Abstract

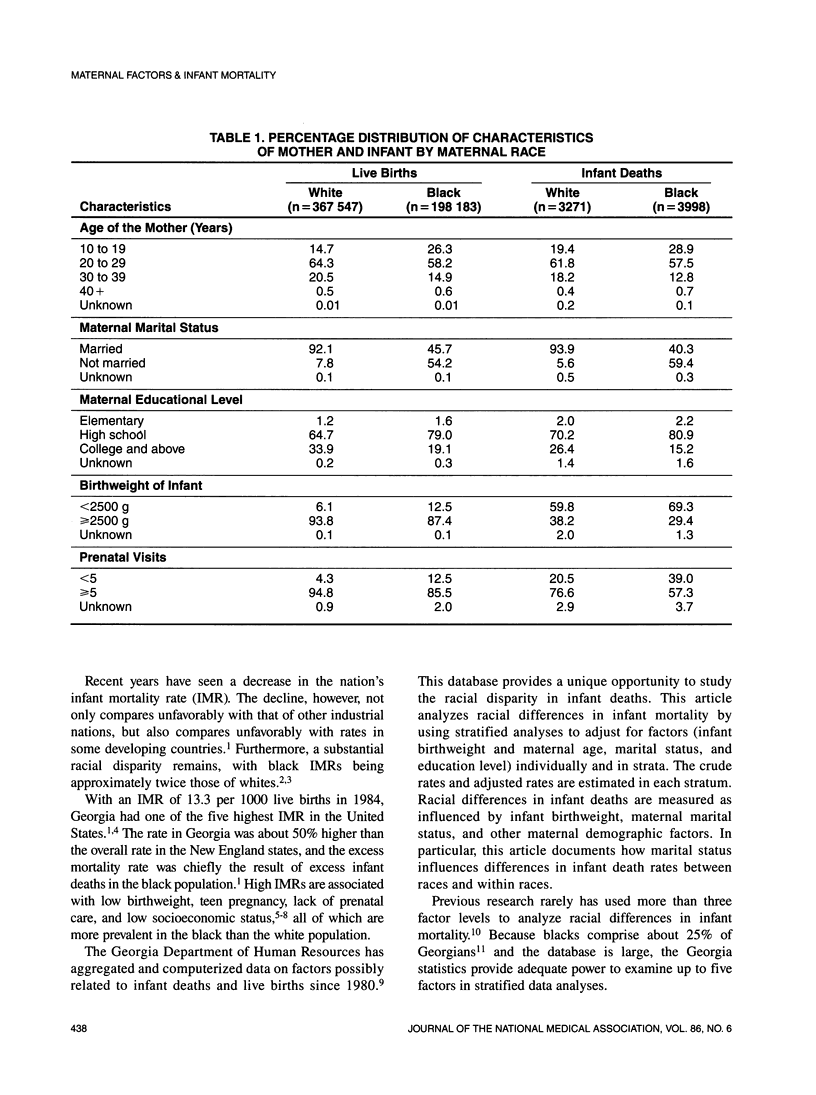

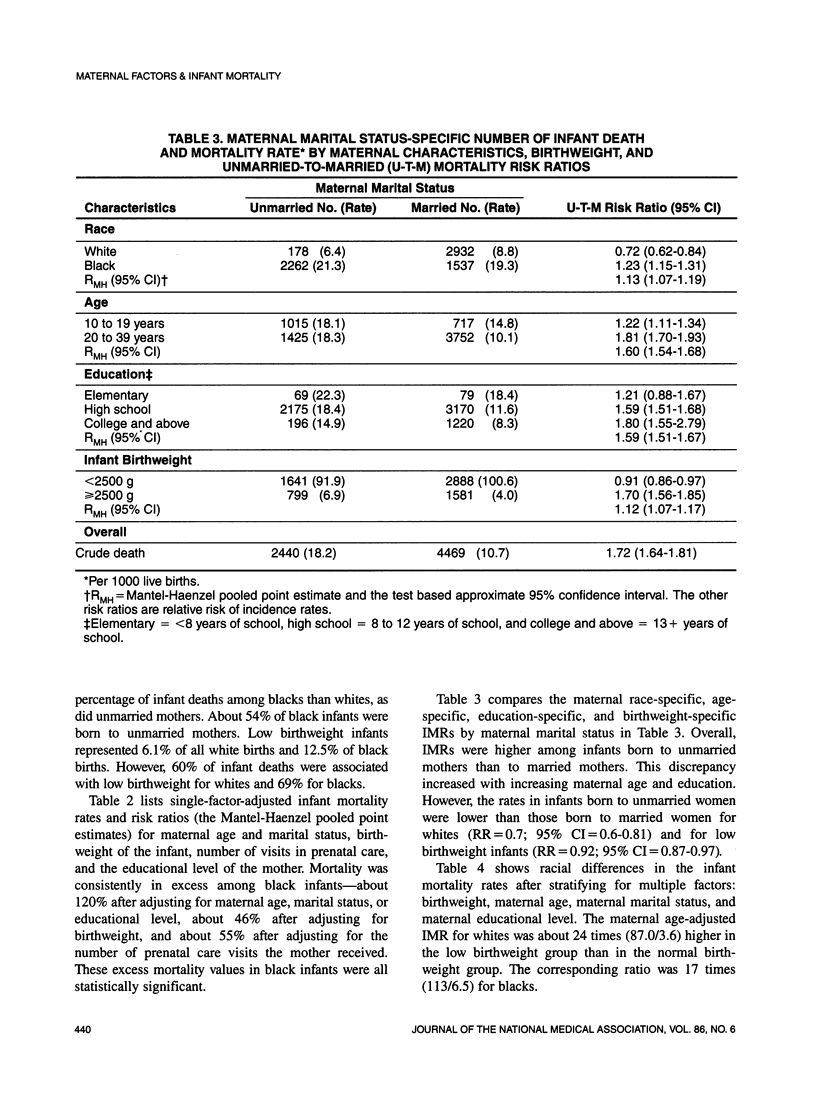

Black infant mortality rates (IMRs) are approximately twice those of whites in Georgia and nationwide. This study evaluates maternal factors, particularly marital status, that influence racial differences in infant mortality. Population-based data on 565,730 live births and 7269 infant deaths in Georgia from 1980 to 1985 were examined. The IMR ratio for unmarried compared to married mothers was calculated and adjusted singly for maternal education, age and race, and infant birthweight. In addition, racial differences in IMR were estimated using stratified analysis on the basis of four factors: infant birthweight, maternal age, marital status, and education. When only normal birthweight infants were considered, the IMR, adjusted for maternal education level, was highest for infants born to unmarried black teens (9.5/1000 live births), followed by that for infants born to married black teens (9.1), unmarried black adults (7.5), married black adults (4.8), married white teens (4.4), married white adults (3.4), unmarried white adults (2.4), and unmarried white teens (1.3). When only low birthweight infants were considered, the highest IMR per 1000 was found in infants born to married black adults (119), followed by unmarried black adults (103), married black teens (99.9), unmarried black teens (92.5), married white adults (92.1), married white teens (79.0), unmarried white adults (38.0), and unmarried white teens (26.3). These differences led to a black-to-white IMR risk ratio from 1.3 for low birthweight infants born to unmarried teen or adult mothers to 3.7 for normal birthweight infants born to unmarried teen mothers.(ABSTRACT TRUNCATED AT 250 WORDS)

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Binkin N. J., Rust K. R., Williams R. L. Racial differences in neonatal mortality. What causes of death explain the gap? Am J Dis Child. 1988 Apr;142(4):434–440. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1988.02150040088026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control (CDC) National birthweight-specific infant mortality surveillance: preliminary analysis--United States, 1980. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1986 May 2;35(17):269–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer J. C. Social factors and infant mortality: identifying high-risk groups and proximate causes. Demography. 1987 Aug;24(3):299–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce T. The demand for health inputs and their impact on the black neonatal mortality rate in the U.S. Soc Sci Med. 1987;24(11):911–918. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(87)90284-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman J. C. State trends in infant mortality, 1968-83. Am J Public Health. 1986 Jun;76(6):681–688. doi: 10.2105/ajph.76.6.681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks J. S., Buehler J. W., Strauss L. T., Hogue C. J., Smith J. C. Variation in state-specific infant mortality risks. Public Health Rep. 1987 Mar-Apr;102(2):146–151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paneth N., Wallenstein S., Kiely J. L., Susser M. Social class indicators and mortality in low birth weight infants. Am J Epidemiol. 1982 Aug;116(2):364–375. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegman M. E. Annual summary of vital statistics--1984. Pediatrics. 1985 Dec;76(6):861–871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]