Abstract

Cladophialophora is a genus of black yeast-like fungi comprising a number of clinically highly significant species in addition to environmental taxa. The genus has previously been characterized by branched chains of ellipsoidal to fusiform conidia. However, this character was shown to have evolved several times independently in the order Chaetothyriales. On the basis of a multigene phylogeny (nucLSU, nucSSU, RPB1), most of the species of Cladophialophora (including its generic type C. carrionii) belong to a monophyletic group comprising two main clades (carrionii- and bantiana-clades). The genus includes species causing chromoblastomycosis and other skin infections, as well as disseminated and cerebral infections, often in immunocompetent individuals. In the present study, multilocus phylogenetic analyses were combined to a morphological study to characterize phenetically similar Cladophialophora strains. Sequences of the ITS region, partial Translation Elongation Factor 1-α and β-Tubulin genes were analysed for a set of 48 strains. Four novel species were discovered, originating from soft drinks, alkylbenzene-polluted soil, and infected patients. Membership of the both carrionii and bantiana clades might be indicative of potential virulence to humans.

Keywords: Biodiversity, bioremediation, Cladophialophora, chromoblastomycosis, disseminated infection, MLST, mycetoma

INTRODUCTION

Cladophialophora is a genus of black yeast-like fungi which are remarkably frequently encountered in human infections, ranging from mild cutaneous lesions to fatal encephalitis. The genus is morphologically characterized by one-celled, ellipsoidal to fusiform, dry conidia arising through blastic, acropetal conidiogenesis, and arranged in branched chains. The chains are usually coherent and conidial scars are nearly unpigmented (Borelli 1980, Ho et al. 1999, de Hoog et al. 2000). The genus was initially erected to accommodate species exhibiting Phialophora-like conidiogenous cells in addition to conidial chains (Borelli 1980) but thus far this feature is limited to the species C. carrionii. Teleomorphs have not been found, but judging from SSU rDNA phylogeny data, these are predicted to belong to the ascomycete genus Capronia, a member of the order Chaetothyriales (Haase et al. 1999).

The type species of Cladophialophora, C. carrionii, is an agent of chromoblastomycosis, a cutaneous and subcutaneous disease histologically characterized by muriform cells in skin tissue. Muriform cells represent the invasive form of fungi causing chromoblastomycosis (Mendoza et al. 1993). Infections are supposed to originate by traumatic implantation of fungal elements into the skin and are chronic, slowly progressive and localised. Tissue proliferation usually occurs around the area of inoculation, producing crusted, verrucose, wart-like lesions. The genus has been expanded to encompass several other clinically significant species, including the neurotropic fungi C. bantiana and C. modesta causing brain infections (Horré & de Hoog 1999), C. devriesii and C. arxii causing disseminated disease (de Hoog et al. 2000) and C. boppii, C. emmonsii and C. saturnica causing cutaneous infections (de Hoog et al. 2007, Badali et al. 2008).

Based on molecular data, anamorphs morphologically similar to Cladophialophora have been found in other groups of ascomycetes, particularly in the Dothideales / Capnodiales (e.g., Pseudocladosporium, Fusicladium; Crous et al. 2007). Distinction between chaetothyrialean and dothidealean / capnodialean anamorphs is now also supported by their teleomorphs. Braun & Feiler (1995) reclassified the dothidealean species Venturia hanliniana (formerly Capronia hanliniana) as the teleomorph of Fusicladium brevicatenatum (formerly Cladophialophora brevicatenata). Further distinction between Chaetothyriales and Dothideales / Capnodiales lies in their ecology, with recurrent human opportunists being restricted to the Chaetothyriales. Braun (1998), summarizing numerous statements in earlier literature, separated Cladophialophora with Capronia teleomorphs (Herpotrichiellaceae, Chaetothyriales mostly as opportunistic or pathogens), from the predominantly saprobic or plant associated isolates in the Dothideomycetes.

Some species attributed to Cladophialophora may be found in association with living plants. De Hoog et al. (2007) reported a cactus endophyte, Cladophialophora yegresii, as the nearest neighbour of C. carrionii, which is a major agent of human chromoblastomycosis. The latter fungus was believed to grow on debris of tannin-rich cactus spines, which were also supposed to be the vehicle of introduction into the human body. Crous et al. (2007) described several host-specific plant pathogens associated with the Chaetothyriales. Cladophialophora hostae caused spots on living leaves of Hosta plantaginea, C. proteae was a pathogen of Protea cynaroides, and C. scillae caused leaf spots on Scilla peruviana. Finally, Davey & Currah (2007) described Cladophialophora minutissima from mosses collected at boreal and montane sites in central Alberta, Canada. Within the Chaetothyriales, most of these plant-associated species are found at relatively large phylogenetic distance from the main clade of Cladophialophora comprising most of the opportunistic species.

The core of the genus Cladophialophora does comprise a number of environmental saprobes. Cladophialophora minourae and C. chaetospira occur in plant litter. Badali et al. (2008) described C. saturnica from plant debris in the environment, but the species was also found causing an interdigital infection in a Brazilian child with HIV infection. The species C. australiensis and C. potulentorum were found in soft drinks (Crous et al. 2007). If environmental species are able to provoke opportunistic infections, the question arises whether members of Chaetothyriales isolated from food products might imply a health risk. Understanding of the phylogeny and ecology of Cladophialophora is therefore essential. Many review articles incorrectly mention that black yeast-like fungi are commonly found on decomposing plant debris and in soil. In fact, Chaetothyrialean members are difficult to isolate from the environment as they seem to have quite specific, hitherto undiscovered ecological niches (Satow et al. 2008, Vicente et al. 2008). For their isolation, selective methods are required, e.g. by the use of high temperatures (Sudhadham et al. 2008), a mouse vector (Gezuele et al. 1972, Dixon et al. 1980), alkyl benzenes (Prenafeta-Boldú et al. 2006) or isolation via mineral oil (Satow et al. 2008, Vicente et al. 2001, 2008). An association with assimilation of toxic monoaromatic compounds has been hypothesised. Black yeasts and their filamentous relatives in the Chaetothyriales are potent degraders of monoaromatic compounds and tend to accumulate in industrial biofilters (Cox et al. 1997, Prenafeta-Boldú et al. 2001, de Hoog et al. 2006). This might be a clue to dissecting their dual behavior as rare environmental oligotrophs as well as invaders of human tissue containing aromatic neurotransmitters.

The present paper combines ecological information with phylogenetic and taxonomic data, and interprets them in the light of potential health hazards of seemingly saprobic species that may occur in food products. We applied multilocus sequence analysis and phenetic characterization to distinguish novel Cladophialophora species from various sources.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal strains

Strains used in this study were obtained from the Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures (Table 1). Stock cultures were maintained on slants of 2 % malt-extract agar (MEA, Difco) and oatmeal agar (OA, Difco) and incubated at 24 °C for two weeks (Gams et al. 1998). All cultures in this study are maintained in the culture collection of CBS (Utrecht, The Netherlands) and taxonomic information for new species was deposited in MycoBank (www.MycoBank.org).

Table 1.

Isolation data of examined strains.

| Name | CBS | Status | Other reference | GenBank ITS, TUB, EF1α | Source | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cladophialophora carrionii | CBS 114392 | UNEFM 82267 = dH 13261 | EU137267, EU137150, EU137211 | Chromoblastomycosis; leg; female, | Venezuela, Falcon State | |

| CBS 114393 | UNEFM 9801 = dH 13262 | EU137268, EU137151, EU137212 | Chromoblastomycosis; hand; male | Venezuela, Falcon State | ||

| CBS 114396 | UNEFM 2001/1 = dH 13265 | EU137269, EU137152, EU137213 | Chromoblastomycosis; arm; male | Venezuela, Falcon State | ||

| CBS 114398 | UNEFM 2003/1 = dH 13267 | EU137271, EU137154, EU137215 | Chromoblastomycosis; arm; female | Venezuela, Falcon State | ||

| CBS 260.83 | CDC B-1352 = FMC 282 = ATCC 44535 | EU137292, EU137175, EU137234 | Skin lesion in human | Venezuela, Falcon State | ||

| CBS 160.54 | LT | CDC A-835 =(ex-LT of C. carrionii) = ATCC 16264 | EU137266, EU137201, EU137210 | Chromoblastomycosis, human | Venezuela, Falcon State | |

| Cladophialophora yegresii | CBS 114406 | UNEFM SgSR1; dH 13275 | EU137323, EU137208, EU137263 | Stenocereus griseus asymptomatic plant | Venezuela, Falcon State | |

| CBS 114405 | UNEFM SgSr3; dH 13276 | EU137322, EU137209, EU137262 | Stenocereus griseus asymptomatic plant | Venezuela, Falcon State | ||

| CBS 114407 | UNEFM SgSR1; dH 13274 | EU137324, -, U137264 | Stenocereus griseus asymptomatic plant | Venezuela, Falcon State | ||

| Cladophialophora emmonsii | CBS 640.96 | CDC B-3634; NCMH 2248; 4991 | EU103995, -, U140584 | Sub-cutaneous lesion, cat | - | |

| CBS 979.96 | CDC B-3875; NCMH 2247 | EU103996, -, U140583 | Sub-cutaneous lesion right forearm, human | U.S.A., Virginia | ||

| Cladophialophora boppii | CBS 126.86 | FMC 292; dH 15357 | EU103997, -, U140596 | Skin lesion, on limb, male | Brazil | |

| CBS 110029 | det M-41/2001 56893; dH 12362 | EU103998, -, U140597 | Scales of face, male | Netherlands, Dordrecht | ||

| Cladophialophora bantiana | CBS 173.52 | T | CBS 100433 | EU103989, -, U140585 | Brain abscess, male | U.S.A. |

| CBS 444.96 | - | EU103994, -, U140591 | Disseminated infection, dog | South Africa, Pretoria, Onderstepoort | ||

| CBS 678.79 | CDC B-3658; NCMH 2249; NIH B-3839 | EU103992, -, U140592 | Skin lesion, cat | U.S.A., Bethesda | ||

| CBS 648.96 | UAMH 3830 | EU103993, -, U140587 | Liver, dog | Barbados | ||

| Cladophialophora saturnica | CBS 109628 | dH 12333; IHM 1727 | EU103983, -, U140601 | Dead tree | Uruguay, Isla Grande del Queguay | |

| CBS 109630 | dH 12335; IHM 1733 | FJ385270, -, - | Trunk, cut tree | Uruguay, Isla Grande del Queguay | ||

| CBS 118724 | T | 157D; dH 12939 | EU103984, -, EU140602 | Interdigital toe lesion, child | Brazil, Paraná, Curitiba | |

| CBS 102230 | dH 11591; 4IIBPIRA | AY857508, -, EU140600 | Litter, vegetable cover/soil | Brazil, Paraná, Curitiba | ||

| CBS 114326 | ATCC 200384 | AY857507, -, EU140603 | Toluene biofilter | Netherlands, Wageningen | ||

| Cladophialophora devriesii | CBS 147.84 | T | ATCC 56280; CDC 82-030890 | EU103985, -, EU140595 | Disseminated infection, male | U.S.A., Grand Cayman Island |

| CBS 118720 | ISO 13F | FJ385275, -, - | Litter, vegetable cover/soil | Brazil, Paraná, Curitiba | ||

| Cladophialophora arxii | CBS 306.94 | T | EU103986, -, EU140593 | Tracheal abscess, male | Germany | |

| Cladophialophora minourae | CBS 987.96 | IFM 4701; UAMH 5022 | EU103988, -, EU140599 | Rotting wood | Japan, Yachimata, Chiba | |

| CBS 556.83 | ATCC 52853; IMI 298056 | AY251087, -, EU140598 | Decaying wood | Japan, Shiroi | ||

| Cladophialophora immunda | CBS 110551 | dH15250 | FJ385274, EU137207, EU137261 | Gasolin-station soil | Netherlands, Apeldoom | |

| CBS 109797 | dH 11474 | FJ385271, EU137206, EU137260 | Biofilter inoculated with soil | Germany, Kaiserslautern | ||

| CBS 834.96 | T | CDCB-5680; de H.10680 | EU137318, EU137203, EU137257 | Sub-cutaneous phaeohyphomycosis, male | U.S.A., Georgia, Atlanta | |

| CBS 102227 | dH 11588 | FJ385269, -, EU137259 | Syagrum romanzoffianum, stem | Brazil, Paraná, Colombo | ||

| CBS 102237 | dH 11601 | FJ385272, EU137205, EU137285 | Decaying cover vegetable | Brazil, Paraná, Sarandi | ||

| Cladophialophora samoënsis | CBS 259.83 | T | CDC B-3253; dH 15637 | EU137291, EU137174, EU137233 | Chromoblastomycosis skin lesion, male | U.S.A., Samoa |

| Cladophialophora subtilis | CBS 122642 | T | dH 14614 | FJ385273, -, - | Ice tea | Netherlands, Utrecht |

| Cladophialophora mycetomatis | CBS 454.82 | dH 15898 | EU137293, EU137176, EU137235 | Culture contaminant | Netherlands | |

| CBS 122637 | T | dH 18909 | FJ385276, -, - | Eumycetoma, male | Mexico, Jicaltepec | |

| Fonsecaea monophora | CBS 289.93 | T | dH 15691 | AY366925, EU938554, - | Lymphnode, aspiration-biopsy | Netherlands (zoo) |

| CBS 102238 | dH 11602, 1PLE | AY366927, EU938546, - | Soil | Brazil | ||

| CBS 102248 | dH 11613 | AY366926, EU938550, - | Chromoblastomycosis, male | Brazil | ||

| Fonsecaea pedrosoi | CBS 271.37 | T | ATCC 18658; IMI 134458; dH 15659 | AY366914, EU938559, - | Chromoblastomycosis, male | South America |

| CBS 272.37 | dH 15661 | AY366917, -, - | Chromoblastomycosis, male | - | ||

| Cladophialophora australiensis | CBS 112793 | CPC 1377 | EU035402, -, - | Sports drink | Australia | |

| Cladophialophora chaetospira | CBS 491.70 | - | EU035405, -, - | Roots of Picea abies | Denmark | |

| Cladophialophora potulenturum | CBS 112222 | CPC 1376; FRR 4946 | EU035409, -, - | Sports drink | Australia | |

| CBS 114772 | CPC 1375; FRR 4947 | EU035410, -, - | Sports drink | Australia |

Abbrevations used: ATCC = American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, U.S.A.; CBS = Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Utrecht, The Netherlands; DH = G.S. de Hoog private collection; IFM = Research Institute for Pathogenic Fungi, Chiba, Japan; IHM = Laboratory of Mycology, Faculty of Medicine, Montevideo Institute of Epidemiology and Hygiene, Montevideo, Uruguay; IMI = International Mycological Institute, London, U.K.; IWW = Rheinisch Westfählisches Institut für Wasserforschung, Mülheim an der Ruhr, Germany; GHP = G. Haase private collection; MUCL = Mycotheque de l'Université de Louvain, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium; NCMH = North Carolina Memorial Hospital, Chapel Hill, U.S.A.; RKI = Robert Koch Institute, Berlin, Germany; UAMH = Microfungus Herbarium and Collection, Edmonton, Canada; UTHSC = Fungus Testing Laboratory, Department of Pathology, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, U.S.A.; UTMB = Medical Mycology Research Center, Galveston, U.S.A.; UNEFM = Universidade Nacional Experimental Francisco de Miranda, Coro, Falcon, Venezuela. T = ex-type culture; LT = ex-lectotype culture;

DNA extraction

The fungal mycelia were grown on 2 % (MEA) plates for 2 wks at 24 °C (Gams et al. 1998). A sterile blade was used to scrape off the mycelium from the surface of the plate. DNA was extracted using an Ultra Clean Microbial DNA Isolation Kit (Mobio, Carlsbad, CA 92010, U.S.A.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA extracts were stored at –20 °C prior to use.

Amplification and sequencing

Four genes were amplified: the internal transcribed spacer region (ITS), the translation elongation factor 1 alpha (EF1-α), the partial beta tubulin gene (TUB), and the small subunit of the nuclear ribosomal RNA gene (nucSSU). The primers used for amplification and sequencing are shown in Table 2. PCR reactions were performed on a Gene Amp PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in 50 μL volumes containing 25 ng of template DNA, 5 μL reaction buffer (0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.5 M KCl, 15 mM MgCl2, 0.1 % gelatine, 1 % Triton X-100), 0.2 mM of each dNTP and 2.0 U Taq DNA polymerase (ITK Diagnostics, Leiden, The Netherlands). Amplification of ITS and nucSSU was performed with cycles of 2 min at 94 °C for primary denaturation, followed by 35 cycles at 94 °C (45 s), 52 °C (30 s) and 72 °C (120 s), with a final 7 min extension step at 72 °C. Annealing temperatures used to amplify EF1α and TUB genes were 55 and 58 °C, respectively. Amplicons were purified using GFX PCR DNA and gel band purification kit (GE Healthcare, Ltd., Buckinghamshire U.K.). Sequencing was performed as follows: 95 °C for 1 min, followed by 30 cycles consisting of 95 °C for 10 s, 50 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 2 min. Reactions were purified with Sephadex G-50 fine (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences AB, Uppsala, Sweden) and sequencing was done on an ABI 3730XL automatic sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, U.S.A.). Sequence data obtained in this study were adjusted using the SeqMan of Lasergene software (DNAStar Inc., Madison, Wisconsin, U.S.A.).

Table. 2.

Primer sequences for PCR amplification and sequencing.

| Gene | PCR primers | Sequencing primers | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| ITS rDNA | V9Ga, LS266b | ITS1c, ITS4c | a de Hoog et al. (1998) |

| b Masclaux et al. (1995) | |||

| c White et al. (1990) | |||

| TUB | Bt2a, Bt2b | Bt2a, Bt2b | Glass & Donaldson (1995) |

| EF1-α | EF1-728F, EF1-986R | EF1-728F, EF1-986R | Carbone & Kohn (1999) |

| SSU rDNA | NS1a, NS24b | (BF83, Oli1, Oli9, BF951, BF963, BF1438, Oli3, BF1419)c | a White et al. (1990) |

| b Gargas & Taylor (1992) | |||

| c de Hoog et al. (2005) |

Alignment and phylogenetic reconstruction

Phylogenetic analyses were carried out on three different datasets. The first dataset included a taxon sampling representative of the order Chaetothyriales (94 taxa) and the three genes nucLSU, nucSSU and RPB1. This dataset was used in order to assess the phylogenetic placement of diverse species of Cladophialophora within the Chaetothyriales. For this first analysis, sequences of nucSSU obtained from investigated strains of Cladophialophora were added to an existing dataset representing the Chaetothyriales (Gueidan et al. 2008). Alignments were done manually for each gene using MacClade 4.08 (Maddison & Maddison 2003) with the help of amino acid sequences for protein coding loci. Ambiguous regions and introns were excluded from the alignments. The program RAxML-VI-HPC v.7.0.0 (Stamatakis et al. 2008), as implemented on the Cipres portal v.1.10, was used for the tree search and the bootstrap analysis (GTRMIX model of molecular evolution and 500 bootstrap replicates). Bootstrap values equal or greater than 70 % were considered significant (Hillis & Bull 1993).

The second and third datasets focused on two main monophyletic clades nested within the core group of Cladophialophora (Clade I and Clade II, Fig. 1). They included three genes, ITS, EF1α and TUB. The goal of these two analyses was to assess the delimitation of species of Cladophialophora. The second dataset (Clade I or carrionii-clade) comprised 15 taxa, and the third dataset (Clade II or bantiana-clade) 33 taxa. Phylogenetic reconstructions and bootstrap values were first obtained for each locus separately using RAxML (as described above). The congruence between loci was assessed using a 70 % reciprocal bootstrap criterion (Mason-Gamer & Kellogg 1996). The loci were then combined and analysed using RAxML (as described above). The phylogenetic trees were edited using Tree View v.1.6.6.

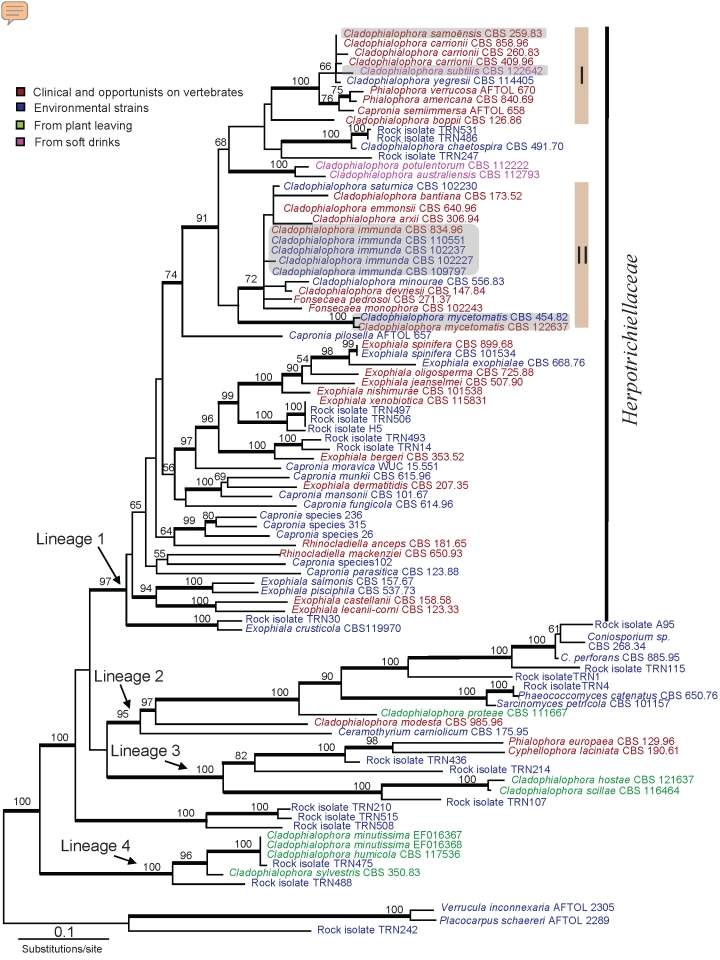

Fig. 1.

Phylogeny obtained from a ML analysis of three combined loci (SSU, LSU and RPB1) using RAxML. Bootstrap support values were estimated based on 500 replicates, and are shown above the branches (thick branch for values ≥ 70 %). The tree was rooted using Verrucula inconnexaria, Placocarpus schaereri and the rock isolate TRN242. New species are highlighted with grey boxes.

Morphological identification and cultural characterisation

Strains were cultured on 2 % MEA and OA and incubated at 24 °C in the dark for two wks (Gams et al. 1998). Identification was based primarily on macroscopic and microscopic morphology. Microscopical observations were based on slide culture techniques using potato dextrose agar (PDA) or OA because these media readily induce sporulation and suppress growth of aerial hyphae (de Hoog et al. 2000). Mounts of two-wk-old slide cultures were made in lactic acid or lactophenol cotton blue and light micrographs were taken using Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope with a Nikon digital sight DS-Fi1 camera.

Physiology

Cardinal growth temperatures of strains were determined on 2 % MEA (Difco) (Crous et al. 1996). Plates were incubated in the dark for two wks at temperatures of 6–36 °C at intervals of 3 °C; in addition, growth at 40 °C was recorded. Experiments consisted of three simultaneous replicates for each isolate; the entire procedure was repeated once.

Muriform cells

All strains were tested for the production of muriform cells, i.e., the meristematic tissue form of agents of human chromoblastomycosis. Strains were incubated at 25 and 37 °C for one wk in a defined medium with low pH containing 0.1 mM/L calcium chloride. The basal medium was prepared by adding the following components to 1 L deionized distilled water: 30 g glucose, 3 g NaNO3, 0.01 g FeSO4·7H2O, 0.265 g NH4Cl, 0.003 g thiamin and 1 mM CaCl2; the pH was adjusted to 2.5 with HCl for all experiments (Mendoza et al. 1993).

RESULTS

Phylogeny

Chaetothyriales dataset

Fig. 1 shows that, in the order Chaetothyriales, species of Cladophialophora belong to at least four different lineages: one lineage corresponding to the family Herpotrichiellaceae (lineage 1, Fig. 1), and three basal lineages including mostly rock-inhabiting strains (lineages 2, 3 and 4, Fig. 1). Most of the human-opportunistic species (including the most virulent ones) belong to two well-supported clades within the Herpotrichiellaceae. Clade I (carrionii-clade, Fig. 1, 2) includes the pathogenic Cladophialophora species C. carrionii and C. boppii, as well as two pathogenic species of Phialophora (P. verrucosa and P. americana). Clade II (bantiana-clade, Fig. 1, 3) includes the pathogenic species C. bantiana, C. arxii, C. immunda, C. devriesii, C. saturnica, C. emmonsii, and C. mycetomatis, as well as the pathogenic genus Fonsecaea (F. pedrosoi and F. monophora). All the plant associated species of Cladophialophora belong to lineages 2, 3 and 4. Lineage 2 includes rock-inhabiting strains and the opportunistic pathogen C. modesta. Lineage 3 includes rock-inhabiting strains, the two opportunistic pathogens P. europaea, and C. laciniata, and three plant associated species of Cladophialophora (C. proteae, C. hostae, and C. scillae). Lineage 4 includes exclusively rock-inhabiting strains and plant leaving strains (C. minutissima, C. humicola, and C. sylvestris).

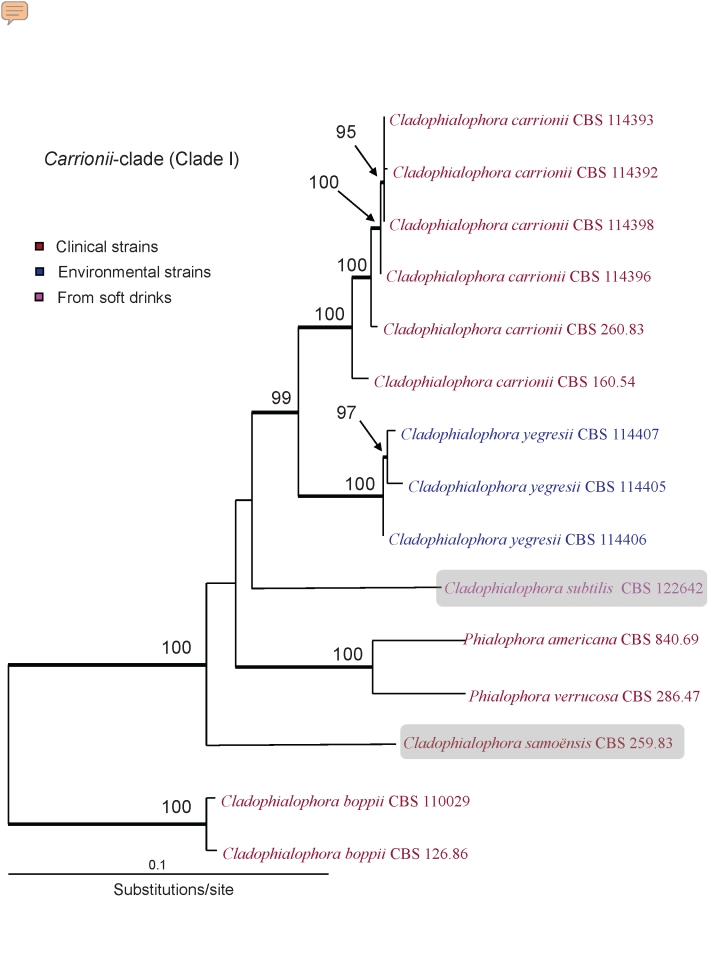

Fig. 2.

Phylogeny of Clade I obtained from a ML analysis of three combined loci (ITS rDNA, EF1-α and TUB) using RAxML. Bootstrap support values were estimated based on 500 replicates, and are shown above the branches (thick branch for values ≥ 70 %). New species are highlighted using with grey boxes. Cladophialophora boppii (CBS 126.86 and CBS 110029) were taken as outgroup.

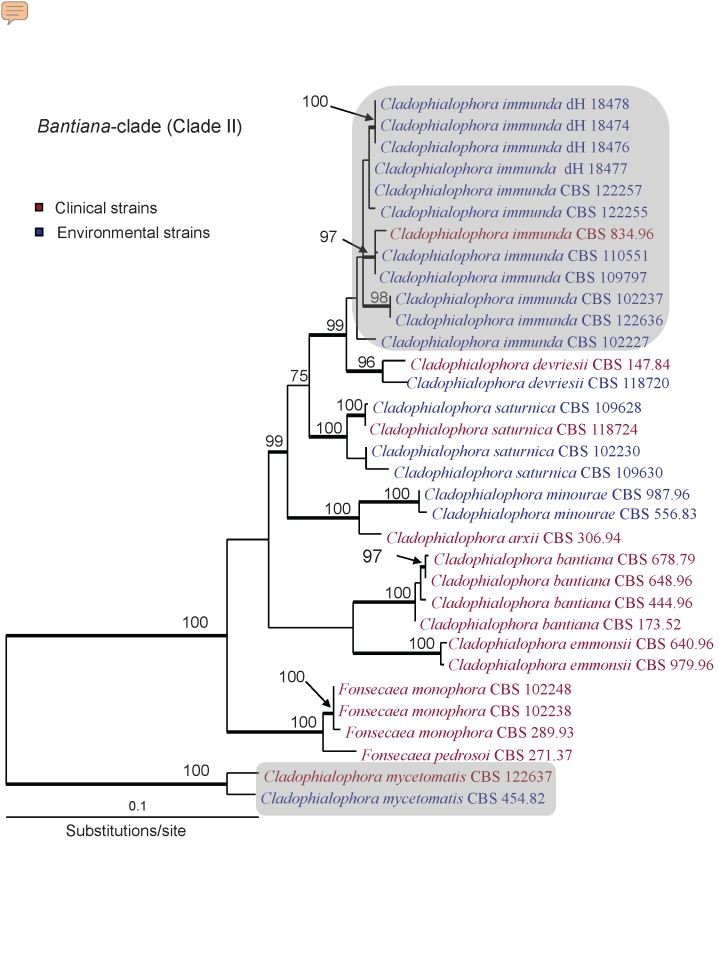

Fig. 3.

Phylogeny of Clade II obtained from a ML analysis of three combined loci (ITS rDNA, EF1-α and TUB) using RAxML. Bootstrap support values were estimated based on 500 replicates, and are shown above the branches (thick branch for values ≥ 70 %). New species are highlighted using with grey boxes. The tree was rooted with two strains of Cladophialophora mycetomatis (CBS 454.82 and CBS 122637).

Carrionii-clade dataset

Phylogenetic reconstructions of Clade I (carrionii-clade; Fig. 2) were first carried out for each gene separately (ITS: 542 characters, EF1-α: 117 characters, TUB: 402 characters). Topological conflicts were detected for all genes within both C. carrionii and C. yegresii. This incongruence involving only below species-level relationships, and therefore – in agreement with the genealogical recognition species concept (Taylor et al. 2000) –, the conflicts were ignored and the three loci were combined. In this combined analysis, C. boppii, an agent of cutaneous infection, was taken as an out-group for clade I (Fig. 2). The combined analysis shows that both the pathogenic species C. carrionii (represented by 6 strains) and the environmental species C. yegresii (represented by 3 strains) are monophyletic and well supported (100 % bootstrap, Fig. 2). The two species of Phialophora (P. verrucosa and P. americana) are sister taxa (100 % bootstrap, Fig. 2), and are nested among species of Cladophialophora. Two newly investigated strains (CBS 122642, isolated from soft drink; CBS 259.83, isolated from a patient with chromoblastomycosis) are shown to be phylogenetically distinct from other members of Clade I, and are described below as new species (C. samoënsis and C. subtilis).

Bantiana-clade dataset

Phylogenetic reconstructions of Clade II (bantiana-clade, Fig. 3) were first carried out for each gene separately (ITS: 495 characters, EF1-α: 133 characters, and TUB: 355 characters). As topological incongruence was detected only within the species C. saturnica (relationships obtained with ITS differed from relationships obtained with EF1-α or TUB), the loci were combined. The resulting tree was rooted using C. mycetomatis, a species newly described here. A phylogenetic analysis at larger scale (Fig. 1) shows that this taxon is phylogenetically distinct from other species of Cladophialophora, and sister to all the other members of the bantiana-clade. The three species C. immunda, C. devriesii and C. saturnica all form monophyletic clades including both clinical and environmental strains. For C. immunda, strains from different geographical areas and ecological preferences all cluster together. The environmental species C. minourae is sister to the pathogenic species C. arxii. The truly pathogenic species C. bantiana is sister to C. emmonsii, although with no support. Finally, the genus Fonsecaea forms a well-supported monophyletic group nested within this clade of Cladophialophora.

Physiology

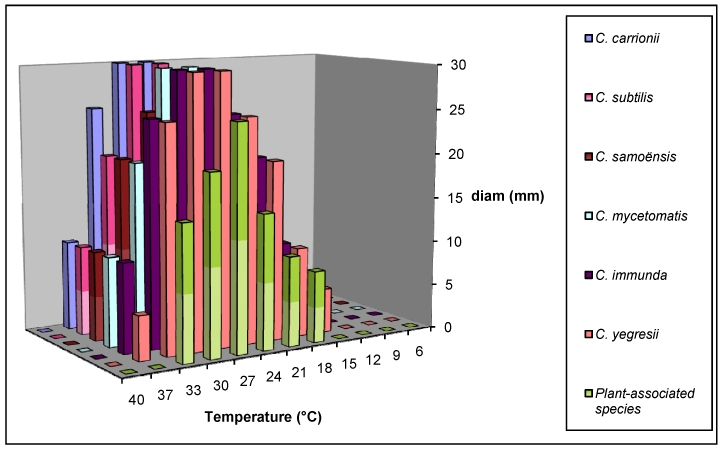

The cardinal growth temperature test showed that all cultures obtained in this study had their optimal development at 27-30 °C, with growth abilities ranging between 9-37 °C. No growth was observed at 40 °C. For C. samoënsis, C. immunda and C. mycetomatis, the optimum growth temperature on MEA and PDA was 27 °C, with minimum and maximum of 15 and 37 °C, respectively. For all the other species, growth temperatures were identical except for the minimum temperature, which was 12 °C in C. subtilis. However, neither plant associated species nor strains isolated from sport drink nor apple juice (C. australiensis and C. potulentorum) had the ability to grow at 37 and 40 ° C (Fig. 4). Growth characteristics were studied at low pH after addition of 0.1 mM CaCl2 to the basal medium, inducing conversion of hyphae of Cladophialophora species into muriform cells when incubated at 25–37 °C (Table 3). Cladophialophora subtilis developed extensive mycelia and produced muriform cells at 25 °C after one wk incubation (Fig. 5). Hyphae were generally attached to these muriform cells in either terminal or intercalary positions (Fig. 5). However, no muriform cells were observed under the same conditions at 25 °C in other species (C. immunda, C. mycetomatis and C. samoënsis). Hyphae of C. subtilis, C. immunda and C. samoënsis converted to large numbers of muriform cells when incubated in the same conditions at 37 °C. Moreover, muriform cells were not observed for plant-associated species of Cladophialophora and for C. mycetomatis and C. yegresii neither at 25 nor at 37 °C (Table 3).

Fig. 4.

Colony diameters of novel Cladophialophora species at different temperatures ranging from 6 to 40 °C, measured after two wks on 2 % MEA.

Table. 3.

Effect of calcium and temperature on production of muriform cells under the acidic conditions in basal medium for 13 species of Cladophialophora.

| Cladophialophora species | Muriform Cells at 25 °C, 0.1 mM Ca2+ and pH 2.5 | Muriform Cells at 37 °C, 0.1 mM Ca2+ and pH 2.5 |

|---|---|---|

| C. carrionii | + | ++ |

| C. samoënsis | - | + |

| C. subtilis | + | +++ |

| C. mycetomatis | - | - |

| C. immunda | - | + |

| C. australiensis | - | - |

| C. potulentorum | - | - |

| C. yegresii | - | - |

| C. sylvestris | - | - |

| C. humicola | - | - |

| C. hostae | - | - |

| C. proteae | - | - |

| C. scillae | - | - |

No production of muriform cells is indicated by -, low production of small muriform cells by +, moderate production of large muriform cells by ++, and large production of large muriform cells by +++.

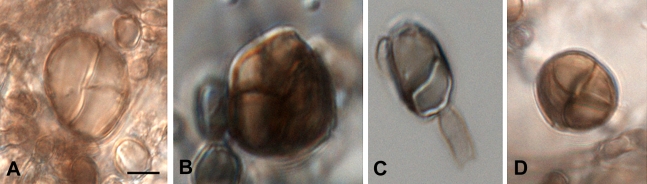

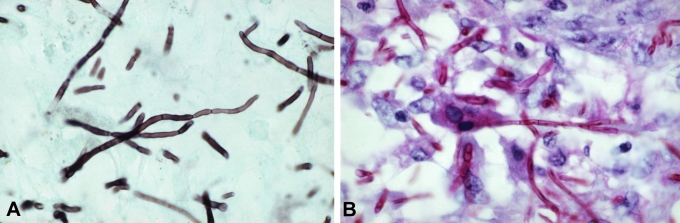

Fig. 5.

Morphology of muriform cells in three species of Cladophialophora. A–B. Cladophialophora subtilis. C. Cladophialophora immunda. D. Cladophialophora carrionii. Scale bar = 10 μm.

Taxonomy of Cladophialophora

Cladophialophora carrionii (Trejos) de Hoog, Kwon-Chung & McGinnis, J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 33: 345 (1995).

≡ Cladosporium carrionii Trejos, Revista de Biologia Tropicale, Valparaiso 2: 106 (1954)

= Cladophialophora ajelloi Borelli, Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Mycoses: 335 (1980)

Type: Trejos 27 (CBS H-18465, lectotype designated here; CBS 160.54 = ATCC 16264 = CDC A-835 = MUCL 40053, ex-type).

Trejos (1954) introduced Cladophialophora carrionii but he did not indicate a holotype. For this reason, the isolate Trejos 27 = Emmons 8619 = CBS 160.54, the first strain mentioned by Trejos (1954), is selected here as lectotype for C. carrionii. The ex-type strain of Cladophialophora ajelloi, CBS 260.83, proved to be indistinguishable from C. carrionii based on both morphology and molecular data. This former species was also known to be able to produce phialides in addition to catenate conidia (Honbo et al. 1984). Cladophialophora ajelloi is here proposed as a taxonomic synonym of C. carrionii.

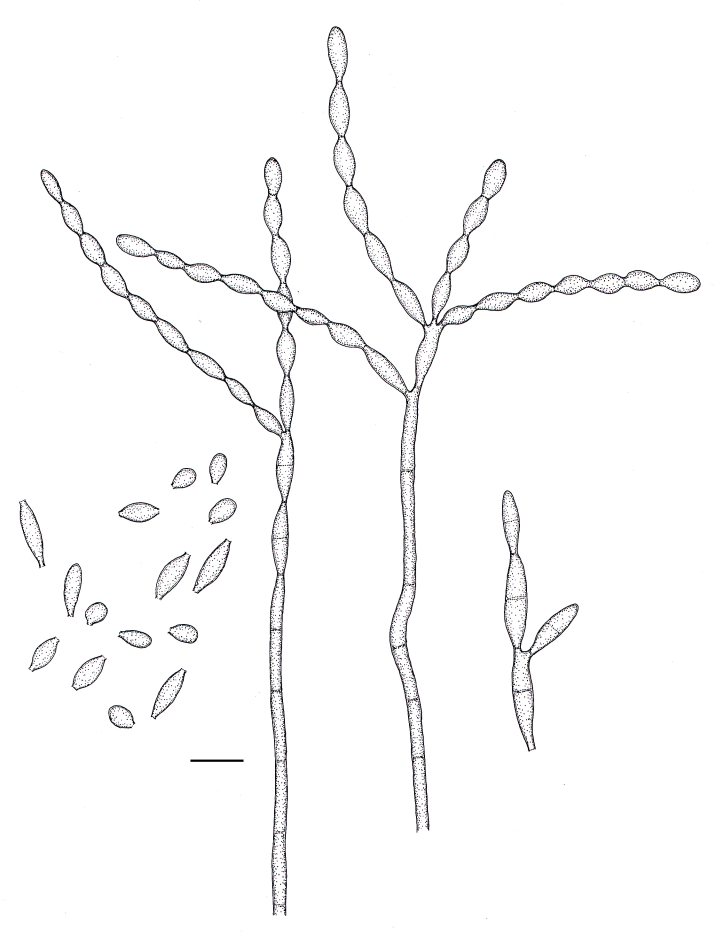

Cladophialophora samoënsis Badali, de Hoog & Padhye, sp. nov. MycoBank MB511809. Fig. 6, 7.

Fig. 6.

Cladophialophora samoënsis (CBS 259.83). A. Conidiophore. B–E. Conidial chains with ramoconidia and conidia. F. Conidiogenous loci (arrows). Scale bar = 10 μm.

Fig. 7.

Microscopic morphology of C. samoënsis (CBS 259.83). Branched conidial chains with ramoconidia and conidia. Conidiophores septate, lateral or terminal, with denticles on the stipe and on 0–1-septate ramoconidia. Scale bar = 10 μm.

Etymology: Named after Samoa, the Pacific Island where the species was encountered in a human patient.

Coloniae fere lente crescentes, ad 30 mm diam post 14 dies, olivaceo-virides vel griseae, reversum olivaceo-nigrum. Cellulae gemmantes absentes. Hyphae leves, hyalinae vel pallide brunneae, 2–3 μm latae. Conidiophora semi-macronemata, septata, lateralia vel terminalia; stipites et ramoconidia denticulata. Conidia holoblastica, dilute brunnea, late fusiformia, unicellularia, levia, catenas longas ramosas cohaerentes formantia, cicatricibus dilute brunneis, 3–4 × 2–3 μm. Synanamorphe not visa. Chlamydosporae absentes. Teleomorphe ignota.

Description based on CBS 259.83 at 27 °C on MEA after 2 wks in darkness.

Cultural characteristics: Colonies growing moderately slowly, reaching up to 30 mm diam, olivaceous-green to grey, with a thin, dark, well-defined margin, dry, velvety, darker after 4 wks; reverse olivaceous-black. Cardinal temperatures: minimum 15 °C, optimum 27–30 °C, maximum 37 °C. No growth at 40 °C.

Microscopy: Budding cells absent. Hyphae smooth, hyaline to pale brown, branched, 2–3 μm wide, locally forming hyphal strands and coils. Conidiophores semi-macronematous, septate, lateral or terminal, with denticles on the stipe and on 0–1-septate ramoconidia. Conidia holoblastic pigmented, broadly fusiform, one-celled, pale brown, smooth-walled, forming long, cohering, branched acropetal chains of conidia; conidial scars pale. Conidia 3–4 × 2–3 μm. Synanamorph not seen. Chlamydospores absent. Teleomorph unknown.

Specimen examined: U.S.A., Samoa (Pacific), isolated from human patient with chromoblastomycosis, November 1979 (CBS H-20113, holotypus; CDC B-3253 = CBS 259.83, ex-type).

Notes: This strain (CBS 259.83, from Samoa) was previously identified as C. ajelloi (Goh et al. 1982). In our multigene analysis, it clustered within the carrionii complex (Clade I; Fig. 2), but proved to be consistently different from all described species.

Case Report: According to the description by Goh et al. (1982), a healthy, 43-yr-old male patient had a 5 × 3 cm erythematous, scaling lesion on his arm which was first observed about 3 yr earlier. The patient did not remember the circumstances under which the infection had been acquired. Muriform cells were revealed in superficial dermis and stratum corneum after skin scrapings. Histological examination showed segments of well-differentiated stratified squamous epithelium with moderate keratin production and underlying coarsely fibrillar dermal connective tissue. In this tissue, dense aggregates of chronic inflammatory cells, including lymphocytes, plasma cells and multinucleated foreign bodies (giant cells), were observed. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stained sections characterized dark brown, thick-walled, multiseptate muriform cells, measuring 6–12 μm in diameter, and dividing by fission. The histopathological observations led to the diagnosis of chromoblastomycosis, and the strain was identified as C. ajelloi (Goh et al. 1982). The taxon name C. ajelloi is not available for this taxon, as it was shown here to be a synonym of C. carrionii. Hence Cladophialophora samoënsis is described as a novel agent of chromoblastomycosis. Morphological observation showed branched chains of holoblastic conidia identical to those of Cladophialophora carrionii.

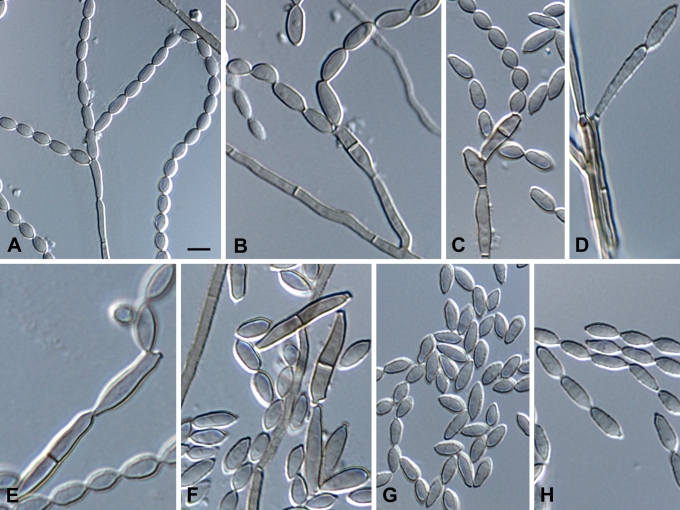

Cladophialophora subtilis Badali & de Hoog, sp. nov. MycoBank MB511842. Figs 8, 11.

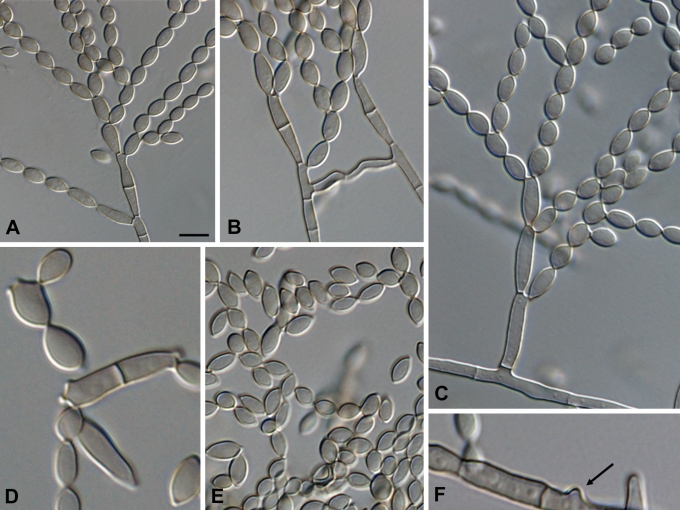

Fig. 8.

Microscopic morphology of C. subtilis (CBS 122642). Fertile hyphae septate, ascending to erect. Conidiophores apically branched, cylindrical to sub-cylindrical Branched conidial chains with ramoconidia and conidia. Scale bar = 10 μm.

Fig. 11.

Cladophialophora subtilis (CBS 122642). A–D. Conidiophores with branched conidial chains and ramoconidia. E. Sympodial conidiogenesis. F–G. Conidiogenous loci (arrows). H. Conidia. Scale bars = 10 μm.

Etymology: Named after thin-walled, conidial structures.

Coloniae fere lente crescentes, ad 30 mm diam post 14 dies, velutinae, olivaceo-virides vel griseae, reversum olivaceo-nigrum. Cellulae gemmantes absentes. Hyphae leves, hyalinae vel pallide brunneae, 2–3 μm latae. Conidiophora micronemata, septata, lateralia vel terminalia; stipites et ramoconidia denticulata. Conidia holoblastica, dilute brunnea, late fusiformia, unicellularia, levia, catenas longas ramosas cohaerentes formantia, cicatricibus dilute brunneis, 5–6 × 2–3 μm. Synanamorphe not visa. Chlamydosporae absentes. Teleomorphe ignota.

Description based on CBS 122642 at 27 °C on MEA after 2 wks in darkness.

Cultural characteristics: Colonies growing slowly, reaching 30 mm diam (10 mm at 37 °C on PDA). Colonies velvety, olivaceous-black, with a wide well defined margin darker than the colony centre, and a compact suede-like to downy surface; reverse olivaceous-black. Cardinal temperatures: minimum 12 °C, optimum 27–30 °C, maximum 37 °C. No growth at 40 °C.

Microscopy: Fertile hyphae septate, ascending to erect, smooth, thin-walled, hyaline to pale olivaceous, guttulate, branched, 2–3 μm wide, forming hyphal strands and hyphal coils. Conidiophores either micronematous, erect, sub-cylindrical, often reduced to a conidiogenous cell, or semi-macronematous, with stalks 60–80 μm long, guttulate, hyaline to pale olivaceous, cylindrical to sub-cylindrical, apically branched, 2.5–3 μm wide. Conidiogenous cells pale brown, slightly darker than conidia, sub-cylindrical to fusiform, with pigmented scars, smooth-walled, proliferating sympodially with 1–3, denticle-like extensions and guttulate. Ramoconidia present. Conidia one-celled, produced in long coherent chains, subhyaline to hyaline, smooth, thin-walled, guttulate; conidia and ramoconidia ellipsoidal to ovoid, 5–6 × 2–3 μm, non-septate. Chlamydospores absent. Teleomorph unknown.

Specimen examined: The Netherlands, Utrecht, isolated from ice tea, December 2004, (CBS H-20114, holotypus; CBS 122642 = dH 14614, ex-type).

Notes: The species is morphologically similar to C. carrionii, an agent of chromoblastomycosis. However, C. subtilis has distinct erect conidiophores which arise at right angles from fertile hyphae; conidiogenous cells are pale brown, slightly darker than conidia, sub-cylindrical to fusiform, with pigmented scars, proliferating sympodially with 1–3, denticle-like extensions.

The species is known from a single strain originating from commercial ice tea. Several Cladophialophora species have been isolated from sugared drinks (C. potulentorum, C. australiensis), while pathogenic Exophiala species also have a preference for sugar-rich surfaces of fruits (Sudhadham et al. 2008). The association of Chaetothyrialean anamorphs with drinks is thus not surprising. The group is also associated with human disorders (de Hoog et al. 2000, Levin et al. 2004). Our species has the ability to grow at 37 °C and produces muriform cells when incubated at 25 and 37 °C at low pH (pH = 2.5). Further studies are required to evaluate its pathogenic ability.

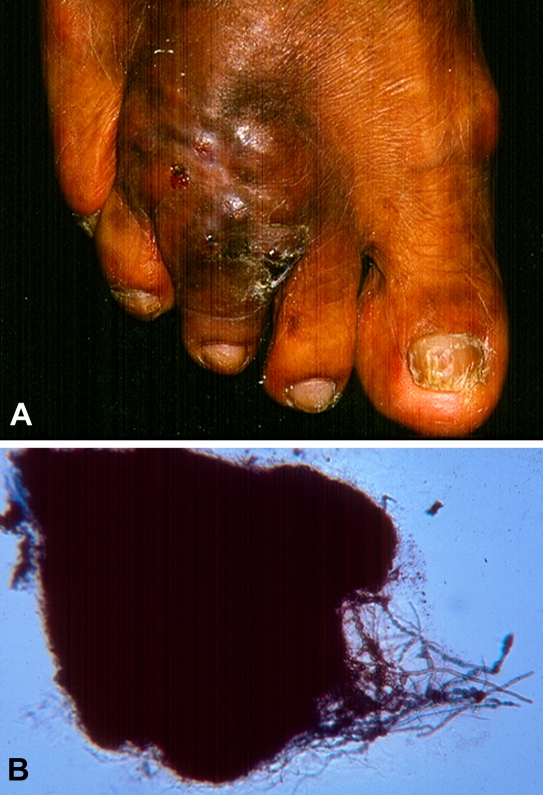

Cladophialophora mycetomatis Badali, de Hoog & Bonifaz, sp. nov. MycoBank MB511843. Figs 9, 12.

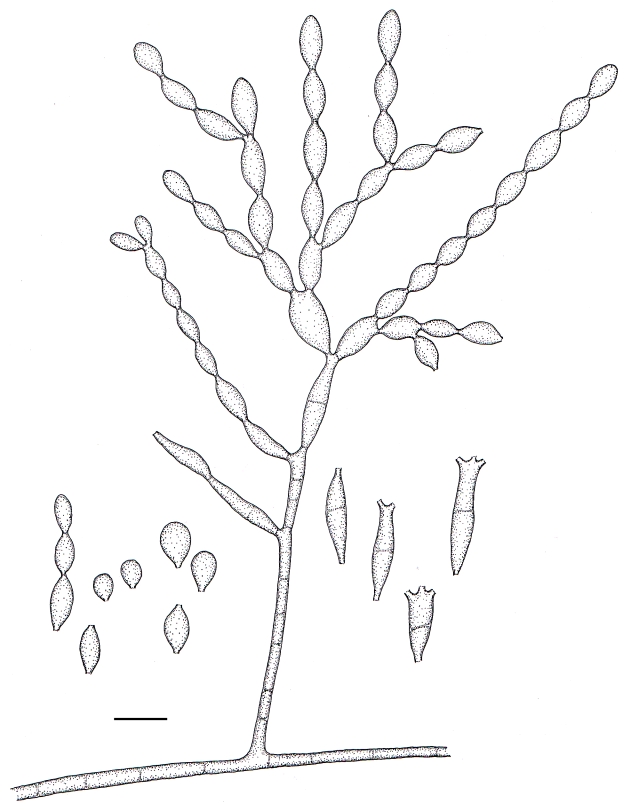

Fig. 9.

Microscopic morphology of C. mycetomatis (CBS 122637 and CBS 454.82). Septate hyphae creeping, ascending to sub-erect. Conidiophores solitary, micronematous, cylindrical, apically branched. Conidia holoblastic, fusiform produced in long chains. Scale bar = 10 μm.

Fig. 12.

Cladophialophora mycetomatis (CBS 122637 and CBS 454.82). A–B. Conidiophores and conidial chains with ramoconidia and conidia. C–D. Cylindrical, septate conidiophores. G. Ellipsoidal to fusiform conidia. Scale bars = 10 μm.

Etymology: Named after the clinical picture mycetoma caused by one of the strains.

Coloniae fere lente crescentes, ad 30 mm diam post 14 dies, velutinae, olivaceo-griseae, reversum olivaceo-nigrum. Cellulae gemmantes absentes. Hyphae leves, hyalinae vel pallide brunneae, 2.5–3 μm latae. Conidiophora solitaria micronemata, dilute brunnea, cylindrica, sursum ramosa, 3.0–3.5 μm lata. Cellulae conidiogenae dilute brunneae, leves, sympodialiter proliferentes. Ramoconidia 0–(1)-septata, cylindrica vel fusiformia, 2.5–4 × 2.5–3 μm. Conidia holoblastica, dilute brunnea, late fusiformia, unicellularia, levia in catenis longis ramosis cohaerentia, cicatricibus dilute brunneis, 2.5–3 × 2–3. Synanamorphe not visa. Chlamydosporae absentes. Teleomorphe ignota.

Description based on CBS 122637 at 27 °C on MEA after 2 wks in darkness.

Cultural characteristics: Colonies moderately expanding, reaching up to 30 mm diam, olivaceous-grey, velvety; reverse olivaceous-black. Cardinal temperatures: minimum 15 °C, optimum 27–30 °C, maximum 37 °C [maximum growth temperature 33 °C; CBS 454.82].

Microscopy: Budding cells absent. Septate hyphae creeping, ascending to sub-erect, smooth-walled, hyaline to pale olivaceous, guttulate, branched, 2.5–3.0 μm wide. Conidiophores solitary, micronematous, pale brown, cylindrical, apically branched, 3.0–3.5 μm wide. Conidiogenous cells pale brown, smooth-walled, sympodially proliferating. Ramoconidia cylindrical to fusiform, 2.5–4.0 × 2.5–3.0 μm. Conidia holoblastic, fusiform produced in long chains; subhyaline to pale olivaceous, guttulate. Chlamydospores absent. Teleomorph unknown.

Specimen examined: Mexico, Jicaltepec, isolated from human patient with mycetoma, 2006 (CBS H-20116, holotypus; CBS 122637, ex-type).

It is remarkable that an environmental strain of C. mycetomatis (CBS 454.82) was isolated by W. Gams as a culture contaminant in the strain of Scytalidium lignicola Pesante (CBS 204.71) from the Netherlands. It was morphologically very similar to C. carrionii but was methyl-α-D-glucoside and melibiose negative and assimilated D-glucosamine and galactitol (de Hoog et al. 1995).

Case Report: A 49-yr-old male farmer mainly growing corn and resident of Jicaltepec, in the semi-arid zone Pinotepa Nacional Oaxaca, approximately 450 km south of Mexico City presented with a dermatosis localised to the left leg at the dorsum of the foot, affecting the third toe (Fig. 13A). The lesion consisted of a tumorous area, with deformation, and nodules with draining sinuses releasing thread-like material including black granules. The dermatosis had begun one and a half yr before, after a trauma with a thorn of cactaceous plant called nopal (Opuntia sp.). These led to progressive swelling of the region and occasional pain (Fig. 13A). Initial treatment included penicillin and sulfametoxazole-trimetroprim. The presumptive clinical diagnosis was that of mycetoma. Direct examination with KOH (10 %) showed some black granules approximately 500 μm in size. The granules were composed of branched, septate, dematiaceous hyphae (Fig. 13B). Clinical specimens cultured on Sabouraud Glucose Agar (SGA) with or without antibiotics (Mycosel) resulted in the growth of a dematiaceous fungus morphologically identified as Cladophialophora sp. Once the diagnosis of eumycetoma had been made, laboratory tests consisted of a complete blood count, blood chemistry and liver function tests; all of these were within normal limits. Foot radiographs (lateral and PA) showed no involvement of bones. Treatment with itraconazole, 200 mg/d was instituted, with significant clinical improvement at 8 mos. Liver and hematological function tests were monitored throughout the treatment period at 4-mo intervals, with no alterations.

Fig. 13.

Clinical manifestations of Eumycetoma caused by Cladophialophora mycetomatis. A. Deformed tumorous area of the foot, with nodules, draining sinuses and discharging purulent fluid. B. Branched black granule, approximately 500 μm in size (in 10 % KOH), with septate hyphae.

The province where the patient lived in the South of Mexico is a very poor region in a semi-arid area climate zone. The majority of inhabitants are farmers growing corn and other vegetables. Cactaceous plants are very common. The trauma with a thorn of a nopal cactus and the micromorphology of the fungus reminded of Cladophialophora carrionii, which is abundant under similar climatic conditions in Venezuela (de Hoog et al. 2007), but according to molecular data the fungus proved to be clearly separate. In addition to Cladophialophora, Exophiala species (particularly E. jeanselmei) are also known to cause mycetoma (de Hoog et al. 2003). Otherwise, subcutaneous infections by members of Chaetothyriales mostly lead to chromoblastomycosis-like infections which are characterised by muriform cells rather than granules, and do not lead to necrosis and draining.

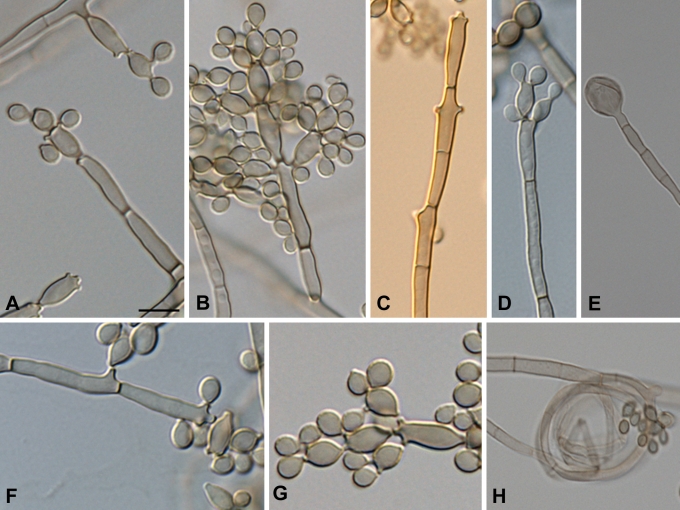

Cladophialophora immunda Badali, Satow, Prenafeta-Boldú & de Hoog, sp. nov. MycoBank MB511844. Figs 10, 14.

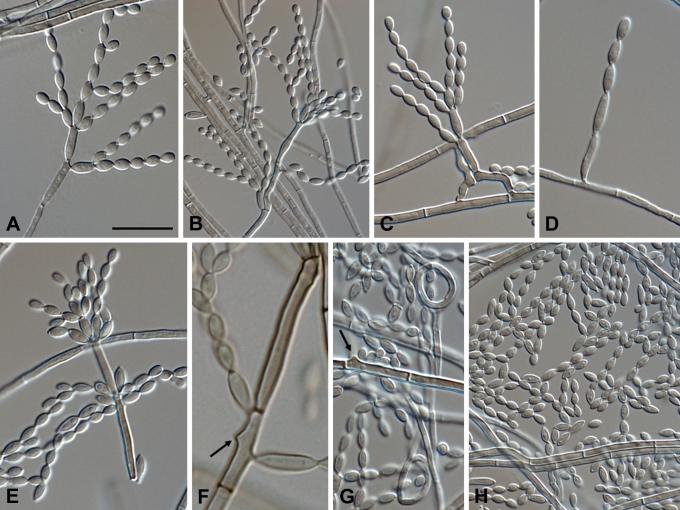

Fig. 10.

Microscopic morphology of C. immunda (CBS 834.96, CBS 109797, CBS 110551, CBS 102227, CBS 102237). Hyphae branched, septate, straight, ascending to erect, Hyphae giving rise to conidiophores. Lemon-shaped to pyriform to guttuliform, narrowed towards one or both ends, coherent or deciduous. Scale bar = 10 μm.

Fig. 14.

Cladophialophora immunda (CBS 834.96, CBS 109797, CBS 110551, CBS 102227, CBS 102237). A–D. Conidiophores and conidial apparatus with T-shaped foot cell and cylindrical, septate, denticulate conidiogenesis. E. Chlamydospores. F–G. Thin-walled, lemon-shaped to pyriform to guttuliform conidia. H. Hyphal coil. Scale bar = 10 μm.

Etymology: Named after its preference for polluted environments.

Coloniae fere lente crescentes, ad 30 mm diam post 14 dies 27–30 °C, velutinae, olivaceo-griseae vel olivaceo-virides, reversum olivaceo-nigrum. Cellulae gemmantes absentes. Hyphae leves, hyalinae vel pallide brunneae, adscendentes vel erectae, 2.5–4 μm latae, saepe circiter aggregatae. Conidiophora micronemata, septata. Conidia holoblastica, dilute brunnea, late fusiformia, unicellularia, levia, catenas cohaerentes formantia vel dilabentia, cicatricibus dilute brunneis, 3.0–4.5×2.5–4.0 μm. Synanamorphe not visa. Chlamydosporae vulgo absentes, Teleomorphe ignota.

Description based on CBS 834.96 at 27 °C on MEA after 2 wks in darkness.

Cultural characteristics: Colonies growing moderately slowly, attaining up to 30 mm diam at 27–30 °C and 10 mm [5 mm in CBS 102237; 20 mm in CBS 110551] at 37 °C. Colonies dark olivaceous-grey [greyish green to olivaceous-green in CBS 102237] with a thin, dark, well-defined margin [wide grey margin in CBS 109797], spreading, downy, velvety; reverse olivaceous-black. Cardinal temperatures: minimum 15 °C, optimum 27–30 °C, maximum 37 °C. No growth at 40 °C.

Microscopy: Budding cells absent. septate hyphae, straight, ascending to erect, smooth, thin-walled, hyaline to pale brown, branched, 2–3 μm wide, frequently forming hyphal strands and coils [no hyphal coils in CBS 102237, CBS 110551]. Hyphae giving rise to conidiophores which are pale brown, erect, mostly straight, branched or unbranched, long, sub-cylindrical and cylindrical to fusiform [fusiform to ellipsoidal in CBS 110551, CBS 102227], 2.5–4 μm wide [with T-shaped foot cell in CBS 102227], with up to 6–8 septa. Conidiogenous cells branched, conspicuously denticulate, smooth-walled, guttulate, with pigmented scars. Conidia one-celled, acropetal, catenulate, sub-hyaline to pale brown [olivaceous brown in CBS 102227, CBS 102237], smooth [slightly verrucose in CBS 109797, CBS 102227], thin-walled, lemon-shaped to pyriform to guttuliform, narrowed towards one or both ends, with pale pigmented scars. Conidia 3.0–4.5 × 2.5–4.0 μm [3–4 × 2–3 μm in CBS 102227], coherent or deciduous. Phialidic synanamorph not seen. Chlamydospores absent [present in CBS 109797]. Teleomorph unknown.

Specimens examined: U.S.A., Georgia, Atlanta, isolated from a sub-cutaneous ulcer on a 68-yr-old female treated with long-term immunosuppressive therapy, (CBS H-20115, holotypus; CDC B-6580 = CBS 834.96, ex-type). Brazil, Paraná, Colombo, isolated from Syagrum romanzoffianum stem, CBS 102227. Brazil, Paraná, isolated from decaying cover vegetable, CBS 102237. Germany, Kaiserslautern, isolated from biofilter inoculated with soil, CBS 109797. The Netherlands, isolated from hydrocarbon-polluted soil, CBS 110551 (Prenafeta-Boldú et al. 2006). Brazil isolated from hydrocarbon-polluted soil, CBS 122636, CBS 122255, CBS 122257, dH 18477, dH 18476, dH 18476, dH 18478 (Satow et al. 2008).

Case Report: According to the description by Padhye et al. (1999), a 68 yr-old-female who underwent long-term immunosuppressive therapy in view of a history of recurrent sinusitis, pneumonia, genital herpes, hysterectomy, chronic hypergammaglobulinemia, low grade lymphoma, Sjogren's disease, rheumatois arthritis. She had not any history of predisposing factor such as truma. The pretibial lesion was non-responsive to cephalexin or ofloxacin. Due to the clinical manifestation of the lesion, a biopsy was performed which consisted of dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Biopsy tissue section was stained by PAS (Fig. 15A) and Gomori's methanamine-silver (GMS, Fig. 15B) stains, showing septate hyphae, moniliform hyphae of different lengths, and thick-walled cells. The melanized fungal elements were within intense infiltrates of neutrophils and necrotizing granulomas with many giant cells. The histopathological observations led to the diagnosis of a subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis infection. The strain was identified as Cladophialophora species (Padhye et al. 1999) resembling C. devriesii and C. arxii. It formed dry conidia in branched acropetal chains inserted on pronounced denticles, fusiform to lemon-shaped conidia, and being involved in a human infection. Unlike C. arxii, the species did not grow above 37 °C. We identified the strain with several environmental isolates by multilocus sequencing (Figs 1, 3 and Table 1). For the environmental strains, a striking association with aromatic hydrocarbons was observed: eight out of twelve strains of C. immunda originated from hydrocarbon-polluted soils. An association with assimilation of toxic monoaromatic compounds and infective potentials have been hypothesised (Prenafeta-Boldú et al. 2006). Black yeasts and their filamentous relatives in the ascomycete order Chaetothyriales are potent degraders of monoaromatic compounds and eventually tend to accumulate in industrial biofilters (Cox et al. 1997, Prenafeta-Boldú et al. 2001, de Hoog et al. 2006).

Fig. 15.

Cladophialophora immunda (CBS 834.96). A. Gomori Methenamine-silver and B. Periodic acid-Schiff stained sections revealed septate hyphae, moniliform hyphae of different lengths, and thick-walled cells. (GMS & PAS × 360)

DISCUSSION

Cladophialophora-like anamorphs are polyphyletic

The genus Cladophialophora is morphologically characterized by poorly or profusely branched chains of dry, rather strongly coherent, moderately melanized conidia. Our results show that this Cladophialophora anamorphic type is convergent, as the genus Cladophialophora is polyphyletic. In our combined phylogeny of the Chaetothyriales (Fig. 1), the plant-associated species (C. hostae, C. scillae, C. proteae, C. sylvestris, C. minutissima, and C. humicola) appeared to be closer to Ceramothyrium carniolicum (a putative member of the family of Chaetothyriaceae), and only distantly related to most remaining Cladophialophora species. It is interesting to note that Cladophialophora species that are consistently associated with pathology to humans mostly belong to the Herpotrichiellaceae, a family particularly diverse in human opportunists (e.g., Exophiala, Fonsecaea, Rhinocladiella, and Veronaea). The lineages to which the plant-associated species of Cladophialophora (lineages 2, 3 and 4) belong contain comparatively few human opportunists, all of them causing only mild cutaneous infections (e.g., Phialophora europaea, and Cyphellophora laciniata), or traumatic infection (Cladophialophora modesta).

Similar Cladophialophora-like morphologies have also been observed in several unrelated environmental fungi, particularly in Cladosporium, Pseudocladosporium and Devriesia (Braun et al. 2003, Crous et al. 2007, Seifert et al. 2004). These genera are assigned to different families within the Dothideales and the Capnodiales, two ascomycete orders for which species are only exceptionally encountered in a clinical setting. Moreover, the conidial scars have a pale pigmentation in Cladophialophora, which is in contrast to members of the saprobic genera Cladosporium, Devriesia and Pseudocladosporium, where pronounced darker conidial scars are present. Furthermore, conidiophores in most Cladophialophora species are poorly differentiated, while those of Cladosporium species are usually erect and significantly darker than the rest of the mycelium. Finally, conidial chains of Cladophialophora species are coherent, while those of Cladosporium detach very easily.

Evolution of pathogenicity in Cladophialophora

Melanin pigments are common to all Chaetothyriales, although little is known concerning the pathogenic mechanisms by which these fungi cause disease, particularly in immunocompetent individuals. However, the production of melanin was shown to be involved in pathogenicity. Melanins are pigments of high molecular weight formed by oxidative polymerization of phenolic compounds and usually are dark brown or black; in case of fungal pathogens melanin appears to function in virulence by protecting fungal cells against fungicidal oxidants, by impairing the development of cell-mediated responses, interfere with complement activation and reduce the susceptibility of pigmented cells to antifungal agents. In the environment, they protect organisms against environmental factors (Butler et al. 1998, Jacobson 2000).

Another putative virulence factor is thermotolerance. According to de Hoog et al. (2000), species of Cladophialophora show a differential maximum growth at temperatures more or less coinciding with clinical predilections, species causing systemic infections being able to grow at 40 °C. The agents of chromoblastomycosis have a growth maximum at 37 °C, while a mildly cutaneous species, such as C. boppii, is not able to grow at this temperature (de Hoog et al. 2000). In the present study, all studied strains of Cladophialophora had an optimum growth around 27 °C, and were still able to grow at 37 °C, but not at 40 °C (Fig. 4). This observation agrees with the prevalent nature of these species as environmental saprobes, and their potential to cause superficial infections in humans, similarly to other opportunistic species. Tolerance of human body temperature is an essential requirement for pathogenicity, but this trait may have incidentally been acquired via adaptation to warm environmental habitants, such as hot surfaces in semiarid climates.

Early experiments involving the inoculation of Cladophialophora in several species of cold-blooded animals have shown the abundant production of characteristic muriform cells in vivo (Trejos 1953). For C. yegresii and C. carrionii, the muriform propagules are also present in cactus spines (de Hoog et al. 2007); in this plant host, they can be regarded as an extremotolerant survival phase, and are likely to play an essential role in the natural life cycle of these organisms. The capacity of some Herpotrichiellaceae to grow in a meristematic form both in human hosts and in extreme environmental conditions supports the suggestion that the muriform cells may indeed be a main virulence factor in the development of the disease, representing an adaptation to the conditions prevailing in host tissues. The conversion of hyphae to muriform cells can be induced in vitro under acidic conditions (pH = 2.5) and low concentration of calcium. In the present study, we observed different morphogenetic responses between environmental and clinical species of Cladophialophora. C. subtilis isolated from ice tea, under the above circumstances formed structures resembling muriform cells at 27 °C which became larger when incubated at 37 °C. The pathogenic C. samoënsis and C. immunda also produced muriform cells at 37 °C. Muriform cells were not observed, neither on the plant-associated species (plant leaving) of Cladophialophora, nor in the C. mycetomatis isolated from both environment and a patient.

CONCLUSIONS

Some members of Herpotrichiellaceae grow as ordinary filamentous moulds in pure culture, but can also be induced to form strongly melanized, isodiametrically expanding meristematic cells in vitro. This type of cells, dividing by sclerotic fission, is characteristically found in chromoblastomycosis. However, they can also be observed when these fungi grow in natural niches, in particular the ones characterized as extreme (e.g., F. pedrosoi within dried cactus thorns; Sterflinger et al. 1999) and Vicente et al. (2008) have shown that the hydrocarbon-polluted environments yielded yet another spectrum of chaetothyrialean fungi. A generalized suite of adaptations to extreme environments, including melanin production and meristematic growth, as well as thermotolerance, is suggested to contribute to pathogenic potential (Gueidan et al. 2008). Many of the natural and artificial habitats that are associated with growth of Herpotrichiellaceae, such as decaying tree bark and creosoted poles and ties, are likely to favor fungi that, in addition to being able to break down the aromatic compounds occurring in these substrata, have a generalized set of adaptations to conditions that at least occasionally become highly stressful (extreme temperatures, pH, low availability of nutrients and growth factors, etc.). Many of these adaptations may incidentally predispose fungi towards human opportunistic pathogenesis.

Acknowledgments

This research was financially supported by a grant of the Ministry of Health and medical education of Islamic Republic of Iran (No. 13081), which we gratefully acknowledge. The authors acknowledge Walter Gams for his comments on the manuscript and for providing Latin descriptions. Grit Walther is gratefully acknowledged for helping in part of description and drawing. We thank Marjan Vermaas for providing the photographic plates. Kasper Luijsterburg is thanked for technical assistance.

Taxonomic novelties: Cladophialophora samoënsis Badali, de Hoog & Padhye, sp. nov., Cladophialophora subtilis Badali & de Hoog, sp. nov., Cladophialophora mycetomatis Badali, de Hoog & Bonifaz, sp. nov., Cladophialophora immunda Badali, Satow, Prenafeta-Boldú, Padhye & de Hoog, sp. nov.

References

- Badali H, Carvalho VO, Vicente V, Attili-Angelis D, Kwiatkowski IB, Gerrits van den Ende AHG, Hoog GS de (2008). Cladophialophora saturnica sp. nov., a new opportunistic species of Chaetothyriales revealed using molecular data. Medical Mycology 7: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borelli D (1980). Causal agents of chromoblastomycosis (Chromomycetes). Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Mycoses pp. 335–340.

- Braun U (1998). A monograph of Cercosporella, Ramularia and allied genera(Phytopathogenic Hyphomycetes). Vol. 2. IHW-Verlag, Eching.

- Braun U, Crous PW, Dugan F, Groenewald JZ, Hoog GS de (2003). Phylogeny and taxonomy of Cladosporium-like hyphomycetes, including Davidiella gen. nov., the teleomorph of Cladosporium s. str. Mycological Progress 2: 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Braun U, Feiler U (1995). Cladophialophora and its teleomorph. Microbiological Research 150: 81–91. [Google Scholar]

- Butler MJ, Day AW (1998). Fungal melanins: a review. Canadian Journal of Microbiology 44: 1115–1136. [Google Scholar]

- Carbone I, Kohn LM (1999). A method for designing primer sets for speciation studies in filamentous ascomycetes. Mycologia 91: 553–556. [Google Scholar]

- Cox HHJ, Moerman RE, van Baalen S, van Heiningen WNM, Doddema HJ & Harder W (1997). Performance of a styrene degrading biofilter containing the yeast Exophiala jeanselmei. Biotechnology & Bioengineering 53: 259–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Gams W, Wingfied MJ, Van Wyk PS (1996). Phaeoacremonium gen. nov associated with wilt and decline diseases of woody hosts and human infections. Mycologia 88: 786–796. [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Schubert K, Braun U, Hoog GS de, Hocking A D, Shin H-D, Groenewald JZ (2007). Opportunistic, human-pathogenic species in the Herpotrichiellaceae are phenotypically similar to saprobic or phytopathogenic species in the Venturiaceae. Studies in Mycology 58: 185–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey ML, Currah RS (2007). A new species of Cladophialophora (Hyphomycetes) from boreal and montane bryophytes. Mycological Research 111: 106–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon DM, Shadomy HJ, Shadomy S (1980). Dematiaceous fungal pathogens isolated from nature. Mycopathologia 70: 153–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gams W, Verkley GJM, Crous PW (1998). CBS Course of Mycology, 4th ed. Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Utrecht.

- Gargas A, Taylor JW (1992). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers for amplifying and sequencing 18s rDNA from lichenised fungi. Mycologia 84: 589–592. [Google Scholar]

- Gezuele E, Mackinnon JE, Conti-Diaz IA (1972). The frequent isolation of Phialophora verrucosa and Fonsecaea pedrosoi from natural sources. Sabouraudia 10: 266–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass NL, Donaldson G (1995). Development of primer sets designed for use with PCR to amplify conserved genes from filamentous ascomycetes. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 61: 1323–1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh KS, Padhye AA, Ajello L (1982). A Samoan case of chromoblastomycosis caused by Cladophialophora ajelloi. Sabouraudia 20: 1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueidan C, Ruibal C, Hoog GS de, Gorbushina A, Untereiner WA, Lutzoni F (2008). A rock-inhabiting ancestor for mutualistic and pathogen-rich fungal lineages.Studies in Mycology 61: 111–119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase G, Sonntag L, Melzer-Krick B, Hoog GS de (1999). Phylogenetic inference by SSU gene analysis of members of the Herpotrichiellaceae, with special reference to human pathogenic species. Studies in Mycology 43: 80–97. [Google Scholar]

- Hillis DM, Bull JJ (1993). An empirical test of bootstrapping as a method for assessing confidence in phylogenetic analysis, Systematic Biology 42: 182–192. [Google Scholar]

- Ho MH-M, Castañeda RF, Dugan FM, Jong SC (1999). Cladosporium and Cladophialophora in culture: descriptions and an expanded key. Mycotaxon 72: 115–157. [Google Scholar]

- Honbo S, Padhye AA, Ajello L (1984). The relationship of Cladosporium carrionii to Cladophialophora ajelloi. Sabouraudia 22: 209–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoog GS de, Gerrits van den Ende AHG (1998). Molecular diagnostics of clinical strains of filamentous basidiomycetes. Mycoses 41: 183–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoog GS de, Göttlich E, Platas G, Genilloud O, Leotta G, Brummelen J van (2005). Evolution, taxonomy and ecology of the genus Thelebolus in Antarctica. Studies in Mycology 51: 33–76. [Google Scholar]

- Hoog GS de, Guarro J, Gené J, Figueras MJ (2000). Atlas of clinical fungi, 2nd ed. Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Utrecht, The Netherlands and Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Reus, Spain.

- Hoog GS de, Guého E, Masclaux F, Gerrits van den Ende AHG, Kwon-Chung KJ & McGinnis MR (1995). Nutritional physiology and taxonomy of human-pathogenic Cladosporium-Xylohypha species. Journal of Medical & Veterinary Mycology 33: 339–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoog GS de, Nishikaku AS, Fernández Zeppenfeldt G, Padín-González C, Burger E, Badali H, Gerrits van den Ende AHG (2007). Molecular analysis and pathogenicity of the Cladophialophora carrionii complex, with the description of a novel species. Studies in Mycology 58: 219–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoog GS de, Vicente VA, Caligiorne RB, Kantarcioglu AS, Tintelnot K, Gerrits van den Ende AHG, Haase G (2003). Species diversity and polymorphism in the Exophiala spinifera clade containing opportunistic black yeast-like fungi. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 41: 4767–4778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoog GS de, Zeng JS, Harrak MJ, Sutton DA (2006). Exophiala xenobiotica sp. nov., an opportunistic black yeast inhabiting environments rich in hydrocarbons. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 90: 257–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horré R, Hoog GS de (1999). Primary cerebral infections by melanized fungi: a review. Studies in Mycology 43: 176–193. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson ES. Pathogenic roles for fungal melanins (2000). Clinical Microbiology Reviews 13: 708–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddison WP, Maddison DR (2003). MacClade: Analysis of Phylogeny and Character Evolution, v. 4.6, Sinauer, Sunderland, MA. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Masclaux F, Guého E, de Hoog GS, Christen R (1995). Phylogenetic relationships of human-pathogenic Cladosporium (Xylohypha) species inferred from partial LS rRNA sequences. Medical Mycology 33: 327–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason-Gamer RJ and Kellogg EA (1996). Testing for phylogenetic conflict among molecular datasets in the tribe Triticeae (Graminae). Systematic Biology 45: 524–545. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza L, Karuppayil SM, Szaniszlo PJ (1993). Calcium regulates in vitro dimorphism in chromoblastomycotic fungi. Mycoses 36: 15–-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padhye AA, Dunkel JD, Winn RM, Weber S, Ewing EP, Hoog GS de (1999). Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis caused by an undescribed Cladophialophora species. Studies in Mycology 43: 172–175. [Google Scholar]

- Prenafeta-Boldú FX, Kuhn A, Luykx D, Anke H, Groenestijn JW van, Bont JAM de (2001). Isolation and characterization of fungi growing on volatile aromatic hydrocarbons as their sole carbon and energy source. Mycological Research 105: 477–484. [Google Scholar]

- Prenafeta-Boldú FX, Summerbell R, Hoog GS de (2006). Fungi growing on aromatic hydrocarbons: biotechnology's unexpected encounter with biohazard? FEMS Microbiology Reviews 30: 109–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satow MM, Attili-Angelis D, Hoog GS de, Angelis DF, Vicente VA (2008). Selective factors involved in oil flotation isolation of black yeasts from the environment.Studies in Mycology 61: 157-163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert KA, Nickerson NL, Corlett M, Jackson ED, Louis-Seize G, Davies RJ (2004). Devriesia, a new hyphomycete genus to accommodate heat-resistant, Cladosporium-like fungi. Canadian Journal of Botany 82: 914–926. [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A, Hoover P, Rougemont J (2008). A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML Web-Servers. Systematic Biology, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sterflinger K, Hoog GS de, Haase G (1999). Phylogeny and ecology of meristematic ascomycetes. Studies in Mycology 43: 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Sudhadham M, Dorrestein GM, Prakitsin S, Sivichai S, Chaiyarat R, Prakitsin S, Menken SBJ, Hoog GS de (2008). The neurotropic black yeast Exophiala dermatitidis has a possible origin in the tropical rain forest. Studies in Mycology 61: 145–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JW, Jacobson DJ, Kroken S, Kasuga T, Geiser DM, Hibbett DS, Fisher MC (2000). Phylogenetic species recognition and species concepts in fungi. Fungal Genetics and Biology 31: 21–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trejos A (1954). Cladosporium carrionii n. sp. and the problem of cladosporia isolated from chromoblastomycosis. Revista de Biologia Tropical 2: 75–112. [Google Scholar]

- Vicente VA, Attili-Angelis D, Filho FQT, Pizzirani-Kleiner AA (2001). Isolation of herpotrichiellaceous fungi from the environment. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology 32: 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Vicente VA, Attili-Angelis D, Pie MR, Queiros-Telles F, Cruz LM, Najafzadeh MJ, Hoog GS de, Zhao J, Pizzirani-Kleiner A (2008). Environmental isolation of black yeast-like fungi involved in human infection. Studies in Mycology 61: 136–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor J (1990). Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: PCR Protocols: a guide to methods and applications (Innis MA, Gelfand DH, Sninsky JJ, White TJ, eds). Academic Press, San Diego, California: 315–322.