Abstract

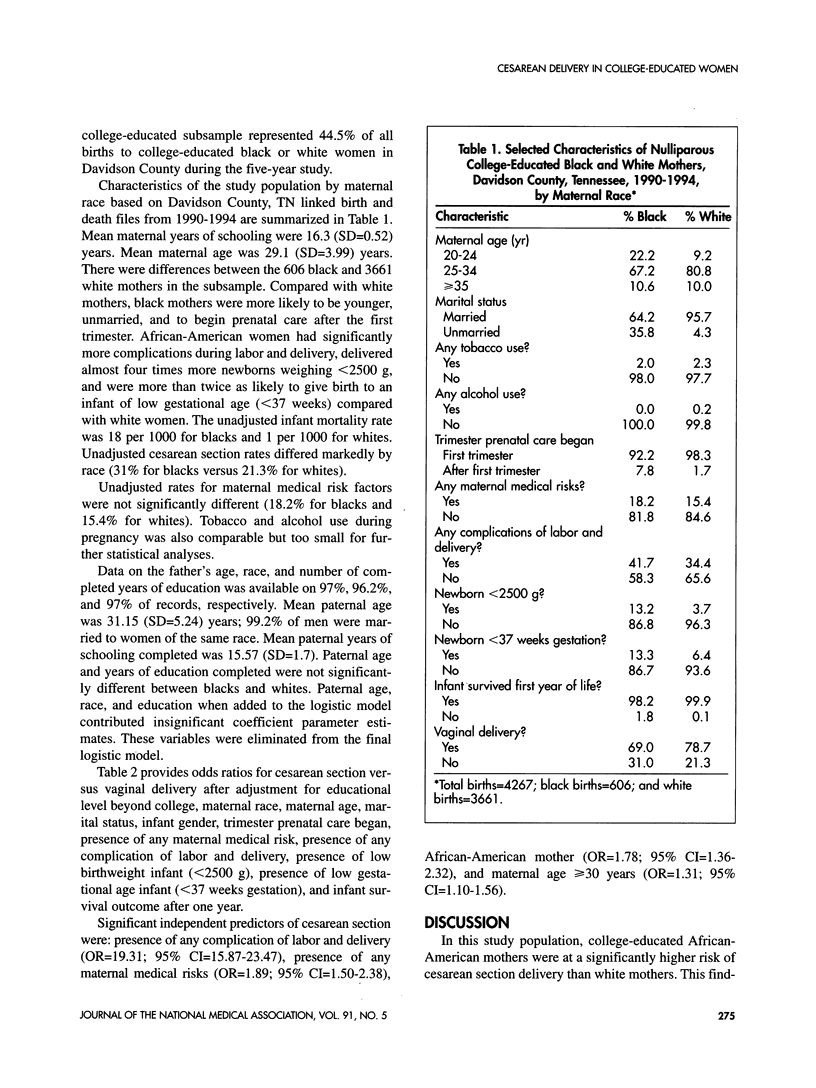

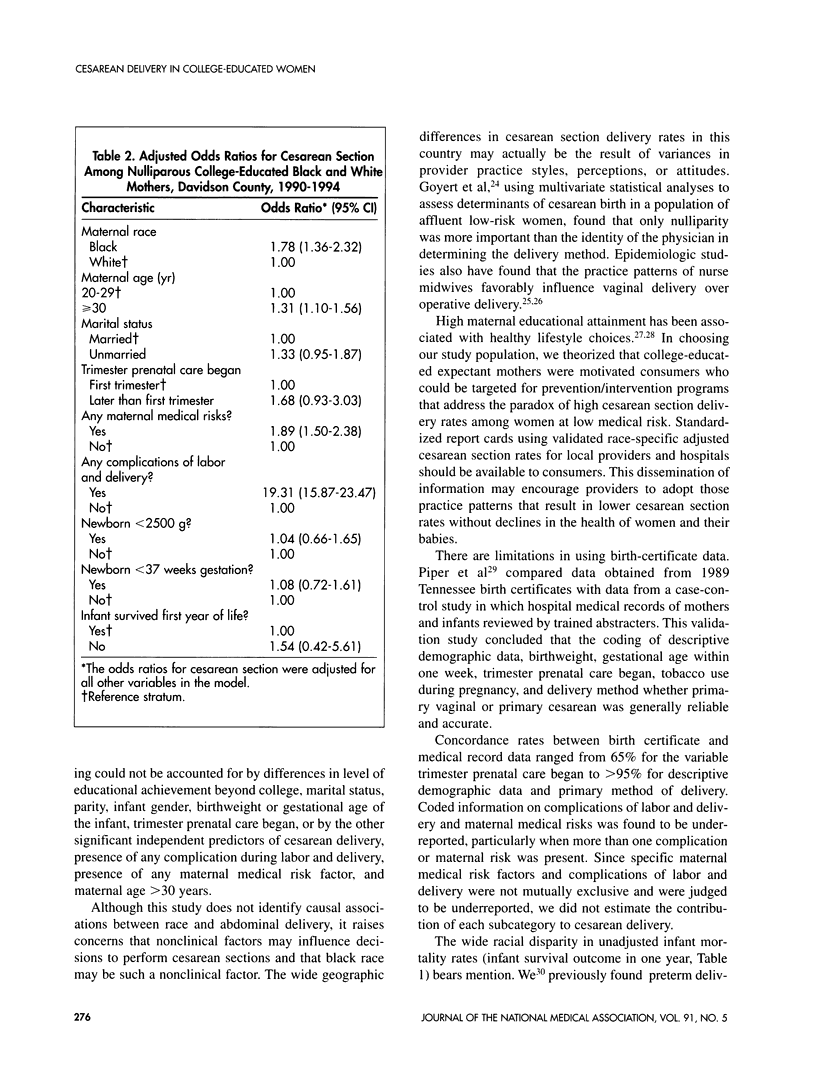

Cesarean section delivery increases the cost, morbidity, and mortality of childbirth. Cesarean section rates vary nationwide with the highest rates occurring in the southern United States. The Department of Health and Human Services has published year 2000 objectives that include a 15% reduction in the cesarean section rate. This study identified factors contributing to cesarean section delivery among a cohort of college-educated black and white women in Davidson County, TN. Logistic regression models were applied to Linked Infant Birth and Death certificate data from 1990-1994. Data on singleton first births for 606 black women and 3661 white women completing 16 years of education were analyzed. College-educated African Americans were at a significantly higher risk of cesarean section delivery than whites. This difference could not be accounted for by controlling for all other variables. The geographic differences in cesarean section rates in this country may be the result of varying in provider practice styles, perceptions, or attitudes. Improving the health of women and children will require establishing a system of maternity care that is comprehensive, case-managed, culturally appropriate, and available to all women.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bashore R. A., Phillips W. H., Jr, Brinkman C. R., 3rd A comparison of the morbidity of midforceps and cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990 Jun;162(6):1428–1435. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)90902-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braveman P., Egerter S., Edmonston F., Verdon M. Racial/ethnic differences in the likelihood of cesarean delivery, California. Am J Public Health. 1995 May;85(5):625–630. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.5.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan H., Hawrylyshyn P., Hogg-Johnson S., Inwood S., Finley A., D'Costa M., Chipman M. Perinatal factors associated with the respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990 Feb;162(2):476–481. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)90415-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler J., Abrams B., Parker J., Roberts J. M., Laros R. K., Jr Supportive nurse-midwife care is associated with a reduced incidence of cesarean section. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993 May;168(5):1407–1413. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(11)90773-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Rates of cesarean delivery--United States, 1993. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1995 Apr 21;44(15):303–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke S. C., Taffel S. M. State variation in rates of cesarean and VBAC delivery: 1989 and 1993. Stat Bull Metrop Insur Co. 1996 Jan-Mar;77(1):28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis L. G., Riedmann G. L., Sapiro M., Minogue J. P., Kazer R. R. Cesarean section rates in low-risk private patients managed by certified nurse-midwives and obstetricians. J Nurse Midwifery. 1994 Mar-Apr;39(2):91–97. doi: 10.1016/0091-2182(94)90016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon D., Milberg J., Daling J., Hickok D. Advanced maternal age as a risk factor for cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 1991 Apr;77(4):493–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould J. B., Davey B., Stafford R. S. Socioeconomic differences in rates of cesarean section. N Engl J Med. 1989 Jul 27;321(4):233–239. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198907273210406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyert G. L., Bottoms S. F., Treadwell M. C., Nehra P. C. The physician factor in cesarean birth rates. N Engl J Med. 1989 Mar 16;320(11):706–709. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198903163201106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin D. E., Savitz D. A., Bowes W. A., Jr, St André K. A. Race, age, and cesarean delivery in a military population. Obstet Gynecol. 1996 Oct;88(4 Pt 1):530–533. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(96)00263-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King D. E., Lahiri K. Socioeconomic factors and the odds of vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. JAMA. 1994 Aug 17;272(7):524–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J. M., Jr Maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality in cesarean section. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1988 Dec;15(4):629–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mushinski M. Average charges for uncomplicated cesarean and vaginal deliveries, United States, 1993. Stat Bull Metrop Insur Co. 1994 Oct-Dec;75(4):27–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peipert J. F., Bracken M. B. Maternal age: an independent risk factor for cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 1993 Feb;81(2):200–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper J. M., Mitchel E. F., Jr, Snowden M., Hall C., Adams M., Taylor P. Validation of 1989 Tennessee birth certificates using maternal and newborn hospital records. Am J Epidemiol. 1993 Apr 1;137(7):758–768. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Placek P. J., Taffel S., Moien M. Cesarean section delivery rates: United States, 1981. Am J Public Health. 1983 Aug;73(8):861–862. doi: 10.2105/ajph.73.8.861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Wright A. O., Wrona R. M., Flanagan T. M. Predictors of infant mortality among college-educated black and white women, Davidson County, Tennessee, 1990-1994. J Natl Med Assoc. 1998 Aug;90(8):477–483. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford R. S. Cesarean section use and source of payment: an analysis of California hospital discharge abstracts. Am J Public Health. 1990 Mar;80(3):313–315. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.3.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford R. S., Sullivan S. D., Gardner L. B. Trends in cesarean section use in California, 1983 to 1990. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993 Apr;168(4):1297–1302. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90384-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford R. S. The impact of nonclinical factors on repeat cesarean section. JAMA. 1991 Jan 2;265(1):59–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taffel S. M. Cesarean delivery in the United States, 1990. Vital Health Stat 21. 1994 May;(51):1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thom M. H., Chan K. K., Studd J. W. Outcome of normal and dysfunctional labor in different racial groups. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1979 Oct 15;135(4):495–498. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(79)90438-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turcot L., Marcoux S., Fraser W. D. Multivariate analysis of risk factors for operative delivery in nulliparous women. Canadian Early Amniotomy Study Group. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997 Feb;176(2):395–402. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70505-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams R. L., Chen P. M. Controlling the rise in cesarean section rates by the dissemination of information from vital records. Am J Public Health. 1983 Aug;73(8):863–867. doi: 10.2105/ajph.73.8.863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahniser S. C., Kendrick J. S., Franks A. L., Saftlas A. F. Trends in obstetric operative procedures, 1980 to 1987. Am J Public Health. 1992 Oct;82(10):1340–1344. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.10.1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]