Abstract

Background and purpose:

Recent evidence has suggested that pilocarpine (ACh receptor agonist) injected peripherally may act centrally producing salivation and hypertension. In this study, we investigated the effects of specific M1 (pirenzepine), M2/M4 (methoctramine), M1/M3 (4-DAMP) and M4 (tropicamide) muscarinic receptor subtype antagonists injected into the lateral cerebral ventricle (LV) on salivation, water intake and pressor responses to peripheral pilocarpine.

Experimental approach:

Male Holtzman rats with stainless steel cannulae implanted in the LV were used. Salivation was measured in rats anaesthetized with ketamine (100 mg per kg body weight) and arterial pressure was recorded in unanaesthetized rats.

Key results:

Salivation induced by i.p. pilocarpine (4 μmol per kg body weight) was reduced only by 4-DAMP (25–250 nmol) injected into the LV, not by pirenzepine, methoctramine or tropicamide at the dose of 500 nmol. Pirenzepine (0.1 and 1 nmol) and 4-DAMP (5 and 10 nmol) injected into the LV reduced i.p. pilocarpine-induced water intake, whereas metoctramine (50 nmol) produced nonspecific effects on ingestive behaviours. Injection of pirenzepine (100 nmol) or 4-DAMP (25 and 50 nmol) into the LV reduced i.v. pilocarpine-induced pressor responses. Tropicamide (500 nmol) injected into the LV had no effect on pilocarpine-induced salivation, pressor responses or water intake.

Conclusions and implications:

The results suggest that central M3 receptors are involved in peripheral pilocarpine-induced salivation and M1 receptors in water intake and pressor responses. The involvement of M3 receptors in water intake and pressor responses is not clear because 4-DAMP blocks both M1 and M3 receptors.

Keywords: muscarinic receptors, M1 and M3 receptors, salivary glands, arterial pressure, thirst

Introduction

The ACh receptor agonist pilocarpine stimulates salivary secretion and is useful for the treatment of dryness of the oral mucosa in patients affected by salivary gland diseases (Ferguson, 1993; Wiseman and Faulds, 1995, Fox et al., 2001). It is well accepted that pilocarpine stimulates salivary secretion by acting directly on ACh receptors in the salivary glands, an effect supported by the sialagogue response to pilocarpine in isolated salivary glands (Compton et al., 1981). Pilocarpine easily crosses the blood–brain barrier (Freedman et al., 1989) and systemic administration also facilitates salivation by acting centrally, as suggested by studies showing that salivation to i.p. pilocarpine is reduced by forebrain lesions in the preoptic periventricular tissue surrounding the anteroventral third ventricle (AV3V) region, lateral hypothalamus or medial preoptic area (Renzi et al., 1993, 2002; Lopes de Almeida et al., 2006). In spite of some discrepancies (Sato et al., 2006), the nonspecific ACh receptor antagonist atropine methyl bromide injected intracerebroventricularly at doses that act only centrally also reduces i.p. pilocarpine-induced salivation (Takakura et al., 2003).

Besides salivation, pilocarpine also produces cardiovascular responses and induces water intake (Gay et al., 1976; Sanchez and Méier, 1993; Moreira et al., 2003; Takakura et al., 2005). Some of these responses depend exclusively on the central action of pilocarpine, and others are the result of a mix of central and peripheral actions of pilocarpine. Peripheral injections of pilocarpine induce a transitory hypotension (less than 1 min of duration) followed by an unexpected long-lasting pressor response (Sanchez and Méier, 1993; Moreira et al., 2003; Takakura et al., 2005). The effect of i.p. pilocarpine changes from pressor to depressor response in AV3V-lesioned rats, suggesting that the increase in arterial pressure depends on the central action of pilocarpine (Takakura et al., 2005).

It is well established that ACh agonists acting in the brain induce water intake (Grossman, 1960; Fisher and Coury, 1962; Levitt and Fisher, 1966; Giardina and Fisher, 1971; Menani et al., 1990; Rowland et al., 2003). However, water intake to peripheral injections of ACh agonists may depend on the activation of renin–angiotensin mechanisms due to hypotension (Gay et al., 1976; Fregly et al., 1982; Rowland et al., 2003). Because peripheral pilocarpine induces hypertension, the renin–angiotensin system is probably not activated in this case and water intake may depend on the direct activation of central mechanisms.

Of the five muscarinic ACh receptor subtypes described (Brann et al., 1993), at least four of them (M1–M4) can be detected in the rat brain (Messer et al., 1989; Zubieta and Frey, 1993; Tice et al., 1996). Pilocarpine has a different affinity for each muscarinic receptor subtype; however, depending on the dose, it can activate all of them (Mayorga et al., 1998). The M3 receptors are thought to control salivary gland secretion and vasodilatation in different tissues (Iwabuchi et al., 1994). Central M1 and M3 receptors are involved in ACh agonist-induced water intake (Massi et al., 1989; Polidori et al., 1990; Rowland et al., 2003), and central M1 receptors are also thought to be involved in pressor responses (Aslan et al., 1997; Pelat et al., 1999).

Although peripheral injection of pilocarpine may act centrally to produce salivation, water intake and pressor responses, it is still not known which muscarinic receptor subtypes are involved in these responses. In this study, we investigated the effects of specific M1 (pirenzepine), M2/M4 (methoctramine), M1/M3 (4-DAMP) and M4 (tropicamide) muscarinic receptor subtype antagonists injected intracerebroventricularly (lateral ventricle) on salivation, water intake and cardiovascular responses induced by pilocarpine injected peripherally in rats.

Methods

Animals

Male Holtzman rats weighing 280–320 g were used. The animals were housed individually in stainless steel cages in a room with controlled temperature (23±2 °C) and humidity (55±10%). Lights were on from 0700 to 1900 hours. Guabi rat chow (Paulínia, São Paulo, Brazil) and tap water were available ad libitum. The Ethical Committee for Animal Care and Use from Dentistry School of Araraquara–UNESP approved the experimental protocols used in this study.

Brain surgery

The animals were anaesthetized with ketamine (80 mg per kg body weight) combined with xylazine (7 mg per kg body weight) and placed in a Kopf stereotaxic instrument (model 900, David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA, USA). with the bregma and lambda points at the same horizontal plane. A stainless steel cannula (10 × 0.7 mm OD) was implanted into the lateral cerebral ventricle (LV) using the coordinates 0.3 mm caudal to bregma, 1.5 mm lateral to midline and 3.6 mm below the dura mater. The cannula was fixed to the cranium by dental acrylic resin and jeweler screws. A prophylactic dose of penicillin (50 000 iu) was given intramuscularly at the beginning of surgery. The analgesic/anti-inflammatory ketoprofen (0.3 mg for each rat) was injected subcutaneously immediately after the surgery. Tests started 5 days after the cerebral surgery.

Cerebral injections

Injections into the LV were made using a 10 μL Hamilton syringe connected by polyethylene tubing (PE-10) to an injection cannula that extended 2 mm beyond the tip of the guide cannula. The drugs were dissolved in isotonic saline, except 4-DAMP, which was dissolved in DMSO at doses above 100 nmol. The volume of injections into the LV was 1–3 μL.

Drugs

Pilocarpine (ACh receptor agonist from Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, USA) at the dose of 4 μmol per kg body weight was injected i.p. or intravenously. Pirenzepine (muscarinic M1 antagonist from Sigma Chemical Co.), 0.1–500 nmol; methoctramine tetrahydrochloride (muscarinic M2/M4 antagonist from RBI, USA), 10–500 nmol 4-DAMP methiodide (muscarinic M1/M3 antagonist from RBI), 2.5–250 nmol; and tropicamide (muscarinic M4 antagonist from RBI, Natick, MA, USA), 500 nmol, were injected intracerebroventricularly.

The dose of pilocarpine used (4 μmol per kg body weight) was based on the results from previous studies that investigated the effects of i.p. pilocarpine on salivation and arterial pressure (Renzi et al., 1993, 2002; Moreira et al., 2003; Takakura et al., 2003, 2005; Lopes de Almeida et al., 2006).

Ketamine was obtained from Cristalia (Itapira, São Paulo, Brazil) and xylazine from Agener Uniao (Embu-Guaçu, São Paulo, Brazil).

Salivation

The rats were anaesthetized with ketamine (100 mg per kg body weight, i.p.) and received an injection of saline or a muscarinic antagonist intracerebroventricularly, followed 15 min later by an i.p. injection of pilocarpine (4 μmol per kg body weight). Ten minutes after pilocarpine injection, the oral cavity was wiped with cotton and four cotton balls, pre-weighed to the nearest 0.0001 g, were inserted into the oral cavity of each animal: two underneath the tongue and two bilaterally medial to the teeth and oral mucosa. The cotton balls were removed 7 min later and the amount of saliva produced was calculated as the change in the weight of the cotton balls. Each rat was tested twice, once after an i.c.v. injection of muscarinic antagonist and once after vehicle i.c.v., both followed by i.p. pilocarpine. Rats were tested in a counterbalanced order, with a 3-day interval between experiments.

Water intake

On test days, food was removed from the home cage. Water intake was recorded every 15 min for 1 h, starting immediately after the i.p. injection of pilocarpine (4 μmol per kg body weight), using burettes with 0.1 mL divisions.

Muscarinic antagonists or vehicle was injected intracerebroventricularly 15 min before pilocarpine. One group of animals was used to test each dose of the antagonists. In the first test, half of the animals received saline+pilocarpine and the other half the muscarinic antagonist+pilocarpine. In the following test, using the same animals, the same protocol was performed in a counterbalanced design. At the end of the two tests, all the animals of the group received the two treatments.

Sodium intake

To show that the effects of central muscarinic blockade on i.p. pilocarpine-induced water intake were not due to nonspecific inhibition of ingestive behaviours, we tested the effects of i.c.v. injections of muscarinic antagonists on 24 h sodium depletion-induced 0.3 M NaCl intake. For this test, rats were maintained for at least 5 days with water, regular chow and 0.3 M NaCl available. After this period, rats received a s.c. injection of the diuretic furosemide (20 mg per kg body weight) followed by sodium-deficient food (powdered corn meal, 0.001% sodium, 0.33% potassium) and water available for 24 h. After 24 h of sodium depletion, the rats received an i.c.v. injection of the muscarinic antagonist or saline. After 15 min, rats had access to water and 0.3 M NaCl for the next hour. The rats received i.c.v. injections of saline, pirenzepine (0.1 nmol), 4-DAMP (5 nmol) or methoctramine (50 nmol) in four different tests. In each test, the group of rats was divided in two and each half of the group received one of the four treatments indicated above. The sequence of the treatments in different tests was randomized and at the end of four tests all the animals received all the four treatments.

Arterial pressure and heart rate recordings

Mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate (HR) were recorded in unanaesthetized rats. Five days after brain surgery, rats were anaesthetized again with ketamine (80 mg per kg body weight) combined with xylazine (7 mg per kg body weight). A polyethylene tubing (PE-10 connected to a PE-50) was inserted into the abdominal aorta through the femoral artery to record arterial pressure and a second polyethylene tubing was inserted into the femoral vein for pilocarpine or saline administration. Arterial and venous catheters were tunnelled subcutaneously and exposed on the back of the rat to allow access in unrestrained, freely moving rats.

On the next day, pulsatile arterial pressure, MAP and HR were recorded in unanaesthetized rats by connecting the arterial catheter to a Statham Gould (P23Db) pressure transducer coupled to a pre-amplifier (model ETH-200 Bridge Bio Amplifier, CB Sciences, Dover, NH, USA) that was connected to a Powerlab computer data acquisition system (model Powerlab 16SP, ADInstruments, Castle Hill, Australia). Baseline MAP and HR were recorded for 20 min before the injections were started and for 1 h more after the injections. The antagonists or vehicle were injected intracerebroventricularly 15 min before i.v. pilocarpine. One group of animals was used to test each dose of the antagonists. On the first day, half of the animals received saline+pilocarpine and the other half the muscarinic antagonist+pilocarpine. On the next day, using the same animals, the same protocol was performed in a counterbalanced design. At the end of the tests, all the animals of the group received the two treatments. Arterial pressure and HR were also analysed in control groups of rats that received saline i.c.v.+saline i.v.

Pilocarpine intravenously produced a transitory hypotension (less than 1 min) followed by a long-lasting pressor response. Therefore, the peaks of maximum hypotension and hypertension were analysed separately.

Histology

At the end of the experiments, the animals were deeply anaesthetized with sodium thiopental (70 mg per kg body weight) and perfused through the heart with saline followed by 10% formalin. The brains were removed, frozen, cut coronally into 50 μm sections and stained with Giemsa stain. Only animals with injections into the LV were considered for statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means±s.e.means. One-way ANOVA was used to analyse salivation, MAP and HR data, and two-way repeated-measure ANOVA was used to analyse water intake. In both cases, ANOVA was followed by Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc test. The peaks of hypotensive and hypertensive responses to i.v. pilocarpine were analysed separately. The effect of each dose of the antagonists on pilocarpine-induced water intake was compared only with the respective control (vehicle+pilocarpine). Significance level was set at P<0.05.

Results

Effects of central muscarinic blockade on i.p. pilocarpine-induced salivation

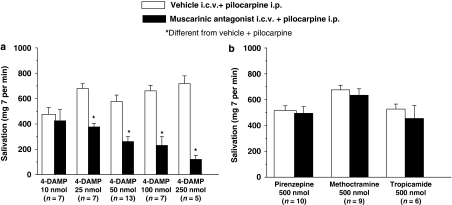

Injections of pilocarpine (4 μmol per kg body weight, i.p.) induced strong salivation that ranged from 476±54 to 718±61 mg per 7 min. Injections of 4-DAMP (25, 50, 100 and 250 nmol) reduced pilocarpine-induced salivation in a dose-dependent manner (F(9, 64)=18.28; P<0.001) (Figure 1a). Injections of 4-DAMP (10 nmol) intracerebroventricularly (Figure 1a) or pirenzepine (500 nmol), methoctramine (500 nmol) or tropicamide (500 nmol) intracerebroventricularly did not alter i.p. pilocarpine-induced salivation (F(5, 44)=2.67; P>0.05) (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Salivation (mg per 7 min) induced by i.p. injection of pilocarpine (4 μmol per kg body weight) in rats pretreated with (a) i.c.v. 4-DAMP (10, 25, 50, 100 and 250 nmol) or i.c.v. saline; (b) i.c.v. pirenzepine (500 nmol), i.c.v. methoctramine (500 nmol) or i.c.v. tropicamide (500 nmol) or i.c.v. saline. The results are presented as means±s.e.mean; n=number of rats.

Effects of central muscarinic blockade on i.p. pilocarpine-induced water intake

Pirenzepine at doses of 0.1 nmol (F(1, 7)=54.64; P<0.001) and 1 nmol (F(1, 5)=9.77; P<0.05) (Figure 2a), methoctramine (50 nmol) (F(1, 7)=15.73; P<0.01) (Figure 2b) and 4-DAMP (5 nmol) (F(1, 5)=28.41; P<0.005) and 10 nmol (F(1, 6)=22.06; P<0.005) (Figure 2c) injected intracerebroventricularly reduced water intake induced by i.p. pilocarpine (4 μmol per kg body weight). Pirenzepine (0.05 nmol), methoctramine (10 and 25 nmol), 4-DAMP (2.5 nmol) and tropicamide (500 nmol) injected intracerebroventricularly did not alter i.p. pilocarpine-induced water intake (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Water intake induced by the injection of pilocarpine (4 μmol per kg body weight) i.p. in rats pretreated with (a) i.c.v. pirenzepine (0.05, 0.1 and 1 nmol), (b) i.c.v. methoctramine (10, 25 and 50 nmol), (c) i.c.v. 4-DAMP (2.5, 5 and 10 nmol) and (d) i.c.v. tropicamide (500 nmol) or i.c.v. saline. The results are represented as means±s.e.mean; n=number of rats.

Effects of central muscarinic blockade on sodium depletion-induced sodium intake

To determine whether the effects of central muscarinic blockade on i.p. pilocarpine-induced water intake are specific for pilocarpine-induced water intake or due to nonspecific inhibition of ingestive behaviours, we tested the effects of i.c.v. injections of muscarinic antagonists on sodium depletion-induced 0.3 M NaCl intake. Intracerebroventricular injections of pirenzepine (0.1 nmol) or 4-DAMP (5 nmol) produced no change on sodium depletion-induced 0.3 M NaCl intake (Table 1). Methoctramine (50 nmol) intracerebroventricularly reduced sodium depletion-induced 0.3 M NaCl intake (F(1, 8)=6.56; P<0.05) (Table 1), suggesting that methoctramine may have a nonspecific inhibitory effect on ingestive behaviours.

Table 1.

Effects of muscarinic antagonists injected i.c.v. on cumulative 0.3 M NaCl intake induced by 24 h of sodium depletion

| Treatment |

0.3 M NaCl intake |

|

|---|---|---|

| 30 min | 60 min | |

| Saline | 13.6±2.7 | 12.2±2.9 |

| Pirenzepine | 8.0±1.8 | 9.4±2.1 |

| 4-DAMP | 17.5±0.7 | 17.6±0.7 |

| Methoctramine | 5.6±1.9a | 6.6±2.2a |

The results are represented as means±s.e.mean.

Doses: pirenzepine (0.1 nmol), 4-DAMP (5 nmol) and methoctramine (50 nmol). n=9 rats.

Different from saline (P<0.05).

Effects of central muscarinic blockade on i.p. pilocarpine-induced pressor responses

Pilocarpine (4 μmol per kg body weight, i.v.) induced transitory (less than 1 min) hypotensive responses and long-lasting (around 60 min) pressor responses, without changes in HR (Figure 3, Table 2). For all groups tested, the peak of the hypotensive responses to i.v. pilocarpine ranged from −30±9 to −44±3 mm Hg and the peak of the pressor responses ranged from 40±5 to 53±4 mm Hg. The hypotensive responses started 4 s, and reached a maximum peak at around 8 s, after i.v. pilocarpine. The pressor responses started 1–2 min after i.v. pilocarpine, reached a maximum peak at around 6 min and returned to baseline levels at around 60 min after the injection.

Figure 3.

Changes in mean arterial pressure (MAP) produced by i.v. injection of pilocarpine (4 μmol per kg body weight) in rats pretreated with (a) i.c.v. pirenzepine (25, 50 and 100 nmol), (b) i.c.v. 4-DAMP (10, 25 and 50 nmol), (c) i.c.v. methoctramine (25 and 50 nmol) and (d) i.c.v. tropicamide (500 nmol) or i.c.v. saline. The results are represented as means±s.e.mean; n=number of rats.

Table 2.

Changes in HR after i.v. injections of saline or pilocarpine in rats pretreated, i.c.v., with saline or the muscarinic acetylcholine receptor antagonists

| Treatment | Changes in HR |

|---|---|

| Saline+saline (n=6) | 22±16 |

| Saline+pilocarpine (n=4) | 51±21 |

| Pirenzepine+pilocarpine (n=4) | 46±10 |

| Saline+pilocarpine (n=4) | 51±30 |

| 4-DAMP+pilocarpine (n=4) | 45±41 |

| Saline+pilocarpine (n=5) | 56±14 |

| Methoctramine+pilocarpine (n=5) | 53±12 |

| Saline+pilocarpine (n=7) | 63±13 |

| Tropicamide+pilocarpine (n=7) | 34±18 |

Abbreviation: HR, heart rate.

The results are presented as means±s.e.mean.

Doses: pilocarpine (4 μmol per kg body weight), pirenzepine (100 nmol), 4-DAMP (50 nmol), methoctramine (50 nmol) and tropicamide (500 nmol). n=number of rats.

Treatment with pirenzepine (100 nmol) (F(6, 25)=8.76; P<0.001) (Figure 3a) or 4-DAMP (25 and 50 nmol) (F(6, 31)=29.33; P<0.001) (Figure 3b) injected intracerebroventricularly reduced i.v. pilocarpine-induced pressor responses.

Pirenzepine (25 and 50 nmol), 4-DAMP (10 nmol), methoctramine (25 and 50 nmol) and tropicamide (500 nmol) injected intracerebroventricularly did not alter i.v. pilocarpine-induced pressor responses (Figure 3).

The hypotensive responses induced by i.v. pilocarpine were not altered by the pretreatment, i.c.v., with pirenzepine (25, 50 and 100 nmol), methoctramine (25 and 50 nmol), 4-DAMP (10, 25 and 50 nmol) or tropicamide (500 nmol) (Figure 3).

Pilocarpine (i.v.) produced no change in HR in the rats pretreated with an i.c.v. injection of saline, pirenzepine (100 nmol), methoctramine (50 nmol), 4-DAMP (50 nmol) or tropicamide (500 nmol) (F(8, 37)=1.63; P>0.05) (Table 2).

Discussion and conclusions

As shown by the present and previous studies (Gay et al., 1976; Fregly et al., 1982; Iwabuchi et al., 1994; Moreira et al., 2003; Rowland et al., 2003; Takakura et al., 2003, 2005), peripherally injected pilocarpine in rats induces salivation, water intake and a transitory (less than 1 min) depressor response followed by a long-lasting (around 1 h) pressor response. The present results show that salivation induced by i.p. pilocarpine was strongly reduced by an i.c.v. injection of the M1/M3 antagonist 4-DAMP, whereas the other antagonists did not affect pilocarpine-induced salivation. Water intake and pressor responses to peripheral pilocarpine were reduced by i.c.v. injections of pirenzepine or 4-DAMP (M1 and M1/M3 antagonists, respectively). The M2/M4 antagonist metoctramine i.c.v. reduced pilocarpine-induced water intake and also sodium depletion-induced sodium intake, which suggests that methoctramine may have a nonspecific inhibitory effect on ingestive behaviours. Tropicamide (M4 antagonist) did not affect salivation, water intake or pressor responses. Pilocarpine-induced hypotension was not affected by central injections of muscarinic antagonists at doses that affected pressor responses, salivation or water intake. The results suggest that part of the salivation produced by pilocarpine injected peripherally depends on the activation of central M3 receptors, whereas central M1 receptors are involved on peripheral pilocarpine-induced water intake and pressor responses. As 4-DAMP is both M1 and M3 antagonists, it is not possible to exclude the involvement of central M3 receptors in pilocarpine-induced water intake and pressor responses.

It is well known that the activation of M3 receptors directly in salivary glands produces salivation (Iwabuchi et al., 1994; Nakamura et al., 2004; Sato et al., 2006, Proctor, 2006; Tobin et al., 2006). However, pilocarpine administered systemically may cross the blood–brain barrier (Freedman et al., 1989) and, acting centrally, facilitate salivation as suggested by the reduction of i.p. pilocarpine-induced salivation in rats with lesions in the AV3V region, lateral hypothalamus or medial preoptic area (Renzi et al., 1993, 2002; Lopes de Almeida et al., 2006). Pilocarpine injected centrally also produces salivation and atropine methyl bromide injected intracerebroventricularly at doses that act only centrally strongly reduces i.p. pilocarpine-induced salivation (Renzi et al., 1993; Takakura et al., 2003). The present results show that central injections of the M1/M3 receptor antagonist 4-DAMP reduce salivation induced by i.p. pilocarpine, whereas injections of the other specific muscarinic antagonists centrally produce no effect on salivation, suggesting the involvement of central M3 receptors on i.p. pilocarpine-induced salivation.

Central or peripheral injections of pilocarpine produce pressor responses (Sanchez and Méier, 1993; Moreira et al., 2003; Takakura et al., 2005). Electrolytic lesions of the AV3V region abolish i.p. pilocarpine-induced pressor responses and mesenteric vasoconstriction, suggesting that i.p. pilocarpine activates central pressor mechanisms dependent on the AV3V region to produce pressor responses (Takakura et al., 2005). The results of this study show that i.v. pilocarpine-induced pressor responses are reduced by the previous treatment with 4-DAMP (25 and 50 nmol) and pirenzepine (100 nmol) injected i.c.v., suggesting that i.v. pilocarpine activates central M1 receptors and perhaps M3 receptors to increase arterial pressure. Although peripheral injection of pilocarpine simultaneously activates both central and peripheral opposite mechanisms, the pressor response suggests a predominance of central effects. However, after blockade of the central pressor mechanisms by AV3V lesions, i.p. pilocarpine induces vasodilatation and hypotension as a consequence of the predominant activation of peripheral mechanisms (Takakura et al., 2005). In this study, the blockade of central muscarinic receptors abolished the pressor responses to i.v. pilocarpine without changing hypotension. Probably, the antagonists at the doses used did not completely block the central pressor mechanisms, that is, the central mechanisms were still acting partially after i.c.v. injections of the antagonists, counterbalancing the peripheral effects.

Previous studies suggested the involvement of central M1 and M3 receptors in the dipsogenic responses to bethanechol and carbachol (muscarinic agonists) injected intracerebroventricularly (Massi et al., 1989; Polidori et al., 1990; Rowland et al., 2003). In this study, pilocarpine-induced water intake was blocked by the treatment with the M1 antagonist (pirenzepine) injected i.c.v. in a very low dose (0.1 nmol) or the M1/M3 antagonist 4-DAMP (5 and 10 nmol) i.c.v., but not by tropicamide. The same doses of pirenzepine or 4-DAMP that reduced the dipsogenic response to i.p. pilocarpine produced no effect on 24 h sodium depletion-induced 0.3 M NaCl intake, which suggests that the effects of these drugs are not due to nonspecific inhibition of ingestive behaviours. However, the M2/M4 antagonist methoctramine may have a nonspecific inhibitory effect on ingestive behaviours because it reduced pilocarpine-induced water intake and also sodium depletion-induced sodium intake. Therefore, pilocarpine activates central M1 receptors and perhaps M3 receptors to induce water intake.

Although previous studies have suggested the involvement of peripheral mechanisms on the dipsogenic response to peripheral pilocarpine (Gay et al., 1976; Fregly et al., 1982; Rowland et al., 2003), the present results suggest that this response is totally dependent on the activation of central M1 receptors and perhaps M3 receptors. Therefore, the effects of peripherally administered pilocarpine are totally dependent on its central action (water intake) or a mix of central and peripheral actions (salivation and cardiovascular responses). By acting centrally or peripherally, pilocarpine produces the same effect on salivary secretion and the total of salivation is probably the result of the two mechanisms acting together, whereas the cardiovascular effects are opposite. That is, by acting peripherally, pilocarpine induces hypotension, whereas acting centrally it induces hypertension (Moreira et al., 2003; Takakura et al., 2005). The central pressor response opposing or counterbalancing the peripherally induced hypotension is likely to be essential for the maintenance of arterial pressure at a level needed to provide salivary gland blood flow appropriate for salivation.

The effective doses of each muscarinic antagonist injected intracerebroventricularly were different for each response tested. Pirenzepine at very small dose (0.1 nmol) almost abolished pilocarpine-induced water intake. However, pirenzepine reduced pilocarpine-induced pressor response only at the dose of 100 nmol, suggesting that central M1 receptors activated by peripheral pilocarpine to produce dipsogenic responses are not the same as those involved in pressor responses and that they may be located in different central areas. Small doses of pirenzepine may block M1 receptors localized more periventricularly or more specifically in circumventricular organs, such as the subfornical organ, an area suggested to be activated by pilocarpine to induce water intake in a previous study (Sato et al., 2006). High doses of pirenzepine are needed to reach areas that are not periventricular, that is, areas that are deeper in the central neural parenchyma and that are activated by pilocarpine to produce pressor responses. The pretreatment with 4-DAMP intracerebroventricularly reduced or almost abolished all the responses tested; however, similar to pirenzepine, the effective doses for each response were not the same. Again, a small dose of 4-DAMP (5 nmol) reduced pilocarpine-induced water intake, whereas the 25 nmol dose of 4-DAMP reduced pilocarpine-induced salivation and pressor responses. Similar to pirenzepine, small doses of 4-DAMP may block M1 and/or M3 receptors located periventricularly that are involved in the dipsogenic response and high doses are needed to block M1 and/or M3 receptors involved in pilocarpine-induced salivation and pressor responses that are located far from the ventricles. A previous study (Sato et al., 2006) also showed that a small dose of i.c.v. atropine is effective at blocking i.p. pilocarpine-induced water intake, but does not alter i.p. pilocarpine-induced salivation. Moreover, the same study also showed that small doses of i.c.v. pilocarpine induce water intake, but not salivation, again suggesting that receptors activated to produce water intake are easily reached through i.c.v. injections compared with the receptors involved with salivation. Therefore, the present results testing specific muscarinic receptor subtypes and a previous study using i.c.v. injections of the nonspecific muscarinic antagonist atropine or even pilocarpine have shown similar effects, suggesting that muscarinic receptors activated by pilocarpine to produce water intake are not the same as those activated to induce salivation (or the pressor response according to the present results) and they are most likely located in different central areas.

In summary, the results suggest that salivation induced by i.p. pilocarpine depends on the activation of central M3 receptors, whereas water intake and pressor responses depend on central M1 receptor activation. The involvement of M3 receptors in water intake and pressor responses is not clear because 4-DAMP, that reduced these responses, blocks both M1 and M3 receptors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Silas Pereira Barbosa, Reginaldo da Conceição Queiroz and Silvia Fóglia for expert technical assistance, Silvana AD Malavolta for secretarial assistance and Ana V de Oliveira for animal care. This study was supported by public funding from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) and Conselho Nacional de Pesquisa (CNPq).

Abbreviations

- AV3V

anteroventral third ventricle

- HR

heart rate

- LV

lateral ventricle

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Aslan N, Goren Z, Onat F, Oktay S. Carbachol-induced pressor responses and muscarinic M1 receptors in the central nucleus of amydala in conscious rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;333:63–67. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01106-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brann MR, Ellis J, Jorgensen H, Hill-Eubanks D, Jones SV. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes: localization and structure/function. Prog Brain Res. 1993;98:121–127. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)62388-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton J, Martinez JR, Martinez AM, Young JA. Fluid and electrolyte secretion from the isolated, perfused submandibular and sublingual glands of the rat. Arch Oral Biol. 1981;26:555–561. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(81)90017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson MM. Pilocarpine and other cholinergic drugs in the management of salivary gland dysfunction. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1993;75:186–191. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(93)90092-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher AE, Coury JN. Chemical tracing of a central neural circuit underlying the thirst drive. Science. 1962;138:691–693. doi: 10.1126/science.138.3541.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox RI, Konttinen Y, Fisher A. Use of muscarinic agonists in the treatment of Sjogren's syndrome. Clin Immunol. 2001;101:249–263. doi: 10.1006/clim.2001.5128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman SB, Harley EA, Pastel S. Direct measurement of muscarinic agents in the central nervous system of mice using ex vivo biding. Eur J Pharmacol. 1989;175:253–260. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90317-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fregly MJ, Kikta DC, Greenleaf JE. Bethanechol-induced water intake in rats: possible mechanisms of induction. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1982;17:727–732. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(82)90354-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gay PE, Benner SC, Leaf RC. Drinking induced by parenteral injections of pilocarpine. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1976;5:633–638. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(76)90304-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giardina AR, Fisher AE. Effect of atropine on drinking induced by carbachol, angiotensin and isoproterenol. Physiol Behav. 1971;7:653–655. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(71)90123-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman SP. Eating or drinking elicited by direct adrenergic or cholinergic stimulation of the hypothalamus. Science. 1960;132:301–302. doi: 10.1126/science.132.3422.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwabuchi Y, Kataguri M, Masuhara T. Salivary secretion and histopathological effects after single administration of the muscarinic agonist Sin-2011 in MRL/Ipr mice. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1994;388:315–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt RA, Fisher AE. Anticholinergic blockade of centrally induced thirst. Science. 1966;154:520–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes de Almeida R, De Luca LA, Jr, Colombari DSA, Menani JV, Renzi A. Damage of the medial preoptic area impairs peripheral pilocarpine-induced salivary secretion. Brain Res. 2006;1085:144–148. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massi M, Polidori C, Melchiorre C. Methoctramine, a selective M2 muscarinic receptor antagonist, does not inhibit carbachol-induced drinking in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 1989;163:387–391. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90213-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayorga AJ, Cousins MS, Trevitt JT, Conlan A, Gianutsos G, Salamone JD. Characterization of the muscarinic receptor subtype mediating pilocarpine-induced tremulous jaw movements in rats. Brain Res. 1998;795:179–190. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00811-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menani JV, Saad WA, Camargo LAA, Renzi A, De Luca LA, Jr, Colombari E. The anteroventral third ventricle (AV3V) region is essential for pressor, dipsogenic and natriuretic responses to central carbachol. Neurosci Lett. 1990;133:339–344. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90608-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messer WS, Ellerbrock B, Jr, Price M, Hoss W. Autoradiographic analyses of agonist binding to muscarinic receptor subtypes. Biochem Pharmacol. 1989;38:837–850. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(89)90239-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira TS, Takakura ACT, Colombari E, De Luca LA, Jr, Renzi A, Menani JV. Central moxonidine on salivary glands blood flow and cardiovascular responses to pilocarpine. Brain Res. 2003;987:155–163. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03322-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Matsui M, Uchida K, Futatsugi A, Kusakawa S, Matsumoto N, et al. M(3) muscarinic acetylcholine receptor plays a critical role in parasympathetic control of salivation in mice. J Physiol. 2004;558:561–575. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.064626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelat M, Lazartigues E, Tran MA, Gharib C, Montrastruc JL, Montastruc P, et al. Characterization of the central muscarinic cholinoceptors involved in the cholinergic pressor response in anesthetized dogs. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;379:117–124. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00508-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polidori C, Massi M, Lambrecht G, Mutschler E, Tacke R, Melchiorre C. Selective antagonists provide evidence that M1 muscarinic receptors may mediate carbachol-induced drinking in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 1990;179:159–165. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)90413-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor GB. Muscarinic receptors and salivary secretion. J Appl Physiol. 2006;100:1103–1104. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01546.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renzi A, Colombari E, Mattos Filho TR, Silveira JEN, Saad WA, Camargo LAA, et al. Involvement of the central nervous system in the salivary secretion induced by pilocarpine in rats. J Dent Res. 1993;72:1481–1484. doi: 10.1177/00220345930720110401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renzi A, De Luca LA, Jr, Menani JV. Lesions of the lateral hypothalamus impair pilocarpine-induced salivation in rats. Brain Res Bull. 2002;58:455–459. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(02)00817-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland NE, Farnbauch LJ, Roberstson KL. Brain muscarinic receptor subytypes mediating water intake and Fos following cerebroventricular administration of bethanechol in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2003;167:174–179. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1394-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez C, Méier E. Central and peripheral mediation of hypothermia, tremor and salivation induced by muscarinic agonists in mice. Pharmacol Toxocol. 1993;72:262–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1993.tb01647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato N, Honda E, Haga K, Yokoto M, Inenaga K. Pilocarpine-induced salivation and thirst in conscious rats. J Dent Res. 2006;85:64–68. doi: 10.1177/154405910608500111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takakura ACT, Moreira TS, De Luca LA, Jr, Renzi A, Menani JV, Colombari E. Effects of AV3V lesion on pilocarpine-induced pressor response and salivary gland vasodilation. Brain Res. 2005;1055:111–121. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.06.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takakura ACT, Moreira TS, Laitano SC, De Luca LA, Jr, Renzi A. Central muscarinic receptors on pilocarpine-induced salivation. J Dental Res. 2003;82:993–997. doi: 10.1177/154405910308201211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tice MAB, Hashemi T, Taylor LA, McQuade RD. Distribution of muscarinic receptor subtypes in rat brain from postnatal to old age. Dev Brain Res. 1996;92:70–76. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(95)01515-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobin G, Ryberg AT, Gentle S, Edwards AV. Distribution and function of muscarinic receptor subtypes in the ovine submandibular gland. J Appl Physiol. 2006;100:1215–1223. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00779.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman LR, Faulds D. Oral pilocarpine: a review of its pharmacological properties and clinical potential in xerostomia. Drugs. 1995;49:143–155. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199549010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubieta JK, Frey KA. Autoradiographic mapping of M3 muscarinic receptors in the rat brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;264:415–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]