted SNP variation segregating within lineage II, while we combined probes for lineages III and IV in a single MLGT assay. In order to provide for simultaneous interrogation of strain-discriminating polymorphisms identified in the comparative sequence analysis, multiple genomic regions were coamplified via an assay-specific multiplex PCR, which utilized seven sets of amplification primers for the lineage II assay and five sets of amplification primers for the lineage III and IV assay (Table 4). Multiplex amplifications were performed in 50-μl reaction mixtures and included 2 mM MgSO4, 100 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 300 nM primer, 1.5 U Platinum Taq DNA polymerase High Fidelity (Invitrogen Life Technologies), and 100 ng of genomic DNA. PCR consisted of an initial denaturation of 90 s at 96°C, followed by 40 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 45 s at 50°C, and 150 s at 68°C. Amplification products were purified using Montage PCR cleanup filter plates (Millipore) and served as templates for allele-specific primer extension (ASPE) reactions.

TABLE 4.

Primers used in multiplex amplifications for the MLGT assays

| Lineage(s) | Region | Primer | Sequence (5′-3′)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| II-III-IV | VGCa | hly-F2 | GAAGGAGAGTGAAACCCATG |

| II-III-IV | VGCa | mpl-R | CTCGCAACTTCYGGCTCAGC |

| II-III-IV | VGCb | actA-F | CCAAYTGCATTACGATTAACC |

| II-III-IV | VGCb | plcB-R | CAAGCACATACCTAGAACCAC |

| II-III-IV | INLa | inlA-F2 | ACGAAYGTAACAGACACGGTC |

| II | INLa | inlA-R2 | CTACTTCTATTTACTAGCACG |

| III-IV | INLa | inlA-R3 | TCTAGCTCTTYACACTACTTC |

| II-III-IV | INLb | inlB-F2 | AATCAAGGAGAGGATAGTGTG |

| II-III-IV | INLb | inlB-R | CTACCGGRACTTTATAGTAYG |

| II | LMO | lmo0300-F | GATTGGATTAAGTACGAGC |

| II | LMO | lmo0298-R | CTCTTATCAATGTGAAGGTGC |

| III-IV | LMO | lmo0300-F2 | ATGTRGCGAGCGATCACTACC |

| III-IV | LMO | lmo0300-R2 | AATCTTCGTGRTAGTGTTTGC |

| II | TRP | adhE-F | TGGAAGTTTGAACCATTGCAT |

| II | TRP | adhE-R | AGGACGAGAGACCCGTGGTA |

| II | ACC | dnaE-F | GGATTTTCDCTTGGAGAAGCAG |

| II | ACC | dnaE-R | CRCCGACAACAGARCCCATAC |

See IUPAC codes for definitions of degenerate bases.

We performed ASPE in multiplex reactions containing 64 (lineage II assay) or 51 (lineage III and IV assay) probes (Table 5). ASPE probes were designed with unique 5′ sequence tags corresponding to individual sets of Luminex xMAP fluorescent polystyrene microspheres (Luminex Corporation). These probes served as allele-specific primers in extension reactions producing single-stranded DNA extension products from template DNA containing the probe sequence. Extensions were performed in 20-μl reaction mixtures and included 2 mM MgCl2, 5 μM biotin-dCTP, 5 μM dATP/dGTP/dTTP, 25 nM primer, 0.75 U Platinum GenoTYPE Tsp DNA polymerase (Invitrogen Life Technologies). Five μl of purified multiplex PCR amplicon was added as template for extension reactions performed with an initial denaturation of 120 s at 96°C, followed by 40 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 60 s at 52°C, and 120 s at 74°C.

TABLE 5.

ASPE probes and probe performance data

| Probeb | Probe sequencec | Adjusted MFI (range)

|

Target Nd | IDe | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nontarget | Target | ||||

| Lm2.ACC1 (94) | CTTTCTATCTTTCTACTCAATAATccgttatgtttccggaatgtc | 7-183 | 1,943-2,340 | 1 | 10.6 |

| Lm2.ACC2 (11) | TACAAATCATCAATCACTTTAATCggtattatgacaaaatgtccg | 44-158 | 2,379-3,043 | 14 | 15.1 |

| Lm2.ACC3 (67) | TCATTTACTCAACAATTACAAATCaagaagaaagcggatgtcctg | 104-231 | 2,916-2,935 | 1 | 12.6 |

| Lm2.ACC4 (63) | CTACTTCATATACTTTATACTACAggggatagtaaggttatcgtt | −3 to 193 | 3,424-4,285 | 4 | 17.8 |

| Lm2.ACC5 (55) | TATATACACTTCTCAATAACTAACgacgattttggcaactattgatgt | 48-208 | 3,949-3,974 | 1 | 19.0 |

| Lm2.ACCx (69) | CTATAAACATATTACATTCACATCgtttcagcgcayccagtatcg | N/Aa | 3,118-4,842 | 125 | N/A |

| Lm2.INLa1 (5) | CAATTCAAATCACAATAATCAATCcaccaccttccgcaaatatag | 266-545 | 5,880-6,371 | 1 | 10.8 |

| Lm2.INLa10 (13) | CAATAAACTATACTTCTTCACTAAaacagatggkaaaaaatg | 60-63 | 1,399-3,002 | 124 | 22.3 |

| Lm2.INLa11 (98) | AATCATACTCAACTAATCATTCAAaaacaggyggaactaaatggrat | 56-73 | 320-1,569 | 123 | 4.4 |

| Lm2.INLa12 (8) | AATCCTTTTACATTCATTACTTACgcaaatgacattacgctgtag | 16-165 | 2,063-2,806 | 17 | 12.5 |

| Lm2.INLa13 (59) | TCATCAATCAATCTTTTTCACTTTgtgcgctttcaggtttaactagtctat | 95-254 | 2,390-2,882 | 3 | 9.4 |

| Lm2.INLa14 (65) | CTTTTCATCAATAATCTTACCTTTcatttagtggaactgtgacgt | 22-127 | 2,172-2,508 | 4 | 17.2 |

| Lm2.INLa15 (97) | AATCTCATAATCTACATACACTATaaacaggyggaactaaatggat | 27-97 | 1,981-2,380 | 2 | 20.5 |

| Lm2.INLa2(54) | CTTTTTCAATCACTTTCAATTCATgcaccactgtcgggtctaacg | 143-307 | 2,436-2,645 | 1 | 7.9 |

| Lm2.INLa3 (28) | CTACAAACAAACAAACATTATCAAcgaaaaaacagatgggaaaaaata | 17-133 | 981-1,048 | 1 | 7.4 |

| Lm2.INLa4 (23) | TTCAATCATTCAAATCTCAACTTTccttatatgcccaatatagcgct | 41-246 | 4,533-4,839 | 1 | 18.4 |

| Lm2.INLa5 (74) | TACACATCTTACAAACTAATTTCAcggatataacgccacttaaag | 20-108 | 852-1,417 | 39 | 7.9 |

| Lm2.INLa6 (12) | TACACTTTCTTTCTTTCTTTCTTTaactaatctacagcaattatt | −13 to 72 | 487-582 | 1 | 6.7 |

| Lm2.INLa7 (100) | CTATCTTTAAACTACAAATCTAACgcaaatgayattacgctgtac | 54-100 | 1,194-2,157 | 108 | 12.0 |

| Lm2.INLa8 (70) | ATACCAATAATCCAATTCATATCAgtgcgctttcaggtttaaytartctac | 52-82 | 753-1,542 | 122 | 9.2 |

| Lm2.INLa9 (43) | CTTTCAATTACAATACTCATTACAcatttagtggaacygtgacgc | 39-59 | 1,103-2,309 | 121 | 18.6 |

| Lm2.INLax (62) | TCAATCATAATCTCATAATCCAATccaaataagtaacatcagtc | N/A | 906-1,751 | 125 | N/A |

| Lm2.INLb1 (29) | AATCTTACTACAAATCCTTTCTTTgatgttgatggaacggtaatt | 47-202 | 2,129-2,331 | 1 | 10.5 |

| Lm2.INLb2 (60) | AATCTACAAATCCAATAATCTCATggatagtgtgaaagaaaagcacg | 18-125 | 678-838 | 1 | 5.4 |

| Lm2.INLb3 (20) | CTTTTACAATACTTCAATACAATCcttccacgagaagataactca | 72-197 | 4,568-4,847 | 1 | 23.1 |

| Lm2.INLb4 (73) | ATCAAATCTCATCAATTCAACAATccgaaaaagcagtcaacttaact | 66-185 | 4,930-5,110 | 1 | 26.6 |

| Lm2.INLb5 (72) | TCATTTACCTTTAATCCAATAATCcaagcggagactatcaccgtgt | 45-115 | 2,249-2,804 | 22 | 19.5 |

| Lm2.INLb6 (18) | TCAAAATCTCAAATACTCAAATCAcgtatcttgcgcgaagccaaaacg | 128-242 | 2,391-3,030 | 14 | 9.9 |

| Lm2.INLbx (24) | TCAATTACCTTTTCAATACAATACgtacaagcggagactatcacc | N/A | 1,315-2,072 | 125 | N/A |

| Lm2.LMO1 (26) | TTACTCAAAATCTACACTTTTTCAactcggattcgctataagcat | 68-269 | 5,230-5,319 | 1 | 19.5 |

| Lm2.LMO10 (86) | CTAATTACTAACATCACTAACAATcgaatgcagcacaaacgtcgg | 1-314 | 6,231-7,806 | 20 | 19.8 |

| Lm2.LMO11 (22) | AATCCTTTTTACTCAATTCAATCAcgtatctagcaagttttgatag | −28 to 826 | 8,534-10,203 | 8 | 10.3 |

| Lm2.LMO12 (14) | CTACTATACATCTTACTATACTTTtggcgttgctggctaagttta | 32-106 | 1,458-2,039 | 23 | 13.8 |

| Lm2.LMO2 (3) | TACACTTTATCAAATCTTACAATCgtgttgccagaagcggcttca | 44-179 | 1,945-2,045 | 1 | 10.9 |

| Lm2.LMO3 (30) | TTACCTTTATACCTTTCTTTTTACtcgtgcgattttgctagttct | 61-401 | 8,661-9,449 | 1 | 21.6 |

| Lm2.LMO4 (76) | AATCTAACAAACTCATCTAAATACcacaaacggctcaatatcaaa | 30-126 | 2,612-2,864 | 1 | 20.8 |

| Lm2.LMO5 (6) | TCAACAATCTTTTACAATCAAATCcaggcaagcaggaagccatta | 46-217 | 4,267-4,554 | 1 | 19.6 |

| Lm2.LMO6 (16) | AATCAATCTTCATTCAAATCATCAggagaccaagcgtagtagccg | 153-311 | 5,100-7,093 | 39 | 16.4 |

| Lm2.LMO7 (19) | TCAATCAATTACTTACTCAAATACggcagcatggacataaaggcg | 113-242 | 1,417-1,572 | 1 | 5.9 |

| Lm2.LMO8 (9) | TAATCTTCTATATCAACATCTTACttcgccagttcggcaaygaggtca | 27-388 | 2,770-7,807 | 12 | 7.1 |

| Lm2.LMO9 (37) | CTTTTCATCTTTTCATCTTTCAATcacaaccagcatcgattgcgtta | 46-168 | 2,866-3,809 | 9 | 17.1 |

| Lm2.LMOx (56) | CAATTTACTCATATACATCACTTTcgattaagccatcttgtaagcc | N/A | 2,368-4,315 | 125 | N/A |

| Lm2.TRP1 (77) | CAATTAACTACATACAATACATACgacaaatacccactatctcat | 219-781 | 3,431-5,879 | 3 | 4.4 |

| Lm2.TRP2 (88) | TTACTTCACTTTCTATTTACAATCgtgacatttataacggcttcatca | 524-930 | 10,830-11,262 | 1 | 11.6 |

| Lm2.TRP3 (93) | CTTTCTATTCATCTAAATACAAACcaagtaagaaaaaagaactacccg | 26-122 | 3,373-4,622 | 17 | 27.7 |

| Lm2.TRP4 (89) | TATACTATCAACTCAACAACATATcaaatgataattcgcttaaatct | 28-141 | 3,133-3,359 | 1 | 22.3 |

| Lm2.TRP5 (91) | TTCATAACATCAATCATAACTTACgcaacaagctaaatttttttggg | 100-234 | 2,937-3,000 | 1 | 12.6 |

| Lm2.TRPx (78) | CTATCTATCTAACTATCTATATCAcacatcatgtccgctactgac | N/A | 742-1,506 | 125 | N/A |

| Lm2.VGCa1 (80) | CTAACTAACAATAATCTAACTAACggagagtgaaaacccatgaaaaaat | 24-101 | 528-544 | 1 | 5.2 |

| Lm2.VGCa2 (96) | ATACTAACTCAACTAACTTTAAACctgaagcaaaggatgcatctgt | 14-118 | 770-931 | 1 | 6.5 |

| Lm2.VGCa3 (44) | TCATTTACCAATCTTTCTTTATACgcttttgatgctgccgtaagt | 60-134 | 1,935-2,033 | 1 | 14.4 |

| Lm2.VGCa4 (2) | CTTTATCAATACATACTACAATCAgagaaacaccaggagttcccg | 166-322 | 3,646-3,873 | 1 | 11.3 |

| Lm2.VGCa5 (21) | AATCCTTTCTTTAATCTCAAATCAggagatgcagtgacaaatgtgcca | 39-140 | 1,322-1,420 | 1 | 9.4 |

| Lm2.VGCa6 (51) | TCATTTCAATCAATCATCAACAATgcaaaacgtataatttagttct | 25-105 | 1,870-2,066 | 2 | 17.8 |

| Lm2.VGCa7 (66) | TAACATTACAACTATACTATCTACagcttgggaatggtggagaaa | 152-271 | 998-1,185 | 3 | 3.7 |

| Lm2.VGCa8 (57) | CAATATCATCATCTTTATCATTACagttgtaggtggcttaaactc | 15-82 | 365-587 | 18 | 4.4 |

| Lm2.VGCa9 (17) | CTTTAATCCTTTATCACTTTATCAgaccggaacctaccacttgta | 53-171 | 2,816-2,952 | 1 | 16.5 |

| Lm2.VGCax (40) | CTTTCTACATTATTCACAACATTAcactcagcattgatttgccagg | N/A | 721-2,016 | 125 | N/A |

| Lm2.VGCb1 (41) | TTACTACACAATATACTCATCAATtttgccagagacaccgatgca | 17-199 | 4,435-4,499 | 1 | 22.3 |

| Lm2.VGCb2 (10) | ATCATACATACATACAAATCTACAgacataactaaaaaagcgccattc | 24-129 | 3,518-4,056 | 1 | 27.3 |

| Lm2.VGCb3 (35) | CAATTTCATCATTCATTCATTTCAccgaccgaccagctatacaagta | 15-362 | 2,783-3,117 | 1 | 7.7 |

| Lm2.VGCb4 (1) | CTTTAATCTCAATCAATACAAATCgcaaacaggaaatgtggctac | 6-180 | 1,549-2,654 | 15 | 8.6 |

| Lm2.VGCb5 (85) | ATACTACATCATAATCAAACATCAcaccaaagctagcagaacttccta | 84-450 | 4,210-5,031 | 4 | 9.4 |

| Lm2.VGCbx (7) | CAATTCATTTACCAATTTACCAATgcagcgacagatagcgaaga | N/A | 1,241-3,935 | 125 | N/A |

| Lm3-4.INLa1 (76) | AATCTAACAAACTCATCTAAATACgcaccaccaacaactggagga | 74-477 | 3,026-3,861 | 2 | 6.3 |

| Lm3-4.INLa2 (19) | TCAATCAATTACTTACTCAAATACgctcaatatagcgccaatagctt | 33-199 | 2,294-2,484 | 1 | 11.5 |

| Lm3-4.INLa3 (74) | TACACATCTTACAAACTAATTTCAgcaacgtttgataatgacggtt | 55-252 | 2,932-3,403 | 1 | 11.6 |

| Lm3-4.INLa4 (88) | TTACTTCACTTTCTATTTACAATCgcaacctttgatgttgatggg | 357-683 | 5,316-8,397 | 15 | 7.8 |

| Lm3-4.INLa5 (95) | TACACTTTAAACTTACTACACTAAgcaacctttgatgttgatgga | 458-1,026 | 2,506-4,353 | 33 | 2.4 |

| Lm3-4.INLa6 (94) | CTTTCTATCTTTCTACTCAATAATgacatcgatttatatgcgct | 6-122 | 3,325-3,468 | 1 | 27.4 |

| Lm3-4.INLa7 (43) | CTTTCAATTACAATACTCATTACAtaaatcggctagaactatcc | 1-108 | 1,802-1,865 | 1 | 16.8 |

| Lm3-4.INLa8 (68) | TCATAATCTCAACAATCTTTCTTTgtcccctaacaggtctaact | 45-217 | 2,217-2,333 | 1 | 10.2 |

| Lm3-4.INLa9 (51) | TCATTTCAATCAATCATCAACAATcagctacacagcaacgttta | 18-150 | 1,402-1,521 | 1 | 9.4 |

| Lm3-4.INLax (12) | TACACTTTCTTTCTTTCTTTCTTTgtgatattagtgcgctttcagg | N/Aa | 2,634-5,197 | 48 | N/A |

| Lm3-4.INLb1 (17) | CTTTAATCCTTTATCACTTTATCAgcacgatttcatgggagagtaat | 153-481 | 3,418-4,144 | 1 | 7.1 |

| Lm3-4.INLb2 (29) | AATCTTACTACAAATCCTTTCTTTccttacaatacagccggct | −37 to 129 | 9,517-10,444 | 1 | 73.7 |

| Lm3-4.INLb3 (32) | ATTATTCACTTCAAACTAATCTACgaatatgacaaaggtgttactt | 42-211 | 2,417-2,589 | 1 | 11.5 |

| Lm3-4.INLb4 (72) | TCATTTACCTTTAATCCAATAATCcacttgtgaacaagctttct | 27-144 | 3,308-3,515 | 1 | 23.1 |

| Lm3-4.INLb5 (6) | TCAACAATCTTTTACAATCAAATCgaggcagggacgcgaataat | 179-445 | 2,074-2,270 | 1 | 4.7 |

| Lm3-4.INLb6 (37) | CTTTTCATCTTTTCATCTTTCAATggaatccagtatttacccc | −5 to 97 | 3,654-3,740 | 1 | 37.7 |

| Lm3-4.INLb7 (62) | TCAATCATAATCTCATAATCCAATctcgcaccgctgtaaagctc | 24-163 | 2,506-2,515 | 1 | 15.3 |

| Lm3-4.INLb8 (73) | ATCAAATCTCATCAATTCAACAATaacggggcgaaagtacaagcc | 49-177 | 3,231-3,515 | 1 | 18.2 |

| Lm3-4.INLbx (100) | CTATCTTTAAACTACAAATCTAACtatgcgaatattgcgcgaagcc | N/A | 2,051-3,476 | 48 | N/A |

| Lm3-4.LMO1 (20) | CTTTTACAATACTTCAATACAATCtttgcccaggatagccaccc | 28-540 | 4,538-6,339 | 5 | 8.4 |

| Lm3-4.LMO2 (2) | CTTTATCAATACATACTACAATCAgccgcgaacatcacaaccagt | 56-989 | 4,372-9,565 | 9 | 4.4 |

| Lm3-4.LMOx (59) | TCATCAATCAATCTTTTTCACTTTcgattaagccatcttgtaagcc | N/A | 2,238-6,590 | 48 | N/A |

| Lm3-4.VGCa1 (3) | TACACTTTATCAAATCTTACAATCcaggtgatgtagaattaacg | 62-277 | 3,464-3,693 | 1 | 12.5 |

| Lm3-4.VGCa2 (99) | AATCTACACTAACAATTTCATAACgcctaacatatccaggtgca | 33-178 | 2,823-3,013 | 1 | 15.9 |

| Lm3-4.VGCa3 (91) | TTCATAACATCAATCATAACTTACctttatccgaaatatagtaatagc | 17-331 | 2,417-2,718 | 1 | 7.3 |

| Lm3-4.VGCa4 (70) | ATACCAATAATCCAATTCATATCAgcatatcccaaagtttaagt | 83-227 | 4,419-5,184 | 1 | 19.4 |

| Lm3-4.VGCa5 (48) | AAACAAACTTCACATCTCAATAATgtaaaagaatgtctggcttta | 32-414 | 4,849-5,369 | 2 | 11.7 |

| Lm3-4.VGCa6 (64) | CTACATATTCAAATTACTACTTACattgatgaccggaacttaccg | 42-554 | 4,879-6,285 | 3 | 8.8 |

| Lm3-4.VGCa7 (42) | CTATCTTCATATTTCACTATAAACgaccggaacttaccacttgta | 52-309 | 3,452-3,651 | 1 | 11.2 |

| Lm3-4.VGCa8 (49) | TCATCAATCTTTCAATTTACTTACggagttcccattgcttatacaacc | 98-262 | 5,326-5,495 | 1 | 20.4 |

| Lm3-4.VGCa9 (26) | TTACTCAAAATCTACACTTTTTCAggaggctacgttgctcaattcaat | 620-1,652 | 9,110-9,702 | 1 | 5.5 |

| Lm3-4.VGCax (28) | CTACAAACAAACAAACATTATCAAgtataccacggagatgcagtgac | N/A | 498-1,304 | 48 | N/A |

| Lm3-4.VGCb1 (77) | CAATTAACTACATACAATACATACcaatcccaacagaagaagagg | 54-912 | 8,267-9,471 | 1 | 9.1 |

| Lm3-4.VGCb2 (14) | CTACTATACATCTTACTATACTTTcgtcatccaggattgccatca | 30-968 | 7,661-8,679 | 1 | 7.9 |

| Lm3-4.VGCb3 (57) | CAATATCATCATCTTTATCATTACgcttgaaagccttacttatctgt | 16-383 | 2,970-3,421 | 1 | 7.8 |

| Lm3-4.VGCb4 (35) | CAATTTCATCATTCATTCATTTCAgtttactagcagtccggttct | 5-139 | 2,991-3,505 | 3 | 21.5 |

| Lm3-4.VGCb5 (44) | TCATTTACCAATCTTTCTTTATACggtgtgttctctttaggggct | 97-336 | 2,475-2,997 | 2 | 7.4 |

| Lm3-4.VGCb6 (18) | TCAAAATCTCAAATACTCAAATCAgcaaaataagcgcaccggctt | −10 to 147 | 2,658-3,136 | 1 | 18.1 |

| Lm3-4.VGCb7 (97) | AATCTCATAATCTACATACACTATcaattgttgataaaagtgcaggga | 134-504 | 1,859-2,196 | 2 | 3.7 |

| Lm3-4.VGCb8 (30) | TTACCTTTATACCTTTCTTTTTACatgcttcggactttccacct | 59-1,071 | 10,699-11,430 | 1 | 10.0 |

| Lm3-4.VGCb9 (24) | TCAATTACCTTTTCAATACAATACgatatgccgagcctaccat | 89-459 | 4,224-4,322 | 1 | 9.2 |

| Lm3-4.VGCb10 (5) | CAATTCAAATCACAATAATCAATCgagcagccaagcgaggtaaac | 66-255 | 1,415-1,507 | 1 | 5.6 |

| Lm3-4.VGCb11 (16) | AATCAATCTTCATTCAAATCATCAagcgaggtaaatacgggaccg | −117 to 199 | 4,627-5,741 | 3 | 23.3 |

| Lm3-4.VGCb12 (46) | TACATCAACAATTCATTCAATACActagctgatttaagagatagg | 275-561 | 5,167-5,742 | 3 | 9.2 |

| Lm3-4.VGCb13 (80) | CTAACTAACAATAATCTAACTAACgaacaaactgagaatgcggcc | 12-182 | 6,160-7,025 | 1 | 33.9 |

| Lm3-4.VGCb14 (60) | AATCTACAAATCCAATAATCTCATcttcctatcacgaaagcacg | 22-208 | 2,986-3,392 | 1 | 14.3 |

| Lm3-4.VGCb15 (33) | TCAATTACTTCACTTTAATCCTTTagacttgctttgccagagacc | 97-612 | 5,032-5,259 | 1 | 8.2 |

| Lm3-4.VGCb16 (96) | ATACTAACTCAACTAACTTTAAACcataatatttgcaacgacagataa | 37-195 | 2,375-2,671 | 1 | 12.2 |

| Lm3-4.VGCb17 (55) | TATATACACTTCTCAATAACTAACcacagatgaatgggaagaagg | 103-315 | 4,468-4,926 | 1 | 14.2 |

| Lm3-4.VGCb18 (86) | CTAATTACTAACATCACTAACAATctggataaaccaacaaaagcaac | 7-148 | 3,477-3,936 | 1 | 23.6 |

| Lm3-4.VGCbx (50) | CAATATACCAATATCATCATTTACgacttagattctagcatgcagtc | N/A | 1,484-4,209 | 48 | N/A |

N/A, not applicable for positive control probes.

The 64 probes used in the lineage II assay are prefaced with Lm2, while the 51 probes used in the lineage III and IV assay are prefaced with Lm3-4. Luminex microsphere sets (Luminex Corporation) used for hybridization reactions are indicated in parentheses.

The 5′ sequence tag portions of extension probes are capitalized.

Target sample size among the 125 lineage II and 48 lineage III and IV strains sequenced.

ID, index of discrimination.

Biotinylated extension products from ASPE reactions were sorted via hybridization with fluorescent microspheres. Microspheres were coated with anti-tag sequences specific to the 5′ sequence tags appended to the extension probes. Hybridization reactions were performed in 50-μl volumes with 1× TM buffer (0.2 M NaCl, 0.1 M Tris, 0.08% Triton X-100; pH 8.0), 10 μl of extension product, and 625 microspheres from each set. The samples were incubated for 90 s at 96°C, followed by 45 min at 37°C. Microspheres were twice pelleted by centrifugation (3 min at 3,700 × g) and resuspended in 70 μl 1× TM buffer. Following these washes, microspheres were pelleted and resuspended in 70 μl 1× TM buffer containing 2 μg/ml streptavidin R-phycoerythrin. Samples were incubated for 15 min at 37°C prior to detecting the microsphere complexes with a Luminex 100 flow cytometer (Luminex Corporation).

The median fluorescence intensity (MFI) from biotinylated extension products attached to 100 polystyrene microspheres was adjusted to account for background fluorescence by subtracting the average MFI of three template-free controls from the MFI for each probe. Probe performance was assessed via the index of discrimination, defined as the ratio of the lowest target MFI to the highest nontarget MFI obtained in two independent runs of the sequenced isolate panels. Probes with a ratio less than 2.0 were redesigned. Critical values for discriminating between positive and negative alleles were set halfway between the lowest target MFI and the highest nontarget MFI observed among the sequenced isolates. In addition, positive control probes were designed to confirm the presence of each of the amplicons in the multiplex PCR. Minimum thresholds for positive control probes were set at 75% of the lowest MFI observed in the MLGT analysis of sequenced isolates.

Comparative subtyping.

The discriminatory power of MLGT was compared with PFGE and two recently described multilocus sequence typing methods (37, 50) using a panel of 20 human sporadic listeriosis isolates provided by L. Graves (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]). This independent panel of isolates was not used in SNP discovery or the design of MLGT probes. PulseNet pattern identifiers for AscI and ApaI were provided with the isolates. Multilocus sequencing was carried out as previously described (37, 50). DNA sequences were edited and analyzed as described above. Simpson's discrimination index (SDI) values were calculated as previously described (15). Comparative subtyping analysis for the lineage III and IV assay was not performed due to the rarity of these isolates.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

DNA sequences generated for this study were deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers FJ024725 to FJ025060 and FJ041118 to FJ041147.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

DNA sequence analysis.

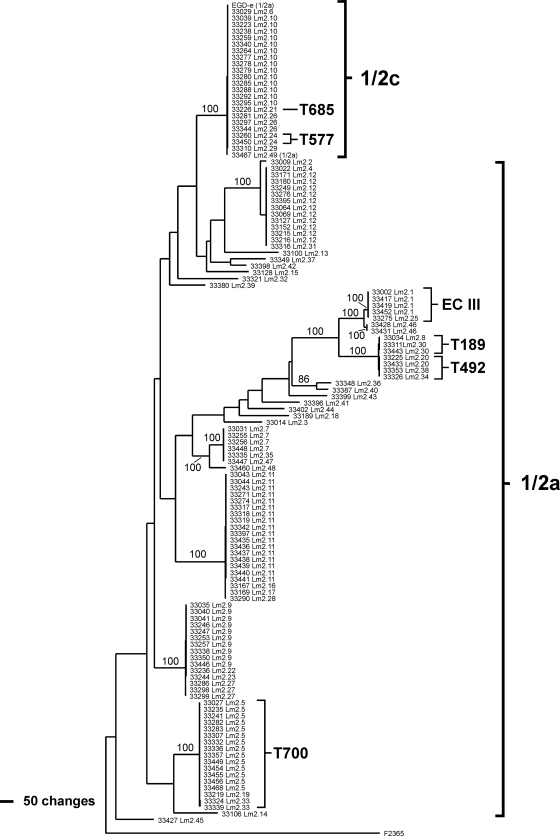

A database of 24,852 bp of aligned DNA sequence from each of 125 lineage II isolates (Table 1) was developed for SNP discovery. This database consisted of sequences from 12 regions of the L. monocytogenes genome and contained 1,419 SNPs (Table 3), as well as indel variation, which defined 56 unique multilocus sequence types (Table 1). Six sequence types were observed among the 22 isolates assigned via PCR analysis to serogroup 1/2c (includes serotype 1/2c and 3c isolates), while 50 unique sequence types were observed among the 103 isolates from serogroup 1/2a (includes serotype 1/2a and 3a isolates) (Table 1). There were no sequence types in common between the serogroup 1/2c and 1/2a isolates in Table 1, and phylogenetic analyses of the multilocus sequence data placed all serogroup 1/2c isolates within a single clade (Fig. 1). However, analysis of sequences from the reference strain EGD-e revealed that this serotype 1/2a strain had the same sequence type (ST2-10) as 14 isolates from serogroup 1/2c (Table 1). In addition, phylogenetic analyses placed NRRL B-33467, a serogroup 1/2a isolate, within the 1/2c clade (Fig. 1). Previous analyses using macroarrays revealed that EGD-e is an atypical strain of serotype 1/2a with a genome more similar to serotype 1/2c strains than to other 1/2a strains (2, 3). Our results indicate that NRRL B-33467 is a similarly atypical strain and suggest that the 1/2a serotype has multiple evolutionary origins or that the 1/2a serotype has been acquired by some strains with a 1/2c genomic background via genetic exchange. Excluding EGD-e and NRRL B-33467, the serogroup 1/2c isolates formed a monophyletic clade with 100% bootstrap support, while the serogroup 1/2a isolates constituted a highly diverse paraphyletic assemblage of strains that were genetically distinct from serogroup 1/2c strains (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

One of 20 most parsimonious trees inferred from analysis of the combined sequence data for the 125 lineage II isolates used in the SNP discovery (Table 1). Sequence data for strain EGD-e (NC_003210) were included for comparison, and the tree was rooted with sequence data from the lineage I strain F2365 (NC_002973). The frequency (percentage) with which a given branch was recovered in 2,000 bootstrap replications is shown above branches recovered in more than 70% of bootstrap replicates. With the exception of F2365 and EGD-e, strains are identified by NRRL-B numbers followed by MLGT subtype designations. Similar results were obtained with a neighbor-joining analysis.

The 125 lineage II isolates in Table 1 included two representatives of the previously described ECIII, which is the only lineage II epidemic clone described to date (20). NRRL B-33417 was implicated in a human listeriosis case associated with turkey franks in 1988, and NRRL B-33419 was associated with a multistate outbreak of listeriosis due to contaminated turkey deli meat in 2000. These isolates have an identical sequence type (ST2-1), which is consistent with previous evidence indicating they represent a strain that persisted in the same processing facility for more than a decade with minimal genetic change (20). Two additional food isolates (NRRL B-33002 and NRRL B-33452) with ST2-1 were identified among the 125 isolates examined. In addition, NRRL B-33275 had a sequence type (ST2-25) that differed from ST2-1 by only four substitutions out of the 24,852 bp of sequence analyzed (p-distance = 2 × 10−4), and it was considered a representative of the ECIII lineage on the basis of phylogenetic analyses (Fig. 1) and the phylogenetic definition of clonal lineages described by Ducey et al. (5).

Five unique mutations leading to premature stop codons in inlA were observed among 27 of the 125 lineage II isolates sequenced for SNP discovery (Tables 1 and 6). The inlA gene encodes a membrane-anchored invasion protein that interacts directly with host cell receptors to facilitate L. monocytogenes entry into nonprofessional phagocytes (14, 21). Previous studies documented that strains carrying mutations resulting in InlA truncations 5′ to the C-terminal LPXTG membrane-anchoring motif display virulence-attenuated phenotypes in animal models and a significantly reduced ability to invade human intestinal epithelial cells (17, 19, 25, 26, 29, 30, 39). All of the InlA truncation mutations observed in this study occurred 5′ to the LPXTG motif, and four of these five mutations were previously characterized (Table 6). However, we identified a novel mutation (T189) (Table 6) in three RTE meat isolates, which resulted in a predicted protein of only 189 amino acids. While the InlA truncation mutations were observed in strains from different parts of the lineage II phylogeny, little sequence variation was observed between isolates with the same truncation mutation (p-distance < 1.2 × 10−4), indicating that each of these mutations had a recent evolutionary origin (Fig. 1). Interestingly, strains carrying T189 or T492 mutations formed a monophyletic clade that was closely aligned with ECIII strains in the multigene phylogeny (Fig. 1), suggesting that closely related clonal lineages might have different virulence properties.

TABLE 6.

Mutations leading to truncated forms of InlA among 125 sequenced isolates from L. monocytogenes lineage II

| Mutationa | Equivalentb | MLGT probe(s)c | MLGT haplotype(s) | RTE (%)d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T189 | Lm2.INLa8, Lm2.INLa13 | Lm2.8, Lm2.30 | 3.9 | |

| T492 | H1 | Lm2.INLa9, Lm2.INLa14 | Lm2.20, Lm2.34, Lm2.38 | 3.9 |

| T577 | LO28 | Lm2.INLa11, Lm2.INLa15 | Lm2.24 | 2.6 |

| T685 | NV5 | Lm2.INLa10 | Lm2.21 | 0.0 |

| T700 | PMSC3 | Lm2.INLa7, Lm2.INLa12 | Lm2.5, Lm2.19, Lm2.33 | 20.8 |

Mutation nomenclature reflects the amino acid position of premature stop codons relative to the 800-amino-acid protein predicted for strain EGD-e (NC_003210).

Strain names or previous designations for equivalent mutations described by Jonquieres et al. (19), Olier et al. (29), Rousseaux et al. (39), and Nightingale et al. (26).

Four of the five truncation mutations were targeted by pairs of reciprocal probes, one of which was specific to the nucleotide character state responsible for the truncation, while the other probe was specific to the alternate form of the inlA allele. After multiple attempts, only a single acceptable probe was identified for the T685 mutation.

Frequency of InlA truncation mutations among 77 lineage II isolates collected by USDA-FSIS from RTE products and processing facilities.

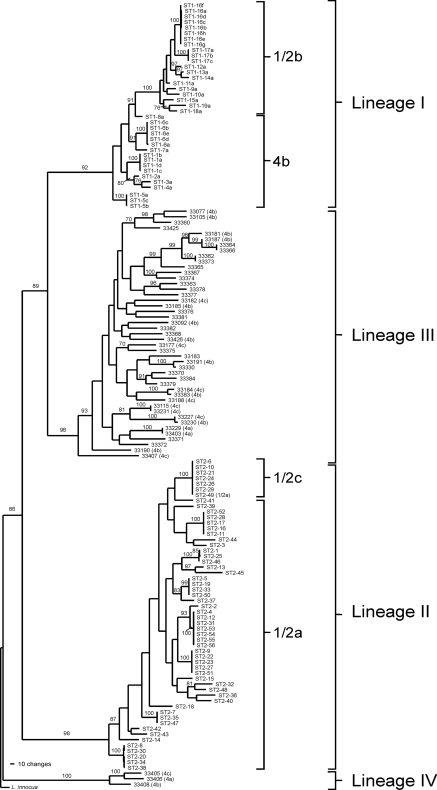

A comparative sequence database consisting of 14,881 bp of DNA sequence from 48 isolates was developed for SNP discovery within the rare lineages III and IV. The regions sequenced (VGC, LMO, and INL) contained 1,614 SNPs (Table 3), as well as indel variation that defined 44 multilocus sequence types among the 48 lineage III and IV isolates examined (Table 1). With the exception of a mutation leading to a single amino acid reduction in the predicted length of InlA among two of the lineage IV strains, there were no premature stop codons observed within the lineage III and IV sequences.

Phylogenetic analysis of VGC, LMO, and INL sequences confirmed previous reports (22, 33, 38) that lineage IV isolates are not part of a monophyletic lineage III and indicated that they represent an early divergence within L. monocytogenes (Fig. 2). While lineages III and IV are both polymorphic for serotypes 4a, 4c, and 4b, the results of the current analysis (Fig. 2) and previous phylogenetic analyses (33, 38) demonstrate that this shared serotype polymorphism is not the result of an exclusive shared ancestry. In addition, mapping serotype data onto the multigene phylogeny (Fig. 2) indicated that in contrast to lineages I and II, genetic variation within lineage III is not strongly partitioned in accordance with serotype divisions. Taken together, these results support the hypothesis that serotype polymorphism shared by lineages III and IV was derived independently from a serogroup 4 ancestor and is not a reliable indicator of evolutionary relatedness for these lineages. Alternatively, these results could be interpreted as indicating an inability of serotyping techniques to precisely differentiate among serotypes 4a, 4c, and 4b, as has been reported previously for serotypes 4b, 4d, and 4e within lineage I (34).

FIG. 2.

One of four most parsimonious trees inferred from analysis of sequences from the LMO, VGC, and INL regions (Table 3). The analysis included sequences from all 48 lineage III and IV isolates examined (identified by NRRL-B numbers) and unique sequence types identified in the SNP discovery for lineages I (5) and II (Table 1). The LMO sequence from Listeria innocua strain Clip11262 (NC_003212) was used to root the tree. The frequency (percentage) with which a given branch was recovered in 2,000 bootstrap replications is shown above branches recovered in more than 70% of bootstrap replicates. Similar results were obtained with neighbor-joining analysis.

Design and validation of the MLGT assays.

In order to develop single-well assays for the rapid and accurate discrimination of lineage II, III, and IV subtypes, variation identified in the comparative sequence analysis (Table 3) was used to design multilocus genotyping probes from the seven genomic regions listed in Table 4. All three of the regions sequenced for SNP discovery within lineages III and IV (Table 3) were included in a combined lineage III and IV MLGT assay (Table 4), which identified all 44 unique haplotypes among the 48 lineage III and IV isolates sequenced. However, in order to optimize the performance of the multiplex PCR while providing maximal haplotype discrimination, the lineage II MLGT was focused on the seven amplicons listed in Table 4. This single-well assay differentiated 49 unique haplotypes among the 125 lineage II isolates in Table 1. Each of the regions listed in Table 3 that were excluded from the lineage II MLGT assay differentiated no more than one additional haplotype, with the exception of PDH, which differentiated two novel haplotypes.

The lineage II MLGT assay consisted of 64 probes, which included seven positive control probes designed to confirm the presence of each of the amplicons in the multiplex PCR (Table 4). The MLGT assay for lineages III and IV consisted of 51 probes, which included positive control probes for each of five amplicons (Table 4). Probe sequences and probe performance data are provided in Table 5. The index of discrimination values for the MLGT probes ranged from 2.4 to 73.7 with a mean of 14.0. This means that the fluorescence intensities (MFI values) for isolates with a positive allele were always more than twice as high, and on average 14 times as high, as background values for isolates with a negative allele. Replicate runs of the 173 sequenced isolates produced identical results, demonstrating the reproducibility of MLGT data and the ability of the MLGT assays to type all of the tested isolates. In addition, the single-well MLGT assays recovered 93% of the 100 haplotypes defined by the full DNA sequence data set (>3.8 Mb) described in Table 3 and 100% of the haplotypes defined by more than 2.5 Mb of comparative DNA sequence data from the regions incorporated into the assays (Table 4). Probe patterns for unique haplotypes are provided in Table S1 of the supplemental material.

The 10,448 MLGT genotypes derived from the 115 total probes utilized in the assays were consistent with DNA sequence data for the 173 sequenced isolates. Isolates from the previously linked listeriosis case associated with turkey franks in 1988 and a multistate outbreak in 2000 had identical MLGT patterns (Lm2.1), demonstrating good epidemiological concordance. In addition, MLGT types were not shared in common between serogroup 1/2a and 1/2c isolates that we tested, indicating that MLGT type could provide accurate information about major serogroup identity for most lineage II isolates. Serotype prediction based on MLGT may not be possible among lineage III isolates or in rare instances in which serotype 1/2a strains have a predominately 1/2c genome (Fig. 1). However, this results from a poor correlation between genomic and antigenic variation and does not reflect a failure of MLGT to accurately characterize the genomic background of these strains.

Phylogenetic trees inferred via analyses of genotype data from the lineage II and the lineage III and IV MLGT assays (not shown) were largely congruent with phylogenies based on multilocus DNA sequence data (Fig. 1 and 2). Interior branches in the MLGT trees were not strongly supported by bootstrap analysis, and additional probe design may be required to improve phylogenetic resolution. However, because there is a direct connection between MLGT subtypes and the underlying DNA sequence data, MLGT data can be mapped onto the multilocus DNA sequence tree (Fig. 1), allowing the phylogenetic information provided by the large comparative sequence databases to be integrated with MLGT results.

Subtype prevalence in RTE food.

Of the 173 lineage II, III, and IV isolates used in the design and validation of the MLGT assays (Table 1), 94 were collected by the USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) from RTE foods and food-processing facilities. We excluded isolates collected on the same day from the same state, as well as isolates lacking information on date of isolation in order to minimize duplicate sampling. This produced a set of 78 FSIS isolates with which we evaluated subtype frequencies (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Only one lineage III isolate was observed in this panel, while the remaining 77 isolates were identified as lineage II. Thirty unique MLGT haplotypes were observed among these 77 lineage II isolates, indicating substantial diversity within the FSIS panel. Of these, 21 MLGT types from 59 (76.6%) lineage II isolates corresponded to serogroup 1/2a, and 5 MLGT types from 18 (23.4%) isolates corresponded to serogroup 1/2c. The FSIS isolate NRRL B-33452 had the same MLGT type (Lm2.1) as the strain responsible for the multistate outbreak of listeriosis in 2000. This was the only isolate with an ECIII-associated MLGT type among the FSIS isolate panel. Combining these results with data used to determine the frequency of lineage I epidemic clones (5) indicates that strains from epidemic clone groups were rare (6.3% of 144 isolates) in RTE food products and processing facilities sampled by FSIS.

Conversely, MLGT analysis demonstrated that strains with mutations leading to truncated forms of the key virulence determinant, InlA, comprised at least 31.2% of the lineage II isolates recovered from RTE food and food-processing facilities monitored by FSIS. The lineage II MLGT contained probes for each of the InlA truncation mutations identified among the sequenced isolates, and we observed four of these five mutation types among the FSIS isolate panel (Table 6). The most common truncation mutation (T700) was identified in 16 (20.8%) of the FSIS isolates, while the other truncation types were observed at less than 4% frequency (Table 6). The results for T700 are consistent with a previous estimate of the frequency (11.2%) of ribotype patterns associated with this mutation among food isolates (26). However, frequency estimates for the other lineage II truncation types among food isolates have not been previously investigated. Despite the fact that each of the InlA truncation mutations examined had a single and recent evolutionary origin (Fig. 1), three of the five InlA truncation types in Table 6 were differentiated into multiple MLGT types (Table 6), and at least two mutation types are associated with multiple serotypes from the same major serogroup (Table 1). Therefore, it is clear that some level of genetic and antigenic divergence or exchange has occurred since these truncation mutations were introduced into their respective clonal lineages.

Combining information from the FSIS panel with previously published data from a similar panel of lineage I isolates (5), we estimate that at least 30% of all L. monocytogenes isolates obtained from FSIS surveillance of RTE foods and food-processing facilities carry mutations leading to truncated forms of InlA. In addition, this is likely to represent a conservative estimate of the InlA truncation frequency among food isolates because it is based only on the mutations that were observed in our SNP discovery. These results support and extend previous hypotheses that a substantial fraction of L. monocytogenes isolates from foods have reduced abilities to cause systemic listeriosis (5, 26). However, this does not imply that strains with InlA truncation mutations pose no threat to public health. While rare, such strains have been obtained from human and animal listeriosis cases (13, 26, 27), and different InlA truncation types have been associated with different levels of virulence attenuation in animal models (29, 30). In addition, the precise contribution of InlA truncations to attenuated virulence phenotypes needs to be more conclusively defined (5, 26, 28).

The fact that multiple independent mutations leading to InlA truncations have been identified within lineages I and II led to the suggestion that positive selection has driven the loss of functional or cell wall-anchored InlA, particularly among isolates from food environments (26, 32). However, no specific adaptive advantage responsible for the hypothesized positive selection has been identified (32). In addition, the observations regarding InlA truncation frequencies among food isolates could result from food and food-processing facilities providing permissive environments in which there should be little or no selective constraint to eliminate mutations that disrupt the function or cell wall association of an invasion protein such as InlA. Ecological success of inlA alleles carrying truncation mutations could be indirect evidence of an adaptive advantage (26). However, many of the InlA truncation mutations were found at low frequencies in surveys of food isolates (Table 6) (5, 26), and it is not clear if the mutations leading to truncated forms of InlA represent the cause or the effect of successful colonization of food-processing environments. This is not to suggest that the positive selection hypothesis should be rejected but highlights the need to consider environment-specific relaxation of constraints as an alternative explanation.

Regardless of the nature of selection acting on inlA alleles harboring truncation mutations, there is clearly an association between subtype prevalence in food environments and the subtype distribution of InlA truncation mutations. The InlA truncation mutations identified to date are restricted to serogroups 1/2a and 1/2c from lineage II and serogroup 1/2b from lineage I (5, 19, 26, 29, 32, 39). These are the most common subtypes isolated from foods and food-processing environments (5, 13, 46). As such, it is reasonable to expect that variation within these groups is shaped to a greater extent by selective constraints operating in food environments than is the case for strains from serogroup 4b of lineage I, or lineage III strains, both of which are relatively rare in food environments (5, 13, 41, 46). The relative rarity of serogroup 4b (lineage I) and lineage III strains in food environments could explain the absence of InlA truncation mutations in these groups, which in turn could contribute directly to their overrepresentation in human and animal listeriosis cases, respectively.

Comparative subtype analysis.

The discriminatory power of the MLGT assay for lineage II was compared to that of PFGE, the six-gene multilocus sequence typing (MLST) approach described by Revazishvilli et al. (37), and the multi-virulence locus sequence typing (MVLST) approach described by Zhang et al. (50). In an analysis of 20 sporadic listeriosis isolates provided by the CDC (Table 2), the lineage II MLGT provided the greatest discriminatory power (12 haplotypes; SDI, 0.93) among the DNA sequence-based approaches. SDI values are scored between 0 and 1, and SDI values above 0.9 are considered desirable for reliable subtyping (15). MVLST utilized 2,750 bp of DNA sequence from each of the 20 isolates and differentiated 10 sequence types (SDI, 0.88). MLST based on 4,322 bp of DNA sequence from each isolate identified 11 sequence types (SDI, 0.91) but utilized amplicons that were too large to be sequenced using the amplification primers, necessitating the design and use of several internal sequencing primers. In addition, the pgm primers used in the MLST produced small nontarget amplicons that prevented us from sequencing with the amplification primers, and the region of actA targeted by MLST included a 105-bp indel polymorphism that could make it impossible to assess positional homology.

As was the case in our previous analysis of lineage I isolates (5), PFGE provided greater strain-discriminating power (17 types; SDI, 0.98) than the DNA sequence-based approaches (Table 2). Combining data from MLGT, MLST, and MVLST provided a modest increase in discriminatory power (13 types; SDI, 0.94) above that provided by MLGT alone but still did not discriminate all of the strains that had unique PFGE patterns. Similarly, PFGE provided greater discriminatory power than a recently published method based on multiple-locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis (MLVA) (42). This suggests that there may be practical limitations to the development of locus-specific methods for DNA sequence-based subtyping of L. monocytogenes that achieve the level of discrimination provided by two-enzyme PFGE. However, DNA sequence-based methods offer solutions to many of the problems and limitations of PFGE described above, which make them attractive options for complementing or replacing PFGE as the primary subtyping tool for L. monocytogenes (5, 11, 16, 37, 43, 50). In addition, while PFGE has been reported to have the highest discriminatory power, it does not always discriminate between related but distinct strains (5, 40, 45). In our comparative analyses of typing methods, only the MLGT method differentiated strains with identical PFGE patterns. NRRL B-33575 and NRRL B-33578 shared identical PFGE, MLST, and MVLST patterns but were differentiated by MLGT because NRRL B-33578 harbors the T577 mutation in inlA that is associated with a weak attenuation of virulence in animal models (29, 30). This result demonstrates the potential for MLGT to complement PFGE data in strain discrimination and highlights the fact that strains with identical PFGE patterns can harbor differences in key virulence genes.

Combined with our previously developed MLGT assay for subtyping lineage I isolates (5), the MLGT assays described here provide a highly flexible and efficient system for DNA sequence-based subtyping of L. monocytogenes. These single-well assays provide high-throughput subtyping via direct interrogation of SNPs from multiple regions of the genome and produce data that are unambiguous, easily shared between laboratories, and amenable to phylogenetic analyses and risk assessment. Similar assays for detection and subtyping of food-borne pathogens have been described (6, 9) or are under development (16), indicating that SNP-based subtyping may offer a common approach for future subtyping of food-borne and other pathogens.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Lewis Graves and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for providing clinical isolates and PFGE patterns and to Kitty Pupedis and the USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service for providing isolates. We thank Jennifer Steele for excellent technical assistance. We also thank Brent Page and Peter Evans for helpful advice and discussions.

The mention of firm names or trade products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the U.S. Department of Agriculture over other firms or similar products not mentioned.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 17 October 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Borucki, M. K., S. H. Kim, D. R. Call, S. C. Smole, and F. Pagotto. 2004. Selective discrimination of Listeria monocytogenes epidemic strains by a mixed-genome DNA microarray compared to discrimination by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, ribotyping, and multilocus sequence typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:5270-5276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doumith, M., C. Buchrieser, P. Glaser, C. Jacquet, and P. Martin. 2004. Differentiation of the major Listeria monocytogenes serovars by multiplex PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:3819-3822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doumith, M., C. Cazalet, N. Simoes, L. Frangeul, C. Jacquet, F. Kunst, P. Martin, P. Cossart, P. Glaser, and C. Buchrieser. 2004. New aspects regarding evolution and virulence of Listeria monocytogenes revealed by comparative genomics and DNA arrays. Infect. Immun. 72:1072-1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doumith, M., C. Jacquet, V. Goulet, C. Oggioni, F. Van Loock, C. Buchrieser, and P. Martin. 2006. Use of DNA arrays for the analysis of outbreak-related strains of Listeria monocytogenes. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 296:559-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ducey, T. F., B. Page, T. Usgaard, M. K. Borucki, K. Pupedis, and T. J. Ward. 2007. A single-nucleotide-polymorphism-based multilocus genotyping assay for subtyping lineage I isolates of Listeria monocytogenes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:133-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunbar, S. A., and J. W. Jacobson. 2007. Quantitative, multiplexed detection of Salmonella and other pathogens by Luminex xMAP suspension array. Methods Mol. Biol. 394:1-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farber, J. M., and P. I. Peterkin. 1991. Listeria monocytogenes, a food-borne pathogen. Microbiol. Rev. 55:476-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Felsenstein, J. 1985. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39:783-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fitzgerald, C., M. Collins, S. van Duyne, M. Mikoleit, T. Brown, and P. Fields. 2007. Multiplex, bead-based suspension array for molecular determination of common Salmonella serogroups. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:3323-3334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fugett, E., E. Fortes, C. Nnoka, and M. Wiedmann. 2006. International Life Sciences Institute North America Listeria monocytogenes strain collection: development of standard Listeria monocytogenes strain sets for research and validation studies. J. Food Prot. 69:2929-2938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerner-Smidt, P., K. Hise, J. Kincaid, S. Hunter, S. Rolando, E. Hyytia-Trees, E. M. Ribot, and B. Swaminathan. 2006. PulseNet USA: a five-year update. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 3:9-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gravesen, A., T. Jacobsen, P. L. Moller, F. Hansen, A. G. Larsen, and S. Knochel. 2000. Genotyping of Listeria monocytogenes: comparison of RAPD, ITS, and PFGE. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 57:43-51. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gray, M. J., R. N. Zadoks, E. D. Fortes, B. Dogan, S. Cai, Y. Chen, V. N. Scott, D. E. Gombas, K. J. Boor, and M. Wiedmann. 2004. Listeria monocytogenes isolates from foods and humans form distinct but overlapping populations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:5833-5841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamon, M., H. Bierne, and P. Cossart. 2006. Listeria monocytogenes: a multifaceted model. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4:423-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunter, P. R., and M. A. Gaston. 1988. Numerical index of the discriminatory ability of typing systems: an application of Simpson's index of diversity. J. Clin. Microbiol. 26:2465-2466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hyytiä-Trees, E. K., K. Cooper, E. M. Ribot, and P. Gerner-Smidt. 2007. Recent developments and future prospects in subtyping of foodborne bacterial pathogens. Future Microbiol. 2:175-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacquet, C., M. Doumith, J. I. Gordon, P. M. Martin, P. Cossart, and M. Lecuit. 2004. A molecular marker for evaluating the pathogenic potential of foodborne Listeria monocytogenes. J. Infect. Dis. 189:2094-2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jeffers, G. T., J. L. Bruce, P. L. McDonough, J. Scarlett, K. J. Boor, and M. Wiedmann. 2001. Comparative genetic characterization of Listeria monocytogenes isolates from human and animal listeriosis cases. Microbiology 147:1095-1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jonquieres, R., H. Bierne, J. Mengaud, and P. Cossart. 1998. The inlA gene of Listeria monocytogenes LO28 harbors a nonsense mutation resulting in release of internalin. Infect. Immun. 66:3420-3422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kathariou, S. 2003. Foodborne outbreaks of listeriosis and epidemic-associated lineages of Listeria monocytogenes. Iowa State University Press, Ames.

- 21.Lecuit, M., S. Vandormael-Pournin, J. Lefort, M. Huerre, P. Gounon, C. Dupuy, C. Babinet, and P. Cossart. 2001. A transgenic model for listeriosis: role of internalin in crossing the intestinal barrier. Science 292:1722-1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu, D., M. L. Lawrence, M. Wiedmann, L. Gorski, R. E. Mandrell, A. J. Ainsworth, and F. W. Austin. 2006. Listeria monocytogenes subgroups IIIA, IIIB, and IIIC delineate genetically distinct populations with varied pathogenic potential. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:4229-4233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McClure, P. J., T. M. Kelly, and T. A. Roberts. 1991. The effects of temperature, pH, sodium chloride and sodium nitrite on the growth of Listeria monocytogenes. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 14:77-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mead, P. S., L. Slutsker, V. Dietz, L. F. McCaig, J. S. Bresee, C. Shapiro, P. M. Griffin, and R. V. Tauxe. 1999. Food-related illness and death in the United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 5:607-625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nightingale, K. K., R. A. Ivy, A. J. Ho, E. D. Fortes, B. L. Njaa, R. M. Peters, and M. Wiedmann. 2008. inlA premature stop codons are common among Listeria monocytogenes isolated from foods and yield virulence-attenuated strains that confer protection against infection by fully virulent L. monocytogenes strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:6570-6583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nightingale, K. K., K. Windham, K. E. Martin, M. Yeung, and M. Wiedmann. 2005. Select Listeria monocytogenes subtypes commonly found in foods carry distinct nonsense mutations in inlA, leading to expression of truncated and secreted internalin A, and are associated with a reduced invasion phenotype for human intestinal epithelial cells. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:8764-8772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nightingale, K. K., K. Windham, and M. Wiedmann. 2005. Evolution and molecular phylogeny of Listeria monocytogenes isolated from human and animal listeriosis cases and foods. J. Bacteriol. 187:5537-5551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olier, M., D. Garmyn, S. Rousseaux, J. P. Lemaitre, P. Piveteau, and J. Guzzo. 2005. Truncated internalin A and asymptomatic Listeria monocytogenes carriage: in vivo investigation by allelic exchange. Infect. Immun. 73:644-648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olier, M., F. Pierre, J. P. Lemaitre, C. Divies, A. Rousset, and J. Guzzo. 2002. Assessment of the pathogenic potential of two Listeria monocytogenes human faecal carriage isolates. Microbiology 148:1855-1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olier, M., F. Pierre, S. Rousseaux, J. P. Lemaitre, A. Rousset, P. Piveteau, and J. Guzzo. 2003. Expression of truncated internalin A is involved in impaired internalization of some Listeria monocytogenes isolates carried asymptomatically by humans. Infect. Immun. 71:1217-1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olsen, S. J., M. Patrick, S. B. Hunter, V. Reddy, L. Kornstein, W. R. MacKenzie, K. Lane, S. Bidol, G. A. Stoltman, D. M. Frye, I. Lee, S. Hurd, T. F. Jones, T. N. LaPorte, W. Dewitt, L. Graves, M. Wiedmann, D. J. Schoonmaker-Bopp, A. J. Huang, C. Vincent, A. Bugenhagen, J. Corby, E. R. Carloni, M. E. Holcomb, R. F. Woron, S. M. Zansky, G. Dowdle, F. Smith, S. Ahrabi-Fard, A. R. Ong, N. Tucker, N. A. Hynes, and P. Mead. 2005. Multistate outbreak of Listeria monocytogenes infection linked to delicatessen turkey meat. Clin. Infect. Dis. 40:962-967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orsi, R. H., D. R. Ripoll, M. Yeung, K. K. Nightingale, and M. Wiedmann. 2007. Recombination and positive selection contribute to evolution of Listeria monocytogenes inlA. Microbiology 153:2666-2678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Orsi, R. H., Q. Sun, and M. Wiedmann. 2008. Genome-wide analyses reveal lineage specific contributions of positive selection and recombination to the evolution of Listeria monocytogenes. BMC Evol. Biol. 8:233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]