Abstract

Background

Few data have evaluated the relationship between caregiving and cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk.

Objective

The purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence and predictors of caregiver strain and to evaluate the association between caregiving and CVD lifestyle and psychosocial risk factors among family members of recently hospitalized CVD patients.

Design and Participants

Participants in the NHLBI Family Intervention Trial for Heart Health (FIT Heart) who completed a 6-month follow-up were included in this analysis (n = 263; mean age 50 ± 14 years, 67% female, 29% non-white).

Measurements

At 6 months, standardized information was collected regarding depression, social support, and caregiver strain (high caregiver strain = ≥7). Information on lifestyle risk factors, including obesity, physical activity, and diet, were also collected using standardized questionnaires. Logistic regression models on the association between caregiving and CVD risk factors were adjusted for significant confounders.

Results

The prevalence of serving as a CVD patient’s primary caregiver or caring for the patient most of the time was 50% at 6 months. Caregivers (primary/most) were more likely to be women (81% vs 19%, p < .01), married/living with someone (p < .01), >50 years old (p < .01), have ≤ high school education (p < .01), be unemployed (p < .01), get less physical activity (p < .01), and have a higher waist circumference (p < .01) than non-caregivers (some/occasional/none). Mean caregiver strain scores were significantly higher among those with depressive symptoms (p < .01) and low social support (p < .01) in a multivariable adjusted model.

Conclusions

Caregivers of cardiac patients may be at increased risk themselves for CVD morbidity and mortality compared to non-caregivers due to suboptimal lifestyle and psychosocial risk factors.

KEY WORDS: cardiovascular disease, caregiver, prevention, depression

BACKGROUND

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death in the United States, and nearly 2,500 Americans die from CVD daily1. Development of CVD gives rise to significant physical and emotional difficulties in affected individuals, resulting in reduced quality of life. Most CVD deaths are preventable with lifestyle behaviors, such as physical activity, diet, and weight management. Finding ways to increase adherence to CVD prevention goals is a critical research area.

Caregivers who are primarily responsible for the welfare of a loved one with CVD may be at increased risk for heart disease themselves. The act of caregiving has recently been identified as an independent risk factor for CVD morbidity and mortality 2. Caregivers often exhibit depressive symptoms and obesity; they also may have little time to partake in preventive health measures for themselves3. Emotional distress has been shown to increase as caregiver burden increases in individuals caring for stroke patients4. Some research shows that caregiving is associated with poorer social support and can be a major barrier to exercise5. Poor family support is an indicator of adverse health outcomes for caregivers6.

Previous research has shown that gender differences may exist in the amount of distress that caregivers feel, with women reporting more distress7. Luttik et al. found that women also reported feeling a lack of family support as part of caregiver burden more times than men8. It is also important to determine the underlying mechanisms that may cause caregivers to be at increased risk for CVD, such as lifestyle or psychosocial factors, so that appropriate interventions can be developed and tested.

The purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence and predictors of caregiving and caregiver strain, and to evaluate the associations between caregiving and CVD lifestyle and psychosocial risk factors in a diverse population of family members and/or spouses of patients hospitalized with CVD. We tested the hypothesis that primary caregivers of patients with CVD would have greater psychosocial and lifestyle risk factors than non-caregivers.

METHODS

Design and Subjects

Participants in the Family Intervention Trial for Heart Health (FIT Heart) who completed a baseline and 6-month follow-up visit were included in this analysis (n = 263; mean age 50 ± 14 years, 67% female, 29% non-white). Briefly, FIT Heart is a 1-year randomized controlled clinical trial among family members of patients hospitalized with CVD at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Columbia University Medical Center campus between 2005 and 2007. The purpose of FIT Heart was to test the effectiveness of a hospital-based standardized screening and educational intervention to increase adherence to national CVD prevention goals.

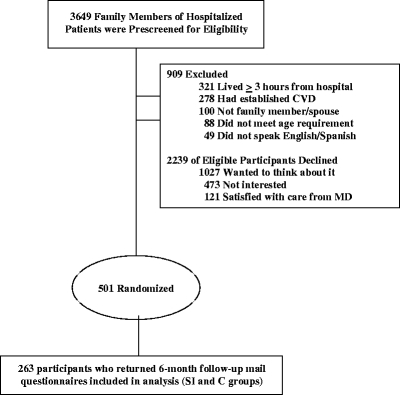

The study population consisted of adult family members and spouses of diagnosed cardiac patients who were recruited at the time of hospitalization of the family member for coronary heart disease (Fig. 1). The cardiac patients themselves were not involved in the study. English and Spanish-speaking men and women between the ages of 20–79 were eligible. Participants must not have had any established CVD, diabetes, active liver disease, or chronic kidney disease. All participants were required to give informed consent, and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Columbia University Medical Center. Bilingual staff members were available to assist participants, and all forms were available in English and Spanish. We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during this research.

Figure 1.

FIT heart participants from prescreening through 6-month analysis.

Caregiving and Caregiver Strain

Caregivers were defined in this study as family members providing assistance and care for loved ones who have been hospitalized for CVD. Caregiving was assessed by self-reported answer to the question, “To what extent were you involved in the post-hopitalization care (such as assistance with daily activities, doctor visits, and/or medication) for the family member who was hospitalized at New York-Presbyterian Hospital when you enrolled in the FIT Heart study?” Answer choices were: primary caregiver, cared for the patient most of the time, cared for the patient some of the time, cared for the patient occasionally, and not involved in post-hospitalization care for the patient. Caregivers were grouped as primary/most vs. some/occasionally/none.

The Caregiver Strain Index9, a brief, easily administered instrument used to identify strain among spouses and family who provide varying degrees of care to recently hospitalized cardiac patients, was administered to all subjects at 6 months. Internal consistency for this instrument is acceptable (Chronbach’s alpha = 0.86). Construct validity is supported by correlations with the physical and emotional health of the caregiver and with subjective views of the caregiving situation. The range for scoring on this index is 0–13, and a score of 7 or higher indicates a high level of caregiver strain. The Caregiver Strain Index consists of a list of items that people providing care to adults have found to be difficult, such as disturbed sleep, physical strain, family adjustments, changes in personal plans, emotional adjustments, time demands, upsetting behavior, and financial strain. The Caregiver Strain Index was developed with a sample of 132 caregivers providing assistance to recently hospitalized older adults with a variety of conditions and is appropriate for caregivers of any age10.

Depressive Symptoms

Level of depressive symptoms was assessed by the Beck Depression Inventory, second edition (BDI- II)11. This 21-item self report instrument for measuring the severity of depression in adults is the most widely used self-report measure of depression (over the past 2 weeks) for clinical and normal patients. Respondents are asked to endorse the most characteristic statements covering the time frame of the past 2 weeks, consistent with the DSM-IV criteria for major depression. The BDI-II is scored by summing the ratings for the 21 items. Each item is rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 to 3, and total scores range from 0 (no depression) to 63 (severe depression). Comprehensive reviews on the applications and psychometric properties on the BDI in both clinical and non-clinical populations have reported its high reliability, regardless of clinical population12,13. This instrument has demonstrated adequate reliability both in terms of internal consistency and stability. Coefficient alphas ranging from .73–.92 have been reported for non-psychiatric populations12. This instrument has also demonstrated strong convergent and discriminant validity.

ENRICHD Social Support Inventory

Social support was measured using the ENRICHD Social Support Inventory (ESSI), a seven-item, self-report measure used in the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Patients (ENRICHD) trial14. The ESSI was chosen for use in this study because of its high test-retest reliability, good convergence with standard emotional support measures, and its link to cardiac outcomes. The ESSI is derived of items from well-validated scales, such as the Perceived Social Support Scale15, that have been used in previous studies14. Internal consistency for the ESSI, using Cronbach’s α, is 0.88. The intra-class correlation coefficient is 0.94, reflecting excellent reproducibility16.

The ESSI is also recommended for use when a short screening instrument is desired, as in the case of this study. To qualify as having low social support, patients must have had a score of ≤2 on at least two of five (items 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6) items, and a total score of ≤18.

Lifestyle Measures

Each participant completed a standardized questionnaire including demographic data (i.e., age, gender, race/ethnicity, household income, education) and lifestyle habits such as smoking status.

Physical Activity

Physical activity information was assessed at baseline using standardized questions that have been adapted from the Behavioral Risk Factor Survey and validated. The questions elicited information about the frequency (number of days per week) and duration (number of minutes per day) that participants engaged in physical activity.

Dietary Assessment

Adherence to the Adult Treatment Panel (ATP) III Therapeutic Lifestyle Change (TLC) diet (<7% of calories from saturated fat, <30% of calories from total fat, and <200 mg dietary cholesterol/day) was assessed using the MEDFICTS dietary assessment tool previously validated in this population of family members of cardiac patients17. The MEDFICTS questionnaire consists of eight food categories: meats, eggs, dairy, fried foods, fat in baked goods, convenience foods, fats added at the table, and snacks18. Scores range from 0 to 216 points, and a score of <40 indicates a diet low in saturated fat. Saturated fat as a percentage of total daily caloric intake was assessed using the Gladys Block Food Frequency Questionnaire 1998, a validated food frequency questionnaire developed by Block Dietary Systems, Berkeley, CA.

Risk Factor Guideline Adherence

Trained health-care professionals performed standardized cardiometabolic risk factor screenings including height, weight, BMI, waist circumference, and saturated fat intake. Following the screening, participants were randomized to a stage of change-matched special intervention (SI), including individualized counseling and education from a prevention counselor or a control group. SI subjects were taught lifestyle approaches to risk reduction based upon national CVD prevention guidelines19.

Body Composition

Height and weight were measured by standard protocol, and BMI was calculated directly by the formula: weight (kg)/height (m)2. Overweight was defined as BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m2, and obesity was defined as BMI ≥30 kg/m2 in accordance with national guidelines20,21. Increased waist circumference was defined as >35 inches in women and >40 inches in men20,21.

Lipids, Glucose, and High Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein

Lipids (total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL-cholesterol), glucose, high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), and lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 (Lp-PLA2) were evaluated from venous blood drawn from all participants at baseline and after a 6–12 h fast. Determination of lipids, glucose, and hsCRP was performed on blood collected and stored at −70° up to 2 weeks and analyzed in the Columbia University CTSA Biomarker Laboratory. The Centers for Disease Control lipid quality control program certifies the Columbia University CTSA Biomarker Laboratory. Plasma total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and glucose were determined spectrophotometrically on a Hitachi 912 chemical analyzer, and plasma LDL-cholesterol was assessed using a direct measurement assay. Serum hsCRP was assessed in the CTSA Biomarker Laboratory using the Diagnostic Systems Laboratories, Inc., ultra-sensitive CRP enzyme-linked immunoabsorbent assay (ELISA).

Data Management and Statistics

All data were collected on standardized forms at baseline and 6 months later and double entered into a Microsoft Access database, then exported to SAS software (version 9.1, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) for purposes of statistical analysis. Categorical data were presented as frequencies and percentages. Continuous data were presented as means and standard deviations. Comparisons across groups were made using the chi-square test for categorical data and t-tests and linear regression for continuous data. The bivariate analysis for comparing caregivers to non-caregivers was conducted using simple chi-square analysis. Regression equations were calculated with each of the risk factors (i.e., waist circumference, saturated fat intake) as dependent variables and caregiving as a potential predictor variable. Models were adjusted for potential confounders including age, gender, marital status, and baseline levels of depression and social support. Variables with significant contributions to the model were retained in the regression equation. Statistical significance was set at p < .05.

RESULTS

The characteristics of the 263 subjects included in the analysis are listed in Table 1. The mean age was 50 ± 14 years and ranged from 20 to 78 years, with 29% being non-white and two-thirds (67%) being female. Waist circumference, BMI, physical activity level, smoking status, and saturated fat intake data were available on 263 participants with mean levels presented in Table 1. Mean values for CVD risk factors assessed exceeded optimal levels for BMI, waist circumference, and saturated fat intake as a percentage of calories per day. Mean physical activity levels were not at goal for most participants (at least 3 days per week, 30 min per session).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants

| (N = 263) | |

|---|---|

| Characteristic | N (%) |

| White | 186 (71%) |

| Female | 175 (67%) |

| > High school education | 215 (83%) |

| Employed/student | 191 (73%) |

| Married/living with someone | 176 (67%) |

| No health insurance | 31 (12%) |

| Current cigarette smoker | 20 (8%) |

| Depression (BDI score ≥10) | 78 (31%) |

| Low social support [defined as ≤2 on at least 2 out of the 5 questions (question 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6) and a Total Social Support score ≤18 on the ESSI] | 28 (11%) |

| Mean ± SD | |

| Age | 50 ± 14 |

| Saturated fat as a percentage of daily caloric intake | 11 ± 3 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27 ± 6 |

| Waist circumference-female (inches) | 34 ± 5 |

| Waist circumference-male (inches) | 38 ± 5 |

| Physical activity days/week | 2 ± 2 |

| Physical activity minutes/day | 28 ± 31 |

Note: BDI = Beck Depression Inventory, ESSI = ENRICHD Social Support Instrument

The prevalence of caregiving and caregiver burden is shown in Table 2. As demonstrated, the prevalence of serving as a CVD patient’s primary caregiver was 39% at 6 months; 11% of participants reported caring for the patient most of the time, 32% some of the time or occasionally, and 18% none of the time. Additional psychosocial information was obtained at 6 months on 101 participants and is also presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Prevalence of Caregiving, Caregiver Strain, and Psychosocial Risk Factors, Overall and by Gender

| Overall | Gender | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 263 | Female | Male | |

| Caregiving (any) | 212 (82%) | 149 (70%) | 63 (30%) |

| Caregiving (primary/most) | 129 (50%) | 104 (81%) | 25 (19%) |

| Caregiving (some/occasionally/none) | 130 (50%) | 67 (52%) | 63 (48%) |

| Mean caregiver strain score | 2.4 ± 3 | 2.5 ± 3 | 2.2 ± 3 |

| High caregiver strain (score ≥7) | 28 (12%) | 19 (68%) | 9 (32%) |

| Depressive symptoms-baseline (N = 263) | 78 (31%) | 60 (77%) | 18 (23%) |

| Depressive symptoms-6 months (N = 101) | 18 (19%) | 12 (67%) | 6 (33%) |

| Low social support-baseline (N = 263) | 28 (11%) | 18 (64%) | 10 (36%) |

| Low social support-6 months (N = 98) | 9 (9%) | 5 (56%) | 4 (44%) |

Note: Depression defined as ≥10 on the Beck Depression Inventory; low social support defined as ≤2 on at least 2 out of the 5 questions (question 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6), and a total social support score ≤18 on the ENRICHD Social Support Inventory

The caregiver profile is shown in Table 3. Caregivers (primary/most) were more likely to be women (81% vs 19%, p < .01), married/living with someone (p < .01), >50 years old (p < .01), have ≤ high school education (p < .01), be unemployed (p < .01), and have a higher waist circumference (p < .01) than non-caregivers (some/occasional/none). High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) was not significantly different in the two groups.

Table 3.

Univariate Associations Between CVD Risk Factors, Caregiving, and Caregiver Strain

| Caregiving (primary/most vs. some/occasionally/none) | Caregiver strain (continuous score) | |

|---|---|---|

| OR (p-value) | OR (p-value) | |

| Age (>50 vs. ≤50) | 2.99 (<.0001) * | .967 (.43) |

| Gender (male vs. female) | .26 (<.0001)* | .975 (.58) |

| Ethnicity (racial/ethnic minority vs. white) | 1.27 (.39) | 1.050 (.26) |

| Education (≤ high school vs. > high school) | 2.65 (.004)* | 1.068 (.19) |

| Employment (unemployed vs. employed/student) | 2.14 (.007)* | .992 (.86) |

| Married/living with someone (no vs. yes) | .32 (<.0001)* | 1.006 (.89) |

| Smoking (yes vs. no) | .40 (.06) | .994 (.94) |

| Physical activity: minutes/day (≤30 min vs. >30 min) | 2.39 (.001)* | 1.092 (.07) |

| Physical activity: days/week (≤3 days vs. >3 days) | 1.36(.31) | 1.141 (.03)* |

| BMI (≥30 vs. <30) | 1.33 (.31) | .896 (.10) |

| Waist circumference (>40 vs. ≤40 inches male, >35 vs. ≤35 inches female) | 2.33 (.002)* | 1.125 (.006)* |

| Blood pressure (120/80: high vs. low) | .85 (.52) | 1.011 (.80) |

| Depression at baseline (yes vs. no) | 1.69 (.05) | 1.171 (.0004)* |

| Depression-6 month (yes vs. no) (N = 101) | 2.28 (.13) | 1.305 (.005)* |

| Low social support at baseline (yes vs. no) | 1.41 (.41) | 1.172 (.007)* |

| Low social support-6 month (yes vs. no) (N = 98) | .48 (.33) | 1.115 (.32) |

| Hs-CRP [(3, 10) vs. (0, 3)] | 1.07 (.80) | 1.025 (.59) |

| LDL cholesterol (≥130 vs. <130) | .87 (.60) | 1.114 (.01)* |

*Significant at p < .05

Univariate associations between caregiver strain and risk factors for CVD are shown in Table 3, and they included physical activity (p = .019), BMI (p = .02), waist circumference (p < .01), LDL-cholesterol (p = .01), depression both at baseline and 6 months (p < .01), and social support at baseline (p < .01). Table 4 shows that significant mean differences between those experiencing high levels of caregiver strain compared to those experiencing low levels of strain were found for saturated fat percentage (p = .04), MEDFICTS score (p = .001), glucose (p = .005), and LDL particle number (p = .02). Table 5 shows that those experiencing high caregiver strain also had a higher BMI (p = .01) and a higher percentage of saturated fat intake (p = .05) in a multivariable model adjusted for confounders at baseline.

Table 4.

Differences Between CVD Risk Factor Values for Participants with High Caregiver Strain and Those Without

| Caregiver strain (high vs. low) | |

|---|---|

| Mean difference (p-value) | |

| t-test | |

| Age | 49 vs. 50 (.86) |

| Carbon monoxide | 2.00 vs. 2.85 (.22) |

| Physical activity minutes/day | 17 vs. 29 (.05) |

| Physical activity days/week | 1.02 vs. 2.00 (.001)* |

| Body mass index | 30 vs. 27 (.01)* |

| Waist circumference | 36.7 vs. 34.9 (.11) |

| Blood pressure-systolic | 127.5 vs. 126.2 (.69) |

| Blood pressure-diastolic | 78.7 vs. 76.9 (.46) |

| BDI score baseline | 11.54 vs. 6.79 (.002)* |

| BDI score-6 month (N = 101) | 10 vs. 5 (.04)* |

| Total social support score baseline | 19 vs. 22 (.001)* |

| Total social support score-6 month (N = 98) | 18.86 vs. 21.68 (.11) |

| hsCRP | 3.29 vs. 2.92 (.55) |

| LpPLA2 | 198 vs. 189 (.47) |

| LDL cholesterol | 130 vs. 117 (.05) |

| HDL cholesterol | 56 vs. 61 (.24) |

| Total cholesterol | 212 vs. 200 (.12) |

| Triglycerides | 131 vs. 112 (.16) |

| Glucose | 107 vs. 98 (.005)* |

| LDL particle number | 1,317 vs. 1,149 (.02)* |

| Percentage of saturated fat intake | 11.5 vs. 10.5 (.04)* |

| MEDFICTS score | 64 vs. 45 (.001)* |

*Significant at p < .05

Table 5.

Multivariable Linear Regression Model for the Effect of Caregiver Strain on Risk Factors for CVD

| Predictors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver strain adjusted by age, gender, and marital status | Caregiver strain adjusted by base model plus baseline depression or social support | |||

| Outcomes | β value | (p-value) | β value | (p-value) |

| Physical activity | −.98 | (.02)* | −.82 | (.049)* |

| BMI | 2.88 | (.01)* | 1.93 | (.1) |

| Depression baseline | 4.58 | (.002)* | 3.01 | (.023)* |

| Depression 6 months | 5.17 | (.05) | 1.22 | (.51) |

| Social support score baseline | −2.75 | (.0007)* | −1.74 | (.02)* |

| LDL particle number | 172.39 | (.02)* | 139.33 | (.05) |

| Percent saturated fat intake | .97 | (.048)* | .84 | (.10) |

| MEDFICTS score | 18.14 | (.003)* | 18.52 | (.002)* |

*Significant at p < .05

A mediational analysis between increased caregiver strain and elevated BMI revealed that the relationship between the two was significantly attenuated by depression level (Table 6). Depression is significantly related to both BMI and caregiver strain. BMI and caregiver strain are also significantly associated. With the addition of depression to the model between caregiver strain and BMI, the beta coefficient changed from .355 to .237. This change represents a greater than 15% change, suggesting that depression mediates the relationship between overweight/obesity and caregiver strain. No significant associations were found for other potential mediators tested, including social support and physical activity.

Table 6.

Mediational Analysis of Caregiving, BMI, and Depression

| BMI | Caregiver strain score | |||

| Beta = .36 | P < .0001 | |||

| Depression | Caregiver strain score | |||

| Beta = .63 | P < .0001 | |||

| BMI | Depression | |||

| Beta = .17 | P < .0001 | |||

| BMI | Caregiver strain score | Depression | ||

| Beta = .28* | P = .049 | Alpha = .18 | P = .0006 | |

*Change in beta is greater than 15%; BMI = body mass index

DISCUSSION

The main findings of this study are that cardiac caregivers may be at increased risk for CVD morbidity and mortality due to lifestyle and psychosocial risk factors. Caregiving is frequent among family members of patients recently hospitalized with CVD and is associated with several common CVD risk factors, including age, lower education, unemployment, less physical activity, and increased waist circumference. Those with increased caregiver strain also had significantly higher levels of saturated fat intake, depression, BMI, and lower levels of social support, which may further increase CVD risk. Our analysis also suggests that the relation between caregiver strain and obesity is mediated through depression. These findings are potentially important as efforts to reduce CVD risk among caregivers may be enhanced if they include dimensions of psychosocial health, such as depression, stress, and social for caregivers. Our data do not suggest a primary role of inflammation as a mechanism through which caregiving increases CVD risk.

In this study, among those who provided primary caregiving, the overwhelming majority were women. This is consistent with previous research documenting that over half the women in the US will care for an ill family member at some point in their lives20,21. We found that caregivers were three times as likely to be married and less than half as likely to have greater than high school education than non-caregivers. Similarly, other studies have observed caregivers to have low education levels and a high likelihood of being married22. Such data underscore the importance of having appropriate educational materials (e.g., below 7th grade reading level) for caregivers.

We found that caregivers and those with higher caregiver strain were more likely to follow lifestyle patterns not in agreement with CVD risk factor goals and more likely to have psychosocial risk factors assessed by standardized instruments. Similar to our results, caregiving has been linked to risk factors for CVD including elevated blood pressure23 and depression24. In a prospective study of caregivers and risk of coronary heart disease from the Nurse’s Health Study cohort, high levels of caregiving burden increased the risk for clinical CHD among women (RR, 1.82; 95% confidence interval, 1.08–3.05)25. Our data suggest that depression may be an important risk factor among female caregivers, which could explain an elevated risk of clinical CVD. Cardiac patients’ adjustment to their illness is best when spouses or partners are less depressed or anxious than the patients, and worse when spouses or partners are more depressed or anxious than the patients, suggesting that interventions targeted toward positively affecting the psychosocial state of spouses or family members (who are often caregivers) may improve the health of the cardiac patient as well26.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the relation between cardiac caregivers and inflammatory risk factors for CVD. Vitaliano et al. conducted a study of spousal caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and found no link between caregiving and C-reactive protein27. Similarly, we did not document an association between caregivers of cardiac patients and inflammatory risk factors for CVD, suggesting that more traditional risk factors such as obesity are likely in the causal pathway for caregiving and increased risk of CVD. We showed that obesity is likely a significant mediating factor and the root cause may be depression leading to overeating28. Adding to the biological plausibility of this finding is that physical activity levels were reduced among those with caregiver strain, which could contribute to overweight and obesity. Decreased physical activity has been previously linked to increased body weight and depression29.

Strengths of this study are its ethnically diverse sample of randomized participants, its prospective nature, and systemic collection of traditional and novel risk factors for CVD. Our study also has important limitations in interpreting the findings. One limitation of the present study is that physical activity data were obtained by self-report, which may have led to skewing of physical activity levels. However, this is unlikely to be systemic and would likely bias our results to the null hypothesis. In addition, there may be gender bias in reporting caregiving responsibilities, which may overestimate prevalence rates in women and underestimate prevalence rates in men or vice versa. A third limitation is that the measurement of all risk factors in this study first occurs when a loved one is hospitalized for cardiac disease. It is not possible to ascertain if family members experienced depression and lack of social support prior to their family members’ hospitalization. Also, since we evaluate caregiving and caregiver strain among individuals that had a family member or friend recently hospitalized with an acute CVD event or revascularization procedure, the results may not generalize to those providing long-term chronic caregiving.

In conclusion, we showed that caregiving and caregiver strain are associated with traditional and lifestyle risk factors for CVD, and that the relation between caregiving and CVD risk may be mediated through increased depression leading to obesity. Caregivers represent an important population to reach out to, and interventions designed to improve caregiver health should consider mental health and depression, in an effort to optimize the preventive care of the cardiac caregiver.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by a National Institute of Health (NIH) Research Project Award to Dr. Mosca (R01 HL 075101-01A1). This work was supported in part by the NIH-funded General Clinical Research Center at Columbia University, a NIH Research Career Award to Dr. Mosca (K24 HL076346-01A1), and a NIH research training grant to Drs. Aggarwal and Christian (T32 HL007343-27).

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

References

- 1.American Heart Association. Heart and stroke statistical update. Retrieved March 19, 2008 from http://www.americanheart.org.

- 2.Lee S, Colditz G, Berkman L, Kawachi I. Caregiving to children and grandchildren and risk of coronary heart disease in women. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(11):1939–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Vitaliano PP, Scanlan JM, Zhang J, Savage MV, Hirsch IB, Siegler IC. A path model of chronic stress, the metabolic syndrome, and coronary heart disease. Psychosom Med. 2002;64(3):418–35. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Singh M, Cameron J. Psychosocial aspects of caregiving to stroke patients. Axone. 2005;27(1):18–24. [PubMed]

- 5.Harralson TL, Emig JC, Polansky M, Walker RE, Cruz JO, Garcia-Leeds C. Un Corazón Saludable: factors influencing outcomes of an exercise program designed to impact cardiac and metabolic risks among urban Latinas. J Community Health. 2007;32(6):401–12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.McCullagh E, Brigstocke G, Donaldson N, Kalra L. Determinants of caregiving burden and quality of life in caregivers of stroke patients. Stroke. 2005;36(10):2181–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Karmilovich SE. Burden and stress associated with spousal caregiving for individuals with heart failure. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs. 1994;9(1):33–8. [PubMed]

- 8.Luttik ML, Jaarsma T, Veeger N, Tijssen J, Sanderman R, van Veldhuisen DJ. Caregiver burden in partners of Heart Failure patients; limited influence of disease severity. Eur J Heart Fail. 2007;9(6–7):695–701. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Robinson BC. Validation of a caregiver strain index. J Gerontol. 1983;38(3):344–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Sullivan T. Caregiver strain index. Dermatol Nurs. 2004;16(4):385–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory Manual 2. Boston, MA: Harcourt, Brace; 1996.

- 12.Beck AT, Steer RA, Garbin MG. Psychometric properties of the beck depression inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 1988;8:77–100. [DOI]

- 13.Steer RA, Beck AT, Garrison B. Applications of the beck depression inventory. In: Sartorius N, Ban TA, eds. Assessment of Depression. New York: Springer-Verlag; 121–142.

- 14.Berkman LF, Blumenthal J, Burg M, Carney RM, Catellier D, Cowan MJ, Czajkowski SM, DeBusk R, Hosking J, Jaffe A, Kaufmann PG, Mitchell P, Norman J, Powell LH, Raczynski JM, Schneiderman N. Effects of treating depression and low perceived social support on clinical events after myocardial infarction: the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Patients (ENRICHD) Randomized Trial. Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Patients Investigators (ENRICHD) JAMA. 2003;289(23):3106–16. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Blumenthal JA, Burg MM, Barefoot J, Williams RB, Haney T, Zimet G. Social support, type A behavior, and coronary artery disease. Psychosom Med. 1987;49(4):331–40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Vaglio J Jr, Conard M, Poston WS, O’Keefe J, Haddock CK, House J, Spertus JA. Testing the performance of the ENRICHD Social Support Instrument in cardiac patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;13(2):24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Mochari H, Gao Q, Mosca L. Validation of the MEDFICTS dietary assessment questionnaire in a diverse population. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008; In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Kris-Etherton P, Eissenstat B, Jaax S, Srinath U, Scott L, Rader J, Pearson T. Validation for MEDFICTS, a dietary assessment instrument for evaluating adherence to total and saturated fat recommendations of the national cholesterol education program Step 1 and 2. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101:81–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–421. [PubMed]

- 20.Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults. The evidence report. National Institutes of Health. Obes Res. 1998;6(Suppl 2):51S–209S. [PubMed]

- 21.Moen P, Robison J, Fields V. Women’s work and caregiving roles: a life course approach. J Gerontol. 1994;49(4):S176–86. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Pinto RA, Holanda MA, Medeiros MM, Mota RM, Pereira ED. Assessment of the burden of caregiving for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2007;10(11):12402–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Shaw WS, Patterson TL, Ziegler MG, Dimsdale JE, Semple SJ, Grant I. Accelerated risk of hypertensive blood pressure recordings among Alzheimer caregivers. J Psychosom Res. 1999;46(3):215–27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: the caregiver health effects study. JAMA. 1999;282(23):2215–9, Dec 15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Lee S, Colditz GA, Berkman LF, Kawachi I. Caregiving and risk of coronary heart disease in U.S. women. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24(2):113–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Moser DK, Dracup K. Role of spousal anxiety and depression in patients’ psychosocial recovery after a cardiac event. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(4):527–32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Vitaliano PP, Persson R, Kiyak A, Saini H, Echeverria D. Caregiving and gingival symptom reports: psychophysiologic mediators. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(6):930–8, Nov–Dec. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Jirik-Babb P, Norring C. Gender comparisons in psychological characteristics of obese, binge eaters. Eat Weight Disord. 2005;10(4):e101–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Sanchez A, Norman GJ, Sallis JF, Calfas KJ, Rock C, Patrick K. Patterns and correlates of multiple risk behaviors in overweight women. Prev Med. 2007;46(3):196–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]