Abstract

The Network for the Improvement of Addiction Treatment (NIATx) applies process improvement strategies to enhance the quality of care for the treatment of alcohol and drug disorders. A prior analysis reported significant reductions in days to treatment and significant increases in retention in care (McCarty et al., 2007). A second cohort of outpatient (n = 10) and intensive outpatient (n = 4) treatment centers tested the replicability of the NIATx model. An additional 20 months of data from the original cohort (7 outpatient, 4 intensive outpatient, and 4 residential treatment centers) assessed long-term sustainability. The replication analysis found a 38% reduction in days to treatment (30.7 days to 19.4 days) during an 18 month intervention. Retention in care improved 13% from the first to second session of care (from 75.4% to 85.0%), 12% between the first and third session of care (69.2% to 77.7%), and 18% between the first and fourth session of care (57.1% to 67.5%). The sustainability analysis suggested that treatment centers maintained the reductions in days to treatment and the enhanced retention in care. Replication of the NIATx improvements in a second cohort of treatment centers increases confidence in the application of process improvements to treatment for alcohol and drug disorders. The ability to sustain the gains after project awards were exhausted suggests that participating programs institutionalized the organizational changes that led to the enhanced performance.

Keywords: Quality Improvement, Retention in Care, Sustainability

1.0 Introduction

Manufacturers developed process improvement strategies to enhance customer satisfaction and product quality through reduction of product defects. Analysis of the production process identified causes of manufacturing errors and led to changes in process that eliminated or reduced sources of error and enhanced production efficiency. The net result was increased customer satisfaction, a decline in costs and increased revenue. Process improvement is expanding beyond manufacturing settings.

Health care systems, for example, are using multi-organizational improvement collaboratives to reduce morbidity and mortality rates and improve the quality of clinical care. The collaboratives engage like-minded corporations to improve processes within specific clinical or administrative areas (Wilson et al., 2003). Studies within large health care systems illuminate how change is implemented and sustained. Clinics within the British National Health Services were more likely to sustain change when a) strong leadership set a vision and linked change to strategic plans, b) the change team and leadership were focused, c) the change processes involved customers and staff, d) the change process had observable benefits, and e) communication was effective (Gollop et al., 2004; Ham et al., 2003). Similarly, the Veterans Administration implemented quality improvement most effectively when hospital leadership provided consistent vision and supported change (Parker et al., 1999), change was linked to a strategic plan (Nolan et al., 2005), and key customers and staff participated in the change process (Kirchner et al., 2004).

Health care systems have mixed records of sustaining change. Cardiothoracic surgeons (n = 23) in Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont, for example, collaborated to systematically improve quality of care and to reduce mortality following coronary artery bypass graft surgery; they achieved a 24% reduction in hospital mortality (O'Connor et al., 1996). The collaboration continued to refine practice and standardize care and reported in 2005 that mortality rates continued to decline and that institutional variations in mortality rates had been eliminated (Nugent, 2005). The Veterans Administration reduced wait times for primary care appointments from 60 days (fiscal year 2000) to 28 days (fiscal year 2002) and sustained the gains and made additional reductions to 25 days (fiscal 2004) (Nolan et al., 2005). Conversely, when 44 clinics with Ryan White funding participated in a series of learning sessions designed to promote breakthroughs in process improvements and enhanced quality of care for individuals with HIV infection, participation varied among clinics and patient outcomes did not improve (Landon et al., 2004). Application of process improvement to health care, therefore, appears to be a relatively complex process. Outcomes may vary overtime and interventions may not generalize to new medical concerns or to new clinical settings.

The Institute of Medicine’s Crossing the Quality Chasm reports call for widespread application of process improvement in the United States’ health care systems (Institute of Medicine, 2000; Institute of Medicine, 2001). They also recommend that this framework expand to address alcohol, drug and mental health treatments (Institute of Medicine, 2006). An application of process improvement to treatment for alcohol and drug disorders led to reductions in days to treatment admission and enhanced retention in care (Capoccia et al., 2007; McCarty et al., 2007).

1.1 Network for the Improvement of Addiction Treatment

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT) combined resources to support a demonstration that applied process improvement to treatment for alcohol and drug use disorders. The Network for the Improvement of Addiction Treatment is a learning community of addiction treatment centers seeking improved quality of treatment for alcohol and drug disorders. Participating sites learn and apply process improvement strategies. Four aims shape initial efforts at organizational change and process improvement: 1) reduce wait time between first request for service and treatment, 2) reduce client no-shows, 3) increase admissions, and 4) increase retention in care between the first and fourth treatment sessions.

An initial report on NIATx summarized program design and included a case study of an intensive outpatient treatment center where admission processes were changed so potential patients could begin treatment the next day; admissions increased, patients were more likely to remain in care and, in a two year period, the treatment center eliminated a $200,000 annual deficit and generated a $200,000 annual surplus (Capoccia et al., 2007). A cross-site evaluation examined data from 15 outpatient, intensive outpatient and residential units. The analysis found significant improvements in the delivery of care – a 37% decline in days to admission (from 19.6 to 12.4 days), an 18% gain in retention in care between the first and second treatment session (from 72% retention to 85% retention), and a 17% gain in retention between the first and third treatment session (from 62% retention to 73% retention (McCarty et al., 2007).

A weak evaluation design (post only quasi-experiment) and a lack of a no treatment comparison group, however, left the potential for study results to be due to large scale environmental changes rather than the introduction of the NIATx process improvement strategy. Replication of the results in an independent sample of treatment programs would increase confidence in the validity of study findings. The initial data, moreover, were restricted to a 15 month observation period. Analysis suggested that there was a slight but significant regression to baseline during the observation period and raised the possibility that gains would be lost over time. The NIATx evaluation, therefore, examined the implementation of process improvement in a second cohort of addiction treatment units to test replicability. Empirical assessments of long-term sustainability of gains in performance measures are relatively infrequent (Scheirer, 2005); data collection continued in the initial cohort for 20 months to assess long-term sustainability.

2.0 Methods

2.1 Selection of NIATx Members

Community-based not-for-profit corporations seeking to participate in NIATx submitted competitive proposals either to the RWJF or to the CSAT. For details on the initial round of applications and awards (10 from RWJF for 18 months and 13 from CSAT for 36 months) see the report on the initial results of the cross-site evaluation (McCarty et al., 2007). The RWJF made 15 additional awards in January 2005. The call for proposals was released in Spring 2004 and followed procedures similar to those used in the initial awards. The NIATx National Program Office at the University of Wisconsin received 180 six page brief proposals, requested full proposals from 44 and conducted 17 site visits in order to select the 13 full awards (approximately $100,000 for 18 months) and two partial awards (support for travel to participate in learning sessions).

2.2 Study Measures and Data Collection

The NIATx National Program Office and the NIATx National Evaluation Team collaborated to develop a spread sheet that simplified data collection and permitted each program to review progress toward NIATx goals. NIATx members extracted (electronically or manually) data from administrative records and completed an Excel spreadsheet. The spreadsheet recorded monthly admissions by level of care and recorded date of first contact (initial telephone call requesting care), date a clinical assessment was completed, treatment admission date, and date of the first, second, third and fourth treatment session. The spreadsheet also captured patient age, gender, race (white/non-white), Hispanic (yes/no), criminal justice involvement (yes/no) and primary drug (alcohol, cocaine, marijuana, opioids, methamphetamine, and other). Client names or patient identification numbers were not included on the spreadsheet to maintain confidentiality. After training on spreadsheet completion, NIATx members were asked to submit the spreadsheets (with patient identifiers deleted) monthly. Technical assistance was provided as needed. The spreadsheet was updated in January 2005 to correspond with the start of the second cohort of awards. The revised spreadsheet captured continued care more effectively and there was a visible shift toward improved retention. Data before and after the spreadsheet modification, therefore, were analyzed separately.

To assess changes in no-show rates and admissions, programs completed monthly project reports on the NIATx website. Data were available from 13 treatment units for the replication analysis and were aggregated for the first and last quarter of the project period to assess project impacts.

The Oregon Health and Science University Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved study procedures.

2.3 Eligibility Criteria

Replication Analysis

The replication analysis used data from the second cohort of 15 awards. Sites were included in the analysis if they provided 18 months of data between January 2004 and June 2005 and made process changes in outpatient and/or intensive outpatient levels of care. Treatment units that addressed detoxification, residential, or methadone services were not included because there was only one or two sites for each level of care. Two organizations did not provide sufficient data and two agencies provided only detoxification data. Fourteen treatment units (10 outpatient and 4 intensive outpatient units) (from 11 organizations – three agencies provided data for both levels of care) met eligibility criteria and were included in the analysis. During the 18 month observation period, the 14 treatment units reported delivering a first treatment session to 5,129 individuals (4,309 in outpatient services and 820 in intensive outpatient care).

Sustainability Analysis

The 15 treatment units (seven outpatient, 4 intensive outpatient, and 4 residential) analyzed in the initial cross-site evaluation were included in the sustainability analysis if they provided 20 additional months of data (January 2004 through August 2005). All of the treatment units qualified for inclusion in the analysis. During the 20 month follow-up period 8,251 patients received at least one treatment session (outpatient = 5,063; intensive outpatient = 1,735; residential = 1,453).

2.4 Data Analysis

The replication and sustainability analysis repeated the analysis completed for the initial cross-site evaluation (McCarty et al., 2007). Mean monthly access and retention rates were calculated for each site (i.e., one data point per site per month per measure). Polynomial regression models tested for trends within each site in the monthly rate data in conjunction with ARIMA (autoregressive integrated moving average) models to accommodate potential serial correlations. The analysis generated linear or quadratic trend regression models for each monthly rate time series and residuals were assessed for temporal correlations. In most cases neither the autocorrelation function nor the partial autocorrelation function were significant. Monthly rates, therefore, were treated as independent observations and averaged. Larger and smaller programs were weighted equally because the primary interest was program change over time; if weighted by number of observations, larger programs would dominate the analysis. A cubic smoothing spline function was fit to the monthly means for days from first contact to the first treatment and the percent of patients retained for a second, third and fourth units of care to confirm that the trend patterns were similar to those found with the polynomial regression models. Spline functions and linear regressions with ARIMA were calculated with R Statistical Language (R Development Core Team, 2005).

Because the spreadsheet modification shifted rates upward, the baseline for the sustainability analysis was January 2005 rather than December 2004 (the end of the initial observation period). The “Estimated End” data (December 2004) reported in Table 1 and Table 2 in the McCarty et al (2007) initial report on NIATx, therefore, differ slightly from the “Baseline” data (January 2005) reported in the current analysis.

Table 1.

Replication Analysis: Polynomial regression analysis of retention in care and days to treatment (January 2005 to June 2006)

| Level of Chare | Improvement %/month | F | p-value | January 2005 Baseline | June 2006 End | % change | Model* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retention session 1 to session 2 | |||||||

| Overall | 0.53 | 5.98 | 0.012 | 75.43 | 85.02 | 12.71% | Q |

| Outpatient | 0.49 | 12.07 | 0.003 | 78.11 | 86.93 | 11.28% | L |

| Intensive Outpatient | 0.59 | 5.88 | 0.013 | 72.01 | 82.58 | 14.68% | Q |

| Retention session 1 to session 3 | |||||||

| Overall | 0.47 | 8.87 | 0.009 | 69.21 | 77.73 | 12.30% | L |

| Outpatient | 0.48 | 7.98 | 0.012 | 63.29 | 71.86 | 13.53% | L |

| Intensive Outpatient | 0.62 | 4.32 | 0.033 | 65.74 | 76.87 | 16.94% | Q |

| Retention session 1 to session 4 | |||||||

| Overall | 0.57 | 10.86 | 0.005 | 57.12 | 67.45 | 18.10% | L |

| Outpatient | 0.48 | 4.45 | 0.051 | 48.28 | 56.88 | 17.81% | L |

| Intensive Outpatient | 0.83 | 4.44 | 0.031 | 55.75 | 70.73 | 26.86% | Q |

| Days between first contact and first treatment | |||||||

| Overall | −0.63 | 20.84 | 0.000 | 30.65 | 19.35 | −36.86% | Q |

| Outpatient | −0.68 | 16.54 | 0.000 | 33.42 | 22.30 | −33.29% | Q |

| Intensive Outpatient | −0.64 | 11.42 | 0.001 | 27.88 | 16.41 | −41.14% | Q |

L = linear model; Q = quadratic model

Table 2.

Sustainability Analysis: Polynomial Regression for months 16 to 35 for initial cohort of NIATx members

| Level of Chare | Improvement %/month | F | p-value | January 2005 Baseline | August 2006 End | % change | Model* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retention session 1 to session 2 | |||||||

| Overall | 0.12 | 0.56 | 0.46 | 88.03 | 90.33 | 2.62% | L |

| Outpatient | 0.11 | 0.60 | 0.45 | 81.89 | 84.17 | 2.79% | L |

| Intensive Outpatient | −0.02 | 2.35 | 0.13 | 89.34 | 89.04 | −0.34% | Q |

| Residential | 0.31 | 0.73 | 0.40 | 87.99 | 94.19 | 7.04% | L |

| Retention session 1 to session 3 | |||||||

| Overall | 0.16 | 0.76 | 0.39 | 78.29 | 81.44 | 4.03% | L |

| Outpatient | 0.09 | 5.22 | 0.02 | 70.91 | 72.81 | 2.68% | Q |

| Intensive Outpatient | −0.11 | 2.82 | 0.09 | 85.98 | 83.69 | −2.67% | Q |

| Residential | 0.50 | 1.72 | 0.21 | 77.37 | 87.38 | 12.94% | L |

| Retention session 1 to session 4 | |||||||

| Overall | 0.23 | 1.50 | 0.24 | 68.24 | 72.93 | 6.87% | L |

| Outpatient | 0.56 | 21.69 | 0.00 | 45.43 | 56.64 | 24.67% | L |

| Intensive Outpatient | −0.39 | 1.58 | 0.23 | 87.37 | 79.64 | −8.85% | L |

| Residential | 0.53 | 1.58 | 0.22 | 71.93 | 82.52 | 14.73% | L |

| Days between first contact and first treatment | |||||||

| Overall | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.88 | 10.96 | 11.10 | 1.25% | L |

| Outpatient | −0.15 | 4.83 | 0.04 | 18.04 | 14.99 | 16.94% | L |

| Intensive Outpatient | 0.10 | 1.83 | 0.19 | 3.83 | 5.80 | 51.37% | L |

| Residential | 0.07 | 0.76 | 0.39 | 11.01 | 12.51 | 13.62% | L |

L = linear model; Q = quadratic model

3.0 Results

3.1 Replication Analysis

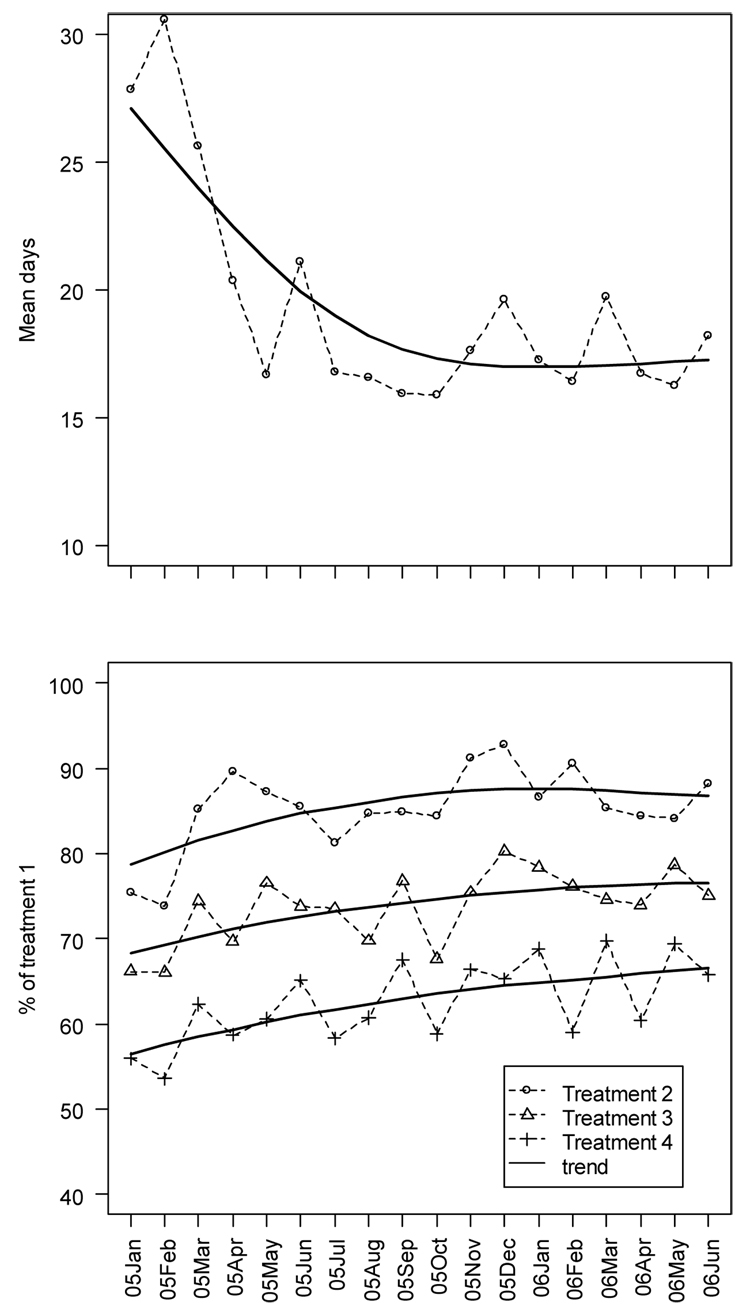

A polynomial regression analysis of days to admission and retention in care for the 14 treatment units providing outpatient and intensive outpatient services found a significant reduction in days to admission and significant increases in retention in care for the second, third and fourth unit of care. Table 1 summarizes the analyses and Figure 1 illustrates the trends over time.

Figure 1. Replication analysis.

Top Panel: Monthly mean days to first treatment session during an 18 month project period

Bottom Panel: Retention in care during an 18 month project period (percent returning for a second, third and fourth treatment session)

The solid lines represent the smoothed linear or quadratic spline trends

Over the 18 month observation period days between first contact and treatment admission declined from 30.7 to 19.4 days (−36.9%). A quadratic model suggested a linear decline of approximately 0.6 days per month offset with a small but significant return toward baseline of 0.1 days per month.

Retention in care improved significantly over the same period. Combining outpatient and intensive outpatient services, the percent of patients who returned for a second clinical session increased 12.7% (from 75.4% to 85.0%). A quadratic model fit the data and suggested about a 0.5% increase per month. Linear models provided the best fit for the percent of patients returning for a third session of care (from 69.2% to 77.7%; 12.3% gain) and among those returning for a fourth session of care (from 57.1% to 67.5%; 18.1% gain).

Analyses by level of care suggested that the improvement in outpatient retention fit a linear model and that improvement in intensive outpatient services fit a quadratic model. Outpatient retention increased 11.3% among patients returning for a second session of care (from 78.1% to 86.9%), 13.5% for patients returning for a third session of care (from 63.3% to 71.9%), and 17.8% for the fourth session of care (48.3% to 56.9%). Days between first contact and first treatment declined 33.3% (from 33.4 days to 22.3 days) in outpatient treatment; a quadratic model fit the data.

Patterns were similar for intensive outpatient services but the effects were a bit larger and quadratic models provided the best fit. Days to treatment declined 41.4% (from 27.9 to 16.4 days). Retention in care improved for the second (14.9%), third (16.9%) and fourth (26.9%) units of care.

3.2 No Show Rates and Admissions

Data on no-show rates for the assessment appointment and admissions were examined to assess program impacts on the other NIATx goals. Overall, no-show rates declined from 22% during the first three months of project participation to 13% in the last three months. Analysis of data from individual sites, however, suggests substantial variation. At baseline, two of 13 sites reported 0% no show rates and that increased to 8 sites at the end of the project period; four sites however exceeded 30 day waits at the end of the project period. There was a modest increase in admissions from 20.7 admissions per month to 23.4 admissions per month. Anecdotally, some programs made no effort to increase admissions because more admissions did not lead to increased funding.

3.3 Sustainability Analysis

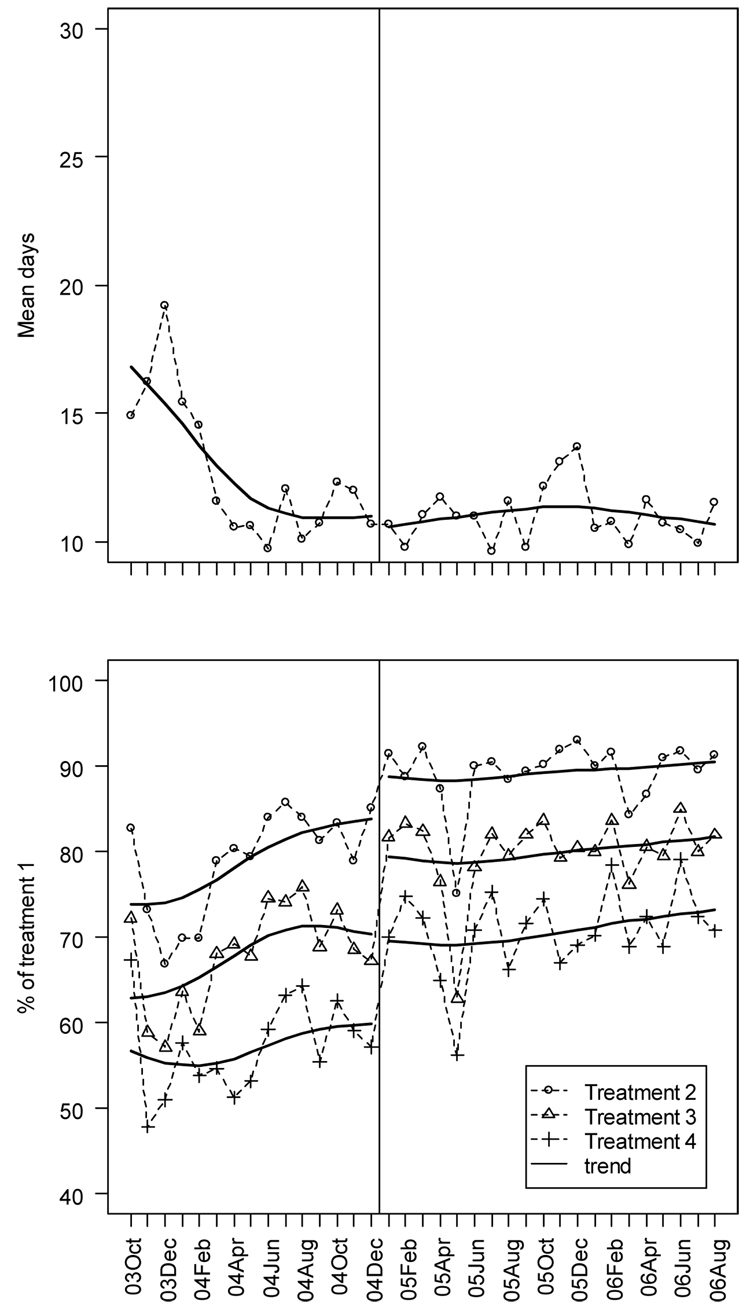

The 15 treatment units included in the initial evaluation analysis provided an additional 20 months to assess long-term sustainability of the process improvements. Table 2 summarizes the analyses and Figure 2 illustrates the trends over time. The vertical line marks the change in spreadsheets. The analysis of the first 15 months of data was reported previously (McCarty et al., 2007) and found significant reductions in days to treatment and significant improvements in retention in care. During the next 20 months of observation, changes in days to treatment and retention in care were not significant.

Figure 2. Sustainability analysis.

Top Panel: Monthly mean days to first treatment session during a 20 month follow-up

Bottom Panel: Retention in care during a 20 month follow-up (percent returning for a second, third and fourth treatment session)

The solid lines represent the smoothed linear or quadratic spline trends

The vertical line marks a change in the data collection system in January 2005

Analysis by level of care found a continued significant decline in days to treatment for outpatient services (from 18 days in January 2005 to 15 days in August 2006; a 16.9% improvement). Outpatient services also recorded continued but non-significant improvements in retention in care between the first and second session of care (from 81.9% to 84.2%; 2.8% improvement), and between the first and third session of care (70.9% to 72.8%; 2.7% improvement). There was a significant 24.7% improvement in retention for a fourth unit of care (45.4% to 56.6%). Neither residential nor intensive outpatient services provided evidence of continued declines in days to treatment and increases in retention.

4.0 Discussion

A second cohort of addiction treatment agencies participating in NIATx achieved 38% reductions in days between first contact and first treatment and 12% to 18% increases in retention in care. The rates of improvement are similar to those observed in the initial cross-site evaluation of NIATx: 37% reduction in days to treatment and 12% to 18% improvements in retention in care (McCarty et al., 2007). The consistency of results across independent cohorts of NIATx participants at separate points in time increases confidence in the replicability of findings and the influence of NIATx on the observed improvements.

The replication analysis included 18 months of data. Because of a change in spreadsheets in January 2005, the original analysis used a 15 month project period (McCarty et al., 2007). To confirm comparability of results, the replication sites were reanalyzed using a 15 month observation period. Exact results varied on estimated percent change but the pattern of results was similar for both the 15 month and 18 month analyses. The 18 month estimates of change compared to the 15 month estimates were more modest for the assessment of retention in care (13% versus 16% improved retention session 1 to 2, 13% versus 16% improved retention session 1 to 3, and 18% versus 23% improved retention session 1 to 4). The analysis of days to treatment suggested that the 18 month results were more positive than the 15 month results (37% versus 21% reductions in days to treatment).

Continued analysis of the original cohort of NIATx members found strong evidence that programs institutionalized changes in organizational processes and sustained the gains in access and retention. Programs sustained the improvements and the effects were not transient. Outpatient programs, moreover, continued to improve over the follow-up period. The NIATx process, therefore, facilitated organizational changes that enhanced access and retention and had a relatively persistent influence on the delivery of services. The slight return to baseline observed in the initial analysis was not amplified during the follow-up period.

The aggregated data conceal substantial variation among the participating sites. In the replication analyses, for example, decrements in days to treatment were apparent in four sites when month one was compared with month 18. Three of the four sites were below the mean in days to treatment at baseline and may have made little of no effort to improve their intake processes. Nine sites, conversely, reported substantial improvements (declines of 37 to 72%). One site reported only modest improvement (7%). Analyses of site variation are ongoing and may provide insight into more effective and less effective change strategies. Initial analyses suggest that client variables have relatively modest association with variation in days to treatment and retention in care (Hoffman, Ford, Choi et al, under review). Organizational variables and organizational change strategies are likely to have stronger influences.

4.1 Implications

Programs achieve and sustain improvements in treatment processes through attention to five principles of process improvement (Capoccia et al., 2007): 1) understand and involve the customer, 2) focus on issues that are central to the organization’s mission, 3) choose powerful change leaders, 4) seek ideas and support from outside the organization, and 5) use rapid cycles to pilot and test changes before they are institutionalized. Customer satisfaction is a key facet of process improvement. When executive directors described NIATx’s impact on their agencies, they frequently noted that the focus on the customer altered the culture of the corporation. It provided a consistent aim for change efforts. Staff at all levels embraced the concept of better customer service and tried new processes in order to improve the quality of care.

Walkthroughs are a strategy NIATx uses to enhance a customer focus and understand the patient’s experience (staff role play customers and walkthrough the process that is being improved). An analysis of qualitative descriptions of 327 admission walkthroughs completed as part of the NIATx application suggested that programs commonly found poor staff engagement with clients (e.g., telephone calls routed to the wrong person, inconsistent information from different staff, a lack of privacy, and information overload during intake), burdensome processes and paperwork (e.g., lengthy intake interviews that emphasized compliance with reimbursement requirements rather than the issues that brought the client to care), clients with complex lives and problems (e.g., multiple diagnoses made it difficult to develop treatment plans), and poor infrastructure (e.g., antiquated telephone systems, lack of electronic records) (Ford et al., 2007).

Interviews with managers and members of change teams suggested many valued the national learning sessions. NIATx members met annually and shared their successes and failures. The ability to exchange ideas and receive support from their colleagues motivated continued participation. Participants built strong collaborations with treatment programs in different regions of the country and copied changes that were successful elsewhere. This support system remains important to the members and many continue to participate in NIATx. The NIATx Change Leader Academy continues to train and support change leaders (Evans and Fitzgerald, 2006). Executive directors continue to attend learning sessions and support these activities through agency budgets rather than external awards.

4.2 Limitations

NIATx may not be a good fit for every organization providing treatment for alcohol and drug disorders. Evaluation interviews suggest that agencies with inconsistent leadership and unstable financial environments often abandoned the NIATx change efforts. Organizations that were stressed found it difficult to allocate staff time and energy to change efforts. Program change creates instability and when organizational survival is threatened it appears to be difficult to support additional stress.

The NIATx members do not fully represent the diversity of addiction treatment agencies. Competitive applications were used to select the initial membership. Although both larger and smaller agencies participated, smaller agencies had more difficulty because there was less organizational slack. It was also more difficult for smaller programs to implement and monitor change efforts – it simply required more time to see the effects of change. Finally, members received awards to help support the implementation of change teams and participation in national meetings. Although agencies tended to continue to support change efforts after the completion of the award period, it is likely to be more difficult to initiate change without additional resources.

Finally, the study only assessed retention in care through the first four sessions of care. Changes in long-term retention rates were not monitored. NIATx recognizes that long-term retention is more important than early retention. Most clients, however, leave care after only one or two sessions of care. Initial efforts to improve retention, therefore, must start with early retention.

These limitations are examined more closely in the next facets of NIATx. CSAT and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation support statewide process improvements through Strengthening Treatment Access and Retention: State Initiative (STAR-SI). Nine states have awards to spread NIATx process improvements throughout large portions of their states: Florida, Illinois, Iowa, Maine, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina and Wisconsin. (Montana uses state resources to participate in STAR-SI.) Participating treatment programs receive only modest awards (thousands of dollars rather than the $100,000+ initial awards). Support for participants is reduced even more in NIATx 200. Approximately 200 treatment programs from Massachusetts, Michigan, New York, Oregon, and Washington State are being randomized to four levels of support (learning session only, coaching only, interest circles only, and all three) and no additional funding. Use of state outcome monitoring systems will permit assessment of long-term outcomes and retention in care.

NIATx appears to be a useful strategy for treatment programs to learn process improvement. The continuing research will help establish the parameters for best practices for process improvement.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- Capoccia VA, Cotter F, Gustafson DH, Cassidy E, Ford J, Madden L, Owens BH, Farnum SO, McCarty D, Molfenter T. Making "stone soup": How process improvement is changing the addiction treatment field. Jt Comm J Qual Pt Saf. 2007;33:95–103. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(07)33011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans A, Fitzgerald M. Inspiring change leaders. Behav Healthc, 2006;26:14–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford J, Green CA, Hoffman KA, Wisdom JP, Riley KJ, Bergman FL, Molfenter T. Process improvement needs in substance abuse treatment: Admissions walkthrough results. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;33:379–389. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollop R, Whitby E, Buchanan D, Ketley D. Influencing skeptical staff to become supporters of service improvement: A qualitative study of doctors' and managers' views. Qual Safe Health Care. 2004;13:108–114. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2003.007450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham C, Kipping R, McLeod H. Redesigning work processes in health care: Lessons from the National Health Service. Milbank Q. 2003;81:415–439. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.t01-3-00062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman K, Ford JH, Choi D, Greenawalt J, Burke PF, Wisdom J, Shea M, Gallon S, McCarty D. Days to treatment and early retention among patients in treatment for alcohol and drug disorder. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.01.031. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Disorders: Quality Chasm Series. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner JE, Cody M, Thrush CR, Sullivan G, Rapp CG. Identifying factors critical to implementation of integrated mental health services in rural VA community-based outpatient clinics. J Behav Health ServRes. 2004;31:13–25. doi: 10.1007/BF02287335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landon BE, Wilson IB, McInnes K, Landrum MB, Hirschhorn L, Marsden PV, Gustafson D, Cleary PD. Effects of a quality improvement collaborative on the outcome of care of patients with HIV infection: The EQHIV Study. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:887–896. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-11-200406010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty D, Gustafson DH, Wisdom JP, Ford J, Choi D, Molfenter T, Capoccia V, Cotter F. The Network for the Improvement of Addiction Treatment (NIATx): Enhancing access and retention. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88:138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan K, Schall MW, Erb F, Nolan T. Using a framework for spread: The case of patient access in the Veterans Health Administration. Jt Comm J Qual Pt Safe. 2005;31:339–347. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(05)31045-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nugent WC. Building and supporting sustainable improvement in cardiac surgery: The Northern New England experience. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2005;9:115–118. doi: 10.1177/108925320500900202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor GT, Plume SK, Olmstead EM, Morton JR, Maloney CT, Nugent WC, Hernandez F, Clough R, Leavitt BJ, Coffin LH, Marrin CA, Wennberg D, Birkmeyer JD, Charlesworth DC, Malenka DJ, Quinton HB, Kasper JF The Northern New England Cardiovascular Disease Study Group. A regional intervention to improve the hospital mortality associated with coronary artery bypass graft surgery. JAMA. 1996;275:841–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker VA, Wubbenhorst WH, Young GJ, Desai KR, Charns MP. Implementing quality improvement in hospitals: The role of leadership and culture. Am J Med Qual. 1999;14:64–69. doi: 10.1177/106286069901400109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Scheirer MA. Is sustainability possible? A review and commentary on empirical studies of program sustainability. Am J Eval. 2005;26:320–347. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson T, Berwick DM, Cleary PD. What do collaborative improvement projects do? Experience from seven countries. Jt Comm J Qual Safe. 2003;29:85–93. doi: 10.1016/s1549-3741(03)29011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]