Abstract

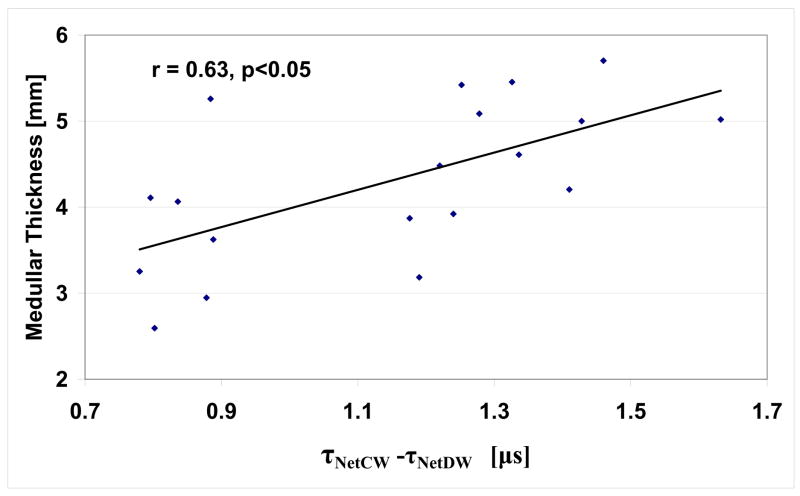

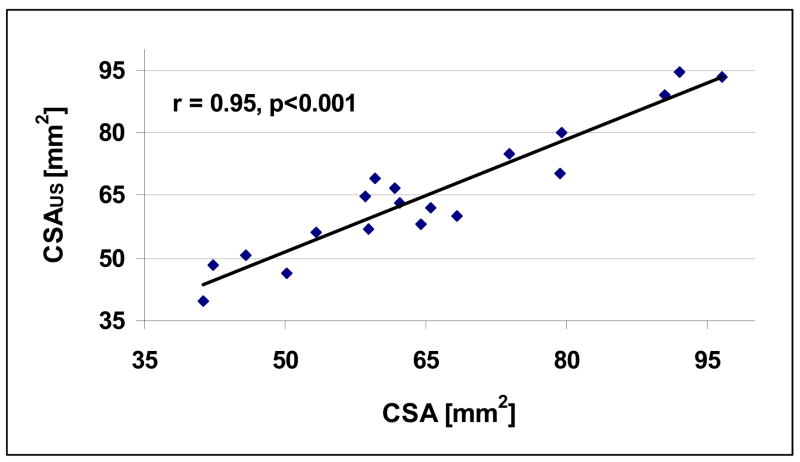

The overall objective of this research is to develop an ultrasonic system for non-invasive assessment of the distal radius. The specific objective of this study was to examine the relationship between geometrical features of cortical bone and ultrasound measurements in vitro. Nineteen radii were measured in through transmission in a water bath. A 3.5 MHz rectangular (1 cm × 4.8 cm) single element transducer served as the source and a 3.5 MHz rectangular (1 cm × 4.8 cm) linear array transducer served as the receiver. The linear array consisted of 64 elements with a pitch of 0.75 mm. Ultrasound measurements were carried out at a location that was 1/3 of the length from the distal end of each radius, and two net time delay parameters, τNetDW and τNetCW, associated with a direct wave (DW) and a circumferential wave (CW), respectively, were evaluated. The cortical thickness (CT), medullar thickness (MT) and cross-sectional area (CSA) of each radius was also evaluated based on a digital image of the cross-section at the “1/3” location. The linear correlations between CT and τNetDW was r = 0.91 (p<0.001) and between MT and τNetDW - τNetCW was r = 0.63 (p<0.05). The linear correlation between CSA and a non-linear combination of the two net time delays, τNetDW and τNetCW, was r = 0.95 (p<0.001). The study shows that ultrasound measurements can be used to non-invasively assess cortical bone geometrical features in vitro as represented by cortical thickness, medullar thickness and cross-sectional area.

Keywords: osteoporosis, ultrasound, radius, cortical thickness, cross-sectional area, net time delay

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a significant health problem affecting more than 20 million people in the U.S. and more than 200 million worldwide [Anonymous, 2001]. Osteoporosis is defined as the loss of bone mass with a concomitant disruption in microarchitecture, leading to an increased risk of fracture [Kanis, 2002]. The most common osteoporotic fractures occur at the wrist, spine, and hip. Hip fractures have a particularly negative impact on morbidity. Approximately fifty percent of those individuals suffering a hip fracture never live independently again [Miller, 1978]. Currently, there are about two hundred thousand hip fractures yearly in the U.S. and approximately one million worldwide [Anonymous, 2001; Melton, 1988]. The aging of the worldwide population is expected to increase the incidence of hip and other fractures as well [Anonymous, 2001].

The primary method for diagnosing osteoporosis and associated fracture risk relies on bone densitometry to measure bone mass [Kaufman and Siffert, 2001]. The use of bone mass is based on the well-established thesis that bone strength is strongly related to the amount of bone material present and that a stronger bone in a given individual is associated generally with a lower fracture risk [Johnell et al. 2005]. Radiological densitometry, which measures the (areal) bone mineral density (BMD) at a given site (e.g., hip, spine, forearm) is currently the accepted indicator of bone strength and fracture risk [Johnell et al. 2005; Blake and Fogelman 2003]. Clinically, this is often done using dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA), which measures the BMD in units of g/cm2 [Bonnick 2004].

Notwithstanding the fact that x-ray methods are useful in assessing bone mass and fracture risk, osteoporosis remains one of the largest undiagnosed and under-diagnosed diseases in the world today [Anonymous, 2001]. Among the reasons for this is that densitometry (i.e., DXA) is not a standard tool in a primary care physician’s office. This is due to its expense and inconvenience, and reticence among patients concerning x-ray exposure, particularly in young adults and children.

Ultrasound has been proposed as an alternative to DXA to estimate fracture risk. This is because it is non-ionizing, relatively inexpensive, and simple to use. Moreover, since ultrasound is a mechanical wave and interacts with bone in a fundamentally different manner than X-rays, it may be able to provide additional information on bone strength, for example aspects related to trabecular architecture [Siffert and Kaufman, 2007; Haïat et al. 2007; Le Floch et al., 2008]; however the ability of ultrasound to provide such “additional information” has not been clinically established and is at present a somewhat controversial subject [Glüer 2007].

Ultrasound measurements for bone assessment have previously been made at a number of anatomical sites, the primary ones being the calcaneus, the phalanges and the radius [Njeh et al. 1999]. However, whereas the former to anatomical sites have relied on through transmission measurements, the radial data has been obtained in an axial configuration, in which the ultrasound is propagated along the long axis of the bone [Bossy et al. 2004]. This has the advantage of needing access to only one side of the limb, but the technique may have some limitations in clearly separating material from geometric properties. However, recent in vitro and simulation results have demonstrated the potential for estimating cortical thickness [Moilanen et al. 2007a; Moilanen et al. 2007b].

The radius has a number of advantages as compared with other anatomical sites, however. They are (i) the availability of extensive data from decades of assessment with x-ray absorptiometry [Bonnick 2004]; (ii) the correlation of radial bone mass with osteoporotic fracture risk [Miller et al. 2002; Siris et al. 2006]; and (iii) the extremely convenient nature of the forearm for measurement. If there is one disadvantage is that it is not as predictive of future hip fracture as measurements of bone mass at the hip itself [Cummings et al. 1993].

The objective of this paper is to develop a new ultrasound technique for assessing bone geometrical properties at the radius. The specific goal is to determine the relationship of parameters derived from ultrasound measurements to geometrical features of cortical bone of the radius in vitro.

Materials and Methods

Bone Samples and Mass Measurements

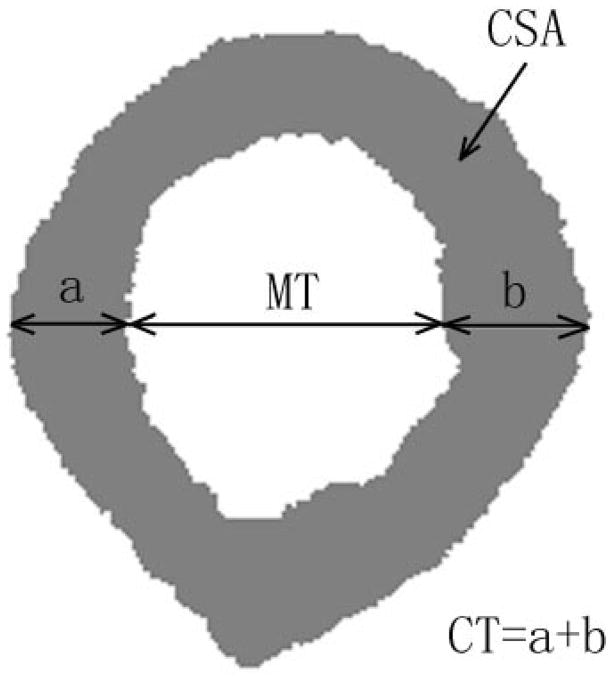

Nineteen human radii of unknown origin were obtained from a commercial supplier (Skulls Unlimited International, Oklahoma City, OK, USA). To assess geometrical features, the radii were analyzed as follows. First, the length of each radius was measured and cut at a distance one-third of the length from the distal end. This location is close to the “1/3rd” location used in x-ray densitometric scanning of the forearm; however the 1/3rd location is defined clinically based on the length of the ulna, which was not available in these experiments [Bonnick 2004]. The proximal surface of the cut end of each radius was coated with black ink and imaged with a digital camera. This portion of the radius is composed of 99% cortical bone with only 1% being cancellous [Bonnick 2004]. The image was converted to a binary one using simple thresholding that separated the cortical bone from the medullar space and the outer surroundings, and each cross-section was image processed to obtain the cortical thickness (CT), medullar thickness (MT) and cross-sectional area (CSA) of bone. CT was defined as the sum of the average cortical thicknesses of the posterior (denoted as “a”) and anterior (denoted by “b”) cortices, respectively. The average cortical thickness of the posterior and anterior cortices was defined as the average of the posterior and anterior cortical thickness over a 1 mm wide region that was manually located to be approximately midway of the cavity with respect to its medial and lateral extent (Fig. 1). The medullar thickness was defined as the average length between the posterior and anterior endosteal surfaces over the same 1 mm region. The cross-sectional area was computed by counting the number of bone pixels and multiplying by the area of one pixel (4.2×10−3 mm2/pixel).

Fig. 1.

Illustration of the cortical bone parameters on the cross-section of a radius (sample R5). For this radius, the CT = 4.12 mm,, MT = 5.09 mm and CSA = 41.3 mm2.

Ultrasound Measurements

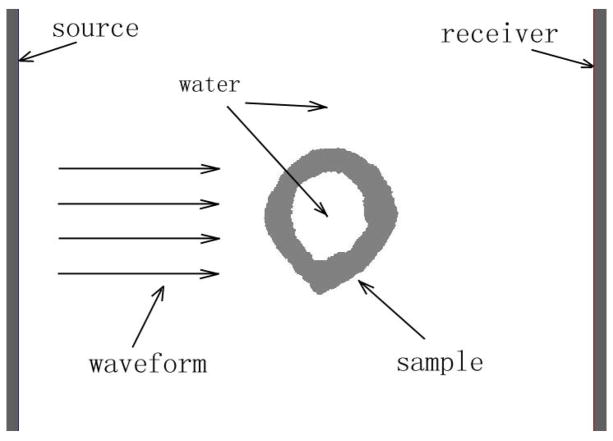

Bench-top measurements were conducted on each of the nineteen radii. A through transmission experimental configuration was utilized (Fig. 2). The source was a single element rectangular 1 cm × 4.8 cm transducer with a center frequency of 3.5 MHz and 60% bandwidth (Valpey Fisher Corporation, Hopkinton, MA, USA). The center frequency and bandwidth were selected as a compromise between sufficient temporal resolution to resolve the signal components (obtained with higher center frequency and bandwidth) and sufficient signal-to-noise ratio (obtained with lower center frequency so that absorption is not too large). This was determined by trial and error using ultrasound simulation [Kaufman et al. 2008a]. A water tank served to conduct the source pulse to the radial sample and receiver. The temperature of the water bath was not controlled but measured to be between 20.6°C and 22.8°C. This variation was not expected to be a significant source of variation because of the fact that differences of propagation times were used as described in a subsequent paragraph. The receiver was a linear array having 64 elements with a nominal center frequency of 3.5 MHz, a 60% bandwidth, and a pitch of 0.75 mm for an overall size of 1 cm by 4.8 cm (Vermon, Tours, France). The receiver and source transducers were linearly co-aligned, both were unfocused, and were 3.8 cm apart. The radius was positioned between the source and receiver so that the ultrasound impinged on it approximately at the “1/3” cross-section; the placement was actually a few millimeters proximal to the cut end in order to reduce edge effects. The edge effects are related to the ultrasound wave impinging on the cut end of the bone, which of course would not be present in clinical measurements. The cross-section of the radius shown in Fig. 2 (sample number “R5”) has a CT = 4.12 mm, MT = 5.09 mm and CSA = 41.3 mm2. The length of the source and receiver (4.8 cm) was chosen to ensure that the array signals would include propagation through a water-only path (i.e., the soft-tissue only path between the radius and ulna in the clinical case) as well as signals propagating through the radius.

Fig. 2.

A schematic of the ultrasound through-transmission set-up.

A pulser (Model No. 5077PR, Panametrics Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) provided input excitation to the source transducer. The 64 channels of the receiver were multiplexed down to two under computer control via a USB connection; the multiplexer also provided amplification that allowed either 0 dB, 30 dB or 50 dB gain to each channel independently, also under computer control (Techen, Inc., Milford, MA, USA). The received waveform from each channel was sampled at 50 MHz with 14 bits resolution using a dual-channel digitizer card (Model No. ATS460, AlazarTech, Inc., Kirkland, Quebec, Canada) installed in an extension chassis (Model No. CB1F, Magma, San Diego, CA, USA). The data was downloaded to a laptop via a PC card, where an averaged waveform based on 64 acquisitions for each of the 64 channels was computed and the 64 averaged signals associated with the array were then stored for further processing.

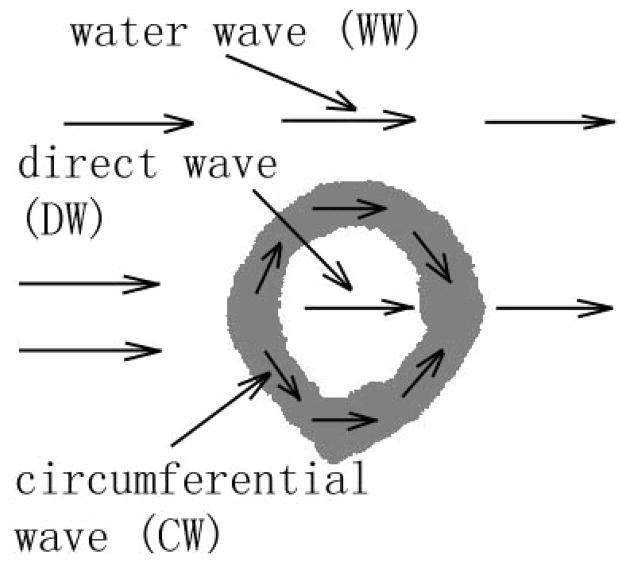

Each ultrasound data set (i.e., the sixty-four averaged time-domain waveforms) was processed to obtain two net time delay parameters associated with each radius. Each of the two parameters are associated with two distinct wavefronts arising from two pathways that the ultrasound propagates along in a given radius, shown schematically in Fig. 3. The first pathway is associated with a direct wave (DW) and is one which propagates from the source to the near cortical surface, through the near cortex, into the medullar cavity, into the far cortex and out the far cortical surface where it propagates to the receiver. The second pathway is associated with a circumferential wave (CW) and is one which also propagates from the source to the near cortical surface and into the near cortex as well, but then remains within the cortex as it “circumferentially” propagates within the bone cortex until it emerges at the far cortical surface and again propagates to the receiver. The circumferential wave is hypothesized to be a guided wave, analogous to Lamb waves in a water-loaded plate [Rose 1999]. However, the relatively broad range of wavelengths (~ 1 to ~ 4 mm) together with the irregular shape of the radius makes the analysis of the actual mode(s) of propagation extremely difficult. Also indicated on Fig. 3 is a path of a wave that has propagated entirely through water (WW), the arrival time of which is used in the computation of the two net time delay parameters.

Fig. 3.

A schematic illustration of the three pathways associated with a propagating waveform: a direct wave (DW), a circumferential wave (CW), and a water wave (WW). See text for additional details.

The first net time delay parameter, τNetDW, is defined to be the difference between the time of travel, τWW, of an ultrasound signal that has propagated through water-only and the time of travel, τDW, of an ultrasound signal that has propagated along the direct pathway (with the transducer separation assumed to be the same in both instances). On the other hand the second net time delay parameter, τNetCW, is defined to be the difference between the time of travel of the water-wave, τWW, and the time of travel, τCW, of an ultrasound signal that is associated with the circumferential pathway (again, with the transducer separation assumed to be the same in both instances). Therefore,

| (1) |

and

| (2) |

We shall see in the Results section that the DW and CW arrive at sufficiently distinct times so that their individual arrival times can be estimated. Arrival time in this study was defined as the time of occurrence of the second peak of each of the three signals, that is the times of occurrence of the second peak of the WW, DW and CW. As will be seen in the following paragraphs, the waveforms associated with each of the three paths of propagation have first a negative going cycle followed by a positive going cycle; the times at which these positive cycles reach their maximum values is defined to be the times of arrival of the WW, DW and CW, respectively.

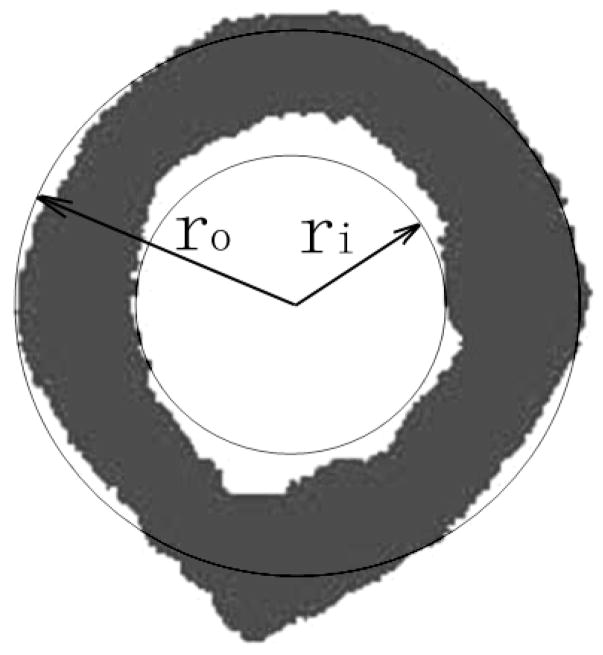

As has previously been shown, the net time delay parameters are related to the overall amount of bone in the propagation pathway [Kaufman et al. 2007; Kaufman et al. 2008a; Kaufman et al. 2008b]. Thus the cortical thickness was compared with τNetDW for the 19 radii using a linear regression. The medullar thickness was estimated using the difference τNetDW -τNetCW in a linear regression. In order to ultrasonically estimate CSA, a theoretical model relating CSA to τNetDW and τNetCW was used. In this model, inner and outer concentric circles represent approximations to the radial endosteal and periosteal surfaces, respectively (Fig. 4). Note that this construction is used only for deriving the relationship between the CSA and net time delays. The cross-sectional area of a radius is approximately equal to the area between the two circles, i.e., CSA is roughly proportional to the difference of the squares of the outer, ro and inner radii ri, viz.,

Fig. 4.

Model for estimating cross-sectional cortical area of a radius based on a nonlinear combination of τNetDW and τNetCW.

| (3) |

As already noted, τNetDW is assumed to be proportional to total cortical thickness; therefore in this model τNetDW is approximately proportional to 2·(ro−ri). It is also postulated here (and the data presented will demonstrate) that the difference (τNetDW -τNetCW) is approximately proportional to 2·ri (i.e., proportional to MT). Therefore, it follows using these two facts in conjunction with the right side of (3) that

| (4a) |

A linear multivariate regression was then used to obtain the ultrasound-based estimate, CSAUS, of CSA, i.e.,

| (4b) |

where a, b, and c are regression parameters determined by the method of least-squares.

Results

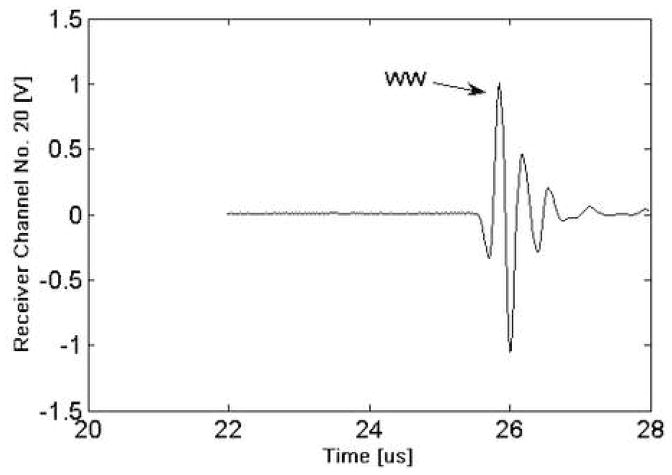

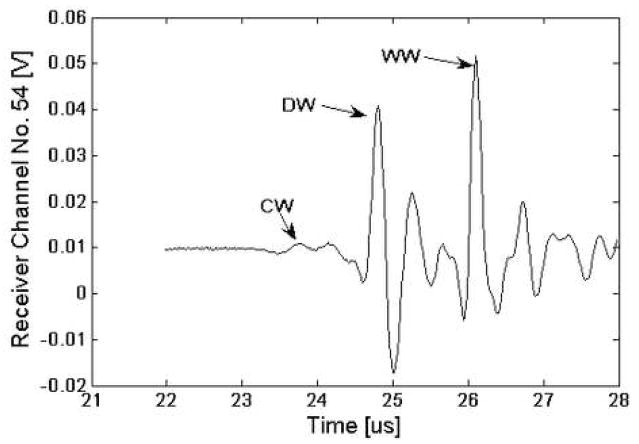

Table 1 lists the geometrical parameters (CT, MT and CSA) together with summary statistics for the nineteen radii. As may be seen, there is about a 100 percent variation in the geometrical parameters. Fig. 5 displays a signal from one channel of the receiver for the water path only (no sample). Fig. 6 presents the waveform from one receiver element located directly behind a radius (R10). As may be seen and as indicated on the figure, the three wavefronts (WW, DW and CW) are all distinctly discernible. The “water wave” appears behind the radius because the ultrasound wavefront propagates “around” the radius. In practice, the time delay of the water wave is computed based on the signal in Fig. 5, i.e., from the signal from a receiver element that is relatively distant from the radius.

Table 1.

CT, MT and CSA for the nineteen radii (sample numbers R0-R19), and summary statistics (mean, standard deviation (SD) and range).

| Sample Number | CT (mm) | MT (mm) | CSA (mm2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | 5.47 | 3.18 | 58.6 |

| R2 | 3.85 | 5.42 | 45.7 |

| R3 | 5.85 | 3.92 | 59.6 |

| R4 | 4.10 | 5.70 | 50.2 |

| R5 | 4.12 | 5.09 | 41.3 |

| R6 | 5.91 | 2.59 | 61.7 |

| R7 | 3.76 | 5.45 | 42.4 |

| R8 | 5.78 | 2.95 | 53.2 |

| R9 | 4.54 | 4.61 | 58.9 |

| R10 | 5.22 | 5.02 | 65.6 |

| R11 | 4.95 | 5.00 | 64.4 |

| R12 | 7.38 | 3.62 | 92.0 |

| R13 | 6.52 | 4.20 | 90.4 |

| R14 | 7.02 | 3.25 | 79.3 |

| R15 | 7.03 | 3.87 | 96.5 |

| R16 | 5.69 | 4.06 | 68.3 |

| R17 | 5.75 | 4.48 | 73.8 |

| R18 | 5.92 | 5.26 | 79.4 |

| R19 | 4.84 | 4.11 | 62.2 |

| Mean (SD) | 5.46 (1.09) | 4.31 (0.92) | 65.5 (16.3) |

| Range | 3.76–7.38 | 2.59–5.70 | 41.3–96.5 |

Fig. 5.

Plot of ultrasound signal for the water bath only (no sample).

Fig. 6.

Plot of the ultrasound signal for an array element directly behind radius R5. As indicated on the figure, the DW, CW and WW can be identified.

Table 2 lists the ultrasound net time delays (τNetCW and τNetDW) for the 19 radii. Again, more than a 100 percent variation in the ultrasound data is observed. Fig. 7 and Fig. 8 display the relationships between τNetDW and CT (r=0.91, p< 0.001) and τNetCW -τNetCW and MT (r=0.63, p<0.05), respectively. Fig 9 displays the relationship of the ultrasound based nonlinear estimate, CSA-US using (4b) with the actual CSA. As may be seen, the correlation between the two sets of data is high, with r = 0.95 (p<0.001). The standard errors of the estimates were 0.46 mm for CT, 0.74 mm for MT, and 5.4 mm2 for CSA.

Table 2.

Net time delays τNetCW and τNetCW for the nineteen radii (sample numbers R0–R19), and summary statistics (mean, standard deviation (SD) and range).

| Sample Number | τNetDW [μs] | τNetCW [μs] |

|---|---|---|

| R1 | 2.02 | 3.21 |

| R2 | 1.57 | 2.83 |

| R3 | 2.12 | 3.36 |

| R4 | 1.35 | 2.81 |

| R5 | 1.17 | 2.45 |

| R6 | 2.24 | 3.04 |

| R7 | 1.47 | 2.79 |

| R8 | 1.90 | 2.78 |

| R9 | 1.74 | 3.08 |

| R10 | 1.78 | 3.41 |

| R11 | 1.74 | 3.16 |

| R12 | 2.89 | 3.78 |

| R13 | 2.54 | 3.95 |

| R14 | 2.35 | 3.13 |

| R15 | 2.73 | 3.90 |

| R16 | 2.03 | 2.87 |

| R17 | 2.28 | 3.50 |

| R18 | 2.55 | 3.43 |

| R19 | 2.15 | 2.94 |

| Mean (SD) | 2.03(0.47) | 3.18 (0.41) |

| Range | 1.17–2.89 | 2.45–3.95 |

Fig. 7.

Plot of cortical thickness vs. τNetDW and linear regression fit (r = 0.91, p<0.001).

Fig. 8.

Plot of medullary thickness vs. τNetCW -τNetDW and linear regression fit (r = 0.67, p<0.05).

Fig. 9.

Plot of cross-sectional area vs. a nonlinear combination of τNetCW and τNetDW (r = 0.95, p<0.001).

Discussion and Conclusion

The in vitro data presented show that ultrasound measurements can be used to estimate cortical bone thickness, medullar thickness, and cross-sectional area of the human radius at the 1/3rd location. We believe this is the first time that a through transmission measurement at the 1/3rd location of the human radius has been used to estimate cortical thickness and cross-sectional area. Numerous studies have reported on the use of axial ultrasound measurements to estimate some aspects of bone mass and geometry [Bossy et al. 2004; Camus et al. 2000]. However, axial measurements cannot estimate CSA or MT, although recent in vitro and simulation results demonstrate the potential for estimating cortical thickness [Moilanen et al. 2007a; Moilanen et al. 2007b].

A previous clinical and simulation study reported very similar wave propagation pathways through human phalangeal bones, i.e., a direct wave and a circumferential wave as for the radii in this study [Barkmann et al. 2000]. In the study by Barkmann et al. (2000), the speed of sound (SOS) was estimated using the first arriving signal, i.e., the circumferential wave, and a correlation with cortical cross-sectional area of r=0.84 (in clinical data) was reported. A correlation of cortical thickness with ultrasound measurements was not reported, which is not surprising in view of the fact that the arrival time of the direct wave was not measured. In another study by Haiat et al. (2005), multiple propagation pathways were also reported through intact human femurs in vitro. The present study is believed to be, however, the first to examine the circumferential and direct waves in the human radius, and to use net time delay parameters to estimate cortical thickness, medullar thickness and cortical cross-sectional area all together.

We have previously reported on a computer simulation study that examined the relationship between the net time delays and cortical geometrical parameters [Kaufman et al. 2008a]. That study also found significant and strong correlations and demonstrated the ability of ultrasound measurements to estimate geometry at the 1/3rd location on the radius. The data from both studies provide a basis upon which to extend the through transmission approach to clinical measurements. In this regard, a number of issues will need to be addressed.

One such issue has to do with the potential confounding effect on the radial bone parameter estimates of variations in the velocities of ultrasound in soft tissue and cortical bone as exists both between and within individuals. A previous clinical study on the calcaneus which assumed that the velocities of ultrasound in both soft tissue and bone were each constant did yield a significant correlation between a net time delay parameter and a bone mass measurement [Kaufman et al. 2007]. In addition, the velocity of ultrasound in the bone of each radii used in the present study were presumably not the same. Thus, the use of fixed values for the two velocities in clinical application at the forearm is expected to maintain significant correlations of ultrasound parameters to bone geometry, but this will need to be demonstrated.

It is important to note the expected range of values for the estimated parameters that would be observed clinically. A reasonable assessment can be made by comparing the relative change in BMD at the 1/3rd location measured that has been observed using DXA; a percent change of about 100% between a young normal and osteoporotic person (T-score = −2.5) is typical [Bonnick 2004]. Since the data variations reported in this study for the geometrical parameters are also of the order of 100%, and since the standard errors of the estimates are relatively small with respect to these variations, it is reasonable to expect that the technique may be clinically useful. This will need to be clinically validated in the context of expected changes in the geometrical parameters relative to precision of the estimates; this topic is examined in the the context of “least significant change” in Bonnick (2004). A related topic that has not been addressed in this study is the issue of reproducibility. This will need to be done in the specific context of repositioning of the forearm and repeat measurements. Although we have not reported the data here, the reproducibility of the net time delay parameters without repositioning is significantly less than one percent.

Clinical studies will also be important to determine the relationship of the ultrasound net time delay parameters at the radius to overall osteoporotic fracture risk. In terms of fractures, those at the hip are associated with the highest degree of morbidity and mortality [Miller 1978; Anonymous 2001] and are therefore the most clinically relevant. However, measurement of bone mass at the distal radius is also related to fracture risk at the hip. For example, it has been shown that low BMD at the forearm is associated with more than a two-fold risk of fracture at any site, including the hip [Miller et al. 2002]. Moreover, it has been reported that changes in BMD at the hip and distal radius were mostly in agreement, whereas changes in total body and spine were generally incongruous [Warming et al. 2002]. Since cortical thickness and cross-sectional area are related to bone strength and fracture risk, the ultrasound technique presented here may prove useful for estimating hip fracture risk [Sornay-Rendu 2005; Boutroy et al. 2007; Boutroy et al. 2008]. Another key point to note is that a distal radius fracture is very often the first sign of osteoporosis, and indicates that the radius can be a useful site for screening [Hegeman et al. 2004].

Although bone mass per se is the most important factor in determining bone strength, geometry has also been shown to play a role. Besides the direct roles that cortical thickness and cross-sectional area may have in determining bone strength (as noted in the previous paragraph), it has also been demonstrated that low width of tubular bones is associated with increased risk of fragility fractures [Szulc et al. 2006]. It is also generally accepted that reductions in bone strength as caused by endosteal resorption can be mitigated by periosteal apposition, even in the face of reduced total bone mass [Seeman, 2002]. Therefore, it will be interesting to see if the medullar size estimate based on the difference of the two net time delays, in conjunction with cortical thickness and cross-sectional area, may play a role in identifying those individuals most at risk of fracture.

In conclusion, this in vitro study has demonstrated the ability of ultrasound to non-invasively estimate the cortical thickness, medullar thickness and cross-sectional area at the 1/3rd location on the human radius. Clinical studies using a desktop ultrasound scanner for ultrasound assessment at the forearm are presently being planned.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by Grant Number R44AR054307 from the National Institute of Arthritis And Musculoskeletal And Skin Diseases. The support of the Carroll and Milton Petrie Foundation is also gratefully acknowledged. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute Of Arthritis And Musculoskeletal And Skin Diseases or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anonymous. Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. JAMA. 2001;285:785–95. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.6.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkmann R, Lusse S, Stampa B, Sakata S, Heller M, Gluer C-C. Assessment of the geometry of human finger phalanges using quantitative ultrasound in vivo. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11:745–755. doi: 10.1007/s001980070053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake GM, Fogelman I. Review - DXA scanning and its interpretation in osteoporosis. Hosp Med. 2003;64:521–5. doi: 10.12968/hosp.2003.64.9.2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnick SL. Bone densitometry in clinical practice: Application and interpretation. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bossy E, Talmant M, Laugier P. Three-dimensional simulations of ultrasonic axial transmission velocity measurement on cortical bone models. J Acoust Soc Am. 2004;115(5):2314–2324. doi: 10.1121/1.1689960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutroy S, Bouxsein ML, Munoz F, Delmas PD. In vivo assessment of trabecular bone microarchitecture by high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(12):6508–15. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutroy S, Van Rietbergen B, Sornay-Rendu E, Munoz F, Bouxsein ML, Delmas PD. Finite element analysis based on in vivo HR-pQCT images of the distal radius is associated with wrist fracture in postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23(3):392–9. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.071108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camus E, Talmant M, Berger G, Laugier P. Analysis of the axial transmission technique for the assessment of skeletal status. J Acoust Soc Am. 2000;108(6):3058–3065. doi: 10.1121/1.1290245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings SR, Black DM, Nevitt MC, Browner W, Cauley J, Ensrud K, Genant HK, Palermo L, Scott J, Vogt TM. Bone density at various sites for prediction of hip fractures. The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Lancet. 1993;341(8837):72–5. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92555-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glüer CC. Quantitative Ultrasound--it is time to focus research efforts. Bone. 2007;40(1):9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haïat G, Padilla F, Peyrin F, Laugier P. Variation of ultrasonic parameters with microstructure and material properties of trabecular bone: a 3D model simulation. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22(5):665–74. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haïat G, Padilla F, Barkmann R, Kolta S, Latremouille C, Gluer C-C, Laugier P. In vitro speed of sound measurement at intact human femur specimens. Ultrasound in Med & Biol. 2005;31(7):987–996. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegeman JH, Oskam J, van der Palen J, Ten Duis HJ, Vierhout PA. The distal radius in elderly women and the bone mineral density of the lumbar spine and hip. J Hand Surg [Br] 2004;29(5):473–476. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsb.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnell O, Kanis JA, Oden A, Johansson H, De Laet C, Delmas P, Eisman JA, Fujiwara S, Kroger H, Mellstrom D, Meunier PJ, Melton LJ, 3rd, O’Neill T, Pols H, Reeve J, Silman A, Tenenhouse A. Predictive value of BMD for hip and other fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:1185–1194. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanis J. Diagnosis of osteoporosis and assessment of fracture risk. The Lancet. 2002;359:1929–1936. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08761-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman JJ, Siffert RS. Non-invasive assessment of bone integrity. In: Cowin S, editor. Bone mechanics handbook. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2001. pp. 34.1–34.25. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman JJ, Luo GM, Siffert RS. A Portable Real-Time Bone Densitometer. Ultrasound in Med & Biol. 2007 Sep;33(9):1445–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman JJ, Luo GM, Siffert RS. Ultrasound Simulation in Bone. IEEE Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics and Frequency Control. 2008a doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2008.784. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman JJ, Luo GM, Blazy B, Siffert RS. Quantitative ultrasound assessment of tubes and rods: comparison of empirical and computational results. In: Akiyama I, editor. Acoustical Imaging. Vol. 29. Springer; New York, NY: 2008b. (in press) [Google Scholar]

- LeFloch V, McMahon DJ, Luo GM, Cohen A, Kaufman JJ, Shane E, Siffert RS. Ultrasound simulation in the distal radius using clinical high-resolution peripheral-CT images. Ultrasound in Med & Biol. 2008;34 doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melton LJ., III . Epidemiology of fractures. In: Riggs BL, Melton LJ III, editors. Osteoporosis: etiology, diagnosis, and management. New York, NY: Raven Press; 1988. pp. 133–154. [Google Scholar]

- Miller CW. Survival and ambulation following hip fracture. J Bone Joint Surg. 1978;60A:930–934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller PD, Siris ES, Barrett-Connor EB, Faulkner KG, Wehren LE, Abbott TA, Chen YT, Berger ML, Santora AC, Sherwood LM. Prediction of fracture risk in postmenopausal white women with peripheral bone densitometry: evidence from the National Osteoporosis Risk Assessment. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:2222–2230. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.12.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moilanen P, Talmant M, Bousson V, Nicholson PHF, Cheng S, Timonen J, Laugier P. Ultrasonically determined thickness of long cortical bones: Two-dimensional simulations of in vitro experiments. J Acoust Soc Am. 2007a;122(3):1818–1826. doi: 10.1121/1.2756758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moilanen P, Nicholson PHF, Kilappa V, Cheng S, Timonen J. Assessment of the cortical bone thickness using ultrasonic guided waves: modeling and in vitro study. Ultrasound in Med & Biol. 2007b;33(2):254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njeh CF, Hans D, Fuerst T, Gluer C-C, Genant H. Quantitative ultrasound: Assessment of osteoporosis and bone status. London, England: Martin Dunitz Ltd; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Seeman E. Pathogenesis of bone fragility in women and men. The Lancet. 2002;359(9320):1841–1850. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08706-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siffert RS, Kaufman JJ. Ultrasonic Bone Assessment: ‘The Time Has Come’ (Editorial) Bone. 2007;40(1):5–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siris ES, Brenneman SK, Barrett-Connor E, Miller PD, Sajjan S, Berger ML, Chen YT. The effect of age and bone mineral density on the absolute, excess, and relative risk of fracture in postmenopausal women aged 50–99: results from the National Osteoporosis Risk Assessment (NORA) Osteoporos Int. 2006;17(4):565–74. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-0027-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sornay-Rendu E, Boutroy S, Munoz F, Delmas PD. Alterations of cortical and trabecular architecture are associated with fractures in postmenopausal women, partially independent of decreased BMD measured by DXA: the OFELY study. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22(3):425–33. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.061206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szulc P, Munoz F, Duboeuf F, Marchand F, Delmas P. Low width of tubular bones is associated with increased risk of fragility fracture in elderly men—the MINOS study. Bone. 2006;38:595–602. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warming L, Hassager C, Christiansen C. Changes in bone mineral density with age in men and women: a longitudinal study. Osteoporos Int. 2002;13:105–112. doi: 10.1007/s001980200001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]