Abstract

Ultra smooth nanostructured diamond (USND) coatings were deposited by microwave plasma chemical vapor deposition (MPCVD) technique using He/H2/CH4/N2 gas mixture. The RMS surface roughness as low as 4 nm (2 micron square area) and grain size of 5–6 nm diamond coatings were achieved on medical grade titanium alloy. Previously it was demonstrated that the C2 species in the plasma is responsible for the production of nanocrystalline diamond coatings in the Ar/H2/CH4 gas mixture. In this work we have found that CN species is responsible for the production of USND coatings in He/H2/CH4/N2 plasma. It was found that diamond coatings deposited with higher CN species concentration (normalized by Balmer Hα line) in the plasma produced smoother and highly nanostructured diamond coatings. The correlation between CN/Hα ratios with the coating roughness and grain size were also confirmed with different set of gas flows/plasma parameters. It is suggested that the presence of CN species could be responsible for producing nanocrystallinity in the growth of USND coatings using He/H2/CH4/N2 gas mixture. The RMS roughness of 4 nm and grain size of 5–6 nm were calculated from the deposited diamond coatings using the gas mixture which produced the highest CN/Hα species in the plasma. Wear tests were performed on the OrthoPOD®, a six station pin-on-disk apparatus with ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene (UHMWPE) pins articulating on USND disks and CoCrMo alloy disk. Wear of the UHMWPE was found to be lower for the polyethylene on USND than that of polyethylene on CoCrMo alloy.

Keywords: Nanostructure, diamond films, plasma CVD, wear

Introduction

In the United States, an estimated 11 million people have received at least one medical implant device. The number of total hip and knee replacements performed each year in the U.S.A is 198,000 and 245,000 respectively [1]. Revision surgeries account for 17 percent of all hip replacement and eight percent of all knee replacement surgeries, for a combined total of nearly 54,000 revision surgeries each year. Despite improvements in the surgical technique and in the designs of prostheses, revision rates do not seem to be declining over time. Wear of articulating surfaces is a major problem in orthopedic and dental devices, including the temporo-mandibular joint (TMJ), which resides in very close proximity to the eye, the ear, various nerves, and the brain [2,3]. In some cases, TMJ implant devices are needed and their success is greatly influenced by the degree of wear at articulating surfaces. Wear debris generated from articulating surface is responsible for osteolysis which is the major problem for implant failure. In recent year, nanostructured diamond has been identified as a potentially useful material for wear resistance coating applications. Therefore, a major goal is to develop ultra smooth and wear resistant coatings on the articulation surfaces in order to reduce the friction and wear in mating total joint replacement components.

One disadvantage of the orthopedic and dental implant replacements is their lifetime and durability. Wear and stress from the contact eventually leads to failure. Especially with the hip replacements, the polyethylene is greatly disturbed by contact with the metal head. After time osteolysis, the loss of bone due to the wear of the inserted joint, occurs [1]. One solution for this problem is to coat the articulating surfaces with wear resistant materials with high hardness and low coefficient of friction. The smoother the contact, the less wear that will occur. This is expected to greatly enhance the lifetime and durability of the joint replacements. Therefore, our focus for the past several years is to optimize the diamond coating in hopes to produce ultra smooth nanostructured diamond coatings for joint replacements.

Though many research groups have been producing nanocrystalline diamond (NCD) films, there have been different views as to what is responsible for growing such thin films. The traditional growth route was based on high H2 content (99%) with very low CH4 content (1%) [4]. However, this leads to microcrystalline diamond films with high surface roughness [5]. In an attempt to grow smooth diamond films, a new plasma chemistry was introduced by Gruen and co-workers. This is either a CH4/Ar mixture or a C60/Ar mixture, both with very little hydrogen content [4,6]. Strong C2 Swan band optical emission was observed using optical emission spectrometry (OES) and from this it was proposed that C2 may be the growth species for NCD. Ab initio calculations supported the hypothesis that C2 could insert directly into the C–H bonds which terminate the growing diamond surface. Similar results were obtained using Ar/H2/CH4 gas compositions in microwave plasma. These high noble gas content mixtures provided new routes for diamond growth. Researchers have found that high noble gas content with some carbon precursor allows for secondary nucleation to occur [4]. This leads to nanocrystalline diamond with crystallite sizes 3–15 nm [4]. However, later research was aimed at determining whether C2 dimer was responsible for nanocrystalline diamond. Rabeau et al [7] grew nanocrystalline diamond films in Ar/H2/CH4 and He/H2/CH4 plasmas. They detected via OES strong C2 emission in the Ar plasma, yet in the He plasma C2 could not be detected. However, their conclusion was based on the fact that for both noble gas containing plasmas the growth rates were similar. This along with the fact that nanocrystalline diamond film was grown in the presence of the He plasma, which contained undetectable C2 levels, led them to the conclusion that C2 dimer is not the key growth species [7]. Also, there was no correlation between the amount of C2 and the growth rate in the Ar plasma [7]. Since it was accepted that the addition of noble gas to the plasma greatly enhances the quality by reducing the roughness and grain size of the NCD, research was directed at optimizing the other parameters involving diamond growth.

Nanostructured diamond films have also been a research topic of interest at University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) for the past several years. Catledge and Vohra [8] studied the effect of N2 on the way to produce nanostructured diamond films. They found that N2 addition produced smooth nanocrystalline diamond coatings with root-mean-squared (rms) surface roughness of 18 nm. They concluded that the addition of N2 results in a smoother film [8]. Later research led to the addition of He to the plasma gas mixture H2/CH4/N2. Konovalov et al [9] attained nanostructured diamond with RMS surface roughness of 9–10 nm with average grain size of 5–6 nm. These results were obtained under the optimal condition when He occupied 71% of the gas mixtures. They also found a difference in C2 intensity when using He instead of Ar.

The work by Chowdhury et al [10] further reduced the roughness and grain size. They produced ultra nanostructured diamond coating which they named as Ultra Smooth Nanostructured Diamond (USND) coating with roughness as low as 5 nm and grain size less than 6 nm. They varied the N2/CH4 from 0.05 to 0.6 in H2/CH4/N2/He and concluded that the optimal value with low roughness and grain size was achieved at the N2/CH4 of 0.4 [10]. Their results also imply that nanocrystalline diamond can be grown without high C2 content [9, 10]. In this article we demonstrate that the CN species in the H2/CH4/N2/He plasma might be responsible for producing nanocrystallinity in the USND coatings. Characterization of the deposited coating were done by using Raman spectroscopy, glancing angle XRD, atomic force microcopy (AFM), optical emission spectroscopy (OES), nanoindentation technique etc. We also evaluated the wear performance of the USND coated titanium alloy against standard polyethylene that is the common material for orthopedic and dental implants.

Experimental details

USND coatings were deposited by microwave plasma chemical vapor deposition (MPCVD) technique using He/H2/CH4/N2 gas mixture. Medical grade titanium alloy (Ti–6Al–4V) disks with 25.4 mm diameter and 3.4 mm thickness were used as substrate materials. They were polished to a root-mean-square (RMS) roughness of 3–4 nm using polishing technique described elsewhere [10]. The polished disks were cleaned by ultrasonic agitation in a 1 micron diamond powder/water solution after a series of detergent solution, methanol, acetone, and finally deionized water. Cleaned substrates were placed in a Wavemat MPCVD reactor, equipped with a 6 kW, 2.4 GHz microwave generator. Chamber pressure was 65 Torr and the substrate temperature, as measured by “Mikron M77LS Infraducer” two-color IR pyrometer, was kept in the range 690–720 °C by adjusting microwave power in the range 0.93–1.1 kW. This two color pyrometer provided accurate measurement of the substrate temperature without requiring correction of the emissivity of the surface during growth. Flow rates of H2, CH4, N2, and He varied throughout the experiments. Optical emission spectroscopy (OES) was performed to qualitatively determine the activated species present in the plasma. All the measurements were taken with 3000 points in the range of 350–700 nm wavelength and integration time of 250 ms.

The crystallinity of the diamond films was analyzed by micro-Raman spectroscopy. The Raman spectra were taken using the 514.5 nm line of an argon-ion laser focused onto the film at a laser power of 100 mW. The Raman scattered signal was analyzed by a high resolution spectrometer (1 cm−1 resolution) coupled to a CCD system. XRD patterns on the diamond sample were examined using glancing angle XRD (X’pert MPD, Philips, Eindhoven, The Netherlands). XRD was performed using a glancing angle of 3-degree. Spectra were taken from 30 to 95 (2-theta) at a scan speed of 0.012° min−1 and a step size of 0.005° as well as from 40 to 47 (2- theta) in order to clearly document the intensity and Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM) of the diamond (111) diffraction peak.

Structure and surface morphology of the diamond surfaces was imaged by, a TopoMetrix Explorer® AFM. The images were collected in non-contact imaging mode. The images obtained were processed by TopoMetrix SPM Lab NT Version 5.0 software supplied with the microscope. The processing consists of a second order leveling of the surface and a left shading of the image. Roughness was measured from a 2 μm2 scan area consistently for all samples. Surfaces of the diamond film were also imaged by FEI Nova NanoSEM™.

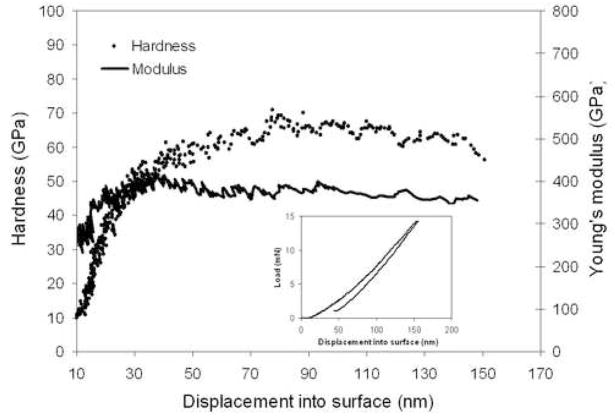

The hardness and Young’s modulus of the diamond films was measured using a Nanoindenter XP (MTS Systems, Oak Ridge TN) system with a continuous stiffness (CSM) attachment which provided continuous hardness/modulus measurements with increasing depth into the film [11,12]. The system was calibrated by using silica samples for a range of operating conditions. Silica modulus and hardness were calculated as 70 GPa and 9.1 GPa and 71 and 9.5, respectively, before and after indentation on diamond samples. A Berkovich diamond indenter with total included angle of 142.3° was used and the maximum indentation depth of 150 nm was maintained for all the measurements. The data was processed using proprietary software to produce load-displacement curves and the mechanical properties were calculated using the Oliver and Pharr method [13].

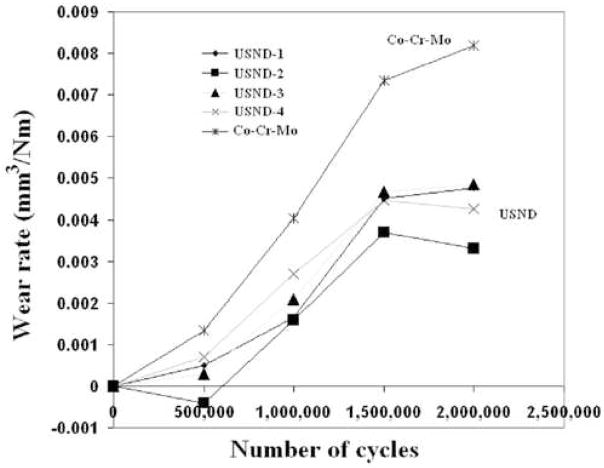

Three different sets of samples were subjected to wear testing. 1. USND coated Ti–6Al–4V disks against polyethylene and compared with medical grade cobalt chromium alloy (CoCrMo). 2. USND coated Ti–6Al–4V disks against USND coated pins 3. Multilayer diamond (defined as a four layers structure composed first layer of nano-structured diamond using H2/CH4/N2 plasma then second layer of micro-structured diamond using H2/CH4 plasma, third layer of nano-structured diamond and final layer of USND coatings) coated Ti–6Al–4V disks against multilayer diamond coated Ti–6Al–4V pins. The wear test was performed using the OrthoPOD® (AMTI, Watertown, MA) following the guidelines set by the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM Standard F 732) [14]. For the test lubricant we used bovine calf serum that was mixed with 80 mL of 250 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) that binds the calcium, and mixed with 2g of sodium azide, an antibacterial agent that stops the formation of calcium phosphate on the components or on its surfaces [15,16]. The temperature of the serum was held constant at 37°C. Since, the OrthoPOD® is a six station pin-on-disk apparatus; we used one station for a soak control pin that had no contact to a disk. It was used for any fluid absorption and in the calculation of mass loss for each pin, which accounted for any mass change of the soak control pin during the wear test [15]. The CoCrMo disk was polished to a mirror like finish with no visible scratches on the surface by following the same procedure as for Ti–6Al–4V. We then placed the disks into the stages where stations 1–4 were the USND coated Ti–6Al–4V disks (USND 1 to USND 4), station 5 was the CoCrMo disk, and station 6 was used for the soak control pin. Before starting the wear test the contacting surfaces of each UHMWPE pin were shaved (approximately 180 to 270 μm) using a Microtome (Polycut S Reíchert-Jung BE16023). This gave it a smooth finish, which was free of any machining marks. Before starting the wear tests the pins had been soaked for at least two weeks in distilled water [15]. Prior to starting the wear test, the pins were cleaned according to ASTM Standard F 732 in 1% LiquiNox® solution that was sonically agitated for 15 minutes, then rinsed with distilled water and sonically agitated again in distilled water for five minutes. The pins were dried with a lint free tissue and then placed in ethyl alcohol for about three minutes then dried under a dust-free vacuum for 30 minutes. After each cleaning the pins were weighed on a Mettler Toledo AG245 microbalance with five separate measurements to 0.00001g, and then averaged. All of the pins were weighed prior to testing and after every 500,000 cycles. We ran the wear test for two million cycles at 500,000 cycles per interval where this amount of cycles showed wear of the UHMWPE pins. At the end of every 125,000 cycles, the OrthoPOD® was programmed to record the loads and coefficient of friction of every pin. In finding the wear factor (k) we used Achard’s Law, which can be calculated by finding the volumetric wear rate or the volume loss (Q) and the product of the average vertical force (F) with the total sliding distance (d), and then dividing the two to give the equation where k = Q/(F*d). This wear test ran under applied forces that ranged from 15 to 130 N. The UHMWPE pins were articulating on the disks in a square shaped pattern, where the surface of the polyethylene will change based on the multidirectional motion of the pin. This prevents the polymer chain in the polyethylene to align itself and present a practical simulation [16, 17]. The wear test was also performed for diamond coated Ti–6Al–4V disks and diamond coated Ti–6Al–4V pin couples. The tests were done for each pin and disk for 1000 cycles at 5 Newtons.

Results and discussion

In our previous work it has been reported that with the introduction of helium gas in H2/CH4/N2 plasma, the transformation from microcrystalline to nanocrystalline occurred and roughness decreased dramatically [9]. The roughness decreased from 19–20 nm to 9–10 nm with the introduction of helium up to 71%. We again found that the roughness goes down to 5 nm and grain size of 6 nm using H2/CH4/N2/He plasma where N2/CH4 = 0.4 [10]. In this work we tried to correlate the roughness and grain size with the amount of CN species present in the plasma.

It was found that with the increase of He addition in the H2/CH4/N2/He plasma the CN/Hα species increased. In order to investigate the amount of CN species in the plasma different gases in several proportions have been introduced in the CVD reactor and OES spectra was obtained during the experiment. Since multiple gases were introduced into the CVD reactor, the plasma chemistry can become quite complicated. CN is one fragment in the plasma that has a strong detection peak in OES. Different flow rates (sccm) of H2, CH4, N2, and He were studied and CN species normalized by Balmer Hα line were monitored. Several diamond coatings were deposited using different amount of CN concentration in plasma (from high to low). After that correlations were made with film quality like roughness, hardness and nanocrystallinity with the relative amount of CN species in the plasma. Among all the gas combinations H2/CH4/N2/He: 100/36/21.6/250 sccm produced CN/Hα of 7.6, H2/CH4/N2/He: 100/36/14.4/250 sccm produced 6.4 where as H2/CH4/N2/He: 200/36/14.4/300 sccm produced 2.8 and H2/CH4/N2/He: 500/88/8.8/0 sccm of 0.87. The optical emission spectra of the He/H2/CH4/N2 microwave plasmas with CN/Hα of 6.4 and 2.8 are shown in figure 1. Interestingly it was found that there was a very small amount of C2 emission in the plasma compare to CN and other species. Therefore, C2 dimer is not contributing for the growth of nano-structured diamond coatings. On the other hand there was a strong peak from CN emission in the OES spectra and it changed with the small change of plasma chemistry. Also, an experiment was performed to determine if changing the absolute flow rates of the gases while keeping the ratios the same would affect the results. It was concluded that the flow rate does not affect results as long as the ratio is unchanged. Further analysis via AFM, Raman spectroscopy, thin-film X-ray diffraction (XRD) and nanoindentation were used to characterize the film grown with this experimentally optimized plasma chemistry containing low and high values of CN/Hα.

Figure 1.

The optical emission spectra of the He/H2/CH4/N2 microwave plasmas with different ratios of CN/Hα in the plasma.

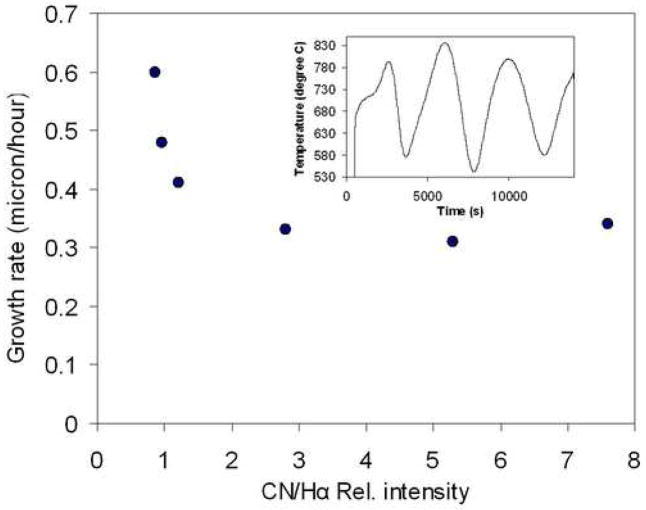

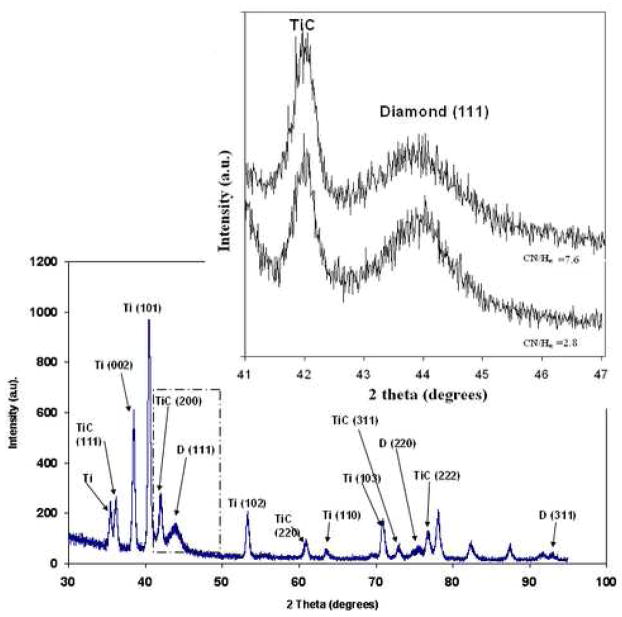

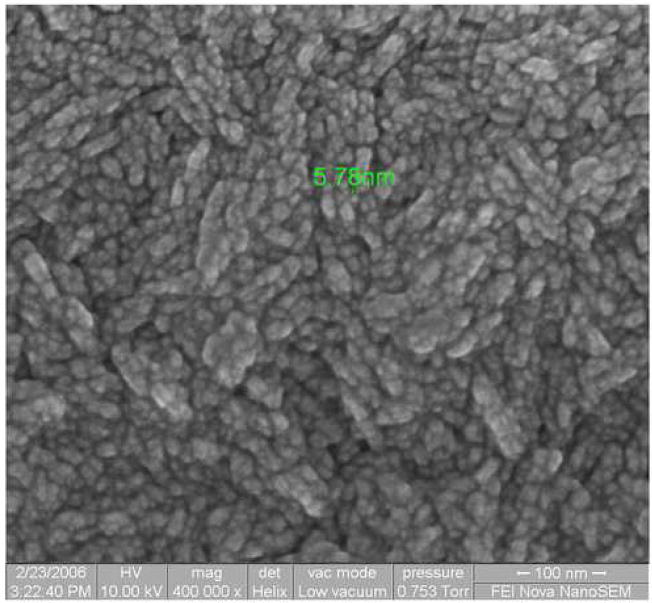

Figure 2 shows the diamond growth rate in relation to CN/Hα ratios. The growth rate dropped as the CN/Hα ratios increased and it stayed constant with the increase of the CN concentrating in the plasma. Higher levels of CN radicals reduce the CH3 concentration and thus reduce the growth rate [18]. Figure 3 shows the glancing angle XRD patterns for the nanostructured diamond films grown on Ti–6Al–4V alloy using the He/CH4/H2/N2 feed gas mixture where CN/Hα in the plasma is 7.6. Characteristic of these patterns are the cubic diamond (111) and (220) reflections as well as several peaks attributed to interfacial titanium carbide phases. The diamond peaks shown in the insert were significantly broadened as compared to those obtained from the conventional CVD process. The diamond coating deposited with high CN/Hα (7.6) produced broader peak than the diamond coating deposited with CN/Hα value of 2.8. The results demonstrated that the plasma containing more species of CN produced broader diamond (111) peak due to the production of more nano-structured diamond. The average grain size as calculated from the diamond (111) peak width using the Scherrer formula was between 4–6 nm. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) image at 400,000X on the surface of diamond sample grown in He/H2/CH4/N2 plasma containing CN/Hα ratio of 5.1 is shown in figure 4. The grain size is as low as 5.7 nm and confirms the diamond nanostructure.

Figure 2.

Growth rate of diamond films at different CN/Hα ratios. In the inset, the optical interference pattern collected from interferometer is shown for film deposited at CN/Hα of 7.6.

Figure 3.

The glancing angle XRD patterns for the nanostructured diamond films grown on Ti–6Al–4V alloy using the He/CH4/H2/N2 feed gas mixture where CN/Hα in the plasma is 7.6. The insert show the close-up view of TiC and diamond (111) peaks showing the change due to the change of CN/Hα.

Figure 4.

Electron Microscope (SEM) image at 400,000X on the surface of diamond sample grown in He/H2/CH4/N2 plasma containing CN/Hα ratio of 5.1.

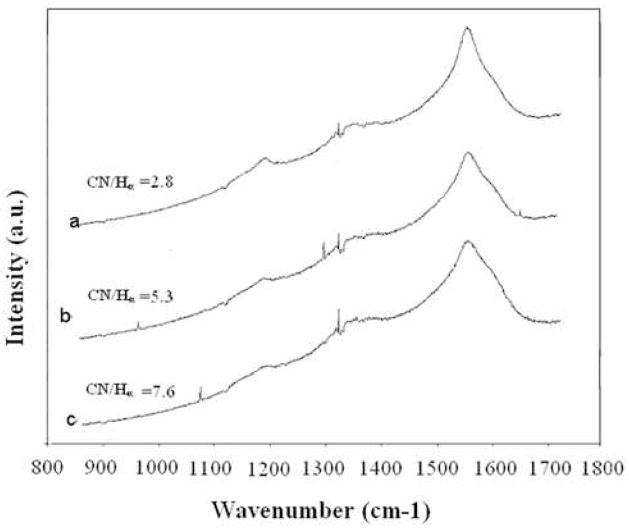

The micro-Raman spectra for the nanostructured diamond coatings deposited in the plasma containing different CN species concentration are shown in figure 5. The Raman spectra show the significantly broadened diamond peak at around 1332 cm−1 due to the sp3 bonded carbon [19]. Again slightly broaden peak at around 1450–1600 cm−1 region is assigned to graphite (sp2 bonded carbon, G band). The Raman spectra have another peak at 1150 cm−1 in addition to the main diamond and graphite bands. It is suggested that this band is due to the nanocrystalline nature of the diamond films [20]. The films produced consist of diamond nanocrystallites imbedded in amorphous carbon matrix with a relatively small amount of graphitic carbon. The Raman spectra collected from different diamond coatings show significant difference in their 1550 cm−1 and 1150 cm−1 bands. These bands appear to sharpen as the CN/Hα ratio decreases.

Figure 5.

Raman spectra of nanostructured diamond coatings deposited in different CN/Hα in the plasma.

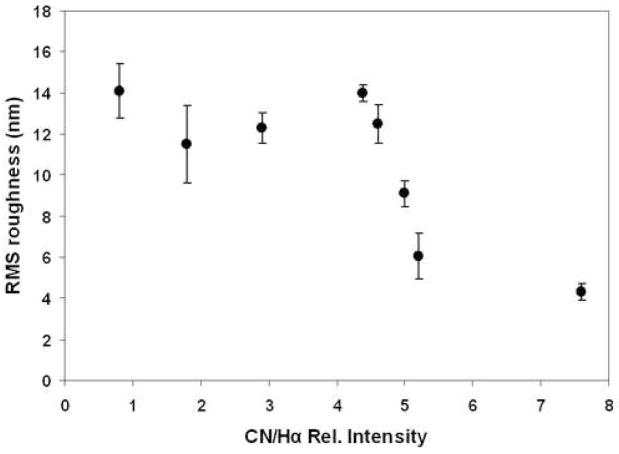

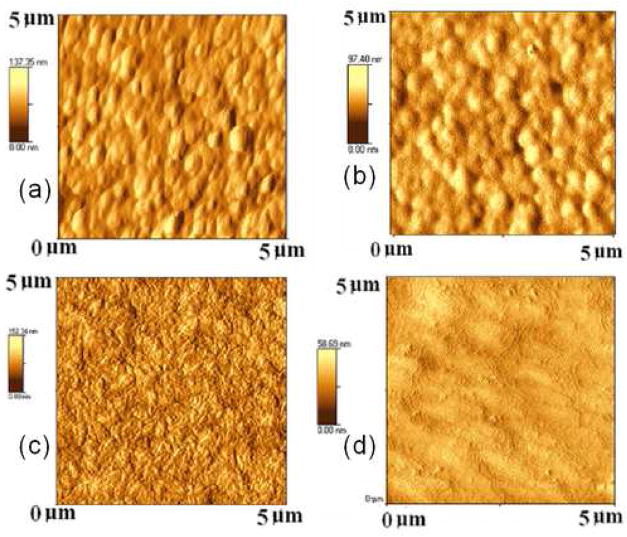

AFM images revealed that with the increase of CN species concentration in the plasma it was possible to produce smoother diamond coatings. Figure 6 shows the relation between the CN species concentration (normalized by Balmer Hα line) with the roughness of the diamond surfaces. As the CN species concentration increased the roughness was decreased. RMS roughness value as low as 4.3 nm (2 μm2 scan area) was achieved using H2/CH4/N2/He of 100/36/21.6/250 sccm containing CN/Hα of 7.6 in the plasma. AFM images shown in figure 7 clearly demonstrate the morphological change due to the change of CN species concentration in the plasma.

Figure 6.

A plot of the surface roughness measured in 2×2 μm area of different as-grown diamond films with different CN/Hα in the plasma.

Figure 7.

AFM images of the as-grown diamond films prepared from microwave plasma showing the morphological change due to change in different CN/Hα in the plasma (a) CN/Hα of 0.87 (b) CN/Hα of 1.8 (c) CN/Hα of 2.8 (d) CN/Hα of 7.6.

The hardness and Young’s modulus of USND coating deposited with CN/Hα value of 5.1 is 65 ± 5 GPa and 400 ± 24 GPa. The hardness and nanoindentation modulus variation over depth is shown in the figure 8 along with typical load-displacement curve. Generally hardness has been regarded as a primary material property, which defines wear resistance. There is a strong evidence to suggest that the elastic modulus can also have an important influence on wear behavior, in particular, the elastic strain to failure, which is related to the ratio of hardness (H) and elastic modulus (E). It has been shown by a number of authors [21] that the elastic strain to failure could be a more suitable parameter for predicting wear resistance than hardness alone. It is also significant that the ratio between H and E described in terms of ‘plasticity index’ or ‘elastic strain to failure’ are widely quoted as a valuable parameter in determining the limit of elastic behaviour in a surface contact, which is clearly important for the avoidance of wear [22, 17]. We calculated the H/E value as 0.16 for USND coatings where the typical value for biomedical grade polyethylene is 0.07, Ti-6Al-4V is 0.03 and CoCrMo is 0.04.

Figure 8.

Nanoindentation hardness and modulus vs depth for ultra smooth nanostructured diamond coating at CN/Hα = 5.3 in He/H2/CH4/N2 plasma. Nanoindentation load-displacement curve for same sample is shown in the insert.

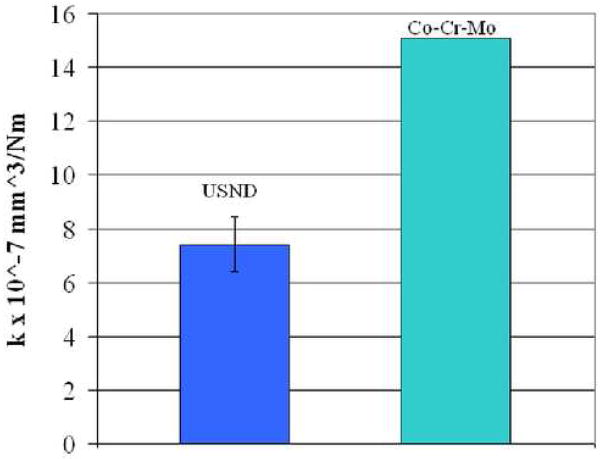

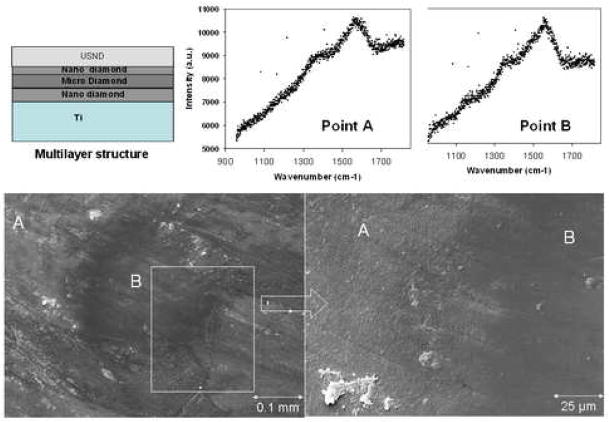

Two types of wear studies were performed. First we studied diamond coated Ti-6Al-4V surfaces against polyethylene and then diamond coated pins against diamond coated disks. All four of the USND coated metal surfaces against polyethylene pins exhibited lower wear than CoCrMo on polyethylene. The wear of the UHMWPE pins were graphed on up to 2 million cycles in figure 9. The average value of k for USND was 7.41 mm3/Nm and the value for CoCrMo was more than twice the USND, at 15.1 mm3/Nm, shown in figure 10. In the diamond against diamond wear, virtually no wear was seen in the pin and disk combinations coated with multilayered coatings. SEM images in figure 11 show that diamond contact virtually polishes the diamond surfaces. The evidence of diamond coating in the polished area was analyzed by Raman spectroscopy. It was found that both in the wear track (polished area) and in the area away from it, the characteristic diamond Raman spectra remain proving that no coating delamination occurred after the wear test. Some evidence of wear was found only in the Ti-6Al-4V pins but not in the disks when we use only USND layer to coat both the pins and disks. These results confirm our earlier wear study [23] with multilayer coatings (micro diamond using H2/CH4 and nanodiamond using H2/CH4/N2) approach and proved the hypothesis that multilayer diamond coated Ti-6Al-4V wear couple might have better performance when we consider diamond against diamond articulating surfaces.

Figure 9.

The wear rate of four USND coated titanium alloy articulating against polyethylene. The wear rate of CoCrMo against polyethylene is also shown for comparison.

Figure 10.

The wear factor k for USND coated titanium alloy and CoCrMo articulating against polyethylene.

Figure 11.

SEM images showing the wear pattern (polished surface) on multilayer diamond coating after wear test. Raman spectra on the diamond coating showing the evidence of diamond layer both in the wear track (point A) and away from the wear track (point B). Multilayer geometry (combined with micro, nano and USND diamond layers) is also shown.

It has been previously claimed that C2 species are responsible for producing nanocrystalline diamond. In this work we found that we can grow nanostructured diamond with a very low concentration of C2 dimers proving that C2 is not responsible for growing nanostructured diamond. CN radical in the plasma was the dominant species in our effort to produce the nanostructured diamond coating using H2/CH4/N2/He feed gases. With the change of plasma chemistry we can control CN species concentration in the plasma. Our results show that with the increase of CN species concentration in the plasma we can grow ultra small grain sized diamond. Small amount of CN and HCN in conventional mixture (H2/CH4) effectively abstract absorbed H atoms, creating vacant growth sites, thereby reducing carbon supersaturation. The larger amounts of CN and HCN resulted in excessive abstraction of adsorbed H which leaves the surface open to further adsorption by CN or other nitrogen species that are not able to stabilize the diamond structure efficiently [24]. Therefore, higher CN species concentration promotes higher nanocrystallinity. Higher CN species concentration also promotes poisoning of diamond growth resulted nanostructured diamond. Helium also has a strong influence on increase of the CN radical which control the degree of diamond nanocrystallinity. Helium addition reduced the diamond grain size and this suggests that the rate of secondary nucleation/renucleation increases in He/H2/CH4/N2 plasma, terminating the growth of large diamond nanocrystals [9]. Diamond coatings deposited with different CN concentration in the plasma were analyzed by AFM, Raman, glancing angle XRD, nanoindentation technique etc. Films grown with higher CN species concentration in the plasma produced smoother and nanostructured diamond coating without compromising the mechanical properties. Therefore CN might be responsible for producing nanostructured diamond coating using H2/CH4/N2/He feed gases.

Conclusions

We have deposited ultra smooth nanostructured diamond (USND) coatings on Ti-6Al-4V using H2/CH4/N2/He by microwave plasma deposition technique. We demonstrate that with the increase of CN species (normalized by Balmer Hα line) in the plasma we can deposit ultra smooth diamond coatings. Roughness as low as 4 nm and grain size of 5–6 nm were achieved using the plasma which gives highest CN species concentration. It has been previously claimed that C2 species is responsible for producing nanocrystalline diamond. In this work we found that we can grow nanostructured diamond with a very low concentration of C2 dimers proving that C2 is not responsible for growing nanostructured diamond. Diamond coatings deposited with different CN concentration in the plasma were analyzed by AFM, Raman, glancing angle XRD, nanoindentation technique. The characterization results proved that the films grown with higher CN species concentration in the plasma produced smoother and nanostructured diamond coating without compromising the mechanical properties. Therefore, it is suggested that the presence of CN species could be responsible for producing nanocrystallinity in the growth of USND coatings using He/H2/CH4/N2 gas mixture. Wear properties of these USND coating were also promising. All of the diamond (USND) coated Ti-6Al-4V disks had better wear performance against polyethylene compare to CoCrMo and polyethylene wear couple. In diamond-on-diamond wear tests, multilayer diamond coated Ti-6Al-4V wear couple (both pin and disk) have better wear performance than single layer USND coated wear couple (pin and disk) proving the hypothesis that multilayer diamond coated Ti-6Al-4V wear couple might have better performance when we consider diamond against diamond articulating surfaces.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Grant No. R01 DE013952. Patrice Johnson also acknowledges support from the National Science Foundation (NSF), Research Experiences for Undergraduates (REU) - site award under DMR-0646842.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/fact/thr_report.cfm?Thread_ID=504&topcategory=Hip http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/fact/thr_report.cfm?Thread_ID=472&topcategory=Knee

- 2.Saha S, Campbell C, Sarma A, Christiansen R. Crit Rev Biomed Eng. 2000;28:399. doi: 10.1615/critrevbiomedeng.v28.i34.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shankland WE. TMJ: Its Many faces. 2. Anadem; 1998. p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gruen DM. Annu Rev Sci. 1999;29:211. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soga T, Sharda T, Jimbo T. Physics of the Solid State. 2004;46:720. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gruen DM, Pan X, Krauss AR, Liu S, Luo J, Foster CM. J Vac Sci Technol A. 1994;12:1491. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rabeau JR, John P, Wilson JIB. J Appl Phys. 2004;96:6724. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Catledge SA, Vohra YK. In: Mechanical Properties of Structural Films. Muhlstein CL, Brown ST, editors. ASTM STP1413; West Conshohocken, PA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Konovalov VV, Melo A, Catledge SA, Chowdhury S, Vohra YK. J of Nanosci and Nanotechnol. 2006;6:258. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2006.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chowdhury S, Hillman Damon A, Catledge Shane A, Konovalov Valery V, Vohra Yogesh K. J Mater Res. 2006;21:2675. doi: 10.1557/JMR.2006.0334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fabes BD, Oliver WC, McKee RA, Walker FJ. J Mater Res. 1992;7:3056. [Google Scholar]

- 12.McHargue J. In: Applications of Diamond Films and Related Materials. Tzeng Y, Yoshikawa M, Murakawa M, Feldman A, editors. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1991. p. 113. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oliver WC, Pharr GM. J Mater Res. 1992;7:1564. [Google Scholar]

- 14.ASTM F732 – 00. Standard test method fro wear testing of polymeric materials used in total joint prostheses. Philadelphia, PA: 2003. p. 269. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hill MR, Konovalov V, Etheridge BS, Catledge SA, Chowdhury S, Clem W, Stanishevsky A, Lemons JE, Vohra YK, Eberhardt AW. J Biomed Mat Res B: Appl Biomater. 2007 doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30926. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bragdon CR, O’Conner DO, Lowenstein JD, Jasty M, Syniuta WD. IMechE Part H: J Engg Med. 1996;210:157. doi: 10.1243/PIME_PROC_1996_210_408_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saikko V, Calonius O, Keranen J. J Biomed Mat Res B: Appl Biomater. 2004;69B:141. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.20043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Afzal A, Rego CA, Ahmed W, Cherry RI. Diamond Relat Mater. 1998;7:1033. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tamor MA, Vassell WC. J Appl Phys. 1994;76:3823. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nemanich J, Glass JT, Lucovsky G, Shroder RE. J Vac Sci Technol A. 1988;6:1783. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leyland A, Matthews A. Wear. 2000;246:1. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halling J. Surface films in tribology. Tribologia. 1982;1:15. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Papo MJ, Catledge SA, Vohra YK. J Mat Sci-Mat In Medicine. 2004;15:773. doi: 10.1023/b:jmsm.0000032817.05997.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bohr S, Haubner R, Lux B. Appl Phys Lett. 1996;68:1075. [Google Scholar]