Abstract

Spine motion has been described to have two regions, a neutral zone where lumbar rotation can occur with little resistance and an elastic zone where structures such as ligaments, facet joints and intervertebral disks resist rotation. In vivo, the passive musculature can contribute to further limiting the functional neutral range of lumbar motion. Movement out of this functional neutral range could potentially put greater loads on these structures. In this study, the range of lumbar curvature rotation was examined in twelve healthy, untrained volunteers at four torso inclination angles. The lumbar curvature during straight-leg lifting tasks was then defined as a percentage of this range of possible lumbar curvatures. Subjects were found to remain neutrally oriented during the flexion phase of a lifting task. During the extension phase of the lifting task, however, subjects were found to assume a more kyphotic posture, approaching the edge of the functional range of motion. This was found to be most pronounced for heavy lifting tasks. By allowing the lumbar curvature to go in a highly kyphotic posture, subjects may be taking advantage of stretch-shortening behavior in extensor musculature and associated tendons to reduce the energy required to raise the torso. Such a kyphotic posture during extension, however, may put excessive loading on the elastic structures of the spine and torso musculature increasing the risk of injury.

Keywords: Lumbar spine, lifting, manual materials handling

Introduction

Low back pain and injury are significant public health problems. In United States, up to 85% of the population suffer low back pain at least once in their lifetime [ Lively, 2002, and Pai and Sundaram, 2004]. In the United States, the total annual costs of back pain are estimated to range from $20 – $50 billion [Nachemson, 1992, Pai and Sundaram, 2004]. Jobs involving flexion tasks and lifting heavy loads have been shown to be associated with a higher incidence of low back injuries [Marras et al., 1995, Punnett et al., 1991]. Understanding how subjects perform these flexion and lifting tasks is, therefore, important to understanding and preventing low back injuries.

When examining flexion tasks and the low back, the motion of the spine is a critical component. Panjabi [Panjabi, 1992b] described the motion of spinal segments with two regions, the neutral zone where rotation of the spinal segments meets little resistance and the elastic zone where soft tissue restraints such as ligaments, facet joints (in extension) and the intervertebral disk (in flexion) provide resistance to rotation. At the extremes of the neutral zone, tension in the posterior ligaments (in flexion), moment loading of the intervertebral disc (in flexion) and/or compression in the facet joints (in extension) are engaged, limiting further motion [Panjabi,1992a, Panjabi, 1992b, Panjabi, 2003].

This neutral zone of spinal segments has been typically measured on cadaveric specimen. In the in vivo spine, in addition to the passive structures of the spine, the stiffness characteristics of the musculature and tendons may also limit the rotation of the lumbar spine. When inactive, muscle demonstrates a nonlinear stiffness that is close to zero at neutral length and increases dramatically as the muscle is lengthened past its operating length [McMahon, 1982]. This nonlinear stiffness of muscle may limit the range of lumbar postures that can be achieved without resistance. With a number of muscle groups (such as the psoas or erector spinae) crossing several of joints, such muscles may also contribute to interactions between the range of possible lumbar rotation and the orientation of other joints.

It has been suggested that when the spine segments rotate into the elastic zone, the ligamentous tissues are loaded causing strain in the ligaments and eventually viscoelastic stretching of the ligament [Solomonow et al., 1998]. It is possible that such loading of the passive tissues could cause damage directly. In addition, in experiments examining supraspinous ligament stretch in cats, Solomonow et al., [1998] found the viscoelastic stretching of the ligaments either statically or cyclically resulted in a loss in the neuromotor response. Studies of flexion-relaxation, a position of extreme torso flexion where the upper body is solely supported by the passive tissues of the spine and where extensor muscle activity drops to zero, have also shown viscoelastic changes in these passive tissues [Olson et al., 2004].

In addition to the passive tissues of the spine, the musculature and associated tendons could also be at risk of damage if stretched beyond their neutral lengths. Witvrouw et al. [2006] suggested more frequent tendon injuries are observed with quick stretching of the tendon. Muscle fiber damage has also been observed with repetitive lengthening of contracted muscle [Butterfield and Herzog, 2006]. Butterfield and Herzog [2006] also observed a reduction in muscle mechanical properties after repetitive lengthening cycles of the muscle-tendon unit.

While repetitive lengthening of muscle and tendon beyond its neutral length can cause damage, such stretching of the muscle-tendon unit has been demonstrated as a powerful method of energy conservation in a number of cyclic activities such as running, jumping, snatch-lifting and flying (in animals) [Biewener, 2003, Ettema, 2001, Roberts, 2002, Gourgoulis, 2000]. This cyclic stretch, generally referred to as a stretch-shortening cycle, has been demonstrated to allow energy to be stored during the stretch of the muscle-tendon unit and released during the subsequent shortening of the unit. Energy is believed to be stored in the elastic components of the muscle and tendon, particularly the series elastic of the tendon. It is possible that subjects engaged in repetitive lifting may use a similar mechanism to reduce the energy required for lifting. In order to better understand injury risk as well as the possible stretch-shortening action of the trunk musculature, it is important to understand the interaction with the limits of lumbar motion.

As a person moves, a range of lumbar curvatures is available for any torso inclination. For example, one can slouch (more kyphotic) or stand up straight (more lordotic). Such changes in lumbar curvature at a given torso inclination are modulated by the tilt of the pelvis and the thorax. This range of curvature can be associated with the neutral range of lumbar curvatures where there is little resistance to rotation from either the passive structures of the spine or the torso musculature.

Few studies have examined whether lumbar postures in lifting tasks might approach the limits of lumbar rotation other than in extreme trunk flexion [Olson et al., 2004, Scannell et al.,2003]. Scannell et al. examined the ability of subjects to be trained to stand and sit with their lumbar spine within the neutral zone [Scannell et al.,2003]. Although 2/3 of these subjects originally assumed postures at either the hypolordotic or hyperlordotic edge of their lumbar range, by the end of an exercise program they assumed postures closer to the mid-range. This research illustrates the ability to examine lumbar range in a variety of trunk flexion postures as well as the possibility that lumbar posture could be adjusted with training [Scannell et al.,2003].

Lumbar-pelvic coordination experiments measure the relationship between lumbar curvature and torso flexion in various tasks. A number of authors have examined lumbar pelvic co-ordination in lifting tasks. Marras et al. reported that lumbar kyphosis increased significantly at peak trunk flexion [Marras and Granata, 1997]. Granata et al. reported that dynamic lifting parameters (load and lifting velocity) influenced lumbar pelvic co-ordination and motion of the lumbar spine [Granata and Sanford, 2000]. McKean and Potvin [2001], while reporting no difference in peak lumbar angle, found greater lumbar angles on extension relative to flexion during both freestyle and constrained lifts (while allowing subjects to flex their knees as they felt comfortable). A number of studies have also used the relative phase lag between lumbar and hip flexion to examine lumbar-pelvic coordination of a lifting task [Dieen et al., 1996, Dieen et al., 1998, Burgess-Limerick et al., 1992]. Dieen et al. [1996] and Burgess-Limerick et al. [1992] demonstrated using phase lag between the hip and lumbar spine that the hip precedes the spine with extension during a lift. Dieen et al [1996] further demonstrated increased phase lag with straight leg lifting relative to squat lifting. Dieen et al. [1998] also demonstrated that the phase lag increases as a consequence of fatigue in freestyle lifting. However, none of the previous authors have examined how this co-ordination interacts with range of physically possible lumbar angles or the lumbar range of motion. The object of the study was to examine a variety of lifting tasks to assess lumbar-pelvic coordination as a function of the range of lumbar curvature in order to examine how extreme lumbar postures are encountered in lifting activities. In addition, the effects of heavy and fast lifting tasks on the lumbar curvature as a function of the range were examined.

Methods

Eleven healthy volunteers (4 female, 7 male, height 1.72 m (SD .09), weight 71 kg (SD 9)), with ages ranging from 22–32 years participated in this study. This study was approved by the human subjects committee of the University of Kansas and consent was obtained from all subjects. All the participants were healthy and reported no instance of low back pain within the last year or musculoskeletal disorder that would limit normal torso flexion.

An electromagnetic motion analysis system (Motion Star, Ascension Tech., VT) was used to collect position and orientation of three electromagnetic sensors. This system has a resolution of 0.08 cm and 0.1 degrees and an RMS accuracy of 0.76 cm and 0.5 degrees. The three sensors were attached to the skin with double-sided tape over the T10 spinous process, over the S1 spinous process, and over the manubrium. This kinematic data was collected at a frequency of 30 Hz for each trial. Using the position of the T10 and S1 sensors, trunk inclination angle was determined as the angle between a line connecting these sensors and vertical. The difference in angular orientation between the T10 and S1 sensors in the sagittal plane was defined as the lumbar curvature. The manubrium marker allowed detection of trunk rotation and asymmetry of motion. This configuration is consistent with previous literature on lumbar position sense and lumbar-pelvic coordination [Granata and Sanford, 2000, Gade and Wilson, 2003, Wilson and Granata, 2003].

The experiment consisted of 1) assessment of maximum effort and selection of lifting weight, 2) assessment of range of curvatures at four inclination angles (0°, 30°, 60°, & 90° (0, 0.52, 1.05 and 1.57 radians)) and 3) four sets of lifting tasks (light-fast, light-slow, heavy-fast, and heavy-slow).

To assess maximal effort, subjects were asked to stand on a force plate at a trunk inclination angle of 45° (0.79 radians) with respect to the vertical. They were then asked to pull vertically on a tethered handle as hard as possible for five seconds. They were asked to repeat this maximal exertion three times. The mean maximum effort of three trials was defined as the maximum effort.

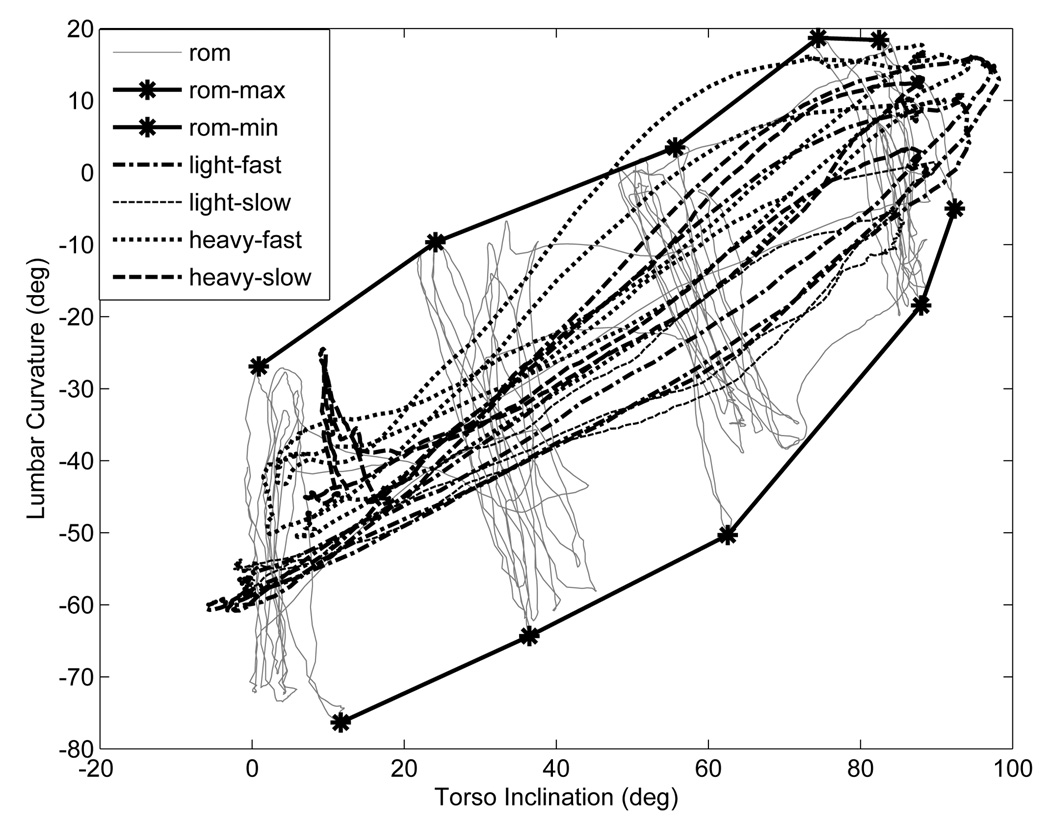

Before conducting the experimental protocol, the range of lumbar curvature for the four inclination angles (0, 30, 60 and 90 degrees (0, 0.52, 1.05 and 1.57 radians)) was determined. A real-time visual display of torso inclination and lumbar curvature was provided to the subjects. At each of the four torso inclination angles, subjects were instructed to hold the inclination angle constant while rotating their thorax and pelvis to change the lumbar curvature. Subjects were allowed to practice these movements until they became comfortable with the equipment. Subjects were then instructed to assume the maximum (kyphotic) and then the minimum (lordotic) lumbar curvature possible while maintaining one of the four torso inclination angles. Subjects were asked to repeat these extreme lumbar curvatures three times at each of the four torso inclination angles. Plotting lumbar curvature on the y-axis and trunk inclination on the x-axis, the lumbar curvature range was defined as the maximum and minimum obtained lumbar curvatures obtained at each of the trunk inclination angles (Figure 2 and Figure 3). A linear interpolation was used to determine the lumbar range between the measured trunk inclination angles. Outside of the measured range of trunk inclination, lumbar range was kept constant.

Figure 2.

The range of lumbar curvature was measured for each subject prior to the lifting tasks. This figure illustrates a typical subject. Lumbar curvature during the lifting tasks generally fell within the measured range.

Figure 3.

The lumbar curvature range of motion was measured for each subject. This figure illustrates the average maximum and minimum range values as a function to torso inclination. The grey region signifies one standard deviation above and below the average values. As torso inclination increases, the range of lumbar curvatures shifts from more lordotic (negative) to more kyphotic (positive).

Subjects were then asked to perform the following lifting tasks in random order: 1) heavy-slow, 2) heavy-fast, 3) light-slow, and 4) light-fast. A 0.9 kg milk crate with no added weight was defined as the light condition. Subjects were told to keep their hands comfortably gripping padded handles of the crate for all lifting conditions to maintain consistent hand position. Sandbags equivalent to 40% of their maximal effort were added to the crate for the heavy condition. Slow and fast trunk flexion speeds were defined as 25 and 100 deg/sec (0.44 and 1.75 radians/sec) respectively. Subjects were asked to lift the box up from ground level to his or her waist, hold it for 5 seconds and then lower the box to the ground at the speed displayed on a computer screen. Subjects were asked to perform these lifting tasks while maintaining the feet in a consistent position, shoulders width apart and while maintaining comfortably straight knees. Each lifting task was repeated three times with speed controlled by having the subject match a real-time visual feedback of their torso inclination to a target torso inclination (Figure 1). Subjects were allowed to practice until they became comfortable with the equipment and were familiar with the tasks. A total of 5 lifting cycles were performed for each lifting condition. A five minute rest was given between lifting tasks.

Figure 1.

Subjects were asked to lift at a constant rate of torso flexion using a visual feedback. The subjects were given a display of their target torso flexion (right) and their measured torso flexion (left) and were asked to match the two displays.

The range of lumbar curvature motion measured initially was used to define the bounds of the range of lumbar curvature. Lumbar curvature was examined as a percent of this range during the lifting tasks. Maximally lordotic was considered to be 0% of the range and maximally kyphotic was considered to be 100% of range. The limits of range of lumbar curvature were therefore projected on a 0 to 100% scale (Figure 2 and 3). These percent of range values for lumbar curvature were assessed as a function of torso inclination for each of the lifting tasks.

To analyze statistical differences between phases of the lifting tasks, the lifting was split into extension and flexion phases. Each phase was divided into segments by examining average lumbar curvature during 0–20%, 20–40%, 40–60%, 60–80%, and 80–100% of total torso flexion for the lift. A Huynh-Feldt adjusted, repeated-measures ANOVA was used to examine the effects of the independent variables, torso inclination, direction of motion, lifting weight and lifting speed, on the dependent variable, lumbar curvature as a percentage of range. The Huynh-Feldt correction was used to adjust for violations in the sphericity assumption. To further investigate segments of the lifting task engaging the extremes of the range of lumbar curvature, two-way, Huynh-Feldt repeated measures ANOVAs were performed for each of these segments with the independent variables of speed and weight. These tests were determined to be significant for a p<0.05.

Results

The lumbar curvature range measured in this study was found to change with torso inclination. The maximum and minimum lumbar curvature both shifted from more lordotic in upright trunk postures to more kyphotic in flexed trunk postures (Figure 3). The width of the range (the difference between maximum and minimum lumbar curvature) also decreased at higher torso inclinations. Using the lumbar curvature range for each subject, the lumbar-pelvic coordination for that subject could be mapped to identify at what stages of a lifting task the subject might approach the edges of their range of motion (Figure 2).

The lumbar-pelvic coordination was observed to have different patterns in flexion and extension with subjects maintaining a mid-range lumbar curvature (52%) during the flexion phase of lifting and a highly kyphotic lumbar curvature at the mid-region of the extension phase of lifting (Table 1). In extension, subjects moved from the middle of their range (59%) to a more kyphotic posture (78%) ending at a more neutral posture (47%) (Table 1, Figure 4). This pattern was observed to be particularly pronounced in the heavy-slow lifting condition (Figure 4).

Table1.

Lumbar curvature, represented as a percentage of the range of lumbar curvature, was assessed during each of the lifting tasks. Lifting tasks were divided into segments of 20% of the torso flexion during the lift and the lumbar curvature was averaged within that segment.

| Torso Inclination | → | FLEXION | → | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (% of Lift Inclination) | 0–20 | 20–40 | 40–60 | 60–80 | 80–100 | |

| Light-Fast | 37.4 (SD 50.9) | 44.7 (SD 21.5) | 45.0 (SD 24.1) | 44.0 (SD 32.9) | 42.5 (SD 54.3) | |

| Light-Slow | 35.6 (SD 40.5) | 46.4 (SD 28.5) | 47.8 (SD 29.7) | 53.4 (SD 27.2) | 50.6 (SD 39.0) | |

| Heavy-Fast | 35.5 (SD 54.2) | 46.7 (SD 23.7) | 51.4 (SD 21.3) | 61.2 (SD 23.5) | 62.6 (SD 43.0) | |

| Heavy-Slow | 49.8 (SD 45.9) | 54.6 (SD 16.2) | 66.0 (SD 20.5) | 79.3 (SD 26.3) | 81.8 (SD 40.5) | |

| Torso Inclination | → | EXTENSION | → | |||

| (% of Lift Inclination) | 80–100 | 60–80 | 40–60 | 20–40 | 0–20 | |

| Light-Fast | 54.1 (SD 45.9) | 70.7 (SD 18.3) | 70.5 (SD 21.0) | 64.5 (SD 26.7) | 42.2 (SD 54.0) | |

| Light-Slow | 46.8 (SD 39.8) | 68.5 (SD 20.2) | 70.8 (SD 21.7) | 64.9 (SD 22.2) | 43.5 (SD 42.6) | |

| Heavy-Fast | 60.4 (SD 50.6) | 76.7 (SD 23.3) | 78.4 (SD 28.1) | 73.0 (SD 31.7) | 44.2 (SD 48.9) | |

| Heavy-Slow | 75.9 (SD 45.2) | 92.4 (SD 25.6) | 92.4 (SD 21.9) | 84.3 (SD 25.9) | 60.7 (SD 38.6) | |

Figure 4.

The average lumbar curvature (expressed as a percentage of the range) was found to remain within the mid-range during the descent phase of the lift (dashed lines) becoming more kyphotic (higher) during the ascent phase (solid lines). Lifting a heavy object was found to increase the kyphosis during the ascent phase (dark, thick lines).

A repeated-measures ANOVA of the data demonstrated significant effects of both the direction of motion (p<0.01, Table 2) and the weight on the lumbar curvature (p<0.01, Table 1). In addition a significant interaction was also found between the direction of motion and the torso inclination (p<0.01, Table 2).

Table 2.

A Huynh-Feldt, repeated measures ANOVA was used to examine the effects of the independent variables, torso flexion, weight, speed, and direction, on the dependent variable, lumbar curvature as a percentage of range. Epsilon from the Mauchly’s test of sphericity and the Huynh-Feldt adjusted degrees of freedom (df) are reported. The F-statistic and the significance (p) are also reported. Significant results (p<0.05) are highlighted.

| epsilon | df | F | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direction | 1.000 | 1.000 | 35.662 | 0.000 |

| Weight | 1.000 | 1.000 | 19.961 | 0.001 |

| Speed | 1.000 | 1.000 | 2.382 | 0.154 |

| TF | 0.581 | 2.324 | 1.664 | 0.209 |

| Dir*Wt | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.997 |

| Dir*Speed | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.393 | 0.265 |

| Dir*TF | 0.549 | 2.840 | 18.682 | 0.000 |

| Wt*Speed | 1.000 | 1.000 | 2.575 | 0.140 |

| Wt*TF | 0.436 | 1.000 | 1.869 | 0.187 |

| Speed*TF | 0.552 | 1.745 | 0.349 | 0.730 |

To examine the phases of lifting where the most extreme postures were found, repeated measures ANOVA were also performed for the each segment during the extension phase with weight and speed as independent variables. When rising from 100% of torso flexion, the weight was found to have a significant effect on lumbar curvature at 80–100% (p<0.05), 60–80% (p<0.05), 40–60% (p<0.01) and 20–40% (p<0.01) of torso flexion (Table 3). Strong trends were also observed in the interaction between weight and speed although none of these was statistically significant (Table 3). Speed was not found to have a significant effect at any of these torso flexions (Table 3).

Table 3.

Two-way, repeated measures ANOVAs were used to further examine the effect of weight and speed during the ascent phase of lifting for each of torso flexion segment. For four of the five segments, weight was found to have a significant effect on the lumbar curvature.

| Torso Inclination (% of Lift Inclination) | Variable | epsilon | df | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–20 | Weight | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.803 | 0.209 |

| Speed | 1.000 | 1.000 | 2.410 | 0.152 | |

| Wt*Speed | 1.000 | 1.000 | 3.867 | 0.078 | |

| 20–40 | Weight | 1.000 | 1.000 | 19.030 | 0.001 |

| Speed | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.306 | 0.280 | |

| Wt*Speed | 1.000 | 1.000 | 4.870 | 0.052 | |

| 40–60 | Weight | 1.000 | 1.000 | 14.255 | 0.004 |

| Speed | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.422 | 0.261 | |

| Wt*Speed | 1.000 | 1.000 | 2.654 | 0.134 | |

| 60–80 | Weight | 1.000 | 1.000 | 7.945 | 0.018 |

| Speed | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.430 | 0.259 | |

| Wt*Speed | 1.000 | 1.000 | 4.307 | 0.065 | |

| 80–100 | Weight | 1.000 | 1.000 | 7.663 | 0.020 |

| Speed | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.284 | 0.606 | |

| Wt*Speed | 1.000 | 1.000 | 3.483 | 0.092 |

Discussion

In this study, the range of curvature was assessed by measuring the range of lumbar curvature angles a subject could achieve at several torso inclination angles (0°, 30°, 60°, & 90°). The torso inclination was found to have a dramatic effect on the in vivo range of lumbar motion. With increasing torso inclination both the upper and lower bounds of the range of lumbar motion increased, moving from more lordotic to more kyphotic postures. While the width of the range increase from 0 to 30 degrees of torso inclination, it decreased as torso inclination approached 90 degrees. This range, measured for each subject, represents the possible lumbar curvatures that could be assumed during any straight leg trunk flexion task. The limits of this range could be a result of the nonlinear stiffness characteristics of the passive structures of the spine (ligaments and facet joints for example), the nonlinear stiffness characteristics of the muscle/tendon units crossing the lumbar region of the torso and/or limits of strength in the torso musculature. While it is not possible from this data to distinguish the various contributors to the lumbar curvature limits, these limits give an estimate of where elastic resistance to further rotation of the lumbar spine may exist. The changing bounds of the range with increased torso inclination suggest that the muscles may be particularly important in creating these limits. By assessing the lumbar curvature during lifting tasks as a percentage of the range of curvature, it is possible to observe when movements approach the bounds of this range of motion.

In this study, subjects were observed to have significantly more kyphotic lumbar curvature on extension than flexion during a lifting task. With lifting of a heavy object, the lumbar curvature was even more kyphotic. By moving to a highly kyphotic lumbar curvature during the extension phase of the lifting tasks, subjects appear to be approaching their limits of range of motion and may put greater tension on posterior spinal ligamentous structures and/or the extensor musculature.

The results of this study agree with previous studies of lumbar-pelvic coordination. Several authors reported that lumbar and pelvic motions occur almost simultaneously [Granata and Sanford, 2000, Dieen et al., 1996, Dieen et al., 1998, Burgess-Limerick et al., 1992]. The pattern of lumbar curvature remaining high for the extension phase of the lift agrees with previous studies that have shown the hip rotation preceding the lumbar rotation [Dieen et al., 1996, Dieen et al., 1998, Burgess-Limerick et al., 1992]. The current study builds on these studies by demonstrating that this pattern of hip rotation preceding lumbar rotation results in the lumbar curvature coming close to the edge of the in vivo lumbar range of motion.

These highly kyphotic postures relative to the range of lumbar curvature may be damaging to the ligaments, muscles and/or tendons. Solomonow et al. found that ligaments under tension exhibit a time-dependent response [Solomonow, 2004]. Solomonow et al. also found that mechanical and neuromotor disorders can result directly from creep, repetitive loading, and tension-relaxation of the ligamentous tissues [Solomonow, 2004]. Both the tendon and muscle may also be at greater risk of damage with repeated stretch-shortening cycles as might occur during repetitive lifting [Witvrouw et al. 2006, Butterfield and Herzog, 2006].

The elements at risk of injury may depend on which elements, ligaments or muscles dominate in limiting the range of motion. A number of studies have suggested, using models of lumbar motion to supplement experimental studies, that the ligaments of the spine do not contribute much to load support during a typical lift [Potvin et al., 1991, McGill et al., 1988, Adams and Dolan, 1991]. Potvin et al. [1991] argued that no more than 60 Nm of lifting moment comes from the spinal ligaments in most lifts. Adams and Dolan [1991] argued this is much lower at approximately 18 Nm during everyday tasks, well below the elastic limit measured in vitro of 33 Nm. Adams and Hutton [1986] further argued using cadaveric spine studies, that the spine in normal trunk flexion tasks is limited to 10 degrees from the elastic limit of the isolated spine. This previous literature, along with changes in the lumbar range observed with torso inclination, suggest that the musculature and tendons may be a strong component in limiting the lumbar curvature range and may be more at risk of damage. Passively, muscle provides stiffness that increases dramatically beyond the operating length of the muscle [McMahon, 1982]. With activation, muscle stiffness can increase further limiting the range of motion [McMahon, 1982, Morgan, 1977]. Further research examining the muscle lengths of the torso musculature and activation during lifting may serve to elucidate these roles.

This research raises the question, why are highly kyphotic postures assumed during the extension phase of lifting? Repeated stretching-shortening cycles have been demonstrated in a number of activities such as running, jumping, and flying to allow humans and animals to move very efficiently [Biewener, 2003, Ettema, 2001, Roberts, 2002, Gourgoulis, 2000]. In running and jumping, it has been hypothesize that the Achilles tendon and its associated muscle act as a powerful energy storage mechanism, storing energy as they are stretched and releasing that energy during shortening. Much like a spring, the tendon stiffness provides energy storage proportional to its stiffness. It is possible that subjects may be using similar elastic characteristics of their muscle and associated tendons in the trunk to “bounce”, taking advantage of the stored elastic energy to reduce muscle energy expenditure while raising the torso. While there may be energy advantages in such a strategy, it is possible that loads on these elastic structures may lead to injury. Therefore, further work is needed to investigate the energy expenditure as a function of lifting strategy and to investigate the relationship between the use of highly kyphotic postures during lifting tasks and risk of injury in industrial workers.

A few other studies have examined extreme lumbar curvatures although none have examined extremes of lumbar curvature in mid torso flexion postures or during dynamic lifting tasks. McGill et al. suggested that a fully flexed lumbar spine resulted in a transfer of load from muscle to passive tissues increasing the risk of injury to ligament in a study of extreme torso flexion [McGill et al., 2000]. Scannell and McGill examined low back joint loading and kinematics during standing and unsupported sitting and reported that sitting resulted in significantly more kyphotic postures than during standing [Scannell and McGill, 2003]. The authors suggested that standing may put less strain for the passive tissues [Scannell and McGill, 2003]. In addition, the authors demonstrated that the lumbar curvature assumed by subjects could be altered through training [Scannell and McGill, 2003]. The current study demonstrates that extreme lumbar curvatures may be also achieved during dynamic lifting tasks and in mid-range torso flexion postures.

The current study focuses on straight-leg lifts. With knee flexion, it is possible that both the lumbar curvature range and the pattern of hyper-kyphosis during extension may be altered. While no authors have examined the lumbar curvature range with knee flexion, a few have examined lifting tasks with knee flexion. McKean and Potvin [2001] found greater lumbar angles on extension relative to flexion during both freestyle and constrained lifts with knee flexion. However, Dieen et al [1996] demonstrated an greater phase lag (hip rotation before spine rotation in extension) with straight leg lifting relative to squat lifting. Further research is needed to examine these potential changes in lifting kinematics with knee flexion and how they are associated with the lumbar range.

In conclusion, a pattern of hyper-kyphosis during extension was observed in lumbar curvature for all lifting tasks. Subjects were found to move from a more neutral (in flexion) to a more kyphotic (in extension) lumbar curvature during lifting tasks, particularly while lifting heavier objects. This suggests increased involvement at extreme range of curvatures that may result in increased risk of injury. The subjects in this study were healthy, inexperienced, young adults. A future study might also examine experienced workers. If a kyphotic posture during lifting is a risk factor for low back injuries, experienced workers may be found to avoid the lifting patterns observed in inexperienced workers. Future studies should also be performed to see if subjects exhibiting pronounced kyphotic postures go on to exhibit a higher incidence of low back injury. Finally, future studies should examine the possibility of training subjects to avoid excessively kyphotic postures. Such training may be a method to reduce low back injury risk.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by Whitaker Foundation Biomedical Engineering Research (Grant RG-03-0043) and by the BRIN Program of the National Center for Research Resources (NIH Grant Number P20 RR16475).

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

Biographies

Anupama Maduri earned her M.S. in Mechanical Engineering from the University of Virginia in 2005. She is currently working the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health in Morgantown, West Virginia. Her research interests are in spine biomechanics and injury.

Bethany L. Pearson earned her B.S. in Mechanical Engineering from the University of Kansas in 2003. She is currently working for Burns and McDonnell in Kansas City, Missouri.

Sara E. Wilson earned a Ph.D. in Medical Engineering/ Medical Physics for Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1999. After post-doctoral work at the University of Virginia, Dr. Wilson joined the faculty at the University of Kansas as an Assistant Professor in Mechanical Engineering. Her research interests are in spine biomechanics and the neuromotor control of lumbar motion.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams MA, Hutton WC. Has the lumbar spine, a margin of safety in forward bending? Clin Biomechanics. 1986;1(1):3–6. doi: 10.1016/0268-0033(86)90028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams MA, Dolan P. A technique for quantifying the bending moment acting on the lumbar spine in vivo. J Biomechanics. 1991;24(2):117–126. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(91)90356-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biewener AA. Animal Locomotion. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess-Limerick R, Abernathy B, Neal RJ. Vertebral and hip movement occurs almost simultaneously during symmetric bimanual lifting movements. Spine. 1992 Sep;17(9):1122–1125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterfield TA, Herzog W. Effect of altering starting length and activation timing of muscle on fiber strain and muscle damage. J Appl Physiol. 2006;100:1489–1498. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00524.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieen JHv, Burg Pvd, Raaijmakers TAJ, Toussaint HM. Effects of Repetitive Lifting on Kinematics: Inadequeate Anticipatory Control or Adaptive Changes? J Motor Behavior. 1998;30(1):20–32. doi: 10.1080/00222899809601319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieen JHv, Toussaint HM, Maurice C, Mientjes M. Fatigue-Related Changes in the Coordination of Lifting and Their Effect on Low Back Load. J Motor Behavior. 1996;28(4):304–314. doi: 10.1080/00222895.1996.10544600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettema GJC. Muscle efficiency: the controversial role of elasticity and mechanical energy conversion in stretch-shortening cycles. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2001;85:457–465. doi: 10.1007/s004210100464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gade VK, Wilson SE. Variations in reposition sense in the lumbar spine with torso flexion and moment load; American Society of Mechanical Engineers Summer Bioengineering Conference; Key Biscayne, FL. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gracovetsky S. Potential of lumbodorsal fascia forces in generate back extension moment during squat lifts. J Biomed Eng. 1989;11:172–173. doi: 10.1016/0141-5425(89)90132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granata KP, Sanford AS. Lumbar-pelvic coordination is influence by lifting task parameters. Spine. 2000;25:1413–1418. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200006010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourgoulis V, Aggelousis N, Mavromatis G, Garas A. Three-dimensional kinematic analysis of the snatch of elite Greek weightlifters. J Sports Sci. 2000;18(8):643–652. doi: 10.1080/02640410050082332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalsa PS, Chiu JB, Aliberti N, Sileo M. Biomechanical evidence for proprioceptive function of lumbar facet joint capsule. 4th World Congress on Biomechanics; Calgary, CA. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lively MW. Sports medicine approach to low back pain. South Med J. 2002;95:642–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marras WS, Granata KP. Changes in trunk dynamics and spine loading during repeated trunk exertions. Spine. 1997;22:2564–2570. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199711010-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marras WS, Lavender SA, Leurgans SE, Fathallah FA, Ferguson SA, Allread WG, Rajulu SL. Biomechanical risk factors for occupationally related low back disorders. Ergonomics. 1995;38:377–410. doi: 10.1080/00140139508925111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKean CM, Potvin JR. Effects of a simulated industrial bin on lifting and lowering posture and trunk extensor muscle activity. Int J Industrial Ergonomics. 2001;28:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- McGill SM, Hughson RL, Parks K. Changes in lumbar lordosis modify the role of the extensor muscles. Clinical Biomechanics. 2000;15(10):777–780. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(00)00037-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill SM, Norman RW. Potential of lumbodoral fascia forces to generate back extension moments during squat lifts. J Biomed Eng. 1988;10:312–318. doi: 10.1016/0141-5425(88)90060-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon TA. Muscles, reflexes and locomotion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan DL. Separation of active and passive components of short-range stiffness of muscle. Am J Physiol. 1977;232(1):C45–C49. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1977.232.1.C45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachemson AL. Newest knowledge of low back pain; a critical look. Clin Orthop. 1992;579:8–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Work practices guide for manual lifting. NIOSH publication; Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) 1981:81–122.

- Olson MW, Li L, Solomonow M. Flexion-relaxation response to cyclic lumbar flexion. Clinical Biomechanics. 2004;19(8):769–776. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai S, Sundaram LJ. Low back pain: an economic assessment in the United States. Orthop Clin N Am. 2004;35:1–5. doi: 10.1016/S0030-5898(03)00101-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panjabi MM. The stabilizing system of the spine. Part I. Function, dysfunction, adaptation, and enhancement. J Spinal Disord. 1992a;5:383–389. doi: 10.1097/00002517-199212000-00001. discussion 397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panjabi MM. The stabilizing system of the spine. Part II. Neutral zone and instability hypothesis. J Spinal Disord. 1992b;5:390–396. doi: 10.1097/00002517-199212000-00002. discussion 397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panjabi MM. Clinical spinal instability and low back pain. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2003;13:371–379. doi: 10.1016/s1050-6411(03)00044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potvin JR, McGill SM, Norman RW. Trunk muscle and lumbar ligament contributions to dynamic lifts with varying degrees of trunk flexion. Spine. 1991;16(9):1099–1107. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199109000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punnett L, Fine LJ, Keyserling WM, Herrin GD, Chaffin DB. Back disorders and nonneutral trunk postures of automobile assembly workers. Scan j Work Environ Health. 1991;17:337–346. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts TJ. The integrated function of muscle and tendons during locomotion. Comp Biochem Physiol Part A. 2002;133:1087–1099. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(02)00244-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scannell JP, McGill SM. Lumbar posture - should it, and can it, be modified? A study of passive tissue stiffness and lumbar position during activities of daily living. Phys. Ther. 2003;83(10):907–917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomonow M. Ligaments: A source of work-related musculoskeletal disorders. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2004;14:49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomonow M, Zhou BH, Harris M, Lu Y, Baratta RV. The ligamento-muscular stabilizing system of the spine. Spine. 1998;23:2552–2562. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199812010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SE, Granata KP. Reposition sense of lumbar curvature with flexed and asymmetric lifting postures. Spine. 2003;28(5):513–518. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000048674.75474.C4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witvrouw E, Mahieu N, Roosen , McNair P. The role of stretching in tendon injuries. Br J Sports Med. 2007;133(4):1087–1099. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.034165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]