Abstract

Necrotizing fasciitis due to Streptococcus pneumoniae is a rare and grave condition, and only a few cases have been reported. Suggested risk factors include minor trauma, systemic lupus erythematosus, immunosuppression secondary to medication, use of intramuscular anti-inflammatories and alcoholism. A fatal case of pneumococcal necrotizing fasciitis that occurred in a 51-year-old woman with a history of alcohol abuse and oral anti-inflammatory use is presented. Her condition was caused by a multi-etiology outbreak of community-acquired pneumonia, from which S pneumoniae serotype 5 was also isolated. The case description outlines the subtle presentation and rapid clinical progression of this condition. Because serotype 5 antigen is included in the polysaccharide 23-valent pneumococcal vaccine, the present case highlights the importance of pneumococcal immunization programs in Canada.

Keywords: Aboriginal, Canada, Necrotizing fasciitis, Streptococcus pneumoniae

Abstract

La fasciite nécrosante à Streptococcus pneumoniæ est une maladie grave et rare dont quelques cas seulement ont été signalés. Les facteurs de risque possibles incluent : traumatismes mineurs, lupus érythémateux disséminé, immunosuppression d’origine médicamenteuse, prise d’anti-inflammatoires intramusculaires et alcoolisme. On présente ici un cas fatal de fasciite nécrosante pneumococcique chez une femme de 51 ans qui avait des antécédents d’éthylisme et qui était traitée au moyen d’anti-inflammatoires. Sa maladie a été causée par une éclosion multi-étiologique de pneumonie d’origine communautaire où l’on a isolé le sérotype 5 de S. pneumoniæ. La description de ce cas met en lumière les subtilités du tableau clinique et la progression rapide de cette maladie. Étant donné que l’antigène du sérotype 5 est inclus dans le vaccin antipneumococcique polysaccharidique 23-valent, le présent cas rappelle l’importance des programmes d’immunisation antipneumococcique au Canada.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 51-year-old Aboriginal woman from northern Saskatchewan presented to a local family medical clinic in early October 2006 with a three-day history of left knee pain. Her vital signs included a blood pressure of 114/70 mmHg, a heart rate of 100 beats/min and a respiratory rate of 20 breaths/min. Her temperature was not documented. On examination, her knee was warm and painful, and an effusion was noted. Approximately six weeks prior, she had fallen on her right knee while walking. This injury was complicated by hemarthrosis and effusion, requiring needle drainage on two occasions. In addition, she had a history of pain, swelling and erythema involving her shoulder joint. Her past history was significant for alcohol abuse and unstable social and housing conditions. The laboratory results showed the following – white blood cell (WBC) count 9.8×109/L (normal 0.2×109/L to 10×109/L); granulocyte count 8.8×109/L (normal 2×109/L to 7.8×109/L); hemoglobin (Hb) level 102 g/L (normal 120 g/L to 180 g/L) and platelet count 68×109/L (normal 150×109/L to 450×109/L). A presumptive diagnosis of inflammatory arthritis was made, and she was given indomethacin 50 mg three times a day for her symptoms.

Two days later, the patient became progressively more confused, disoriented and unresponsive to questions. She was brought by ambulance to the local emergency department where her temperature was 38.8°C, pulse 98 beats/min, blood pressure 140/83 mmHg and respiratory rate 32 breaths/min. Her Glasgow coma scale score was 6. She was unresponsive to verbal commands but responsive to painful stimuli. Bruising was noted on both legs, and a large area of erythema was noted around the left knee. Her respiratory examination was unremarkable. Laboratory results showed the following – WBC count 3.7×109/L; Hb level 111 g/L; platelet count 171×109/L; sodium level 131 mmol/L (normal 137 mmol/L to 145 mmol/L); potassium level 3.2 mmol/L (normal 3.6 mmol/L to 5.0 mmol/L); chloride level 91 mmol/L (normal 98 mmol/L to 107 mmol/L); carbon dioxide 16 mmol/L (normal 22 mmol/L to 30 mmol/L); urea level 21.9 mmol/L (normal 2.5 mmol/L to 6.1 mmol/L); aspartate aminotransferase level 268 U/L (normal 8 U/L to 39 U/L); creatine kinase level 484 U/L (normal 30 U/L to 135 U/L) and creatine kinase isoenzyme – MB level 28 U/L (normal 0 U/L to 16 U/L). An evolving neurological condition was thought to be the primary diagnosis. Initial management included intravenous fluid (200 mL/h), cefotaxime 2 g administered intravenously, and blood cultures. She was transferred by air to the Royal University Hospital in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.

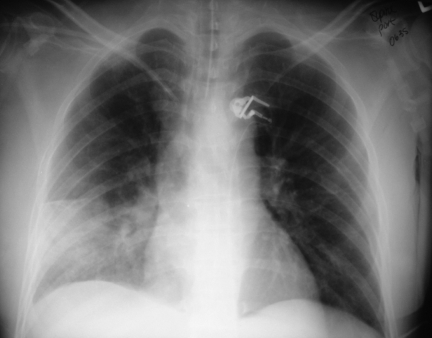

During the 1 h flight to Saskatoon, the area of erythema on her left leg tripled in size, and 3 L of intravenous fluids and dopamine were required to stabilize her blood pressure. On arrival, she was noted to be diffusely rigid with no response to painful stimuli. Her temperature was 39°C. She had rigors, peripheral mottling, absence of peripheral pulses, bronchial breath sounds over the right middle lobe, and erythema and target-like lesions over her left knee. Laboratory evaluation on admission showed the following – WBC count 3.2 ×109/L (normal 4×109/L to 11×109/L); Hb level 99 g/L (normal 110 g/L to 160 g/L); platelet count 144×109/L (normal 150×109/L to 400×109/L); creatine kinase level 894 U/L (normal 30 U/L to 200 U/L); creatine kinase isoenzyme – MB level 24 U/L (normal 0 U/L to 15 U/L); alkaline phosphatase level 53 U/L (normal 30 U/L to 110 U/L); alanine aminotransferase level 38 U/L (normal 5 U/L to 45 U/L); aspartate aminotransferase level 186 U/L (normal 10 U/L to 40 U/L); gamma glutamyl transferase level 80 U/L (normal 10 U/L to 35 U/L); sodium level 137 mmol/L (normal 135 mmol/L to 146 mmol/L); potassium level 3.3 mmol/L (normal 3.5 mmol/L to 5.1 mmol/L); chloride level 106 mmol/L (normal 100 mmol/L to 110 mmol/L); carbon dioxide 18 mmol/L (normal 22 mmol/L to 31 mmol/L); creatinine level 287 μmol/L (normal 45 μmol/L to 110 μmol/L); urea level 22.1 mmol/L (normal 3.7 mmol/L to 7.0 mmol/L); international normalized ratio 1.1 (normal 0.8 to 1.2) and partial thromboplastin time 29 s (normal 26 s to 36 s). Her chest x-ray demonstrated the presence of a large, right middle lobe infiltrate (Figure 1). Her knee aspiration yielded purulent fluid.

Figure 1.

Portable chest x-ray of a 51-year-old woman presenting with necrotizing fasciitis, toxic shock syndrome and community-acquired pneumonia in the absence of respiratory symptoms. Figure by Dr Ben Tan, Division of Infectious Diseases, Royal University Hospital, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan

A presumptive diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis (NF) of the left knee with toxic shock syndrome and pneumonia was made. Intravenous ceftriaxone (2 g every 12 h) and clindamycin (900 mg every 6 h) were administered.

She was immediately taken to the operating room for debridement of the leg, but due to the extent of involvement, she required left knee arthrotomy, followed by hip disarticulation and exploratory laparotomy. A frozen section of the iliac fascia revealed microscopic necrosis, but no bacteria were noted. Due to her worsening condition, a second laparotomy with anticipated debridement of the posterior abdomen and iliopsoas was considered, but could not be performed because of her family’s decision to withdraw care. The patient died on the second day of hospitalization.

Gram stain of pus from her knee revealed Gram-positive cocci. Streptococcus pneumoniae (serotype 5) was isolated from knee fluid, and blood and tissue cultures. The isolate was sensitive to penicillin, cefotaxime, clindamycin, fluoroquinolones and vancomycin, but was resistant to co-trimoxazole.

DISCUSSION

S pneumoniae is a Gram-positive diplococcus. There are 90 known serotypes, of which the top 10 account for over 60% of infections worldwide (1,2). Pneumococci can cause conjunctivitis, otitis media, community-acquired pneumonia and invasive infections such as sepsis, meningitis and soft tissue infections, among others. Transmission is primarily from person to person through respiratory droplets. People at both ends of the age spectrum are at a high risk of pneumococcal disease. Other risk factors include crowding, exposure to smoke, congenital or acquired immune deficiency, asplenia and a history of cochlear implants (3).

S pneumoniae serotype 5 is a common pneumococcal serotype in Africa and India (4). Since 2005, this strain has been identified with increasing frequency in Canada and has caused outbreaks of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) in Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba and Saskatchewan. Urban outbreaks in British Columbia and Alberta have involved inner-city, adult populations with risk factors for IPD – alcoholism, illicit drug use, history of hepatitis B or C and living in a housing shelter (5,6). Most individuals have severe disease – pneumonia with sepsis, with many requiring intensive care unit admission (5,6). Canadian Aboriginal people have a higher risk of IPD (7), and a higher risk of serotype 5 disease (OR 3.0, 95% CI 1.3 to 6.6) (5).

During October 2006, nine cases of IPD due to serotype 5 S pneumoniae were identified in an isolated community (population 3500) in northern Saskatchewan. Four IPD cases were in children younger than 10 years of age. These IPD cases formed part of a larger outbreak of multi-etiology community-acquired pneumonia, which included other agents such as Chlamydia pneumoniae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae and/or respiratory syncytial virus. The present case of NF is part of this outbreak.

S pneumoniae is a rare cause of NF, with approximately 12 cases documented in the literature (8–15). These case reports suggest the following risk factors for the development of pneumococcal NF – a history of diabetes, systemic lupus erythematosus, immunosuppression, alcohol use, coronary artery disease and administration of intramuscular nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (8,9,11–14). Only two cases of pneumococcal NF have been reported in healthy individuals who sustained minor trauma. One of these individuals used topical anti-inflammatory medication over the site of her injury which resulted in pruritus, scratching and subsequent excoriations. Whether the topical NSAID facilitated the progression of infection is unknown. NSAIDs are potent inhibitors of granulocyte function. In this case, the patient had used oral NSAIDs, which may have contributed to the accelerated course of illness; alternatively, they may have masked the symptoms, allowing her illness to progress (16).

Two different presentations of S pneumoniae NF have been identified – cellulitis of the upper body (face, neck and torso), usually accompanied by autoimmune (systemic lupus erythematosus) or hematological disorders, and fasciitis, predominantly involving the limbs and usually in association with coexisting diabetes mellitus or chronic alcohol use (14). While an antecedent history of trauma can be present in 75% of NF cases due to group A streptococcus, this feature is usually absent in NF due to S pneumoniae (14). Pneumococcal serotypes implicated in NF include 6A, 9, 9V, 10A and 14. Our case report is the first documentation of NF due to serotype 5.

Although S pneumoniae serotype 5 is not included in the seven-valent conjugate vaccine, it is included in the polysaccharide 23-valent vaccine (PPV23). Individuals eligible for the publicly funded PPV23 may vary by province, but in general, the National Advisory Committee on Immunization (3) recommends PPV23 for the following groups – adults 65 years and older, and individuals five to 64 years of age with chronic cardiorespiratory disease, cirrhosis, alcoholism, chronic renal disease, nephritic syndrome, diabetes mellitus, chronic cerebrospinal fluid leak, sickle cell disease, functional or anatomical asplenia, HIV infection and other conditions associated with immunosuppression. Given the history of alcohol abuse in the 51-year-old woman, the present case represents a missed opportunity for vaccination. Individuals in this high-risk group are difficult to reach for routine immunization programs. We have thus identified a fatal case of S pneumoniae serotype 5 representing a group of people whose risk for disease also decreases their chances of accessing vaccination. Additional approaches to increasing PPV23 immunization coverage in this high-risk, hard-to-access group need to be considered.

CONCLUSION

The present case highlights the difficulty in early diagnosis of NF due to the subtle signs at illness onset and the absence of leukocytosis. The use of oral anti-inflammatories commonly prescribed for noninfectious arthritides may contribute to the severity of infection or mask the symptoms. While PPV23 has limited efficacy against prevention of invasive disease in people with diabetes and alcoholism (17), the final outcome might have been altered if this individual had been immunized. Finally, the emergence of S pneumoniae serotype 5 in Canada may be accompanied by severe disease presentations in individuals at high risk of pneumococcal infections.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Dr Susan Wootton for a review of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Pneumococcal infections. In: Atkinson W, Hamborsky J, McIntyre L, Wolfe S, editors. Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases. 9th edn. Washington: Public Health Foundation; 2006. pp. 255–68. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Academy of Pediatrics. Pneumococcal infections. In: Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Long SS, McMillan JA, editors. Red Book: 2006 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 27th edn. Ilinois: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2006. pp. 525–37. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Public Works and Government Services Canada. Pneumococcal vaccine. Canadian Immunization Guide. 7th edn. Ottawa: Public Works and Government Services Canada; 2006. pp. 271–6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tamayo M, Sá-Leão R, Santos Sanches I, Castañeda E, de Lencastre H. Dissemination of a chloramphenicol- and tetracycline-resistant but penicillin-susceptible invasive clone of serotype 5 Streptococcus pneumoniae in Colombia. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2337–42. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.7.2337-2342.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kellner J, Hastie L, Hui S, et al. Outbreaks of serotype 5 and serotype 8 invasive pneumococcal disease in Calgary. Alberta; Canada: < http://www.promedmail.org> (Version current at December 12, 2007) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romney M, Hull M, Gustafson R, Daly P, Patrick D, David S. Outbreak of serotype 5 pneumococcal disease in Vancouver. British Columbia; Canada: < http://www.promedmail.org> (Version current at December 12, 2007) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaudry W, Talling D. Invasive pneumococcal infection in First Nations children in northern Alberta. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2002;28:165–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ballon-Landa GR, Gherardi G, Beall B, Krosner S, Nizet V. Necrotizing fasciitis due to penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae: Case report and review of the literature. J Infect. 2001;42:272–7. doi: 10.1053/jinf.2000.0801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ben M’Rad M, Brun-Buisson C. A case of necrotizing fasciitis due to Streptococcus pneumoniae following topical administration of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:775–6. doi: 10.1086/342323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choudhri SH, Brownstone R, Hashem F, Magro CM, Crowson AN. A case of necrotizing fasciitis due to Streptococcus pneumoniae. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:128–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb02506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frick S, Cerny A. Necrotizing fasciitis due to Streptococcus pneumoniae after intramuscular injection of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: Report of 2 cases and review. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:740–4. doi: 10.1086/322592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Imhof A, Maggiorini M, Zbinden R, Walter RB. Fatal necrotizing fasciitis due to Streptococcus pneumoniae after renal transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18:195–7. doi: 10.1093/ndt/18.1.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isik A, Koca SS. Necrotizing fasciitis resulting from Streptococcus pneumoniae in recently diagnosed systemic lupus erythematosus case: A case report. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:999–1001. doi: 10.1007/s10067-006-0234-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwak EJ, McClure J, McGeer A, Lee BC. Exploring the pathogenesis of necrotizing fasciitis due to Streptococcus pneumoniae. Scand J Infect Dis. 2002;34:639–44. doi: 10.1080/00365540210147985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prakash PK, Biswas M, ElBourit K, Braithwaite PA, Hanna FW. Pneumococcal necrotizing fasciitis in a patient with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2003;20:899–903. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.00984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stevens DL. Could nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) enhance the progression of bacterial infections to toxic shock syndrome? Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:977–80. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.4.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benin AL, O’Brien KL, Watt JP, et al. Effectiveness of the 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine against invasive pneumococcal disease in Navajo adults. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:81–9. doi: 10.1086/375782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]