Abstract

Previous studies have emphasized that the adhesion strength between solid objects tends to increase as the characteristic size of the objects decreases and eventually saturates at the theoretical adhesion strength below a critical size scale. Here we show that the adhesion strength between two spheres or between a sphere and a solid half-space actually exhibits a peak value at an optimal size. This optimal size arises owing to a transition between surface- and bulk-dominated interaction regimes at the nanoscale.

Keywords: contact mechanics, intermolecular adhesion, size dependence, adhesion strength, nanoscale

1. Introduction

Intermolecular forces, although usually much weaker than interatomic forces, are known to play important roles in many physical properties such as melting point, vapour pressure, evaporation, viscosity and surface tension. Recent studies have shown that intermolecular forces also play a dominant role in the reversible adhesion mechanisms of gecko and many insects (Autumn et al. 2000, 2002; Arzt et al. 2003). The bottom surfaces of the toes of gecko are covered with scale-like structures called lamellae; each lamella is coated with hundreds of thousands of fibres called setae; each seta is approximately 110 μm long and further branches into hundreds of 200–500 nm nano-hairs called spatulae. This hairy structure of gecko represents a class of convergent evolution for dry adhesion. Among hundreds of animal species that have adopted similar hairy adhesion structures, gecko stands out in terms of its body weight and its extraordinary ability to manoeuvre on vertical walls and ceilings. Arzt et al. (2003) discussed an interesting correlation between the size of the smallest hairs of animals and their body weight: the heavier the animal, the smaller the hairs, and gecko's spatulae are the smallest. This size effect has stimulated a number of theoretical studies showing that the adhesion strength between solid objects generally tends to increase as the characteristic size of the objects is reduced and eventually saturates at the theoretical adhesion strength below a critical size (Persson 2003; Gao & Yao 2004; Gao et al. 2005; Tang et al. 2005). Gao & Yao (2004) showed that the adhesion strength can also be enhanced by optimizing the shape of the contact objects at any sizes, although shape-insensitive optimal adhesion can only be achieved at sufficiently small scales.

In addition to adhesion enhancement at small scales, a somewhat related concept is to achieve robust, flaw-tolerant adhesion by size reduction and hierarchical design (Gao et al. 2003; Gao & Chen 2005; Yao & Gao 2006, 2007). In general, crack-like flaws due to surface roughness or contaminants tend to magnify stresses at the edges of contact regions, and adhesion failure usually occurs via crack propagation along the contact interface. Under this circumstance, the load-carrying capacity of the interface is not fully used, since only a small amount of material near the contact edges is loaded near the theoretical adhesion strength while most of the interface is subjected to much smaller stress levels. In this regard, it has been shown that size reduction at the bottom scale followed by hierarchical design at larger scales can lead to homogeneous stress distribution at pull-off, thereby relieving stress concentration effects of random, uncontrollable flaws along the contact interface (Gao & Chen 2005; Yao & Gao 2006, 2007).

A common view shared by most of the existing studies is that the strength of intermolecular adhesion is a non-decreasing function as the size of the contacting objects is reduced. However, these studies have all made an implicit assumption that intermolecular adhesion can be described as an interaction between two adjacent surfaces. In the following, we show that this assumption is not valid if one of the contacting objects is a nanoparticle, in which case intermolecular adhesion can no longer be described as an interaction between two solid surfaces because the particle itself may become completely immersed in the interaction zone. In fact, we will show that intermolecular adhesion between two spheres or between a sphere and a solid half-space exhibits a peak value at an optimal size determined by a transition between surface- and bulk-dominated interaction regimes at the nanoscale.

The plan for the rest of this paper is as follows. The basic concept of conventional inter-surface force models is briefly reviewed in §2. This then sets the stage for discussions in §3 on the maximum strength for intermolecular adhesion between a sphere and a solid half-space at an optimal size. In §4, we generalize the analysis of §3 to adhesion between two spheres. In §5, we demonstrate that the adhesion strength between a hemisphere-ended cylinder and a solid half-space does exhibit a saturation in strength below a critical size, in agreement with conventional contact mechanics models, thereby showing that the phenomenon of maximum adhesion at an optimal size only arises if one of the contacting objects is a nanoparticle.

2. Inter-surface force model of intermolecular interaction

Intermolecular forces can be either attractive or repulsive. The most dominant attractive force is the van der Waals force that has an interaction energy inversely proportional to the sixth power of the intermolecular separation r, that is, Ua(r)∝r−6. In comparison with the attractive force, the repulsive force has a much shorter interaction range. A common description of the repulsive force is Ur(r)∝r−n, where n is an integer normally between 9 and 16. A common interaction potential between two molecules is the 6–12 Lennard-Jones (LJ) potential,

| (2.1) |

where A and B are constants.

Assuming the intermolecular potential is additive, the interaction potential between two solid objects can be obtained by integrating the LJ potential over the material domains. Calculations of this type were first made by de Boer (1936) and Hamaker (1937; e.g. Israelachvili 1992). For example, the interaction potential between a single isolated molecule at a distance D from a solid half-space is obtained by summing up the interactions between the isolated molecule and all molecules in the solid as

| (2.2) |

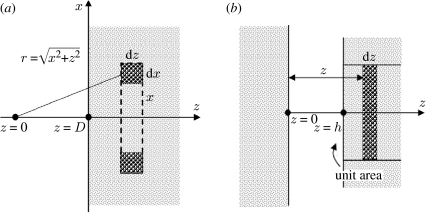

The derivation of the above equation is straightforward when one realizes that the number of molecules inside a circular ring with infinitesimal cross-sectional area dx dz and radius x is 2πρ1x dx dz, ρ1 being the molecular density in the solid (figure 1a). Based on this result, we can further calculate the interaction energy per unit area between two solid half-spaces with surfaces parallel to one another (figure 1b). Consider a thin sheet of molecules of thickness dz at a distance z from a solid half-space, as shown in figure 1b. According to equation (2.2), the interaction energy per unit area between this sheet and the solid half-space can be written as

| (2.3) |

where ρ2 is the molecular density in the second solid. With this result, the interaction energy between two solid half-spaces can be expressed as a function of their surface separation h as

| (2.4) |

The adhesive force per unit area, also referred to as the interaction stress, is given by

| (2.5) |

The sign of the interaction stress is chosen to be consistent with the sign convention of elasticity, that is, tension is positive. Denoting the equilibrium separation as z0 at which the interaction stress vanishes, equation (2.5) shows

| (2.6) |

Typical values of z0 range from several angstroms to several nanometres for van der Waals interaction, and can be even larger for electrostatic and other long-range interactions. Substituting equation (2.6) back into equation (2.5), the interaction stress can be rewritten as

| (2.7) |

Recall that the work of adhesion wad is defined as the work required to separate two surfaces from the equilibrium separation to infinity. Equation (2.7) implies that

| (2.8) |

Since the separation of the interface is accompanied by the creation of two new surfaces, wad is normally understood as the differential surface energy Δγ=γ1+γ2−γ12, where γ1 and γ2 are the surface energies of two solids and γ12 is the interfacial energy. Then equation (2.8) provides a relationship between the constant B and the work of adhesion (wad) and the equilibrium separation (z0). Inserting equation (2.8) into equation (2.7) yields

| (2.9) |

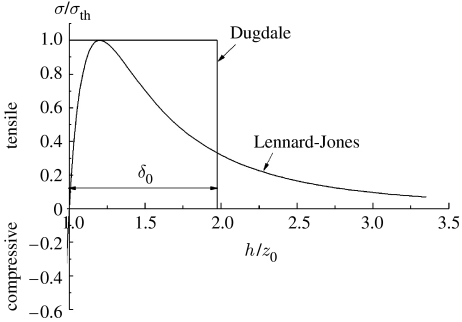

This is the commonly used inter-surface force expression of the interaction stress between two solids as a function of their surface separation. Figure 2 plots this interaction stress as a function of separation, together with Dugdale's (1960) simplified interaction law. Given wad and z0, the maximum interaction stress or the theoretical adhesion strength occurs at h=31/6z0. Although equation (2.9) is derived on the basis of two solids with planar parallel surfaces, it is often applied to unparallel or curved surfaces (Greenwood 1997) as long as the contact region is much smaller than the solid surfaces. Based on the above inter-surface force model, it can be shown that the actual adhesion strength between two solids tends to increase as the size of the contacting objects is reduced and eventually saturates at the theoretical adhesion strength below a critical size (Persson 2003; Gao & Yao 2004; Gao et al. 2005; Tang et al. 2005). However, at very small length scales, intermolecular interaction can occur over a large fraction of the surfaces of contacting objects. In that case, it becomes questionable whether the inter-surface force model can still describe intermolecular interactions between two solids. In §§3–5, we shall adopt the more fundamental intermolecular force model, instead of the inter-surface force model, to investigate the size dependence of adhesion strength at small scales. For simplicity, deformation of solids is neglected in this paper.

Figure 1.

Schematic of interactions (a) between a single molecule and a solid half-space and (b) between two solid half-spaces (adapted from Israelachvili 1992).

Figure 2.

LJ and Dugdale interaction laws between two parallel solid spaces.

3. Size dependence of adhesion strength between a sphere and a solid half-space

Let us first consider the interaction between a sphere and a solid half-space. Equation (2.2) shows that the interaction energy between a single molecule and a solid half-space is

where ρ1 is the molecular density of the solid and D is the separation between the molecule and the solid surface. Taking advantage of this expression, the interaction potential between a sphere and a solid half-space, as shown in figure 3a, can be obtained from the following integration:

| (3.1) |

where D stands for the shortest distance between the sphere and the solid surface; and R and ρ2 are the radius and molecular density of the sphere, respectively. Differentiating equation (3.1) with respect to D leads to the adhesion force,

| (3.2) |

Using equations (2.6) and (2.8), equation (3.2) can be rewritten as

| (3.3) |

where

is a dimensionless function with

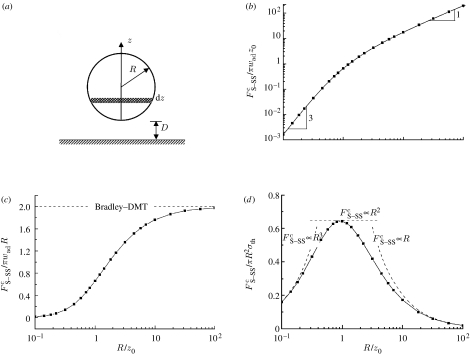

Once wad, z0 and R are given, equation (3.3) expresses the adhesion force as a function of separation. The maximum adhesion force, or the so-called pull-off force , can be readily determined. Figure 3b plots the calculated pull-off force as a function of the radius R of the sphere. One can see that for small spheres, is proportional to R3, suggesting that the pull-off force is dominated by the volume of the sphere. As the sphere grows, such cubic dependence evolves asymptotically into a linear dependence, signifying a transition between the bulk-dominated regime at very small sizes to the surface-dominated regime at large sizes. Figure 3c shows the evolution of with R/z0. As R→∞, it is seen that the pull-off force asymptotically approaches the prediction from classical Bradley and Derjaguin–Muller–Toporov (DMT) models (Bradley 1932; Derjaguin et al. 1975).

Figure 3.

(a) Schematic of a sphere (S) in adhesive contact with a solid half-space (SS). Scale dependence of the pull-off force normalized by (b) πwadz0 and (c) πwadR. (d) Scale dependence of the normalized adhesion strength.

Figure 3d shows the normalized adhesion strength as a function of the radius of the sphere. For R≫z0, the adhesion strength rises as R decreases and reaches a peak value of 0.65σth at R≈z0. Other than the coefficient 0.65, this peak value agrees with the prediction of the inter-surface force model. However, as R decreases further, instead of saturating at a limiting value as would be predicted by the inter-surface force model, the adhesion strength actually drops down to zero. Such a behaviour is due to the R3 dependence of the pull-off force at small size scale and cannot be captured by inter-surface force models. The behaviour shown in figure 3b that the pull-off force changes from a linear (R) to a cubic (R3) dependence as R decreases holds also for the contact between the two elastic solids. While the R3 dependence of the pull-off force can only be captured by the full intermolecular force model, the R dependence at large R has been captured by all classical contact models such as Johnson–Kendall–Roberts (Johnson et al. 1971), DMT (Derjaguin et al. 1975) and M–D models (Maugis 1992).

4. Size dependence of adhesion strength between two spheres

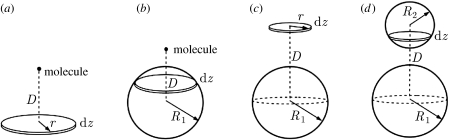

The analysis of §3 can be generalized to interactions between two spheres. Let us begin with calculating the interaction potential between a single molecule and a thin circular disc (figure 4a). The resulting molecule–disc potential will be used as a basis to construct the potential between a single molecule and a sphere (figure 4b) and subsequently the potential between two spheres (figure 4d). The detailed derivation is summarized below.

Figure 4.

A bottom-up integration scheme for calculating the interaction potential between two spheres. One begins with calculating the potential between (a) a single molecule and a circular thin disc. The obtained result is used to construct the potential between (b) a single molecule and the bottom sphere. Similar integration scheme is applied to the upper sphere so as to obtain the potentials between (c) a sphere and a circular thin disc and (d) two spheres.

Consider a single molecule and a circular disc with infinitesimal thickness dz (figure 4a). If the molecule is on the axis of revolution of the disc, the interaction potential can be integrated from the LJ potential in equation (2.1) as

| (4.1) |

where r and ρ1 stand for the radius and molecular density of the disc, respectively, and D is the separation between the molecule and the centre of the disc. Substituting equation (2.6) into (4.1) gives

| (4.2) |

Based on equation (4.2), the interaction potential between a single molecule and a sphere (figure 4b) can be calculated as

| (4.3) |

where

and

where D is the distance between the molecule and the centre of the sphere; and R1 is the radius of the sphere. Equation (4.3) is now used to construct the interaction potential between a circular disc of infinitesimal thickness dz and a sphere (figure 4c) as

| (4.4) |

where

r and ρ2 are the radius and molecular density of the disc, respectively, and D is the distance between the disc and the centre of the sphere. Recalling equation (2.8),

equation (4.4) becomes

| (4.5) |

Finally, the interaction potential between two spheres is constructed from equation (4.5) as

| (4.6) |

where and , R2 and D being the radius of the second sphere and the separation between the centres of the two spheres, respectively. Without loss of generality, we assume R1≥R2. According to equation (4.6), the interaction force between the two spheres is

| (4.7) |

Letting

equation (4.7) can be rewritten as

| (4.8) |

Once , , wad and z0 are given, equation (4.8) gives FS–S as a function of the normalized centre–centre distance between the spheres. Numerical quadrature can be used to calculate FS–S and the pull-off force .

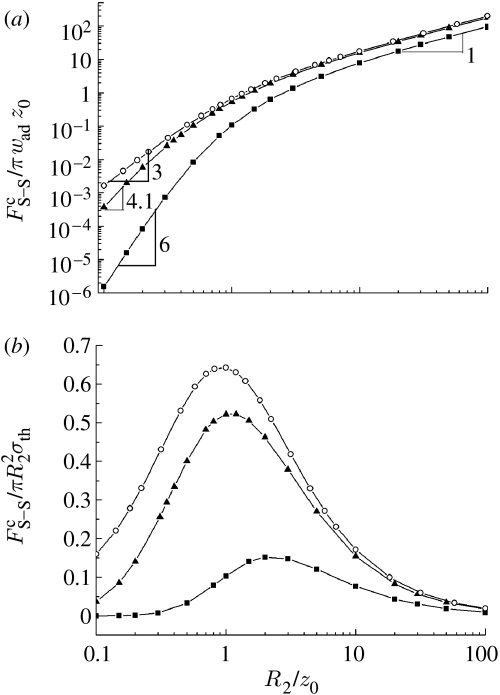

Taking R1/R2=1.0 and 10, the pull-off force is calculated as a function of R2 and plotted in figure 5a. For comparison, the pull-off force between a sphere and a solid half-space is also plotted as in the limiting case of R1/R2→∞. As expected, the pull-off force between two spheres exhibits a linear dependence on R2 at large sizes irrespective of the ratio R1/R2. This behaviour is consistent with Bradley's (1932) model in which the pull-off force between two rigid spheres is proportional to the composed radius (R1+R2)/R1R2 and therefore to R2 when the ratio R1/R2 is given. On the other hand, in the small-size limit, the scale dependence of the pull-off force depends on R1/R2. For instance, when R1/R2=1, the pull-off force scales with . This is because at small scales the pull-off force is proportional to the product of the volumes of the two spheres and therefore to when R1=R2. For R1/R2 ranging from 1.0 to ∞, the pull-off force at the small-size scale is found to be proportional to , where 3<m<6. For example, when R1/R2=10.0, our numerical results show that m≈4.1. Figure 5b displays the size dependence of the adhesion strength defined as the pull-off force normalized by the projected area of the smaller sphere . Similar to the case discussed in §3, the adhesion strength between two spheres exhibits a peak value at R2≈z0, while it approaches zero in the extreme cases of R2→0 and R2→∞. The absence of strength saturation at small length scales is at odds with the prediction of inter-surface force models (Persson 2003; Gao et al. 2005; Tang et al. 2005). Nevertheless, figure 5b shows that the maximum adhesion strength would never exceed 0.65σth, irrespective of the value of R1/R2, suggesting that σth can still serve as a reasonable estimate for the upper bound of adhesion strength between two spheres, as we did in previous work (Yao et al. 2007).

Figure 5.

Size dependence of (a) the normalized pull-off force and (b) the normalized adhesion strength between two spheres. Circles, R1/R2=infinity; triangles, R1/R2=10.0; squares, R1/R2=1.0.

5. Interaction between a hemisphere-ended cylinder and a solid half-space

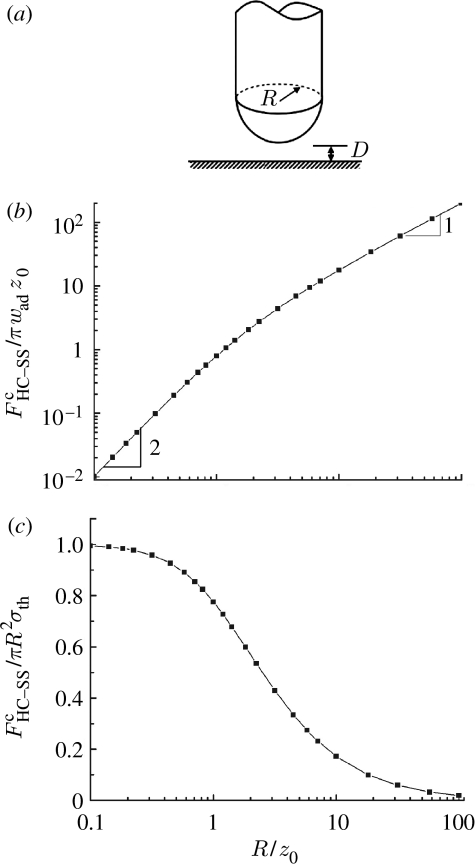

Based on the intermolecular force model, we have illustrated that the adhesion strength between a sphere and a solid half-space or that between the two spheres eventually drops to zero as the characteristic size of the system decreases. However, we wish to point out that this does not mean that the application of intermolecular force model necessarily leads to the conclusion that there is no saturation of adhesion strength at small length scales. To demonstrate this point, consider a hemisphere-ended cylinder in adhesive contact with a solid half-space (figure 6a). In this case, the interaction potential is given by

| (5.1) |

where D is the distance between the apex of the hemisphere-ended cylinder and the solid half-space. Substituting equations (2.6) and (2.8) into equation (5.1) gives

where and . Therefore, the adhesion force between a hemisphere-ended cylinder and a solid half-space is

| (5.2) |

The pull-off force , corresponding to the maximum of FHC–SS, can be readily obtained. Figure 6b shows the size dependence of the pull-off force. Not surprisingly, scales up linearly with the radius R of the cylinder at large sizes. However, in the small-size limit R→0, it exhibits an R2 dependence. This is because at small length scales, the pull-off force is proportional to the effective interaction volume, that is, the volume of material which participates in the interaction. For a cylinder, the dimension in the longitudinal direction is much larger than the range of interaction forces. Hence, the effective interaction volume is proportional to the cross-sectional area multiplied by the thickness of the interaction range, which is normally independent of R, resulting in the R2 dependence of the pull-off force. Such size dependence of the pull-off force eventually leads to the saturation of adhesion strength in the limit of small size, as shown in figure 6c.

Figure 6.

(a) Schematic of a hemisphere-ended cylinder (HC) in adhesive contact with a solid half-space (SS). Size dependence of (b) the normalized pull-off force and (c) the normalized adhesion strength between a hemisphere-ended cylinder and a solid half-space.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we have shown that the conventional inter-surface force models fail to describe correctly the interaction force between two spheres at the small-size limit. This is demonstrated by directly integrating the intermolecular forces between two spheres to examine the size dependence of adhesion strength at small scales. Our analysis is thus more rigorous than the inter-surface force models in adhesive contact mechanics. Our results showed that the adhesion strength between two spheres or between a sphere and a solid half-space exhibits a peak value at an optimal size, and eventually drops to zero as the size decreases further. We also showed that the adhesion strength between a hemisphere-ended cylinder and a solid half-space would saturate at the theoretical adhesion strength below a critical size in agreement with predictions from inter-surface force models. Therefore, it cannot be generally concluded that the adhesion strength would (or would not) saturate at small contact size. Whether such saturation actually occurs depends on the limit of the interaction volume at small sizes. If the interaction volume scales with the characteristic size R of the system as R3, as in the case of nanoparticles, there will be no strength saturation but a maximum strength at an optimal size. If the interaction volume scales as R2, as in the case of hairs/fibres, the adhesion strength will eventually saturate at the theoretical adhesion strength. Although this study has been based on the assumption of rigid solids, we expect that the conclusion should hold at least qualitatively for contact between elastic solids.

References

- Arzt E, Gorb S, Spolenak R. From micro to nano contacts in biological attachment devices. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:10 603–10 606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1534701100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autumn K, Liang Y.A, Hsieh S.T, Zesch W, Chan W.P, Kenny T.W, Fearing R, Full R.J. Adhesive force of a single gecko foot-hair. Nature. 2000;405:681–685. doi: 10.1038/35015073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autumn K, et al. Evidence for van der Waals adhesion in gecko setae. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:12 252–12 256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192252799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley R.S. The cohesive force between solid surface and the surface energy of solids. Phil. Mag. 1932;13:853–862. [Google Scholar]

- de Boer J.H. The influence of van der waals forces and primary bonds on binding energy, strength and orientation, with special reference to some artificial resins. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1936;32:10–36. doi: 10.1039/tf9363200010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Derjaguin B.V, Muller V.M, Toporov Y.P. Effect of contact deformations on the adhesion of particle. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1975;53:314–326. doi: 10.1016/0021-9797(75)90018-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dugdale D.S. Yielding of steel sheets containing slits. J. Mech. Phys. Solids. 1960;8:100–108. doi: 10.1016/0022-5096(60)90013-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H, Chen S. Flaw tolerance in a thin strip under tension. J. Appl. Mech. 2005;72:732–737. doi: 10.1115/1.1988348. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H, Yao H. Shape insensitive optimal adhesion of nanoscale fibrillar structures. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:7851–7856. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400757101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H, Ji B, Jaeger I.L, Arzt E, Fratzl P. Materials become insensitive to flaws at nanoscale: lessons from nature. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:5597–5600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0631609100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H, Wang X, Yao H, Gorb S, Arzt E. Mechanics of hierarchical adhesion structures of geckos. Mech. Mater. 2005;37:275–285. doi: 10.1016/j.mechmat.2004.03.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood J.A. Adhesion of elastic spheres. Proc. R. Soc. A. 1997;453:1277–1297. doi: 10.1098/rspa.1997.0070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamaker H.C. The London–van der Waals attraction between spherical particles. Physica. 1937;4:1058–1072. doi: 10.1016/S0031-8914(37)80203-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Israelachvili J.N. 2nd edn. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1992. Intermolecular and surface forces. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K.L, Kendall K, Roberts A.D. Surface energy and contact of elastic solids. Proc. R. Soc. A. 1971;324:301–313. doi: 10.1098/rspa.1971.0141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maugis D. Adhesion of spheres: the JKR–DMT transition using a Dugdale model. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1992;150:243–269. doi: 10.1016/0021-9797(92)90285-T. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Persson B.N.J. Nanoadhesion. Wear. 2003;254:832–834. doi: 10.1016/S0043-1648(03)00233-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang T, Hui C.Y, Glassmaker N.J. Can a fibrillar interface be stronger and tougher than a non-fibrillar one? J. R. Soc. Interface. 2005;2:505–516. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2005.0070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao H, Gao H. Mechanics of robust and releasable adhesion in biology: bottom-up designed hierarchical structures of gecko. J. Mech. Phys. Solids. 2006;54:1120–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.jmps.2006.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yao H, Gao H. Mechanical principles of robust and releasable adhesion of gecko. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2007;21:1185–1212. doi: 10.1163/156856107782328326. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yao H, Ciavarella M, Gao H. Adhesion maps of spheres corrected for strength limit. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2007;315:786–790. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2007.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]