Abstract

We established a technique for efficiently generating large chromosomal deletions in the koji molds Aspergillus oryzae and A. sojae by using a ku70-deficient strain and a bidirectional marker. The approach allowed deletion of 200-kb and 100-kb sections of A. oryzae and A. sojae, respectively. The deleted regions contained putative aflatoxin biosynthetic gene clusters. The large genomic deletions generated by a loop-out deletion method (resolution-type recombination) enabled us to construct multiple deletions in the koji molds by marker recycling. No additional sequence remained in the resultant deletion strains, a feature of considerable value for breeding of food-grade microorganisms. Frequencies of chromosomal deletions tended to decrease in proportion to the length of the deletion range. Deletion efficiency was also affected by the location of the deleted region. Further, comparative genome hybridization analysis showed that no unintended deletion or chromosomal rearrangement occurred in the deletion strain. Strains with large deletions that were previously extremely laborious to construct in the wild-type ku70+ strain due to the low frequency of homologous recombination were efficiently obtained from Δku70 strains in this study. The technique described here may be broadly applicable for the genomic engineering and molecular breeding of filamentous fungi.

Techniques for generating large chromosomal deletions are crucial for functional genomics studies and for the breeding of organisms. Microorganisms employed in the process of manufacturing commonplace materials sometimes retain a genomic region responsible for the pathogenic or toxic properties. Genes lying within such regions may be expressed only in certain strains or under a narrow range of conditions. The potential risk posed by these detrimental genes can be eliminated if selectively deleted. Therefore, it is desirable to establish a general technique for eliminating unfavorable genomic regions from chromosomes of industrially important microorganisms. However, low frequencies of homologous recombination can hamper such procedures. This is particularly problematic in the wild-type strains of industrially used microorganisms (27, 19).

The koji molds Aspergillus oryzae and A. sojae, used for the industrial production of enzymes and oriental fermented foods, are recognized as biologically safe host organisms. Indeed, the FDA has designated the koji molds GRAS (generally recognized as safe) (6, 17). Thus, these molds are among the most useful filamentous fungi. Aflatoxins (AFs) are potent carcinogenic metabolites mainly produced by the pathogenic fungal species Aspergillus flavus and A. parasiticus. Neither A. oryzae nor A. sojae produces AFs. They do, however, contain a remnant region within their genomes that is associated with the biosynthesis of AFs. This region is genetically inactive (6, 28, 29). Moreover, the complete genome sequence of A. oryzae (17) has revealed additional gene clusters suspected of being related to the production of mycotoxins other than AFs. It has been confirmed that the industrially used koji mold strains do not produce any toxigenic products such as mycotoxins. Nonetheless, the potential risk associated with the production of such toxins could be completely eliminated by deleting the genetic remnants from the genome. Toward this goal, it is crucial to establish a general method for generating chromosomal deletions in the koji molds.

Thus far, the construction of koji mold strains with a deleted AF gene cluster has been unsuccessful, partly due to inefficient homologous recombination (27). Recently, we reported that koji mold strains with disrupted alleles in the ku70 and ku80 genes exhibit markedly increased frequencies of homologous recombination (21, 26). These genes are involved in nonhomologous end joining and play a crucial role in the repair of DNA double-strand breaks (7).

Techniques for generating chromosomal deletions and the mechanism of recombination in bacteria and in Saccharomyces cerevisiae have been intensively studied. The Cre-loxP site-specific recombination system provides a powerful tool for constructing specific chromosomal regions in a number of organisms, such as bacterial, yeast, plant, and mammalian cells (10, 24, 25). This system is based on a loop-out-type deletion method involving recombination at a specific loxP site mediated by Cre derived from bacteriophage P1 (1). The Cre-loxP system may not be suitable for studies of food-grade microorganisms, because a loxP sequence remains in the chromosome after deletion is complete. Moreover, the existence of possible pseudo-loxP sites in the chromosomes has been reported to be an unexpected cause of mutations (16).

Chromosomal deletions can also be generated by loop-out-type recombination mediated by the bidirectional marker Ura3 and 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) in yeast (12, 13). Deletions of hundreds of kilobases in fission yeast have been demonstrated by using this system (11). The targeting efficiency of the system originally developed for S. cerevisiae is extremely high compared to that of filamentous fungal strains. Nevertheless, the system has been successfully adapted to filamentous fungi (8, 26). Short deletions have been obtained using a pyrG marker and 5-FOA selection in koji molds (26). In general, the koji molds exhibit a low frequency of homologous recombination. Furthermore, there have been no reports of large chromosomal deletions in relevant strains. Difficulties applying this system to the koji molds may be related to low frequencies of homologous recombination mediated by 5-FOA resistance.

Our recent studies have revealed that the ku-deficient koji mold strains have significantly higher targeting frequency than the ku-proficient strains (26). This prompted us to establish a method for generating large chromosomal deletions using ku-deficient koji mold strains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal strains, culture media, and transformation.

The fungal strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Polypeptone dextrin (PD) medium containing 1% polypeptone, 2% dextrin, 0.5% KH2PO4, 0.1% NaNO3, 0.05% MgSO4, and 0.1% Casamino Acids (pH 6.0) was used for liquid cultivation of the Aspergillus strains. Czapek-Dox (CZ) minimal medium plates containing 20 mM uridine and 5-FOA (2 mg/ml; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) were used for the positive selection of pyrG-deficient strains. Protoplast transformation of Aspergillus strains was carried out according to a previously described method (27). The transformants obtained on regeneration plates (1.2 M sorbitol-CZ) were transferred to and selected on CZ plates for further analysis.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this experiment

| Strain | Original strain name | Genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| I-6 | Aspergillus sojae ATCC 46250 | ΔpyrG wh− (the coding region of pyrG was deleted by replacement) | 27 |

| Askuptr8 | I-6 | Δku70::ptrA ΔpyrG wh− | 26 |

| RkuN16ptr1 | Aspergillus oryzae RIB40 (ATCC 42149) | Δku70::ptrA ΔpyrG | 26 |

| AskuptrP2-8 | Askuptr8 | Δku70::ptrA wh− | This study |

| Asvb19 | I-6 | wh− (bearing pkvb-PG2 at the pksA site) | This study |

| RkuptrP2-1 | RkuN16ptr1 | Δku70::ptrA (bearing pkvb-PG2 at the pksA site) | This study |

| Rku7C-3 | RkuN16ptr1 | Δku70::ptrA (bearing p7C-3 at the pksA site) | This study |

| Rku7C-4 | RkuN16ptr1 | Δku70::ptrA (bearing p7C-4 at the pksA site) | This study |

Information on the A. oryzae genome was obtained from the database of the genomes analyzed at the National Institute of Technology and Evaluation (http://www.bio.nite.go.jp/dogan/Top).

DNA techniques, PCR method, and Southern hybridization.

Genomic DNA of Aspergillus was prepared using a previously described method (27). PCR amplification was carried out with a GeneAmp 9600 thermocycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Southern hybridization was performed according to a previously described method (27). Digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled probes were constructed using a DIG PCR labeling kit (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Hybridization and detection of signals were carried out using a DIG system according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche Diagnostics). DIG-labeled probes, namely, pksA (C9; AO090026000009), moxY (C30; AO090026000009), C48 (AO090026000048), and C77 (AO09002600077), were constructed using the following primer pairs, respectively: pkU-pkL, moxU-moxL, C48U-C48L, and C121U-C121L. The oligonucleotide primers used in this experiment are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this experiment

| Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|

| pkdelU | ACGGCTTCGGCGTTACCTCGTTCAACC |

| pkdelL | TGGTGCATGGCGATGTGGTAGTTCTGG |

| PyrU | AGATCTGGTAATGTGCCCCAGGCTTGTCAG |

| PyrL | AGATCTTTTCCCACAGGTTGGTGCTAGTC |

| pk4400L | TGTCCGAGCAGACGGTGCTAATCATT |

| pk4500U | ATCGGGACCAAATTCCGTCCGCTTCT |

| 7C3U | TCAGTTGCGAAGGAGGGATTTATGGA |

| 7C3L | TTGTTCGGACTTGGGGGTTTGGGATTTA |

| 7C4U | GTAGCAATGGTCATATAAACGAGCGA |

| 7C4L | AGTGATATGATTGGACTGCTCTAGGG |

| AF2008U | CGCGGATAGGAAAAGGTGAGATCTATCTTC |

| AFJ2446L | GCCAACCCGATGCCTGATGCACCA |

| PkU | TATCTCGGAAGGATGTTAACGGCCT |

| PkL | TCAGGTGAGTTCTAAGGACATACCCA |

| moxU | CAACCTCCTCGGGGCCGATGAGCAC |

| moxL | CCTGGTCCTCGATGGCCTTTGCGTG |

| C48U | GGCCGTGTGCCTCTATTATAACAG |

| C48L | CCCGTCAAAAGCCAACAGAATAGA |

| C77U | GTCGGCAAACAATGAGACAGCCTCTT |

| C77L | AGATGTTGCTGAATCAGGGTGCCATT |

Construction of vectors for generating large deletions.

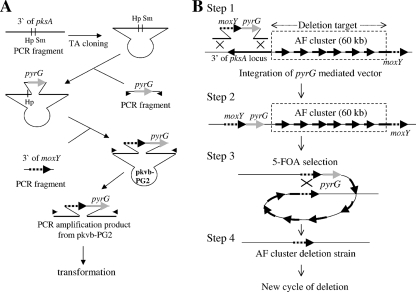

Vectors for entire AF cluster deletion (from pksA to moxY; 60 kb) by 5-FOA selection (loop-out method) were constructed using PCR and a TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen) as follows (Fig. 1A). PCR for TA cloning was carried out using Ex Taq polymerase (Takara); in all other PCR amplifications, KOD polymerase (Toyobo) was used. A 3-kb fragment containing the 3′ end of the pksA gene was amplified from A. sojae genomic DNA by using the primer pair pkdelU-pkdelL and cloned using the TOPO TA cloning kit. The resultant plasmid was digested with SmaI, dephosphorylated, ligated to a 2.7-kb pyrG fragment amplified from genomic DNA of A. sojae by using the primer pair pyrU-pyrL, and phosphorylated with polynucleotide kinase. A 1.7-kb fragment containing moxY was amplified from genomic DNA of A. sojae by using the primer pair moxU-moxL. The amplicon was cloned into the HpaI site of the plasmid to generate the AF deletion (60-kb deletion) vector pkvb-PG2. The vectors for the 100-kb (p7C-3) and 200-kb (p7C-4) deletions were constructed by exchanging the moxY fragment with fragments for 100-kb and 200-kb deletions, respectively. A 9.5-kb fragment amplified from pkvb-PG2 by using primer pair pk4400L-pk4500U was ligated to phosphorylated 2-kb fragments amplified from A. oryzae genomic DNA by using the primer pairs 7C3U-7C3L and 7C4U-7C4L, thereby generating the deletion vectors p7C-3 and p7C-4, respectively.

FIG. 1.

Strategy for generation of an AF biosynthetic gene cluster deletion strain by use of the loop-out (5-FOA selection) method. (A) Schematic representation of the construction of a vector for AF cluster deletion. Hp, HpaI site; Sm, SmaI site. Small arrowheads in the figure indicate the positions of oligonucleotide primers. (B) Generation of an AF cluster deletion strain. (Step 1) A 60-kb length of the AF cluster is the deletion target. The deletion vector of the AF cluster consisting of the pyrG marker and a DNA fragment homologous to the adjacent distal region of the AF cluster were transformed into cells of the koji mold. (Step 2) The deletion vector was integrated into the proximal adjacent region of the AF cluster. (Step 3) The cells from which pyrG was lost, as a result of the recombination between distal and proximal homologous regions adjacent to the AF cluster, were selected by 5-FOA resistance. (Step 4) AF cluster deletion was achieved.

A vector for the deletion of half of the AF cluster (from pksA to aflR; 30 kb) was constructed as follows. An 8-kb fragment containing an aflR-targeting construct was amplified from genomic DNA of A. sojae transformant AF74-9 (26) by using the primer pair AF2008U-AFJ2446L. In the AF74-9 transformant, the 3′ half of aflR was replaced with pyrG, which resulted from integration of the aflR-targeting vector pAfPX1 (27). The 8-kb amplified fragment was cloned using the TOPO TA cloning kit, and the 8-kb NotI-SpeI fragment was subcloned into the NotI-SpeI site of pBluescript KS, thereby generating pAFBlue. The pAFBlue plasmid was digested with SphI, dephosphorylated, and then ligated to a 1.8-kb SphI-digested fragment amplified using the primers pk4-4F2 and pksLT2 from A. sojae genomic DNA, thus yielding the vector for the deletion of half of the AF cluster, pAFpk-sph2.

Comparative genomic hybridization.

Ten micrograms of A. oryzae (5-FOA-resistant strain no. 2) genomic DNA partially digested with Sau3AI at 37°C for 1 min was electrophoresed on 1% agarose gel. Approximately 0.4- to 8-kb DNA fragments were recovered from the gel by using Wizard SV gel and a PCR cleanup system (Promega, Madison, WI) and concentrated by ethanol precipitation. Approximately 3 μg of the DNA fragments was fluorescently labeled with 0.1 mM Cy3/Cy5-dUTP in 50 μl of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) containing 7 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM dithiothreitol, 5 μg random hexamers, and a 20-U Klenow fragment at 25°C overnight and subjected to purification by using a GFX CyScribe purification kit (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) after addition of 12.5 μl 0.5 M EDTA.

The labeled DNA fragments were hybridized with the probes on the A. oryzae oligonucleotide 12k DNA microarray (MOASPOR-12000-1/2) (Fermlab, Tokyo, Japan). After hybridization at 42°C for overnight, the array slide was washed at room temperature using the slide washer SW-4 (Juuji Field, Tokyo, Japan) in a solution containing 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) and 0.03% sodium dodecyl sulfate for 15 min, then in a solution containing 0.2× SSC for 5 min, and finally in a solution containing 0.05× SSC for 5 min. After removal of the remaining buffer, the DNA microarray slide was scanned by a GenePix 4000B scanner (Axon Instruments/Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Spots of the scanned microarray images were automatically identified by GenePix Pro 6.0 software (Axon Instruments/Molecular Devices) with the settings “Find circular features,” “Resize features during alignment” (60 to 200% diameter), and “Limit feature movement during alignment” (40 μm). The fluorescence intensities of the two dyes, namely, Cy3 and Cy5, for reference and experimental DNAs, respectively, were calculated for each spot. The resulting data files were imported into GeneSpring GX 7.3.1 software (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) for further data analysis. The dye swap data files for each experiment were merged, and average spot intensities were used to reduce experimental bias. The normalizations were performed on merged data by locally weighted scatter plot smoothing normalization with default parameter settings, in which spots of reference DNA fluorescence intensity over 0.01 on data from both microarray experiments were used. The array data are available at the Computational Biology Research Center (CBRC Aspergillus oryzae genome database; http://aspor.cbrc.jp/). The information of array design used in this study is described in the Fermlab website.

RESULTS

Construction of chromosomal deletion strains by use of loop-out recombination (resolution-type recombination).

A loop-out deletion (resolution-type recombination) method, shown in Fig. 1B, was successfully applied to ku70-disrupted A. oryzae (RkuN16ptr1) and A. sojae (Askuptr8) strains to generate large chromosomal deletions. The method consists of four steps. Initially, a PCR-amplified fragment from a pyrG-mediated vector (pkvb-PG2) (Fig. 1A) was transformed to the recipient ku70-disrupted strains of A. oryzae and A. sojae (Fig. 1B, step 1). The amplified fragment consists of both pyrG and a sequence containing the right-hand region (moxY) of the deletion target (AF cluster) that has been flanked by sequences from the 3′ region of the pksA locus. Construction of a pyrG-mediated vector (pkvb-PG2) is schematically represented in Fig. 1A. A DNA sequence corresponding to the left-hand side of the deletion target (the 3′ region of pksA) was amplified by PCR and cloned by TA cloning. A pyrG fragment was then inserted into the cloned sequence (SmaI site), followed by insertion of the PCR fragment corresponding to the right-hand region (the 3′ region of moxY). Thus, the pyrG-mediated vector pkvb-PG2 consists of a sequence derived from the right-hand region (moxY) placed adjacent to the pyrG marker that has been inserted into the left-hand sequence (the 3′ region of the pksA locus) of the deletion target.

By using pyrG selection, we obtained a strain in which the moxY-pyrG marker was inserted into the left-hand region (the 3′ region of the pksA locus) by a replacement-type recombination (Fig. 1B, step 2). Thus, these pyrG transformants contain identical sequences (moxY) on both sides of the deletion target. In the next step, 5-FOA selection was used to select pyrG-negative strains (Fig. 1B, step 3). The bidirectional selection marker pyrG can be used for two-way selections: the presence of the pyrG marker is detected by a simple uridine-plus phenotype, and the absence of the pyrG marker is detected by a 5-FOA-resistant phenotype. A resolution-type homologous recombination between the identical sequences originally derived from the right-hand side of the deletion target results in the generation of a large deletion at the target region (the AF cluster) (Fig. 1B, step 4). This final step removes the pyrG marker, thereby allowing additional chromosomal deletions in the same strain.

Deletion of the AF biosynthetic gene cluster of the koji molds A. sojae and A. oryzae.

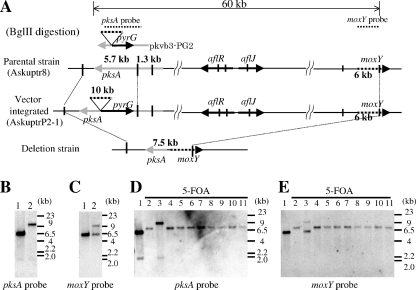

To delete the entire 60-kb region of the AF biosynthetic gene cluster from A. sojae by using the loop-out method (resolution-type recombination) (Fig. 2A), the A. sojae Δku70 strain (Askuptr8) was transformed with an 8-kb PCR amplification product from an entire AF cluster deletion vector (pkvb-PG2). The primer pair pkdelU-pkdelL was used in this process, and one of the transformants (AskuptrP2-1) was analyzed by Southern hybridization. As a result, 5.7-kb and 1.3-kb bands in the parental Δku70 strain (Askuptr8) that hybridized to a pksA probe (Fig. 2B, lane 1) were shifted to 10 kb and 1.3 kb in the transformant (AskuptrP2-1) (Fig. 2B, lane 2). Further, a single 6.0-kb band in the parental Δku70 strain (Askuptr8) that hybridized to the moxY probe (Fig. 2C, lane 1) was replaced by 6.0-kb and 10-kb bands in the AskuptrP2-1 strain (Fig. 2C, lane 2). Thus, the integration of the deletion vector in the pksA site of AskuptrP2-1 strain was confirmed. AskuptrP2-1 was used as a deletion host for the generation of the deletion strain in the following experiment.

FIG. 2.

Construction of A. sojae AF cluster deletion strains by use of the loop-out method. (A) Schematic representation of the restriction map of an AF cluster deletion strain. The parental A. sojae Δku70 strain (top), the strain in which the deletion vector was integrated at the pksA site (middle), and the strain from which the AF cluster was deleted by the loop-out method (bottom) are shown. (B and C) Southern hybridization analysis using the pksA probe (B) and the moxY probe (C). BglII-digested genomic DNA of the parental strain (lane 1) and the strain in which the deletion vector was integrated at the pksA site (lane 2) is shown. (D and E) Southern hybridization analysis of the AF cluster deletion strains by use of the pksA probe (D) and the moxY probe (E). BglII-digested genomic DNA of the parental strain (lane 1) and the 5-FOA-resistant strains (lanes 2 to 11) is shown.

To construct an entire AF deletion strain, the conidiospores of AskuptrP2-1 were spread on CZ plates containing 5-FOA, and 5-FOA-resistant colonies were selected. 5-FOA-resistant colonies were obtained at a frequency of approximately 2 colonies per 105 conidiospores (Table 3) of the AskuptrP2-1 strain. Ten 5-FOA-resistant colonies were selected, and Southern hybridization was carried out. In Fig. 2D, lane 1 shows the parental Δku70 strain, and lanes 2 to 11 show 5-FOA-resistant strains (AskuptrP2-1-F1 to AskuptrP2-1-F10). The BglII bands of 5.7 and 1.3 kb in the parental Δku70 strain that hybridized to the pksA probe (Fig. 2D, lane 1) were replaced with a 7.5-kb band in 9 of the 10 5-FOA-resistant strains (Fig. 2D, lane 2 and lanes 4 to 11). Further, a 6-kb BglII band in the parental Δku70 strain that hybridized to the moxY probe (Fig. 2E, lane 1) was shifted to a 7.5-kb band in the nine 5-FOA-resistant strains (Fig. 2E, lanes 2 and 4 to 11). These results indicated that the AF cluster was excised from these nine strains (AskuptrP2-1-F1 and AskuptrP2-1-F3 to AskuptrP2-1-F10). The band pattern of the remaining 5-FOA-resistant strain (AskuptrP2-1-F2) was the same as that of the deletion host strain (AskuptrP2-1) (Fig. 2B, lane 2). This suggested that the pyrG gene was inactivated in this strain, presumably by a point mutation. In short, the 60-kb region of the AF cluster deletion strains of A. sojae was constructed efficiently using this 5-FOA- and pyrG-mediated method.

TABLE 3.

Generation of large deletions in the telomere-neighboring region of the short arm of chromosome 3, including the AF gene cluster, by use of the A. sojae Δku70 strain

| Deletion length (kb) | 5-FOA frequencya | No. of strains

|

Efficiency (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-FOA resistant | Large deletion | |||

| 30 (first half) | (1.9 ± 0.8) × 10−4 | 12 | 12 | 100 |

| 30 (second half) | (3.9 ± 4.1) × 10−6 | 10 | 10 | 100 |

| 60 (entire AF) | (2.2 ± 0.8) × 10−5 | 10 | 9 | 90 |

| 100 | (2.4 ± 1.3) × 10−7 | 8 | 2 | 25 |

| 200 | (2.3 ± 1.4) × 10−7 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

Frequency of occurrence of 5-FOA-resistant strains (number of colonies on 5-FOA plates/total number of colonies spread). Numbers are the means ± standard deviations for triplicate experimental data.

Next, we constructed an AF cluster deletion strain of A. oryzae by using the loop-out method. A ku70-disrupted A. oryzae strain (RkuN16ptr1) was transformed with the PCR amplification product from the AF deletion vector pkvb-PG2 by using the primers pkdelU and pkdelL (Fig. 3A). We performed Southern hybridization and determined that a 2.4-kb band in the parental strain (RkuN16ptr1) that hybridized to pksA (Fig. 3B, lane 1) was shifted to a 10-kb band in the RkuptrP2-1 transformant (Fig. 3B, lane 2). Further, 6-kb and 8-kb bands in the parental strain (RkuN16ptr1) that hybridized to the moxY probe (Fig. 3C, lane 1) were replaced by 6-kb, 8-kb, and 10-kb bands in the RkuptrP2-1 transformant (Fig. 3C, lane 2). Thus, an RkuptrP2-1 strain with the deletion vector integrated at the pksA site was obtained. Conidiospores of RkuptrP2-1 were spread on 5-FOA plates. 5-FOA-resistant colonies were obtained at a frequency of approximately 4 colonies per 106 conidiospores (Table 4) of the RkuptrP2-1 strain. Nine of the 5-FOA-resistant colonies were selected for Southern hybridization analysis. A 10-kb band in the deletion host strain (RkuptrP2-1) that hybridized to the pksA probe (Fig. 3B, lane 2) was shifted to a 5.8-kb band in 5-FOA-resistant strains 2 and 6 to 9 (Fig. 3B, lanes 4 and 8 to 11). Further, 6-kb, 8-kb, and 10-kb bands in the deletion host strain that hybridized to the moxY probe (Fig. 3C, lane 2) were replaced by 5.8-kb and 8-kb bands in 5-FOA-resistant strains 2 and 6 to 9 (Fig. 3C, lanes 4 and 8 to 11). These results indicated that the AF biosynthetic gene cluster was deleted from these five 5-FOA-resistant strains (Fig. 3B and C, lanes 4 and 8 to 11) by precise loop-out recombination.

FIG. 3.

Construction of an AF gene cluster deletion A. oryzae strain (deletion of the entire 60-kb cluster). (A) BglII restriction map of the A. oryzae AF cluster and deletion construct. The parental A. oryzae Δku70 strain (top), the strain in which the deletion vector was integrated at the pksA site (middle), and the strain in which the AF cluster was deleted by the loop-out method (bottom) are shown. (B and C) Southern hybridization blots probed with pksA and moxY are shown. BglII-digested genomic DNA of the parental strain (lane 1), the strain in which the deletion vector was integrated at the pksA site (lane 2), and 5-FOA-resistant strains (lanes 3 to 11) are shown.

TABLE 4.

Generation of large deletions in the telomere-neighboring region of the short arm of chromosome 3, including the AF gene cluster, by use of the A. oryzae Δku70 strain

| Deletion length (kb) | 5-FOA frequencya | No. of strains

|

Efficiency (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-FOA resistant | Large deletion | |||

| 60 (entire AF) | (4.5 ± 0.8) × 10−6 | 8 | 5 | 63 |

| 100 | (8.4 ± 0.7) × 10−5 | 5 | 5 | 100 |

| 200 | (9.5 ± 1.5) × 10−6 | 5 | 5 | 100 |

Frequency of occurrence of 5-FOA-resistant strains (number of colonies on 5-FOA plates/total number of colonies spread). Numbers are the means ± standard deviations for triplicate experimental data.

5-FOA-resistant strain no. 2 was used for further analysis by comparative genome hybridization (CGH) (see Fig. 6). One strain, namely, no. 5 (Fig. 3, lane 7), exhibited the same hybridization pattern as the deletion host strain. The strains numbered 1, 3, and 4 exhibited illegitimate recombination patterns. In the case of 5-FOA-resistant strain no. 1, 5.8-kb and 8-kb bands were hybridized to the moxY probe, thereby suggesting precise recombination (Fig. 3C, lane 3). No band hybridized to the pks probe, indicating that the pksA gene was lost in 5-FOA-resistant strain no. 1 (Fig. 3B, lane 3). In 5-FOA-resistant strains 3 and 4, no band hybridized to the pks probe or the moxY probe (Fig. 3, lanes 5 and 6), indicating that both pksA and moxY were lost in these strains. These results suggested that the AF cluster of A. oryzae was successfully deleted from these strains, presumably by illegitimate recombination.

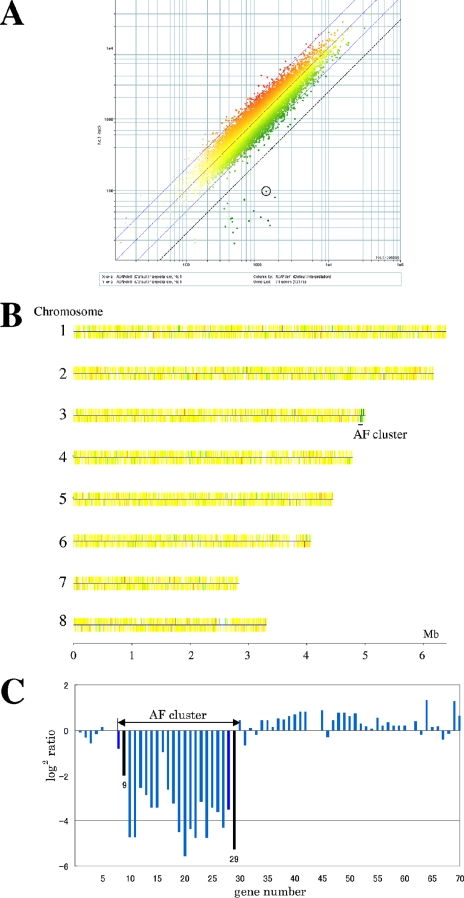

FIG. 6.

Microarray-based CGH of the strain with deletion of the AF cluster. (A) Scatter plot of the DNA microarray result. The three blue diagonal lines indicate ratios of the sample to the reference intensities of 2, 1, and 1/2 from left to right, respectively. The dotted line parallel to the blue lines indicates a ratio of 1/4. All the dots below the dotted line except the dot surrounded by the black circle correspond to the genes that were deleted in this work. (B) Chromosomal map of CGH. The CGH result was mapped onto the A. oryzae chromosomes. Red and green indicate that the log2 ratios of the sample to the reference intensities are higher and lower than 0, respectively. A black line under chromosome 3 indicates the location of the AF cluster. (C) Histogram of CGH in the AF cluster region. The y axis designates the log2 ratios of probes in the subtelomeric region of the right arm of chromosome 3, where the AF cluster locates. Each bar represents the intensity of a probe corresponding to each gene in this region. The labels in the x axis, 1 to 70, correspond to gene numbers AO090026000001 to AO090026000070. The two black bars in the figure indicate the data corresponding to the probes of pksA (AO090026000009) and cypX (AO090026000029).

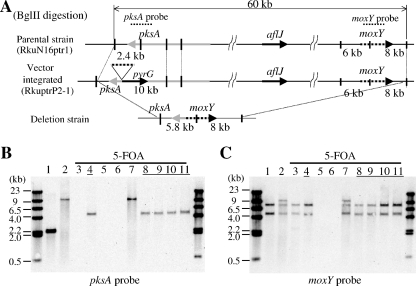

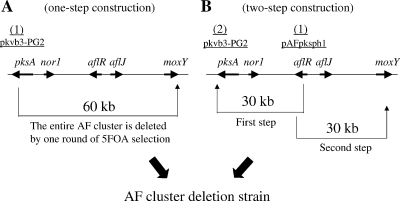

Construction of AF cluster deletion by multiple deletion steps.

To confirm the possibility of generation of multiple deletions by pyrG marker recycling, the entire AF cluster was deleted by two rounds of deletion (Fig. 4B) and the result compared with that of one round of deletion (Fig. 4A). Initially, deletion of the first half of the AF biosynthetic gene cluster (30 kb) was performed, followed by deletion of the second half (30 kb) from the A. sojae Δku70 strain.

FIG. 4.

Construction of AF gene cluster deletion strains in multiple steps by use of the A. sojae Δku70 strain. The number on the gene map (top) indicates the position of the loop-out-type vector integrated. (A) Construction of an AF cluster deletion strain in one step. The vector was integrated in the pksA site, and 60 kb of the AF cluster was deleted by 5-FOA-mediated loop-out recombination between the vector and moxY. (B) Construction of an AF cluster deletion strain in two rounds of operation. In the first step, the vector was integrated in the aflR site. The first half of the AF cluster was deleted through loop-out recombination between the vector and pksA. In the second step, the vector was integrated at the pksA site of the first-half-deleted strain. The remaining, second half of the AF cluster was deleted in the second step by loop-out recombination between the vector and moxY.

The vector for the first half of the AF cluster (pAFpksph1), amplified using the primers AF-U and AF-L, was integrated into the aflR site of the A. sojae ku70 strain (Askuptr8) (26). This resulted in the integration of pyrG and a 1.8-kb part of the pksA fragment into the aflR site of the transformant. The conidiospores of the resultant AFpksph6 transformant were spread on 5-FOA plates. 5-FOA-resistant colonies were obtained at a frequency of approximately 2 colonies per 104 conidiospores (Table 3). Ten 5-FOA-resistant strains were selected, and Southern hybridization analysis was performed using the pksA and moxY probes. The analysis revealed that the first half of the AF cluster was deleted in all 10 5-FOA-resistant strains (AFpksph6D1-10).

To measure the deletion efficiency of the second half of the AF cluster, a deletion vector for AFs, namely, pkvb-PG2, was integrated into the pksA site of the first half of the AF cluster deletion strain (AFpksph6D1). Vector integration in the pksA site in the transformant AFpksph6D-P2-8-1 was confirmed. The conidiospores of the AFpksph6D-P2-8-1 strain were spread on 5-FOA plates. Ten 5-FOA-resistant strains were obtained, and hybridizations were performed using the pksA and moxY probes. The AF cluster was found to be deleted in all 10 5-FOA-resistant strains. The frequency of appearance of the 5-FOA-resistant colonies was higher in the deletion of the first half (1.9 × 10−4) than in the deletion of the entire AF cluster (2.2 × 10−5) and lowest in the deletion of the second half (3.9 × 10−6) (Table 3). These results indicated that pyrG marker recycling is feasible in the generation of chromosomal deletions.

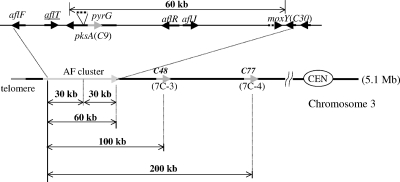

Construction of strains with extensive deletion in chromosome 3.

To determine the limit of the deletion range for the 5-FOA-mediated loop-out method, we focused on chromosome 3, which contains the AF cluster of the koji strains. The vectors for 100-kb deletion (p7C-3) and 200-kb deletion (p7C-4) were transformed into the A. sojae Δku70 strain (Askuptr8) and the A. oryzae Δku70 strain (RkuN16ptr1) (Fig. 5). Transformants containing the deletion vectors in the pksA site were selected, and conidiospores of the transformants were spread on 5-FOA plates. Colonies resistant to 5-FOA were obtained, with a frequency of approximately 8.4 colonies per 105 conidiospores from the p7C-3 transformant and 9.5 colonies per 106 conidiospores from the p7C-4 transformant of A. oryzae (Table 4). The 5-FOA-resistant strains were analyzed by Southern hybridization using the pksA, C48, C77, and moxY probes. Analysis revealed that both 100-kb and 200-kb deletions were achieved in all five 5-FOA-resistant colonies of A. oryzae (Table 4). In the case of A. sojae, 100-kb deletion strains were obtained from two of the four 5-FOA-resistant colonies (Table 3). However, no 200-kb deletion was obtained from the 5-FOA-resistant colonies of A. sojae (Table 3). Thus, deletions of 200 kb and up to 100 kb were achieved in chromosome 3 of A. oryzae and A. sojae, respectively.

FIG. 5.

Schematic representation of the extensive chromosomal deletions of chromosome 3. Chromosomal region of deletion construction in the short arm of chromosome 3, including the AF biosynthetic cluster. CEN, centromere.

Effect of ku70 deficiency on the frequency of loop-out-type deletion.

We investigated the effect of ku70 deficiency on the frequency of loop-out-type deletion. The ku70+ strain of A. sojae was used to construct a strain that had the deletion vector for the AF cluster in the pksA site. One strain with the deletion vector in the pksA site, designated Asvb19, was obtained from 62 transformants of the I-6 strain (ku70+ A. sojae strain). This relatively low targeting frequency was likely related to the presence of a functional ku70 gene. The conidiospores of the Asvb19 strain were spread on 5-FOA plates to determine the frequencies of appearance of 5-FOA-resistant colonies. Genomic DNA was extracted from the 5-FOA-resistant strains, and the efficiency of AF deletion was investigated. The frequency of 5-FOA-resistant colonies obtained from the Asvb19 strain was approximately 2.7 × 10−6, in contrast to 2.2 × 10−5 for the ku70-deficient strain (Table 5). These results suggest that the frequency of 5-FOA resistance in the ku70-deficient strain was approximately 1 order of magnitude greater than the corresponding frequency in the wild-type strain that we examined.

TABLE 5.

Effect of ku70 deficiency on generation of large deletion strains by use of loop-out deletion vectors

| A. sojae genotype | 5-FOA frequencya | Ratiob | Efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Δku70 | (2.2 ± 0.8) × 10−5 | 9/10 | 90 |

| ku70+ | (2.7 ± 1.7) × 10−6 | 9/8 | 89 |

Frequency of occurrence of 5-FOA-resistant strains. Numbers are the means ± standard deviations for triplicate experimental data.

The number of AF cluster deletion strains versus the total number of 5-FOA-resistant strains.

Next, deletions of the AF cluster in the 5-FOA-resistant colonies were confirmed by Southern hybridization. As summarized in Table 4, 89% (8 of 9) of the 5-FOA-resistant colonies from the wild-type strain and 90% (9 of 10) of the 5-FOA colonies from the ku70-deficient strain lost the AF cluster. This indicated that the deletion of the AF cluster by homologous recombination occurred in almost all the 5-FOA-resistant colonies and that the ratio of deletion was the same between the ku70-deficient strain and the wild-type strain.

Comparative genomic hybridization.

To confirm the absence of a large, unintended chromosomal deletion(s) or amplification of particular loci during transformation and successive 5-FOA selection, we performed CGH experiments. Figure 6 clearly indicates the deletion of the region from pksA (AO090026000009) to cypX (AO090026000029) of the A. oryzae 5-FOA-resistant no. 2 strain. All 21 probes in this region showed log2 values below −2, except the probe AO090026000016, located adjacent to aflJ (log2 value = −0.98) (Fig. 6C). In contrast, only a single probe (AO090011000868) other than the probes mentioned above showed a log2 value below −2. Only approximately 1% of probes (108, or 97 with AOX excluded) among all 12,116 (11,354 with AOX excluded) probes showed log2 values between −2 and −1. However, none showed a contiguous cluster consisting of more than two probes. On the other hand, two probes showed log2 values greater than 2, and 121 (111 with AOX excluded) probes showed values between 1 and 2. The probes of the latter value range formed only two small clusters (one with AO090103000295 and AO090103000296 and one with AO090311000001, AO090311000002, and AO090311000003). These values suggest that possible deletion or amplification could be within the error range of the DNA microarray experiments because the value only slightly exceeded the range of significant difference. Further, the unintended modification, if any, is limited in a few loci and over a narrow range. Moreover, the results of Southern hybridization using the probes corresponding to the relevant regions (AO090011000868, AO090103000295, and AO090311000001) showed that there is no difference in band pattern between the deletion strain and the wild-type strain (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

To date, the generation of large chromosomal deletions in koji molds by genetic engineering has been difficult and laborious because of the low frequency of homologous recombination (27). In fact, there are only few reports on the construction of large chromosomal deletion by targeted homologous recombination in filamentous fungi. In Aspergillus nidulans, only one strain with a 38-kb chromosomal deletion was obtained from 64 transformants by replacement-type recombination (2). In contrast, the present study showed that primary targeting vector integration was easily achieved by using ku70-deficient koji mold strains and that at least a 200-kb deletion can be obtained efficiently by performing 5-FOA selection. Moreover, no additional sequence, including the marker gene, remained in the deletion strains, and the resultant strains can be directly used for the next cycle of deletion.

It has been reported that protoplast-based genetic transformation might cause karyotypic alterations, including apparent chromosome loss, massive size alterations, and the appearance of large chromosomes (31). In our study, the results of the CGH experiments indicate that our present technique did not cause such unintended chromosomal modifications for the deletion of the AF cluster.

The transformants obtained using the loop-out method, in combination with a ku70-deficient strain and pyrG-mediated 5-FOA selection, have large chromosomal deletions that are efficiently produced. With a few exceptions, the frequencies at which 5-FOA-resistant colonies occurred were essentially proportional to the length of the region deleted (Tables 3 and 4). The frequencies of 5-FOA resistance associated with deletions of 100 kb and 200 kb gradually decreased as the length of deletion increased in A. oryzae, with the exception of the 60-kb deletion (Table 4). Moreover, the frequencies of 5-FOA resistance associated with the deletions of 30 kb, 60 kb, and 100 kb gradually decreased with increases in the lengths of deletion in A. sojae (Table 3). With the deletion of the second half of the AF cluster, the frequency of 5-FOA resistance was decreased, despite the fact that the deleted region was relatively small (Fig. 5). The vectors and the integration site were the same in the two strains, the only difference being the length of the deleted area. The frequency of 5-FOA resistance associated with the deletion of the second half of the AF gene cluster was 2 orders of magnitude lower than the frequency associated with the deletion of the first half (Table 3). Although these frequencies differed, the targeted regions were similar in length. These observations suggest that the frequency of large deletion by intrachromosomal homologous recombination was not simply length dependent. Loop-out recombination could be affected by the relative positions of two homologous regions.

In the case of deletion in the short arm of chromosome 3 in the A. sojae strain, the 200-kb deletion was difficult to obtain using the loop-out method (Table 3 and Fig. 5). However, we have achieved deletion of the same 200-kb region in A. sojae strain by using an alternative method (replacement-type recombination) (T. Takahashi, F.-J. Jin, and Y. Koyama, submitted for publication); this indicates that the genes included in the 200-kb region of chromosome 3 of A. sojae were not essential for cell survival. These results suggest that loop-out recombination, i.e., intrachromosomal recombination, is sensitive to the effect of genome structure. In addition, the vectors used in the 100- and 200-kb deletions were constructed using A. oryzae sequence. Although the sequence identity between A. sojae and A. oryzae in the relevant region was high enough to facilitate homologous recombination, it may affect the decrease of recombination frequency in the A. sojae strain. The details of the mechanism of this phenomenon remain unclear and require further investigation. However, this mechanism may depend on the accessibility of the recombination arm of the deletion vector to the homologous DNA region.

Some of the 5-FOA-resistant colonies obtained from the A. oryzae strain in the construction of the 60-kb deletion of chromosome 3 by use of the loop-out method have illegitimate deletion, i.e., extensive deletion (Fig. 3). However, in the cases of the 100-kb and 200-kb deletions of chromosome 3, all the 5-FOA-resistant colonies had chromosomal deletions resulting from precise homologous recombination (Table 4). Furthermore, in the cases of the 100-kb and 200-kb deletions in chromosome 4 of A. oryzae, most of the 5-FOA-resistant colonies also had precise deletions (unpublished data). On the other hand, in A. sojae, all the deletions of 60-kb and 100-kb regions of the AF cluster were achieved by precise homologous recombination, and illegitimate deletion was not observed (Fig. 2 and Table 3). These results indicated that the 5-FOA-mediated loop-out method functioned accurately not only in A. sojae but also in the Δku70 strain of A. oryzae. Thus, the illegitimate deletion in the Δku70 strain is not attributable to the 5-FOA selection procedure. Presumably, deletions may be affected by the instability of the telomeric ends of chromosomes. The AF gene cluster of A. oryzae is located in a region only 25 kb from the telomeric end of chromosome 3 (Fig. 5), although that of A. sojae has not been determined. Consequently, the exact reason for the partial deletion remains unclear. To clarify this, determination of the precise size of deletion and sequencing of the deletion borders are necessary.

The strains constructed in the present study by deleting a 200-kb region of chromosome 3 lost at least 67 open reading frames. However, the deletion strains exhibited only slight growth delay and no obvious phenotypic change compared with the parental strains. This suggests that the genes located in this telomere-neighboring region—the 200-kb region of the short arm end of chromosome 3—do not play an important role in cell viability. These results are consistent with the observation that genes in the AF cluster were not transcribed in A. sojae and A. oryzae (6, 28). It has been reported that disruption of genes located on the telomere side of the border of the AF cluster, namely, norB, cypA, and aflT, have little effect on AF production in A. parasiticus (4, 9). Therefore, we aimed to delete the AF biosynthetic gene cluster between the coding region of the pksA gene and that of the cypX gene. As a result of this deletion, a region spanning most of the pksA gene to the cypX gene was excised from chromosome 3. The function of the pksA gene was lost since the deletion contained more than two-thirds of the coding region of the gene, including the promoter. Consequently, the genes related to early steps in the biosynthesis of AFs—pksA, encoding polyketide synthase, and fas-1 and fas-2, encoding fatty acid synthase—were deleted. The genes related to the activation and regulation of the AF gene cluster, aflR and aflJ, were also deleted from chromosome 3. Deletion of the aflR, pksA, or fas gene in A. parasiticus and A. flavus results in no production of AF and its intermediates, due to inhibition of AF biosynthesis (3, 5, 18). The cypX and moxY genes are located on the other side of the border of the AF cluster. Both of these genes encode monooxygenase and participate in only a single intermediate conversion step (30). On the basis of the aforementioned reasons, we conclude that the AF biosynthetic gene cluster-deleted strains generated in this study completely lost genes known to be essential for AF biosynthesis in other aspergilli.

The procedure established in this study enables us to efficiently generate large-deletion mutants of the koji molds. This technique may also be applicable to other filamentous fungi since increased gene targeting for ku disruption has been widely reported (14, 15, 19, 20, 21, 23). This technique enables the excision of regions that are either dispensable for viability or desirable to remove from the perspective of enhancing food safety. This procedure is also applicable to industrial filamentous fungal species such as Aspergillus niger, the complete genome sequence of which was recently determined (22). Removal of the genes related to the production of unnecessary metabolites may result in growth enhancement by virtue of reduction in energy consumption by the cell. If such a phenotype is obtained from the relevant strains, it will contribute to the improvement of industrial production.

In conclusion, we successfully constructed chromosomal deletion mutants of the koji molds with high efficiency by using a ku70 disruption strain in combination with a bidirectional pyrG marker. In addition, we confirmed that pyrG marker recycling is feasible in the generation of chromosomal deletions. Therefore, large chromosomal deletions can repeatedly be generated within the chromosomes of the koji molds. Moreover, no additional sequence in the vector, including the marker gene, remained in the resulting deletion strains; this feature will be suitable for breeding food-grade organisms. Using this technique, we have successfully constructed AF cluster-deleted A. oryzae and A. sojae strains. Although the koji mold strains have not produced AF under any condition, this will permanently remove the concerns about AF production by the relevant strains. Further, the ku70 mutation in the deletion strains can easily be restored by cotransformation of wild-type ku70 and pyrG fragments. Deletion of various regions in the chromosomes of the koji molds may be useful in the functional analysis of gene clusters related to various cellular processes, including secondary metabolite production.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Noriko Yamane and Tomomi Toda for supporting the CGH experiment. We thank Genryo Umitsuki for helpful discussion and Yukio Senou for his technical assistance. We also thank Hideo Takahashi for reading the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Program for the Promotion of Basic Research Activities for Innovative Biosciences of the Bio-Oriented Technology Research Advancement Institution.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 24 October 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abremski, K., A. Wiezbicki, B. Frommer, and R. H. Hoess. 1986. Bacteriophage P1 Cre-loxP site-specific recombination. Site-specific DNA topoisomerase activity of the Cre recombination protein. J. Biol. Chem. 261:391-396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aramayo, R., T. H. Adams, and W. E. Timberlake. 1989. A large cluster of highly expressed gene is dispensable for growth and development in Aspergillus nidulans. Genetics 122:65-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cary, J. W., K. C. Ehrlich, M. Wright, P.-K. Chang, and D. Bhatnagar. 2000. Generation of aflR disruption mutants of Aspergillus parasiticus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 53:680-684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang, P.-K., J. Yu, and J.-H. Yu. 2004. aflT, a MFS transporter-encoding gene located in the aflatoxin gene cluster, does not have a significant role in aflatoxin secretion. Fungal Genet. Biol. 41:911-920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang, P.-K., J. W. Cary, J. Yu, D. Bhatnagar, and T. E. Cleveland. 1995. The Aspergillus parasiticus polyketide synthase gene pksA, a homolog of Aspergillus nidulans wA, is required for aflatoxin B1 biosynthesis. Mol. Gen. Genet. 248:270-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang, P.-K., K. Matsushima, T. Takahashi, J. Yu, K. Abe, D. Bhatnagar, G.-F. Yuan, Y. Koyama, and T. E. Cleveland. 2007. Understanding nonaflatoxigenicity of Aspergillus sojae: a windfall of aflatoxin biosynthesis research. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 76:977-984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Critchlow, S. E., and S. P. Jackson. 1998. DNA end-joining: from yeast to man. Trends Biochem. Sci. 23:394-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.d'Enfert, C. 1996. Selection of multiple disruption events in Aspergillus fumigatus using the orotidine-5′-decarboxylase gene, pyrG, as a unique transformation marker. Curr. Genet. 30:76-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ehrlich, K. C., P.-K. Chang, J. Yu, and P. J. Cotty. 2004. Aflatoxin biosynthesis cluster gene cypA is required for G aflatoxin formation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:6518-6524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gu, H., Y. R. Zou, and K. Rajewsky. 1993. Independent control of immunoglobulin switch recombination at individual switch regions evidenced through Cre-loxP-mediated gene targeting. Cell 73:1155-1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirashima, K., T. Iwaki, K. Takegawa, Y. Giga-Hama, and H. Tohda. 2006. A simple and effective chromosome modification method for large-scale deletion of genome sequences and identification of essential genes in fission yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jinks-Robertson, S., M. Micheltch, and S. Ramcharan. 1993. Substrate length requirements for efficient mitotic recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:3937-3950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klein, H. L. 1988. Different types of recombination events are controlled by the RAD1 and RAD52 genes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 120:367-377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kooistra, R., P. J. Hooykaas, and H. Y. Steensma. 2004. Efficient gene targeting in Kluyveromyces lactis. Yeast 21:781-792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krappmann, S., C. Sasse, and G. H. Braus. 2006. Gene targeting in Aspergillus fumigatus by homologous recombination is facilitated in a nonhomologous end-joining-deficient genetic background. Eukaryot. Cell 5:212-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loonstra, A., M. Vooijs, H. B. Beverloo, B. A. Allak, E. van Drunen, R. Kanaar, A. Berns, and J. Jonkers. 2001. Growth inhibition and DNA damage induced by Cre recombinase in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:9209-9214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Machida, M., K. Asai, M. Sano, T. Tanaka, T. Kumagai, G. Terai, K.-I. Kusumoto, T. Arima, O. Akita, Y. Kashiwagi, K. Abe, K. Gomi, H. Horiuchi, K. Kitamoto, T. Kobayashi, M. Takeuchi, D. W. Denning, G. E. Galagan, W. C. Nierman, J. Yu, D. B. Archer, J. W. Bennett, D. Bhatnagar, T. E. Cleveland, N. D. Fedrova, O. Gotoh, H. Horikawa, A. Hosoyama, M. Ichinomiya, R. Igarashi, K. Iwashita, P. R. Juvvadi, M. Kato, Y. Kato, T. Kin, A. Kokubun, H. Maeda, N. Maeyama, J.-I. Maruyama, H. Nagasaki, T. Nakajima, K. Oda, K. Okada, I. Paulsen, K. Sakamoto, T. Sawano, M. Takahashi, K. Takase, Y. Terabayashi, J. R. Wortman, O. Yamada, Y. Yamagata, H. Anazawa, Y. Hata, Y. Koide, T. Komori, Y. Koyama, T. Minetoki, S. Suharnan, A. Tanaka, K. Isono, S. Kuhara, N. Ogasawara, and H. Kikuchi. 2005. Genome sequencing and analysis of Aspergillus oryzae. Nature 438:1157-1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahanti, N., D. Bhatnagar, J. W. Cary, J. Joubran, and J. E. Linz. 1996. Structure and function of fas-1A, a gene encoding a putative fatty acid synthetase directly involved in aflatoxin biosynthesis in Aspergillus parasiticus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:191-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyer, V., M. Arentshorst, A. El-Ghezal, A. C. Drews, R. Kooistra, C. A. van den Hondel, and A. F. Ram. 2007. Highly efficient gene targeting in the Aspergillus niger kusA mutant. J. Biotechnol. 128:770-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nayak, T., E. Szewczyk, C. E. Oakley, A. Osmani, L. Uki, S. L. Murray, M. J. Hynes, S. A. Osmani, and B. R. Oakley. 2006. A versatile and efficient gene-targeting system for Aspergillus nidulans. Genetics 172:1557-1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ninomiya, Y., K. Suzuki, C. Ishii, and H. Inoue. 2004. Highly efficient gene replacements in Neurospora strains deficient for nonhomologous end-joining. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:12248-12253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pel, H. J., J. H. de Winde, D. B. Archer, P. S. Dyer, G. Hofmann, P. J. Schaap, G. Turner, R. P. de Vries, R. Albang, K. Albermann, M. R. Andersen, J. D. Bendtsen, J. A. Benen, M. van den Berg, S. Breestraat, M. X. Caddick, R. Contreras, M. Cornell, P. M. Coutinho, E. G. Danchin, A. J. Debets, P. Dekker, P. W. van Dijck, A. van Dijk, L. Dijkhuizen, A. J. Driessen, C. d'Enfert, S. Geysens, C. Goosen, G. S. Groot, P. W. de Groot, T. Guillemette, B. Henrissat, M. Herweijer, J. P. van den Hombergh, C. A. van den Hondel, R. T. van der Heijden, R. M. van der Kaaij, F. M. Klis, H. J. Kools, C. P. Kubicek, P. A. van Kuyk, J. Lauber, X. Lu, M. J. van der Maarel, R. Meulenberg, H. Menke, M. A. Mortimer, J. Nielsen, S. G. Oliver, M. Olsthoorn, K. Pal, N. N. van Peij, A. F. Ram, U. Rinas, J. A. Roubos, C. M. Sagt, M. Schmoll, J. Sun, D. Ussery, J. Varga, W. Vervecken, P. J. van de Vondervoort, H. Wedler, H. A. Wosten, A. P. Zeng, A. J. van Ooyen, J. Visser, J., and H. Stam. 2007. Genome sequencing and analysis of the versatile cell factory Aspergillus niger CBS513.88. Nat. Biotechnol. 25:221-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poggeler, S., and U. Kuck. 2006. Highly efficient generation of signal transduction knockout mutants using a fungal strain deficient in the mammalian ku70 ortholog. Gene 378:1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sauer, B. 1987. Functional expression of the cre-lox site-specific recombination system in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7:2087-2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sieburth, L. E., G. N. Drews, and E. M. Meyerowitz. 1998. Non-autonomy of AGAMOUS function in flower development: use of a Cre/loxP method for mosaic analysis in Arabidopsis. Development 125:4303-4312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takahashi, T., T. Masuda, and Y. Koyama. 2006. Enhanced gene targeting frequency in ku70 and ku80 disruption mutants of Aspergillus sojae and Aspergillus oryzae. Mol. Genet. Genomics 275:460-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takahashi, T., O. Hatamoto, Y. Koyama, and K. Abe. 2004. Efficient gene disruption in the koji-mold Aspergillus sojae using a novel variation of the positive-negative method. Mol. Genet. Genomics 272:344-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tominaga, M., Y. H. Lee, R. Hayashi, Y. Suzuki, O. Yamada, K. Sakamoto, K. Gotoh, and O. Akita. 2006. Molecular analysis of an inactive aflatoxin biosynthesis gene cluster in Aspergillus oryzae RIB strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:484-490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Watson, A. J., L. J. Fuller, D. J. Jeens, and D. B. Archer. 1999. Homologs of aflatoxin biosynthesis genes and sequence of aflR in Aspergillus oryzae and Aspergillus sojae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:307-310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wen, Y., H. Hatabayashi, H. Arai, H. K. Kitamoto, and K. Yabe. 2005. Function of the cypX and moxY genes in aflatoxin biosynthesis in Aspergillus parasiticus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:3192-3198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xuei, X., and P. L. Skatrud. 1994. Molecular karyotype alterations induced by transformation in Aspergillus nidulans are mitotically stable. Curr. Genet. 26:225-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]