To the Editor: Green and colleagues1 claim to have provided evidence that unconscious (implicit) race bias among physicians is causally associated with fewer recommendations for appropriate thrombolytic treatment for African-American male patients who present with symptoms suggestive of acute coronary syndromes. We attempt to demonstrate why this claim is not substantiated.

From a sample of 776 internal medicine and ED residents, Green and colleagues obtained data from 220 who were unaware of the purpose of the study or who were not otherwise excluded. They were shown a vignette about a 50-year-old man with a history of hypertension and smoking who presented to the ED with chest pain. With the vignette the face of a white or black man of approximately age 50 was randomly paired. The vignette was written to be consistent with the presentation of myocardial infarction, in particular containing an EKG reading that was “suggestive of anterior myocardial infarction.” The subject was told he/she did not have access to a cardiac catheterization lab and that the patient had no absolute contraindications to thrombolysis.

Subjects were asked to a) assess the likelihood that the patient’s pain was due to CAD using a five-point scale where 1 = very unlikely (< 20%), 5 = very likely (>80%); b) state “yes” or “no” to “would you recommend thrombolysis” for this patient; c) state the strength of that recommendation on a five-point scale from 1 = would definitely recommend to 5 = would definitely NOT recommend; and d) give their opinion about the effectiveness of thrombolysis for acute MI on a five-point scale from 1 = very ineffective to 5 = very effective.

Subjects then completed three implicit association tests (IATs) to “measure bias that may not be consciously recognized.” The “IAT measures the time it takes subjects to match members of social groups (e.g., blacks and whites) to particular attributes (e.g., good, bad, cooperative, stubborn).” A difference in reaction times to associate good or bad concepts with black or white faces is the measure of “implicit bias.”

We obtained opinions from content experts to develop plausibility arguments and consulted published literature to critique the methods and results of Green et al. Nine attending-level general internists plus two disparities researchers (one nephrologist, one pulmonary-critical care physician) reviewed the study scenario [A] without a patient face [B] and were blinded to the published study and its results. (Letters in brackets refer to the Appendix where details of the bases for the critiques are presented.) The internists provided opinions about the top 5 diseases in their differential diagnosis (DDx), estimated a probability for each disease in the DDx (adding to 100%), and stated their opinion as to whether thrombolysis would be beneficial (+), neutral (0), or harmful (-) (90 mm visual analog scale) for each of the diseases in their DDx (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Physicians’ Estimated Probability of Alternative Diagnoses and the Judgment as to Whether Thrombolysis would have a Beneficial, Neutral, or Harmful Effect if the Alternative Diagnosis were Correct

| CAD | Musc/Skel | GERD | PE | Pericarditis | Pneumonia/pleuritis | Aortic dissect. | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physician N | 11 | 9* | 8* | 7* | 6* | 4* | 4 | 6 |

| Average probability | 42% | 16% | 22% | 9% | 6% | 18% | 6% | 14% |

| Benefit (+) | 10 (+) | 5(+) | --- | |||||

| Neutral (0)† | 1 (0) | 2 (0) | 3 (0) | 2 (0) | ||||

| Harmful (-) | 6 (-) | 4 (-) | 1 (-) | 5 (-) | 1 (-) | 4 (-) |

CAD = coronary artery disease. Musc/Skel = muscular/skeletal disorder. GERD = gastroesophageal reflux disease. PE = pulmonary embolism.

*One physician in these columns provided probability data but did not provide data on benefits or harms

†Neutral was (+/-) 15mm from the scale midpoint

Five major areas of concern were identified: 1) the design of the judgment task response set provided no opportunity for subjects (resident physicians) to list competing diagnoses. No differential diagnoses were solicited, nor was there a recording of the risks/benefits of thrombolytic therapy for the competing diagnoses, e.g., pericarditis or dissecting aortic aneurysm [C]; 2) main study results were based on an interpretation of cross-sectional data as if the data were longitudinal (see Fig. 1) [D]; 3) although randomization was performed by allocating a white or black face randomly with each scenario, a non-randomized variable (IAT score) was interpreted as if it had been the unit of randomization [E]; 4) Green et al. conflated measurement issues with interpretation; the progression from the Introduction through the Methods to the Results section of the terms “increasing time for association,” “racial preference,” “racial bias,” to “pro-white/pro-black scores” does not represent a sequence of synonyms [F]; and 5) no serious discussion of alternative hypotheses occurred [G].

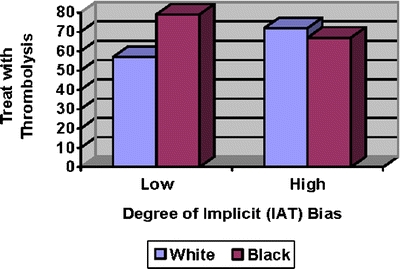

Figure 1.

Relationship between physician race preference Implicit Association Test (IAT) score and thrombolysis decision as a function of patient’s race. This figure is based upon Figure 3d in Green et al. Higher numbers on the y-axis denote greater propensity of recommending thrombolysis.

The figure contains the same data as Green et al.’s Figure 3d, which purports to summarize the prejudicial impact of the “pro-white bias” on thrombolytic treatment of patients. The basis for the conclusion in Green et al. is the significant “decrease” (p < .05) in the thrombolytic treatment of black patients and the “increase” (p < .11) in the thrombolytic treatment of white patients as “implicit bias” increases. The resulting interaction was significant (p = .009).

The figure depicts an extremely unusual state of affairs in which those with the lowest levels of bias as assessed by the IAT treat the races differently, and the most biased physicians treat the races nearly equivalently. This pattern would seem to be contrary to what most observers would consider to be a manifestation of bias.

We offer an interpretation of the data that differs from that offered by Green et al. First, we are reluctant to deem as implicitly biased those persons on the right-hand side of the figure who treat the races equivalently. Our unwillingness to rely on the measure of bias utilized by Green et al. is also motivated by the fact that those physicians who are supposedly least biased are the ones who treat patients differently as a function of patient race. We respectfully suggest that this general pattern is completely contrary to the way in which “bias” is generally construed.

Concern 1 (no competing diagnoses) is a fatal flaw as it does not allow the investigators to have any criterion from which to declare the treatment choice to be appropriate or inappropriate (the “delta scores” are uninterpretable). African-Americans are more likely than whites to present with symptoms that strongly mimic coronary disease even in the absence of significant coronary obstruction on angiography2. Our sample of physicians indicated that thrombolysis would be harmful if pericarditis or aortic dissection were the actual disease entity. We suggest that this flaw and other methodological shortcomings (see Appendix) nullify the conclusion that “unconscious (implicit) race bias among physicians” predicts the inappropriate under-utilization of thrombolytic therapy among African-American male patients (and thus does not support the predictive validity of “implicit bias”); nor is the claim “that physicians’ unconscious biases may contribute to racial/ethnic disparities in use of medical procedures such as thrombolysis for myocardial infarction” supported.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to Dana R. Carney for providing us with the four data points from Figure 3d in Green et al.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

Appendix

[A] Some advantages and disadvantages of the scenario:

The use of the scenario has the advantage of standardizing the materials presented to subjects and allows the independent variable to be manipulated between the experimental groups. (In the current study, the proposed moderating variable, black or white face, was used for randomization rather than the primary independent variable, IAT score.)

The use of the scenario has the disadvantage of not allowing the individuation of information3,4 that may be important to diagnosis (e.g., other risk factors that may affect the illness presentation and the distribution of prior probabilities across diseases in the differential diagnosis) or treatment selection (e.g., prior access to care, preferences, beliefs).

[B] When considering the differential diagnosis of a given case of chest pain, does the presence of a black or white face associated with the vignette provide clinically important information?

We believe the answer is “yes.”

If the scenario were to be used by itself (without faces), one is asked, in essence, to estimate the likelihood of diseases for the average 50-year-old man with hypertension who is a smoker.

With the addition of white and black faces (which in this study were morphed to be an “average” white or black man), the task becomes a bit more specific. One is asked to either estimate the likelihood of diseases for the average 50-year-old black man with hypertension (HT) who is a smoker or for the average 50-year-old white man with HT who is a smoker.

Rates of coronary heart disease CHD prevalence and outcomes in the US vary with race, age, gender, and other factors.

Data from the population based National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) survey suggest that CHD rates are lower for black men in the US population5

- Disproportionate coronary heart disease mortality exists for African-American men and women2

- Earlier age at onset of CHD

- Higher overall CHD mortality

- Higher out of hospital death rate

- Higher sudden cardiac death rate

Data from a recent study from one state (1984–1993) documents decreased CHD mortality rates for white men generally and for black men in the highest SES category but not for other black men6.

[C] The cognitive process for identifying CHD (weighing information for diagnosis and prognosis) can be quite challenging and may need to be somewhat different for black and white patients. The diagnostic testing literature has long acknowledged the phenomenon of a given symptom having different diagnostic outcomes in cogent subsets of patients. An obvious example is the frequency with which coronary artery disease will be found among patients with substernal chest pain when one subgroup is young women and the other is old men. This phenomenon has been labeled “spectrum”7.

In support of the likelihood of a spectrum effect, a recent paper that summarizes literature about coronary heart disease in African-Americans2 states the following:

The predictive value of most conventional risk factors for CHD is similar for blacks and whites. However,

- Risk of death and other sequelae attributable to hypertension are greater for African-Americans.

- In African-Americans hypertension develops at younger ages and is associated with 3 to 5 times higher cardiovascular mortality rate than whites.

- African-Americans appear to experience greater cardiovascular and renal damage than whites at any level of blood pressure.

More African-Americans than whites smoke but tend to consume fewer cigarettes per day.

African-Americans are more likely than whites to present with symptoms that strongly mimic coronary disease even in the absence of significant coronary obstruction on angiography.

- Although issues such as socioeconomic status, access to cardiovascular care, and patients’ health seeking behaviors all contribute to clinical outcomes, recent advances in our understanding of the pathophysiology of acute coronary events also provide insights into biological similarities and differences in the spectrum of clinical presentations and outcomes for African-Americans and whites.

- Extent of underlying coronary atherosclerosis

- Plaque instability

- Degree of inflammation

- Microembolization

- Type and extent of thrombus formation

- Degree of endothelial dysfunction and coronary vasospasm

Does it matter that the subjects were asked to provide only the likelihood of CHD instead of a differential diagnosis?

The answer is clearly “yes.”

Diagnostic uncertainty8 and levels of tolerance for uncertainty9,10 have been linked to variations in physicians’ diagnoses, testing patterns, and treatment choices.

In the face of uncertainty about a given diagnostic possibility, the decision to recommend a given therapy should not be based solely on the likelihood of the disease for which the therapy is a reasonable recommendation (i.e., the treatment decision is not solely a function of the likelihood of the primary disease). The decision-maker must also consider whether this same therapy might cause harm if the diagnosis were an entity other than the diagnosis currently considered as being most likely.

How low the probability of the alternative disease(s) must be to warrant using the therapy being considered will depend, among other things, on how harmful the considered treatment would be if the alternative diagnostic possibility is the disease causing the presenting symptoms. Even if the CHD probability were judged to be very high (>85%), thrombolysis would be best avoided if the use of thrombolysis were associated with a high likelihood of fatality in the alternative condition (e.g., aortic dissection or pericarditis).

[D] Data on the primary independent variable, all the covariates, and the dependent variable were collected at only one point in time (cross-sectional data collection). Within the two arms of the study, post-randomization subgroups were formed based on levels of the subjects’ implicit association test (IAT) scores. The authors were thus comparing two subgroups selected from each study arm (see E, below). The values of the IAT scores for each subject did not change. Despite the cross-sectional nature of the data collection, the authors perform regression analyses, connect the point estimates in each study arm (black or white scenario), and discuss “increases” in “pro-white implicit bias.” Cross-sectional data support associations but not causal claims.

[E] Once the subjects who had been randomized into each arm of the study (by black face/white face allocation) were subsequently partitioned by IAT levels, are the sub-groups within each arm still comparable?

We don’t know.

IAT scores have been partitioned into two parts, low and high, and represent two groups of resident subjects. These groupings are no longer the two groups randomized to black and white faces with the vignette but are now clustered by their IAT results. The IAT scores do not “change” between the “high” and “low” groups being compared but are present in differing amounts in the different residents who form the two new groups. Since IAT scores (the putative “causal agent”) were not randomly allocated among the residents, and since the groups being compared have been constructed based on a non-random characteristic, we no longer can hold the expectation that the two groups will be similar in measured and unmeasured covariates.

For example, let’s say we randomly allocated black and white faces associated with a vignette with the purpose of creating two groups with approximately equal heights. With a sufficiently large sample, we could reasonably expect similar height distributions in each arm of the study (since randomization provides the basis for the expectation for– but not the guarantee of–similar distributions of measured and unmeasured covariates in each arm).

If we then separated the subjects in each arm into shorter and taller subgroups, we can no longer have the same expectation that other covariates, e.g., gender and weight, will be equivalently distributed. The similar distributions of height in the original (randomized) groups may occur due to an admixture of taller women (and thus relatively heavier than shorter women) and shorter men (and thus relatively lighter than taller men) in one group and an admixture of both women and men of medium heights in the other group. This would create a potential problem for interpreting results that may be associated with gender (and perhaps weight) if we neglected to record sex or measure weights in the sample. (In comparing the taller with taller subjects and shorter with shorter subjects across the arms of the trial, we would be comparing taller/heavier women with medium height/weight men and shorter/lighter men with medium height/weight women.)

[F] Separating the “news from the views” (personal communication, Alvin Feinstein, 1986) – In the Background section, the IAT methodology is introduced as hypothesizing that subjects will match a group representative to an attribute more quickly if they connect these in their minds and is quantified as the “difference in average matching speeds for opposite pairings.” These are reasonable characterizations of the method and measurement issues. The Methods section should continue the theme of measurement related issues. In this section “differences in average matching speed” are characterized as “implicit race preference” and “pro-white” and “problack bias.” These latter terms are repeated in the Results section. In the place and time in which we live, these terms are not synonyms for “differences in average matching speed” and would have been more appropriately placed in the Comment section of the paper.

[G] The Comment section of the paper reiterates the findings, discusses why prior criticisms of IAT may not apply, discusses how the findings seem to fit a broader societal picture of implicit race biases, speculates about how a study done on residents may apply to physicians generally, and devotes two sentences to limitations. No alternative hypotheses for the findings are offered or discussed.

In the closing paragraph, the authors suggest that physicians may harbor “unconscious...stereotypes that influence clinical decisions.” In doing so, it seems the authors have confused prior probabilities with stereotypes. Webster’s New Collegiate Dictionary defines stereotype as “something conforming to a fixed or general pattern, especially a standardized mental picture that is held in common by members of a group that represents an over simplified opinion, affective attitude, or uncritical judgment.” In contradistinction to this definition, a prior probability is not a static picture, but a dynamic decision-making feature that is based on the information available at a given point in time. The estimate will change with the introduction of clinically important information, e.g., age, sex, health related habits, and comorbid diseases as in the current scenario based study. Spectrum effects (discussed in C, above) may alter the degree to which a given piece of evidence shifts the estimated probability of disease for the leading diagnosis and its competitors.

Contributor Information

Neal V. Dawson, Email: nvd@case.edu

Hal R. Arkes, Phone: +1-614-2921592, FAX: +1-614-6883984, Email: Arkes.1@osu.edu

References

- 1.Green AR, Carney DR, Pallin DJ, et al. Implicit bias among physicians and its prediction of thrombolysis decisions for black and white patients. JGIM. 2007;22:1231–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Clark LT, Ferdinand KC, Flack JM, et al. Coronary heart disease in African-Americans. Heart Disease. 2001;3:97–108. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Betancourt JR, Carrillo JE, Green AR. Hypertension in multicultural and minority populations:Linking communication to compliance. Curr Hypertens Rep. 1999;1:482–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Platt FW, Gaspar DL, Coulehan JL, et al. “Tell me about yourself:” The patient-centered interview. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:1079–85. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Gillum RF, Mussolino ME, Madans JH. Coronary heart disease incidence and survival in African-American women and men: The NHANES I epidemiologic follow-up study. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:111–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Barnett E, Armstrong AL, Casper ML. Evidence of increasing coronary heart disease mortality among men of lower social class. Ann Epidemiol. 1999;9:464–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Ransohoff DF, Feinstein AR. Problems of spectrum and bias in evaluating the efficacy of diagnostic tests. N Engl J Med. 1978;299:926–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.McGuire TG, Ayanian JZ, Ford DE, Henke REM, Rost KM, Zaslavsky AM. Testing for statistical discrimination by race/ethnicity in panel data for depression treatment in primary care. Health Serv Res. 2008;43:531–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Geller G, Tambor ES, Chase GA, Holtzman NA. Measuring physicians’ tolerance for ambiguity and its relationship to their reported practices regarding genetic testing. Med Care. 1993;31:989–1001. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Allison JJ, Kiefe CI, Cook EF, et al. The association of physician attitudes about uncertainty and risk taking with resource use in a Medicare HMO. Med Decis Making. 1998;18:320–9. [DOI] [PubMed]