Abstract

The tribe Bovini contains a number of commercially and culturally important species, such as cattle. Understanding their evolutionary time scale is important for distinguishing between post-glacial and domestication-associated population expansions, but estimates of bovine divergence times have been hindered by a lack of reliable calibration points. We present a Bayesian phylogenetic analysis of 481 mitochondrial D-loop sequences, including 228 radiocarbon-dated ancient DNA sequences, using a multi-demographic coalescent model. By employing the radiocarbon dates as internal calibrations, we co-estimate the bovine phylogeny and divergence times in a relaxed-clock framework. The analysis yields evidence for significant population expansions in both taurine and zebu cattle, European aurochs and yak clades. The divergence age estimates support domestication-associated expansion times (less than 12 kyr) for the major haplogroups of cattle. We compare the molecular and palaeontological estimates for the Bison–Bos divergence.

Keywords: divergence times, demographic model, population expansion, ancient DNA, time dependency

1. Introduction

Domestic animals and crops not only possess economic, cultural and religious values, but they also represent intriguing case studies for evolutionary biologists due to their distinctive selective and demographic histories. The tribe Bovini (Family Bovidae, Subfamily Bovinae) contains several species of interest, including domesticated cattle (both taurine and zebu) and yak. Abundant sequence data have been produced by recent studies of bovine domestication (e.g. Loftus et al. 1994; Bailey et al. 1996; Bradley et al. 1996; Troy et al. 2001; Bollongino et al. 2006; Edwards et al. 2007), making it possible to use sophisticated phylogenetic methods to test hypotheses about the domestication process (e.g. Finlay et al. 2007).

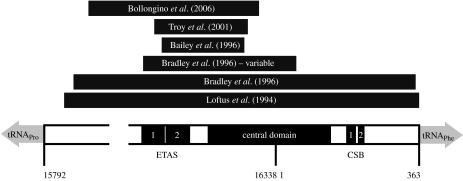

An accurate time scale for bovine evolution is important for distinguishing between the genetic signatures left by domestication (approx. 10 kyr ago; Dobney & Larson 2006) and post-glacial expansion following the Last Glacial Maximum (approx. 20 kyr ago; Hewitt 2000). There have been substantial disparities among the published estimates of bovine divergence times, however, leaving the time scale relatively unclear. Undoubtedly, some of these variations have arisen from differences in the phylogenetic methods, calibration points and sequence alignments that have been used (figure 1).

Figure 1.

The bovine D-loop, with positions labelled according to the Bos taurus reference sequence (GenBank accession number V00654). The extended termination-associated sequence (ETAS), central domain and conserved sequence block (CSB) are labelled. Dark grey bars represent the segments analysed in the previous studies of bovines, including the 370 bp hypervariable region targeted by Bradley et al. (1996).

Overall, the bovine species complex presents a number of methodological difficulties, including the absence of reliable fossil calibrations for estimating divergence times. Deep palaeontological calibration points are possibly inappropriate for studying the evolution of such closely related species (Ho et al. 2005), while previous studies have frequently adopted published estimates for divergence times or substitution rates without due appreciation of the associated estimation error. For example, Finlay et al. (2007) used a Bayesian demographic analysis to find evidence of population expansion in domesticated bovine species but were unable to attach a reliable time scale. Although their analyses suggested that population growth occurred within the past 10 kyr, they assumed an errorless, tree-wide substitution rate of 32% per Myr, even though the original estimate came with a 95% highest posterior density (HPD) of 23–41% per Myr (Shapiro et al. 2004).

The recent proliferation of ancient DNA sequences from multiple bovine species offers an unprecedented opportunity to analyse the molecular evolutionary process in detail. Radiocarbon-dated samples can act as internal time calibrations for estimating rates and divergence times. In this study, we employ a Bayesian phylogenetic method that assigns a separate demographic model to different clades in the tree, allowing multiple species to be studied simultaneously. This method is used to analyse a dataset containing 481 mitochondrial D-loop sequences from five bovine species, including 228 radiocarbon-dated ancient DNA sequences. We produce an internally calibrated estimate of the evolutionary time scale and bovine phylogeny.

2. Material and methods

Published nucleotide sequences were obtained from the D-loop of five bovine species and were aligned manually. The dataset comprised 476 aligned sites from 481 individuals (table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of the mitochondrial D-loop alignment analysed in this study.

| number of sequences | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| species | modern | ancient | age range (years) | |

| European aurochs | Bos primigenius | 0 | 34 | 2000–11 930 |

| bison | Bison bison | 82 | 158 | 0–60 400 |

| taurine cow | Bos taurus | 91 | 36 | 0–8065 |

| yak | Bos grunniens | 50 | 0 | — |

| zebu cow | Bos indicus | 30 | 0 | — |

| total | 253 | 228 | 0–60 400 | |

Bayesian phylogenetic analysis was performed using Beast v. 1.4.6 (available from http://beast.bio.ed.ac.uk) using TIM+I+G substitution model as selected by comparison of Akaike Information Criterion scores. The analysis was repeated using the TIM+G model to investigate the influence of the parameter describing the proportion of invariant sites. Temporal information was incorporated into the analysis by including radiocarbon dates for ancient sequences, allowing the estimation of the age of the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) for bovine clades. A separate demographic model of exponential growth was applied, in the form of a coalescent prior, to each of the five species; the population size and growth rate were estimated in each case. An uninformative tree prior was used for the basal branches connecting the five species. An uncorrelated lognormal relaxed clock was used to accommodate possible rate variations among lineages (Drummond et al. 2006). In the Markov chain Monte Carlo analysis, samples from the posterior were drawn at every 5000 steps over a total of 50 000 000 steps, following a discarded burn-in of 5 000 000 steps. The analysis was repeated and the samples from the two runs were combined. Sampling, mixing and convergence to the stationary distribution were checked. The Beast input file, which includes sample names and ages, is available as electronic supplementary material.

3. Results

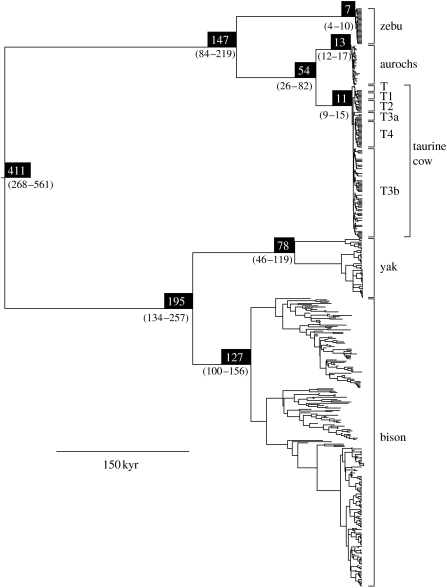

Bayesian phylogenetic analysis of the complete dataset produced a tree with 100% posterior support for the monophyly of each species (table 2), and with strong support for higher level nodes (figure 2). The inferred phylogeny confirms the results of previous mitochondrial studies, including the pairing of American bison (Bison bison) with yak (Bos grunniens; Hassanin & Douzery 1999; Verkaar et al. 2004) and the reciprocal monophyly of European aurochsen and taurine cattle (Troy et al. 2001; Edwards et al. 2007). Among taurine cattle, there was evidence for monophyly of haplogroups T1, T2 and T4 (table 2), but not for haplogroups T and T3.

Table 2.

Divergence time estimates for the bases of various bovine clades, made with and without assuming a proportion of invariant sites

| clade | divergence time (years)a | number of sequences | clade posterior probability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| with invariant sites | without invariant sites | |||

| European aurochs | 13 000 (11 900–17 700) | 12 500 (11 900–14 600) | 34 | 1.00 |

| bison | 127 000 (99 800–154 000) | 122 000 (97 400–148 000) | 240 | 1.00 |

| taurine cow | 11 200 (8590–14 700) | 10 600 (8840–12 700) | 127 | 1.00 |

| haplogroup T1 | 6490 (4410–9910) | 5780 (4150–7460) | 6 | 0.90 |

| haplogroup T2 | 6840 (5020–8780) | 6480 (4960–8090) | 10 | 1.00 |

| haplogroup T4 | 6930 (5350–8530) | 6570 (5390–7750) | 22 | 1.00 |

| yak | 78 400 (45 100–117 000) | 74 400 (41 200–110 000) | 50 | 1.00 |

| zebu cow | 7290 (4550–11 700) | 6480 (3840–9180) | 30 | 1.00 |

| aurochs+taurine cow | 53 800 (26 200–81 900) | 49 000 (25 900–76 300) | 161 | 1.00 |

| aurochs+taurine cow+zebu cow | 147 000 (84 300–219 000) | 129 000 (72 000–191 000) | 191 | 1.00 |

| bison+yak | 195 000 (134 000–257 000) | 185 000 (127 000–244 000) | 290 | 1.00 |

| all | 411 000 (269 000–564 000) | 374 000 (240 000–531 000) | 481 | 1.00 |

Mean estimate, with 95% HPD given in parentheses. All estimates are given to three significant figures.

Figure 2.

Maximum clade credibility tree estimated using Bayesian analysis of 481 mitochondrial D-loop sequences from five bovine species, using the TIM+I+G substitution model. Numbers above nodes denote mean estimates of divergence times (kyr), with numbers below nodes showing the 95% HPD. The posterior probability of all the labelled nodes was 1.0. All branch lengths are scaled according to time; tips that do not reach the present represent ancient samples.

Estimates of the growth rate parameter for the five demographic models revealed significant evidence for population expansion in taurine and zebu cattle, and aurochsen, but not in bison or yaks. The result for aurochs is consistent with the findings of Edwards et al. (2007), where an exponential growth model provided a better fit to the data than a model assuming constant population size. Although our result for yak appears to differ from the qualitative result obtained by Finlay et al. (2007), we detect significant population expansions when the three major intraspecific clades are treated as separate populations (results not shown), with an average estimated age of 11 160 years. This treatment might be more appropriate due to the complex demographic history of yaks. There is evidence to suggest that Pleistocene climatic cycling between glacial and interglacial periods caused yaks to alternate between fragmented and contiguous interbreeding populations, resulting in large intra-population divergences within modern yaks (Guo et al. 2006). Therefore, the common ancestor of all yak lineages predates the most recent range expansion and does not correspond to the advent of domestication; instead, our mean age estimate for the common ancestor of yak mtDNA (approx. 75 kyr BP) coincides with the onset of the European Weichselian glaciation.

The coefficient of variation of rates among branches was 0.025 (95% HPD: 0.000–0.075) with invariant sites and 0.044 (95% HPD: 0.000–0.116) without invariant sites, suggesting that there is no significant departure from the assumption of a global molecular clock. When a proportion of invariant sites was assumed, the average substitution rate across the tree was estimated at 5.89×10−7 substitutions per site per year (95% HPD: 4.66×10−7–7.10×10−7 substitutions per site per year), equivalent to 58.9% per Myr. This dropped slightly to 5.68×10−7 substitutions per site per year (95% HPD: 4.31×10−7–7.02×10−7 substitutions per site per year) when the invariant sites' parameter was omitted.

Date estimates were made for the MRCAs of various bovine species and clades (table 2). The removal of the parameter for invariant sites had only a very small effect on most of the estimated dates. Collectively, they present a shorter time scale for bovine evolution than that suggested by previous studies. The estimated age of the root was 411 kyr (95% HPD: 269–564 kyr) with invariant sites and 374 kyr (95% HPD: 240–531 kyr) without invariant sites.

4. Discussion

Our results support a relatively contracted time frame for bovine evolution. For all major haplogroups of taurine and zebu cattle, basal divergence times were significantly more recent than 15 kyr ago, supporting the hypothesis of a domestication-associated population expansion. The molecular age estimates are consistent with the earliest evidence of domestic taurine cattle in the Near East, dating from the eighth millennium BC (Peters et al. 1999), and of zebu cattle in the fifth millennium BC (Bökönyi 1997). By contrast, the European aurochs seems to have experienced population growth concurrent with glacial retreat in Europe. The estimated age of the MRCA of all bison was very similar to that obtained by Shapiro et al. (2004), despite the differences in datasets and methodology.

The estimate for the age of the root of the tree is considerably younger than the 1 Myr Bison–Bos calibration point frequently used in the studies of cattle domestication (e.g. Bradley et al. 1996; Troy et al. 2001). The fossil record supports an older date for the Bison–Bos split, which falls between the first appearance of stem-lineage bovines at around 8.9 Myr (Barry et al. 2002) and the earliest representative of Bison dating from 2 to 2.5 Myr (Tedford et al. 1991). Overall, this suggests that it might not be appropriate to estimate dates for deeper, interspecific splits using aDNA-based calibrations at the tips of the tree, and that fossil-based calibrations at internal nodes might be preferable. Given the time dependency of rates (Ho et al. 2005), it might be advisable to employ a combination of the two calibration types to allow for higher rates towards the tips of the tree and lower rates in the basal branches.

Our internally calibrated phylogenetic analysis using multiple demographic models has yielded significant evidence of population expansion in a number of bovine species. The expansions in taurine and zebu cattle appear to coincide with domestication rather than post-glacial climatic changes. Further mitochondrial and nuclear data will serve to improve the precision of the current set of date estimates, allowing a more detailed insight into the evolutionary history of bovines.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Australian Research Council, the Leverhulme Trust and the Royal Society. We are grateful to Alexei Drummond and Andrew Rambaut for making it possible to use multiple coalescent priors in their software Beast, Alan Cooper for assistance and three anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback.

Supplementary Material

Bovine input file for Bayesian phylogenetic software Beast

References

- Bailey J.F, Richards M.B, Macaulay V.A, Colson I.B, James I.T, Bradley D.G, Hedges R.E, Sykes B.C. Ancient DNA suggests a recent expansion of European cattle from a diverse wild progenitor species. Proc. R. Soc. B. 1996;263:1467–1473. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1996.0214. doi:10.1098/rspb.1996.0214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry J.C, et al. Faunal and environmental change in the late Miocene Siwaliks of northern Pakistan. Paleobiology. 2002;28:1–71. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2002)28[1:FAECIT]2.0.CO;2 [Google Scholar]

- Bökönyi S. Zebus and Indian wild cattle. Anthropozoologica. 1997;25/26:647–654. [Google Scholar]

- Bollongino R, Edwards C.J, Alt K.W, Burger J, Bradley D.G. Early history of European domestic cattle as revealed by ancient DNA. Biol. Lett. 2006;2:155–159. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2005.0404. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2005.0404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley D.G, MacHugh D.E, Cunningham P, Loftus R.T. Mitochondrial diversity and the origins of African and European cattle. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:5131–5135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.5131. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.10.5131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobney K, Larson G. Genetics and animal domestication: new windows on an elusive process. J. Zool. 2006;269:261–271. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2006.00042.x [Google Scholar]

- Drummond A.J, Ho S.Y.W, Phillips M.J, Rambaut A. Relaxed phylogenetics and dating with confidence. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e88. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040088. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards C.J, et al. Mitochondrial analysis shows a Neolithic Near Eastern origin for domestic cattle and no evidence of domestication of European aurochs. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2007;274:1377–1385. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.0020. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.0020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay E.K, et al. Bayesian inference of population expansions in domestic bovines. Biol. Lett. 2007;3:449–452. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2007.0146. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S, Savolainen P, Su J, Zhang Q, Qi D, Zhou J, Zhong Y, Zhao X, Liu J. Origin of mitochondrial DNA diversity of domestic yaks. BMC Evol. Biol. 2006;6:73. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-6-73. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-6-73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassanin A, Douzery E.J.P. The tribal radiation of the family Bovidae (Artiodactyla) and the evolution of the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 1999;13:227–243. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1999.0619. doi:10.1006/mpev.1999.0619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt G. The genetic legacy of the Quaternary ice ages. Nature. 2000;405:907–913. doi: 10.1038/35016000. doi:10.1038/35016000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho S.Y.W, Phillips M.J, Cooper A, Drummond A.J. Time dependency of molecular rate estimates and systematic overestimation of recent divergence times. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2005;22:1561–1568. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi145. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loftus R.T, MacHugh D.E, Bradley D.G, Sharp P.M, Cunningham P. Evidence for two independent domestications of cattle. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:2757–2761. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.7.2757. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.7.2757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J, Helmer D, von den Drisch A, Saña-Segui M. Animal domestication and husbandry in PPN northern Syria and south-eastern Turkey. Paléorient. 1999;25:27–47. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro B, et al. Rise and fall of the Beringian steppe bison. Science. 2004;306:1561–1565. doi: 10.1126/science.1101074. doi:10.1126/science.1101074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedford R.H, Flynn L.J, Zhanxiang Q, Opdyke N.D, Downs W.R. Yushe Basin, China: paleomagnetically calibrated mammalian biostratigraphic standard for the late Neogene of eastern Asia. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 1991;11:519–526. [Google Scholar]

- Troy C.S, MacHugh D.E, Bailey J.F, Magee D.A, Loftus R.T, Cunningham P, Chamberlain A.T, Sykes B.C, Bradley D.G. Genetic evidence for Near-Eastern origins of European cattle. Nature. 2001;410:1088–1091. doi: 10.1038/35074088. doi:10.1038/35074088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkaar E.L, Nijman I.J, Beeke M, Hanekamp E, Lenstra J.A. Maternal and paternal lineages in cross-breeding bovine species. Has wisent a hybrid origin? Mol. Biol. Evol. 2004;21:1165–1170. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh064. doi:10.1093/molbev/msh064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Bovine input file for Bayesian phylogenetic software Beast