Abstract

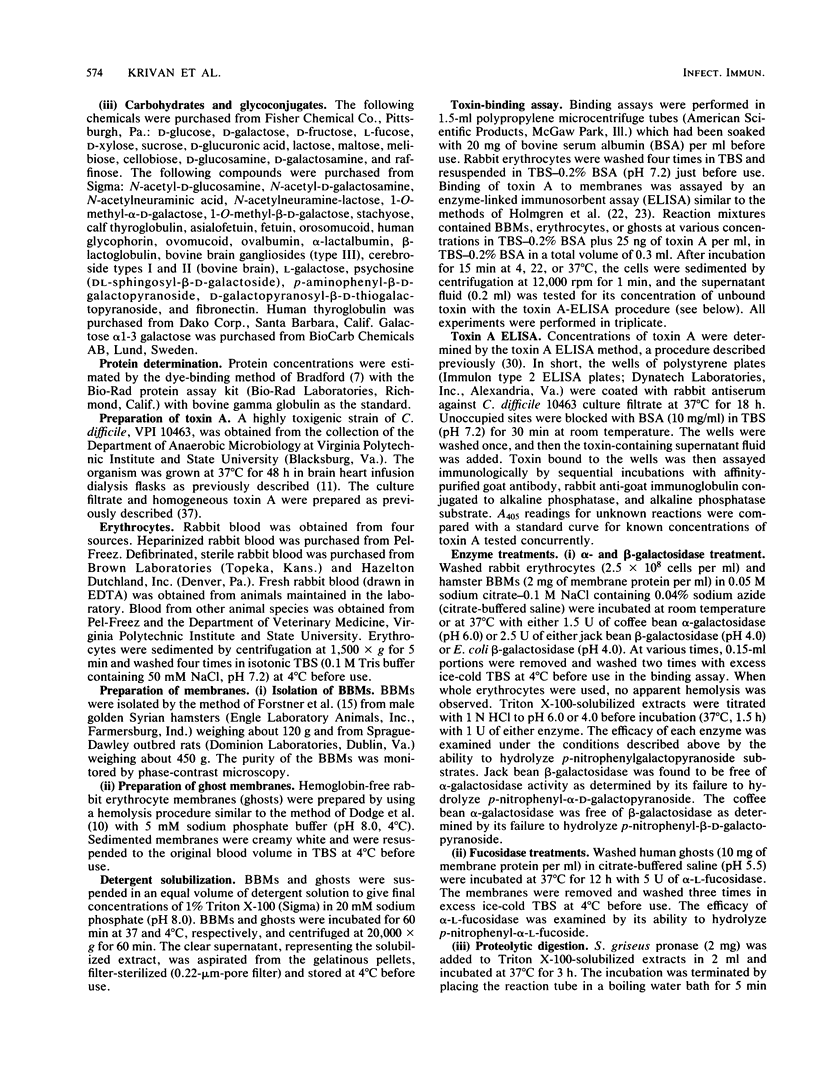

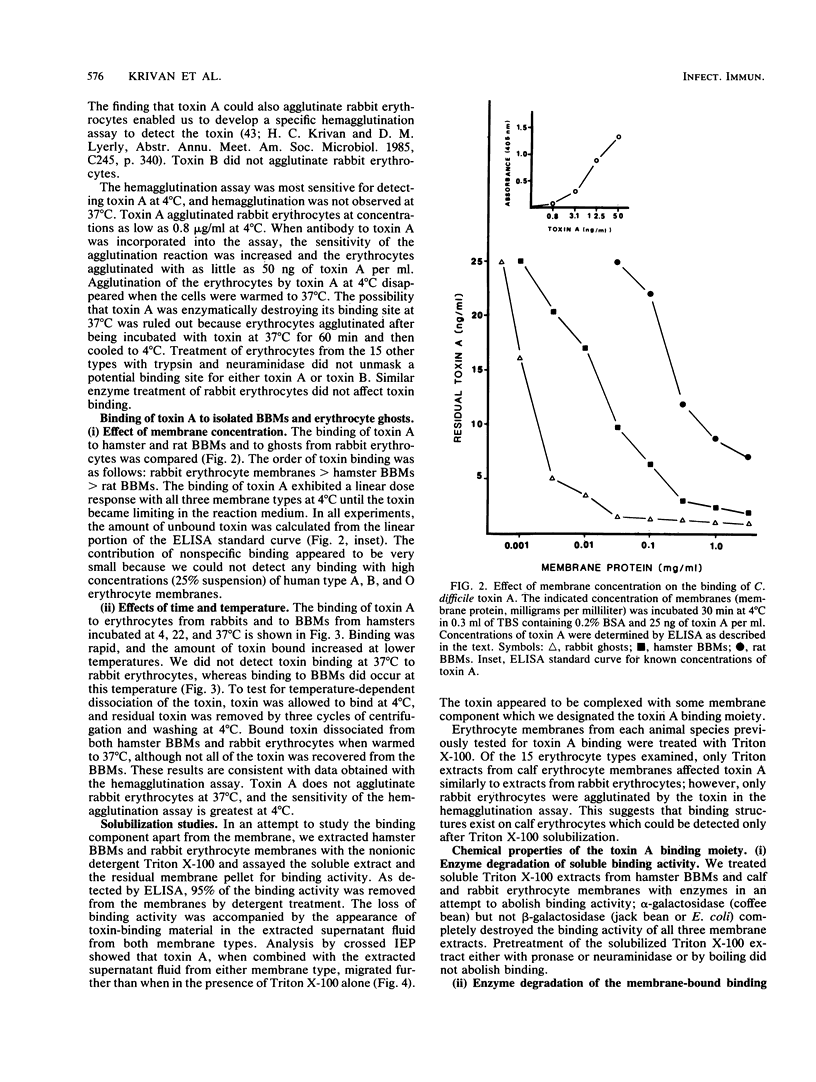

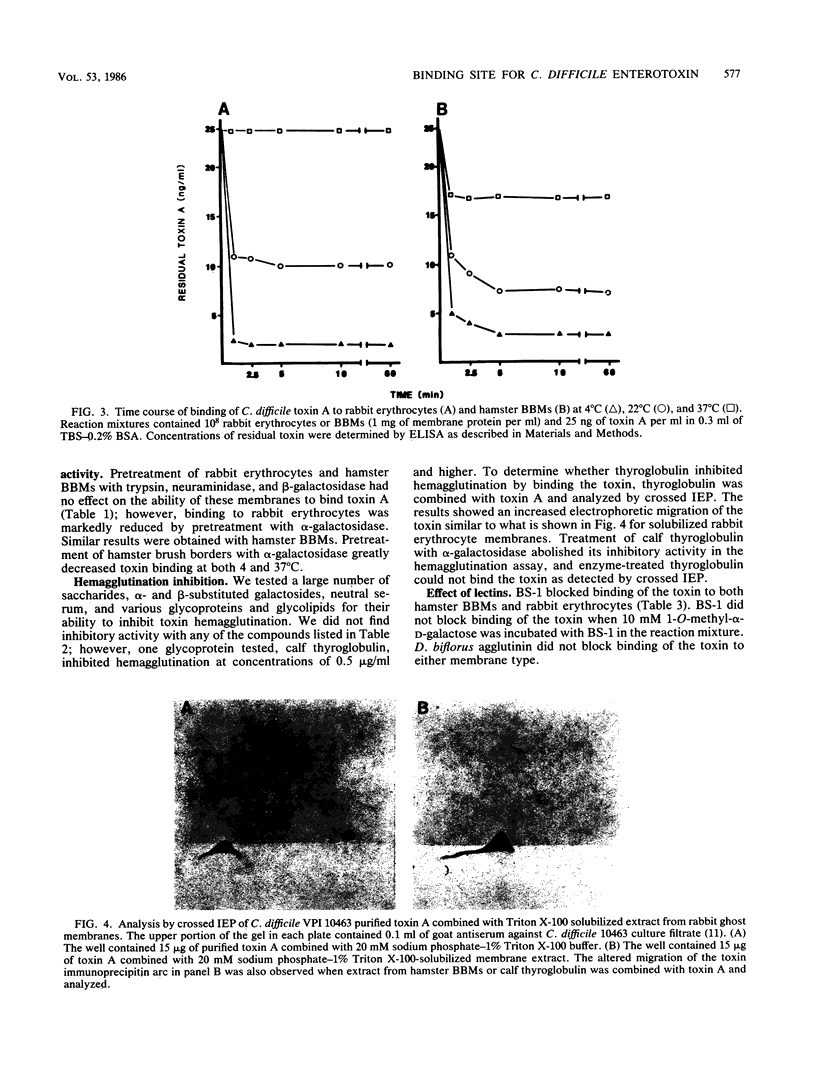

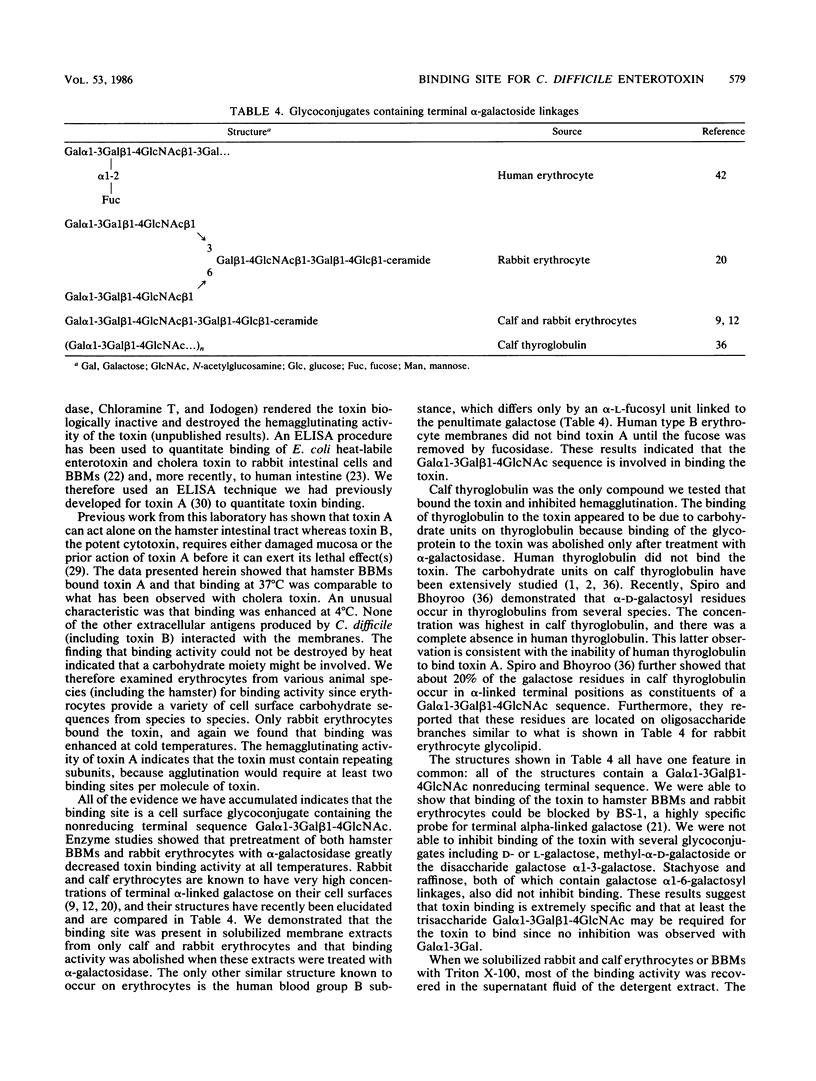

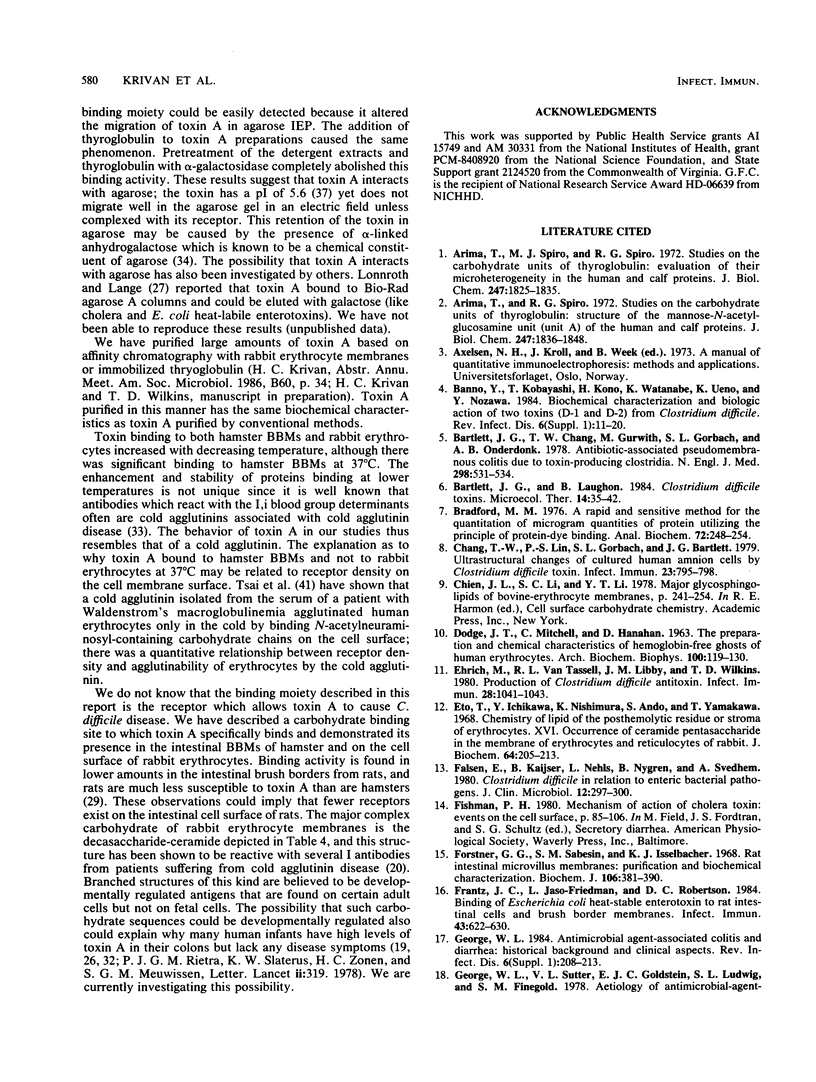

This study was undertaken to determine whether a binding site for Clostridium difficile enterotoxin (toxin A) exists in the brush border membranes (BBMs) of the hamster, an animal known to be extremely sensitive to the action of the toxin. Toxin A was the only antigen adsorbed by the BBMs from the culture filtrate of C. difficile. The finding that binding activity could not be destroyed by heat indicated that a carbohydrate moiety might be involved. We therefore examined erythrocytes from various animal species for binding activity since erythrocytes provide a variety of carbohydrate sequences on their cell surfaces. Only rabbit erythrocytes bound the toxin, and the cells agglutinated. A binding assay based on an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay method for quantifying C. difficile toxin A was used to compare binding of the toxin to hamster BBMs, rabbit erythrocytes, and BBMs from rats, which are less susceptible to the action of C. difficile toxin A than hamsters. Results of this comparison indicated the following order of toxin-binding frequency: rabbit erythrocytes greater than hamster BBMs greater than rat BBMs. Binding of toxin A to hamster BBMs at 37 degrees C was comparable to what has been observed with cholera toxin, but binding was enhanced at 4 degrees C. A similar binding phenomenon was observed with rabbit erythrocytes. Examination of the cell surfaces of hamster BBMs and rabbit erythrocytes with lectins and specific glycosidases revealed a high concentration of terminal alpha-linked galactose. Treatment of both membrane types with alpha-galactosidase destroyed the binding activity. The glycoprotein, calf thyroglobulin, also bound the toxin and inhibited toxin binding to cells. Toxin A did not bind to human erythrocytes from blood group A, B, or O donors. However, after fucosidase treatment of human erythrocytes, only blood group B erythrocytes, which possess the blood group B structure Gal alpha 1-3[Fuc alpha 1-2]Gal beta 1-4GlcNAc-R, bound the toxin. This indicated that toxin A was likely binding to Gal alpha 1-3Gal beta 1-4GlcNAc, a carbohydrate sequence also found on calf thyroglobulin and rabbit erythrocytes. All of the results indicate that hamster BBMs contain a carbohydrate-binding site for toxin A that has at least a Gal alpha 1-3Gal beta 1-4GlcNAc nonreducing terminal sequence.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Arima T., Spiro M. J., Spiro R. G. Studies on the carbohydrate units of thyroglobulin. Evaluation of their microheterogeneity in the human and calf proteins. J Biol Chem. 1972 Mar 25;247(6):1825–1835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arima T., Spiro R. G. Studies on the carbohydrate units of thyroglobulin. Structure of the mannose-N-acetylglucosamine unit (unit A) of the human and calf proteins. J Biol Chem. 1972 Mar 25;247(6):1836–1848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett J. G., Chang T. W., Gurwith M., Gorbach S. L., Onderdonk A. B. Antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis due to toxin-producing clostridia. N Engl J Med. 1978 Mar 9;298(10):531–534. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197803092981003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976 May 7;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang T. W., Lin P. S., Gorbach S. L., Bartlett J. G. Ultrastructural changes of cultured human amnion cells by Clostridiu difficile toxin. Infect Immun. 1979 Mar;23(3):795–798. doi: 10.1128/iai.23.3.795-798.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DODGE J. T., MITCHELL C., HANAHAN D. J. The preparation and chemical characteristics of hemoglobin-free ghosts of human erythrocytes. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1963 Jan;100:119–130. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(63)90042-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrich M., Van Tassell R. L., Libby J. M., Wilkins T. D. Production of Clostridium difficile antitoxin. Infect Immun. 1980 Jun;28(3):1041–1043. doi: 10.1128/iai.28.3.1041-1043.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eto T., Ichikawa Y., Nishimura K., Ando S., Yamakawa T. Chemistry of lipid of the posthemyolytic residue or stroma of erythrocytes. XVI. Occurrence of ceramide pentasaccharide in the membrane of erythrocytes and reticulocytes of rabbit. J Biochem. 1968 Aug;64(2):205–213. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a128881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falsen E., Kaijser B., Nehls L., Nygren B., Svedhem A. Clostridium difficile in relation to enteric bacterial pathogens. J Clin Microbiol. 1980 Sep;12(3):297–300. doi: 10.1128/jcm.12.3.297-300.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forstner G. G., Sabesin S. M., Isselbacher K. J. Rat intestinal microvillus membranes. Purification and biochemical characterization. Biochem J. 1968 Jan;106(2):381–390. doi: 10.1042/bj1060381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frantz J. C., Jaso-Friedman L., Robertson D. C. Binding of Escherichia coli heat-stable enterotoxin to rat intestinal cells and brush border membranes. Infect Immun. 1984 Feb;43(2):622–630. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.2.622-630.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George W. L., Sutter V. L., Goldstein E. J., Ludwig S. L., Finegold S. M. Aetiology of antimicrobial-agent-associated colitis. Lancet. 1978 Apr 15;1(8068):802–803. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)93001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurwith M. J., Langston C., Citron D. M. Toxin-producing bacteria in infants. Lack of an association with sudden infant death syndrome. Am J Dis Child. 1981 Dec;135(12):1104–1106. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1981.02130360012006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanfland P., Egge H., Dabrowski U., Kuhn S., Roelcke D., Dabrowski J. Isolation and characterization of an I-active ceramide decasaccharide from rabbit erythrocyte membranes. Biochemistry. 1981 Sep 1;20(18):5310–5319. doi: 10.1021/bi00521a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes C. E., Goldstein I. J. An alpha-D-galactosyl-binding lectin from Bandeiraea simplicifolia seeds. Isolation by affinity chromatography and characterization. J Biol Chem. 1974 Mar 25;249(6):1904–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren J., Fredman P., Lindblad M., Svennerholm A. M., Svennerholm L. Rabbit intestinal glycoprotein receptor for Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin lacking affinity for cholera toxin. Infect Immun. 1982 Nov;38(2):424–433. doi: 10.1128/iai.38.2.424-433.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren J., Lindblad M., Fredman P., Svennerholm L., Myrvold H. Comparison of receptors for cholera and Escherichia coli enterotoxins in human intestine. Gastroenterology. 1985 Jul;89(1):27–35. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(85)90741-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson H. E., Price A. B. Pseudomembranous colitis: Presence of clostridial toxin. Lancet. 1977 Dec 24;2(8052-8053):1312–1314. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)90363-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby J. M., Donta S. T., Wilkins T. D. Clostridium difficile toxin A in infants. J Infect Dis. 1983 Sep;148(3):606–606. doi: 10.1093/infdis/148.3.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsky B. A., Gates J., Tenover F. C., Plorde J. J. Factors affecting the clinical value of microscopy for acid-fast bacilli. Rev Infect Dis. 1984 Mar-Apr;6(2):214–222. doi: 10.1093/clinids/6.2.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyerly D. M., Lockwood D. E., Richardson S. H., Wilkins T. D. Biological activities of toxins A and B of Clostridium difficile. Infect Immun. 1982 Mar;35(3):1147–1150. doi: 10.1128/iai.35.3.1147-1150.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyerly D. M., Saum K. E., MacDonald D. K., Wilkins T. D. Effects of Clostridium difficile toxins given intragastrically to animals. Infect Immun. 1985 Feb;47(2):349–352. doi: 10.1128/iai.47.2.349-352.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyerly D. M., Sullivan N. M., Wilkins T. D. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for Clostridium difficile toxin A. J Clin Microbiol. 1983 Jan;17(1):72–78. doi: 10.1128/jcm.17.1.72-78.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lönnroth I., Lange S. Toxin A of Clostridium difficile: production, purification and effect in mouse intestine. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand B. 1983 Dec;91(6):395–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1983.tb00066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonel J. L. Binding of Clostridium perfringens [125I]enterotoxin to rabbit intestinal cells. Biochemistry. 1980 Oct 14;19(21):4801–4807. doi: 10.1021/bi00562a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash J. Q., Chattopadhyay B., Honeycombe J., Tabaqchali S. Clostridium difficile and cytotoxin in routine faecal specimens. J Clin Pathol. 1982 May;35(5):561–565. doi: 10.1136/jcp.35.5.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roelcke D. Cold agglutination. Antibodies and antigens. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1974 Jan;2(2):266–280. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(74)90044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiro R. G., Bhoyroo V. D. Occurrence of alpha-D-galactosyl residues in the thyroglobulins from several species. Localization in the saccharide chains of the complex carbohydrate units. J Biol Chem. 1984 Aug 10;259(15):9858–9866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan N. M., Pellett S., Wilkins T. D. Purification and characterization of toxins A and B of Clostridium difficile. Infect Immun. 1982 Mar;35(3):1032–1040. doi: 10.1128/iai.35.3.1032-1040.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor N. S., Thorne G. M., Bartlett J. G. Comparison of two toxins produced by Clostridium difficile. Infect Immun. 1981 Dec;34(3):1036–1043. doi: 10.1128/iai.34.3.1036-1043.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thelestam M., Brönnegård M. Interaction of cytopathogenic toxin from Clostridium difficile with cells in tissue culture. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl. 1980;(Suppl 22):16–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai C. M., Zopf D. A., Ginsburg V. The molecular basis for cold agglutination: effect of receptor density upon thermal amplitude of a cold agglutinin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1978 Feb 28;80(4):905–910. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(78)91330-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins W. M. Blood-group substances. Science. 1966 Apr 8;152(3719):172–181. doi: 10.1126/science.152.3719.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins T., Krivan H., Stiles B., Carman R., Lyerly D. Clostridial toxins active locally in the gastrointestinal tract. Ciba Found Symp. 1985;112:230–241. doi: 10.1002/9780470720936.ch13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]