Abstract

Background and purpose:

The renal artery (RA) has been extensively investigated for the assessment of renal vascular function/dysfunction; however, few studies have focused on the intrarenal vasculature.

Experimental approach:

We devised a microvascular force measurement system, which allowed us to measure contractions of interlobar arteries (ILA), isolated from within the mouse kidney and prepared without endothelium.

Key results:

KCl (50 mM) induced similar force development in the aorta and RA but responses in the ILA were about 50% lower. Treatment of RA with 10 μM phenylephrine (PE), 10 nM U46619 (thromboxane A2 analogue) or 10 μM prostaglandin F2α elicited a response greater than 150% of that induced by KCl. In ILA, 10 nM U46619 elicited a response that was 130% of the KCl-induced response; however, other agonists induced levels similar to that induced by KCl. High glucose conditions (22.2 mM glucose) significantly enhanced responses in RA and ILA to PE or U46619 stimulation. This enhancement was suppressed by rottlerin, a calcium-independent PKC inhibitor, indicating that glucose-dependent, enhanced small vessel contractility in the kidney was linked to the activation of calcium-independent PKC.

Conclusion and implications:

Extra- and intrarenal arteries exhibit different profiles of agonist-induced contractions. In ILA, only U46619 enhanced small vessel contractility in the kidney, which might lead to renal dysfunction and nephropathy through reduced intrarenal blood flow rate. A model has been established, which will allow the assessment of contractile responses of intrarenal arteries from murine models of renal disease, including type 2 diabetes.

Keywords: diabetic complications, nephrology, intra-renal vasculature, vascular smooth muscle, contraction, PKC, thromboxane A2

Introduction

Alterations in renal vascular function, notably in the intrarenal arteries, are a major contributing factor to renal dysfunction (Wang et al., 1999; Kamata et al., 2006). Furthermore, the increase in diabetes, particularly type 2 diabetes, is associated with an increase in nephropathy as a major complication. In general, early-stage nephropathy patients exhibit microalbuminuria, which can be detected in the absence of an increase in total protein excretion. During this stage, pathological examination reveals slight diffusion and/or nodulation of mesangial cells (Riser et al., 2000). Typically, when the nephropathy is characterized by a proteinuria of 300 mg day−1, intrarenal microvascular tissue in excess of 50% has been damaged (Gaede, 2006). These dysfunctions of vascular smooth muscle and/or endothelial cells reduce renal haemofiltration (Kanie and Kamata, 2000). Extracellular glucose is believed to be an important factor in modulating renal vascular function. Elevation of extracellular glucose, as in diabetes, induces dysfunction of microvascular tissues (Taneda et al., 2003; Scalia et al., 2007). Persistent glucose accumulation leads to chronic renal dysfunction, which ultimately requires renal replacement therapy (Rutkowski et al., 2006).

Measurement of force development is a common experimental approach used to assess vascular function; however, this technique is technically difficult with respect to the intrarenal vasculature. The renal artery (RA) has frequently been examined as a surrogate tissue in which to measure renal vascular function; however, the RA is an extrarenal vessel located between the abdominal artery and the kidney (Fink, 1997; Watts and Thompson, 2004). Alterations of the contractile properties of the RA have been reported in spontaneous hypertensive rats (Hoshino et al., 1994) and diabetic mice (Rodriguez et al., 2006), but such changes may not reflect alterations in intrarenal vascular function. Apart from studies of the RA, renal function has also been evaluated using cultured renal vascular cells (Jiang et al., 2004), measurement of whole kidney flow rate (Patzak et al., 2004) and examination of renal microvasculature function in the hydronephrotic rodent kidney (Wang and Loutzenhiser, 2002). Unfortunately, such studies do not afford direct measurement of vascular contraction. Thus, it was necessary to develop force measurement techniques that can be applied to isolated intrarenal microvessels. Force measurement in intrarenal arteries has previously been documented for both the dog (Discigil et al., 2004) and the rabbit (Caffrey et al., 1990). In these investigations, the interlobar artery (ILA) was used as a typical intrarenal artery. However, experimental models of type 2 diabetes are difficult to establish in these species. The measurement of intrarenal vascular contraction in tissues isolated from mice would provide a basis for future studies with the widely available mouse models of type 2 diabetes (Nobe et al., 2004; Hsueh et al., 2007).

We have previously employed microvascular force techniques to measure the contractility of first- and second-order mouse mesenteric arteries (Nobe et al., 2006a). In these studies, we have applied similar techniques to evaluate contractile function in the mouse ILA. Endothelial cell-denuded vascular rings were used to assess responses of the smooth muscle of intrarenal vessels. The objectives of this investigation were to identify contractile responses in the ILA and to compare them with responses obtained in the RA and aorta, from the same ddY strain of mice. The effects of extracellular glucose on the contractile responses of these blood vessels were examined using concentrations of glucose comparable with the levels obtained in mouse models of diabetes. Finally, the involvement of PKC in these responses was investigated using inhibitors of calcium-dependent (Go6976) and calcium-independent (rottlerin) PKC isoforms.

Methods

Animals and tissue preparation

All animal procedures were carried out according to the Principles of Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the Japanese Pharmacological Society. Male ddY mice were purchased from Saitama Experimental Animals (Saitama, Japan) at 5–8 weeks of age (body weight, 20–25 g). Mice were housed at constant room temperature (20±2 °C) with 12-h light and dark cycles. Mice were fed with standard mouse chow, which included 5% fat (Oriental Yeast Corp., Tokyo, Japan). Food and water were available ad libitum and mice grew satisfactorily. At 8 weeks of age, animals were used for experiments. Mice were killed with ether. Vascular tissue components, which included abdominal aorta (aorta), RA and ILA, were isolated. The ILA is buried within the renal parenchyma and was isolated from connective tissue and renal parenchyma by dissection under a stereoscopic microscope. Lengths of isolated RA and ILA were 1.5–1.7 mm and 1.0–1.2 mm, respectively; internal diameters were 0.2–0.3 mm and 0.1–0.2 mm, respectively. The length of each tissue (at least 1 mm) was confirmed with a micrometre. Tissues were rinsed in ice-cold bicarbonate-buffered physiological salt solution (PSS). PSS consisted of (mM): 137 NaCl, 4.73 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4, 0.025 EDTA, 1.2 KH2PO4, 2.5 CaCl2 and 11.1 glucose (buffering was achieved with 25.0 mM NaHCO3; pH was 7.4 when the solution was bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 at 37 °C).

Endothelium-denuded blood vessels were used in all experiments. The endothelium was removed by rotating the vascular rings around stainless wires. The absence of acetylcholine-mediated vascular relaxation was confirmed before force measurements (data not shown).

Isometric force measurement

Isometric force measurement was conducted as described previously (Nobe et al., 2006a). Briefly, the vascular rings were mounted horizontally on the microvascular force measurement system. This system consisted of vascular ring holders (ultrathin stainless wires; 30 μm in diameter) attached to a high-sensitivity isometric force transducer (model-UL; Labo-Support, Osaka, Japan) and a 5 mL organ bath apparatus. Detected signals were converted to digital format through Power Lab instrumentation (AD Instruments, Tokyo, Japan). Tissues were pre-incubated in PSS for 30 min at 37 °C under each resting tension; earlier, various agents were applied. The high glucose condition was created by pretreatment of vascular tissue with HG-PSS (22.2 mM glucose in PSS) at 37 °C for 30 min as reported previously (Nobe et al., 2003c, 2006b).

Data analysis

Data are normalized in terms of identical length (1 mm) of vascular rings. Results are presented as typical experimental recordings and summarized as means±s.e.mean of 4–5 independent determinations. Statistical analyses for multiple comparisons were conducted with ANOVA for repeated measurements followed by the Student–Newman–Keuls test.

Reagents

Phenylephrine (PE) hydrochloride, 9,11-dideoxy-11α, 9α-epoxymethanoprostaglandin F2α (U46619), prostaglandin (PG)F2α and angiotensin II were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St Louis, MO, USA). Rottlerin (mallotoxin) was acquired from Calbiochem-Novabiochem (San Diego, CA). All other reagents, which were of the highest purity, were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. U46619 was dissolved in ethanol, whereas rottlerin was dissolved in dimethyl sulphoxide; no effects of vehicle were noted when total vehicle concentration was 0.03% or less.

Results

Basal force measurement of intra- and extrarenal vessels

Each vascular tissue was pre-incubated at resting tensions of 300, 400, 500 and 600 μN for 30 min, followed by 50 mM KCl, to establish an adequate resting tension for force measurement (Table 1). Under a resting tension of 300 μN, 50 mM KCl led to rapid and sustained increase in force development. Submaximal stimulation was evident 4–6 min after the addition of KCl; a subsequent rinse of the tissues returned the contractile force to its resting level. This force development pattern was common to aorta, RA and ILA.

Table 1.

Effect of basal resting tension on 50 mM KCl-induced response

| Tissue | n |

50 mM KCl response under each resting tension (μN mm−1) |

Repeatability (resting tension) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 300 μN | 400 μN | 500 μN | 600 μN | |||

| Aorta | 4 | 970.2±39.2 | 1156.4±50.5* | 1433.6±108.4* | 1457.7±118.6* | >5 times (600 μN) |

| RA | 4 | 1535.3±287.9 | 1698.7±323.4 | 1845.7±371.9 | 1532.2±323.6 | <2 times (500 μN) |

| ILA | 4 | 718.7±32.7 | 784.0±56.6* | 849.3±117.8* | 823.4±115.2* | < 3 times (500 μN) |

*P<0.05 vs responses under 300-μN resting tension.

Isolated aorta, RA and ILA were mounted on the force measurement system with indicated resting tensions. After 20- to 30-min incubation, 50 mM KCl was added at 37 °C for 10 min. Each maximal force level including resting tension was detected. Values are expressed as the mean±s.e.mean (n=4 for all groups). *P<0.05 from response under resting tension of 300 μN. Repeatability was assessed by stimulation (10 min) and rinse (30 min) cycles under identical resting tension. Over 90% of previous responses were counted.

In the aorta, elevation of the resting tension from 300 to 600 μN enhanced the response to 50 mM KCl. The response under a resting tension of 600 μN was submaximal in comparison with 800 and 1000 μN (data not shown). Under a resting tension of 600 μN, consistent KCl-induced responses (in excess of 90% of the first challenge) were obtained at 30 min intervals.

In the ILA, the KCl response was increased under a resting tension of 400 μN, which was not enhanced upon further elevation of the resting tension (>500 μN). At 500 μN resting tension, the response to KCl could only be reproduced 2–3 times. In the RA, similar KCl-induced responses were evident under a resting tension of 400 μN. At 500 μN resting tension, responses greater than 90% of the first KCl response could only be repeated twice. In all further experiments, a resting tension of 600 μN was employed for the aorta and a resting tension of 400 μN for the RA and ILA.

Agonist-induced responses in mouse RA and ILA

Agonist-induced force developments were compared between the mouse RA and ILA (Figure 1). PE, U46619 (thromboxane A2 analogue), PGF2α and angiotensin II all induced contractile responses, in both vascular tissues. In preliminary trials, the contraction induced by each agonist was submaximal, and the response to 50 mM KCl was employed as the positive control.

Figure 1.

Agonist-induced contractile responses in endothelial-denuded renal (RA) and interlobar (ILA) arterial rings. Isometric force development in RA (a) and ILA (b) was measured under resting tension of 400 μN. Upon detection of a maximal response to 50 mM KCl, each contractile agonist, 10 μM phenylephrine (PE); 100 nM U46619 (U46619); 10 μM PGF2α (PG); or 1 μM angiotensin II (Ang) was applied at 37 °C for 5 min and representative recordings shown. In (c), data are summarized, relative to responses to 50 mM KCl (% 50 mM KCl). Each value represents the mean±s.e.m. of five independent determinations. *P<0.01 from KCl-induced response; #P<0.01 from response in RA.

In the RA, the maximal responses obtained to 10 μM PE, 10 nM U46619 and 10 μM PGF2α were 1988±116, 2390±109 and 2284±111 μN mm−1 (n=5), respectively (Figure 1a). Force developments in the presence of PE, U46619 and PGF2α were significantly larger than those induced by 50 mM KCl (Figure 1c). However, only a transient increase in force development was induced by 1 μM angiotensin II (810±39 μN mm−1), which was markedly lower than that induced by KCl. Although responses to PE, U46619 and PGF2α could be repeated at 30 min intervals, the response to angiotensin II diminished in a manner dependent on the stimulation-rinse cycles (to less than 40% of the first challenge). Similar responses were obtained in the aorta where 10 μM PE, 100 nM U46619, 10 μM PGF2α and 1 μM angiotensin II induced responses of 1510±55, 3007±85, 2387±134 and 738±46 μN mm−1 (n=5), respectively.

In the ILA, maximal responses to 10 μM PE (680±25 μN mm−1; n=5) and 10 μM PGF2α (626±16 μN mm−1; n=5) were not significantly different from that induced by 50 mM KCl (662±25 μN mm−1; n=5) (Figure 1b). The response to 100 nM U46619 (734±40 μN mm−1; n=5) was, however, significantly higher (Figure 1c). Application of 1 μM angiotensin II to the ILA induced a transient increase in force development (573±36 μN mm−1; n=5), approaching the level induced by 50 mM KCl. U46619- and PGF2á-induced responses in ILA were significantly lower than the corresponding responses in RA. In contrast, the response to angiotensin II was lower in the RA (Figure 1c).

PE-induced force development in RA and ILA: effect of high glucose

Concentration–response curves to PE were obtained in endothelial-denuded rings from RA and ILA (Figure 2). The cumulative addition of PE led to substantial increases in isometric force. In the RA, the maximal response attained with 30 μM PE was 2003±95 μN mm−1 (n=5). In the ILA, a maximal increase in force development of 675±17 μN mm−1 (n=5) was also obtained with 30 μM PE. Concentration–response curves for PE were similar in the RA and ILA with pD2 values of 5.60 and 5.43, respectively. The α1 adrenoceptor antagonist, prazosin (1, 3 and 10 nM, 10 min pre-incubation), attenuated the PE-induced increase in isometric force in both RA and ILA. Dose–response curves were shifted to higher concentrations of PE, yielding a pA2 value for prazosin in the RA and ILA of 9.5 and 9.3, respectively.

Figure 2.

Phenylephrine (PE)-induced force development in endothelial-denuded renal (RA) and interlobar (ILA) arterial rings under normal and high glucose conditions. Representative recordings of force development in RA (a) and ILA (b) are presented. Concentration–response relationships for PE-induced isometric force responses in RA and ILA were calculated as % of the maximal response in normal physiological salt solution (PSS) (c). Vascular tissues were pre-incubated under normal and high glucose conditions at 37 °C for 30 min. Each value represents the mean±s.e.m. of five independent determinations. *P<0.01 vs responses in normal PSS.

Phenylephrine-induced force developments were measured after incubation with high-glucose PSS (HG-PSS; 22.2 μM glucose in PSS). Pretreatment of the RA with HG-PSS for 30 min did not alter the resting tension. However, the PE-induced, dose-dependent increase in force development was significantly enhanced over the concentration range, 0.3–3 μM (Figures 2a and c). RA force developments induced by 3 μM PE under normal and high-glucose conditions were 1271±67 and 1840±76 μN mm−1 (n=5), respectively. After treatment with HG-PSS, the pD2 value for PE in the RA increased to 6.11.

In ILA, the PE-induced increase in force development remained unaffected by the elevation of extracellular glucose (Figure 2b). The resting tension in HG-PSS was 401±7 μN mm−1 (n=5), which increased in the presence of 30 μM PE to 688±3 μN mm−1 (n=5). After treatment with HG-PSS, the pD2 value for PE remained unchanged at 5.40 (Figure 2c). Contraction of the ILA was not influenced by either a further increase in the glucose concentration (to >33 mM) or by extending the incubation time.

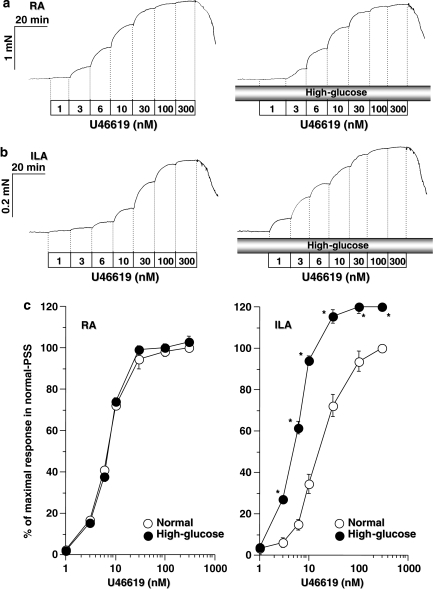

U46619-induced force development in RA and ILA: effect of high glucose

Cumulative treatment of RA and ILA with U46619 induced dose-dependent increases in force development (left panels of Figures 3a and b). Maximal responses to U46619 (2422±19 and 746±8 mN mm−1, n=5) in RA and ILA, respectively, were slightly higher than those detected following PE. Under normal conditions, the pD2 values in RA and ILA were 8.16 and 7.99, respectively. The thromboxane A2 (TXA2) receptor antagonist, ([1S-[1α,2 α (Z),3 α,4 α]]-7-[3-[[2-(phenylamino)carbonyl] hydrazino]methyl]-7-oxabicyclo[2.2.1]hept-2-yl)-5-heptenoic acid) (10, 30 and 100 nM, 10 min pre-incubation), reduced the increase in isometric force induced by U46619 in RA and ILA. Concentration–response curves were shifted to higher concentrations of U46619, with pA2 values for ([1S-[1α,2 α (Z),3 α, 4 α]]-7-[3-[[2-(phenylamino)carbonyl] hydrazino]methyl]-7-oxabicyclo[2.2.1]hept-2-yl)-5-heptenoic acid) in mouse RA and ILA of 8.6 and 8.5, respectively.

Figure 3.

U46619-induced force development in endothelial-denuded renal (RA) and interlobar (ILA) arterial rings under normal and high glucose conditions. Representative recordings of force development in RA (a) and ILA (b) are presented. Concentration–response relationships for U46619-induced isometric force responses in RA and ILA were indicated as % of the maximal response in normal physiological salt solution (PSS) (c). Vascular tissues were pre-incubated under normal and high glucose conditions at 37 °C for 30 min. Each value represents the mean±s.e.mean of five independent determinations. *P<0.01 vs responses in normal PSS.

Under high glucose conditions, the U46619-induced increase in force development was significantly enhanced in ILA; in contrast, high glucose treatment did not alter the response in RA (right panels of Figure 3a and b). Significant enhancement in ILA was observed following application of U46619 at concentrations exceeding 3 nM, with maximal responses at 300 nM U46619 of 824±14 μN mm−1 (n=5) and a pD2 value of 8.20.

Effect of PKC inhibitor on RA and ILA force responses

The concentration of agonist most responsive to an increase in extracellular glucose was 3 μM for PE and 10 nM for U46619 (see Figures 2c and 3c). We have documented previously the involvement of the calcium-independent PKC isoform in vascular responses dependent on extracellular glucose.

Rottlerin is an inhibitor of the calcium-independent PKC isoforms including PKC-δ (Woolfolk et al., 2005; Sedmikova et al., 2006). In the RA, the enhancement of force development induced by 3 μM PE remained unaffected by 1 μM rottlerin (Figure 4a). However, enhancement of the PE-induced response under high glucose conditions was totally suppressed. In contrast, responses to 10 nM U46619 remained unaffected by rottlerin under either normal or high glucose conditions.

Figure 4.

Effect of rottlerin (1 μM), a calcium-independent PKC inhibitor, on the increase in agonist-induced force development stimulated by high glucose conditions in endothelium-denuded renal (RA) (a) and interlobar (ILA) (b) arterial rings. Isolated vascular tissues were pre-incubated under normal and high glucose conditions and stimulated with either 3 μM phenylephrine (PE) or 10 nM U46619. Rottlerin (1 μM) was added 10 min before agonist stimulation. *P<0.01 vs unstimulated resting level; #P<0.01 vs responses in normal physiological salt solution (PSS).

In ILA, pretreatment with 1 μM rottlerin did not influence the 3 μM PE-induced increase in force development in either normal or high glucose conditions. However, the enhanced response to 10 nM U46619 in high glucose conditions was suppressed in the presence of 1 μM rottlerin. Rottlerin only inhibited the glucose-dependent enhancement in force development in both the RA and ILA.

We also assessed the effects of an inhibitor of calcium-dependent PKC isoforms, Gö6976 (Martiny-Baron et al., 1993; Yang et al., 2001). Pretreatment of RA with 1 μM Gö6976 reduced both PE- and U4619-induced force developments (919±53 and 1493±80 μN mm−1; n=5, respectively). A similar inhibitory effect was observed with both agonists, but the inhibition was not influenced by high glucose conditions. In ILA, PE- and U46619-induced force developments were reduced to 503±15 and 497±13 μN mm−1 (n=5), respectively, and neither response was affected by high glucose. Thus, in the presence of Gö6976, neither agonist-specific inhibition nor glucose-dependent inhibition was observed in either tissue.

Discussion

This investigation established different profiles of agonist-induced contractions in the mouse RA and ILA. We previously developed a microvascular force measurement system for the detection of contractile responses in low-resistance murine arteries (Nobe et al., 2006a). On the basis of several preliminary trials, the smallest mouse ILA capable of mounting on a force measurement apparatus was selected. The ILA we have used, located within the second branch of the RA, is believed to be a typical intrarenal artery. Alterations of microvasculature in the renal glomerulus are thought to be involved in renal hypertension; however, an association between the ILA and hypertensive atherosclerosis and hypertension has also been reported (Jensen et al., 1994). Responses in the ILA have been studied previously in dogs and rabbits (Caffrey et al., 1990; Discigil et al., 2004), but not in mice. To measure force development in the ILA, the sensitivity of the force transducer was increased as the tissue-mounting wires were minimized (30 μm in diameter, 1.0–1.3 mm in length). These improvements facilitated the detection of agonist-induced force development in mouse ILA. Detected force responses are indicated as ‘developed force level per 1 mm of vascular tissue length (μN mm−1)' (Guan et al., 2006). Application of basal resting tension to vascular rings was also assessed given that vascular force development is influenced by the resting tension. Our measurements revealed optimal resting tension levels of 600 μN for aorta and 400 μN for both RA and ILA. KCl (50 mM)-induced force development under the resting tension was similar to that reported previously (Carr et al., 2001; Je and Sohn, 2007) and preliminary trials indicated that stable vascular responses were maintained for 8–12 h under these conditions.

Following treatment of RA with vascular contractile agonists, sustained force developments significantly larger than that induced by 50 mM KCl were measured in response to PE, U46619 and PGF2α. The aorta exhibited responses similar to those of RA. In ILA, significant differences in maximal contraction relative to the 50 mM KCl response were apparent only after stimulation with U46619. PE- and PGF2α-induced maximal responses, similar to that induced by 50 mM KCl. Therefore, these data suggested that agonist sensitivities differed between intra- and extrarenal vessels. Angiotensin II, an important regulator of kidney blood flow, demonstrates differential action in the renal microvasculature (Patzak and Persson, 2007). Angiotensin II induced small, transient contractions in RA and ILA as reported for other tissues (Yu et al., 2004). The greater response to angiotensin II, evident in the mouse ILA, suggested a degree of hypersensitivity within the intrarenal vessel. This investigation is the first to describe contractions of mouse intrarenal artery, induced by multiple agonists. To assess RA dysfunction, intrarenal arteries should be subjected to force measurement, and the experimental system established in this study could be employed to examine vessels obtained from mice with experimental forms of renal disease.

To document the contractile characteristics of RA and ILA, two major vascular contractile agonists were introduced. PE- and U46619-induced contractions were evaluated in terms of different agonist sensitivities between ILA and RA. Both PE and U46619 caused dose-dependent contractions in RA and ILA. Dose–response curves revealed similar PE-induced responses in RA and ILA; however, U46619-induced responses differed. Therefore, these results suggested that ILA exhibits low contractility to U46619 in comparison with RA. Participation of the inflammatory factor, TXA2, has been noted in diabetic nephropathy (Wardle, 1996). In addition, TXA2 reportedly induced proteinuria in a nephropathy model (Stahl et al., 1992).

Diabetic nephropathy is triggered by increases in extracellular glucose levels (Taneda et al., 2003); consequently, we examined these contractions of renal vessels under high glucose conditions (Nobe et al., 2003b, 2004). Enhancement of PE-induced contractions by high extracellular glucose was observed only in RA. In the presence of U46619, the contractile response of the RA in HG-PSS was not significantly different from the response in normal PSS. In contrast, responses in the ILA to U46619 were significantly enhanced by high glucose conditions. These data provide the first evidence of a potentially important selective effect of high glucose and pro-inflammatory stimuli on the intrarenal vasculature. Diabetic nephropathy is a consequence of hyperglycaemia (Lee et al., 2005). Furthermore, elevated TXA2 levels in kidney lead to proteinuria (Okumura et al., 2003). Increases in TXA2 in kidney under high glucose conditions might induce enhanced contractility of intrarenal artery. This increase in contractility could potentially exacerbate diabetic nephropathy. Enhanced contraction of the RA was detected only during activation with PE, suggesting that contraction of the RA, mediated by sympathetic nerves, could be elevated under hyperglycemic conditions (Figure 5b); however, contractile responses to PE in the ILA were unaltered. Under high glucose conditions, blood flow from the aorta to the kidney would be reduced. On the other hand, an increase in TXA2 and blood glucose levels would result in greater constriction of the ILA without affecting renal blood flow through the RA (Figure 5d). Thus, intrarenal blood flow would decline, which, with maintained extrarenal blood flow, would increase blood pressure within the renal tissue with resultant renal damage. Under conditions of diabetic hyperglycaemia, an increase in TXA2 increases proteinuria (Wolf and Ziyadeh, 2007). Consequently, we suggest that glucose-dependent enhanced contractility of the ILA could have an important function in diabetic nephropathy.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagrams illustrating responses of intra- and extrarenal vessels under normal and high glucose conditions. (a, b) Phenylephrine (PE)- and (c, d) U46619-induced contractile responses in RA and ILA under normal (a, c) and high glucose (HG) (b, d) conditions are illustrated.

What mechanism governs enhanced contractility of ILA and RA under high glucose conditions? In some vascular tissues, glucose taken up by the cell under high glucose conditions is utilized in the glycolytic and in the de novo synthesis pathways (Ramana et al., 2005). Glucose is converted to lipid diacyglycerols, which enhance vascular contraction through the activation of PKC. Conversion steps from glucose to diacyglycerols have been reported (Williamson et al., 1993). Diacyglycerols derived from glucose contain distinct acyl chains. Previous publications have suggested that this non-standard diacyglycerol species activates the calcium-independent isoform of PKC (Szule et al., 2002; Das Evcimen and King, 2007). Consequently, the effect of a calcium-independent PKC inhibitor (rottlerin) (Kontny et al., 2000) on glucose-dependent enhancement of RA and ILA contraction was examined (Figure 4). Enhanced contractility in both RA and ILA under high glucose conditions diminished significantly following pretreatment with rottlerin. These results suggested the involvement of calcium-independent PKC in the enhanced contractility of RA and ILA, probably through the formation of non-standard diacyglycerols from the high extracellular glucose. Rottlerin displays selectivity for the PKC-ä isoform in some types of cells (Kontny et al., 2000); however, negative evidence was also documented (Davies et al., 2000). Therefore, the isoform of calcium-independent PKC associated with ILA contraction could not be identified in this study. Some groups reported that calcium-dependent PKC (PKC-β) is activated under high glucose conditions or in diabetes in other types of cells (Hayashida and Schnaper, 2004; Avignon and Sultan, 2006). However, in our model, an inhibitor of this calcium-dependent PKC isoform, Gö6976 (Martiny-Baron et al., 1993), did not affect enhanced contractility. Thus, our results suggested that the high glucose potentiation (and subsequent intrarenal vascular dysfunction) was mediated by an alteration of calcium-independent PKC activity, which might derive from renal-specific characteristics. This study demonstrated that the effects of high extracellular glucose on intrarenal arteries only affected agonist action at the TXA2 receptor. This stimulation coupled with the non-standard diacyglycerol–PKC pathway and alteration of this pathway might be related to enhanced contractility of intrarenal arteries under high glucose conditions. Our present data regarding enhancement of contractile sensitivity in ILA under high glucose conditions, in concert with previous results indicating that the formation of TXA2 in kidney leads to development of diabetic nephropathy, are of critical importance to a thorough understanding of the mechanisms underlying nephropathy.

This investigation is the first to compare and identify distinct profiles of the agonist-induced contractions in the mouse RA and ILA. We reported that elevated glucose differentially affects agonist-induced responsiveness in these vessels, with high glucose selectively enhancing α-adrenoceptor-mediated contraction in the RA, whereas in the ILA, it was the TxA2 receptor-mediated contraction that was potentiated. These data further suggested that formation of TXA2 in the kidney under high glucose conditions contributes to diabetic nephropathy through intrarenal artery dysfunction. On the basis of the correlation between enhanced vascular contractility and atypical diacyglycerol–PKC pathway activation, we concluded that normalization of renal vascular contraction and/or the diacyglycerol–PKC pathway should potentially reduce diabetic nephropathy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a Showa University Grant-in-Aid for Innovative Collaborative Research Projects and a Special Research Grant-in- Aid for Development of Characteristic Education from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture Sports, Science and Technology (KN, TH and HK).

Abbreviations

- ILA

interlobar artery

- PG

prostaglandin

- PSS

physiological salt solution

- RA

renal artery

- TXA2

thromboxane A2

- U46619

9,11-dideoxy-11α, 9α-epoxymethanoprostaglandin F2α

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Avignon A, Sultan A. PKC-B inhibition: a new therapeutic approach for diabetic complications. Diabetes Metab. 2006;32:205–213. doi: 10.1016/s1262-3636(07)70270-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffrey JL, Hathorne LF, Carter GC, Sinclair RJ. Naloxone potentiates contractile responses to epinephrine in isolated canine arteries. Circ Shock. 1990;31:317–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr AN, Sutliff RL, Weber CS, Allen PB, Greengard P, de Lanerolle P, et al. Is myosin phosphatase regulated in vivo by inhibitor-1? Evidence from inhibitor-1 knockout mice. J Physiol. 2001;534:357–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00357.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das Evcimen N, King GL. The role of protein kinase C activation and the vascular complications of diabetes. Pharmacol Res. 2007;55:498–510. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2007.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies SP, Reddy H, Caivano M, Cohen P. Specificity and mechanism of action of some commonly used protein kinase inhibitors. Biochem J. 2000;351:95–105. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3510095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Discigil B, Evora PR, Pearson PJ, Viaro F, Rodrigues AJ, Schaff HV. Ionic radiocontrast inhibits endothelium-dependent vasodilation of the canine renal artery in vitro: possible mechanism of renal failure following contrast medium infusion. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2004;37:259–265. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2004000200014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink GD. Long-term sympatho-excitatory effect of angiotensin II: a mechanism of spontaneous and renovascular hypertension. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1997;24:91–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1997.tb01789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaede PH. Intensified multifactorial intervention in patients with type 2 diabetes and microalbuminuria: rationale and effect on late-diabetic complications. Dan Med Bull. 2006;53:258–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan YY, Zhou JG, Zhang Z, Wang GL, Cai BX, Hong L, et al. Ginsenoside-Rd from panax notoginseng blocks Ca2+ influx through receptor- and store-operated Ca2+ channels in vascular smooth muscle cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;548:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashida T, Schnaper HW. High ambient glucose enhances sensitivity to TGF-beta1 via extracellular signal—regulated kinase and protein kinase Cdelta activities in human mesangial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:2032–2041. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000133198.74973.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshino J, Sakamaki T, Nakamura T, Kobayashi M, Kato M, Sakamoto H, et al. Exaggerated vascular response due to endothelial dysfunction and role of the renin-angiotensin system at early stage of renal hypertension in rats. Circ Res. 1994;74:130–138. doi: 10.1161/01.res.74.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsueh W, Abel ED, Breslow JL, Maeda N, Davis RC, Fisher EA, et al. Recipes for creating animal models of diabetic cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2007;100:1415–1427. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000266449.37396.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Je HD, Sohn UD. SM22alpha is required for agonist-induced regulation of contractility: evidence from SM22alpha knockout mice. Mol Cells. 2007;23:175–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen G, Bardelli M, Volkmann R, Caidahl K, Rose G, Aurell M. Renovascular resistance in primary hypertension: experimental variations detected by means of Doppler ultrasound. J Hypertens. 1994;12:959–964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang M, Mezentsev A, Kemp R, Byun K, Falck JR, Miano JM, et al. Smooth muscle—specific expression of CYP4A1 induces endothelial sprouting in renal arterial microvessels. Circ Res. 2004;94:167–174. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000111523.12842.FC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamata K, Hosokawa M, Matsumoto T, Kobayashi T. Altered arachidonic acid-mediated responses in the perfused kidney of the streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat. J Smooth Muscle Res. 2006;42:171–187. doi: 10.1540/jsmr.42.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanie N, Kamata K. Contractile responses in spontaneously diabetic mice. II. Effect of cholestyramine on enhanced contractile response of aorta to norepinephrine in C57BL/KsJ (db/db) mice. Gen Pharmacol. 2000;35:319–323. doi: 10.1016/s0306-3623(02)00116-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontny E, Kurowska M, Szczepanska K, Maslinski W. Rottlerin, a PKC isozyme-selective inhibitor, affects signaling events and cytokine production in human monocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;67:249–258. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Lee TW, Ihm CG, Kim MJ, Woo JT, Chung JH. Genetics of diabetic nephropathy in type 2 DM: candidate gene analysis for the pathogenic role of inflammation. Nephrology (Carlton) 2005;10 Suppl:S32–S36. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2005.00454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martiny-Baron G, Kazanietz MG, Mischak H, Blumberg PM, Kochs G, Hug H, et al. Selective inhibition of protein kinase C isozymes by the indolocarbazole Go 6976. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:9194–9197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobe K, Hagiwara C, Nezu Y, Honda K. Distinct agonist responsibilities of the first and second branches of mouse mesenteric artery. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2006a;47:422–427. doi: 10.1097/01.fjc.0000211702.72616.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobe K, Miyatake M, Sone T, Honda K. High-glucose-altered endothelial cell function involves both disruption of cell-to-cell connection and enhancement of force development. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006b;318:530–539. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.105015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobe K, Sakai Y, Nobe H, Takashima J, Paul RJ, Momose K. Enhancement effect under high-glucose conditions on U46619-induced spontaneous phasic contraction in mouse portal vein. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003b;304:1129–1142. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.040964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobe K, Suzuki H, Nobe H, Sakai Y, Momose K. High-glucose enhances a thromboxane A2-induced aortic contraction mediated by an alteration of phosphatidylinositol turnover. J Pharmacol Sci. 2003c;92:267–282. doi: 10.1254/jphs.92.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobe K, Suzuki H, Sakai Y, Nobe H, Paul RJ, Momose K. Glucose-dependent enhancement of spontaneous phasic contraction is suppressed in diabetic mouse portal vein: association with diacylglycerol-protein kinase C pathway. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;309:1263–1272. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.062802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okumura M, Imanishi M, Okamura M, Hosoi M, Okada N, Konishi Y, et al. Role for thromboxane A2 from glomerular thrombi in nephropathy with type 2 diabetic rats. Life Sci. 2003;72:2695–2705. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00180-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patzak A, Lai EY, Mrowka R, Steege A, Persson PB, Persson AE. AT1 receptors mediate angiotensin II-induced release of nitric oxide in afferent arterioles. Kidney Int. 2004;66:1949–1958. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patzak A, Persson AE. Angiotensin II-nitric oxide interaction in the kidney. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2007;16:46–51. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e328011a89b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramana KV, Friedrich B, Tammali R, West MB, Bhatnagar A, Srivastava SK. Requirement of aldose reductase for the hyperglycemic activation of protein kinase C and formation of diacylglycerol in vascular smooth muscle cells. Diabetes. 2005;54:818–829. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.3.818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riser BL, Denichilo M, Cortes P, Baker C, Grondin JM, Yee J, et al. Regulation of connective tissue growth factor activity in cultured rat mesangial cells and its expression in experimental diabetic glomerulosclerosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:25–38. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V11125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez WE, Tyagi N, Joshua IG, Passmore JC, Fleming JT, Falcone JC, et al. Pioglitazone mitigates renal glomerular vascular changes in high-fat, high-calorie-induced type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;291:F694–F701. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00398.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutkowski P, Klassen A, Sebekova K, Bahner U, Heidland A. Renal disease in obesity: the need for greater attention. J Ren Nutr. 2006;16:216–223. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scalia R, Gong Y, Berzins B, Zhao LJ, Sharma K. Hyperglycemia is a major determinant of albumin permeability in diabetic microcirculation: the role of mu-calpain. Diabetes. 2007;56:1842–1849. doi: 10.2337/db06-1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedmikova M, Rajmon R, Petr J, Svestkova D, Chmelikova E, Akal AB, et al. Effect of protein kinase C inhibitors on porcine oocyte activation. J Exp Zoolog A Comp Exp Biol. 2006;305:376–382. doi: 10.1002/jez.a.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl RA, Thaiss F, Wenzel U, Schoeppe W, Helmchen U. A rat model of progressive chronic glomerular sclerosis: the role of thromboxane inhibition. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1992;2:1568–1577. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V2111568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szule JA, Fuller NL, Rand RP. The effects of acyl chain length and saturation of diacylglycerols and phosphatidylcholines on membrane monolayer curvature. Biophys J. 2002;83:977–984. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(02)75223-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taneda S, Pippin JW, Sage EH, Hudkins KL, Takeuchi Y, Couser WG, et al. Amelioration of diabetic nephropathy in SPARC-null mice. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:968–980. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000054498.83125.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Iversen J, Strandgaard S. Contractility and endothelium-dependent relaxation of resistance vessels in polycystic kidney disease rats. J Vasc Res. 1999;36:502–509. doi: 10.1159/000025693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Loutzenhiser R. Determinants of renal microvascular response to ACh: afferent and efferent arteriolar actions of EDHF. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2002;282:F124–F132. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.0157.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardle EN. How does hyperglycaemia predispose to diabetic nephropathy. Qjm. 1996;89:943–951. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/89.12.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts SW, Thompson JM. Characterization of the contractile 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor in the renal artery of the normotensive rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;309:165–172. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.062562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson JR, Chang K, Frangos M, Hasan KS, Ido Y, Kawamura T, et al. Hyperglycemic pseudohypoxia and diabetic complications. Diabetes. 1993;42:801–813. doi: 10.2337/diab.42.6.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf G, Ziyadeh FN. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of proteinuria in diabetic nephropathy. Nephron Physiol. 2007;106:p26–p31. doi: 10.1159/000101797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolfolk EA, Eguchi S, Ohtsu H, Nakashima H, Ueno H, Gerthoffer WT, et al. Angiotensin II-induced activation of p21-activated kinase 1 requires Ca2+ Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;289:C1286–C1294. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00448.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang ZW, Wang J, Zheng T, Altura BT, Altura BM. Importance of PKC and PI3Ks in ethanol-induced contraction of cerebral arterial smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H2144–H2152. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.5.H2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Ogawa K, Tokinaga Y, Iwahashi S, Hatano Y. The vascular relaxing effects of sevoflurane and isoflurane are more important in hypertensive than in normotensive rats. Can J Anaesth. 2004;51:979–985. doi: 10.1007/BF03018483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]