Abstract

The primary goal of this study was to establish a rigorous approach for determining and comparing the NMR detection sensitivity of in vivo 31P MRS at different field strengths (B0). This was done by calculating the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) achieved within a unit sampling time at a given field strength. In vivo 31P spectra of human occipital lobe were acquired at 4 and 7 T under similar experimental conditions. They were used to measure the improvement of the human brain 31P MRS when the field strength increases from 4 to 7 T. The relaxation times and line widths of the phosphocreatine (PCr) resonance peak and the RF coil quality factors (Q) were also measured at these two field strengths. Their relative contributions to SNR at a given field strength were analyzed and discussed. The results show that in vivo 31P sensitivity was significantly improved at 7 T as compared with 4 T. Moreover, the line-width of the PCr resonance peak showed less than a linear increase with increased B0, which leads to a significant improvement in 31P spectral resolution. These findings indicate the advantage of high-field strength to improve in vivo 31P MRS quality in both sensitivity and spectral resolution. This advantage should improve the reliability and applicability of in vivo 31P MRS in studying high-energy phosphate metabolism, phospholipid metabolism and cerebral biogenetics in the human at both normal and diseased states noninvasively. Finally, the approach used in this study for calculating in vivo 31P MRS sensitivity provides a general tool in estimating the relative NMR detection sensitivity for any nuclear spin at a given field strength.

Keywords: In vivo 31P MRS, Human brain, High field, NMR sensitivity, Spectral resolution

1. Introduction

In vivo 31P MRS allows noninvasive assessment of many fundamental biochemical, physiological and metabolic events occurring inside living brains (e.g., [1–4]). The prime information provided by in vivo 31P MRS includes intracellular pH, intracellular free magnesium concentration ([Mg2+]) and high-energy phosphate (HEP) metabolites such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP), phosphocreatine (PCr) and inorganic phosphate (Pi). These HEP metabolites are tightly linked to brain metabolism and bioenergetics through regulating the biochemical energy production (i.e., ATP synthesis) and consumption (i.e., ATP utilization). Besides the HEP metabolites, other detectable phosphate compounds in the human brain include uridine diphospho sugar (an important precursor for glycogen metabolism) [3], nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP) involving oxidative chains and several important phosphate compounds that are actively involved in membrane phospholipid metabolism [5]. The steady-state phosphate metabolite signals and other physiological parameters detected by in vivo 31P MRS have been used extensively in clinical studies. The abnormality of the phosphate signals has been linked to numerous diseases, such as brain ischemia and seizure [6,7], epilepsy [4,8], Alzheimer disease [9] and schizophrenia [10]. Moreover, the use of in vivo 31P MRS combined with the magnetization transfer approach can measure the kinetics of biochemical reaction rate and enzyme activity noninvasively [11–14]. These measurements should be vital in studying cerebral bioenergetics related to brain function and brain disorder.

However, the capability of in vivo 31P MRS for biomedical applications is often limited, especially at relatively low fields, due to the following challenges: (a) low intrinsic sensitivity because of its relatively low magnetogyric ratio (γ), (b) low NMR detectable concentrations of phosphate compounds (in the range of few millimolars), (c) overlap of adjacent resonance peaks from different phosphate compounds (e.g., in chemical shift range near the Pi resonance peak) and (d) relatively low spatial resolution that can be achieved by in vivo 31P MRS or spectroscopic imaging. Therefore, the applicability and reliability of in vivo 31P MRS approaches rely on one key aspect, that is, NMR detection sensitivity and spectral resolution.

One efficient approach to improve the NMR sensitivity of in vivo MRS is to increase magnetic field strength (B0). The field strength for human MRI/MRS research has been increased rapidly from 3–4 to 7–9.4 T. The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of in vivo 1H MRS is significantly increased at high/ultrahigh fields (e.g., [15–17]). It was demonstrated that both the SNR and quality of 31P MRS acquired in the human brain are improved at 2 and 4 T compared with 1.5 T [18–20]. We have recently qualitatively illustrated that the in vivo 31P MRS acquired from the human occipital lobe was further improved at 7 T [3]. One interesting and essential question is how much can in vivo 31P MRS benefit at 7 T compared with 4 T for human applications? Addressing this question requires a sophisticated and quantitative approach to precisely determine the SNRs attainable at different field strengths. In general, there are different strategies for quantifying SNR in in vivo MRS. One approach is to determine the SNR of a spectrum collected with single acquisition at fully relaxed condition. However, such SNR measurement may not be very useful because most in vivo MR studies are conducted at partially saturated condition by using a much shorter repetition time (TR) in comparison with five times of longitudinal relaxation time (T1). This allows signal averaging within limited sampling time to gain SNR. Therefore, it is essential to determine the SNR of NMR signal acquired within a unit sampling time. This SNR value is determined not only by the magnetic field strength but also by many other NMR parameters, such as T1, apparent transverse relaxation time (T2*) and RF coil quality factor (Q), which are all field dependent. All of these parameters should be measured and accounted for at different field strengths. However, most SNR comparison studies reported in the literature were conducted using the same NMR acquisition parameters at different field strengths, which did not accounts for the influence of these field-dependent parameters upon the SNR measurement at a given field strength. The conclusions draw from these studies would be subjective to the specific NMR parameters used in the SNR measurements. In this work, we have applied a comprehensive approach to quantitatively determine and compare the in vivo 31P NMR sensitivity obtained in the human brain at 4 and 7 T with the same NMR methodology and similar experimental setup. The PCr resonance peak in the in vivo 31P MRS was used for the quantification and comparisons.

2. Theory

Under optimal condition, which means that the pulse flip angle (α) satisfies the Ernst equation of cos(αopt)= exp(−TR/T1) [21], the SNR of NMR resonance peak in a spectrum acquired with the single-pulse-acquisition pulse sequence in a given unit sampling time can be expressed as [21,22]

SNR (per unit sampling time) ∝

| (1) |

where , C is the concentration of the nuclear spin under observation and at is the NMR spectrum acquisition time. C and γshould be the same at 4 and 7 T for the same nuclear spin, and they can be treated as a constant. Since T2*=1/(πΔν1/2), where Δν1/2 is the line width of the resonance peak of interest, Eq. (1) can be rewritten as SNR (per unit sampling time) ∝

| (2) |

This equation accounts for most field-dependent parameters that have influences in the net SNR, such as T2* signal loss and partial saturation of NMR signal due to relatively short TR. To precisely quantify and understand the NMR sensitivity as a function of magnetic field strength, one needs to experimentally determine and quantify all parameters used in Eq. (2). Notice that the definition of SNR as used in this article was based on the description of Eq. (2).

We have conducted a comprehensive 31P MRS study to compare the sensitivity and spectral resolution of PCr resonance peak in the human occipital lobe at 4 and 7 T. The results from this study answered the following questions: (a) How much SNR gain can be achieved in the human brain in vivo 31P MRS at 7 T as compared with 4 T? (ii) How do the measured NMR parameters contribute to the SNR gain at different field strengths?

3. Methods and materials

Twelve healthy human adults (eight men and four women, 19–50 years old) were recruited for this study; six of them performed the SNR comparison study at 4 and 7 T, and the other six performed the study of T1 measurements at 4 T. The experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Minnesota, and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects prior to study.

The experiments were performed at 4-T (Oxford 90-cm bore magnet) and 7-T (Magnex Scientific 90-cm bore magnet) whole-body MR scanners interfaced with the same Varian console (Varian, Palo Alto, CA). Two passively decoupled dual-coil RF probes with the identical head holder and coil geometry were designed and constructed for both 4- and 7-T experiments. Each RF probe includes (a) a linear and large butterfly 1H surface coil for shimming and acquiring anatomical images using the T1-weighted Turbo-FLASH imaging sequence and (b) a 5-cm-diameter single-loop 31P surface coil, designed for covering the human occipital lobe, for acquiring in vivo 31P spectra. The noise figure of the receiver preamplifier of the spectrometer was 1.1 dB at 4 T and 1.3 dB at 7 T, resulting in a negligible difference in the preamplifier noise (~2%) for the 31P spectral measurements.

The same subjects were examined at both 4 and 7 T with the similar experimental setup. The subject’s head position relative to the RF probes was carefully controlled to ensure that the 31P spectra acquired at the two fields were sampled from the same brain region of the subject. The RF power for achieving a nominal 90° flip angle for in vivo 31P MRS acquisition was experimentally calibrated, and the RF power was optimized and scaled down to give an Ernst angle according to the Ernst equation using a fixed repetition time (TR=3 s) and the T1 value of PCr at given field strength. The single-pulse-acquisition sequence (α-acquisition using a 200-μs hard pulse) was applied to acquire in vivo 31P spectra from the human occipital lobe. Other spectral parameters were: spectral width=5000 Hz and spectrum acquisition time (at)=0.1 s.

T1 was measured at near fully relaxed condition with TR=16 s (≈4T1). Inversion recovery pulse sequence (180°-TI-α-acquisition, where TI is the inversion recovery time) was used to determine the T1 values of PCr at 4 T [3]. The magnetization inversion of the PCr and other resonance peaks was achieved adiabatically in the entire sensitive volume of the 31P RF surface coil by using a B1-insensitive, 16-ms hyperbolic secant RF pulse [23]. A total of eight measurements with different TI values ranging from 12.5 ms to 32 s were performed to calculate the PCr T1 value. No additional spatial localization was applied, except that achieved by the surface coil itself to ensure that the major 31P NMR signal detected by the coil is confined in the human occipital lobe [3]. A simulation program developed by Varian was utilized to fit and calculate T1 values based on the following equation:

| (3) |

where M(TI) is the longitudinal magnetization at time TI and M(0) and M0 are the longitudinal magnetizations at TI=0 and at equilibrium, respectively.

An optimal line broadening that is equal to the line width of the PCr resonance peak (9.0 Hz at 4 T and 13.4 Hz at 7 T) was applied to spectral data processing for SNR enhancement and for improving quantification accuracy. The PCr peak height was used for quantification in the T1 regression according to Eq. (3). The SNR values were calculated by obtaining the ratio of the PCr peak height to the peak-to-peak spectral noise and multiplying it by 2.5.

4. Results

Fig. 1 shows the 2D 31P chemical shift image (CSI) of a cylindrical bottle phantom (7 cm diameter) filled with high-concentration Pi at 4 T (Fig. 1A) and 7 T (Fig. 1B). The CSIs were acquired by using the similar RF surface coils and nominal 90° flip angle under fully relaxed condition at these two fields. The Fourier-series window technique was applied to obtain the 2D CSIs [24]. The 1D profiles of Pi signal along two orthogonal dimensions are similar between 4 and 7 T, which indicates that the sample regions and NMR signal distributions detected by the surface coils at these two fields are equivalent. Thus, it was valid to conduct the SNR comparison study between 4 and 7 T using the experimental protocol.

Fig. 1.

2D 31P CSI in the transversal orientation and its 1D profiles in two dimensions acquired at (A) 4 T and (B) 7 T using a cylindrical bottle phantom filled with high-concentration Pi. The field of view was 10×10 cm, and the phase-encoding steps were nine in each dimension.

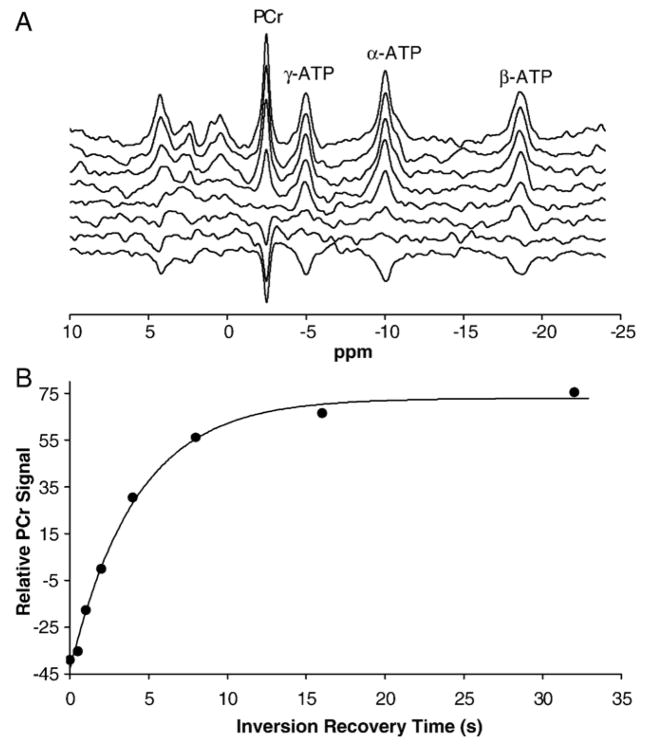

Fig. 2 demonstrates the T1 measurement of PCr resonance peak in the human occipital lobe at 4 T. The T1 recovery was fitted by a single exponential curve (see Fig. 2B) according to Eq. (3). The averaged PCr T1 value in the human occipital lobe at 4 T was 4.27±0.27 s (n =6). In contrast, the PCr T1 value at 7 T measured 3.37±0.29 s [3].

Fig. 2.

31P T1 relaxation time measurement for PCr peak from a representative human occipital lobe at 4 T. (A) Inversion recovered in vivo 31P spectra acquired from one representative subject. Eight TI values were measured. (B) Exponential fitting of the PCr signal as a function of TI for calculating the PCr T1 value (4.20 s).

Fig. 3A shows a sagittal image covering the human occipital lobe and the position of the 31P surface coil. Fig. 3B and C illustrates in vivo 31P spectra acquired with 128 signal averages (TR=3 s) at 4 and 7 T, respectively, from the same subject as shown in Fig. 3A. They show improvements of in vivo 31P spectrum quality in both sensitivity and spectral resolution at 7 T.

Fig. 3.

(A) Anatomical human brain MRI (in the sagittal orientation). In vivo 31P spectra acquired from the human occipital lobe at (B) 4 T and (C) 7 T using the same experimental setup and NMR acquisition parameters (TR=3 s and 128 signal averages). PE, phosphoethanolamine; PC, phosphocholine; Pi, inorganic phosphate; GPE, glycerophosphoethanolamine; GPC, glycerophosphocholine; PCr, phosphocreatine; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; NADP, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate.

Table 1 summarizes the results of the PCr T1 relaxation times, line widths (Δν1/2) and SNRs, as well as RF coil quality factors, measured at 4 and 7 T. Importantly, there is a 56% increase in SNR of the PCr resonance peak at 7 T as compared with 4 T.

Table 1.

Summary of relaxation times, line widths and SNRs of PCr, as well as RF coil quality factors, at 4 and 7 T

| B0 | T1 (s), n =6 | Δν1/2 (Hz), n =6 | Q | SNR, n =6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 T | 3.37±0.29* | 13.4±0.8* | 79.5 | 81.4±7.2* |

| 4 T | 4.27±0.27 | 9.0±0.4 | 130 | 52.2±8.4 |

| Ratio | 0.79 | 1.49 | 0.61 | 1.56 |

The measured parameter at 7 T is significantly different from 4 T (P<0.05).

Fig. 4 illustrates the relationship between the PCr T1 value and magnetic field strength. Data used in this figure came from both the literature and our results measured in this study and a previous study [3].

Fig. 4.

Field dependence of PCr T1 in the human brain. The data were based on the literature (circle), which were summarized in Ref. [3], and on the measurements from our laboratory (dot).

5. Discussion and conclusion

The G(TR/T1) term in Eq. (2) is close to unity when TR<T1. In this study, TR was 3 s at both 4 and 7 T and T1 was 4.27 s at 4 T and 3.37 s at 7 T; thus, the G(TR/T1) term was equal to 0.98 at 4 T and 0.97 at 7 T accordingly (see Table 2). Under this condition, the function G(TR/T1) was very similar and close to 1 at the two fields. In addition, the acquisition time parameter (at) was 0.1 s at both fields, T2* was 35 ms at 4 T and 24 ms at 7 T, and the function in Eq. (2) was approximately equal to 1.00 at both 4 and 7 T (see Table 3). With these facts, we can simplify Eq. (2), which further leads to the following approximate equation: SNR (per unit sampling time) ∝

Table 2.

Values of the function G(TR/T1) at 4 and 7 T

| B0 | TR (s) | T1 (s) | TR/T1 | G(TR/T1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 T | 3.0 | 3.37 | 0.89 | 0.97 |

| 4 T | 3.0 | 4.27 | 0.70 | 0.98 |

Table 3.

Values of the function at 4 and 7 T

| B0 | at (s) | Δν1/2 | (Hz) | T2* (ms) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 T | 0.1 | 13.4 | 24 | 1.00 | ||

| 4 T | 0.1 | 9.0 | 35 | 1.00 |

| (4) |

Inserting all measured parameters as summarized in Table 1 into Eq. (4) at both 4 T and 7 T, we deduced β to be 1.4, which is in excellent agreement with the theoretically predicted β value of 1.5 as described in the literature [21,22,25].

Comparing the T1 data obtained in this study with those previously reported in the literature (see the summarized results as cited in Ref. [3]), we found that the T1 relaxation time of PCr in the human brain does not change significantly between 1.5 and 7 T (P>0.05; also see Fig. 4) based on the entire pool of T1 data. However, the results of T1 measurements in the human brain obtained in our laboratory reveal a significant decrease at 7 T [3] as compared with 4 T (dropping 21%, see Table 1). This observation indicates that the field dependence of PCr T1 is presumably determined by two competing relaxation mechanisms, that is, chemical shift anisotropy (CSA) and dipolar interaction, which simultaneously influence the 31P relaxation times [26,27]. In the case with dominant CSA contribution, the T1 value should decrease with increasing field strength following the relation: 1/(T1) α B0 2, while in the case of dominant dipolar interaction contribution, the T1 value usually increases with increasing field strength (e.g., for in vivo 1H MRI/MRS). The opposite trends between these two relaxation mechanisms could lead to an approximately field independence of PCr T1 and/or a decrease in PCr T1 at higher field as observed in our study. This observation was supported by the rat study showing that the T1 values of brain phosphorus metabolites decreased with increasing field strength [26]. The decrease in the T1 values at higher field strength offers an advantage for in vivo 31P MRS because a shorter TR can be employed to allow more signal averaging within the same sampling time and, ultimately, to increase SNR. According to Eqs. (4) and (5) (see the third term on the right side of Eq. (5)), the decrease in the PCr T1 at 7 T alone could contribute a 13% SNR gain at 7 T as compared with 4 T.

| (5) |

The average line width of PCr (without line broadening) observed in this study was 13.4±0.8 Hz at 7 T and 9±0.4 Hz at 4 T. As illustrated by the fourth term on the right side of Eq. (5), this line-width broadening alone can lead to an 18% loss in SNR at 7 T as compared with 4 T. However, the ratio of these two line widths is 1.49, which is smaller than the ratio of field strengths between 4 and 7 T (1.75). This observation indicates that the line-width broadening of the PCr resonance peak with increased field strength was not linearly correlated to the field strength and it was smaller than the magnitude of field strength increase. Moreover, the chemical shift dispersion (i.e., in hertz) of in vivo 31P MRS increases linearly with field strength. The combination of these two facts (i.e., large increase in chemical shift dispersion and relatively small increase in line-width broadening) improves the 31P spectral resolution at 7 T as demonstrated in Fig. 3. This improvement makes it possible to resolve many adjacent phosphorus resonance peaks (e.g., α-ATP vs. NADP) and other phosphate compounds involved in phospholipid metabolism (e.g., glycerophosphocholine vs. glycerophosphoethanolamine and phosphocholine vs. phosphoethanolamine), as shown in Fig. 3. Therefore, the advantages of 7 T should improve accuracy and reliability for quantifying the phosphorus compounds.

The field dependence of NMR detection sensitivity is significantly distinct among different nuclei. It has been shown that the average SNR increases linearly from 4 to 7 T for the proton imaging of human brain [28]. In contrast, as demonstrated in the rat brain [29], there is an approximate quadruple increase in SNR for in vivo 17O MRS from 4.7 to 9.4 T without significant changes of 17O T1 and T2 relaxation times of water. For the in vivo 31P MRS of human brain, the SNR acquired within a unit sampling time gains 56% at 7 T as compared with 4 T, based on our measurements, when the field strength increases 75% from 4 to 7 T. Besides a shortened T1 at 7 T being a factor in achieving a significant SNR gain at 7 T, a greater factor that helped achieve such a gain is an increased field strength. The increase in B0 from 4 to 7 T should provide 116% gain in SNR according to the first term on the right side of Eq. (5). The interplay among the SNR gains contributed by the increased B0 and shortened T1 and the SNR losses caused by shortened T2* and degraded Q, which alone reduced 22% SNR according the second term on the right side of Eq. (5), leads to a net SNR gain of 56% at 7 T as compared with 4 T. If one assumes that the same Q value of the 31P surface coil could be achieved at both 4 and 7 T (i.e., Q(7 T)/Q(4 T) =1 in Eq. (5)), then the predicted net SNR gain at 7 T will increase from 56% to 99.5% according to Eqs. (4) and (5). In fact, it has been demonstrated that the RF coil Q usually could increase when B0 increases within a wide range of resonant frequency up to 200 MHz [22]. Therefore, it is plausible that the SNR of in vivo 31P MRS can further increase with a better than linear relation as a function of B0.

In conclusion, we have established a rigorous approach to quantitatively determine and compare the NMR detection sensitivity at different field strengths. The β power term as measured by the approach was consistent with the theoretically predicted β value. Eqs. (4) and (5) should be useful in estimating the field dependence of NMR detection sensitivity beyond 4 and 7 T, and they are also valid for other nuclei. The results from this study clearly indicate the advantages and benefits of in vivo 31P MRS at 7 T in terms of improvements in both detection sensitivity and spectral resolution. Such improvements should (a) make high-field in vivo 31P MRS capable of precisely determining HEP metabolites, other phosphate compounds actively involved in the phospholipid metabolism and chemical exchange kinetic rates noninvasively (e.g., the measurement of the ATP synthesis rate in the human occipital lobe [14]) and (b) improve the reliability and applicability of in vivo 31P MRS in studying HEP metabolism and biogenetics in the human brain, as well as (potentially) in other organs (e.g., heart and skeletal muscle), at both normal physiological and diseased states noninvasively.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Peter Andersen, Hao Lei, Nanyin Zhang and Kamil Ugurbil for their insightful discussion, support and technical assistance.

Footnotes

This work was partially supported by NIH Grants NS38070, NS41262, EB00329 and P41 RR08079; WM Keck Foundation; and the MIND Institute.

References

- 1.Shulman RG, Brown TR, Ugurbil K, Ogawa S, Cohen SM, den Hollander JA. Cellular applications of 31P and 13C nuclear magnetic resonance. Science. 1979;205:160–6. doi: 10.1126/science.36664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ackerman JJH, Grove TH, Wong GG, Gadian DG, Radda GK. Mapping of metabolites in whole animals by 31P NMR using surface coils. Nature. 1980;283:167–70. doi: 10.1038/283167a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lei H, Zhu XH, Zhang XL, Ugurbil K, Chen W. In vivo 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy of human brain at 7 T: an initial experience. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49:199–205. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiner MW. NMR spectroscopy for clinical medicine. Animal models and clinical examples Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1987;508:287–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb32911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ross BM, Moszczynska A, Blusztajn JK, Sherwin A, Lozano A, Kish SJ. Phospholipid biosynthetic enzymes in human brain. Lipids. 1997;32:351–8. doi: 10.1007/s11745-997-0044-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gadian DG, Williams SR, Bates TE, Kauppinen RA. NMR spectroscopy: current status and future possibilities. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien) 1993;57:1–8. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-9266-5_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Welch KM, Levine SR, Martin G, Ordidge R, Vande Linde AM, Helpern JA. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy in cerebral ischemia. Neurol Clin. 1992;10:1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hetherington HP, Pan JW, Spencer DD. 1H and 31P spectroscopy and bioenergetics in the lateralization of seizures in temporal lobe epilepsy. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2002;16:477–83. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown GG, Levine SR, Gorell JM, Pettegrew JW, Gdowski JW, Bueri JA, et al. In vivo 31P NMR profiles of Alzheimer’s disease and multiple subcortical infarct dementia. Neurology. 1989;39:1423–7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.39.11.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pettegrew JW, Minshew NJ. Molecular insights into schizophrenia. J Neural Transm Suppl. 1992;36:23–40. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-9211-5_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frosen S, Hoffman RA. Study of moderately rapid chemical exchange by means of nuclear magnetic double resonance. J Chem Phys. 1963;39:2892–901. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alger JR, Shulman RG. NMR studies of enzymatic rates in vitro and in vivo by magnetization transfer. Q Rev Biophys. 1984;17:83–124. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500005266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ugurbil K. Magnetization transfer measurements of creatine kinase and ATPase rates in intact hearts. Circulation. 1985;72:IV94–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lei H, Ugurbil K, Chen W. Measurement of unidirectional Pi to ATP flux in human visual cortex at 7 T by using in vivo 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:14409–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2332656100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barker PB, Hearshen DO, Boska MD. Single-voxel proton MRS of the human brain at 1.5T and 3.0T. Magn Reson Med. 2001;45:765–9. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonen O, Gruber S, Li BS, Mlynarik V, Moser E. Multivoxel 3D proton spectroscopy in the brain at 1.5 versus 3.0 T: signal-to-noise ratio and resolution comparison. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22:1727–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tkac I, Andersen P, Adriany G, Merkle H, Ugurbil K, Gruetter R. In vivo 1H NMR spectroscopy of the human brain at 7 T. Magn Reson Med. 2001;46:451–6. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boska MD, Hubesch B, Meyerhoff DJ, Twieg DB, Karczmar GS, Matson GB, et al. Comparison of 31P MRS and 1H MRI at 1.5 and 2. 0 T Magn Reson Med. 1990;13:228–38. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910130206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hardy CJ, Bottomley PA, Roemer PB, Redington RW. Rapid 31P spectroscopy on a 4-T whole-body system. Magn Reson Med. 1988;8:104–9. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910080113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hetherington HP, Spencer DD, Vaughan JT, Pan JW. Quantitative 31P spectroscopic imaging of human brain at 4 Tesla: assessment of gray and white matter differences of phosphocreatine and ATP. Magn Reson Med. 2001;45:46–52. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200101)45:1<46::aid-mrm1008>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ernst RR, Bodenhausen G, Wokaun A. Principles of nuclear magnetic resonance in one and two dimensions. New York: Oxford University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoult DI, Richards RE. The signal-to-noise ratio of nuclear magnetic resonance experiment. J Magn Reson. 1976;24:71–85. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silver MS, Joseph RI, Chen CN, Sank VJ, Hoult DI. Selective population inversion in NMR. Nature. 1984;310:681–3. doi: 10.1038/310681a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hendrich K, Hu X, Menon R, Merkle H, Camarata P, Heros R, et al. Spectroscopic imaging of circular voxels with a two-dimensional Fourier-series window technique. J Magn Reson. 1994;105:225–32. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1994.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Z, Wang DJ, Noyszewski EA, Bogdan AR, Haselgrove JC, Reddy R, et al. Sensitivity of in vivo MRS of the N-delta proton in proximal histidine of deoxymyoglobin. Magn Reson Med. 1992;27:362–7. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910270217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evelhoch JL, Ewy CS, Siegfried BA, Ackerman JJ, Rice DW, Briggs RW. 31P spin-lattice relaxation times and resonance linewidths of rat tissue in vivo: dependence upon the static magnetic field strength. Magn Reson Med. 1985;2:410–7. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910020409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mathur-De Vre R, Maerschalk C, Delporte C. Spin-lattice relaxation times and nuclear Overhauser enhancement effect for 31P metabolites in model solutions at two frequencies: implications for in vivo spectroscopy. Magn Reson Imaging. 1990;8:691–8. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(90)90003-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vaughan JT, Garwood M, Collins CM, Liu W, DelaBarre L, Adriany G, et al. 7T vs. 4T: RF power, homogeneity, and signal-to-noise comparison in head images. Magn Reson Med. 2001;46:24–30. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu XH, Merkle H, Kwag JH, Ugurbil K, Chen W. 17O relaxation time and NMR sensitivity of cerebral water and their field dependence. Magn Reson Med. 2001;45:543–9. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]