Abstract

Campylobacter jejuni is the most common cause of bacterial gastroenteritis in Luxembourg, with a marked seasonal peak during summer. The majority of these infections are thought to be sporadic, and the relative contribution of potential sources and reservoirs is still poorly understood. We monitored human cases from June to September 2006 (n = 124) by molecular characterization of isolates with the aim of rapidly detecting temporally related cases. In addition, isolates from poultry meat (n = 36) and cattle cecal contents (n = 48) were genotyped for comparison and identification of common clusters between veterinary and human C. jejuni populations. A total of 208 isolates were typed by sequencing the fla short variable region, macrorestriction analysis resolved by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), and multilocus sequence typing (MLST). We observed a high diversity of human strains during a given summer season. Poultry and human isolates had a higher diversity of sequence types than isolates of bovine origin, for which clonal complexes CC21 (41.6%) and CC61 (18.7%) were predominant. CC21 was also the most common complex found among human isolates (21.8%). The substantial concordance between PFGE and MLST results for this last group of strains suggests that they are clonally related. Our study indicates that while poultry remains an important source, cattle could be an underestimated reservoir of human C. jejuni cases. Transmission mechanisms of cattle-specific strains warrant further investigation.

Campylobacter spp. have emerged as the leading causes of bacterial gastroenteritis in industrialized countries over the last 30 years (34, 45, 46). Among species isolated from human diarrheal disease, C. jejuni is predominant and usually represents 80 to 90% of all reported campylobacteriosis (14, 32). In Luxembourg, the incidence has been increasing in recent years, with 300 to 400 cases reported per year between 2004 and 2006. Besides the self-limiting clinical manifestations of campylobacteriosis, mainly characterized by an acute gastrointestinal illness, Guillain-Barré syndrome has been identified as a serious but rare postinfection complication (32).

C. jejuni forms part of the normal gut microflora of a variety of wild and domestic animals including cattle, sheep, birds, and pets. It is considered to be fragile and sensitive to environmental stress, with a limited tolerance to oxygen, drying, and heating (24, 33). Despite this apparent vulnerability, its survival and transmission by the fecal-oral route seem to be effective, as the increasing prevalence in many countries shows. Poultry meat is considered to be the main vector of C. jejuni infection, and transmission is thought to occur either as a result of cross-contamination due to improper handling of raw meat or consumption of undercooked food (3, 48). Compared to the other major food-borne bacteria, Salmonella, few outbreaks are reported, and most cases of campylobacteriosis are considered to be “sporadic,” with a seasonal peak during summer (2). Few sources have been identified, and the role of reservoirs needs to be further investigated in order to better understand their relative contribution to human campylobacteriosis.

With the development of high-resolution molecular typing systems (1, 10, 16), efficient tools were applied to epidemiological studies. These genotypic methods have shown that Campylobacter spp. have a high genomic diversity which may reflect rapid adaptive changes during infection or colonization cycles (51). Mechanisms driving the generation of novel variants include natural transformation (50, 52), intra- and intergenomic recombination (23, 43), genomic rearrangements (35, 51), and chromosomal point mutations (49). Because of this genome plasticity, Campylobacter spp. display a weakly clonal population structure, in which the different lineages and the relatedness between isolates cannot be easily determined, particularly within the framework of long-term epidemiological studies. Based on a concept similar to multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, multilocus sequence typing (MLST) exploits the relative conservation in sequence of some genes in which variations are more likely to be selectively neutral because of their housekeeping functions (27). The typing scheme is based on the analysis of seven independent loci, and allelic diversity is mainly generated by homologous recombination. This approach was successfully developed to study Campylobacter populations (9) and is now recognized as the gold standard typing method for this bacteria genus.

The purpose of our study was to investigate the genetic diversity of the C. jejuni population isolated in Luxembourg and identify clusters common to human cases, retail poultry meat, and cattle cecal samples obtained at abattoirs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Campylobacter isolates.

Three sets of C. jejuni isolates collected in Luxembourg were included in the current study: 124 (59.6%) isolates from human infections, 48 (23.1%) isolates of bovine origin, and 36 (17.3%) isolates from poultry. The human isolates represent cases reported to the National Health Laboratory from June to September 2006, and 75% of this collection was received from hospitals and diagnostic laboratories in Luxembourg. Animal samples were all examined by the enrichment method using Preston broth (nutrient broth N.2 CM067B supplemented with growth supplement SR0232E, selective supplement SR117E, and 5% of laked horse blood SR048C; Oxoid, Drongen, Belgium). Isolates from cattle were collected from cecal contents at abattoirs from November 2005 to October 2006 and originated from 35 different farms. Initially, a smaller pilot study on cecal samples from cattle was conducted to determine the potential of two plating media: mCCDA (Campylobacter blood-free selective agar CM0739 plus selective supplement SR0155; Oxoid, Drongen, Belgium) and Campylosel (product 43253; BioMerieux, Marcy-l'Etoile, France) for recovering different strains characterized by combined fla typing and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). From 39 samples positive by both mCCDA and Campylosel analysis, identical strains were recovered with one exception; i.e., isolates had the same combined short variable region (SVR)-PFGE profile, but for one sample the two media yielded isolates with different combined SVR-PFGE profiles.

Poultry isolates were collected from raw retail meat including chicken (n = 31), turkey (n = 2), and duck (n = 2). The collection reflects the meat offered from different companies available in different supermarkets in Luxembourg. In addition, one strain of C. jejuni was isolated from chicken feces at a poultry laying farm in Luxembourg. All poultry samples were taken between October 2005 and February 2007, and the isolation procedure was performed only on mCCDA medium as a result of a pilot study on cattle samples. Species identification was determined by a PCR method (7) with the following modification: only primers targeting the mapA and ceuE genes of C. jejuni and Campylobacter coli, respectively, were used in duplex. Further information on the whole collection of isolates is listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Results of subtyping of all 208 isolates by MLST, FlaA SVR, and PFGE

| CC | ST no. | FlaA SVR nucleotide allelea | PFGE complex(es)b | No. of isolates from:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human stool | Poultry meat | Cattle cecum | ||||

| CC21 | 19 | 22-32-36-245 | 1-3-44 | 6 | 1 | 8 |

| 21 | 32-42-78-121-546-245 | 1-2-3-18-59 | 6 | 1 | 5 | |

| 44 | 78 | 30 | 1 | |||

| 50 | 36-265 | 2-3-6-8 | 6 | 1 | ||

| 53 | 32-52-138 | 3-8-65 | 3 | 1 | ||

| 262 | 37 | 3 | 5 | |||

| 760 | 36 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1728 | 8-36-105 | 3 | 3 | |||

| 2135 | 105 | 3 | 1 | |||

| CC22 | 22 | 161-232 | 64 | 1 | 1 | |

| CC42 | 42 | 274-440 | 16-22-52 | 2 | 4 | |

| CC45 | 45 | 2-5-8-15 | 20 | 5 | 1 | 3 |

| 168 | 36 | 20 | 1 | |||

| 233 | 2 | 20 | 1 | |||

| 334 | 239 | RF | 1 | |||

| 418 | 2 | 20 | 1 | |||

| 583 | 9-239-274 | RF | 3 | |||

| 1701 | 2 | 20 | 1 | |||

| CC48 | 38 | 41 | 32 | 1 | ||

| 48 | 32-36 | 9-37 | 4 | 2 | 3 | |

| 475 | 105 | 37-ND | 2 | |||

| 2889 | 32 | 9 | 1 | |||

| CC49 | 49 | 11 | 47 | 1 | ||

| CC52 | 775 | 57 | 49 | 1 | ||

| 2886 | 57 | 3 | 1 | |||

| CC61 | 61 | 21-42-232-1017 | 11 | 1 | 3 | |

| 81 | 42 | 11 | 1 | |||

| 352 | 4-42-44 | 11 | 1 | 2 | ||

| 432 | 37 | 11 | 1 | |||

| 2771 | 37 | 11 | 1 | |||

| 2891 | 36 | 11 | 1 | |||

| CC206 | 46 | 14-105 | 7-27-55 | 3 | ||

| 122 | 49-533 | 25-35 | 4 | 1 | ||

| 290 | 14 | 25 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 572 | 14-239-260-NF | 9-15-33-ND | 7 | |||

| 2104 | 9-245 | 9-33 | 2 | |||

| CC257 | 257 | 16 | 24 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| 824 | 34-278 | 5-51 | 6 | 2 | ||

| CC283 | 267 | 239 | RF | 1 | ||

| CC353 | 5 | 14 | 4 | 2 | ||

| 353 | 278 | 12 | 1 | |||

| 400 | 67 | 42-43 | 5 | 1 | ||

| 2641 | 14 | 13 | 2 | |||

| 2882 | 14 | 17 | 1 | |||

| CC354 | 354 | 18 | 31-34-56-63 | 4 | 2 | |

| 1073 | 208 | 46 | 1 | |||

| 2885 | 208 | 34 | 1 | |||

| 2888 | 34 | 5 | 1 | |||

| CC403 | 403 | 51-NF | 10-39 | 3 | ||

| CC433 | 2887 | 37 | 19 | 1 | ||

| CC443 | 51 | 21-32-196 | 26-27-57 | 4 | 2 | |

| 2034 | 16 | 60 | 1 | |||

| CC446 | 446 | NF | 54 | 1 | ||

| 450 | 34 | 45 | 1 | |||

| 978 | 34 | 53 | 1 | |||

| CC574 | 305 | 57 | 31 | 1 | 1 | |

| CC607 | 607 | 14 | 29-46 | 1 | 1 | |

| 863 | 255 | 29 | 1 | |||

| 904 | 222 | 29 | 1 | |||

| 1707 | 14-57 | 62-ND | 1 | 1 | ||

| CC658 | 523 | 317 | 50 | 1 | ||

| 658 | 5 | 36 | 1 | |||

| CC692 | 991 | 571 | 38 | 1 | ||

| CC1034 | 1956 | 264 | 40 | 1 | ||

| 2314 | 639 | 58 | 1 | |||

| UAc | 2884 | 14 | 13 | 1 | ||

| UA | 350 | 232 | 56 | 1 | ||

| UA | 464 | 260 | 23 | 1 | 3 | |

| UA | 586 | 433 | 61 | 2 | ||

| UA | 879 | 34-121 | 28-21 | 1 | 3 | |

| UA | 1409 | NF | 48 | 1 | ||

| UA | 1759 | 49 | 14 | 1 | ||

| UA | 2065 | 14 | 13 | 1 | ||

| UA | 2258 | 208 | 44 | 1 | ||

| UA | 2274 | 112-160-320 | 41 | 2 | 3 | |

| UA | 2324 | 320 | 14 | 1 | ||

| UA | 2883 | 117 | 32 | 1 | ||

| UA | 2890 | 260 | 23 | 1 | ||

Alleles in boldface are predominant. NF, allele not found in the FlaA SVR alleles database.

Boldface indicates predominant types. RF, refractory to digestion by SmaI; ND, not done.

UA, unassigned to any CC.

Culture of isolates and DNA extraction for PCR assays and sequencing.

All isolates were stored in FBP medium (17) at −70°C until use. The recovery procedure was carried out in two steps. Without thawing, a loopful of cells scraped from the upper part of the cryotube was plated. Cultures were first grown on mCCDA medium at 41.5°C for 48 h in a microaerobic atmosphere. Next, a subculture was done on chocolate PolyVitex agar (product 43101; BioMerieux, Marcy-l'Etoile, France) at 41.5°C. Bacterial DNA was extracted from this last overnight culture with a DNA QIAamp mini Kit (catalog no. 551304; Qiagen, The Netherlands).

Macrorestriction analysis.

The preparation of PFGE plugs was carried out according to a previously described rapid protocol (36). DNA was digested overnight at 25°C with 25 U of SmaI restriction endonuclease (New England Biolabs, Westburg, The Netherlands) in a final volume of 130 μl. PFGE was performed using a Chef-DRII system (Bio-Rad, CA). Agarose gel (1%) prepared in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer (Sigma-Aldrich Co., Baltimore, MD) was subjected to electrophoresis for 22 h at 200 V and 14°C with ramped pulse times from 10 to 35 s. Images of ethidium bromide-stained gels were captured under UV illumination by a video system (Gel DOC 1000; Bio-Rad).

fla SVR sequencing and MLST.

First, a fla gene template that encompasses the SVR was generated by PCR with the previously described primer pair FLA4F and FLA625RU (29). Sequencing reactions were performed with the forward and reverse primers fla SVR 263f (31) and FLA625RU, respectively. Amplification and sequencing of the seven housekeeping genes for MLST were carried out according to previously developed experimental conditions (9). For both fla SVR sequencing and MLST, PCR products were cleaned up using the ExoSAP-IT treatment (product no. US78201; GE Healthcare, Diegem, Belgium), and sequence extension reactions in BigDye Ready reaction mix (version 3.1; Applied Biosystems, Lennik, Belgium) were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Unincorporated dye terminators were removed by an ethanol precipitation method, and products were analyzed with an ABI Prism 3130 sequencer (Applied Biosystems).

Typing assignment.

PFGE complex groups were defined as follows: in each similarity cluster of 90%, a central profile was identified that differed from other variants in this cluster by one band position. PFGE complex groups were assigned a number, and subtypes (i.e., profiles of variants) are named by the same number plus a letter (for example, type 1 is the central profile of the PFGE complex group 1 and types 1a, 1b, and 1c are variants of this group).

Nucleotide sequence alleles of FlaA SVR types were assigned by submitting data to an Internet-accessible database (http://hercules.medawar.ox.ac.uk/flaA/).

For MLST, sequence types (ST) and clonal complexes (CC) were identified by querying the Internet-accessible database http://pubmlst.org/campylobacter/.

Data analysis.

Electrophoretic patterns from PFGE were compared by means of BioNumerics, version 4.01 (Applied Maths, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium). A dendrogram was constructed to reflect similarities between strains in the matrix and to delineate PFGE complex groups as described above. Analysis was based on band position and derived by the Dice coefficient with a maximum position tolerance of 1%. Strains were clustered by the unweighted pair group method using arithmetic averages. Minimum-spanning trees were constructed using BioNumerics.

The genetic diversity of the three sets of isolates (human, poultry, and bovine) was estimated with two statistical methods applied to MLST data. First, the index of association reflecting the degree of clonality in a population was calculated using the START program (25, 39). An index value differing from zero indicates a clonal population; a value close to zero reflects a linkage equilibrium generated by a freely recombining population.

Rarefaction analysis was performed with a program available on the following website: http://www.uga.edu/∼strata/software/Software.html. This statistical test allows the comparison of ST diversity computed from a collection of isolates of different sizes. A steeper slope of the rarefaction curve indicates a higher degree of diversity.

The index of population differentiation (F statistic, denoted FST) was estimated using Arlequin, version 3.1, software (13). An FST of 0 indicates that two populations are indistinguishable, whereas an FST value of 1 indicates that two populations are genetically distinct.

RESULTS

Prevalence.

Out of 448 cecal samples analyzed from cattle, 55 from 35 farms were positive (12.3%), and all isolates were identified as C. jejuni species. Out of 229 samples analyzed from poultry, 71 were positive for Campylobacter spp. (31%), of which 43.7% and 56.3% were identified by duplex PCR as C. coli and C. jejuni, respectively.

Typing results.

An overview of the typing results from the whole collection of isolates is shown in Table 1. Five isolates were refractory to SmaI digestion, and three isolates could no longer be cultured after a freeze-thaw step. Macrorestriction analysis was completed on 200 isolates, yielding 121 different profiles and 65 PFGE complex groups at a similarity cutoff value of 90%. Up to six variants were identified for the same complex group (groups 3 and 20) (see Fig S1 in the supplemental material). Seventy isolates (35%) were classified in the five most common PFGE complex groups: 1, 3, 20, 11, and 37. Thirty-one PFGE complex groups contained between two and six strains, and 29 PFGE complex groups contained a single strain. The two largest PFGE complex groups, groups 1 and 3, respectively, contained primarily isolates of human (9 and 12 isolates, respectively) and bovine (9 and 6 isolates, respectively) origin compared to a single strain of avian origin in both groups.

The fla SVR sequencing method was successfully applied to 207 of the 208 isolates. A total of 58 fla SVR sequences were identified, corresponding to 23 peptide alleles. Five new nucleotide sequences not previously listed in the website database were found. Four of them corresponded to a peptide allele already described, and the last one was registered as the new allele sequence 1017 and peptide 253. At the nucleotide level, fla type 36 was the most common (11.6%) of the collection, none of which were of poultry origin. Twenty-six fla types out of 58 were detected only once. At the peptide level, 90 isolates (43.5%) had allele 1.

MLST data were available for the whole collection of isolates (208 typing results). A total of 78 different ST were found belonging to 28 CC). Thirteen ST remained unassigned to existing complex groups (Table 1). Ten new ST not previously registered in the Oxford MLST database were identified (numbers 2882 to 2891). Five are of human origin, and three and two are of avian and bovine origin, respectively. The following seven clonal complexes were most frequently observed: CC21 (24%), CC206 (9.1%), CC45 (8.2%), CC257 (6.7%), CC 48 (6.2%), CC353 (5.8%), and CC61 (5.3%). ST19 and ST21 within CC21 were the most frequently observed ST, with 7.2% and 5.8% of isolates, respectively.

Concordance between the three typing methods.

Some MLST CC displayed a marked association with particular PFGE complex groups and/or fla SVR sequence types. Seventy-two percent of CC21 isolates formed part of PFGE complex groups 1 and 3, which are themselves closely related (80% similarity) (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). In addition, 40% of CC21 isolates had fla SVR sequence type 36 (mainly ST19 and ST50). All CC45 isolates were either refractory to SmaI digestion or part of PFGE complex group 20. For CC45, fla SVR type 2 was predominant, with 8 of 13 isolates having this allele (Table 1). Forty-four percent of CC257 formed part of PFGE complex group 24 and had fla SVR type 16. CC48 isolates belong to PFGE complex groups 9, 32, and 37, with PFGE complex groups 9 and 37 themselves closely related (76% similarity) (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). PFGE group 37 was represented by 66.7% of isolates (8/12) of this CC48. In addition, fla SVR type 32 was observed most frequently in this cluster (8/12 isolates). All 11 CC61 strains were associated with PFGE group complex 11, with no particular fla SVR type standing out. Some ST with very similar allele combinations but not assigned to the same CC (based on the Oxford database) clustered around the same PFGE central profile (Table 2) with or without a conserved fla SVR type: ST 2065, 2641, and 2884 shared PFGE group 13 and fla SVR type 14; ST 464 and 2890 shared PFGE group 23 and fla SVR type 260; ST 824 and 2888 shared PFGE group 5; and ST 2324 and 1759 shared PFGE group 14.

TABLE 2.

PFGE grouping from different ST not associated with existing CC

| PFGE complex | PFGE type(s) | No. of isolates | ST no. | MLST allelic profile

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aspA | glnA | gltA | glyA | pgm | tkt | uncA | ||||

| 5 | 5, 5a | 4 | 824 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 11 | 5 | 6 |

| 5 | 1 | 2888 | 114 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 11 | 5 | 6 | |

| 13 | 13 | 1 | 2065 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 23 | 1 | 6 |

| 13a | 1 | 2884 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 23 | 1 | 16 | |

| 13b | 2 | 2641 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 13 | 3 | 6 | |

| 14 | 14 | 1 | 2324 | 7 | 112 | 5 | 62 | 11 | 67 | 6 |

| 14a | 1 | 1759 | 7 | 112 | 5 | 10 | 11 | 67 | 6 | |

| 23 | 23, 23a, 23b | 4 | 464 | 24 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 3 | 1 |

| 23b | 1 | 2890 | 67 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 3 | 1 | |

Genotype diversity recovered within cattle farms.

Samples obtained from different animals on the same cattle farm (slaughtered on the same day) tended to yield different strains: out of 11 farms with multiple (two or three) positive samples, 10 yielded different SVR-PFGE profile combinations.

Diversity and genotype distribution by source/reservoir.

A total of 59, 26, and 22 different ST were identified among the 124, 36, and 48 isolates from the human, poultry, and cattle collection of C. jejuni isolates, respectively. Using a single representative of each ST, the index of association was 0.889 for human, 0.911 for poultry, and 2.157 for cattle isolates.

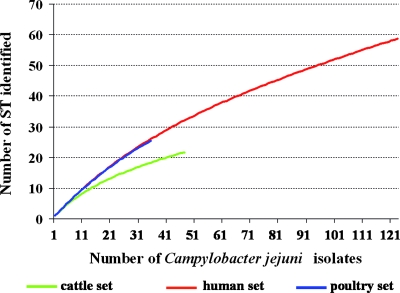

The discrepancy between population structure from cattle isolates and the two other collections was similar by rarefaction curve analysis (Fig. 1): the two slopes for the human and poultry sets appeared similar while that for cattle set was flatter, reflecting a lower genetic diversity.

FIG. 1.

Rarefaction curves of C. jejuni population by origin of isolates.

More than half of the strains from the poultry set (58.3%) and 25% of the cattle set had ST found in the human set (Fig. 2). ST observed in all three sets constituted 20%, 17%, and 42% of isolates from human, poultry, and cattle sets, respectively (Fig. 2). In the same way, 43.5%, 25%, and 33.3% of isolates had ST specific to human, poultry, and cattle sources, respectively. Finally, in the human strain collection, 26.6% and 9.7% of ST were common to poultry and to cattle, respectively (Fig. 2). There was no ST that was recovered from both cattle and poultry and not humans. The minimum spanning tree constructed in Fig. 3 shows the qualitative and quantitative diversity of ST by origin. CC21 is the most frequently observed CC in human (21.8%) and bovine (41.7%) isolates. CC206 and CC353 contain mainly human strains. CC61 contains only bovine and human isolates. Finally, the three last largest groups, CC45, CC48, and CC257, contain isolates from all sources. Thirteen ST were found only in isolates of poultry and human origin (i.e., and not in cattle): ST22, ST51, ST53, ST122, ST305, ST354, ST400, ST464, ST607, ST824, ST879, ST1707, and ST2274 (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

Distribution of ST by origin.

FIG. 3.

Minimum spanning tree of MLST data for the 208 isolates of C. jejuni. Each circle corresponds to a particular ST, and the size of the circle is proportional to the number of isolates sharing the same ST, i.e., the number indicated in the circle (only when the ST is shared by at least three isolates). Inside the circles, the colors reflect the relative number of isolates from each collection: green for cattle, red for human, and blue for poultry. The ST associated to CC as designated on the MLST website from the Oxford database (see Materials and Methods) are linked with the gray areas, and only the main ones are visualized. Designation of these CC are indicates beside. CC206, divided among the ST 46, 122, 290, 572, and 2104, is so close to CC21 that it is not shown as a separate entity on the figure.

Population differentiation estimated by the FST value was highest between the poultry and cattle collection (0.09432, P = 0.00001), intermediate between cattle and human collection (0.03955, P = 0.00037), and lowest between poultry and human collection (0.01902, P = 0.01779).

Temporal distribution of human ST.

The most frequently observed ST from the human collection were ST572 with seven isolates; ST21, ST19, ST50, and ST824 with six isolates each; and ST45 and ST400 with five isolates each. Overall, CC21 predominated, with 27 isolates distributed over eight ST. Figure 4 shows the number of weekly ST of human C. jejuni cases during the summer season in 2006. No ST was observed three times or more per week, and no clustering over time was apparent. One can also observe a high diversity of ST during weeks 31 and 32, representing the first two weeks of August.

FIG. 4.

Epidemic curve of weekly reported human Campylobacter cases during the summer period of 2006 in Luxembourg by sequence types as defined by MLST. Only ST with at least four cases during this period are shown by different colors.

DISCUSSION

The aim of our study was to implement a surveillance from June to September on human cases with two main objectives: (i) to rapidly detect potential outbreak and (ii) to identify possible sources and/or provide a better understanding of their relative contributions to this phenomenon of case intensification.

C. jejuni infections occur each year, with a seasonal peak during summer in Luxembourg. The high diversity of strains confirms the common opinion that most cases are sporadic and that, even during the summer peak, human Campylobacter cases in Luxembourg are unlikely to be due to the same source. It is tempting to speculate that a sizeable fraction of cases are travel related although some caution in overinterpreting these data is warranted, and further epidemiological data should be collected to verify this claim.

Retail poultry and cattle cecal contents were examined in an attempt to identify potential overlaps between the animal and human populations. In order to ensure a best overview of the different clonal types in situ, an isolation strategy using two plating media in parallel was tested on the bovine samples, and farms were examined more than once. Previous studies have shown that several genotypes can coexist among individual cattle (20) or chickens (38) and that individual farms or herds can be contaminated with multiple clones (37, 41). The authors of previous studies stressed the importance of trying to recover the underlying strain diversity and to analyze more than one isolate per sample for epidemiological investigations. Our results confirm that colonization of different animals on the same farm/flocks with different genotypes occurs quite frequently. Whether this strain diversity observed at the farm level directly translates to the strain diversity observed at the human level deserves further attention.

In our study we did not detect an effect of multiple plating media on selection of clones, and the same strain was generally recovered with both media. However, the enrichment step in Preston broth has been shown to give a selective advantage to C. coli at the expense of C. jejuni when both species are present in the sample (7). Depending on the competing clones, this enrichment step could play a similar role in promoting the overgrowth of certain strains. By examining one isolate per plate, the most predominant clone selected in vitro is taken into account. Thus, for future work, it would be interesting to streak the sample directly prior to enrichment and then pick a sufficient number of colonies afterwards on plating media when possible.

One of the major limitations of our study was the quite low prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in retail chicken samples, resulting in relatively few poultry isolates available for typing. Other recent studies have found Campylobacter prevalence near to or exceeding 50% (6, 18, 19, 30), but the setting was in different countries with methodologies different from ours, in particular, sample type (whole raw chicken and cuts with and without skin) and initial suspension (test portion weight and whole-carcass rinse) prior to the enrichment step. A standardized procedure as proposed by the European Food Safety Authority (12) would be interesting to evaluate in the future research work.

To identify in real time clusters of human infections, the fla SVR typing system was used as a surveillance tool in our study. Despite the known instability of this molecular marker, previous studies have suggested that its use within a short defined space-time window was appropriate for the rapid detection of linked clusters (4, 29). With 45 different fla SVR sequences identified among the 124 human isolates collected, a substantial genetic diversity was observed. fla type 14 and fla type 36 were most frequently represented with 9.7% and 11.3% of all isolates, respectively. However, their distribution on the time scale was significantly dispersed and indicated the sporadic nature of the human cases during summer 2006 in Luxembourg.

By giving a fingerprint of the whole genome, the macrorestriction analysis provides useful complementary information to locus-based methods like MLST. With the development of a simple and rapid protocol (36), its implementation became convenient. However, the interpretation of PFGE data, in particular, needs to take into account the inherent instability of the Campylobacter genome. Genetic changes of a clone have been shown to take place in vivo either during intestinal colonization of animals (22) or during the course of infection in humans (42). By contrast, these shifts did not occur in vitro after serial subcultures (28, 42). In this context where microevolutions are quite frequent, grouping of profiles into PFGE complex groups is thus a useful technique and appears to be justified for tracing clones. In MLST, CC were previously defined with the BURST algorithm (8, 9), and the reliability of this method with regard to the rate of recombination and mutation was verified (47). The diversity revealed by MLST in our studies has been largely consistent with previous investigations. Predominant CC found in human isolates (CC21, CC206, CC353, CC45, CC257, CC48, and CC354) have been described, particularly from Europe (8, 40). CC21 and CC61 have been frequently observed among C. jejuni isolates of bovine origin (8, 15, 26, 38). By contrast, no dominant CC were observed in our set of poultry isolates but, instead, a greater diversity, in accordance with previous surveys (9, 28, 38). The lower genetic diversity of isolates of bovine origin could be due to the fact that cecal samples were obtained from farms located in Luxembourg only, whereas the geographic origin of retail poultry meat was much more diverse as it included samples from Belgium, France, Portugal, and Luxembourg. Nevertheless, in both cases, the sampling procedure was in accordance with the Campylobacter strains circulating in the country. Population pairwise FST comparisons revealed little genetic differentiation between animals and clinical isolates and highlighted, in particular, the marked overlap between poultry and human collection. On the other hand, the highest FST value observed between the bovine and poultry sets of isolates supports the idea that certain CC tend to be preferentially associated with different hosts.

One on the most relevant findings of our study is the concordance we observed between PFGE complex groups and MLST CC. All strains belonging to CC61 were also associated with PFGE complex group 11. Our study along with the work of other authors has found that this CC was strongly linked with cattle and infrequently represented in isolates from poultry (8, 15, 18, 26, 28). As such, the genetic stability of this lineage might be due to a successful ecological niche adaptation in the intestine of ruminants. This specificity suggests that the two sporadic cases in humans during summer were probably linked with an undetermined cattle source.

Similarly, genotyping results for isolates of CC21, overrepresented in our cattle collection and predominantly identified among human cases, were concordant by PFGE. In addition, fla SVR sequence type 36 appeared to be restricted to isolates of human or bovine origin. Again, a significant stability in the genome was highlighted and strongly supports the idea that the members of this group of C. jejuni are clonally related. Even if 75% of the poultry ST can also be found in humans, cattle could thus be an underrecognized reservoir of C. jejuni infections. Other epidemiological investigators (15, 38) have suggested that bovine herds could be a source involved in the global contamination cycle of Campylobacter via environmental routes rather than a direct source of infections for humans via the consumption of beef. Seasonal variation in animal shedding was observed to be less important during the winter period. The seasonal increase of the prevalence of C. jejuni in bovine intestines seems to coincide with the grazing period during which the animals are in contact with potentially contaminated surface waters (20, 41). Flies and wild rabbits have also been proposed as possible vectors for spreading Campylobacter in the environment (11, 15, 44). In Denmark, the contamination of broiler flocks by flies was shown (21), which could partially explain the summer peak of human cases through the consumption or mishandling of contaminated poultry products.

The results of our study confirm that while retail poultry products remain a substantial source of human infections, cattle probably act as an unexpected reservoir of C. jejuni that could play a major role. However, a large proportion of our human isolates (43.5%) have ST not found in either poultry or cattle sources. The roles of environmental factors and of pet animals (5) need to be further investigated in order to better determine their relative contributions to human campylobacteriosis. This will become possible only when future large epidemiological case control studies make use of increasingly available genotyping information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is a part of the EPIFOOD project funded by the National Research Fund of Luxembourg.

We acknowledge Jessica Tapp and Marion Rommes for technical assistance in isolating and identifying Campylobacter strains and Fabrice Dulac for sampling at abattoirs and retail. We gratefully acknowledge Jeremie Langlet for technical computer assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 17 October 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alm, R. A., P. Guerry, and T. J. Trust. 1993. Distribution and polymorphism of the flagellin genes from isolates of Campylobacter coli and Campylobacter jejuni. J. Bacteriol. 175:3051-3057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altekruse, S. F., N. J. Stern, P. I. Fields, and D. L. Swerdlow. 1999. Campylobacter jejuni—an emerging foodborne pathogen. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 5:28-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butzler, J. P., and J. Oosterom. 1991. Campylobacter: pathogenicity and significance in foods. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 12:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark, C. G., L. Bryden, W. R. Cuff, P. L. Johnson, F. Jamieson, B. Ciebin, and G. Wang. 2005. Use of the oxford multilocus sequence typing protocol and sequencing of the flagellin short variable region to characterize isolates from a large outbreak of waterborne Campylobacter sp. strains in Walkerton, Ontario, Canada. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:2080-2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Damborg, P., K. E. Olsen, E. Moller Nielsen, and L. Guardabassi. 2004. Occurrence of Campylobacter jejuni in pets living with human patients infected with C. jejuni. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:1363-1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Denis, M., J. Refregier-Petton, M. J. Laisney, G. Ermel, and G. Salvat. 2001. Campylobacter contamination in French chicken production from farm to consumers. Use of a PCR assay for detection and identification of Campylobacter jejuni and Camp. coli. J. Appl. Microbiol. 91:255-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Denis, M., C. Soumet, K. Rivoal, G. Ermel, D. Blivet, G. Salvat, and P. Colin. 1999. Development of a m-PCR assay for simultaneous identification of Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 29:406-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dingle, K. E., F. M. Colles, R. Ure, J. A. Wagenaar, B. Duim, F. J. Bolton, A. J. Fox, D. R. Wareing, and M. C. Maiden. 2002. Molecular characterization of Campylobacter jejuni clones: a basis for epidemiologic investigation. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:949-955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dingle, K. E., F. M. Colles, D. R. Wareing, R. Ure, A. J. Fox, F. E. Bolton, H. J. Bootsma, R. J. Willems, R. Urwin, and M. C. Maiden. 2001. Multilocus sequence typing system for Campylobacter jejuni. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:14-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duim, B., T. M. Wassenaar, A. Rigter, and J. Wagenaar. 1999. High-resolution genotyping of Campylobacter strains isolated from poultry and humans with amplified fragment length polymorphism fingerprinting. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2369-2375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ekdahl, K., B. Normann, and Y. Andersson. 2005. Could flies explain the elusive epidemiology of campylobacteriosis? BMC Infect. Dis. 5:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.European Food Safety Authority. 2006. Report of Task Force on Zoonoses Data Collection on proposed technical specifications for a coordinated monitoring programme for Samonella and Campylobacter in broiler meat in the EU. EFSA J. 92:1-33. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Excoffier, L., G. Laval, and S. Schneider. 2005. Arlequin ver. 3.0: an integrated software package for population genetics data analysis. Evol. Bioinformatics Online 1:47-50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fisher, I. S., and S. Meakins, on behalf of the Enter-net participants. 2006. Surveillance of enteric pathogens in Europe and beyond: Enter-net annual report for 2004. Euro. Surveill. 11:E060824.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.French, N., M. Barrigas, P. Brown, P. Ribiero, N. Williams, H. Leatherbarrow, R. Birtles, E. Bolton, P. Fearnhead, and A. Fox. 2005. Spatial epidemiology and natural population structure of Campylobacter jejuni colonizing a farmland ecosystem. Environ. Microbiol. 7:1116-1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibson, J., E. Lorenz, and R. J. Owen. 1997. Lineages within Campylobacter jejuni defined by numerical analysis of pulsed-field gel electrophoretic DNA profiles. J. Med. Microbiol. 46:157-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gorman, R., and C. C. Adley. 2004. An evaluation of five preservation techniques and conventional freezing temperatures of −20 degrees C and −85 degrees C for long-term preservation of Campylobacter jejuni. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 38:306-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gormley, F. J., M. Macrae, K. J. Forbes, I. D. Ogden, J. F. Dallas, and N. J. Strachan. 2008. Has retail chicken played a role in the decline of human campylobacteriosis? Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:383-390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Habib, I., I. Sampers, M. Uyttendaele, D. Berkvens, and L. De Zutter. 2008. Baseline data from a Belgium-wide survey of Campylobacter species contamination in chicken meat preparations and considerations for a reliable monitoring program. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:5483-5489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hakkinen, M., H. Heiska, and M. L. Hanninen. 2007. Prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in cattle in Finland and antimicrobial susceptibilities of bovine Campylobacter jejuni strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:3232-3238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hald, B., H. Skovgard, D. D. Bang, K. Pedersen, J. Dybdahl, J. B. Jespersen, and M. Madsen. 2004. Flies and Campylobacter infection of broiler flocks. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10:1490-1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanninen, M. L., M. Hakkinen, and H. Rautelin. 1999. Stability of related human and chicken Campylobacter jejuni genotypes after passage through chick intestine studied by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2272-2275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harrington, C. S., F. M. Thomson-Carter, and P. E. Carter. 1997. Evidence for recombination in the flagellin locus of Campylobacter jejuni: implications for the flagellin gene typing scheme. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2386-2392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Humphrey, T., S. O'Brien, and M. Madsen. 2007. Campylobacters as zoonotic pathogens: a food production perspective. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 117:237-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jolley, K. A., E. J. Feil, M. S. Chan, and M. C. Maiden. 2001. Sequence type analysis and recombinational tests (START). Bioinformatics 17:1230-1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karenlampi, R., H. Rautelin, D. Schonberg-Norio, L. Paulin, and M. L. Hanninen. 2007. Longitudinal study of Finnish Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli isolates from humans, using multilocus sequence typing, including comparison with epidemiological data and isolates from poultry and cattle. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:148-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maiden, M. C., J. A. Bygraves, E. Feil, G. Morelli, J. E. Russell, R. Urwin, Q. Zhang, J. Zhou, K. Zurth, D. A. Caugant, I. M. Feavers, M. Achtman, and B. G. Spratt. 1998. Multilocus sequence typing: a portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:3140-3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manning, G., B. Duim, T. Wassenaar, J. A. Wagenaar, A. Ridley, and D. G. Newell. 2001. Evidence for a genetically stable strain of Campylobacter jejuni. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:1185-1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meinersmann, R. J., L. O. Helsel, P. I. Fields, and K. L. Hiett. 1997. Discrimination of Campylobacter jejuni isolates by fla gene sequencing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2810-2814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meldrum, R. J., and I. G. Wilson. 2007. Salmonella and Campylobacter in United Kingdom retail raw chicken in 2005. J. Food Prot. 70:1937-1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mellmann, A., J. Mosters, E. Bartelt, P. Roggentin, A. Ammon, A. W. Friedrich, H. Karch, and D. Harmsen. 2004. Sequence-based typing of flaB is a more stable screening tool than typing of flaA for monitoring of Campylobacter populations. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:4840-4842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moore, J. E., D. Corcoran, J. S. Dooley, S. Fanning, B. Lucey, M. Matsuda, D. A. McDowell, F. Megraud, B. C. Millar, R. O'Mahony, L. O'Riordan, M. O'Rourke, J. R. Rao, P. J. Rooney, A. Sails, and P. Whyte. 2005. Campylobacter. Vet. Res. 36:351-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murphy, C., C. Carroll, and K. N. Jordan. 2006. Environmental survival mechanisms of the foodborne pathogen Campylobacter jejuni. J. Appl. Microbiol. 100:623-632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Notermans, S., and M. Borgdorff. 1997. A global perspective of foodborne disease. J. Food Prot. 60:1395-1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.On, S. L. 1998. In vitro genotypic variation of Campylobacter coli documented by pulsed-field gel electrophoretic DNA profiling: implications for epidemiological studies. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 165:341-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ribot, E. M., C. Fitzgerald, K. Kubota, B. Swaminathan, and T. J. Barrett. 2001. Rapid pulsed-field gel electrophoresis protocol for subtyping of Campylobacter jejuni. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:1889-1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rivoal, K., C. Ragimbeau, G. Salvat, P. Colin, and G. Ermel. 2005. Genomic diversity of Campylobacter coli and Campylobacter jejuni isolates recovered from free-range broiler farms and comparison with isolates of various origins. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:6216-6227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schouls, L. M., S. Reulen, B. Duim, J. A. Wagenaar, R. J. Willems, K. E. Dingle, F. M. Colles, and J. D. Van Embden. 2003. Comparative genotyping of Campylobacter jejuni by amplified fragment length polymorphism, multilocus sequence typing, and short repeat sequencing: strain diversity, host range, and recombination. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:15-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith, J. M., N. H. Smith, M. O'Rourke, and B. G. Spratt. 1993. How clonal are bacteria? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:4384-4388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sopwith, W., A. Birtles, M. Matthews, A. Fox, S. Gee, M. Painter, M. Regan, Q. Syed, and E. Bolton. 2006. Campylobacter jejuni multilocus sequence types in humans, northwest England, 2003-2004. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12:1500-1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stanley, K., and K. Jones. 2003. Cattle and sheep farms as reservoirs of Campylobacter. J. Appl. Microbiol. 94(Suppl.):104S-113S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steinbrueckner, B., F. Ruberg, and M. Kist. 2001. Bacterial genetic fingerprint: a reliable factor in the study of the epidemiology of human campylobacter enteritis? J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4155-4159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suerbaum, S., M. Lohrengel, A. Sonnevend, F. Ruberg, and M. Kist. 2001. Allelic diversity and recombination in Campylobacter jejuni. J. Bacteriol. 183:2553-2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Szalanski, A. L., C. B. Owens, T. McKay, and C. D. Steelman. 2004. Detection of Campylobacter and Escherichia coli O157:H7 from filth flies by polymerase chain reaction. Med. Vet. Entomol. 18:241-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tauxe, R. V. 1997. Emerging foodborne diseases: an evolving public health challenge. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 3:425-434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tauxe, R. V. 2002. Emerging foodborne pathogens. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 78:31-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Turner, K. M., W. P. Hanage, C. Fraser, T. R. Connor, and B. G. Spratt. 2007. Assessing the reliability of eBURST using simulated populations with known ancestry. BMC Microbiol. 7:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vellinga, A., and F. Van Loock. 2002. The dioxin crisis as experiment to determine poultry-related campylobacter enteritis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:19-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang, Y., W. M. Huang, and D. E. Taylor. 1993. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of the Campylobacter jejuni gyrA gene and characterization of quinolone resistance mutations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:457-463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang, Y., and D. E. Taylor. 1990. Natural transformation in Campylobacter species. J. Bacteriol. 172:949-955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wassenaar, T. M., B. Geilhausen, and D. G. Newell. 1998. Evidence of genomic instability in Campylobacter jejuni isolated from poultry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:1816-1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wilson, D. L., J. A. Bell, V. B. Young, S. R. Wilder, L. S. Mansfield, and J. E. Linz. 2003. Variation of the natural transformation frequency of Campylobacter jejuni in liquid shake culture. Microbiology 149:3603-3615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.