Abstract

Background

Astrocytomas are largely dependent on glycolysis to satisfy their bioenergetic requirements for growth and survival. Therapies that target glycolysis can potentially manage astrocytoma growth and progression. Dietary restriction of the high fat/low carbohydrate ketogenic diet (KD-R) reduces glycolysis and is effective in managing experimental mouse and human astrocytomas. The non-metabolizable glucose analogue, 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG), is a potent glycolytic inhibitor that can mimic effects of energy restriction both in vitro and in vivo, but can also produce adverse effects when administered at doses greater than 200 mg/kg. The goal here was to determine if low doses of 2-DG could act synergistically with the KD-R to better manage growth of the CT-2A malignant mouse astrocytoma.

Methods

The therapeutic effect of a KD-R supplemented with a low dose of 2-DG (25 mg/kg) was examined in adult C57BL/6J mice bearing the syngeneic CT-2A malignant astrocytoma grown orthotopically. Mice were fed the standard unrestricted diet for the first 3 days after tumor implantation prior to their separation into one of four diet groups fed either a standard rodent diet in unrestricted amounts (SD-UR) or a KD-R with or without 2-DG for 10 days. The KD-R was restricted to reduce body weight by about 20%. 2-DG was initiated 6 days after tumor implantation and was continued for 7 days. Brain tumors were excised and weighed.

Results

Energy intake, body weights, and CT-2A tumor weights were similar in the SD-UR and the SD-UR+2-2DG mouse groups over the dietary treatment period (days 3–13). Tumor weights were about 48% and 80% lower in the KD-R and in the KD-R+2-DG groups, respectively, than in the SD-UR group. Mouse health and vitality was better in the KD-R group than in the KD-R+2-DG group.

Conclusion

Astrocytoma growth was reduced more in the KD-R mouse group supplemented with 2-DG than in the mouse groups receiving either dietary restriction or 2-DG alone, indicating a synergistic interaction between the drug and the diet. The results suggest that management of malignant astrocytoma with restricted ketogenic diets could be enhanced when combined with drugs that inhibit glycolysis.

Background

Malignant astrocytomas represent a leading cause of cancer-related death [1-4]. The inability to effectively manage these tumors has been due in part to the unique anatomical and metabolic environment of the brain that prevents the complete resection of tumor tissue and impedes the delivery of therapeutic agents [5]. In contrast to normal brain cells, which can metabolize both glucose and ketone bodies for energy, brain tumors have a reduced capacity to metabolize ketone bodies and, like most malignant tumors, depend heavily on glycolysis for their metabolic energy according to the Warburg cancer theory [6-9]. Hence, therapies that can exploit the differences in energy metabolism between normal brain cells and brain tumor cells should be effective for tumor management [5,6,9].

The high fat/low carbohydrate, ketogenic diet (KD) has antiepileptic, anticonvulsant, and other neuroprotective effects in rodent disease models and in humans [10-17]. A reduction of circulating glucose levels coupled with an elevation of circulating ketone levels is thought to underlie the therapeutic effects [13,18,19]. Studies in children and in experimental brain tumor models showed that the KD administered in restricted amounts (KD-R) is effective in managing tumor growth and in extending survival [15,18,20]. The non-metabolizable glucose analogue 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG) is a potent glycolytic inhibitor that can replicate effects of glucose deprivation in normal cells and in cancer cells both in vitro and in vivo [21-25]. 2-DG is readily transported into cells and is phosphorylated by hexokinase, but cannot be metabolized further and accumulates in the cell. This leads to ATP depletion and the induction of cell-death. In this regard, 2-DG has been described as a CR-mimetic, a drug that mimics some aspects of calorie restriction [21,26]. Treatment of cancer patients with relatively high doses of 2-DG (greater than 200 mg/kg) was largely ineffective in managing tumor growth [27-29]. Side effects of 2-DG included elevated blood glucose levels, progressive weight loss with lethargy, and behavioral symptoms of hypoglycemia [23,27-29]. Reports that the ketogenic diet could be neuroprotective against hypoglycemic injury [12,16], and that it could also inhibit brain tumor growth by reducing glucose metabolism, suggest that combining the KD-R with low doses of 2-DG (e.g. 25 mg/kg BW) might improve the efficacy of the diet as an anticancer therapy. In the current study, the effects of a KD-R supplemented with a low dose of 2-DG were examined in adult C57BL/6J mice bearing the syngeneic CT-2A malignant astrocytoma grown orthotopically.

Mice and Experimental Astrocytoma

Mice of the C57BL/6J (B6) strain were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and were propagated in the Boston College Animal Care Facility as previously described [30]. Adult male mice (~14 weeks of age) were used in this study and were housed individually in plastic cages with filter tops containing Sani-Chip bedding (P.J. Murphy Forest Products Corp., Montville, NJ, USA). The syngeneic malignant mouse astrocytoma was implanted into the cerebral cortex as previously described [31]. The procedures for animal use were in strict adherence to the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee at Boston College. Other husbandry conditions were as previously described [30].

Dietary Regimens, Body Weight, and Food Intake Measurements

Two types of dietary regimens were employed in the study: the standard PROLAB RMH 3000 chow diet (SD) (Lab Diet, Richmond, IN, USA) and the lard-based ketogenic diet (KD) (Zeigler Bros., Inc., Gardners, PA, USA). All mice received PROLAB RMH 3000 chow prior to tumor implantation. The SD contained a balance of mouse nutritional ingredients and delivers 4.1 kcal g-1 gross energy, where fat, carbohydrate, protein, and fiber comprised 55, 520, 225, and 45 g kg-1 of the diet, respectively. The KD also contained a balance of mouse nutritional ingredients. According to the manufacturer's specification, the KD delivers 7.8 kcal g-1 gross energy, where fat, carbohydrate, protein, and fiber comprised 700, 0, 128, and 109 g kg-1 of the diet, respectively. The fat in this diet was derived from lard and the diet had a ketogenic ratio (fats: proteins + carbohydrates) of 5.48:1. Body weight and food intake of all mice was recorded daily (1:00 PM – 3:00 PM). Water was provided ad libitum for all mice.

All mice were fed the standard diet unrestricted for the first 3 days after tumor implantation. They were then separated into one of four diet groups fed either the standard diet in unrestricted amounts (SD-UR) or a KD-R with or without 2-DG (25 mg/kg) for 10 days. The four groups were matched for body weight (~28.8 g) prior to the initiation of the dietary regimens. Low dose treatment with 2-DG was initiated 6 days after tumor implantation and was continued for 7 days (Fig. 1B & Fig. 1C). The feeding paradigms for the KD-R and KD-R+2-DG groups were designed to reduce mouse body weights by ~20% relative to values recorded before the diets were initiated (3 days after tumor implantation). All mice were euthanized 13 days after tumor implantation.

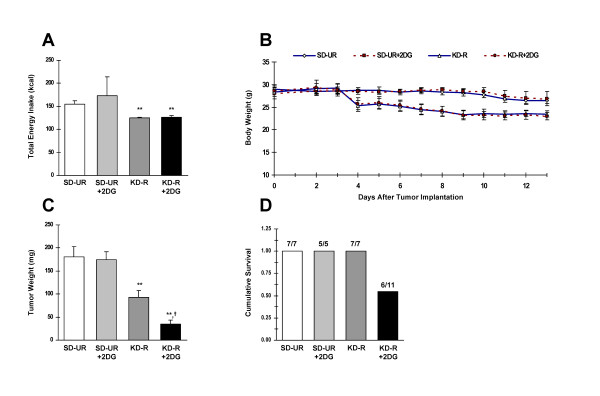

Figure 1.

Influence of the restricted ketogenic diet with or without 2-DG on total energy intake (A), body weight (B), tumor growth (C), and on cumulative survival (D) in mice bearing the orthotopically implanted CT-2A malignant astrocytoma. All mice were fed the standard high carbohydrate rodent diet in UR amounts for the first 3 days after tumor implantation prior to their separation into one of four diet groups (n = 5–11 mice/group) fed either SD-UR or a KD-R with or without 2-DG (25 mg/kg) for 10 days. The four groups were matched for body weight. 2-DG was initiated 6 days after tumor implantation and was continued for 7 days (B &C). As shown in (B), the feeding paradigm for the KD-R and KD-R+2-DG groups was designed to reduce body weights by ~20% relative to values recorded before the diet was initiated (3 days after tumor implantation). The average total energy intakes in (A) represent the number of kcals consumed by the indicated group over the dietary treatment period (day 3 to day 13). All values are expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. In (A &C), average values for the indicated group are significantly less than the average value for the SD-UR group at ** P < 0.01. The mean value for the KD-R+2DG group is significantly lower than the mean value for the KD-R group at † P < 0.01. No significant differences were observed between the SD-UR and SD-UR+2DG groups throughout the study. For (D), the number of tumor-bearing mice that were alive in each group at the conclusion of the study is listed as a ratio above each solid vertical bar (e.g. the "6/11" indicates that 6 of the 11 original mice were alive at the end of the study in the associated group).

Results and discussion

Our goal was to determine if low doses of 2-DG, when administered together with the KD-R, might produce synergistic effects. As our preliminary results showed that 2-DG at doses exceeding 250 mg/kg produced adverse effects to include weight loss, anorexia, and death (data not shown), we chose 2-DG at a dose of 25 mg/kg because this dosage did not alter food intake or body weight in tumor-bearing mice fed the KD-R compared with mice fed SD-UR. The therapeutic effects of dietary restriction arise largely from caloric restriction per se and not from the restriction of any specific dietary component such as proteins, vitamins, mineral, fats, or carbohydrates [15,32-34]. We did not include an unrestricted KD (KD-UR) group or a KD-UR+2-DG group in the study because we previously showed that the rate of tumor growth in mice fed an unrestricted KD is similar to that of mice fed SD-UR [15]. Moreover, unrestricted feeding of either the KD or standard high carbohydrate diets maintains high glucose levels, which provokes tumor angiogenesis and growth [5,32,35,36]. Restricted KDs maintain higher circulating ketone body levels and equally low glucose levels as restricted high carbohydrate standard diets [13,18]. Administration of the KD in restricted amounts also reduces adverse effects of the diet's high fat content, as fats are rapidly converted to ketone bodies for tissue energy metabolism [13]. Hence, we consider a restricted KD more therapeutic for brain cancer management than restricted high carbohydrate/protein diets. In contrast to 2-DG, which primarily reduces glycolysis through inhibition of hexokinase activity, dietary energy restriction acts as a broad spectrum inhibitor of multiple metabolic and signal transduction pathways without producing adverse effects [5].

Total energy intake was similar over the dietary treatment period (between 3 and 13 days after tumor implantation) in the SD-UR+2-DG and SD-UR groups, but more variability was noticed in the SD-UR+2-DG group (Fig 1A). Energy intake was similar between the KD-R and KD-R+2-DG groups over the dietary treatment period. Body weights were reduced to a similar degree (~20%) in the two groups fed the KD-R (Fig. 1A & Fig. 1B). We previously showed that matching body weights within control and treatment groups was absolutely critical for correct data interpretation [13,18]. In the current study, we found that administration of a low-dose of 2-DG had no significant affect on either body weight or on CT-2A tumor growth in mice fed the SD-UR (Fig. 1B & Fig. 1C). These results contrast with those of Zhu et al., who showed that administration of low dose 2-DG in an unrestricted standard high carbohydrate diet could reduce mammary tumor growth in rats [21]. The differences in the results between the two studies could be attributable to the different rodent species used, the mode of drug delivery, or to the location of the tumor (brain vs. subcutaneous flank).

We found that the average tumor weights for both the KD-R and KD-R+2-DG groups were significantly lower than those for the SD-UR group (48% and 80%, respectively) (Fig. 1C). These observations are consistent with prior studies showing that the KD-R can significantly reduce orthotopic CT-2A tumor growth [15,18], and also provide novel evidence that a low dose of 2-DG could act synergistically with the KD-R to further reduce growth in this mouse astrocytoma. The gross appearance of the mice bearing the CT-2A tumors in the UR and R groups in this study was similar to those that we showed previously for the restricted standard and ketogenic diets [32]. While tumor wet weight was reduced more in the KD-R + 2-DG group than in the KD-R group, facial appearance and skull size was similar in these groups. It is necessary to mention, however, that the combined therapy produced adverse effects on mouse health and vitality. Several mice in the KD-R+2-DG group died while the survivors appeared more lethargic than the mice in the KD-R group (Fig. 1D). We suggest that energy stress was greater in mice receiving the drug/diet combination than in mice receiving either dietary restriction or 2-DG alone. Nevertheless, the results show that 2-DG in combination with the restricted ketogenic diet was synergistic with regard to tumor growth and that potential adverse effects might be reduced with adjustments in either drug concentration or in diet restriction. Further studies will be needed to test this hypothesis.

Conclusion

Our findings provide novel evidence that the KD-R supplemented with a low dose of 2-DG was effective in reducing intracerebral tumor growth to a greater extent than was either 2-DG or the KD-R administered alone, suggesting a synergistic interaction between the drug and the diet. Although health and vitality were not as strong in the drug/diet group than in the KD-R group, adjustments in either 2-DG concentration or in dietary restriction could mitigate health detrimental effects. Our results suggest that combining drugs that inhibit glycolysis with restricted ketogenic diets could enhance inhibition of malignant astrocytoma growth.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

JM designed the study, performed the research, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript; PM helped design the study, and she also provided helpful comments during the drafting of this manuscript; TNS conceived of the initial study, provided support for the research, and helped to prepare the manuscript. All authors have read and approve the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The research was supported from NIH grants (NS 055195 and CA102135), and the Boston College research expense fund.

Contributor Information

Jeremy Marsh, Email: jmarsh@aecom.yu.edu.

Purna Mukherjee, Email: mukherjp@bc.edu.

Thomas N Seyfried, Email: thomas.seyfried@bc.edu.

References

- Nicholson HS, Kretschmar CS, Krailo M, Bernstein M, Kadota R, Fort D, Friedman H, Harris MB, Tedeschi-Blok N, Mazewski C, Sato J, Reaman GH. Phase 2 study of temozolomide in children and adolescents with recurrent central nervous system tumors: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. Cancer. 2007;110:1542–1550. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry JK, Snyder JJ, Lowry PW. Brain tumors in the elderly: recent trends in a Minnesota cohort study. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:922–928. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.7.922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PG, Buffler PA. Malignant gliomas in 2005: where to GO from here? Jama. 2005;293:615–617. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.5.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jukich PJ, McCarthy BJ, Surawicz TS, Freels S, Davis FG. Trends in incidence of primary brain tumors in the United States, 1985–1994. Neuro-oncol. 2001;3:141–151. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/3.3.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh J, Mukherjee P, Seyfried TN. Akt-dependent proapoptotic effects of dietary restriction on late-stage management of a PTEN/TSC2-deficient mouse astrocytoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:7751–7762. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiebish MA, Han X, Cheng H, Chuang JH, Seyfried TN. Cardiolipin and electron transport chain abnormalities in mouse brain tumor mitochondria: Lipidomic evidence supporting the Warburg theory of cancer. J Lipid Res. 2008 doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800319-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburg O. The Metabolism of Tumours. New York, Richard R Smith; 1931. [Google Scholar]

- Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956;123:309–314. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3191.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seyfried TN, Mukherjee P. Targeting energy metabolism in brain cancer: review and hypothesis. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2005;2:30. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-2-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman JM, Kossoff EH, Freeman JB, Kelly MT. The Ketogenic Diet: A Treatment for Children and Others with Epilepsy. Fourth. New York, Demos; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Veech RL. The therapeutic implications of ketone bodies: the effects of ketone bodies in pathological conditions: ketosis, ketogenic diet, redox states, insulin resistance, and mitochondrial metabolism. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2004;70:309–319. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins ML. Cerebral metabolic adaptation and ketone metabolism after brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:1–16. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantis JG, Centeno NA, Todorova MT, McGowan R, Seyfried TN. Management of multifactorial idiopathic epilepsy in EL mice with caloric restriction and the ketogenic diet: role of glucose and ketone bodies. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2004;1:11. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman AL, Vining EP. Clinical aspects of the ketogenic diet. Epilepsia. 2007;48:31–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.00914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seyfried TN, Sanderson TM, El-Abbadi MM, McGowan R, Mukherjee P. Role of glucose and ketone bodies in the metabolic control of experimental brain cancer. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:1375–1382. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada KA, Rensing N, Thio LL. Ketogenic diet reduces hypoglycemia-induced neuronal death in young rats. Neurosci Lett. 2005;385:210–214. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasior M, Rogawski MA, Hartman AL. Neuroprotective and disease-modifying effects of the ketogenic diet. Behav Pharmacol. 2006;17:431–439. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200609000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W, Mukherjee P, Kiebish MA, Markis WT, Mantis JG, Seyfried TN. The calorically restricted ketogenic diet, an effective alternative therapy for malignant brain cancer. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2007;4:5. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-4-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene AE, Todorova MT, Seyfried TN. Perspectives on the metabolic management of epilepsy through dietary reduction of glucose and elevation of ketone bodies. J Neurochem. 2003;86:529–537. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebeling LC, Miraldi F, Shurin SB, Lerner E. Effects of a ketogenic diet on tumor metabolism and nutritional status in pediatric oncology patients: two case reports. J Am Coll Nutr. 1995;14:202–208. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1995.10718495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z, Jiang W, McGinley JN, Thompson HJ. 2-Deoxyglucose as an energy restriction mimetic agent: effects on mammary carcinogenesis and on mammary tumor cell growth in vitro. Cancer research. 2005;65:7023–7030. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aft RL, Zhang FW, Gius D. Evaluation of 2-deoxy-D-glucose as a chemotherapeutic agent: mechanism of cell death. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:805–812. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh D, Banerji AK, Dwarakanath BS, Tripathi RP, Gupta JP, Mathew TL, Ravindranath T, Jain V. Optimizing cancer radiotherapy with 2-deoxy-d-glucose dose escalation studies in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Strahlenther Onkol. 2005;181:507–514. doi: 10.1007/s00066-005-1320-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, Zhang F, Bradbury CM, Kaushal A, Li L, Spitz DR, Aft RL, Gius D. 2-Deoxy-D-glucose-induced cytotoxicity and radiosensitization in tumor cells is mediated via disruptions in thiol metabolism. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3413–3417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laszio J, Humphreys SR, Goldin A. Effects of glucose analogues (2-deoxy-D-glucose, 2-deoxy-D-galactose) on experimental tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1960;24:267–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang HT, Hwang ES. 2-Deoxyglucose: an anticancer and antiviral therapeutic, but not any more a low glucose mimetic. Life Sci. 2006;78:1392–1399. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dills WL, Jr, Kwong E, Covey TR, Nesheim MC. Effects of diets deficient in glucose and glucose precursors on the growth of the Walker carcinosarcoma 256 in rats. J Nutr. 1984;114:2097–2106. doi: 10.1093/jn/114.11.2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cay O, Radnell M, Jeppsson B, Ahren B, Bengmark S. Inhibitory effect of 2-deoxy-D-glucose on liver tumor growth in rats. Cancer Res. 1992;52:5794–5796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau BR, Laszlo J, Stengle J, Burk D. Certain metabolic and pharmacologic effects in cancer patients given infusions of 2-deoxy-D-glucose. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1958;21:485–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flavin HJ, Wieraszko A, Seyfried TN. Enhanced aspartate release from hippocampal slices of epileptic (El) mice. J Neurochem. 1991;56:1007–1011. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb02021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seyfried TN, el-Abbadi M, Roy ML. Ganglioside distribution in murine neural tumors. Mol Chem Neuropathol. 1992;17:147–167. doi: 10.1007/BF03159989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seyfried TN, Mukherjee P. Anti-Angiogenic and Pro-Apoptotic Effects of Dietary Restriction in Experimental Brain Cancer: Role of Glucose and Ketone Bodies. In: Meadows GG, editor. Integration/Interaction of Oncologic Growth Cancer Growth and Progression. Vol. 15. New York: Kluwer Academic; 2005. pp. 259–270. [Google Scholar]

- Tannenbaum A. The genesis and growth of tumors: II. Effects of caloric restriction per se. Cancer Res. 1942;2:460–467. [Google Scholar]

- Tannenbaum A. Nutrition and cancer. In: Homburger F, editor. Physiopathology of Cancer. NY: Paul B. Hober; 1959. pp. 517–562. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee P, Abate LE, Seyfried TN. Antiangiogenic and proapoptotic effects of dietary restriction on experimental mouse and human brain tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:5622–5629. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee P, El-Abbadi MM, Kasperzyk JL, Ranes MK, Seyfried TN. Dietary restriction reduces angiogenesis and growth in an orthotopic mouse brain tumour model. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:1615–1621. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]