Abstract

Species responses to climate change may be influenced by changes in available habitat, as well as population processes, species interactions and interactions between demographic and landscape dynamics. Current methods for assessing these responses fail to provide an integrated view of these influences because they deal with habitat change or population dynamics, but rarely both. In this study, we linked a time series of habitat suitability models with spatially explicit stochastic population models to explore factors that influence the viability of plant species populations under stable and changing climate scenarios in South African fynbos, a global biodiversity hot spot. Results indicate that complex interactions between life history, disturbance regime and distribution pattern mediate species extinction risks under climate change. Our novel mechanistic approach allows more complete and direct appraisal of future biotic responses than do static bioclimatic habitat modelling approaches, and will ultimately support development of more effective conservation strategies to mitigate biodiversity losses due to climate change.

Keywords: population viability analysis, bioclimatic envelope, niche model, uncertainty, fynbos, fire

1. Introduction

Threats to biodiversity posed by the twenty-first century climate change create an imperative for assessments of extinction risk for planning species-level conservation. Species responses to climate change are likely to depend on interactions between population processes (Maschinski et al. 2006), between species (Araújo & Luoto 2007) and between demographic and landscape dynamics (Wintle et al. 2005). For example, Akçakaya et al. (2004) found that species persistence in a changing landscape depends on the balance between the rate of appearance and spatial arrangement of habitat patches, as well as the species' capacity for reproduction and dispersal.

A common approach for predicting species' responses to climate change involves use of habitat suitability (HS) models or ‘bioclimatic envelopes’. These models use present-day species–climate relationships (though they may also include non-climatic habitat predictors) to project potential distributions of species under future climates (Pearson & Dawson 2003). However, the predictions of species responses based solely on projected changes in the availability of suitable habitat are bound to be incomplete because they fail to account for important processes that influence extinction outcomes (Pearson & Dawson 2003; Akçakaya et al. 2006; Thuiller et al. 2008). Furthermore, shifts and contractions of suitable climates do not easily translate into extinction risks (Thuiller et al. 2004). Consequently, methodological problems have been identified in several recent attempts to infer extinction rates or levels of threat based solely on bioclimatic models (Buckley & Roughgarden 2004; Hampe 2004; Akçakaya et al. 2006).

Predictions may be made more accurate by developing models that incorporate interactions among habitat shifts, landscape structure and demography. Population viability models offer an explicit stochastic framework for such analysis (Maschinski et al. 2006; Saltz et al. 2006), yet spatial applications have not been developed to their full potential as a means of seeking generalizations about climate change impacts on large numbers of species.

In this study, we developed a novel mechanistic synthesis of spatial dynamics and demographic processes. Our approach links dynamic HS models with spatially explicit stochastic population models to determine how variations in life history, disturbance regime and distribution patterns influence the viability of populations under stable and changing climate scenarios. We applied this approach to predict impacts of climate change on plant population viability in South African fynbos, one of the world's biodiversity hot spots.

2. Material and methods

(a) Habitat suitability models

Generalized additive models were constructed for 234 species using spatially explicit presence/absence records (1′×1′ spatial resolution) from the Protea Altas (Rebelo 2002) and spatial data for five climate and three substrate variables (see Midgley et al. 2003). Models were calibrated in Biomod (Thuiller 2003) using a random sample of the initial data (70%), stepwise variable selection and the Akaike information criterion to select the most parsimonious model. Each model was evaluated on the remaining 30% of the data using the area under the curve of a receiver operating characteristic plot. HS maps for the years 2000, 2030 and 2050 were derived from the models using the projected IS92a climate scenario from the HadCM2 global circulation model (Houghton et al. 1996). A time series of HS maps for each year from 2000 to 2050 was then derived by linear interpolation. Three species representing contrasting patterns of distribution change were selected from the 234 modelled species: A, widespread range undergoing large contraction (represented by Protea neriifolia); B, restricted range contracting at the margins but with HS increasing in the core (Leucadendron laureolum); and C, restricted range undergoing shift and fragmentation (Leucadendron levinsianus).

(b) Stochastic population models

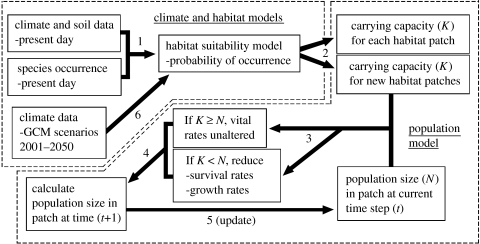

Population models were constructed for two contrasting plant life histories: a serotinous obligate seeding shrub (all standing plants killed by fire, mature seeds retained in woody fruits and dispersed by wind); and a myrmecochorous resprouting shrub (some plants survive fire, seeds released when mature and cached by ants). In both cases, seedling recruitment is cued to fire. Spatially explicit age/stage-based matrix models were constructed in Ramas Gis (Akçakaya & Root 2005) and parametrized using demographic studies of Cape Proteaceae and related species (see electronic supplementary material). The models included recurring fires, seed dispersal, and environmental and demographic stochasticity. Density dependence (DD) was implemented using a ceiling model to reduce survival and growth independently for particular life stages whenever a population exceeds the carrying capacity (K) of its habitat patch. K was determined from modelled probability of occurrence. Climate change may alter K, as determined by the time series of HS models. Thus, if climate change reduces K below population size, vital rates are reduced until the population falls below K (figure 1). If climate change increases K or creates new habitat patches, then the population response is governed by its density-independent vital rates and seed dispersal probability function.

Figure 1.

Coupling of dynamic HS models with a stochastic population model. Each simulation commences with step 1. After the first iteration is completed at step 5, second and subsequent iterations commence with step 6 in lieu of step 1.

(c) Simulations

Population viability under the climate change scenario was compared with that for a stable climate scenario (K held constant at year 2000 levels). This was done for factorial combinations of two plant life-history types, three distribution patterns, two fire regimes (mean intervals of 8 and 14 years), two methods for determining K (dependent on HS and habitat area (HA) or only HA) and two density-dependence models (one affecting all stages evenly and the other with smaller impacts on mature plants than other stages). For the wind-dispersed obligate seeder, we modelled two seed dispersal functions from different datasets representing a plausible range of dispersal capability.

All simulations were based on 1000 replicates, each for 50 years, i.e. 2001–2050. The viability of species' populations was assessed using expected minimum abundance (EMA; McCarthy & Thompson 2001) and the probability that the population would fall below 50% of its initial abundance. We evaluated variation in the latter using a logit-linear model.

3. Results

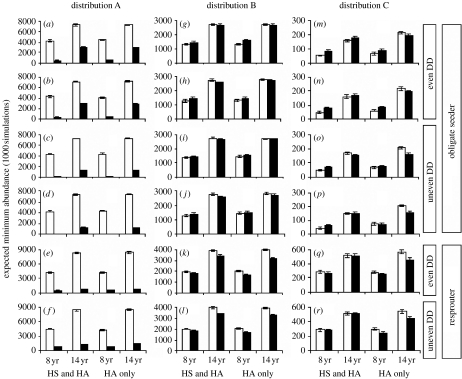

Species responses to climate change exhibited complex dependencies on all factors examined. Two highly significant fourth-order interactions in the logit-linear model indicated that the probability of population decline under climate change was dependent on distribution pattern, life history, evenness of density-dependence effects across life stages and fire regime (table S3 in the electronic supplementary material). EMA exhibited a similarly complex response (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Variation in population viability (EMA) for stable climate (open bars) and changing climate (closed bars) scenarios during 2000–2050. Error bars are 95% CIs across 1000 simulations. Modelled scenarios for three patterns of distribution change (A, widespread contracting; B, restricted contracting at margins and increasing suitability in core; C, restricted shifting and fragmenting), two life-history types (obligate seeder, resprouter), three modes of seed dispersal ((a,c,g,i,m,o) wind (long); (b,d,h,j,n,p) wind (short); and (e,f,k,l,q,r) ant), two types of DD (DD even, DD uneven across stages), two types of carrying capacity (HS and HA, HA only) and two fire regimes (mean fire intervals of 8 and 14 years).

The most robust generalization emerging from our simulations was that species populations were more viable under 14-year mean fire intervals than under 8-year intervals. With few exceptions, EMA was approximately double under the less frequent fire regime, irrespective of climate change and other factors (figure 2).

Species with widespread but contracting distributions (pattern A) had the most marked decline in population viability under climate change (figure 2). While viability was reduced under climate change for both life-history types, longer fire intervals mitigated the impact more for the serotinous obligate seeder than for the myrmecochorous resprouter.

For the species exhibiting other patterns of distribution (B and C), complex interactions between life history, fire frequency and the determinants of carrying capacity governed differences in response to stable and changing climate scenarios. Figure 2m illustrates one example of these interactions. Relative to a stable climate scenario, climate change increased population viability under mean fire intervals of 8 years, but reduced viability under 14-year fire intervals. This interaction exists when K depends on HA only but not when it depends on both HS and HA.

The two life histories responded to climate change differently, depending on whether DD acted differentially across life stages. For the serotinous obligate seeder, populations were generally more viable when density-dependent impacts on growth and survival affected life stages evenly than if impacts were greater on seedling, juvenile and senescent stages, although differences were relatively small and there were several exceptions. For the myrmecochorous resprouter, the relationship tended to be reversed, with some exceptions.

Responses to climate change were relatively unaffected by alternative models of dispersal for the wind-dispersed serotinous obligate seeder, suggesting that the levels of dispersal required to offset movement of bioclimatic envelopes are beyond the biologically plausible bounds of dispersal for these species. For distribution pattern (C), both long- and short-dispersal models produced zero dispersal probabilities between all present-day populations although viability for the other distributions was marginally improved when probabilities of long-distance movement were increased.

4. Discussion

Our study demonstrates the feasibility of linking spatial and demographic dynamics, for species where both life-history and habitat requirements are well understood. Our population models are detailed, yet generic in the sense that they apply to relatively large groups of functionally similar species. With minor adjustments to parameter estimates, they can offer realistic representations for analysis of large numbers of species. Combined with already well-developed protocols for producing large ensembles of HS models (Araújo & New 2007), they offer a powerful mechanistic approach for assessing extinction risks posed by climate change. By addressing population mechanisms directly, our approach avoids assumptions that oversimplify the relationship between habitat change and extinction processes, such as those inferring rates of species loss from species-area patterns (Buckley & Roughgarden 2004; Thuiller et al. 2004).

Our results indicate that complex interactions between life history, disturbance regime and distribution pattern mediate whether particular species will be exposed to increased extinction risks under future climate scenarios. This underscores the need for methods that link spatial and demographic processes. In isolation, population and habitat models fail to deal with interactions and dependencies between small-scale population processes and landscape-scale habitat change. Coupled together (figure 1), they are more likely to produce projections that are both realistic and robust to uncertainty. This creates an imperative to improve quantitative understanding of demographic processes in relation to climatic variation. Without reliable primary data, errors in the structure and parametrization of population models could compromise prediction of climate change impacts on species and hence management strategies for their conservation.

Our approach allows incorporation of several factors likely to exacerbate or mitigate the effects of climate change on species viability beyond those predicted by changes in available HA. These factors include spatial heterogeneity in species distributions (Shoo et al. 2005), interaction of range shifts with land-use change, isolation and barriers to dispersal, increased frequency of extreme weather events or fires and increased spatial correlation of population dynamics. In practice, the availability of data will determine which of these factors can be incorporated into extinction risk assessments.

In future work, our approach can be expanded to analyse a broader range of organisms and other climatic regions to seek robust generalizations about the susceptibility of species to global climate change. Our mechanistic approach will ultimately support the development of more effective conservation strategies to mitigate losses of biodiversity from global climate change.

Acknowledgments

This work arose from a workshop funded by NERC Centre for Population Biology, ‘Using IUCN Red List Criteria to Project Climate Change Impacts on Biodiversity’. W.T. and M.B.A. received support from EC FP6 MACIS (no. 044399). Contribution 1162 in Ecology and Evolution, Stony Brook University.

Footnotes

One contribution of 12 to a Special Feature on ‘Global change and biodiversity: future challenges’.

Supplementary Material

Model structure and parameterisation

References

- Akçakaya H.R, Radeloff V.C, Mladenoff D.J, He H.S. Integrating landscape and metapopulation modeling approaches: viability of the sharp-tailed grouse in a dynamic landscape. Conserv. Biol. 2004;18:526–537. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2004.00520.x [Google Scholar]

- Akçakaya H.R, Butchart S.H.M, Mace G.M, Stuart S.N, Hilton-Taylor C. Use and misuse of the IUCN Red List Criteria in projecting climate change impacts on biodiversity. Glob. Change Biol. 2006;12:2037–2043. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2006.01253.x [Google Scholar]

- Akçakaya, H. R. & Root, W. T. 2005 Ramas Gis: linking spatial data with population viability analysis, version 5.0. Setauket, NY: Applied Biomathematics.

- Araújo M.B, Luoto M. The importance of biotic interactions for modelling species distributions under climate change. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2007;16:743–753. doi:10.1111/j.1466-8238.2007.00359.x [Google Scholar]

- Araújo M.B, New M. Ensemble forecasting of species distributions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2007;22:42–47. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2006.09.010. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2006.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley L.B, Roughgarden J. Effects of changes in climate and land use. Nature. 2004;430:34. doi: 10.1038/nature02717. doi:10.1038/nature02717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampe A. Bioclimate envelope models: what they detect and what they hide. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2004;13:469–471. doi:10.1111/j.1466-822X.2004.00090.x [Google Scholar]

- Houghton J.T, Meria Filho L.G, Callander B.A, Harris N, Kattnberg A, Maskell K. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 1996. Climate change 1995: the science of climate change. [Google Scholar]

- Maschinski J, Baggs J.E, Quintana-Ascencio P.F, Menges E.S. Effects of climate change on the extinction risk of an endangered limestone endemic shrub, Arizona cliffrose. Conserv. Biol. 2006;20:218–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00272.x. doi:10.1111/j.1523.1739.2006.00272.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy M.A, Thompson C. Expected minimum population size as a measure of threat. Anim. Conserv. 2001;4:351–355. doi:10.1017/S136794300100141X [Google Scholar]

- Midgley G.F, Hannah L, Millar D, Thullier W, Booth A. Developing regional and species-level assessments of climate change impacts on biodiversity in the Cape Floristic Region. Biol. Conserv. 2003;112:87–97. doi:1016/S0006-3207(02)00414-7 [Google Scholar]

- Pearson R.G, Dawson T. Predicting the impact of climate change on species distribution: are bioclimate envelope models useful? Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2003;12:361–371. doi:10.1046/j.1466-822X.2003.00042.x [Google Scholar]

- Rebelo A.G. 2nd edn. Fernwood Press; Vlaeberg, Republic of South Africa: 2002. Proteas. A field guide to the Proteas of southern Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Saltz D, Rubenstein D.I, White G.C. The impact of increased environmental stochasticity due to climate change on the dynamics of asiatic wild ass. Conserv. Biol. 2006;20:402–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00486.x. doi:10.1111/j.1523.1739.2006.00486.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoo L.P, Williams S.E, Hero J.-M. Potential decoupling of trends in distribution area and population size of species with climate change. Glob. Change Biol. 2005;11:1469–1476. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2005.00995.x [Google Scholar]

- Thuiller W. Biomod: optimising predictions of species distributions and projecting potential future shift under global change. Glob. Change Biol. 2003;9:1353–1362. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12728. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2486.2003.00666.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thuiller W, Araújo M.B, Pearson R.G, Whittaker R.J, Brotons L, Lavorel S. Uncertainty in predictions of extinction risk. Nature. 2004;430:33. doi: 10.1038/nature02716. doi:10.1038/nature02716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thuiller W, et al. Predicting global change impacts on plant species' distributions: future challenges. Persp. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2008;9:137–152. doi:10.1016/j.ppees.2007.09.004 [Google Scholar]

- Wintle B, Bekessy S.A, Venier L.A, Pearce J.L, Chisholm R.A. Utility of dynamic-landscape metapopulation models for sustainable forest management. Conserv. Biol. 2005;19:1930–1943. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00276.x [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Model structure and parameterisation