Abstract

Cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) gene VI encodes a multifunctional protein (P6) involved in the translation of viral RNA, the formation of inclusion bodies, and the determination of host range. Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Tsu-0 prevents the systemic spread of most CaMV isolates, including CM1841. However, CaMV isolate W260 overcomes this resistance. In this paper, the N-terminal 110 amino acids of P6 (termed D1) were identified as the resistance-breaking region. D1 also bound full-length P6. Furthermore, binding of W260 D1 to P6 induced higher β-galactosidase activity and better leucine-independent growth in the yeast two-hybrid system than its CM1841 counterpart. Thus, W260 may evade Tsu-0 resistance by mediating P6 self-association in a manner different from that of CM1841. Because Tsu-0 resistance prevents virus movement, interaction of P6 with P1 (CaMV movement protein) was investigated. Both yeast two-hybrid analyses and maltose-binding protein pull-down experiments show that P6 interacts with P1. Although neither half of P1 interacts with P6, the N-terminus of P6 binds P1. Interestingly, D1 by itself does not interact with P1, indicating that different portions of the P6 N-terminus are involved in different activities. The P1-P6 interactions suggest a role for P6 in virus transport, possibly by regulating P1 tubule formation or the assembly of movement complexes.

Keywords: CaMV, P6, TAV, P1, Arabidopsis, inclusion body protein

1. Introduction

Plant virus resistance is mediated at multiple levels including: elicitation of active defense responses involving programmed cell death (a hypersensitive response), elicitation of active defense responses without necrosis, and the degradation of viral RNAs by post-transcriptional gene silencing (Goodman and Novacky, 1994; Goodrick et al., 1991; Hull, 2002; Waterhouse et al., 1999). Although plant resistance can be effective in limiting viruses to the inoculated leaves or even individual cells, certain strains are able to infect even these protected hosts (Meshi et al., 1988; Meshi et al., 1989; Padgett and Beachy, 1993). Plant viruses may overcome resistance by a passive means, i.e., they are not recognized by the host. For example, passive resistance-breakage was observed in the relationship between specific Cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) isolates and Arabidopsis thaliana ecotypes (Agama et al., 2002). While certain A. thaliana ecotypes, such as Col-0, are susceptible to many isolates of CaMV others, such as Tsu-0, are resistant to many viral isolates, such as CM1841 (Balazs and Lebeurier, 1981; Leisner and Howell, 1992; Melcher, 1989). Tsu-0 resistance prevents systemic spread of CaMV, whereas isolate W260 evades detection by the Tsu-0 resistance machinery, which allows this CaMV strain to invade the host systemically (Agama et al., 2002). Analysis of chimeric DNA genomes generated from W260 and CM1841 localized the resistance-breaking determinant to the region of gene VI encoding the N-terminal 184 amino acid residues (termed RBR-1), of the protein product (P6).

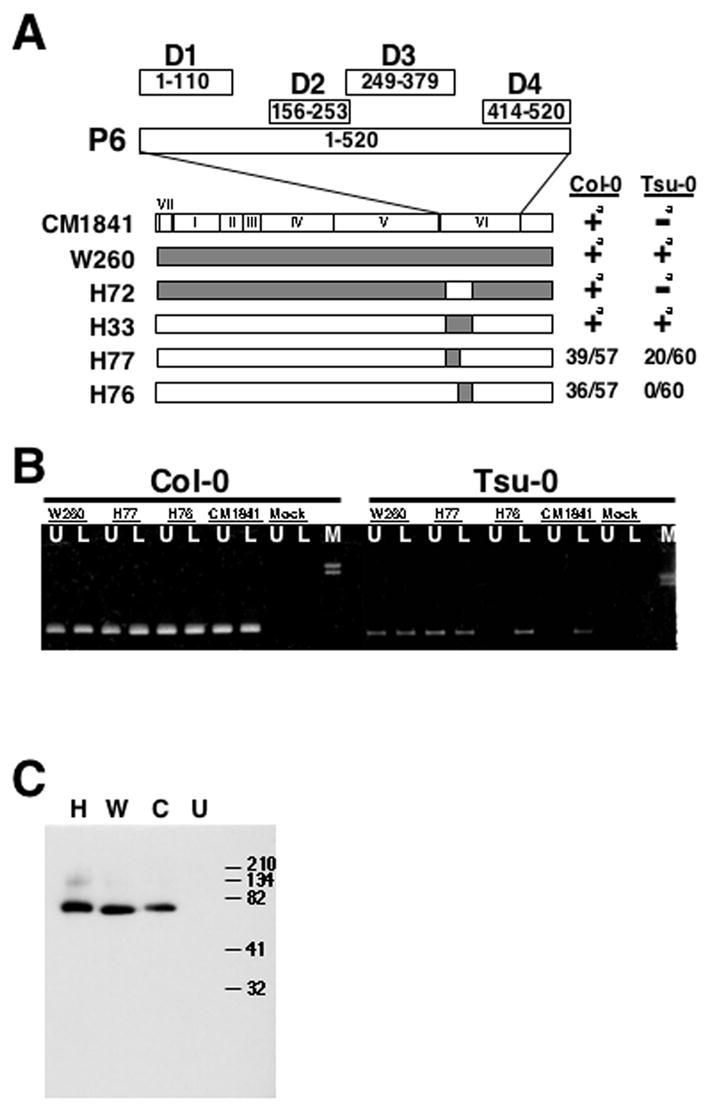

In addition to its role as a host range determinant, P6 is involved in many activities including regulating translation of viral proteins and forming the characteristic amorphous inclusion bodies observed in the cytoplasm of infected cells (Bonneville et al., 1989; Covey and Hull, 1981; De Tapia et al., 1993; Schoelz et al., 1986; Schoelz and Shepherd, 1988; Stratford and Covey, 1989). P6 specifically self-associates and this interaction is complex, involving at least 4 regions, termed domains, D1, D2, D3, and D4 (Fig. 1A) (Haas et al., 2005; Li and Leisner, 2002). Finally, P6 plays a role in virus movement. Transgenic plants expressing this protein facilitate the systemic spread of certain CaMV strains (Schoelz et al., 1991). Interestingly, like CaMV P6, potyviral inclusion body proteins have been implicated in virus cell-to-cell movement (Roberts et al., 1998).

Fig. 1.

The amino-terminal encoding 110 amino acids of gene VI contains a resistance-breaking determinant. (A) Cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) chimeras examined in this study. Portion above the CaMV genomic maps represents the 520 amino acid P6 protein; D1-D4 indicate the four domains involved in P6 self-association as described in (Li and Leisner, 2002) numbers in boxes indicate amino acid positions within P6. Below the schematic version of P6, the linearized versions of the CaMV genomic maps for the viral isolates and chimeras are shown as derived from (Schoelz and Shepherd, 1988; Wintermantel et al., 1993). Roman numerals indicate the locations of the various CaMV genes in the CM1841 (unshaded) and W260 (shaded) genomes. The 5’ to 3’ coding region of each gene is from left to right. The number of plants showing systemic symptoms out of the total number of plants inoculated is given to the right of the genome depictions. Note these numbers are from at least 3 experiments with 15-30 plants per experiment. aNumbers were previously reported in (Agama et al., 2002), these genomic maps are provided for reference. Note that the shaded region in the H77 chimera encodes domain D1 (amino acids 1-110). (B) Spread of CaMV chimeras through Arabidopsis ecotypes. Col-0 or Tsu-0 plants either mock-inoculated (UN) or inoculated with the CaMVs shown in A above, harvested 52 DPI and analyzed by PCR. Note: W260, H77, H76, and 1841 indicate the PCR products generated from plant tissue infected with those viruses, respectively. M, indicates lambda DNA digested with HindIII to serve as size markers, the 2.3 and 2.0 kbp fragments are shown. L indicates PCR product generated from rosette leaf tissue; U, from cauline leaf/flower stalk (inflorescence) portions of the plants. Arrow indicates the location of the 724 bp PCR product. (C) Western blot analysis of P6 from plant tissue infected with three CaMV isolates. Infected rosette leaf tissue from Col-0 plants inoculated with: H77, H; W260, W; CM1841, C; or mock-inoculated, U; was homogenized, protein extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE, blotted onto nitrocellulose, and probed with anti-P6 antibodies. The sizes, in kDa, of the protein markers are indicated to the left of the blot.

Virus movement is a requirement for efficient development of local and systemic infections within a host plant (Carrington et al., 1996; Hull, 2002; Nelson and van Bel, 1998). Although P6 has been suggested to play a role in movement, the CaMV protein identified as a movement protein is P1 (the gene I product), a 327 amino acid polypeptide that contains a central single-stranded nucleic acid binding domain (amino acids 101-177), as well as G (amino acids 128-130), D (amino acids 153-155) and LPL (amino acids 101-103) motifs characteristic of other movement proteins (Citovsky et al., 1991; Koonin et al., 1991; Linstead et al., 1988; Thomas and Maule, 1995a, b; Thomas and Maule, 1999; Thomas et al., 1993). P1 forms tubules through which CaMV particles presumably move from cell to cell (Huang et al., 2001; Linstead et al., 1988; Perbal et al., 1993; Thomas and Maule, 1995b). The N-terminal end of P1 is exposed on the external surface of the tubules, while the C-terminus lines the inside. The C-terminal end of P1 binds to the virion-associated protein, P3 (gene III product), which is exposed on the surface of CaMV particles (Stavolone et al., 2005). Hence, binding of P3 to P1 may explain how CaMV particles are loaded into tubules.

In this study, we further defined the CaMV resistance-breaking determinant to a specific portion of P6 and examined the role of this P6 region in self-association. Because resistance prevents viral spread, we also investigated whether P6 binds to the CaMV movement protein.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. A. thaliana ecotypes and virus inoculations

Seeds of A. thaliana ecotypes Tsu-0 and Col-0 were a gift from Dr. S. H. Howell (Plant Sciences Institute, Iowa State University, Ames, IA) and were planted in moistened Redi Earth potting soil (BFG Supply, Burton, OH). Plants were propagated in a growth chamber as described previously (Agama et al., 2002).

Cloned viral DNA for CaMV isolate CM1841 (pCaMV10) (Gardner et al., 1981) was provided by Dr. S. H. Howell. CaMV isolate W260 (Gracia and Shepherd, 1985), as well as the chimeric viruses CaMVH33 and CaMVH72 were reported previously (Schoelz and Shepherd, 1988; Wintermantel et al., 1993).

Chimeric viruses H76 and H77 were constructed by subcloning the 2335 bp SacI to BstEII DNA segments from CM1841 and W260 into pUCD9X (Close et al., 1984), which resulted in clones pCM-SB and pW260-SB, respectively. To generate H77, a 2052 bp EcoRI–BstEII segment of pW260-SB was replaced with the corresponding CM1841 sequence, and the resultant SacI – BstEII segment was exchanged with the SacI – BstEII segment of pCaMV10 (Gardner et al., 1981), a pBR322-based clone that contained an infectious copy of the CM1841 genome. To construct H76, the 213 bp EcoRI - PvuII segment of pCM-SB was replaced with the corresponding segment from W260, and the resulting SacI – BstEII DNA segment was exchanged with the SacI–BstEII segment of the pCaMV10. All CaMV isolates and chimeras were maintained in turnips (Brassica rapa cv. “Just Right”) by serial passage in a greenhouse at 22° C under natural lighting (Agama et al., 2002).

Arabidopsis thaliana ecotypes Col-0 and Tsu-0 at the six-leaf-stage were inoculated with sap prepared from symptomatic turnips and propagated following inoculation as described previously (Agama et al., 2002). Plants were observed daily for symptoms up to 52 days post-inoculation (DPI). Mock-inoculated plants were also included as controls. Each experiment was performed at least three times with 15-20 plants of each ecotype inoculated per experiment.

2.2. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) analyses of infected plants

All of the inoculated Tsu-0 or Col-0 plants from an individual pot (15-20 plants) were harvested at 52 DPI and rosette leaves were separated from cauline leaf/flower stalk tissue. The rosette leaves from all of the plants within each pot were pooled together. It is important to note that this pooled tissue included both inoculated and non-inoculated rosette leaves. Likewise, all of the cauline leaf/flower stalk tissue for each pot of plants was pooled. Mock-inoculated plant tissue was harvested and treated in the same way to serve as controls. Harvested tissue was ground, viral DNA was extracted, and PCR analyses were performed as described previously (Agama et al., 2002). A 724 base pair fragment spanning gene II (from nucleotide 1245-1969 (Gardner et al., 1981)) is generated by PCR and indicated the presence of the viral genomes. Each set of reactions was tested at least twice for each set of inoculated plants. All primers used for these analyses were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA).

2.3. Construction of clones for the protein binding assays

Plasmids pEG202 and pJG4-5, as well as yeast strain EGY48 harboring pSH18-34, were a gift from Dr. Roger Brent (Molecular Sciences Institute, Berkeley, CA). The plasmid pJG4-5, individually harboring either full-length CM1841 gene VI, gene VI lacking amino acids 250-379, or gene VI amino acids 106-253, as well as pEG202 expressing the CM1841 D1 region fused to LexA were described previously (Li and Leisner, 2002). The same full-length gene VI fragment was amplified by PCR using cloned CM1841 DNA as a template (pCaMV10; (Gardner et al., 1981)) with the FL-1F and FL-2R primers (Li and Leisner, 2002), the PCR product was cleaved with XhoI, filled in with DNA polymerase I Klenow fragment, and inserted, in the appropriate orientation, into the EcoRV site of Escherichia coli expression vector pG4-AB1 (Shenk et al., 2001) for pull-down analyses.

The CM1841 gene VI segment encoding the N-terminal 250 amino acids was generated by cleaving pJG4-5 harboring full-length gene VI with NcoI restriction endonuclease. The cohesive ends were subsequently filled in with DNA Polymerase I Klenow fragment and self-ligated. The cleavage, fill-in, and subsequent ligation disrupts the gene VI open reading frame creating a stop codon after amino acid 250.

The DNA fragment encoding the W260 P6 110 amino acid D1 fragment was amplified from pCaMVW260 (Gracia and Shepherd, 1985; Schoelz and Shepherd, 1988) by PCR as described previously for the CM1841 D1 fragment (Li and Leisner, 2002). The W260 and CM1841 D1s were also amplified with the primers FEL-1F and ECB-3R (Table 1) as above and inserted into the EcoRI and XhoI sites of pJG4-5.

Table 1.

Primers Used In This Work.

| Namea | Sequence (5’-3’)b | Locationc | Gene Amplifiedd |

|---|---|---|---|

| GI-1F | AATCTTCTGacTcGAGATGG | 343 | I |

| GI-F3 | CTGTATACtCgAGTTTGG | 902 | I |

| GI-R3 | AGGCTcgAGGTTTaGTTAAG | 962 | I |

| GI-2R | GTAATGCTCgagTTATTCTC | 1359 | I |

| FEL-1F | GACTGAGgAAtTCAGACCTC | 5749 | VI |

| FD-1F | CCAACTgAAtTcGCTATTCC | 5954 | VI |

| FD-2R | TGCTCgaGAATAGCCTaTAC | 5981 | VI |

| ECB-3R | CGTGGGcTcGAgTTCaCTG | 6120 | VI |

| KGL-1F | CCCAAAAGgGATCcCCTTTG | 6484 | VI |

Primers with the suffix ‘F’ are forward primers, while those with ‘R’ are reverse primers.

Sequence of primer, where the lower case nucleotides were changed from the CM1841 sequence (Gardner et al., 1981) and the restriction enzyme sites are underlined.

Nucleotide position of primer 5’ nucleotide on the CaMV genomic sequence.

CaMV gene amplified when using these primers.

The 5’ portion of D1 (termed D1a, encompassing P6 amino acids 1-64) was amplified as described above using the Fl-1F (Li and Leisner, 2002) and FD-2R primers (Table 1). This PCR fragment was digested with BamHI and XhoI and inserted into those sites of pEG202 (Ausubel et al., 1993; Gyuris et al., 1993). The 3’ portion of D1 (termed D1b, encompassing P6 amino acids 66-110) was amplified by PCR as above using the FD-1F (Table 1) and ECB-2R primers (Li and Leisner, 2002). This PCR product was cleaved with EcoRI and inserted into that site within pEG202.

The CM1841 gene VI segment coding for P6 amino acids 243-520 was amplified, using pCaMV10 as a template, with the KGL-1F (Table 1) and FL-2R (Li and Leisner, 2002) primers, cleaved, and inserted into the BamHI and XhoI sites of pEG202. The EcoRI and XhoI fragment encoding these amino acids was subsequently cleaved from this plasmid and inserted into those sites in pJG4-5.

The primers used to amplify the CaMV gene I fragments were designed to contain Xho I sites (Table 1). A full-length gene I fragment was generated by PCR using the GI-1F and GI-2R primers. The 5’ segment of gene I (encoding P1 amino acids 1-195), was amplified using the GI-1F and GI-R3 primers, while the 3’ segment (encoding P1 amino acids 185–327), was generated using the GI-F3 and GI-2R primers. The XhoI site engineered into the forward primer permitted in-frame fusion of the gene I fragment with the DNA sequence encoding either the LexA DNA-binding domain when inserted into the XhoI site of pEG202 or the Maltose Binding Protein (MBP) when inserted into the SalI site of pMAL-c2X (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). All gene I fragments were inserted into the XhoI site of pEG202.

A stop codon was introduced into pMAL-c2X to permit expression of maltose binding protein (MBP) as a non-fused protein, to serve as a control. This was accomplished by cleaving the plasmid with SalI and filling in the cohesive ends with DNA polymerase I Klenow Fragment. The plasmid was then self-ligated.

All DNA fragments were amplified with Pfu DNA polymerase and the template used for these constructions was either pCaMV10 (Gardner et al., 1981) or pCaMVW260 (Schoelz and Shepherd, 1988) where indicated. The standard program used for these amplifications contained an initial 2 min dwell at 94° C followed by 35 cycles of: a denaturation step of 94° C for 1 min, an annealing step of 55° C for 1 min, and an elongation step of 74° C for 3.5 min. Following amplification, the PCR reactions were phenol extracted and the products were collected by ethanol precipitation (Ausubel et al., 1993). PCR products were digested with the appropriate enzymes. The pEG202, pJG4-5, and pMAL-c2x plasmids were digested with the appropriate enzymes, followed by treatment with calf intestinal phosphatase. The PCR products were then inserted into the digested vectors using T4 DNA ligase, according to the manufacturer’s specifications. Ligation mixtures were then introduced into E. coli strain DH5α by calcium chloride transformation (Ausubel et al., 1993).

2.4. Yeast two-hybrid analyses

The recombinant pEG202 plasmids containing gene I or VI fragments were introduced into Saccharomyces cerevisiae EGY48, harboring the pSH18-34 β-galactosidase reporter plasmid, using a lithium acetate yeast transformation procedure (Ausubel et al., 1993; Gyuris et al., 1993). Yeast media was purchased from Clontech (Palo Alto, CA). Transformants were grown at 30° C and EGY48 lines, containing pSH18-34, were established harboring the pEG202 plasmid either with, or without (used as a control) an insert, were selected for on SD/-Ura-His medium.

Recombinant pJG4-5 plasmids harboring various gene VI fragments, or empty vector (used as a control), were introduced into these lines as above. The transformants were grown at 30° C on yeast plates containing either SD Base/Gal/Raf/-Ura-His-Trp (to test for transformation efficiency) or SD Base/Gal/Raf/-Ura-His-Trp-Leu (to test for protein interaction) (Clontech Laboratories, Palo Alto, CA). The β-galactosidase assays (Ausubel et al., 1993; Gyuris et al., 1993) were performed on a minimum of 3 independent yeast colonies as previously described (Li and Leisner, 2002).

To evaluate differences in growth rate, three independent colonies per yeast transformation expressing LexA DNA-binding domain fused to either the W260 or CM1841 D1s along with full-length P6 fused to the B42 transcription activation domain, were grown in leucine-deficient medium for 14 hours at 30° C and their optical density at 595 nm (OD595) was determined. To provide more quantitative data, representative yeast cultures were grown in leucine-deficient media to saturation and diluted to an OD595 of 0.6 with leucine-deficient media. Yeast cultures were then diluted 1:10, 1:50, 1:100, 1:200, 1:500, and 1:1000 with leucine-deficient media, 10 μl of each dilution was spotted onto leucine-deficient media plates and incubated for 72 hours at 30° C.

2.5. Protein Gel Electrophoresis

Liquid yeast cultures were grown in appropriate media and lysed using a glass bead method (Ausubel et al., 1993). Briefly, 2 ml of yeast were collected from a saturated culture by centrifugation for 2 min at 13,000×g in a microcentrifuge. Yeast pellets were resuspended in 250 μl of H2O and approximately 250 mg of glass beads (Sigma Corp., St. Louis, MO) were added to each sample, which were then vortexed for 2 min. Aliquots (100 μl) of each sample were removed to determine protein levels by performing a Bio-Rad Protein Micro-Assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The remainder of the supernatant was placed in a new tube along with 70 μl of 2X SDS electrophoresis buffer (SEB; 10 % β-mercaptoethanol, 0.02 % Bromophenol Blue, 20 % Glycerol, 4 % SDS, 125 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8). Samples containing equivalent amounts of protein were incubated at 100°C for 10 min, cooled on ice for 5 min and then loaded onto a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel.

To examine P6 expression in Arabidopsis, three symptomatic leaves from an infected plant were harvested and ground in 2 X SEB at 1 ml/gm tissue in a microcentrifuge tube. The soluble fraction was collected by centrifugation at 13,000×g for 5 min and the supernatant was transferred to a new microcentrifuge tube. Samples were then heated at 100°C and loaded onto a gel as above.

2.6. Western Blot Analyses

Proteins were separated by electrophoresis, at 14 V/cm, through polyacrylamide gels for approximately 1 hr in the Bio-Rad Mini Protean 3 System. Proteins were electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose at 30 volts for 16 hours at 4° C. The nitrocellulose filter was soaked for 2 hours at room temperature in Blocking Buffer (BB): TBST (20 mM Tris pH 7.6, 137 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20) containing 5% nonfat dry milk. The filter was incubated overnight at 4° C in BB containing primary antibody (1:300 dilution for anti-Lex A, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA; 1:400 for anti-P6 (Schoelz et al., 1991); or 1:500 for the anti-MBP, New England Biolabs, Ipswitch, MA; in 1X TBS (20 mM Tris pH 7.6, 137 mM NaCl), containing 0.05% Tween-20 with 5% non-fat dry milk). The filters were rinsed with TBST three times for 10 min each. BB containing secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (NA931V, Amersham Biosciences UK Limited) was added to the filters. Antibodies were diluted (1:600 for the anti-mouse for LexA or 1:800 for anti-rabbit antibodies for P6 and MBP) in 1X TBS, containing 0.05% Tween-20 with 5% non-fat dry milk. Blots were incubated for 2 hr at room temperature. The filters were rinsed with TBST three times for 10 minutes each, treated with HyGLO chemiluminescence developing solution (Denville Scientific, Inc., Metuchen, N.J.) and exposed to X-ray film, according to the manufacturer’s specifications. The film (HyBlot CL Autoradiography Film, Denville Scientific) was developed using a Konica SRX-101® developer.

2.7. Preparation of Bacterial Protein Extracts

A 5 ml culture of LBG+C (L-broth containing 11.1 mM glucose and 50 μg/ml carbenicillin) was inoculated with the appropriate bacterial culture and grown at 37° C overnight while shaking. These cultures were added to a 70 ml culture of LBG+C, and incubated at 37° C for 2 hours while shaking. Cultures were grown to an OD600 of 0.5, while those that grew past this point were diluted to the appropriate absorbance value with LBG+C. Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to the cultures to a final concentration of 333 μM, which were incubated at 37° C for 2 hr while shaking. Cultures were centifuged at 4000 × g for 10 minutes and pellets were resuspended in 10 ml of MBP column buffer (1 mM EDTA, 200 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4). Cells were lysed using a Fisher Scientific Model 100 Sonic Dismembranator, alternating pulsing on and off for 15 sec at a time, for a total of two min. Samples were periodically removed and analyzed by the Bradford Protein Assay (Bio-Rad Protein Assay Kit) to monitor protein liberation. Sonicated cell extracts were then cleared by centrifugation at 7000 × g for 25 min and supernatant (crude protein extract) was collected. Another 100 μl sample was removed to perform a Bradford Protein Assay to equilibrate levels of protein.

2.8. Maltose binding protein pull-down assays

One hundred μl of “bait” (MBP alone or fused to P1) crude protein extract was mixed in a microcentrifuge tube with 300 μl of “prey” (protein extract, from E. coli expressing P6 or containing empty expression vector) crude protein extract and incubated on ice for 2 hr. A tube identical to this mixture was also incubated concurrently, and was stored with 400 μl of 2X SEB as “Load.” The protein mixture was added to a tube containing 50 μl amylose resin solution equilibrated in column buffer (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) and incubated on ice for 90 min. The resin was collected by centrifugation for 3 min at 13,000×g in a desktop microcentrifuge, and the supernatant was collected and stored in 400 μl of 2X SEB as the “Flow-Through” fraction. The resin was washed with 1 ml of column buffer, collected by centrifugation at 13,000×g for 3 min in a desktop microcentrifuge, and the supernatant was discarded. Bound proteins were eluted by the addition of 200 μl of 10 mM maltose to the resin and incubation on ice for 2 hours. The resin was collected by centrifugation at 13,000×g for 3 min in a desktop microcentrifuge. The supernatant was collected and stored with 400 μl of 2X SEB as the “Elution.” The column samples were then separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blot analyses as described above.

3. Results

3.1. The Tsu-0 resistance-breaking determinant is located within the N-terminal 110 amino acids of P6

Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Tsu-0 is resistant to CaMV isolate CM1841 but susceptible to W260 and the RBR-1 coding region (amino acids 18-184) of gene VI is responsible for this difference (Agama et al., 2002; Leisner and Howell, 1992). To further localize the resistance-breaking determinant within RBR-1, two additional viral chimeras: H76 and H77 were tested (Fig. 1). These two chimeras consist of CM1841 genomes in which either the 5’ or 3’ half of the RBR-1 coding portion was replaced with that from W260. H77 contains the region of W260 gene VI encoding P6 amino acids 18-110, while H76 harbors the portion coding for residues 110-184. It is important to note that the sequence of the first 18 amino acids of W260 P6 is identical to that of CM1841 (Wintermantel et al., 1993). Turnips (data not shown) and Col-0 plants (tabulated in Fig. 1A) infected with either H76 or H77 showed systemic symptoms resembling those induced by CM1841. However, when the chimeras were inoculated to Tsu-0 plants, H77 induced systemic symptoms while H76 did not.

PCR analyses were performed to determine if the lack of symptoms induced by H76 was due to an inability of the virus to establish a systemic infection or to lack of symptom formation. The PCR analyses reflected the visible symptom data. As with both parental viruses, viral DNA could be detected in the rosette leaves and inflorescence of Col-0 plants infected with either H76 or H77 (Fig. 1B). In contrast, viral DNA of both chimeras and parents was detected in the rosette leaves of Tsu-0 plants but only H77 and W260 were detected in the inflorescences. This experiment further localized the resistance breaking determinant to the amino-terminal encoding 110 amino acids of gene VI.

The W260 P6 sequence contains a methionine at position 97 that the CM1841 counterpart does not possess (Wintermantel et al., 1993). Consequently, it is possible that W260 is able to avoid detection in Tsu-0 plants by internal translation initiation at methionine 97 instead of at the authentic start codon. This would result in a truncated protein lacking the N-terminal 96 amino acids. To eliminate this possibility, Col-0 leaf tissue was harvested from plants infected with W260, CM1841 and the chimera H77. Western blot analyses show that the H77 P6 is the same size as the CM1841 protein (Fig. 1C). In addition, H77 P6 from Tsu-0 plants is the same size as the protein in Col-0 (data not shown).

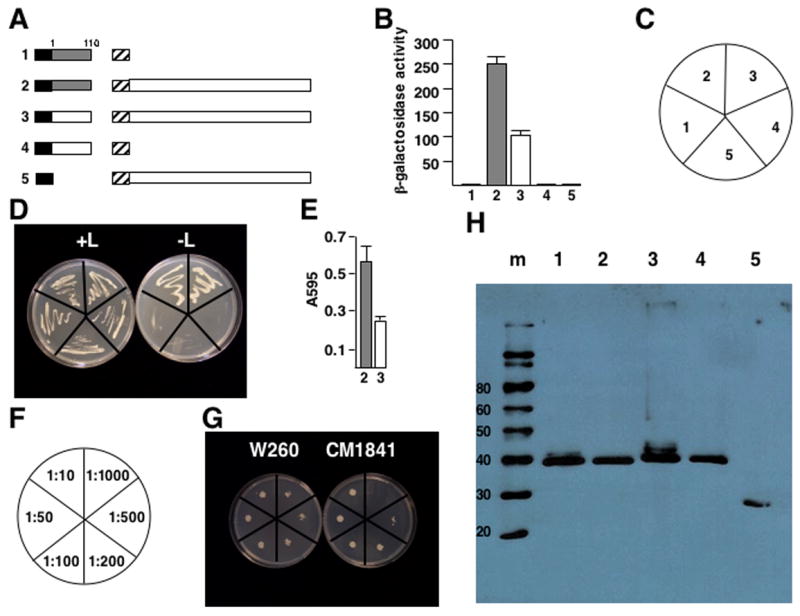

3.2. Domain D1s from resistance-breaking and non-breaking isolates show different binding in the yeast two-hybrid system

The amino-terminal 110 amino acids (termed domain D1) of P6 binds to the full-length protein (Haas et al., 2005; Li and Leisner, 2002) as well as containing the determinant responsible for resistance-breakage in A. thaliana ecotype Tsu-0. Therefore, we speculated that W260 domain D1 may bind differently to full-length P6 than the corresponding region of CM1841. To test this hypothesis, yeast two-hybrid analyses were performed (Fig. 2A). Both W260 and CM1841 D1s fused to LexA were found to interact with full length CM1841 P6 joined to the B42 transcription activation domain to permit leucine-independent growth of yeast transformants (Fig. 2C, D). However, the β-galactosidase activity of transformants expressing the W260 domain D1 was approximately 2.5-fold higher than for yeast expressing CM1841 D1 (Fig. 2B). Yeast expressing the D1 from W260 grew approximately twice as well in liquid cultures of leucine-deficient media as those expressing their CM1841 counterpart (Fig 2E). To examine the difference in growth in greater detail, a representative colony expressing either the W260 or CM1841 D1 was grown to the same OD600 in leucine-deficient liquid culture, diluted, and spotted on leucine-deficient media. Again, the W260 D1-expressing yeast grew at a higher dilution than those expressing the CM1841 counterpart (Fig. 2F, G). Western blot analyses indicated that W260 and CM1841 D1s were expressed to approximately equal levels (Fig 2H). However the LexA-D1 fusion proteins did not exhibit leucine-independent growth nor β-galactosidase activity when co-expressed with B42.

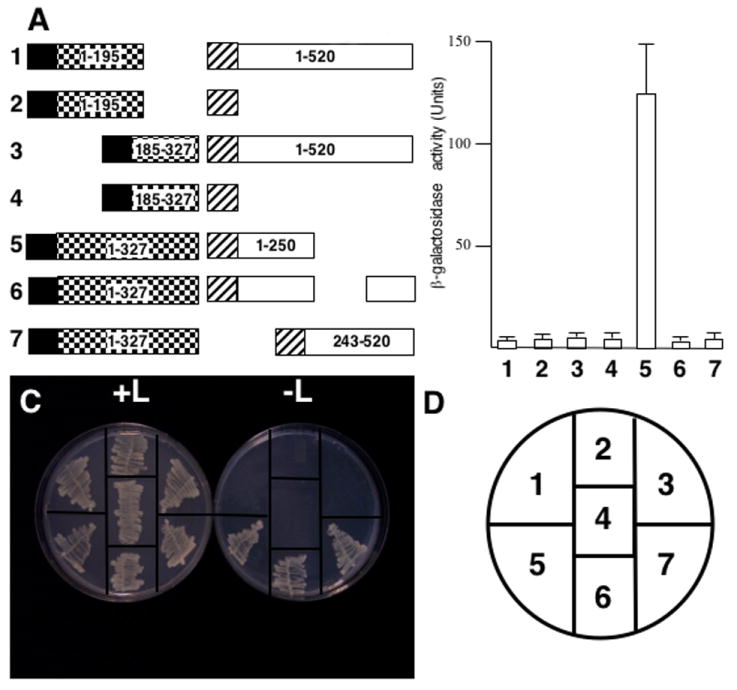

Fig. 2.

Binding of domain D1 to P6 differs between a resistance-breaking virus and one that does not overcome resistance. (A) Diagram of the constructions tested for leucine-independent growth and β-galactosidase activity. Note the constructions are not drawn to scale. Black box, LexA DNA-binding domain (from pEG202); hatched box, B42 transcription activation domain (from pJG4-5); shaded box, W260 P6 domain D1 (P6 amino acids 1-110). White box attached to LexA indicates CM1841 P6 domain D1; white box attached to B42, full-length CM1841 P6. Labels to the left of each pair of constructions correspond to the β-galactosidase assay data shown in B and the yeast colonies shown in D. (B) β-galactosidase activity of yeast transformants expressing constructions shown in A. Bar graph indicates average β-galactosidase units (on abscissa) for 3 experiments, along with the standard deviation. Shaded bars correspond to experiments employing W260 D1; white, CM1841 D1. Numbers at bottom (ordinate) correspond to the constructions shown in A and the transformants in D. (C) Key for the plates in D. (D) Growth of yeast transformants on media with (left, +L) and without (right, -L) leucine. The streaks are labeled (as shown in C) to correspond to the constructions shown in A and the β-galactosidase activities shown in B. (E) Growth of yeast transformants expressing W260 D1 (shaded) or CM1841 (white) along with the B42-P6 fusion proteins in leucine deficient media for 14 hours. Numbers below indicate the constructions shown in A. (F) Key for plates in G showing dilutions. (G) Growth of representative yeast colonies, expressing W260 D1 (left) or CM1841 D1 (right) along with full-length CM1841 P6, grown to saturation, diluted to A595 of 0.6, diluted as indicated in F and spotted onto leucine-deficient media. (H) Western blot analysis of protein levels expressed in yeast. The sizes of the molecular weight standards (m) are given on the left in kDa; numbers at top correspond to the constructions shown in A, the β-galactosidase activity in B, and the streaks shown in D.

The N-terminus of domain D1 (amino acids 1-64) contains an α-helix important for P6 self-association (Haas et al. 2005). To determine if differences in binding between the W260 and CM1841 D1s to P6 were associated with the α-helix, the D1 domains of CM1841 and W260 P6 were further divided into two segments, D1a (amino acids 1-64) and D1b (amino acids 65-110) that were inserted into the yeast two-hybrid vector pEG202 and examined for P6 interaction (Fig. 3A). Yeast transformants co-expressing either the CM1841 or W260 D1a along with P6 grew on leucine-deficient media (Fig. 3C, D) and showed β-galactosidase activity (Fig. 3B). However, the β-galactosidase activity generated from D1a regions of W260 and CM1841 binding to P6 was far more variable than that of D1 interaction with the same P6. W260 D1a binding to P6 is not significantly different from that of the CM1841 counterpart, even though the levels of expression for these domains were similar (Fig. 3E). Yeast transformants expressing either the CM1841 or W260 D1b along with P6 did not yield colonies capable of leucine-independent growth (Fig. 3C). Nor did colonies obtained on leucine-containing media show β-galactosidase activity, even though the D1b fusion proteins were expressed (Fig. 3B, E).

Fig. 3.

The N-terminal portion of domain D1 binds to P6 but the C-terminus does not. W260 and CM1841 P6 domain D1s were divided into two separate fragments D1a (amino acids 1-64) and D1b (amino acids 66-110) as indicated. (A) Diagram of the constructions tested for protein interaction. Note the constructions are not drawn to scale. Black box, LexA DNA-binding domain (from pEG202); hatched box, B42 transcription activation domain (from pJG4-5); shaded box, W260 P6 domain D1a (constructions 1 and 2) and D1b (constructions 5 and 6); white box, CM1841 P6 domain D1a (constructions 3 and 4) and D1b (constructions 7 and 8); white box attached to B42, full-length CM1841 P6. Labels to the left of each pair of constructions correspond to the β-galactosidase assay data shown in B and the yeast colonies shown in C. (B) β-galactosidase activity of yeast transformants expressing constructions shown in A. Bar graph indicates average β-galactosidase units (on abscissa) for 3 independent colonies, along with the standard deviation. Shaded bars correspond to experiments employing W260 D1 fragments; white, CM1841 D1 fragments. Labels at bottom (ordinate) correspond to the transformants grown on media with and without leucine in C. (C) Growth of yeast transformants on media with (left, +L) and without (right, -L) leucine. The streaks are labeled (as shown in D) to correspond to the constructions shown in A and the β-galactosidase activities shown in B. (D) Key for the plates in C. (E) Western blot analysis of protein levels expressed in yeast. The sizes of the molecular weight standards (m) are given on the left in kDa; arrows indicate the D1a and D1b fusion proteins; numbers at top correspond to the constructions shown in A, the β-galactosidase activity in B, and the streaks shown in C.

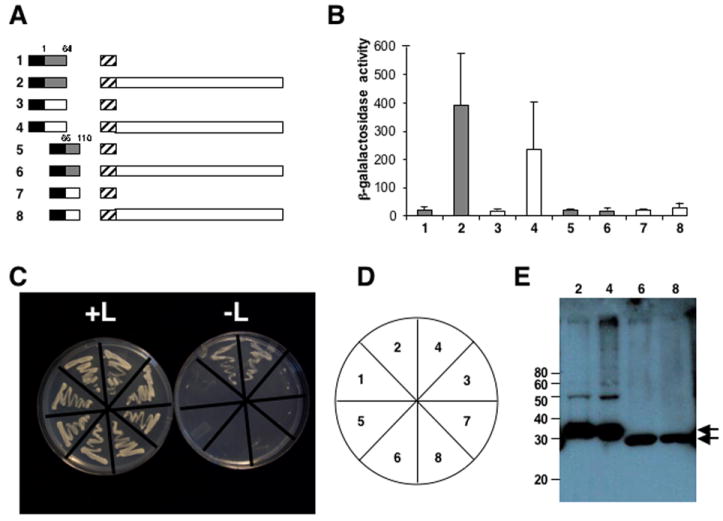

3.3. P6 interacts with P1

Tsu-0 resistance prevents CaMV movement (Agama et al., 2002) and P6 has been implicated in virus transport (Schoelz et al., 1991). The major CaMV movement protein is P1 (Linstead et al., 1988; Thomas and Maule 1995a, b; Thomas and Maule, 1999; Thomas et al., 1993). Therefore, the ability of P1 to interact with P6 was examined. Yeast expressing LexA-P1 from pEG202 were transformed with pJG4-5 expressing full-length B42-P6 (described in (Li and Leisner, 2002))(Fig. 4A). Yeast transformants co-expressing the LexA-P1 and B42-P6 fusion proteins grew on leucine-deficient media (Fig. 4C, D) and showed β-galactosidase activity (Fig. 4B). In contrast, yeast expressing the P1 LexA fusion proteins, with the B42 transcription activation domain alone, or the LexA DNA-binding domain alone, along with the B42-P6, did not grow on leucine-deficient media nor did they exhibit β-galactosidase activity.

Fig. 4.

P6 interacts with P1. (A) Diagram of constructions tested for interaction with the yeast two-hybrid system. Note the constructions are not drawn to scale. Black box, LexA DNA-binding domain (from pEG202); hatched box, B42 transcription activation domain (from pJG4-5); white box, full-length CM1841 P6 or fragments; checkerboard box, P1 (note, P1 is 327 amino acids long). Numbers inside constructions indicate amino acid positions for that polypeptide. Note, the portion of P6 deleted in experiment 6 spans amino acids 249-379. Constructions in numbers in bold to the left of each pair of constructions correspond to β-galactosidase assay data shown in B and yeast growth in C. (B) β-galactosidase activity of yeast transformants expressing constructions shown in A. The bar graph indicates average β-galactosidase activity (on abscissa) for 3 independent yeast colonies along with the standard deviation. Numbers at the bottom (ordinate) correspond to the constructions shown in A as well as the transformants grown on media with and without leucine in C. (C) Growth of yeast transformants on media with (left, +L) and without (right, -L) leucine. The streaks are numbered (key in D) to correspond to the constructions shown in A and the β-galactosidase activities shown in B. (D) Key for the plates in C. (E) Maltose binding protein pull-downs of P1 and P6. (E.a.) Approximately half of the P1-Maltose binding protein (P1-MBP) fusion binds to the amylose column and is eluted with maltose. (E.b.) Approximately half of the P6 added to the P1-Maltose binding protein (P1-MBP) fusion attached to the amylose column binds to the column and is eluted with maltose. (E.c.) P6 does not bind to MBP alone attached to the amylose column. (E.d.) P1-MBP attached to the amylose column does not bind to bacterial proteins that cross-react with P6 antibodies. Load; amount of protein initially loaded onto column; Flow-through, proteins that do not bind to the amylose column and are washed off; Elution, proteins eluting off the amylose resin. Note, panel E.a., was probed with anti-MBP antibodies, while panels E.b.-d were probed with anti-P6 antibodies.

To confirm the P1-P6 interaction biochemically, gene I was inserted into pMAL-c2X, full length gene VI was inserted into the expression vector pG4-AB1, and these constructs were expressed in E. coli. Bacterial extracts were generated and MBP pull-down assays were performed. Under our conditions, about half of the P1-MBP fusion protein bound to the amylose resin and was eluted when maltose was added (Fig. 4E, part a). Under these conditions, approximately half of the P6 added to the P1-MBP resin bound and was eluted when maltose was added (Fig. 4E, part b). None of the P6 added to an amylose resin expressing MBP alone attached to the resin (Fig. 4E, part c). Proteins cross-reacting with the P6 antibodies were not observed when extracts from bacterial cells containing empty expression vector (used to express P6) were added to amylose resin to which P1-MBP fusion protein was attached (Fig. 4E, part d). Taken togther, these data show that P6 attached to the P1-MBP fusion protein.

3.4. P6 N-terminus is involved in P1 binding

To further characterize the interactions of P1 with P6, the former protein was divided into two separate segments: an N- (amino acids 1-195) and a C-terminal region (amino acids 185–327) (Fig 5A). As with the negative controls, yeast transformants expressing either P1 segment fused to LexA with P6 fused to B42 did not grow on leucine-deficient media, nor did they show β-galactosidase activity (Fig. 5 B, C, D).

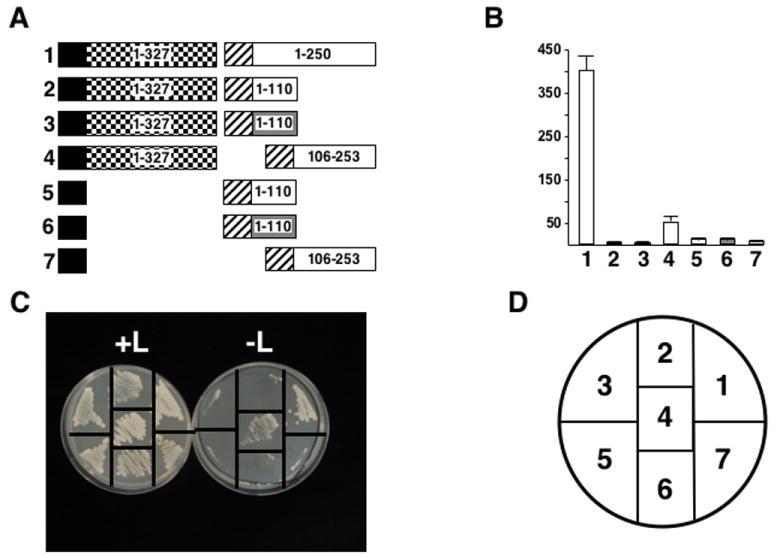

Fig. 5.

P6 N-terminus interacts with P1. (A) Diagram of constructions tested for interaction with the yeast two-hybrid system. Note the constructions are not drawn to scale. Black box, LexA DNA-binding domain (from pEG202); hatched box, B42 transcription activation domain (from pJG4-5); checkerboard box, P1; white box, P6. Numbers inside constructions indicate amino acid positions for that polypeptide. Note, the portion of P6 deleted in experiment 6 spans amino acids 249-379. Numbers in bold to the left of each pair of constructions correspond to β-galactosidase assay data shown in B and yeast growth in C. (B) β-galactosidase activity of yeast transformants expressing constructions shown in A. The bar graph indicates average β-galactosidase activity units (on abscissa) for 3 independent yeast colonies along with the standard deviation. Numbers at the bottom (ordinate) correspond to the constructions shown in A and the transformants grown on media with and without leucine in C. (C) Growth of yeast transformants on media with (left, +L) and without (right, -L) leucine. The streaks are numbered (key in D) to correspond to the constructions shown in A and the β-galactosidase activities shown in B. (D) Key for the plates in C.

We also examined the interaction of full length P1 with several deleted forms of P6 (Li and Leisner, 2002) (Fig. 5A). Yeast lines expressing LexA-P1 along with the P6 N-terminus (amino acids 1-250) fused to B42, yielded transformants capable of leucine-independent growth that also showed β-galactosidase activity (Fig. 5 B, C). A form of P6 lacking either the central portion (amino acids 250-379) of P6 (termed FL-ΔN, (Li and Leisner, 2002)) or the N-terminal 242 amino acids also yielded leucine-independent colonies when introduced into the LexA-P1 expressing yeast lines. However, these colonies showed no β-galactosidase activity above that of background. Yeast lines expressing any of the P6 deletions along with pEG202 with no P1 insert produced no colonies on leucine-deficient media (Fig. 4).

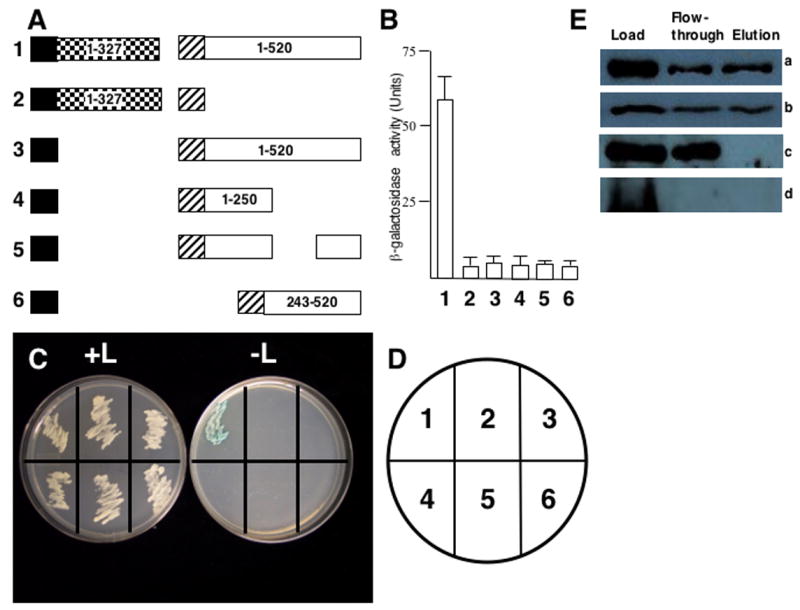

The N-terminal 250 amino acids of P6 that interact with P1 also include the resistance-breaking determinant. Therefore, the N-terminal 110 amino acids (D1) of W260 and CM1841 P6 were examined for P1 binding by yeast two-hybrid analysis (Fig. 6A). Yeast expressing either the W260 and CM1841 D1s along with P1 were incapable of leucine-independent growth and showed negligible β-galactosidase activity (Fig 6B, C). Likewise, yeast expressing the D1s with empty pEG202 did not grow on leucine-deficient media, nor did they possess β-galactosidase activity.

Fig. 6.

P1 does not interact with the Tsu-0 resistance-breaking determinant. (A) Diagram of constructions tested for interaction with the yeast two-hybrid system. Note the constructions are not drawn to scale. Black box, LexA DNA-binding domain (from pEG202); hatched box, B42 transcription activation domain (from pJG4-5); checkerboard box, P1; white box, fragments of CM1841 P6; shaded box, fragments of W260 P6. Numbers inside constructions indicate amino acid positions for that polypeptide. Numbers in bold to the left of each pair of constructions correspond to β-galactosidase assay data shown in B and yeast growth in C. (B) β-galactosidase activity of yeast transformants expressing constructions shown in A. The bar graph indicates average β-galactosidase activity units (on abscissa) for 3 independent yeast colonies along with the standard deviation. Numbers at the bottom (ordinate) correspond to the constructions in A and the transformants grown on media with and without leucine in C. (C) Growth of yeast transformants on media with (left, +L) and without (right, -L) leucine. The streaks are numbered (key in D) to correspond to the constructions shown in A and the β-galactosidase activities shown in B. (D) Key for the plates in C.

The data above implicated P6 amino acids 111-250 as being involved in P1 interaction. Hence, P6 amino acids 106-253 were examined for P1 interaction by yeast two-hybrid analysis (Fig. 6A). Yeast transformants expressing the P6 fragment showed leucine-independent growth and β-galactosidase activity (Fig. 6B, C). However, the β-galactosidase activity was not as strong as with the larger 250 amino acid fragment.

4. Discussion

Virus-host interactions are complex involving many different levels of defense and counter-defense (Hull, 2002). The ability of a host to recognize a virus and respond to it is critical for resistance. Prior work indicated that CaMV isolate CM1841 was targeted for resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Tsu-0, whereas W260 was able to evade the host surveillance system to systemically infect Tsu-0 plants (Agama et al., 2002). Furthermore, the W260 gene VI region encoding P6 amino acids 1-184 was responsible for overcoming resistance in A. thaliana ecotype Tsu-0. Interestingly, this region of W260 also contributes to its ability to evade plant defenses in solanaceous species (Wintermantel et al., 1993). In our work, the resistance-breaking region was further localized to the portion of W260 gene VI encoding the N-terminal 110 amino acids, termed domain D1 in binding studies (Li and Leisner, 2002). W260 domain D1 is sufficient to confer on CM1841, the ability to overcome resistance and to spread systemically through Tsu-0 plants.

In addition to its role in resistance breakage, domain D1 plays a role in P6 self-association as shown in yeast two-hybrid and pull-down studies (Haas et al., 2005; Li and Leisner, 2002). Therefore, the binding of the W260 and CM1841 domain D1s to the full-length CM1841 P6 protein was compared. While both D1s bound to the full-length protein, the capacity of the W260 D1 to bind to full-length P6 was stronger than the D1 sequence of CM1841. This difference in binding is evidence that sequence differences within the P6 protein regulate P6 inclusion body stability. In fact, Qiu et al. (1997) noted that the P6 inclusions formed by CM1841 were less stable than the P6 inclusions formed by W260, but they showed that the instability of CM1841 P6 inclusions could be traced to a point mutation in the P2 protein. This observation was puzzling, because the P2 protein is considered to form its own inclusion bodies that are distinct from the P6 inclusions (Espinoza et al., 1991). However, Givord et al. (1984) had also shown that the P2 protein influences P6 inclusion body stability. Consequently, it may be that the P2 protein is a minor constituent of the P6 inclusion, and that P6 inclusion stability is regulated both by sequences within P6, as well as by other proteins in the inclusion body such as the P2 protein (Qiu et al., 1997; Givord et al., 1984). Taken together with the work by Anderson et al., (1992), it would seem that the inclusion bodies formed by CM1841 and W260 P6s are of approximately equal stability. Thus, we believe it to be more likely, that W260 inclusion bodies are organized slightly differently from those of the CM1841 virus. Perhaps the binding of W260 P6 molecules together to form inclusion bodies prevents a determinant from being recognized by the Tsu-0 resistance machinery, but the CM1841 determinant remains unmasked permitting the virus to be detected by Tsu-0 plants. This would explain the ability of W260 to passively overcome Tsu-0 resistance (Agama et al., 2002).

The N-terminus of domain D1 contains an α-helix important for P6 self-association (Haas et al., 2005). Therefore, domain D1 for both of the W260 and CM1841 proteins was sub-divided into two parts that were subsequently examined for P6 binding. Domain D1 for both of the W260 and CM1841 proteins was sub-divided into two parts and examined for P6 binding. The D1a (the N-terminal portion containing the aforementioned α-helix) portion bound to P6 with approximately equal efficiencies for both W260 and CM1841. The D1a region of either the CM1841 or W260 proteins is capable of binding on its own, as previously shown (Haas et al., 2005). Binding of this region showed more variability than the intact domain D1. This is perhaps not surprising as the binding portion may need to be within a particular structural context, provided by an extended polypeptide fragment, to permit more efficient binding. In support of this idea, D1b (C-terminal portion of D1) for both CM1841 and W260 did not bind to P6. The fact that the D1a regions for CM1841 and W260 bound approximately equally well to P6 while the intact D1 regions did not, suggests that the D1b portion may aid binding by providing an appropriate structural context.

Tsu-0 prevents CaMV infection by inhibiting systemic movement (Agama et al., 2002). The CaMV genome encodes several proteins implicated in virus movement including P1, P3, and P6 (Kobayashi et al., 2002; Schoelz et al., 1991; Stavolone et al., 2005; Thomas et al., 1993; Turner et al., 1996). Interestingly, P6 was reported to help stabilize P1 in protoplasts (Kobayashi et al., 1998). In addition, P1 is found in inclusion bodies, the bulk of which is P6 (Covey and Hull, 1981; Reinke and deZoeten, 1991). Therefore, it was not a large surprise that a P1-P6 interaction was detected in our yeast two-hybrid and MBP pull-down analyses.

Even though full-length P1 interacted with P6, neither the N- nor C-terminal half of this protein did. This may suggest that the complete P1 protein is required to participate in these interactions. Alternatively, the portion of P1 involved in P6 interaction may be located at the junction of the N- and C-terminal fragments.

In contrast to P1, our data suggest that P6 can be sub-divided and specific portions can still interact with movement protein. The N-terminal 250 amino acids of P6 efficiently interact with P1. However, yeast expressing P1 and P6s lacking either the central portion or the N-terminus grew on leucine-deficient media but failed to exhibit β-galactosidase activity. Perhaps alone these P6 fragments bind less efficiently to P1 than the intact N-terminus, resulting in lower reporter gene activity.

While the P6 N-terminal 250 amino acids efficiently associated with P1, the first 110 amino acids of either W260 or CM1841 P6 (D1) did not. However, P6 amino acids 106-253 do interact directly with P1. Thus, different portions of P6 appear to be involved in resistance-breakage and P1 binding.

The function of the P6-P1 interaction is not known, although P6 likely assists P1 in some aspect of the movement process. CaMV proteins are translated in inclusion bodies (Reinke and deZoeten, 1991). While P1 can be detected in inclusion bodies, it is usually found at the periphery of the cell, where it forms tubules that project through plasmodesmata (Kasteel et al., 1996; Linstead et al., 1988; Thomas and Maule, 1999; Thomas and Maule, 1995b). Since tubules do not emanate from inclusion bodies, some factor must be present that prevents tubule formation before P1 reaches the periphery of the cell. That factor may be P6.

We speculate that P1 binds to P6 immediately after the former protein is synthesized on inclusion body ribosomes. Since inclusion bodies contain more P6 than P1, a complex between the two proteins could form. The plasmodesmatal targeting signal on P1 would permit the complex to be transported to the plasmodesmata, where the abundance of P1 may displace P6 and permit tubule formation. It is interesting to note that the N-terminal two-thirds of P1 are required for tubule formation (Thomas and Maule, 1999), while the intact protein appears to be required for P6 binding. Alternatively, P1-P6 interactions may help assemble movement complexes. The C-terminal proximal portion of P6 interacts with the CaMV capsid protein (P4) (Himmelbach et al., 1996; Ryabova et al., 2002) while the N-terminal proximal portion of P6 interacts with the movement protein as shown here. It is possible that P6 may bind both P1 and viral capsids at the same time, thereby bringing the two proteins close together. P1 could then be passed to P3 exposed on the surface of viral capsids (Stavolone et al., 2005) permitting the formation of a virion-P1 complex that could be targeted to plasmodesmata.

In summary, the work described here further illustrates the multifunctional nature of CaMV P6 protein. The N-terminal 110 amino acids of P6 are critical for viral recognition by Arabidopsis ecotype Tsu-0, the region just C-terminal to that interacts with the movement protein, and the rest of the protein is involved in other interactions. These interactions shed light on the mechanism(s) by which P6 mediates its many activities.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. S. H. Howell (Plant Sciences Institute, Iowa State University, Ames, IA) and Dr. R. Brent (Molecular Sciences Institute, Berkeley, CA) for the cloned genome of CaMV isolate CM1841; and for the yeast strains and plasmids for the two-hybrid system, respectively. The authors also thank Drs. Lirim Shemshedini, and Stephen Goldman (both at the University of Toledo), and the University of Toledo Plant Science Research Center, for their assistance. This work was supported in part by USDA grant number: 96-3503-3284; USDA ARS Specific Cooperative Agreement: 58-3607-1-193; NIH grant number: 1-R15-AI50641-01A1: The University of Toledo deARCE Memorial Endowment Fund In Support Of Medical Research And Development; and the Ohio Plant Biotechnology Consortium that was administered through the Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agama K, Beach S, Schoelz J, Leisner SM. the 5’ third of Cauliflower mosaic virus gene VI conditions resistance breakage in Arabidopsis ecotype Tsu-0. Phytopathology. 2002;92:190–196. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.2002.92.2.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson EJ, Trese AT, Sehgal OP, Schoelz JE. Characterization of a chimeric Cauliflower mosaic virus isolate that is more severe and accumulates to higher concentrations than either of the strains from which it was derived. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1992;5:48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Greene Publishing Associates and John Wiley & Sons, INC; Cambridge MA USA: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Balazs E, Lebeurier G. Arabidopsis is a host of cauliflower mosaic virus. Arabidopsis Inf Serv. 1981;18:130–134. [Google Scholar]

- Bonneville JM, Sanfacon H, Futterer J, Hohn T. Posttranscriptional transactivation in cauliflower mosaic virus. Cell. 1989;59:1135–1143. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90769-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrington JC, Kasschau KD, Mahajan SK, Schaad MC. Cell-to-cell and long-distance transport of viruses in plants. Plant Cell. 1996;8:1669–1681. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.10.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citovsky V, Knorr D, Zambryski P. Gene I, a potential cell-to-cell movement locus of cauliflower mosaic virus, encodes an RNA-binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:2476–2480. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Close TJ, Zaitlin D, Kado CI. Design and development of amplifiable broad-host-range cloning vectors: analysis of Agrobacterium tumefaciens plasmid pTiC58. Plasmid. 1984;12:1111–1118. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(84)90057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covey S, Hull R. Transcription of cauliflower mosaic virus DNA. Detection of transcripts, properties, and location of the gene encoding the virus inclusion body protein. Virology. 1981;111:463–474. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(81)90349-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Tapia M, Himmelbach A, Hohn T. Molecular dissection of the cauliflower mosaic virus translation transactivator. EMBO J. 1993;12:3305–3314. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06000.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza AM, Medina V, Hull R, Markham PG. Cauliflower mosaic virus gene II product forms distinct inclusion bodies in infected plant cells. Virology. 1991;185:337–344. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90781-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner RC, Howarth AJ, Hahn P, Brown-Luedi M, Shepherd RJ, Messing J. The complete nucleotide sequence of an infectious clone of cauliflower mosaic virus by M13mp7 shotgun sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 1981;9:2871–2888. doi: 10.1093/nar/9.12.2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Givord L, Xiong C, Giband M, Koenig I, Hohn T, Lebeurier G, Hirth L. A second cauliflower mosaic virus gene product influences the structure of the viral inclusion body. EMBO J. 1984;3:1423–1427. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb01987.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman RN, Novacky AJ. The hypersensitive reaction in plants to pathogens. APS Press; St. Paul, MN: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Goodrick BJ, Kuhn CW, Hussey RS. Restricted movement of cowpea chlorotic mottle virus in soybean with nonnecrotic resistance. Phytopathology. 1991;81:1426–1431. [Google Scholar]

- Gracia O, Shepherd RJ. Cauliflower mosaic virus in the nucleus of Nicotiana. Virology. 1985;146:141–145. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(85)90061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyuris J, Golemis E, Chertkov H, Brent R. Cdi1, a human G1 and S phase protein phosphatase that associates with Cdk2. Cell. 1993;75:791–803. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90498-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas M, Geldreich A, Bureau M, Dupuis L, Leh V, Vetter G, Kobayashi K, Hohn T, Ryabova L, Yot P, Keller M. The open reading frame VI product of Cauliflower mosaic virus is a nucleocytoplasmic protein: its N terminus mediates its nuclear export and formation of electron-dense viroplasms. Plant Cell. 2005;17:927–943. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.029017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himmelbach A, Chapdelaine Y, Hohn T. Interaction between cauliflower mosaic virus inclusion body protein and capsid protein: Implications for viral assembly. Virology. 1996;217:147–157. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z, Han Y, Howell S. Effects of movement protein mutations on the formation of tubules in plant protoplasts expressing a fusion between green fluorescent protein and Cauliflower mosaic virus movement protein. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2001;14:1026–1031. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2001.14.8.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull R. Matthews’ Plant Virology. fourth. Academic Press; San Diego: 2002. p. 1001. [Google Scholar]

- Kasteel DTJ, Perbal M-C, Boyer J-C, Wellink J, Goldbach RW, Maule AJ, van Lent JWM. The movement proteins of cowpea mosaic virus and cauliflower mosaic virus induce tubular structures in plant and insect cells. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:2857–2864. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-11-2857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K, Tsuge S, Nakayashiki H, Mise K, Furusawa I. Requirement of cauliflower mosaic virus open reading frame VI product for viral gene expression and multiplication in turnip protoplasts. Microbiol Immunol. 1998;42:377–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1998.tb02298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K, Tsuge S, Stavolone L, Hohn T. The Cauliflower mosaic virus virion-associated protein is dispensable for viral replication in single cells. J Virol. 2002;76:9457–9464. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.18.9457-9464.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koonin EV, Mushegian AR, Ryabov EV, Dolja VV. Diverse groups of plant RNA and DNA viruses share related movement proteins that may possess chaperone-like activity. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:2895–2903. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-12-2895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leisner SM, Howell SH. Symptom variation in different Arabidopsis thaliana ecotypes produced by cauliflower mosaic virus. Phytopathology. 1992;82:1042–1046. [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Leisner SM. Multiple domains within the Cauliflower mosaic virus gene VI product interact with the full-length protein. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2002;15:1050–1057. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2002.15.10.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linstead PJ, Hills GJ, Plaskitt KA, Wilson IG, Harker CL, Maule AJ. The subcellular location of the gene I product of cauliflower mosaic virus is consistent with a function associated with virus spread. J Gen Virol. 1988;69:1809–1818. [Google Scholar]

- Melcher U. Symptoms of cauliflower mosaic virus infection in Arabidopsis thaliana and turnip. Bot Gaz. 1989;150:139–147. [Google Scholar]

- Meshi T, Motoyoshi F, Adachi A, Watanabe Y, Takamatsu N, Okada Y. Two concomitant base substitutions in the putative replicase genes of tobacco mosaic virus confer the ability to overcome the effects of a tomato resistance gene, Tm-1. EMBO J. 1988;7:1575–1581. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02982.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meshi T, Motoyoshi F, Maeda T, Yoshiwoka S, Watanabe H, Okada Y. Mutations in the tobacco mosaic virus 30 kD protein gene overcome Tm-2 resistance in tomato. Plant Cell. 1989;1:515–522. doi: 10.1105/tpc.1.5.515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson RS, van Bel AJE. The mystery of virus trafficking into, through and out of vascular tissue. Prog Botany. 1998;59:476–533. [Google Scholar]

- Padgett HS, Beachy R. Analysis of a tobacco mosaic virus strain capable of overcoming N gene-mediated resistance. Plant Cell. 1993;5:577–586. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.5.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perbal M-C, Thomas CL, Maule AJ. Cauliflower mosaic virus gene I product (PI) forms tubular structures which extend from the surface of infected protoplasts. Virology. 1993;195:281–285. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu SG, Wintermantel WM, Sha Y, Schoelz JE. Light dependent systemic infection of solanaceous speices by cauliflower mosaic virus can be conditioned by a viral gene encoding an aphid transmission factor. Virology. 1997;227:180–188. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.8314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinke KJ, deZoeten GA. In situ localization of plant viral gene products. Phytopathology. 1991;81:1306–1314. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts IM, Wang D, Findlay K, Maule AJ. Ultrastructural and temporal observations of the potyvirus cylindrical inclusions (CIs) show that the CI protein acts transiently in aiding virus movement. Virology. 1998;245:173–181. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryabova LA, Pooggin MM, Hohn T. Viral strategies of translation initiation, ribosomal shunt and reinitiation. Prog Nucleic Acid Res. 2002;72:1–39. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6603(02)72066-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoelz J, Shepherd RJ, Daubert S. Region VI of cauliflower mosaic virus encodes a host range determinant. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:2632–2637. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.7.2632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoelz JE, Goldberg K-B, Kiernan J. Expression of cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) gene VI in transgenic Nicotiana biglovii complements a strain of CaMV defective in long-distance movement in nontransformed N. biglovii. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1991;4:350–355. [Google Scholar]

- Schoelz JE, Shepherd RJ. Host range control of cauliflower mosaic virus. Virology. 1988;162:30–37. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90391-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenk JL, Fisher CJ, Chen S-Y, Zhou X-F, Tillman K, Shemshedini L. p53 represses androgen-induced transactivation of prostate-specific antigen by disrupting hAR amino- to carboxyl-terminal interaction. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38472–38479. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103652200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stavolone L, Villani ME, Leclerc D, Hohn T. A coiled-coil interaction mediates cauliflower mosaic virus cell-to-cell movement. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:6219–6224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407731102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratford R, Covey S. Segregation of cauliflower mosaic virus symptom genetic determinants. Virology. 1989;172:451–459. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90187-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas CL, Maule AJ. Identification of the cauliflower mosaic virus movement protein RNA-binding domain. Virology. 1995a;206:1145–1149. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas TJ, Maule AJ. Identification of structural domains within the cauliflower mosaic virus movement protein by scanning deletion mutagenesis and epitope tagging. Plant Cell. 1995b;7:561–572. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.5.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas CL, Maule AJ. Identification of inhibitory mutants of Cauliflower mosaic virus movement protein function after expression in insect cells. J Virol. 1999;9:7886–7890. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.9.7886-7890.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas CL, Perbal C, Maule AJ. A mutation of cauliflower mosaic virus gene I interferes with virus movement but not virus replication. Virology. 1993;192:415–421. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner DS, McCallum DG, Covey SN. Roles of the 35S promoter and multiple overlapping domains in the pathogenicity of the pararetrovirus cauliflower mosaic virus. J Virol. 1996;70:5414–5421. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5414-5421.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse PM, Smith NA, Wang M-B. Virus resistance and gene silencing: killing the messenger. Trends Pl Sci. 1999;4:452–457. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(99)01493-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wintermantel WM, Anderson EJ, Schoelz JE. Identification of domains within gene VI of cauliflower mosaic virus that influence systemic infection of Nicotiana biglovii in a light-dependent manner. Virology. 1993;196:789–798. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(83)90001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]