Abstract

Self-healing via a vascular network is an active research topic, with several recent publications reporting the application and optimization of these systems. This work represents the first consideration of the probable failure modes of a self-healing system as a driver for network design. The critical failure modes of a proposed self-healing system based on a vascular network were identified via a failure modes, effects and criticality analysis and compared to those of the human circulatory system. A range of engineering and biomimetic design concepts to address these critical failure modes is suggested with minimum system mass the overall design driver for high-performance systems. Plant vasculature has been mimicked to propose a segregated network to address the risk of fluid leakage. This approach could allow a network to be segregated into six separate paths with a system mass penalty of only approximately 25%. Fluid flow interconnections that mimic the anastomoses of animal vasculatures can be used within a segregated network to balance the risk of failure by leakage and blockage. These biomimetic approaches define a design space that considers the existing published literature in the context of system reliability.

Keywords: self-repair, branched network, polymer composite, human circulation

1. Introduction

Since the birth of modern engineering during the industrial revolution, increasingly challenging endeavours have always driven advanced scientific understanding and innovative design solutions in all fields of engineering. Two notable engineering advances of the last two centuries have been the unprecedented safety and reliability of modern high-performance systems such as aircraft and the dramatic improvement in the performance of materials. Both of these qualities are also found in natural systems.

Performance of structural materials has been at the forefront of advancement in high-performance systems and modern fibre-reinforced polymer composite materials are revolutionizing structural design in aerospace, marine and terrestrial transportation. A limiting factor is the performance of such composite materials under impact loading. Composite materials do not plastically deform like a metal structure, so impact damage can create cracks and damage internally. This can be difficult to detect visually (Richardson & Wisheart 1996; Abrate 1998; Tomblin et al. 1999). Thus, a fibre-reinforced polymer composite material could directly benefit from incorporating an ability to self-heal, because structures are designed conservatively to allow for service damage. Trask et al. (2007a) have reviewed the key approaches to engineering self-healing used to date and have offered a perspective on where biological systems could be used as simple inspiration or be more systematically mimicked to provide the next generation of self-healing systems. Readers are referred to the works of Zako & Takano (1999), Chen et al. (2002) and Hayes et al. (2007) as examples of solid-state healing approaches not considered herein. To date, successful liquid-based self-healing systems have been based on the release of limited quantities of stored healing agent from polymer microcapsules (e.g. Kessler & White 2001; White et al. 2001; Kessler et al. 2003; Brown et al. 2004, 2005; Rule et al. 2005; Cho et al. 2006; Jones et al. 2007; Kamphaus et al. 2008) or hollow glass fibres (e.g. Bleay et al. 2001; Pang & Bond 2005a,b; Trask & Bond 2006; Trask et al. 2007b; Williams et al. 2007a). It is desirable that a self-healing system is autonomous: the impact damage itself initiates the healing process. A biomimetic vascular network that allows a healing agent to be distributed from a reservoir throughout a structure so that damage can be completely infiltrated with healing agent under modest pressure was identified as an advance for liquid-based healing approaches (Trask et al. 2007a). Two successful pilot studies have recently been reported: an interconnected network of microchannels in a pure polymer (Toohey et al. 2007) and vessels embedded in the core of a sandwich structure (Williams et al. 2007c). Geometric optimization of the vascular networks used for self-healing has been previously reported in the form of a statically pressurized grid network (Bejan et al. 2006; Wang et al. 2006) and a branching network (Kim et al. 2006). Wechsatol et al. (2005) have investigated the use of interconnecting paths between the branches of a tree network to provide multiple supply routes in case of damage. A wider review of the constructal theory used in these studies is provided by Bejan & Lorente (2006). Emerson et al. (2006) have considered the optimization of branched networks for miniaturized fluid handling in ‘lab on a chip’ applications. Williams et al. (2007b) have developed a design scheme to tailor the vessel branching in a self-healing sandwich panel to address damage of a critical size and have derived a biomimetic expression for the optimum vessel diameter for a minimum mass vascular system (Williams et al. 2008). The latter used a modification of Murray's law (Murray 1926), which was originally derived to give the optimum vessel diameter and branching relationships in the human circulatory system.

There is considerable research momentum behind optimizing vascular networks for self-healing and other applications, but the question of reliability has not yet been addressed at the system level. The reliability of the self-healing system itself is under consideration, i.e. what could cause the self-healing system to be unable to achieve self-healing after a damage event. It is difficult to estimate the probable reliability of self-healing systems, because all current work is at an early stage of research. Achieving high reliability is essential if self-healing is to be considered for applications in future high-performance systems. Self-healing is a new direction for materials engineering. It is unclear whether traditional approaches for reliability in engineering systems are best suited to this nascent technology and the aim of this work is to consider this question. Both animals and plants feature fluid flow networks integrated into load-bearing materials, and therefore serve as a useful source of inspiration for probable failure modes and reliability strategies since it can be assumed that these have evolved to ensure system success. Installing a self-healing system into an engineering material or structure may incur penalties in terms of mass, disruption to structural performance, manufacturing complexity, direct costs and indirect costs (e.g. certification, periodic maintenance). The primary design driver will vary considerably in individual applications. Many high-performance engineering systems are vehicles in which mass has a direct and significant effect on fuel consumption. An ideal, mature, self-healing structure would incur a negligible penalty on structural performance and the additional mass of the self-healing system could be traded against a less conservatively designed structure, so there is a clear driver for minimizing the mass of the self-healing system itself. The approach adopted in this work was to analyse the probable failure modes of an engineering self-healing system and then compare these to the human circulatory system. Critical failures in both systems are then compared and conceptual biomimetic design approaches to mitigate the failure modes identified as the most critical are developed. A model to estimate the minimum mass of a vascular network was previously reported (Williams et al. 2008) and this can be used as a basis to critically analyse these conceptual designs.

2. Failure modes, effects and criticality analysis

2.1 Justification and assumptions

A structured, engineering approach to investigate failures that could impact on the operation of a system is to perform a failure modes, effects and criticality analysis (FMECA). A FMECA was therefore carried out on a generic self-healing vascular network according to BS5760 (British Standards Institute 1991). The purpose of a self-healing vascular network is to distribute a fluid healing agent through a structure such that damage to the structure will cause the rupture of purposefully placed vessels. This should allow the liquid healing agent to bleed out, cure and restore some or all of the properties of the structure. For the purpose of this analysis the failure of the system is, therefore, defined as the failure to achieve self-healing. Some assumptions must be made in order to generate a generic vascular network for analysis. These are based on the currently envisaged form of the self-healing vascular network. The following is assumed.

The pressure for fluid flow is supplied by a pump or reservoir having the capacity for multiple healing events and may take any form, e.g. pressurized cylinder or separate reservoir and pump.

A main supply vessel leads from the pump and branches into intermediate supply vessels, neither of these vessel types are designed to rupture under an impact event, their purpose is fluid supply.

The smallest vessels are intended to be ruptured by impact damage to release healing agent into the damage.

The healing agent will require rupture of a vessel to initiate bleeding into any damage, and a stimulus external to the network to initiate the cure reaction; this may be intimate contact with a liquid hardener phase released from another network, catalyst or other physical stimulus.

If the network is circulating (closed-loop), it is assumed that the intermediate and main supply vessels are duplicated symmetrically to form the return path and, to first order, will share the failure modes and criticality as the supply path.

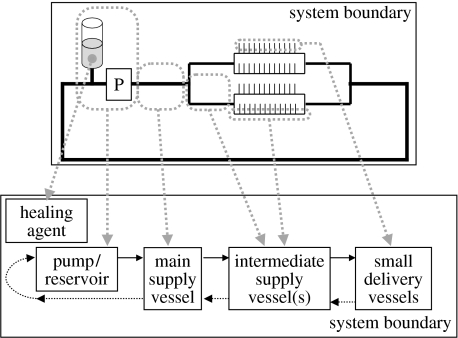

A generic self-healing vascular system is shown schematically in figure 1. A system boundary is indicated, which simplifies the analysis by excluding external factors such as catastrophic failure of the vehicle on which the system is deployed or the effect of a failed self-healing system on the structure it protects.

Figure 1.

Schematic of a generic vascular network self-healing system. Block diagram showing the component breakdown.

In order to perform an analysis, it is necessary first to define the probability of a failure mode occurring. In practical design studies the probability of each component failure mode is known, at least approximately, and this can be used directly. Self-healing vascular networks are a new research topic, so it is not possible to obtain accurate failure probabilities from service experience. Fortunately, the purpose of this analysis is not to quantify the reliability of the system, but to identify the critical failure modes at which efforts to improve reliability should be directed. It is therefore sufficient to use a simple three-point relative scale to define the probability of failure. The probability of each failure mode is estimated by the authors' experience with first-generation self-healing systems and when the components are used in other applications. The severity of a failure for the system as a whole can also be estimated on a simple three-point scale. The product of the probability and severity of each failure mode gives the criticality of each failure mode (British Standards Institute 1991). These are expressed, along with the criteria for the probability and severity levels, as a criticality matrix in table 1.

Table 1.

Probability, severity and criticality matrix.

| severity | negligible effect on system operation | degraded system operation | total system failure | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| probability | levels | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| likely to occur several times during life of system | 3 | 3 | 6 | 9 |

| unlikely to occur, may occur once or twice during the life of system | 2 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| unlikely to occur during the life of the system | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

The lack of operational experience with self-healing systems means much of the FMECA is conducted using engineering judgement. The engineering vascular system has many parallels with the human circulatory system. Examining common failure modes and criticality has value in gaining understanding and confidence in the analysis. A FMECA was therefore carried out on the human circulatory system by the authors possessing a medical background, using only the same component breakdown. There does not appear to be any published examples of this method being applied to biological systems themselves, although there are some examples of it being applied to artificial hearts (Patel et al. 2005; Zapanta et al. 2005), the management system of blood transfusions (Marey et al. 1997) and medical processes (Coles et al. 2005).

2.2 FMECA results

The FMECA results for a vascular self-healing system and the corresponding analysis for the human system are presented in full in the electronic supplementary material. Some additional failure modes for the engineering system were identified from the failure modes of the biological system, but none of these failure modes were identified as being critical. These additional failure modes are also presented in full in the electronic supplementary material. All the failure modes identified in the analysis could be considered critical if they occurred while a system was in operation. It is also helpful to identify any additional failure modes that could present a significant maintenance challenge, i.e. a failure that could be especially costly to repair. Possible repairs for each failure mode were suggested and scored on a three-point scale. The complete tabulation is included in the electronic supplementary material. The only failure mode that scored both the maintenance criticality greater than nine and had not already been identified as a critical failure from the initial analysis was penetrating structural damage that breached an intermediate supply vessel. This failure was added to the list of critical failure modes for the engineering system.

Despite the difference in the primary role of a vascular self-healing system and the human circulation, and the fact that the analysis was carried out by authors with different scientific backgrounds, many similar failure modes were identified. One key difference in approach is that those with an understanding of medicine tended to link symptoms back to an underlying cause rather than think of a component failure forward to an effect and criticality. There appears to be little literature discussing the use of engineering techniques such as FMECA in life sciences applications; greater use could offer interesting perspectives. A key element of this study was also to separate the severity of a failure from effects on the host vehicle, i.e. consistent application of the system boundary. This is an essential generalization given the maturity of self-healing technology and the lack of service experience with real structures but is difficult to consider dispassionately in a human patient. In any practical engineering application, the interaction between the self-healing system and structure it protects will need to be considered for detailed system design.

For each component the critical failure modes are compared in table 2. The failure modes of the engineering system have been classified into six fundamental groups (I–VI). Approaches for improved reliability should be developed for:

pump/reservoir underperformance or complete failure,

fluid leakage,

vessel blockage or constriction by cured resin or debris,

failure of bleeding mechanism by damage failing to rupture a riser,

healing resin cured properties degraded by unfavourable cure conditions, and

healing resin performance degraded by time or temperature.

Table 2.

Comparison of critical failure modes.

| component | system | failure mode | criticality | fundamental failure groupa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pump/reservoir | engineering system | pump underperforms | 4 | I |

| pump mechanical failure | 6 | I | ||

| fluid leak: minor (e.g. leaky seal) | 4 | II | ||

| human circulatory system (heart) | muscle failure | 4 | I | |

| reduction in power supply (coronary) | 3–6 | n.c. | ||

| disruption to nerve control (arrhythmia) | 3–9 | n.c. | ||

| main and intermediate supply vessels | engineering system | blockage of main vessel leak of intermediate vessel due to penetrating structural damage | 6 3b | III II |

| human circulatory system (aorta, arteries and arterioles) | embolus (e.g. stroke, the bends)constrictionage: loss of elasticity | 466 | IIIIIIn.c. | |

| small delivery vessels | engineering system | blockagefailure to bleed following low velocity damage of specified level | 64 | IIIV |

| human circulatory system (capillaries) | external temperaturevasodilatation | 63–6 | n.a.n.a. | |

| healing agent | engineering system | failure to cure: no intimate contact between resin and initiator (whether hardener, catalyst or physical stimulus) | 4 | IV |

| service degradation: reduced cure potential | 6 | VI | ||

| failure to achieve optimum cured properties | 6 | V | ||

| premature cure in network: localized, stationary clotpremature cure in network: mobile clot | 466 | IIIIIIIII | ||

| properties affected by temperature significantly exceeding design value | 4 | VI | ||

| human circulatory system (blood) | thrombosis: localized clot forms due to local damage or hypercoagulable state | 4–6 | III | |

| significant variation in blood volume | 6 | II |

Fundamental failure mode groups: I, pump/reservoir failure; II, fluid leakage; III, vessel blockage; IV, damage fails to rupture riser; V, healing resin fails to fully cure; VI, degraded healing agent; n.c., not critical; n.a., not applicable.

This failure mode has been included because it was identified as being maintenance critical due to the likelihood of complex repair. See discussion in §2.2 and electronic supplementary material.

Critical failure modes in the human system are either linked to a fundamental failure mode or are classified as being not applicable (n.a.) or non-critical (n.c.) for the engineering system. Table 2 shows that many of the critical failure modes for the two systems are distinct. This highlights the difference in reliability approach that could be used to enhance the engineering system.

3. Reliability strategies

Having identified the fundamental groups of failure mode it is desirable to identify reliability strategies that could address each group, and the potential mass penalties of these approaches.

3.1 Component and system redundancy

In aerospace and other safety critical applications, it is usual to provide duplicate or triplicate components and systems to provide security against all possible failure modes of the individual system. Independent parallel components confer the enormous advantage of ease of certification for engineering systems. The probability of all independent, parallel components failing, p, is given by

| (3.1) |

where n is the number of independent systems and pcomponent is the probability of individual component failure. In practice, this means that if starting with reliable individual systems, the chance of a total loss of functionality can be reduced to practically zero by duplicate (n=2) or triplicate (n=3) systems. An example of this approach would be the installation of duplicate parallel pump/reservoirs to feed a flow network. This would address failure modes in group I: pump underperformance or failure. Milsum & Roberge (1973) have shown that pumping power represents one-third of the total system power of a Murray's law optimized channel, with maintenance power representing the other two-thirds. Williams et al. (2008) have shown that Murray's optimization also applies to a minimum mass system. The total mass of a system with duplicated redundant pumps would, therefore, be increased by one-third. A system with triplicate redundant pumps would be two-thirds more massive. However, if each redundant pump is sized to provide full system power the combined power-to-weight ratio of the pumps is substantially reduced. A new optimum vessel diameter can, therefore, be selected to minimize the mass penalty. Williams et al. (2008) have previously derived the mass of a section of network as the sum of a pump term and a tube term

| (3.2) |

where Q is the volumetric flow rate; l is the section length; μ is the fluid viscosity; di is the internal diameter of the section of vessel; and k is the power-to-mass ratio of the pump. The first term therefore represents the mass incurred to impart the required power to the flow. The second term gives the mass of tubing and fluid, hence ρtube is the density of the tubing material; c is a constant of proportionality linking vessel wall thickness with internal diameter; and ρfluid is the density of the circulating fluid. Constants A and B are introduced to simplify the expression. With the addition of the number of pumps, npump, into the first mass term the expression becomes

| (3.3) |

Differentiation with respect to internal diameter gives the optimum internal diameter,

| (3.4) |

The optimum internal diameter, therefore, increases with the sixth root of the number of independent pumps. If equation (3.4) is substituted into equation (3.3) and simplified, the influence of the number of pumps on overall mass can be inspected,

| (3.5) |

Thus, the overall mass scales with the cube root of the number of pumps. Table 3 summarizes this and shows the value in considering the number of pumps when selecting the vessel diameter.

Table 3.

Mass penalty incurred by pump redundancy.

| number of pumps (redundancy) | relative mass | relative mass with re-optimized tube diameter |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| 2 (duplex) | 1.333 | 1.260 |

| 3 (triplex) | 1.667 | 1.442 |

| 4 (quadruplex) | 2.000 | 1.587 |

The human circulatory system provides a dense network of capillaries, tailored to the demands of the local tissue (Gray 1918) and permitting localized redundancy whereby the temporary blockage of capillaries is a normal feature of operation. This is reflected in the lack of crossover between critical failure modes for this component in table 2. Initial theoretical studies on network design for self-healing materials (Williams et al. 2007b) have used a minimum number of small delivery vessels to address typical impact damage in sandwich structures by spacing the vessels to correspond with the damage size. An increase in the density of small delivery vessels so they become redundant would address riser failure modes in groups III (blockage) and IV (failure to bleed), but increases the total network mass. The absolute and relative mass penalty of introducing redundant risers increases with riser size and the network density; both are highly application specific. A numerical study based on the network design for a simple beam presented by Williams et al. (2007b) was undertaken to estimate the mass penalty, assuming that the small delivery vessels are the same size as the smallest supply vessels. A simple sensitivity analysis using a range of probable input values gives a relative mass of a system with duplex riser redundancy between 1.23 and 1.42. The same sensitivity analysis gives a relative mass between 1.45 and 1.83 for a system with triplex riser redundancy. Clearly, these estimates are application specific but do give an indication of the probable magnitude of the penalty, suggesting it is roughly comparable to providing redundant pumps. Unlike the effect of adding pumps, there is no general solution for the penalty of small vessel redundancy owing to the possible variation in network configuration. As the riser spacing can be adjusted throughout the structure to allow for variation in critical damage size, the degree of redundancy can vary through a structure depending on the probability of impact damage in a particular location. This design flexibility could reduce the mass penalty. On the other hand, the influence of the density of these vessels on the structural performance of a self-healing material could be detrimental. By definition, the small delivery vessels need to penetrate through the thickness of a material to areas that could experience damage, such as the skin–core bond region of a sandwich panel. There is a clear driver for increasing the density of the small delivery vessels in critically loaded regions of a structure. Any weakness caused by the presence of the risers is compounded by their form and location. This could be more significant than the actual weight penalty of the vessels and is an area in which studies are ongoing.

It is common in critical aerospace systems to duplicate whole systems rather than just individual components. The argument for this approach is the same as that given for equation (3.1), with two or three reliable, independent systems the chance of all failing can be reduced to virtually zero. This is an approach that is well established and accepted by certification authorities. For a rigorous application, two (or more) small delivery vessels must supply each region of the critical damage size from two or more completely redundant systems (i.e. separate pump, main and intermediate vessels). It is easy to see that such an approach is not easy to apply in a point-to-area network where many points must receive multiple supplies from multiple reservoirs. Duplex redundancy, therefore, doubles the overall system mass, triplex redundancy triples it and so on. This is costly to start with, but as discussed previously, any possible detrimental effect of riser density on the structural performance must also be considered. The overall mass penalty for a system protecting a complex structure can be mitigated somewhat with different levels of redundancy in different regions of a structure. There is an engineering precedent for this: it is customary for primary flight controls of aircraft, those immediately essential for flight, to be supplied by at least three independent systems, while secondary systems are commonly powered by only one or two systems. This is an example of a point-to-point network, with a relatively small number of individual components requiring supply. The high cost of whole system redundancy for point-to-area distribution perhaps explains why natural systems have rarely evolved this approach; even in cases of duplicated organs it is questionable whether this is for redundancy purposes. The circulatory system is critical to the operation of human beings and yet there has clearly been no evolutionary advantage to having two independent circulatory systems powered by two hearts.

3.2 Monitoring

Feedback is an essential feature in the reliability of biological systems; a drop in blood volume initiates events that attempt to correct the deficiency. The detection and rectification of failures in engineering systems are usually initiated by some form of sensor. Human intervention can then ‘close the loop’ and restore the system to service by maintenance action such as refilling the fluid reservoir. A failure detection system may, therefore, be desirable in a self-healing vascular system. Two simple conditions that would be of immediate value in detecting failures in groups I (pump failure) and II (leakage) would be low system pressure and low reservoir volume, respectively. More complex monitoring could apply to the condition of the healing resin to address group VI (healing agent degradation). With modern electronics and sensors, it is reasonable to assume that the mass of these are negligible relative to the rest of the network in all but the smallest of systems. It is important to note that an integrated sensing system of this kind would not stop the self-healing itself from being autonomous.

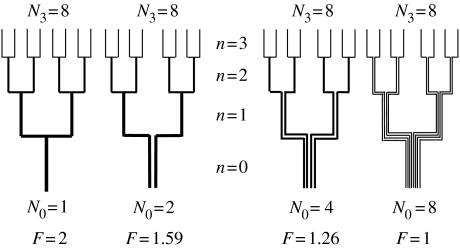

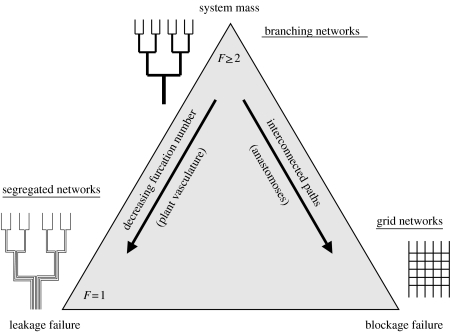

3.3 Flow segregation

Leakage (failures in group II) could result in the total failure of a self-healing system if the leakage rate is sufficiently rapid that monitoring does not give sufficient warning of impending failure. In the human vascular system, this failure mode is less critical because vasoconstriction and blood clotting restrict fluid loss as well as initiate structural wound repair. In an engineering self-healing system, no currently available resin system can be assured to achieve both structural and vessel repair. In engineering systems, this failure mode is typically addressed by redundant systems. Vascular networks in plants offer an alternative evolutionary approach: a segregated network. Fluid is drawn through plant xylem tubes under negative pressure, and a single breach will cause the network to fill with air and the flow to cease (McCulloh et al. 2003, 2004). The segregation concept effectively blurs the distinction between generations with vascular conduits running adjacent and parallel. This allows the different conduits to break away from each other at a junction, forming what is effectively a new generation, without a true junction in the fluid flow path. The conduit furcation number, F, is the ratio of the number of daughter-to-parent conduits at each generation. At a single furcation this must take an integer value. However, over several generations with different individual furcation values, this effectively allows a non-integer value of F for the overall system. This is illustrated in figure 2 with schematics of several generations of various vasculatures.

Figure 2.

Branching in fourth-generation (n=3) animal (F=2) and plant (F<2) networks.

At a junction in a branching network, a parent vessel can divide into an integer number of daughter vessels. If this degree of branching is termed the furcation number, F, in the nth generation the number of vessels N given from a single starting vessel is

| (3.6) |

In a general branching network there may be more than one starting vessel. Thus, in general, the number of vessels in the nth generation, Nn, is given by

| (3.7) |

where N0 is the number of vessels in the first generation. As discussed above, a non-integer value for the furcation number, F, is possible and can be determined by rearrangement of equation (3.7),

| (3.8) |

This relationship shows how the furcation number of the networks in figure 2 can be determined: it is the geometric mean furcation of the three junctions, and because N0 cannot exceed Nn and both are integers, a finite number of solutions are available for a given network. McCulloh et al. (2003) have measured values of F less than 1.45 for plant structures. Values of furcation number closer to 2 will give better hydraulic efficiency but are more vulnerable to damage in that more of the network will be lost from a single point of leakage. Notably, they report that the highest values of F occurred in the leaves of the plants studied: leaves being disposable organs show a lesser drive for reliability. In a broader sense, this segregated vascular supply is a feature of the compartmentalization response to damage in plants and trees discussed by Trask et al. (2007a).

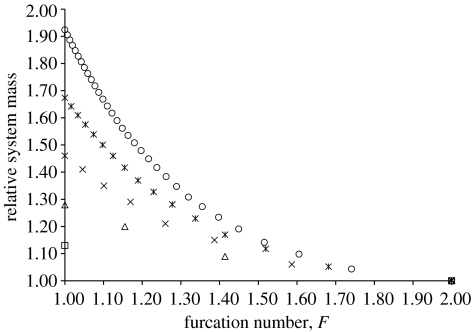

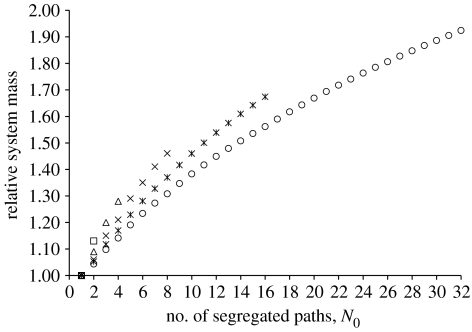

Although an engineering system cannot sacrifice structural material and regrow additional support like a tree, a leak in one section could be manually repaired. A segregated network is likely to be much lighter than wholly redundant systems. A leak could, however, cause the loss of one path and the consequent loss of healing functionality to one region of a structure. Nonetheless, this is a potentially powerful reliability strategy for an engineering system, because the chance of both a failure of the healing system and a critical damage event occurring to the same region of the structure could be engineered to be very small. It is also well suited to a point-to-area network where regions, rather than discrete components, require supply. In order for this to be exploited in engineering design it is necessary to link the degree of redundancy and the associated mass penalty. The cost of selecting a furcation number less than 2 is in fluid flow efficiency. The pressure drop of a fluid flowing through a pipe rises as the fourth power of diameter falls in laminar flow (Sutera & Skalak 1993), so multiple conduits of the same total cross-sectional area will have a greater hydraulic resistance than a single, wide conduit. This will have an implication for the total system mass, which is a key design driver for high-performance applications of self-healing. Thus, the selection of an appropriate value for F will be a compromise of reliability against mass. The relative mass of networks with different furcation numbers was calculated numerically owing to the wide range of variables to consider, and the need for logical operations to ensure a practically realizable network was generated. The approach adopted was to compare the total system mass of a network with each available furcation number with a baseline, bifurcating network with the same number of generations. For each network of n generations, the number of vessels in the most distal generation, Nn, was fixed at 2n since it is assumed that in a practical design this would be chosen to give a certain maximum network density. The number of starting vessels, N0, was altered to give the variation in furcation. A non-integer furcation number will not give an integer number of vessels in every generation, so practically realizable configurations were generated that minimize the mass penalty by delaying the increase in number of vessels until the configuration matched the baseline as closely as possible. This is how the networks in figure 2 were derived. It was assumed that the length of each generation of the baseline network was proportional to the local internal diameter. This is a useful design configuration—and one often found in natural systems—in which the overall mass of each generation has been shown to be constant (Williams et al. 2008). For simplicity these lengths were held constant as the furcation number was varied. Junction losses have been shown to be negligible for highly ‘svelt’ networks of this scale (Lorente & Bejan 2005)—those where the length of each generation greatly exceeds the vessel diameter, for example by a factor of over 30 (Wang et al. 2006). This comparative study is conservative because increasing reliability by selecting a lower furcation number reduces the number of junctions. The relative masses of several networks with unit overall length but different numbers of generations (effectively networks of different density) are shown in figures 3 and 4.

Figure 3.

Mass penalty incurred by segregating networks of various densities (numbers of generations) relative to baseline, fully bifurcating (F=2) networks. Segregation is indicated by reducing furcation number. Each point on each curve shows a decrease in the number of segregated paths from N0=Nn at F=1 to N0=1 at F=2. (Network generations: square, second; triangle, third; cross, fourth; star, fifth; circle, sixth.)

Figure 4.

Mass penalty incurred by segregating networks of various densities (numbers of generations) relative to baseline, fully bifurcating (F=2) networks. Segregation is indicated directly by the number of segregated paths. The number of vessels in the most distal generation limits the number of paths in less dense networks. (Network generations: square, second; triangle, third; cross, fourth; star, fifth; circle, sixth.)

A network with more generations is shown in figure 3 to have more furcation numbers available for selection (more points in the series) because there are more vessels in the most distal generation so more values of NN to substitute into equation (3.7). At a given furcation number, the penalty for segregating the network is larger in more dense networks. However, every point in each series plotted in figure 3 represents an integer number of segregated paths with a single path at F=2 for all series. Therefore, at a given furcation number, a network with more generations has more segregated paths. Furcation number is not, therefore, a simple measure of redundancy and may not be the most intuitive variable for practical system design. It may be more helpful to directly consider the number of separate paths into which a network has been divided. This is simply the number of vessels in the first generation of a network, N0, and is related to mass penalty in figure 4, which shows that a network with higher density (more generations) allows a lower relative mass after segregation, although the absolute mass of the denser network will be higher.

McCulloh et al. (2003) measured values of F approximately 1.45 for plant specimens and figure 3 shows that, albeit for simple and idealized networks, the loss in efficiency that this induces is relatively small, but preserves a relatively large proportion of the network from a single path failure. Figure 4 is a more useful engineering representation, showing that it is relatively inexpensive in overall system mass to segregate the network into four or six zones. The probability of penetrating structural damage and that damage causing a catastrophic leak and a full limit load being applied to the same region of a structure during a mission (i.e. before maintenance can be attempted) requires several coincidental events. In a given application, the degree of segregation, the probabilities of these events occurring and the ease of damage identification would need to be considered to formally calculate the probabilities but the validity of this approach as an alternative to costly full system redundancy is demonstrated. One potential disadvantage of this approach would be an increased susceptibility to blockage failures (group III) due to smaller tubing bores. However, as fluid supply to only one region of the structure would be affected a similar argument to that above, using the probability of several circumstances in the same region, could be invoked. Another practical consideration is the efficient application of pumping to multiple circuits as the analysis does not consider economies of scale in pump design.

3.4 Filtration

Fundamental failure mode III, blockage or constriction, would usually be addressed using filters in an engineering system to remove debris that could block lines or damage components. The inclusion of any filter will incur a mass penalty in two parts: the pumping mass incurred by the hydraulic resistance of the filter and the basic mass of the filter unit. Using electrical resistance as an analogy, the power of a flowing fluid, PF, is given by

| (3.9) |

where Q is the volumetric flow rate and R is the hydraulic resistance. Using the power (PF) to mass (mpump) ratio of the pump, k, and the mass of the filter itself, mfilter, the total mass penalty for providing filtration is given by

| (3.10) |

Thus, the mass penalty is directly proportional to filter resistance, which will increase as the filter resistance increases in service. The traditional engineering approach to filter blockage is to use a filter bypass that opens when the filter blocks. However, this leaves the system without filtration until the filter can be replaced, adds maintenance effort and still requires the pump to be capable of providing a certain flow rate with the filter partially blocked. Nonetheless, a simple filter is a good solution for the identified failure modes. In the human circulatory system, filtration is partly performed by the lungs in which small blood clots and air emboli (bubbles) are collected. The mast cells of the lungs contain a naturally occurring thrombolysin that breaks down clots, effectively functioning as a self-clearing filter. In a self-healing system susceptible to blockage by resin clots, a filter bed that actively removes cured resin could have an advantage over a simple filter by removing the need to size the pump for the partially blocked condition.

3.5 Interconnection

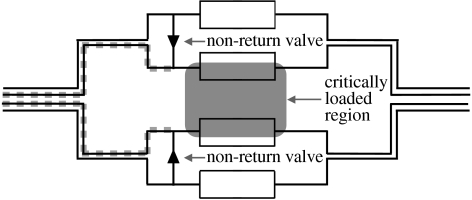

Although system duplication for redundancy is not noted in the human circulatory system, local redundant pathways for arterial supply have evolved consisting of alternative routes for blood flow. Two notable examples of these anastomoses are the circle of Willis in the brain (Gray 2005), the patellar anastomosis around the knee joint (Scapinelli 1968; Gray 2005) and the arterial supply to the hand (Gray 2005). In both cases, the conventional bifurcating network of blood vessels is supplemented by cross-linking vessels that allow flow to be redirected and maintained in the event of blockage, although whether this has evolved as a redundancy or as a form of manifold to pool and distribute flow is unclear (Moore et al. 2005; Okuyamaa et al. 2006). Several engineering studies on self-healing materials (Bejan et al. 2006; Wang et al. 2006; Toohey et al. 2007) have used an interconnected grid of channels which provides extensive redundancy of flow paths because they are effectively porous media. Wechsatol et al. (2005) have studied the use of redundant paths for fluid flow in branching networks; the authors term these ‘loops’. The approach adopted was to provide redundant supplies to every one of many discrete points to protect against blockage of a supply channel. It was shown that an efficiency penalty was incurred over a simple branching network, although the different approach adopted prevents a direct assessment in terms of mass. To avoid confusion with closed-loop and open-loop (circulating and static) self-healing networks, ‘interconnections’ is preferred to loops in this work. Interconnecting branches of a network allows designs that sit between a branching network and a fully interconnected grid to be generated. The approach proposed by Wechsatol et al. (2005) provides interconnections throughout a network at significant cost in flow efficiency. The fact that anastomoses in the arterial supply have evolved in specific locations in the human body suggests an application where this provides an evolutionary advantage, although this may not be purely reliability. Providing unnecessary additional channels in a self-healing material has a cost in terms of mass, compromised structural performance and risk of total fluid loss from a single leak. Biomimetic redundancy suggests providing alternative flow paths selectively where needed and as an alternative to a fully redundant system.

Figure 5 shows an example of using an interconnection in unison with the segregation concept from §3.3 to provide a second supply to a critically loaded area of a structure reliant on self-healing. In this case, a redundant flow path selectively interconnects the inner and outer circuits such that a blockage of either of the inner flow pathways upstream of the critically loaded region of the structure would cause flow transfer from the outer paths (covering the less structurally critical region) to maintain supply to the critical region. A non-return valve would prevent the loss of fluid from the inner systems if the outer ‘donor’ path were punctured (failure group II). However, a fluid leak in the critical path could also cause the loss of the donor flow path. An interconnected system is more susceptible to leakage; however, nature manages this risk using vasoconstriction, blood clotting and, in the major veins, through non-return valves. Bleeding from varicose veins, in which the latter functionality is degraded, can be a clinical concern. The use of flow control devices such as non-return valves assists implementation, even offering the possibility of more complex valves under logic control, which could be considered analogous to vasoconstriction. Interconnections provide a useful tool to balance critical failure groups of leakage (II) and blockage (III) in different regions of a structure. Detailed design selection requires a trade-off of weight penalties and probabilities of failure and impact event. The load on engineering structures typically varies during different phases of use, and the probability of experiencing a peak load during a certain period should be considered. Since the tubes are not expected to carry flow under normal circumstances, the mass penalty is directly related to the size and number of vessels and valves required. Wechsatol et al. (2005) studied the sizing of vessels for various combinations of blocked vessels; a similar approach using a range of failure scenarios could be used to size an interconnecting channel of minimum mass using analysis previously derived (Williams et al. 2008). It is not possible to produce a general mass analysis for this approach, but it is intuitive that inclusion of a limited number of interconnections to address specific risks would be significantly lighter than wholly redundant systems.

Figure 5.

Use of an interconnection (anastomosis) to maintain flow to a structurally critical region of a component in the case of a blockage along the highlighted supply vessels.

3.6 Novel resin systems

The healing agent in the human circulatory system has fewer critical failure modes than the healing agent in the engineering system. Most engineering healing agents used to date have been based on two-phase thermosetting polymerization reactions of engineering resins such as epoxies or dicyclopentadiene that rely on intimate contact or mixing of the resin with a hardener or catalyst. The bleeding mechanism of self-healing does not guarantee this occurrence, although good healing efficiencies have still been achieved (e.g. Kessler et al. 2003; Brown et al. 2005; Rule et al. 2005; Pang & Bond 2005b; Toohey et al. 2007; Williams et al. 2007c). The blood clotting process is initiated by the local absence of endothelial (blood vessel lining) cells in a region of vessel breach. These cells are coated with an enzyme that effectively dissolves clots (Davies & McNicol 1983), such that part of the clotting initiation is in fact by a lack of clotting inhibition. The reaction proceeds via a cascade of reactions with multiple chemical feedback and amplification steps (Davie & Ratnoff 1964; Macfarlane 1964). This mechanism inherently removes one potential mode of failure. Balanced clotting and thrombosis in the system, rather than being a failure, is in fact a feature of human thrombosis and makes for a robust healing system. Trask et al. (2007a) have suggested possible avenues for novel resin systems that could more closely mimic human blood clotting and thereby address both the unfavourable conditions for curing conventional engineering resin systems (failure group V), and prolonging working life (failure group VI). There is also scope for improved, customized formulations of the more traditional engineering resin systems, which could also make the system less sensitive to these modes of failure.

3.7 Fluid renewal and replenishment

Periodic renewal of the circulating fluid is a feature of many engineering and natural fluid systems. This addresses healing agent degradation (group VI) and could enhance the reliability of other components, or allow the substitution of improved fluids developed after the system enters service. The key requirement is access and provision for this task to be performed which will have a small penalty in mass and maintenance cost.

3.8 Summary

A range of reliability solutions have been identified that could address fundamental failure modes in vascular networks for self-healing. Qualitative, and where possible quantitative, estimates of the mass penalty incurred by these strategies have been discussed. This provides a toolkit of reliability approaches for network design in different applications. The reliability improvements discussed in the previous subsections are linked to the fundamental failure modes in table 4 and all are practically realizable in the two currently reported vascular healing approaches. In the case of tubing embedded into a sandwich structure core (Williams et al. 2007c), discrete connecting pieces are available in several forms to join vessels to produce the desired network.

Table 4.

Reliability improvements by failure mode.

| failure mode groups | possible reliability strategies |

|---|---|

| I pump failure | component redundancy (§3.1) |

| monitoring (§3.2) | |

| II leakage | system redundancy (§3.1) |

| monitoring (§3.2) | |

| network segregation (§3.3) | |

| III blockage | network segregation (§3.3) |

| filtration (§3.4) | |

| interconnection (§3.5) | |

| IV failure to bleed | component (riser) redundancy (§3.1) |

| V resin cure conditions | novel resin systems (§3.6) |

| VI resin degradation | monitoring (§3.2) novel resin systems (§3.6) fluid renewal and replenishment (§3.7) |

The analysis in this work has deliberately avoided the effect of the failure of a self-healing system on the structure it protects since the technology is insufficiently mature to consider this effect with confidence, especially as it will be application-specific. The critical failure modes and corresponding reliability strategies suggested are general, which allows for refinement of the assumptions and sensitivity in the criticalities assigned. Detailed design and service experience will provide the data for a more quantitative analysis. This would allow confident selection of specific reliability approaches for a specific application, and where necessary a full engineering trade-off between approaches. Notably there is also scope for applying various approaches to specific areas of a structure in which maintaining self-healing functionality is more critical. These design decisions will be influenced by the performance of the self-healing system and loading and local strength variation in the structure.

Segregation, to protect against leakage, and interconnections, to manage the danger of blockage, directly influence the overall network configuration. In an application in which leakage proved highly improbable but blockage of a vessel supplying a structurally critical region is a concern, a highly interconnected network with locally redundant paths, such as described by Wechsatol et al. (2005) would be desirable. In an extreme case, this would favour an interconnected grid arrangement such as reported by Toohey et al. (2007). Equally, if after further analysis, failure by leakage was found to be critical, a highly segregated network would be the most suitable selection. None of the previously reported vascular networks designs have considered the effects of different failure modes in network design. The overall driver for minimum mass also remains for almost all high-performance applications and is directly analogous to fluid flow efficiency. These considerations can be expressed in the design space shown in figure 6. The network shown in figure 5 sits somewhere in the middle of this design space. As previously discussed, increasing the complexity of a self-healing system would also be expected to increase the manufacturing effort, could degrade structural performance and would increase costs. A design space could be constructed to consider all the effects for different applications, given additional modelling or experimental work. The next logical area for investigation is the influence of the network on the fundamental structural performance. This could be combined with the mass analysis to produce a design space in terms of specific strength (strength per unit mass) or specific stiffness (stiffness per unit mass).

Figure 6.

Design triangle for reliability driven network configuration.

The concept of a segregated network is particularly useful when combined with interconnections, because it encompasses the complete design space between the minimum mass furcating network, the power to manage leakage failures offered by a fully segregated network and negating the effect of blockage using an interconnected grid. This concept is highly biomimetic, taking first the segregation concept from plant vasculature and showing the potential mass advantages over a conventional engineering approach to redundancy. Combining this with an approach seen in animal vasculature, anastomoses, or selective interconnections in the supply path (providing arterial supply to regions such as the brain, knee and hands) gives a new design freedom for network engineers to exploit. Finally, it is interesting to link this engineering tool back to nature. McCulloh et al. (2003) suggested that the leaves of plants had a higher furcation number than the stems because they are effectively disposable, with a lower drive for reliability. Inspection of figure 6 suggests that there is also a mass driver for the higher furcation and engineering instinct suggests that there is a structural advantage for plants in removing mass from the leaves, giving the stability benefit of lowering the overall centre of mass. Whether this driver is evolutionarily significant in relation to the many other factors governing vascular form is unknown.

4. Concluding remarks

The reliability of a proposed self-healing vascular network for engineering applications has been assessed by identifying the critical failure modes via a FMECA. This technique has also been applied to the human circulatory system to gain insight and understanding. Several biomimetic and traditional engineering reliability strategies that address the critical failure modes were discussed, producing a ‘toolkit’ of approaches for use in network design. Discrete approaches include monitoring, filtration, novel resin systems, bespoke formulations of existing engineering resins, periodic fluid renewal and the provision of some redundant components such as pumps or capillaries. These approaches should be considered as part of the overall network design because, for example, the mass penalty of installing duplicate pumps can be reduced by 7% by re-optimizing the supply vessel diameters.

Total system redundancy, in the form of duplex or triplex independent parallel systems, is used extensively in engineering fluid distribution systems although these applications tend to feature point-to-point distribution to discrete components. In natural systems that feature a point-to-area type distribution there is clearly no evolutionary advantage for completely redundant circulatory systems, and it has been shown that total redundancy is likely to be costly in terms of overall power or mass. A combination of strategically placed interconnected flow paths (mimicking the anastomoses of blood supply to various parts of the human body including the brain and hands) and a segregated network concept that is biomimetic of plant vasculature are suggested. These concepts fit within a design triangle that balances reliability against leakage and blockage with the overall driver for minimum system mass. Numerical studies of the mass penalty of a segregated configuration suggest that segregating the network into six independent paths incurs a mass penalty of approximately 25%. Considering reliability as an afterthought in the design of self-healing systems could be potentially costly, and an important conclusion of this work is that system reliability should be considered as an integral part of the basic network configuration. Selection of appropriate approaches for specific applications will require quantitative probability analysis and consideration of the interaction of a self-healing system and the structure that it protects, i.e. an integrated study of reliability, healing performance and tailored network design.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the funding provided for H.R.W. by the University of Bristol through a Convocation Scholarship and the funding provided by the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council under grant numbers GR/TO3390 and GR/T17984. The authors are grateful to Ms Jessica Williams for translating the work reported by Marey et al. (1997). Finally, the authors would like to thank the referees for the improvements suggested to the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Detailed results of failure modes, effects and criticality analysis (FMECA) for human and engineering systems

References

- Abrate S. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 1998. Impact on composite structures. [Google Scholar]

- Bejan A, Lorente S. Constructal theory of generation of configuration in nature and engineering. J. Appl. Phys. 2006;100:041 301. doi: 10.1063/1.2221896. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bejan A, Lorente S, Wang K.-M. Networks of channels for self-healing composite materials. J. Appl. Phys. 2006;100:033 528. doi: 10.1063/1.2218768. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bleay S.M, Loader C.B, Hawyes V.J, Humberstone L, Curtis P.T. A smart repair system for polymer matrix composites. Compos. Part A. 2001;32:1767–1776. doi: 10.1016/S1359-835X(01)00020-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- British Standards Institute. British Standards Institute; London, UK: 1991. BS5760 reliability of systems, equipment and components. Guide to failure modes, effects and criticality analysis (FMEA and FMECA) Part 5. [Google Scholar]

- Brown E.N, White S.R, Sottos N.R. Microcapsule induced toughening in a self-healing polymer composite. J. Mater. Sci. 2004;39:1703–1710. doi: 10.1023/B:JMSC.0000016173.73733.dc. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown E.N, White S.R, Sottos N.R. Retardation and repair of fatigue cracks in a microcapsule toughened epoxy composite—part II: in situ self-healing. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2005;65:2474–2480. doi: 10.1016/j.compscitech.2005.04.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Dam M.A, Ono K, Mal A.K, Shen H, Nutt S.R, Wudl F. A thermally re-mendable cross-linked polymeric material. Science. 2002;295:1698–1702. doi: 10.1126/science.1065879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S.H, Andersson H.M, White S.R, Sottos N.R, Braun P.V. Polydimethylsiloxane-based self-healing materials. Adv. Mater. 2006;18:997–1000. doi: 10.1002/adma.200501814. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coles G, Fuller B, Nordquist K, Kongslie A. Using failure mode effects and criticality analysis for high-risk processes at three community hospitals. Joint Comm. J. Q. Patient Safety. 2005;31:132–140. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(05)31018-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies K.A, McNicol G.P. Haemostasis and thrombosis. In: Weatherall D.J, Ledingham J.G.G, Warrel D.A, editors. Oxford textbook of medicine. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 1983. ch. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Davie E.W, Ratnoff O.D. Waterfall sequence for intrinsic blood clotting. Science. 1964;145:1310–1312. doi: 10.1126/science.145.3638.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson D.R, Cieslicki K, Gu X, Barber R.W. Biomimetic design of microfluidic manifolds based on a generalised Murray's law. Lab on a chip. 2006;6:447–454. doi: 10.1039/b516975e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray H. In: Anatomy of the human body. 20th edn. Lewis W.H, editor. Lea & Febiger; Philadelphia, PA: 1918. [Google Scholar]

- Gray H. In: Gray's anatomy: the anatomical basis of clinical practice. 39th edn. Standring S, editor. Elsevier; Edinburgh, UK: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.A, Zhang W, Branthwaite M, Jones F.R. Self-healing of damage in fibre-reinforced polymer–matrix composites. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2007;4:381–387. doi: 10.1098/rsif2006.0209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones A.S, Rule J.D, Moore J.S, Sottos N.R, White S.R. Life extension of self-healing polymers with rapidly growing fatigue cracks. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2007;4:395–403. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2006.0199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamphaus J.M, Rule J.D, Moore J.S, Sottos N.R, White S.R. A new self-healing epoxy with tungsten (VI) chloride catalyst. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2008;5:95–103. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2007.1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler M.R, White S.R. Self-activated healing of delamination damage in woven composites. Compos. Part A. 2001;32:683–699. doi: 10.1016/S1359-835X(00)00149-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler M.R, White S.R, Sottos N.R. Self-healing structural composite materials. Compos. Part A. 2003;34:743–753. doi: 10.1016/S1359-835X(03)00138-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Lorente S, Bejan A. Vascularised materials: tree-shaped flow architectures matched canopy to canopy. J. Appl. Phys. 2006;100:063525. doi: 10.1063/1.2349479. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lorente S, Bejan A. Sveltness, freedom to morph, and constructal multi-scale flow structures. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2005;44:1123–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2005.08.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Macfarlane R.G. An enzyme cascade in the blood clotting mechanism, and its function as a biochemical amplifier. Nature. 1964;202:498–499. doi: 10.1038/202498a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marey A, Coupez B, Gruca L, Vannier V, Renom P, Wibaut B, Rugeri L, Cossement C, Cosson A. Outcome of a quality approach for transfusion safety on prescription, circuit improvement and blood product marking out. Example of CHRU, Lille [Impact d'une demarche qualite en securite transfusionnelle sur la prescription, l'optimisation des circuits, la tracabilite: experience du CHRU de Lille] Transfus. Clin. Biol. 1997;4:469–484. doi: 10.1016/S1246-7820(97)80065-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCulloh K.A, Sperry J.S, Adler F.R. Water transport in plants obeys Murray's law. Nature. 2003;421:939–942. doi: 10.1038/nature01444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCulloh K.A, Sperry J.S, Adler F.R. Murray's law and the hydraulic vs mechanical functioning of wood. Funct. Ecol. 2004;18:931–938. doi: 10.1111/j.0269-8463.2004.00913.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Milsum J.H, Roberge F.A. In: Foundations of mathematical biology. Supercellular systems. Rosen R, editor. vol. 3. Academic Press; New York, NY: 1973. p. 74. [Google Scholar]

- Moore S.M, Moorhead K.T, Chase J.G, David T, Fink J. One-dimensional and three-dimensional models of cerebrovascular flow. J. Biomech. Eng. 2005;127:440–449. doi: 10.1115/1.1894350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray C.D. The physiological principle of minimum work. I. The vascular system and the cost of blood volume. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1926;12:207–214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.12.3.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuyamaa S, Okuyamaa J, Okuyamaa J, Tamatsub Y, Shimadab K, Hoshic H, Iwaid J. The arterial circle of Willis of the mouse helps to decipher secrets of cerebral vascular accidents in the human. Med. Hypotheses. 2006;63:997–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2003.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang J.W.C, Bond I.P. ‘Bleeding composites’—damage detection and repair using a biomimetic approach. Compos. Part A. 2005a;36:183–188. doi: 10.1016/j.compositesa.2004.06.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pang J.W.C, Bond I.P. A hollow fibre reinforced polymer composite encompassing self-healing and enhanced damage visibility. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2005b;65:1791–1799. doi: 10.1016/j.compscitech.2005.03.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S.M, Allaire P.E, Wood H.G, Throckmorton A.L, Tribble C.G, Olsen D.B. Methods of failure and reliability assessment for mechanical heart pumps. Artif. Organs. 2005;29:15–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2004.29006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson M.O.W, Wisheart M.J. Review of low-velocity impact properties of composite materials. Compos. Part A. 1996;27:1123–1131. doi: 10.1016/1359-835X(96)00074-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rule J.D, Brown E.N, Sottos N.R, White S.R, Moore J.S. Wax-protected catalyst microspheres for efficient self-healing materials. Adv. Mater. 2005;17:205–208. doi: 10.1002/adma.200400607. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scapinelli R. Studies on the vasculature of the human knee joint. Acta Anat. 1968;70:305–331. doi: 10.1159/000143133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutera S.P, Skalak R. The history of Poiseuille's law. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 1993;25:1–19. doi: 10.1146/annurev.fl.25.010193.000245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tomblin, J., Lacy, T., Smith, B., Hooper, S., Vizzini, A. & Lee, S. 1999 Review of damage tolerance for composite sandwich airframe structures. Report no. DOT/FAA/AR-99/49, Federal Aviation Authority, USA, pp. 1–61.

- Toohey K.S, Sottos N.R, Lewis J.A, Moore J.S, White S.R. Self-healing materials with microvascular networks. Nat. Mater. 2007;6:581–585. doi: 10.1038/nmat1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trask R.S, Bond I.P. Biomimetic self-healing of advanced composite structures using hollow glass fibres. Smart Mater. Struct. 2006;15:704–710. doi: 10.1088/0964-1726/15/3/005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trask R.S, Williams H.R, Bond I.P. Self-healing polymer composites: mimicking nature to enhance performance. Bioinspir. Biomim. 2007a;2:1–9. doi: 10.1088/1748-3182/2/1/P01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trask R.S, Williams G.J, Bond I.P. Bioinspired self-healing of advanced composite structures using hollow glass fibres. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2007b;4:363–371. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2006.0194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K.-M, Lorente S, Bejan A. Vascularized networks with two optimized channel sizes. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2006;39:3086–3096. doi: 10.1088/0022-3727/39/14/031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsatol W, Lorente S, Bejan A. Tree-shaped networks with loops. Int. J. Heat Mass Tran. 2005;48:573–583. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2004.08.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- White S.R, Sottos N.R, Geubelle P.H, Moore J.S, Kessler M.R, Sriram S.R, Brown E.N, Viswanathan S. Autonomic healing of polymer composites. Nature. 2001;409:794–797. doi: 10.1038/35057232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams G.J, Trask R.S, Bond I.P. A self-healing carbon fibre reinforced polymer for aerospace applications. Compos. Part A. 2007a;38:1525–1532. doi: 10.1017/j.compositesa.2007.01.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, H. R., Trask, R. S. & Bond, I. P. 2007b Design of vascular networks for self-healing sandwich structures. In First Int. Conf. on Self-healing Materials, Noordwijk aan Zee, The Netherlands, 18–20 April 2007.

- Williams H.R, Trask R.S, Bond I.P. Self-healing composite sandwich structures. Smart Mater. Struct. 2007c;16:1198–1207. doi: 10.1088/0964-1726/16/4/03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams H.R, Trask R.S, Weaver P.M, Bond I.P. Minimum mass vascular networks in multifunctional materials. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2008;5:55–65. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2007.1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zako M, Takano N. Intelligent material systems using epoxy particles to repair microcracks and delamination in GFRP. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 1999;10:836–841. doi: 10.1106/YE1H-QUDH-FC7W-4QFM. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zapanta C.M, Snyder A.J, Weiss W.J, Cleary T.J, Reibson J.D, Rawhouser M.A, Lewis J.P, Pierce W.S, Rosenberg G. Durability testing of a completely implantable electric total artificial heart. Am. Soc. Artif. Int. Organs J. 2005;51:214–223. doi: 10.1097/01.mat.0000159385.32989.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Detailed results of failure modes, effects and criticality analysis (FMECA) for human and engineering systems