Abstract

The alkyllysophospholipid (ALP) analogues Mitelfosine and Edelfosine are anticancer drugs whose mode of action is still the subject of debate. It is agreed that the primary interaction of these compounds is with cellular membranes. Furthermore, the membrane-associated protein CTP: phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase (CCT) has been proposed as the critical target. We present the evaluation of our hypothesis that ALP analogues disrupt membrane curvature elastic stress and inhibit membrane-associated protein activity (e.g. CCT), ultimately resulting in apoptosis. This hypothesis was tested by evaluating structure–activity relationships of ALPs from the literature. In addition we characterized the lipid typology, cytotoxicity and critical micelle concentration of novel ALP analogues that we synthesized. Overall we find the literature data and our experimental data provide excellent support for the hypothesis, which predicts that the most potent ALP analogues will be type I lipids.

Keywords: alkylphosphocholines, anticancer, type I lipids, CTP: phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase, curvature elastic stress, alkyllysophospholipids

1. Introduction

Since the discovery of the cytotoxic and antitumour properties of lysophosphatidylcholine analogues (Munder 1982; Brachwitz et al. 1987; Brachwitz & Vollgraf 1995), a number of alkylphosphocholine (APC) and alkyl-lysophospholipid (ALP) analogues have been developed for clinical use. Two compounds in particular have emerged as important chemotherapeutic agents: ET-18-OMe from the ALP series of materials (1) and hexadecylphosphocholine (HDPC) (2) from the APC series. These compounds have elicited considerable interest because while it is clear that their mode of action does not involve intercalation or direct interaction with DNA, the details of the mechanisms that underlie their potent biological activity remain unclear. Over the past few years a consensus has emerged that CTP: phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase (CCT; Geilen et al. 1996; Jackowski & Boggs 1998; Jimenez-Lopez et al. 2002) is the initial cellular target of the ALP and APC agents. CCT, a translocation protein, is a rate-determining enzyme in the biosynthesis of phosphatidylcholine (PtdCho) phospholipids (Kent 1997; Jackowski & Baburina 2002). In most mammalian cells, CCT catalyses the only route for introducing choline into the pathway that manufactures PtdCho lipids; regulation of CCT activity appears to be critical for cell membrane homeostasis and cell survival, especially during mitosis (Jackowski 1994, 1996). The key experimental evidence that points to CCT being the target for ALP and APC compounds can be summarized as follows.

ET-18-OMe and HDPC inhibit CCT activity and both are cytotoxic agents in vitro (Vogler et al. 1996; Jimenez-Lopez et al. 2002).

Choline incorporation is blocked by both compounds in vitro (Boggs et al. 1995); choline-deficient cells enter into a state of stasis and then undergo apoptosis, as do cells treated by ALP analogues (Konstantinov et al. 1998a).

Both HDPC and ET-18-OMe inhibit PtdCho biosynthesis (Jackowski & Boggs 1998), leading to a rise in ceramide, which marks the onset of apoptosis (Wieder et al. 1998).

The cytotoxic and cytostatic effects of HDPC and ET-18-OMe on HL-60 cells are attenuated by exogenous lysophosphatidylcholine, an alternate precursor for PtdCho production, which bypasses CCT (Boggs et al. 1998).

There is agreement in the literature that CCT activity is regulated by the lipid composition of the membranes to which it is attached (Jamil et al. 1993; Attard et al. 2000). Recently, it has been suggested that the mechanism through which CCT is regulated involves membrane curvature elastic stress (Attard et al. 2000). More specifically, it has been postulated that type II lipids within a membrane lead to an increase in the membrane curvature elastic stress and that this, in turn, leads to increased partitioning of CCT onto the membrane. Since cytosolic CCT is essentially inactive, the net effect of type II lipids in the membrane is to increase the concentration of enzymatically active CCT. The converse situation applies in the case of type I lipids. These decrease the curvature elastic stress in a membrane, leading to decreased partitioning of CCT onto the membrane and hence lower quantities of active CCT. We use the terms type I, type 0 and type II lipids to describe the self-assembly of amphiphiles into aggregates and lyotropic liquid crystalline phases. Type I lipids are non-bilayer lipids that form aggregates whose polar–apolar interface curves away from the aqueous domains, while type II lipids are non-bilayer-forming lipids that form aggregates in which the interface curves towards these domains. Type 0 lipids are bilayer-forming lipids.

Since ALP and APC analogues are generally type I amphiphiles and inhibit CCT, we hypothesize that the principal and universal mode of action of all metabolically stable antineoplastic homologues of ALPs and APCs is the inhibition of CCT through the reduction of membrane curvature elastic stress, with a subsequent decrease in the biosynthesis of PtdCho leading to cytostasis, an increase in ceramide levels and ultimately apoptosis.

Membrane curvature elastic stress arises from the summation of the lateral stresses in a membrane (see Marsh (2006) for a detailed explanation). The magnitude of the curvature elastic stress in a monolayer, gc, can be represented by the Helfrich Hamiltonian (Helfrich 1973)

| (1.1) |

In this Hamiltonian A is the cross-sectional area per molecule; c1 and c2 are the principal curvatures at the interface (with the convention that an interface with negative curvature curves towards water); c0 is the spontaneous curvature of the monolayer; κ is the bending rigidity; and κG is the Gaussian curvature modulus. Stored curvature elastic energy arises from non-zero spontaneous curvature in each of the monolayers that compose a bilayer lipid membrane such that each monolayer wishes to bend, but is prevented from doing so by being apposed to the other monolayer. To a first-order approximation, the curvature elastic stress is governed by a combination of the two material parameters c0 and κ.

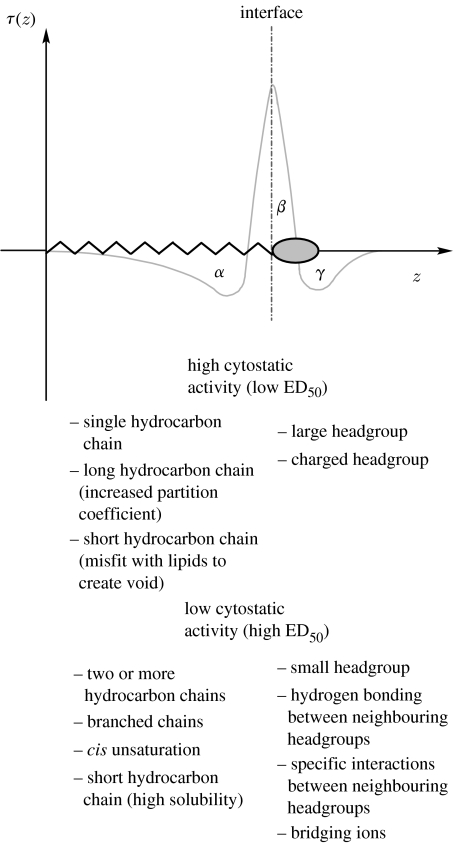

The likelihood that an amphiphile can reduce the stored curvature elastic energy when it partitions into a membrane can be predicted qualitatively by considering the interactions that contribute to the lateral stress profile within an aggregate (figure 1; Seddon 1990). In general, the lateral stress profile of a monolayer can be divided into three distinct regions (α, β, γ). The spontaneous mean curvature (c0) of the monolayer is dependent on the balance of the areas under the curve in these regions. When the areas are such that α<γ, then type I behaviour is expected and the monolayer will seek to curve away from the polar–apolar interface (i.e. c0 is positive). Conversely, if α>γ then type II behaviour is expected and the monolayer will want to curve towards the polar–apolar interface (i.e. c0 is negative). Typically, the area associated with the hydrocarbon region (α) shows big changes if a saturated hydrocarbon chain is replaced by a branched chain, or by an unsaturated chain containing one or more cis double bonds. Changes in the area γ are caused by hydration, electrostatic repulsion, specific chemical interactions between neighbouring headgroups or interactions with counterions. Area β is dependent on the interfacial tension, and its magnitude must be equal and opposite to the sum of areas α and γ in order to have a stable monolayer. These considerations lead to a set of qualitative predictors of amphiphile typology which are widely used in surfactant science through the semi-quantitative concept of the ‘critical packing parameter’.

Figure 1.

The lateral stress profile of an amphiphilic molecule, where z is the distance from the interface, τ(z) is the stress at z, where stress is the negative of pressure. Annotations describe the ‘rules of thumb’, derived from the lateral pressure profile, which we have used to predict the structure activity relationships of ALP and APC analogues.

Broadly speaking, type I amphiphiles tend to have larger cross-sectional headgroup areas and smaller hydrocarbon chain cross-sectional areas (type I molecular shape). Examples include lipids with bulky, or charged headgroups, and with saturated and relatively short alkyl chains. Conversely, type II amphiphiles tend to have larger hydrocarbon cross-sectional areas than headgroup cross-sectional areas (type II molecular shape), generally resulting from cis unsaturation, or have attractive interactions between neighbouring headgroups.

These qualitative predictors of amphiphile aggregation behaviour have serious limitations. In particular, the effective area per headgroup can change significantly as a function of the concentration of the amphiphile or lipid; consequently, classification of an amphiphile as type I or type II requires experimental data, and specifically an analysis of its phase behaviour. Strongly type I amphiphiles have phase diagrams that are dominated by micellar solutions at low concentrations and normal topology lyotropic liquid crystalline phases (e.g. micellar cubic, hexagonal) at higher concentrations. Type II amphiphiles have phase diagrams that are dominated by complex aggregates at low concentrations (e.g. vesicles, hexosomes or cubosomes) and inverse topology liquid crystal phases at higher concentrations. Although phase behaviour can provide unequivocal confirmation of type I behaviour, there are situations where it can lead to erroneous conclusions. These situations arise because the effect of an amphiphile on stored curvature elastic energy is dependent on the lipid composition of the target membrane. This means that even amphiphiles whose phase diagrams exhibit inverse topology phases can still lead overall to the inhibition of CCT if they are less strongly type II than the constituents of the target membranes.

The cytotoxic or cytostatic potency of an amphiphile that acts by inhibiting CCT through a reduction in the stored elastic energy of membranes can be described semi-quantitatively by

| (1.2) |

where n is the number of molecules—comprising both lipids and type I amphiphiles—surrounding the binding domain of CCT, and E0 is a constant. According to this equation, an increase in the fraction of molecules that have a positive spontaneous curvature, c0, leads to a decrease in E (the degree of cell survival), since c1 is negative. The quantity E is analogous to the ED50 that is measured in experiments on cytotoxicity.

The extension of this analysis to the relationships between the molecular structure of cytotoxic amphiphiles, their effects on stored curvature elastic energy in a lipid membrane and their ED50 values may be achieved using a series of qualitative ‘rules of thumb’ that are derived from the profile of interactions along the length of an amphiphile. These are summarized schematically in figure 1. In general, amphiphiles that form normal topology phases would be expected to be highly cytotoxic because they would result in a significant reduction of the stored elastic energy in a membrane. In particular we would expect that amphiphiles with charged headgroups would be potent cytotoxic agents. We would also expect that amphiphiles with sterically bulky headgroups will be effective at reducing stored curvature energy and hence exhibit cytotoxic properties. Furthermore, we predict that the closer the steric bulk is to the polar–apolar interface, the more effective the amphiphile will be at inhibiting the growth of cancer cells.

We have tested these simple predictions using literature data as well as data on compounds we have synthesized and evaluated in our laboratories and have found a remarkable degree of agreement covering a very wide diversity of amphiphile chemical structures. In particular we have found that cytotoxic analogues of ALPs and APCs are type I lipids.

The wide range of biological effects that ALP analogues have on normal and malignant cells has been reviewed extensively (Brachwitz & Vollgraf 1995; Principe & Braquet 1995; Berkovic 1998). Brachwitz (Brachwitz & Vollgraf 1995) provides details of a variety of ALP analogue structures that have been reported to be cytotoxic or cytostatic. When the qualitative amphiphile classification scheme outlined earlier is applied to this extensive set of compounds, it becomes clear that type I amphiphiles dominate. For example; the O-alkylglycerophosphocholines, of which ET-18-OMe (1) is the best known homologue, bear a single saturated hydrocarbon chain and have a zwitterionic headgroup. These features conform to a type I molecular shape, corresponding to a hydrocarbon cross-sectional area that is smaller than the cross-sectional area of the headgroup. Experimentally, ET-18-OMe prevents the formation of inverse hexagonal phases in model membranes (Torrecillas et al. 2006) and the analogous ET-16-OMe forms normal typology micelles at low concentration in water (Dick & Lawrence 1992), confirming that it is a type I amphiphile. Table 1 lists selected examples of cytotoxic O-alkylglycerophosphocholines. Compounds 4–6 and 7–9 have been shown to have cytotoxic activities independent of the position of the main structural elements (Brachwitz et al. 1979, 1982, 1984), an observation that supports the hypothesis that it is the type I molecular shape that is critical for activity. Furthermore, branching in the alkyl chain, for example by introduction of phytanyl groups (10 and 11), causes a 3 to 10-fold decrease in cytotoxic activity when compared with ET-18-OMe (1) (Hoffman et al. 1984).

Table 1.

A selection of ALP and APC analogues from the literature with type I molecular shape.

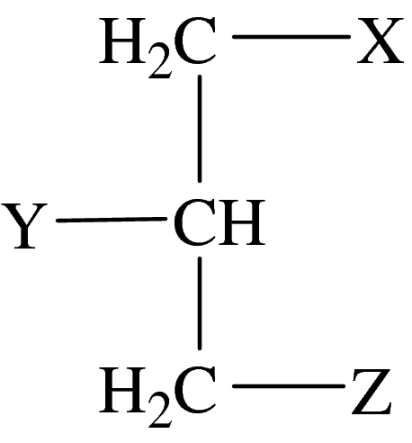

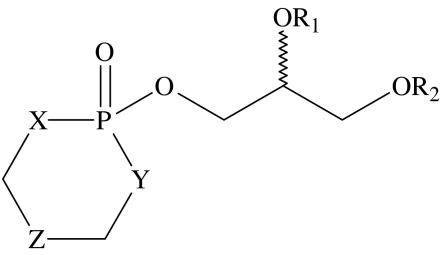

glycerol backbone structure

|

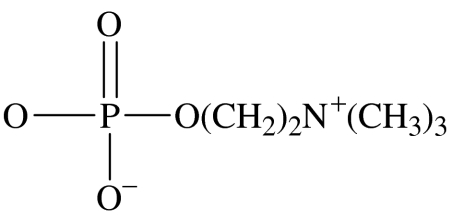

headgroup structure

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound number | X | Y | Z | comments |

| 1 | OC18H37 | OCH3 | headgroup | ET-18-OMe |

| 2 | na | na | headgroup | C16H33-Z (HDPC) |

| 3 | OC14H29 | OCH3 | headgroup | ET-14-OMe |

| 4 | OC16H33 | Cl, F | headgroup | rac |

| 5 | OC16H33 | headgroup | Cl, F | rac |

| 6 | Cl, F | OC16H33 | headgroup | rac |

| 7 | OC16H33 | OCH2CF3 | headgroup | rac |

| 8 | OC16H33 | headgroup | OCH2CF3 | rac |

| 9 | OCH2CF3 | OC16H33 | headgroup | rac |

| 10 | OC2H4(C-C3H6)3-CH(CH3)3 | OCH3 | headgroup | sn |

| 11 | headgroup | OCH3 | OC2H4(C-C3H6)3-CH(CH3)3 | sn |

| 12 | SC16H33 | CH2OCH3 | headgroup | rac, BM41.440 |

| 13 | na | na | headgroup |  |

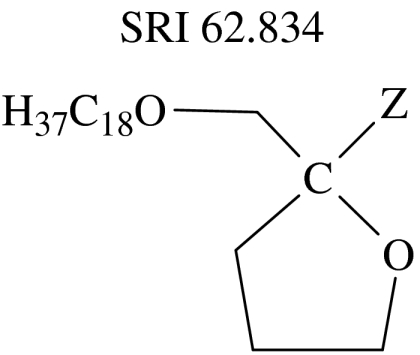

Compounds such as BM 41.440 (12) which retain the type I characteristic of a single, unbranched and saturated hydrocarbon chain are also highly cytotoxic (Fromm et al. 1987; Schick et al. 1987; Hanauske et al. 1992). SRI 62.834 (13), which differs substantially from ET-18-OMe through its cyclic headgroup, still retains a type I molecular shape and is also highly cytotoxic (Houlihan et al. 1987; Dive et al. 1991). Similarly, the O-alkylethyleneglycophosphocholine homologues have type I molecular shape and are also cytotoxic (Honma et al. 1983).

HDPC (2) is a type I amphiphile as confirmed by the phase diagram presented in this study; by analogy other APC analogues will also be strongly type I amphiphiles. Structure–activity studies show that shortening the alkyl chain of HDPC or introducing unsaturation within it reduces cytotoxicity (Unger et al. 1992). The relative cytotoxic effects of a homologous series of amphiphiles, containing a single hydrocarbon chain, in which only the length of this chain is varied, provide a challenging test of the hypothesis that is embodied by equation (1.2). In this equation both n and c0 are dependent on the length (λ) of the amphiphile's hydrocarbon chain. Furthermore, in equation (1.2) the composition of the amphiphiles that surround the CCT-binding domain is dependent on the extent to which the antineoplastic amphiphiles partition into the membrane. To a first approximation, we would expect n(λ) to be a linear function of λ for amphiphiles that contain a single hydrophobic chain. The functional dependence of c0(λ) on λ is not known, but phenomenologically it is reasonable to assume a power law dependence, λγ, in which the exponent γ<1. This means that equation (1.2) assumes the general form

| (1.3) |

where the constants ζ≥0, A≥0, B<0, C>0 and D>0 depend on the chemical structure of the amphiphile. The first part of equation (1.3) accounts for the observation that amphiphiles with longer hydrocarbon chains partition more readily into membranes than amphiphiles with shorter chains. While this should result in an enhanced cytotoxicity, the second part of equation (1.3) highlights the fact that as λ increases, the spontaneous curvature of the membrane will become less positive, thereby activating CCT and counteracting cytotoxicity. Conversely, for amphiphiles with short chains, equation (1.3) predicts that their lower partitioning will be counteracted by their higher type I characteristics, which drive the spontaneous curvature to become more positive. Correlations between alkyl chain length and cytotoxicity have been observed in a variety of cell lines; generally, the ED50 decreases as the length of the alkyl chain increases, but the rate of decrease is slower than expected from a simple exponential dependence. This correlates well with the ‘stretched exponential’ component of equation (1.3). In several studies it appears that activity goes through a maximum (minimum in ED50) at a chain length of 16–18 carbon units (Andreesen et al. 1978; Morris-Natschke et al. 1986; Vogler et al. 1993; Geilen et al. 1994; Konstantinov et al. 1998a,b). Furthermore, Geilen et al. found that activity went through a maximum as chain length increased, but the amount of active compound in the membrane increased with chain length (Geilen et al. 1994), giving excellent experimental support for equation (1.3).

Equation (1.3) also explains why short-chain dialkyl (typically dioctyl) PtdCho analogues (Tarnowski et al. 1978) and the didecyl CP-46 665 prepared by Pfizer show similar cytotoxic activity to ET-18-OMe and BM41.440 (Danhauser et al. 1987). Introduction of the short-chain dialkyl analogues into a membrane leaves an area of ‘free space’ below the alkyl chains that the longer chain exogenous lipids will need to fill; consequently, there is a decrease in the curvature elastic stress within the membrane. The chain length versus activity relationship of these compounds will also go through a pattern of activity as that of the single chain derivatives but the greater hydrophobicity of the dialkyl compounds will cause maximum potency to occur at a shorter chain length before the larger hydrocarbon cross-sectional area dominates and decreases potency as observed (Kudo et al. 1987).

It is interesting to note that hexadecylphosphonocholine has cytotoxic activity similar to its analogue HDPC (Langen et al. 1992). Exchange of the phospholipid headgroup from choline to N,N-dimethylethanolamine (Brachwitz et al. 1982) and then to serine (Langen et al. 1992) and phosphoinositol (Noseda et al. 1987) does not abrogate activity, although some decrease is observed. Furthermore, in the case of ALP analogues, the order of substituents on the glycerol backbone does not affect activity significantly (Langen et al. 1992). This is expected since such isomerism has minimal effects on the aggregation properties of many lipids.

As the study of the cytotoxicity of ALP and APC analogues developed, compounds with structures very different from the basic phosphocholine form of the ALP and APCs were reported in the literature as cytotoxic. Examples include the N-acyl derivatives of O-alkylglycerophospho- and alkylphospho-l-serines, nucleoside-5′-diphosphate and nucleoside-5′-phosphonophosphate-alkylglycerols prepared by Brachwitz (Brachwitz & Vollgraf 1995), O-alkylglycero-myo-inositols (Noseda et al. 1987; Ishaq et al. 1989) and a range of non-phosphorus-containing analogues. Within the group of non-phosphorus-containing analogues, glycolipid analogues of ET-18-OMe have been reported to be active (Weber & Benning 1988). Neutral lipids such as 1-O-hexadecyl-2-chloro-2-deoxyglycerol are also cytotoxic (Langen et al. 1979) as are the alkyl ether glycerolipids (Honma et al. 1991). An analysis of the structures of these compounds shows that they share the common characteristic of being amphiphilic with type I molecular characteristics.

Several issues were encountered when evaluating the literature on cytotoxic amphiphiles that limit the extent to which published data can be used to test our hypothesis. The two most significant issues are the wide diversity of experimental procedures and protocols employed to determine the ED50, which poses serious challenges when comparing data from different studies, and the sparseness of information on the aggregation or phase behaviour of the novel compounds. In view of these limitations, we designed and synthesized in our laboratories a range of analogues of ALPs and APCs which would test predictions resulting from our hypothesis. These compounds included glycolipid analogues and some non-phosphorus-containing amphiphiles. In this way we were able to collect cytotoxicity data and classify the bioactive amphiphiles by investigating their aggregation behaviour, specifically their lyotropic liquid crystal properties.

2. Experimental procedures

RPMI medium, foetal calf serum and antibiotic–antimiotic solution were purchased from Invitrogen; 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), trypan blue, ethanol and isopropanol were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Octaethylene glycol ethers (42–46) and quaternary ammonium amphiphiles (39–41) were purchased from Fluka.

HDPC was purchased from Alexa Biochemicals. Syntheses of the phosphoramide phospholipid analogues (Mackenzie 1995; 14–27, table 2), of the heterocyclic ALPs (Wan 1997; 28–38, table 3), of the classic type I amphiphiles (Wan 1997; 39–46, table 4) and of the glycolipid compounds (Blackaby 1997; 47–55, table 5) have been published previously.

Table 2.

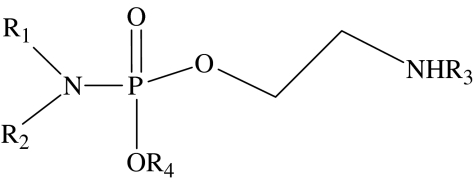

The structure, cytotoxicity and lipid typology of phosphoramide analogues.

phosphoramide general structure

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound number | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | EC50/μMa | lipid typologyb |

| 14 | C6H13 | H | CH3 | CH3 | 1000 | undetermined |

| 15 | C12H25 | H | CH3 | CH3 | 230 | type I |

| 16 | C16H33 | H | CH3 | CH3 | 110 | type I |

| 17 | C18H37 | H | CH3 | CH3 | 140 | type I |

| 18 | oleyl | H | CH3 | CH3 | 130 | type I |

| 19 | C18H37 | H | CH3 | C2H5 | 40 | type I |

| 20 | C6H13 | C6H13 | CH3 | CH3 | 140 | undetermined |

| 21 | C3H7 | C15H31 | CH3 | CH3 | 23 | type I |

| 22 | C6H13 | C12H25 | CH3 | CH3 | 77 | undetermined |

| 23 | C12H25 | H | H | CH3 | 250 | type I |

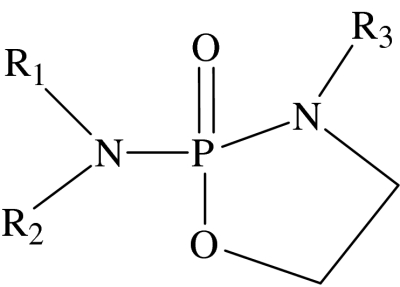

cyclic phosphoramide general structure

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound number | R1 | R2 | R3 | EC50/μMa | lipid typologyb |

| 24 | C16H33 | H | CH3 | 750 | type 0 |

| 25 | C6H13 | H | H | 700 | undetermined |

| 26 | C12H25 | H | H | 20 | type 0 |

| 27 | C16H33 | H | H | 60 | type 0 |

A standard error of ±10% should be applied when interpreting these data.

Lipid typologies were determined by polarizing optical microscopy; those in italics were deduced because the typology of structurally similar compounds is known; some typologies were undetermined because the solubility of the compounds in aqueous solution was too low.

Table 3.

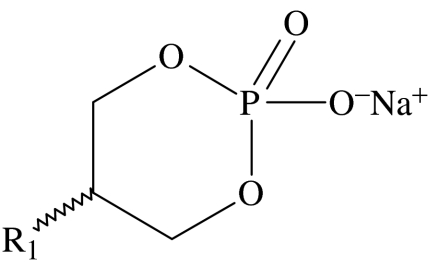

Structure, cytotoxicity, lipid typology and CMC of lysophospholipid analogues with heterocyclic headgroups. (Definitions of terms a and b are the same as given in table 2.)

heterocyclic headgroup general structure

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound number | R1 | EC50 μM | lipid typologyb | CMC/μMa |

| 28 | C12H25 | 287±21 | type I | 83 |

| 29 | C14H29 | 73.4±47 | type I | 14 |

| 30 | C16H33 | 43.4±37 | type I | 3.2 |

| 31 | C18H37 | 12.6±7.4 | type I | 0.6 |

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound number | X | Y | Z | R1 | R2 | EC50 μM | lipid typologyb | CMC μMa |

| 32 | O | O | CH2 | Me | C16H33 | 19.7±1.3 | type I | |

| 33 | NH | NH | CH2 | Me | C16H33 | 4.5±2.1 | type I | |

| 34 | O | NH | CH2 | Me | C16H33 | 2.8±1.2 | type I | |

| 35 | O | O | CMe2 | H | C14H29 | 20±10 | type I | |

| 36 | O | O | CMe2 | H | C16H33 | 16.5±8.5 | type I | 40 |

| 37 | O | O | CMe2 | H | C18H37 | 19.7±1.3 | type I | |

| 38 | O | O | CMe2 | H | oleyl | 6.67±2.7 | type I | 100 |

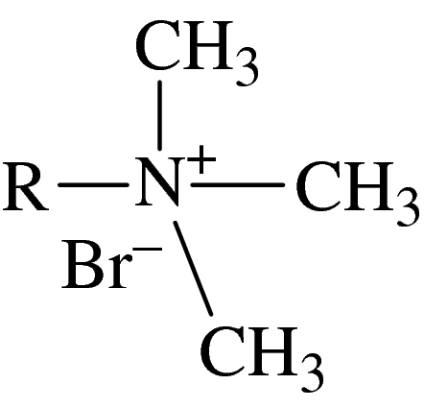

Table 4.

Structure, cytotoxicity, lipid typology and CMC of classic type I amphiphiles. (Definitions of terms a and b are the same as given in table 2.)

trimethylammonium series

|

octaethylene glycol series R-(OCH2CH2)8OH | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound number | headgroup | R | ED50/μM | lipid typologyb | CMC/μMa |

| 39 | trimethylammonium | C12H25 | 4.75±2.9 | type I | 1.00×104 |

| 40 | trimethylammonium | C14H29 | 3.56±2.1 | type I | 3.20×103 |

| 41 | trimethylammonium | C16H33 | 1.9±1.0 | type I | 1000 |

| 42 | octaethylene glycol | C10H21 | 47.5±24 | type I | 560 |

| 43 | octaethylene glycol | C12H25 | 22.6±13 | type I | 79 |

| 44 | octaethylene glycol | C14H29 | 7.25±3.4 | type I | 13 |

| 45 | octaethylene glycol | C16H33 | 4.51±2.6 | type I | 5.6 |

| 46 | octaethylene glycol | C18H37 | 3.39±2.0 | type I | 4 |

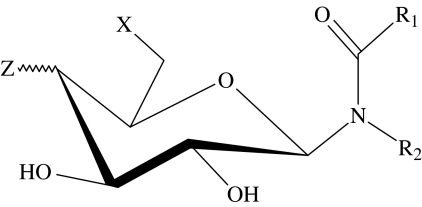

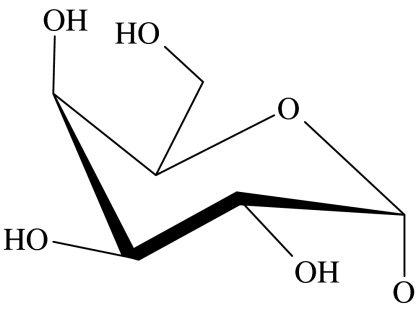

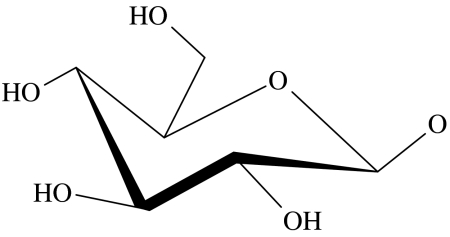

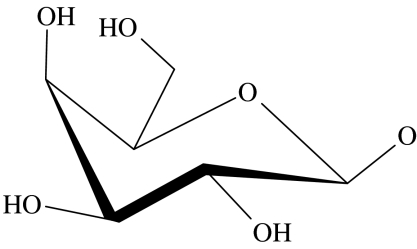

Table 5.

Structure, cytotoxicity and lipid typology of glycolipid compounds. (Definitions of terms a and b are the same as given in table 2.)

glycolipid general structure

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound number | X | Z | R1 | R2 | ED50/μMa | lipid typologyb |

| 47 | OH | OH(eq) | C7H15 | C8H17 | 20 | type 0 |

| 48 | OH | OH(eq) | C9H19 | C4H9 | 70 | type 0 |

| 49 | OH | OH(eq) | C15H31 | C4H9 | 22 | type 0 |

| 50 | OH | OH(eq) | C17H35 | C8H17 | 25 | type II |

| 51 | OH | OH(ax) | C17H35 | C8H17 | 68 | type II |

| 52 |  |

OH(eq) | C17H35 | C8H17 | 49 | type 0 |

| 53 | OH |  |

C17H35 | C8H17 | 55 | type 0 |

| 54 | OH |  |

C17H35 | C8H17 | 58 | type 0 |

| 55 | NH2 | OH(eq) | C17H35 | C8H17 | 8 | type 0 |

2.1 Cytotoxicity assay protocol

ED50 values were determined on the HL-60 cell line. HL-60 cells were cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 in RPMI medium with Glutamax-1 and HEPES (25 mM) supplemented with 10% foetal calf serum and 5% antibiotic–antimiotic solution (10 000 units ml−1 penicillin G sodium, 10 000 μg ml−1 streptomycin sulphate and 25 μg ml−1 amphotericin B as Fungizone in 0.85% saline). Live cell counts were performed using trypan blue staining.

Cytotoxicity was determined using the MTT assay (Marks et al. 1992) or by thymidine incorporation, compounds (14–27) as previously reported (McGuigan et al. 1994). For the MTT assay, compounds were dissolved into 11 mM stock solutions in ethanol or culture medium depending on solubility. These solutions were further diluted with culture medium to give 1, 5, 10, 50 and 100 μM solutions. Cells were seeded at 6×104 per well in 100 μl of medium and compound solutions were added in 10 μl aliquots. Cultures were incubated at 37°C for 96 hours, MTT was added to each well and plates were incubated for a further 4 hours; 100 μl of isopropanol acidified with 0.04 M HCl was added to dissolve the formazan product and the absorbance of each well was measured using a Titertek Multiscan R plus 96-well plate reader at 492 nm. Assays were conducted in triplicate and the ED50 was determined from plots of average cell number against amphiphile concentration.

2.2 Lyotropic phase studies

The morphology of the lyotropic liquid crystalline phases formed by amphiphiles and lipid analogues was determined using an Olympus BH-2 polarizing optical microscope equipped with a Linkham Scientific Instruments THM600 hot stage. The accuracy of the temperature of the hot stage was ±0.2°C. Phases were assigned by their characteristic optical textures (Hyde 2002). Two techniques were employed to identify phases, depending on the quantity of material available. For compounds only available in small amounts, contact preparations were used to qualitatively map the phase diagram (Hyde et al. 1954). For compounds that were available in larger amounts, binary mixtures were prepared and the phase diagram was mapped quantitatively. In the contact preparation technique, a small amount of material was melted on a microscope slide and covered by a cover-slip, which was gently pressed to squash the material into a thin film. After cooling the sample to room temperature, water was added which on coming in contact with the sample diffuses into it establishing a concentration gradient. Phases occurring at different degrees of hydration could be observed as successive bands from the external edge of the sample inwards. By changing the temperature of the sample, it was possible to observe temperature-induced changes in phase behaviour across the range of hydration. Phase diagrams were prepared from calculated compositions of lipid and water. Samples were thoroughly mixed and heated between a microscope slide and cover-slip.

2.3 Critical micelle concentration determinations

Critical micelle concentrations (CMCs) were determined in pure water from surface tension measurements using a CSC-Du Nouy Precision tensiometer 70535 (CSC Scientific Company, Inc.) fitted with a custom-made glass heating jacket. Solutions of the lipid were prepared in pure water and approximately 25 ml of each solution was poured into the heating jacket and allowed to equilibrate to 37±0.5°C. Surface tension measurements and CMC determinations were made using a standard method (Sharma et al. 2003).

3. Results

3.1 Evaluation of phosphoramide phospholipid analogues

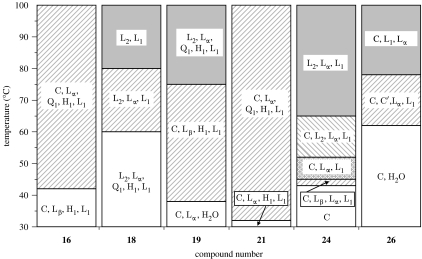

Most of the phosphoramide analogues (14–27) prepared show significant cytotoxicity towards the HL-60 cell line (table 2). The lyotropic liquid crystalline phase behaviour, obtained from penetration studies, of a representative selection of these compounds is shown in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Lyotropic liquid crystal contact preparations of phosphoramide phospholipid analogues, where L1, micellar solution; L2, inverse micellar solution; I1, micellar cubic phase; H1, hexagonal phase; HII, inverse hexagonal phase; Q1/Q2, cubic phases; Lα, fluid lamellar phase; Lβ, solid lamellar phase; C′, hydrated crystal and C, crystal. Divisions show the phases present within the temperature range.

3.1.1 Acyclic phosphoramides

Compound 16 is clearly a type I lipid, as evidenced by its phase behaviour being dominated by a normal topology hexagonal phase, which is stable up to 42°C. Compounds 15 and 17 are also type I lipids, since they are close homologues of compound 16. It is not possible to classify compound 14 as it showed no liquid crystal properties at, or above, room temperature. This is most probably due to its high solubility; however it has all the characteristics of a type I amphiphile. Within experimental error, the ED50 decreases monotonically on ascending the series 14–17. However the rate of decrease in the ED50 slows significantly for the higher homologues, with a minimum in ED50 occurring at compound 16. The alkyl chain length at this minimum is 16 carbon units, a value consistent with earlier observations (Andreesen et al. 1978; Vogler et al. 1993; Wieder et al. 1999). This behaviour, which is characteristic of amphiphilic cytotoxic compounds, is consistent with the predictions from equation (1.3) and illustrates the competition between the type I characteristics of the amphiphile and the hydrophobic effect-driven partitioning of the amphiphile. Changing the hydrocarbon chain from octadecyl (17) to oleyl (18) gives a small change in activity, which is probably insignificant within error. Compounds 17 and 19 are both type I lipids as shown by optical microscopy (see figure 2). Although both compounds are close homologues, at least in terms of hydrophobicity, the increase in headgroup size on going from a methyl to an ethyl substituent on the phosphate triester headgroup suggests that compound 19 might be expected to be the more active. In view of the proximity of this substitution site to the polar–apolar interface, it might be expected that there would be a big difference in the activity between compounds 17 and 19. The cytotoxicity data do indeed show a dramatic difference between the two compounds, with compound 19 having an ED50 that is nearly an order of magnitude lower than compound 17. Compounds 17, 21 and 22 provide an interesting test of the hypothesis. In this homologous series, the hydrophobic part of the amphiphile has the same number of carbon atoms, but while in compound 17 all 18 carbon atoms are part of a single alkyl chain, compounds 21 and 22 have two alkyl chains. All the three homologues are type I amphiphiles, as highlighted by the phase behaviour of the representative compound 21. On the basis of the rules of thumb outlined in figure 1, it is predicted that compound 21 should exhibit the highest activity (lowest ED50). This is because the propyl substituent on the phosphoramide nitrogen is close to the polar–apolar interface and leads to an amphiphile that has a larger headgroup cross section than the other two members of this series. In addition, the shorter alkyl chain means that this amphiphile is more effective at reducing stored elastic energy than compound 17. These predictions are in agreement with the experimental observations. A similar argument would suggest that compound 20 should be more active than compound 15 and this is supported by the data.

Compounds 20–22 are difficult to assess as type I lipids; from a structural point of view it is difficult to determine the effect of a second alkyl chain. Classically, two long alkyl chains will be type 0 if saturated and type II if unsaturated. However, starting with a single alkyl chain and then increasing the length of a second alkyl chain, from 1 to 10 carbon units, a situation arises where firstly the short chain increases the headgroup volume and then at some critical length it switches to the alkyl chain region increasing the hydrocarbon volume, as demonstrated for a series of quaternary ammonium amphiphiles (Hertel & Hoffmann 1989). Behaviour in the region of six carbon units is hard to predict, fewer than six carbon units certainly contribute to the headgroup region and thus compound 21 is type I as confirmed by phase studies. Compound 22 has a second alkyl chain of six units and it is consequently harder to assign as type I. Critically, the second alkyl chain increases potency; compound 23, which lacks the hexyl chain, is much less active than compound 22, but whether or not the increase in activity is due to increased type I properties or increased partitioning is unclear. Compound 20 illustrates that hydrophobicity is not key to determining activity since compounds 20 and 23 are likely to have very similar hydrophobicity but have very different activities.

3.1.2 Cyclic phosphoramides

Compounds 24–27 are all type 0 amphiphiles. The lack of a hydrated crystal phase in compound 24 (R3=CH3) compared with compound 26 (R3=H) suggests that hydrogen bonding plays a role in the aggregation behaviour of compound 26, a factor that should be taken into account when considering the ED50 of these compounds.

When the cytotoxicity of these compounds is examined (table 2), the least active compound is the hexyl analogue 25. This is unsurprising, as is the case for compound 14; the short alkyl chain reduces the need for partitioning into the membrane and thus the delivery of the active compound into the cell is hindered.

Compound 26 is a type 0 lipid, confirmed by phase studies and owing to its structural similarity compound 27 will also be type 0. Both these compounds show considerable activity, which is intriguing when compared with the less active compound 24. Clearly this change in activity is due to the inclusion of a methyl group at R3 and consequently the role of hydrogen bonding and hydration when present in a membrane becomes important. Using the lateral pressure profile, it is quite clear why this is the case: if the net stress in area γ is lowered, then the desire for type II behaviour increases. Hydrogen bonding increases the hydration in this region and thus increases the effective headgroup volume making the compounds 26 and 27 more type I than compound 24, agreeing with the prediction that more type I lipids will be more potent.

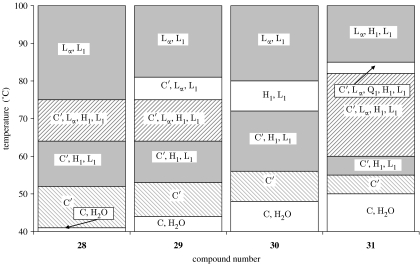

3.2 Evaluation of ALP analogues with heterocyclic headgroups

The lysophospholipids with heterocyclic headgroups (table 3) were problematic to assess by optical microscopy due to miscibility problems. An assessment of lipid typology is shown in figure 3. Compounds 28–31 were evaluated as sodium salts and were all shown to be type I lipids on the basis of the presence of a stable hexagonal phase in all the preparations. Compounds 32–38 were more difficult to assign due to low solubility, but because they are lysophosphatidylcholine analogues it is not unreasonable to expect them to be type I amphiphiles.

Figure 3.

Lyotropic liquid crystal contact preparations of ALP analogues with heterocyclic headgroups. Definitions of terms are the same as given legend of figure 2.

Compounds 28–31, the 2-hydroxy-1,3 dioxa-2-phosphacyclohexane-2-oxide analogues (table 3), show a clear relationship of increasing activity with chain length, with the octadecyl analogue (31) exhibiting the highest activity. This increase in activity with chain length is consistent with the qualitative trends predicted from equation (1.2), reflecting an increase in the partitioning of more hydrophobic, longer chain length compounds into the membranes. The series of homologues 32, 33 and 34 all have the same length of alkyl chain but differ in the nature of the heteroatoms in their headgroups. On the basis of the criteria outlined earlier, it is predicted that 33 should be the most active of this set, owing to the overall larger size of the headgroup, while 32, with the smallest headgroup, should be the least active. These predictions are in reasonable agreement with the experimental observations, which show that 33 and 34 have broadly similar activities, both of which are higher than 32).

The series of compounds 35, 36 and 37 are predicted to exhibit an increase in activity as the chain length increases from 14 to 18; however, it is not possible to differentiate between the activities of these homologues within the resolution of the experiment. The only observation for this group of amphiphiles that does not support the predictions stemming from our hypothesis is the comparison of the activities of compounds 37 and 38, for which it would be expected that the oleoyl homologue should be the less active of the two. Experimentally, it is observed that in fact homologue 38 has the higher activity.

3.3 Evaluation of classic type I amphiphiles

Two series of classic type I amphiphiles, namely the trimethylammonium bromide amphiphiles (39–41) and the octaethylene glycol amphiphiles (44–48; table 4), were also studied to test our hypothesis. The phase behaviour of the octaethylene glycol amphiphiles is well documented (Mitchell et al. 1983), as is the phase behaviour of the alkyltrimethyl ammonium bromide series (Hertel & Hoffmann 1988). It is noted that apart from their amphiphilic characteristics, these compounds bear no obvious chemical relationships to the ALP and APC compounds, but still exhibit the same patterns of cytotoxicity. Firstly, there is the increase in cytotoxicity with increasing chain length, as seen in compounds 39, 40 and 41, and more dramatically in the series 42–44, where the homologue with the octadecyl chain (46) is the most active.

3.4 Evaluation of the glycolipid analogues

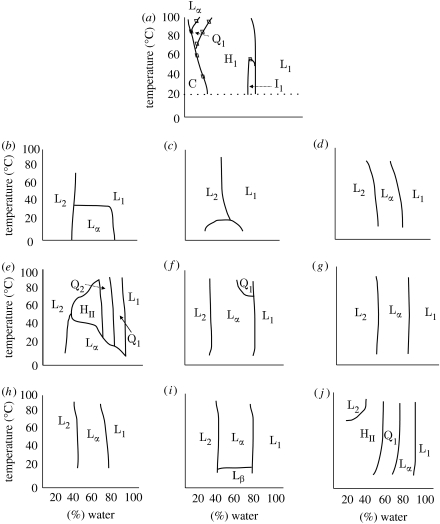

Table 5 shows a series of glycolipid compounds that provide a challenging test to our hypothesis. Clearly in chemical terms, these materials differ substantially from the lipid analogues described earlier. However, investigation of their phase behaviour suggests that they are largely type 0 lipids, as confirmed by phase studies (figure 4). We note that compounds 50 and 51 are type II amphiphiles because their phase behaviour is dominated by inverse topology phases. Applying the qualitative rules we outlined earlier to homologues 48 and 49 would lead to the prediction that 49 should be the more active of the two in view of its longer hydrocarbon chain. This is consistent with the experimental data. Similarly, for the pair 47 and 50 it would be expected that 47 would be the more active, because the shorter chains would create a packing void when mixed with the longer chain lipids found in membranes. As a consequence 47 would act to reduce the stored elastic energy when compared with 50. The experimental data are consistent with this prediction.

Figure 4.

Lyotropic liquid crystal phase diagrams of glycolipid analogues. Definitions of terms are the same as given in figure legend 2. (a) HDPC (2), (b) compound 47, (c) compound 48, (d) compound 49, (e) compound 50, (f) compound 51, (g) compound 52, (h) compound 53, (i) compound 54, (j) compound 55.

Comparison of compounds 50 and 52 illustrates the effect of an additional sugar moiety in the headgroup. We would expect that 52 should be the more active of the two on the basis of its larger headgroup. This is the opposite to what is observed experimentally, which may be due to the increased solubility of 52 compared with 51 counteracting its effect on the stored elastic energy. This is supported by a comparison of 52 and 53. Both these homologues have two carbohydrate moieties in their headgroup region; so they would be expected to have comparable solubility. However 53 would be expected to be the less active on account of the linear nature of the headgroup, and consequently smaller headgroup cross section than 52. The cytotoxicity data are in agreement with this prediction.

Finally for this complex series, we draw comparisons between the activities of 47 and 55; 52 and 54; 53 and 54; and 48 and 49. We would predict that 47 should be the more active of the two, since the primary amine group would be expected to become protonated under physiological conditions, thereby resulting in strong type I behaviour due to electrostatic repulsions between headgroups. The ED50 of 55 is 8 μM, compared with 20 μM for 47, consistent with our predictions. Compound 52 should be more active than 54 because the skewed headgroup has a wider cross-sectional area than the stacked system in 54, but the overall solubility is unchanged. The ED50 of 52 is 49 μM compared with 58 μM for 54; within experimental error there is no difference. Comparing compounds 53 and 54, we would predict very little change in activity because the structural change from an equatorial (53) to axial (54) hydroxyl group occurs at a distance from the interface. This may have a minor effect on headgroup packing, but hydration is unlikely to change significantly. In the cases of compounds 48 and 49, 49 should be the more active because it has a longer hydrocarbon chain than 48 and hence it partitions more effectively into the membrane. This accords with our observations.

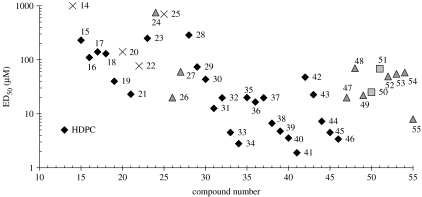

Figure 5 shows cytotoxicity data for all the compounds evaluated above, compared with their liquid crystal typology. It is clear from figure 5 that the most active compounds are all type I lipids, which include HDPC. In addition some of the compounds evaluated in this study are of greater potency than HDPC and potentially represent new classes of chemotherapeutic compounds.

Figure 5.

A comparison of ED50 against lipid typology for phosphoramide compounds (14–27), lysophospholipids with heterocyclic headgroups (28–38), classic type I amphiphiles (39–46) and glycolipid analogues (47–55). Diamonds, type I; triangles, type 0; crosses, undetermined; squares, type II.

4. Discussion

A major problem in interpreting the structure activity data of ALP and APC analogues is the role of the lysis in the mechanism of action. Generally, with respect to the ALP and APC analogues, it is accepted that lysis is a potential mechanism of action but only at higher concentration and this is supported by some experimental evidence (Dive et al. 1991). Recently Busto et al. (2007) concluded that in the case of ET-18-OMe lysis is not a probable mechanism of cytotoxicity due to the poor ability of ET-18-OMe to breakdown vesicles in vitro.

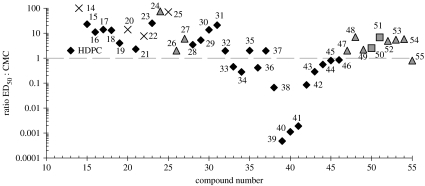

The viability of lysis as a mechanism is dependent on the concentration of the detergent molecules. Below the CMC, amphiphile monomers do not aggregate in solution, instead individual monomers are soluble in the aqueous environment. In the presence of a cellular membrane and below the CMC, the hydrophobic effect will force the amphiphiles into the membrane, creating equilibrium between the membrane and monomers in solution. At concentrations above or around the CMC, the same equilibrium exists, but this time it is between the monomers in the membrane and aggregates in the aqueous solution; thus there is a mechanism for solubilizing cellular components in the extracellular environment. If the ED50 is significantly below the CMC, then we believe that lysis is not the dominant mechanism of action. In practice it is easier to consider the ratio of the ED50 to the CMC as a guide. At values greater than 1, there are likely to be aggregates of the active material present in the extracellular environment. Such aggregates could cause cell death by both lysis and curvature elastic stress modulation.

Experimental values of the CMC are given alongside the structures, where insufficient material was available to perform surface tension measurements; literature values have been employed to provide estimates. From the literature we have found glycolipid analogues with CMCs in the range of 1×10−4 M to 1×10−6 M (Takeoka et al. 1998; Augusto et al. 2002). Since the chain lengths in this study are relatively long, we use an intermediate value of 1×10−5 M for compounds 47–55. The phosphoramide analogues (14–27) are analogues of HDPC (CMC=8×10−6 M; Kotting et al. 1992) and are likely to have CMCs of a similar order of magnitude; however, we conservatively use 1×10−5 M for all these compounds. Figure 6 shows the corresponding plot of compound versus the ratio of ED50:CMC. It is immediately of note that all the compounds active below their CMC are type I lipids, the most potent modulators of the stored elastic stress. It seems very unlikely that these compounds could be active exclusively through lysis, a view that is supported by our observations in the laboratory, where cells treated with low concentrations of active compound remained intact; at higher concentrations cells were homogenized by lysis.

Figure 6.

Plot of the ratio of the ED50:CMC for phosphoramide compounds (14–27), lysophospholipids with heterocyclic headgroups (28–38), classic type I amphiphiles (39–46) and glycolipid analogues (47–55). Compounds with a ratio of greater than 1 probably have a lytic effect on cellular membranes. Diamonds, type I; triangles, type 0; crosses, undetermined; squares, type II.

In our studies the ED50 of HDPC ranges from 2.5 to 6.5×10−6 M (see figure 5). The CMC of HDPC from the literature is 2.5–3×10−6 M (Rakotomanga et al. 2004) and 8×10−6 M (Kotting et al. 1992), thus for HDPC the ratio ED50:CMC falls in the range of 1–3 and a lytic mechanism cannot be completely ignored (see figure 6). Our most active compounds (39, 49, 41) are more potent than HDPC and active well below their CMC; potentially, these compounds offer more effective cancer treatments.

Most of the cytotoxic analogues of ALP and APC compounds in the literature follow structure activity trends that agree with the predictions of our simple hypothesis. This is further complemented by the data that we have presented of our own studies on systems. There are a few notable exceptions in the literature which are cytotoxic but are not easily explained by our hypothesis, using the current limited information on their aggregation properties. These exceptions are the plasmanyl-(N-acyl)-ethanolamines (Kara et al. 1986), a series of naturally occurring compounds with in vitro and in vivo antitumour activities. Structurally these compounds are dialkylglycerophosphoethanolamines with one of the ethanolamine hydrogens replaced by the moiety COC15H31. Effectively, this gives a compound with three alkyl chains, which is likely to exhibit type II lipid behaviour due to the large hydrocarbon region; however, proper lyotropic liquid crystal phase studies will need to be carried out before any firm conclusion is made. The other apparent exception to the hypothesis proposed by us is the compound erucylphosphocholine (EPC). EPC has been studied extensively (Kotting et al. 1992; Jendrossek et al. 2002, 2003; Jendrossek & Handrick 2003) and shows greater (Zeisig et al. 1993) or comparable potency (Kotting et al. 1992) to HDPC. The erucyl chain is the cis-13-docosenol derivative; it is probably a type 0 lipid, since it forms lamellar structures rather than micelles (Kotting et al. 1992). Currently, there are no detailed phase studies to confirm this; regardless though, it is curious that this single long-chain derivative is active when many studies have concluded that the chain length of 16–18 carbon units gives the highest activity. Of note are the observations that EPC is more active than HDPC in Jurkat, Raji and Ramos cell lines but less active in HL-60 cells (Konstantinov et al. 1998b). Also EPC is consistently more active than HDPC in a series of brain cell lines (Jendrossek et al. 2002) as are a series of other long chain monounsaturated analogues. In our theory the bilayer thickness will change the optimum chain length for highest activity as modelled by the local molecular environment portion of equation (1.3). This may explain why EPC is more active than HDPC in some cell lines and vice versa. If our theory is correct we would predict the saturated analogue of EPC (docosonyl PC) to be more active than EPC in cell lines where EPC is more active than HDPC; currently, there are no data for this analogue in the literature.

The case of EPC illustrates the complexity of the relationship between structure and cytotoxicity, with many studies reporting different orders of potency for EPC and HDPC. Many of these problems could be eliminated by adopting a standard experimental protocol, as we have done after experiencing conflicting data in the literature and problems with our own early work. We suggest using the MTT assay to determine the ED50, but in addition the ED50 of every set of compounds should be compared with the ED50 of HDPC, measured in the same experiments as a reference compound, shown in equation (4.1).

| (4.1) |

where n is the number of seed cells; ED50cmp is ED50 of the active compound and ED50ref is the ED50 of HDPC measured at the same time as the active compound.

The value ED50 (normalized) allows the ED50 from different determinations of cytotoxicity to be compared with each other. Furthermore, since partitioning into the cell membrane is a critical part of the mechanism of action for these compounds, normalizing with the number of cells is a critical necessity for quantitative treatments.

We have proposed that the enzyme CCT is the probable cellular target of ALP and APC analogues. Historically, the mechanism of CCT regulation by the composition of lipid membranes has been a matter of debate. An initial model proposed negative membrane surface charge to be the activator of CCT (Cornell 1991a) with the physical properties of biomembranes playing a potential role (Cornell 1991b); however, these early studies failed to explain the activation or deactivation of CCT by uncharged or electrostatically neutral, zwitterionic lipids. Attard et al. (2000) proposed that membrane-free energy, in particular stored curvature elastic stress, regulated CCT translocation and hence activity. This was demonstrated with the zwitterionic lipids dioleoyl phosphoethanolamine (DOPE), a CCT activator, and lyso-myristoyl phosphocholine (MPC), a CCT deactivator. Davies et al. (2001) confirmed that CCT deactivation by lyso-oleoyl phosphocholine (OPC) and lyso-oleoyl phosphoethanolamine (OPE) and CCT activation by DOPE correlate with membrane stored elastic energy. OPC, MPC and OPE are type I lipids and ALP compounds, which all deactivate CCT in vitro. Other studies have shown that CCT activity is decreased by the type I lipids hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (41) (Sohal & Cornell 1990) and octaethylene glycol monohexadecyl ether (45) (Attard et al. 2000), providing further evidence to support our hypothesis that it is the type I lipid properties of ALP and APC compounds which confer their cytotoxicity.

5. Conclusions

Our analysis of the cytotoxicity data of amphiphilic ALP and APC analogues has shown that the trends in activity in relation to the various moieties of these amphiphiles are consistent with the hypothesis that their primary effect is a decrease in the stored curvature elastic energy of cellular membranes. This suggests that the primary targets of amphiphilic antineoplastic agents are most likely to be proteins whose activity is modulated by the composition of the membranes with which they associate. The most probable candidate appears to be CCT, which from in vitro studies has been shown to be strongly modulated by type I amphiphiles. Our results and analysis provide a new rationale for the design of antineoplastic drugs that do not interact with DNA.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Leverhulme Trust, the Royal Society and the Medical Research Council, UK. The authors would like to thank R.H. Templer, Imperial College London, for many discussions on membrane curvature elastic stress and protein regulation, W.P. Blackaby, J.W. Wang, A. Mackenzie and W. S. Smith for the synthesis and evaluation of antineoplastic compounds, and C McGuigan, University of Wales Cardiff, for collaboration on the ALP analogues and glycolipid analogues.

References

- Andreesen R, Modolell M, Weltzien H.U, Eibl H, Common H.H, Loehr G.W, Munder P.G. Selective destruction of human leukemic cells by alkyl-lysophospholipids. Cancer Res. 1978;38:3894–3899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attard G.S, Templer R.H, Smith W.S, Hunt A.N, Jackowski S. Modulation of CTP: phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase by membrane curvature elastic stress. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:9032–9036. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160260697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augusto L.A, Li J, Synguelakis M, Johansson J, Chaby R. Structural basis for interactions between lung surfactant protein C and bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:23 484–23 492. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111925200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkovic D. Cytotoxic etherphospholipid analogues. Gen. Pharmacol. 1998;31:511–517. doi: 10.1016/S0306-3623(98)00081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackaby W.P. University of Wales; Southampton, UK: 1997. The synthesis, biological and physical evaluation of glycolipid derivatives. [Google Scholar]

- Boggs K.P, Rock C.O, Jackowski S. Lysophosphatidylcholine and 1-O-octadecyl-2-O-methyl-rac-glycero-3-phosphocholine inhibit the CDP-choline pathway of phosphatidylcholine synthesis at the CTP: phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase step. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:7757–7764. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boggs K, Rock C.O, Jackowski S. The antiproliferative effect of hexadecylphosphocholine toward HL60 cells is prevented by exogenous lysophosphatidylcholine. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998;1389:1–12. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2760(97)00145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachwitz H, Vollgraf C. Analogs of alkyllysophospholipids: chemistry, effects on the molecular level and their consequences for normal and malignant cells. Pharmacol. Ther. 1995;66:39–82. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(95)00001-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachwitz H, Langen P, Otto A, Schildt J. Halolipids. III. Alkyl glyceryl ether analogs. J. Prakt. Chem. 1979;321:775–786. doi: 10.1002/prac.19793210509. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brachwitz H, Langen P, Hintsche R, Schildt J. Halo lipids. V. Synthesis, nuclear magnetic resonance spectra and cytostatic properties of halo analogs of alkyllysophospholipids. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 1982;31:33–52. doi: 10.1016/0009-3084(82)90017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachwitz H, Langen P, Schildt J. Halo lipids. 7. Synthesis of rac 1-chloro-1-deoxy-2-O-hexadecylglycero-3-phosphocholine. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 1984;34:355–362. doi: 10.1016/0009-3084(84)90009-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brachwitz H, Langen P, Arndt D, Fichtner I. Cytostatic activity of synthetic O-alkylglycerolipids. Lipids. 1987;22:897–903. doi: 10.1007/BF02535551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busto J.V, Sot J, Goni F.M, Mollinedo F, Alonso A. Surface-active properties of the antitumour ether lipid 1-O-octadecyl-2-O-methyl-rac-glycero-3-phosphocholine (edelfosine) Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1768:1855–1860. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornell R.B. Regulation of CTP: phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase by lipids. 1. Negative surface charge dependence for activation. Biochemistry. 1991a;30:5873–5880. doi: 10.1021/bi00238a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornell R.B. Regulation of CTP: phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase by lipids. 2. Surface curvature, acyl chain length, and lipid-phase dependence for activation. Biochemistry. 1991b;30:5881–5888. doi: 10.1021/bi00238a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danhauser S, Berdel W.E, Schick H.D, Fromm M, Reichert A, Fink U, Busch R, Eibl H, Rastetter J. Structure-cytotoxicity studies on alkyl lysophospholipids and some analogs in leukemic blasts of human origin in vitro. Lipids. 1987;22:911–915. doi: 10.1007/BF02535553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies S.M, Epand R.M, Kraayenhof R, Cornell R.B. Regulation of CTP: phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase activity by the physical properties of lipid membranes: an important role for stored curvature strain energy. Biochemistry. 2001;40:10 522–10 531. doi: 10.1021/bi010904c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick D.L, Lawrence D.S. Physicochemical behavior of cytotoxic ether lipids. Biochemistry. 1992;31:8252–8257. doi: 10.1021/bi00150a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dive C, Watson J.V, Workman P. Multiparametric flow cytometry of the modulation of tumor cell membrane permeability by developmental antitumor ether lipid SRI 62-834 in EMT6 mouse mammary tumor and HL-60 human promyelocytic leukemia cells. Cancer Res. 1991;51:799–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromm M, Berdel W.E, Schick H.D, Fink U, Pahlke W, Bicker U, Reichert A, Rastetter J. Antineoplastic activity of the thioether lysophospholipid derivative BM 41.440 in vitro. Lipids. 1987;22:916–918. doi: 10.1007/BF02535554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geilen C.C, Haase A, Wieder T, Arndt D, Zeisig R, Reutter W. Phospholipid analogs: side chain- and polar head group-dependent effects on phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis. J. Lipid Res. 1994;35:625–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geilen C.C, Wieder T, Orfanos C.E. Phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis as a target for phospholipid analogs. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1996;416:333–336. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-0179-8_53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanauske A.R, Degen D, Marshall M.H, Hilsenbeck S.G, McPhillips J.J, Von Hoff D.D. Preclinical activity of ilmofosine against human tumor colony forming units in vitro. Anti-Cancer Drugs. 1992;3:43–46. doi: 10.1097/00001813-199202000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfrich W. Elastic properties of lipid bilayers: theory and possible experiments. Z. Naturforsch. [C] 1973;28:693–703. doi: 10.1515/znc-1973-11-1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertel G, Hoffmann H. Lyotropic nematic phases of double-chain surfactants. Prog. Colloid Polym. Sci. 1988;76:123–131. doi: 10.1007/BFb0114182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hertel G, Hoffmann H. New lyotropic nematics of double chain surfactants. Liq. Crystals. 1989;5:1883–1898. doi: 10.1080/02678298908045696. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman D.R, Stanley J.D, Berchtold R, Snyder F. Cytotoxicity of ether-linked phytanyl phospholipid analogs and related derivatives in human HL-60 leukemia cells and polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Res. Commun. Chem. Pathol. Pharmacol. 1984;44:293–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honma Y, Kasukabe T, Okabe-Kado J, Hozumi M, Tsushima S, Nomura H. Antileukemic effect of alkyl phospholipids. I. Inhibition of proliferation and induction of differentiation of cultured myeloid leukemia cells by alkyl ethyleneglycophospholipids. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 1983;11:73–76. doi: 10.1007/BF00254248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honma Y, Kasukabe T, Hozumi M, Akimoto H, Nomura H. Induction of differentiation of human myeloid leukemia HL-60 cells by novel nonphosphorus alkyl ether lipids. Lipids. 1991;26:1445–1449. doi: 10.1007/BF02536583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houlihan W.J, Lee M.L, Munder P.G, Nemecek G.M, Handley D.A, Winslow C.M, Happy J, Jaeggi C. Antitumor activity of SRI 62-834, a cyclic ether analog of ET-18-OCH3. Lipids. 1987;22:884–890. doi: 10.1007/BF02535549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde A.J, Langbridge D.M, Lawrence A.S.C. Soap, water and amphiphile systems. Discuss. Faraday Soc. 1954;18:239–257. doi: 10.1039/df9541800239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde S.T. Identification of lyotropic liquid crystalline mesophases. In: Holmberg K, editor. Handbook of applied surface and colloid chemistry. John Wiley & Sons; Chichester, UK: 2002. pp. 299–332. [Google Scholar]

- Ishaq K.S, Capobianco M, Piantadosi C, Noseda A, Daniel L.W, Modest E.J. Synthesis and biological evaluation of ether-linked derivatives of phosphatidylinositol. Pharm. Res. 1989;6:216–224. doi: 10.1023/A:1015961416370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackowski S. Coordination of membrane phospholipid synthesis with the cell cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:3858–3867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackowski S. Cell cycle regulation of membrane phospholipid metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:20 219–20 222. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.33.20219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackowski, S. & Baburina, I. 2002 Lipid interaction with cytidylyltransferase regulates membrane synthesis. In Biophysical chemistry membranes and proteins. Special publication no. 283. Cambridge, UK: Royal Society of Chemistry.

- Jackowski S, Boggs K. Proceedings of the 7th International Congress on Phospholipids, Brussels, Belgium, September 1996. ACOS Press; Champaign, IL: 1998. Antineoplastic phospholipids inhibit phosphatidyl biosynthesis; pp. 30–44. [Google Scholar]

- Jamil H, Hatch G.M, Vance D.E. Evidence that binding of CTP: phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase to membranes in rat hepatocytes is modulated by the ratio of bilayer- to non-bilayer-forming lipids. Biochem. J. 1993;291:419–427. doi: 10.1042/bj2910419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jendrossek V, Handrick R. Membrane targeted anticancer drugs: potent inducers of apoptosis and putative radiosensitisers. Curr. Med. Chem. Anti-Cancer Agents. 2003;3:343–353. doi: 10.2174/1568011033482341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jendrossek V, Hammersen K, Erdlenbruch B, Kugler W, Kruegener R, Eibl H, Lakomek M. Structure–activity relationships of alkylphosphocholine derivatives: antineoplastic action on brain tumor cell lines in vitro. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2002;50:71–79. doi: 10.1007/s00280-002-0440-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jendrossek V, Mueller I, Eibl H, Belka C. Intracellular mediators of erucylphosphocholine-induced apoptosis. Oncogene. 2003;22:2621–2631. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Lopez J.M, Carrasco M.P, Segovia J.L, Marco C. Hexadecylphosphocholine inhibits phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis and the proliferation of HepG2 cells. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002;269:4649–4655. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kara J, Borovicka M, Liebl V, Smolikova J, Ubik K. A novel nontoxic alkyl-phospholipid with selective antitumor activity, plasmanyl-(N-acyl)-ethanolamine (PNAE), isolated from degenerating chick embryonal tissues and from an anticancer biopreparation cACPL. Neoplasma. 1986;33:187–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent C. CTP: phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1997;1348:79–90. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(97)00112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinov S.M, Eibl H, Berger M.R. Alkylphosphocholines induce apoptosis in HL-60 and U-937 leukemic cells. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 1998a;41:210–216. doi: 10.1007/s002800050730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinov S.M, Topashka-Ancheva M, Benner A, Berger M.R. Alkylphosphocholines: effects on human leukemic cell lines and normal bone marrow cells. Int. J. Cancer. 1998b;77:778–786. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19980831)77:5%3C778::AID-IJC18%3E3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotting J, Berger M.R, Unger C, Eibl H. Alkylphosphocholines: influence of structural variation on biodistribution at antineoplastically active concentrations. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 1992;30:105–112. doi: 10.1007/BF00686401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo I, Nojima S, Chang H.W, Yanoshita R, Hayashi H, Kondo E, Nomura H, Inoue K. Antitumor activity of synthetic alkylphospholipids with or without PAF activity. Lipids. 1987;22:862–867. doi: 10.1007/BF02535545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langen P, Brachwitz H, Schildt J. Inhibition of proliferation of Ehrlich ascites carcinoma cells in vitro and in vivo by halogeno analogues of long chain acyl- and alkylglycerols. Acta Biol. Med. Ger. 1979;38:965–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langen P, Maurer H.R, Brachwitz H, Eckert K, Veit A, Vollgraf C. Cytostatic effects of various alkyl phospholipid analogs on different cells in vitro. Anticancer Res. 1992;12:2109–2112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie A.N. University of Southampton; Southampton, UK: 1995. The synthesis of novel phospholipids. [Google Scholar]

- Marks D.C, Belov L, Davey M.W, Davey R.A, Kidman A.D. The MTT cell viability assay for cytotoxicity testing in multidrug-resistant human leukemic cells. Leuk. Res. 1992;16:1165–1173. doi: 10.1016/0145-2126(92)90114-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh D. Elastic curvature constants of lipid monolayers and bilayers. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2006;144:146–159. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuigan C, Wang Y, Riley P.A. Synthesis and biological evaluation of phosphate triester alkyl lysophospholipids (ALPs) as novel potential anti-neoplastic agents. Anti-Cancer Drug Des. 1994;9:539–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell D.J, Tiddy G.J.T, Waring L, Bostock T, McDonald M.P. Phase behavior of polyoxyethylene surfactants with water. Mesophase structures and partial miscibility (cloud points) J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1. 1983;79:975–1000. doi: 10.1039/f19837900975. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morris-Natschke S, Surles J.R, Daniel L.W, Berens M.E, Modest E.J, Piantadosi C. Synthesis of sulfur analogs of alkyl lysophospholipid and neoplastic cell growth inhibitory properties. J. Med. Chem. 1986;29:2114–2117. doi: 10.1021/jm00160a055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munder P.G. Antitumor activity of alkyllysophospholipids. Human Cancer Immunol. 1982;3:17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Noseda A, Berens M.E, Piantadosi C, Modest E.J. Neoplastic cell inhibition with new ether lipid analogs. Lipids. 1987;22:878–883. doi: 10.1007/BF02535548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Principe P, Braquet P. Advances in either phospholipids treatment of cancer. Crit. Rev. Oncol.-Hematol. 1995;18:155–178. doi: 10.1016/1040-8428(94)00118-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakotomanga M, Loiseau P.M, Saint-Pierre-Chazalet M. Hexadecylphosphocholine interaction with lipid monolayers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1661:212. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schick H.D, et al. Cytotoxic effects of ether lipids and derivatives in human nonneoplastic bone marrow cells and leukemic cells in vitro. Lipids. 1987;22:904–910. doi: 10.1007/BF02535552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seddon J.M. Structure of the inverted hexagonal (HII) phase, and non-lamellar phase transitions of lipids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1990;1031:1–69. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(90)90002-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma K.S, Rodgers C, Palepu R.M, Rakshit A.K. Studies of mixed surfactant solutions of cationic dimeric (gemini) surfactant with nonionic surfactant C12E6 in aqueous medium. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2003;268:482–488. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2003.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohal P.S, Cornell R.B. Sphingosine inhibits the activity of rat liver CTP: phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:11 746–11 750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeoka S, Sou K, Boettcher C, Fuhrhop J.-H, Tsuchida E. Physical properties and packing states of molecular assemblies of synthetic glycolipids in aqueous dispersions. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1998;94:2151–2158. doi: 10.1039/a800289d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tarnowski G.S, Mountain I.M, Stock C.C, Munder P.G, Weltzien H.U, Westphal O. Effect of lysolecithin and analogs on mouse ascites tumors. Cancer Res. 1978;38:339–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrecillas A, Aroca-Aguilar J.D, Aranda F.J, Gajate C, Mollinedo F, Corbalan-Garcia S, de Godos A, Gomez-Fernandez J.C. Effects of the anti-neoplastic agent ET-18-OCH3 and some analogs on the biophysical properties of model membranes. Int. J. Pharm. 2006;318:28–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger C, Fleer E.A, Kotting J, Neumuller W, Eibl H. Antitumoral activity of alkylphosphocholines and analogues in human leukemia cell lines. Prog. Exp. Tumor Res. 1992;34:25–32. doi: 10.1159/000420829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogler W.R, Olson A.C, Hajdu J, Shoji M, Raynor R, Kuo J.F. Structure–function relationships of alkyl-lysophospholipid analogs in selective antitumor activity. Lipids. 1993;28:511–516. doi: 10.1007/BF02536082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogler W.R, Shoji M, Hayzer D.J, Xie Y.P, Renshaw M. The effect of edelfosine on CTP: cholinephosphate cytidylyltransferase activity in leukemic cell lines. Leuk. Res. 1996;20:947–951. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2126(96)00070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan W.J. University of Southampton; Southampton, UK: 1997. Novel ether lipids as antineoplastic agents. [Google Scholar]

- Weber N, Benning H. Metabolism of ether glycolipids with potentially antineoplastic activity by Ehrlich ascites tumor cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1988;959:91–94. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(88)90153-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieder T, Orfanos C.E, Geilen C.C. Induction of ceramide-mediated apoptosis by the anticancer phospholipid analog, hexadecylphosphocholine. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:11 025–11 031. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.18.11025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieder T, Reutter W, Orfanos C.E, Geilen C.C. Mechanisms of action of phospholipid analogs as anticancer compounds. Prog. Lipid Res. 1999;38:249–259. doi: 10.1016/S0163-7827(99)00004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeisig R, Jungmann S, Arndt D, Schuett A, Nissen E. Antineoplastic activity in vitro of free and liposomal alkylphosphocholines. Anti-Cancer Drugs. 1993;4:57–64. doi: 10.1097/00001813-199302000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]