Abstract

Objective

The penalty point system was introduced in Italy in June 2003. The aim of this study was to evaluate the health effects of this legislation in the Lazio region.

Methods

Poisson models were used to compare emergency department visits, hospitalizations and death between the pre‐law and post‐law periods (July 2001–June 2003; July 2003–June 2004).

Results

The emergency department visit rate ratio (RR) of the two periods was 0.87 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.86 to 0.88); the corresponding hospital admission RR was 0.87 (95% CI 0.84 to 0.9). The death RR was 0.93 (95% CI 0.82 to 1.05).

Conclusion

After the legislation was introduced, there were fewer visits to the emergency department, hospitalizations and death from road traffic injuries. However, the effect was lower than expected, and it decreased over time.

Traffic accidents are the leading cause of death and disability among young people in Italy.1 The economic costs of traffic injuries are enormous. Although studies evaluating the effects of legislation aimed at reducing traffic injuries are scarce, especially in southern European countries, where adherence to the legislation tends to be poor,2,3,4 they did find a positive effect of the helmet law. Other studies have evaluated the effectiveness of speed cameras and found this intervention to reduce the number of causalities, the number of injured people and the number of deaths, although the amount of evidence was poor5; studies evaluating various restrictions on licenses for young drivers showed positive effects.6,7

On 30 June 2003, a new traffic law was enacted in Italy, which introduced the penalty point system. The penalty point system is intended to deter drivers from driving unsafely. Drivers begin with 20 points and lose points each time they commit a traffic violation. Serious offences, such as drunk driving, driving under the influence of substances, failing to stop and aid an injured person after a crash or exceeding the speed limit by >40 km/h are given the highest points. The new system, with the prospect of more severe penalties, was widely publicized by the media at the time of its implementation, and initially was enforced by increasing police control.

The aim of this study is to evaluate the health effects, as measured by deaths, hospital admissions and emergency department visits, of the new traffic law in the Lazio region.

Methods

Design

Before and after study.

Subjects

Subjects were all people who had a road traffic injury (RTI) and who visited one of 30 (of 56) emergency departments that participated in the study in Lazio, central Italy (5.3 million inhabitants, including the city of Rome). Twenty six emergency departments had to be excluded from the analysis because they were involved in another study on traffic and home injuries in the same period. On arrival at the emergency department, patients reported the circumstances/location of the injury (home, road, work, intentional violence, school, sport and other) to the attending nurse.

Sources of information

The Emergency Information System records, for each patient visit, demographic variables, medical condition at arrival and up to four diagnoses classified according to the clinical modification of the International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, which is the version currently used in Italy. The database reports the outcome of the admission: hospitalization, death or discharge.

The Mortality Registry records sociodemographic characteristics and the cause of death from death certificates, according to the International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision.

Data analysis

We selected all visits between July 2001 and July 2004 from the Emergency Information System, wherein road was reported as the location of the injury. We eliminated visits by the same person within 48 h of the initial emergency department visit. Details on the case definition have been published elsewhere.8

We compared the number of RTI emergency department visits before and after the application of the new traffic law legislation (July 2003). A Poisson model was used to compare visits from the two time periods, adjusting for age and sex. We used the same method to compare hospitalizations, extracting from the emergency department database all visits during which the outcome was “hospital admission”.

We compared the number of deaths by external cause RTI (E:810–819) from July 2003 to June 2004 with those from July 2001 to June 2003.

We calculated the p value for trend using the moving average approach. We estimated the number of deaths avoided after the new legislation by calculating the difference between observed deaths and expected deaths by semester, based on mortality trends since 1996.

Results

During the pre‐law period (1 July 2001–30 June 2003), there were 164 323 emergency department visits for RTI; during the post‐law period (1 July 2003–30 June 2004), there were 72 791 emergency department visits for RTI, a 12% reduction. Similar results were found for hospital admissions, which were 13.2% lower in the post‐law period. The mortality database showed 541 RTI deaths before the law, compared with 503 deaths afterwards, a 7% decrease.

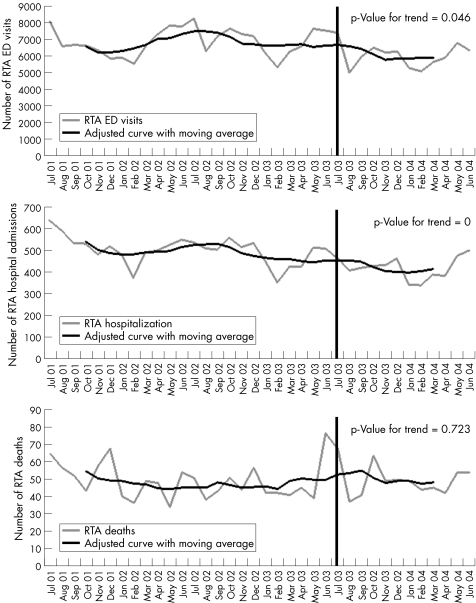

Figure 1 shows the number of RTI emergency department visits, hospital admissions and deaths by month in the study period. Emergency department visit and hospital admission trends seem to decrease, whereas the number of deaths is stable.

Figure 1 Number of road traffic accident (RTA) emergency department visits, number of RTA hospital admissions and number of RTA deaths by month. The vertical line represents the introduction of the new road code (30 June 2003). Italy, Lazio 2001–4.

Table 1 lists the results of the Poisson models. The emergency department visit rate ratio (RR) of the before and after periods is 0.88 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.87 to 0.89). RRs increase with age, with the strongest reduction seen among infants (<4 years of age). The effect was significantly stronger outside the metropolitan area of Rome than in the city itself. The RRs were similar for hospitalizations. The mortality RR of the before and after periods is 0.96 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.07).

Table 1 Emergency department visit, hospital admissions and mortality rate ratios before and after the introduction of the new road code (30 June 2003, Italy, Lazio 2001–4).

| Before point system | After point system | RR post v pre | 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/Jul/2001– 30/Jun/2003 | Person‐years | 1/Jul/2003– 30/Jun/2004 | Person‐years | |||

| RTA emergency department visits | ||||||

| Overall | 164 323 | 10 291 610 | 72 787 | 5 145 805 | 0.88 | 0.87 to 0.89 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Males | 96 202 | 4 932 056 | 42 972 | 2 466 028 | 0.89 | 0.88 to 0.90 |

| Females | 68 121 | 5 359 554 | 29 815 | 2 679 777 | 0.87 | 0.86 to 0.89 |

| Age groups (years) | ||||||

| 0–4 | 1939 | 460 280 | 645 | 230 140 | 0.66 | 0.61 to 0.73 |

| 5–14 | 9601 | 967 956 | 3315 | 483 978 | 0.69 | 0.66 to 0.72 |

| 15–29 | 63 815 | 1 812 524 | 27 959 | 906 262 | 0.87 | 0.86 to 0.89 |

| 30–64 | 75 219 | 5 153 634 | 35 077 | 2 576 817 | 0.93 | 0.92 to 0.94 |

| >65 | 13 749 | 1 897 216 | 5791 | 948 608 | 0.84 | 0.82 to 0.87 |

| Place of residence | ||||||

| City of Rome | 76 735 | 5 185 350 | 35 994 | 2 592 675 | 0.94 | 0.93 to 0.95 |

| Outside Rome | 87 588 | 5 106 260 | 36 793 | 2 553 130 | 0.84 | 0.83 to 0.85 |

| RTA hospital admissions | ||||||

| Overall | 11 960 | 10 291 610 | 5035 | 5 145 805 | 0.84 | 0.81 to 0.87 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Males | 7681 | 4 932 056 | 3371 | 2 466 028 | 0.88 | 0.84 to 0.91 |

| Females | 4279 | 5 359 554 | 1664 | 2 679 777 | 0.77 | 0.73 to 0.82 |

| Age groups (years) | ||||||

| 0–4 | 150 | 460 280 | 51 | 230 140 | 0.68 | 0.49 to 0.93 |

| 5–14 | 711 | 967 956 | 283 | 483 978 | 0.79 | 0.69 to 0.91 |

| 15–29 | 4353 | 1 812 524 | 1747 | 906 262 | 0.80 | 0.76 to 0.85 |

| 30–64 | 4671 | 5 153 634 | 2118 | 2 576 817 | 0.91 | 0.86 to 0.95 |

| >65 | 2075 | 1 897 216 | 836 | 948 608 | 0.81 | 0.74 to 0.87 |

| Place of residence | ||||||

| City of Rome | 4577 | 5 185 350 | 2113 | 2 592 675 | 0.92 | 0.88 to 0.97 |

| Outside Rome | 7383 | 5 106 260 | 2922 | 2 553 130 | 0.79 | 0.76 to 0.83 |

| RTA deaths | ||||||

| Overall | 1046 | 10 291 610 | 503 | 5 145 805 | 0.96 | 0.86 to 1.07 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Males | 862 | 4 932 056 | 398 | 2 466 028 | 0.92 | 0.82 to 1.04 |

| Females | 184 | 5 359 554 | 105 | 2 679 777 | 1.14 | 0.89 to 1.45 |

| Age groups (years) | ||||||

| 0–4 | 5 | 460 280 | 2 | 230 140 | 0.80 | 0.15 to 4.12 |

| 5–14 | 8 | 967 956 | 8 | 483 978 | 2.00 | 0.75 to 5.33 |

| 15–29 | 321 | 1 812 524 | 147 | 906 262 | 0.91 | 0.75 to 1.11 |

| 30–64 | 429 | 5 153 634 | 203 | 2 576 817 | 0.95 | 0.80 to 1.12 |

| >65 | 283 | 1 897 216 | 143 | 948 608 | 1.01 | 0.82 to 1.24 |

| Place of residence | ||||||

| City of Rome | 477 | 5 185 350 | 210 | 2 592 675 | 0.88 | 0.74 to 1.03 |

| Outside Rome | 569 | 5 106 260 | 293 | 2 553 130 | 1.03 | 0.89 to 1.19 |

RTA, road traffic accident.

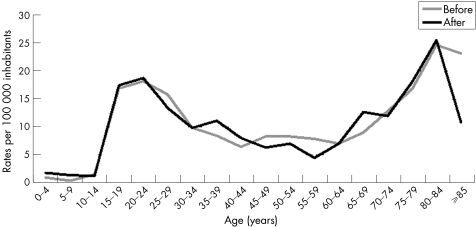

Figure 2 shows mortalities of the two periods in the different age groups; there is no evident decrease in any group.

Figure 2 Road traffic accident mortalities by age before and after the introduction of the new road code (30 June 2003). Italy, Lazio 2001–4.

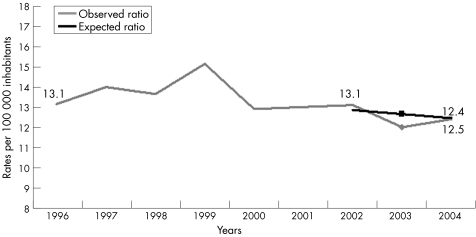

Figure 3 displays the number of deaths avoided since the enactment of the legislation. In all, 32 deaths were prevented in 2003, 5 in the first semester and 27 in the second. The expected/observed ratio for 2004 is 1.

Figure 3 Road traffic accident mortalities observed and expected (by a Poisson regression). Italy, Lazio 1996–4.

Discussion

After the new penalty system was introduced in 2003, there were 12% fewer RTI emergency department visits than in the year before. Hospitalizations decreased by 16%, and there were 4% fewer deaths. Results of the Poisson model show that the reductions in emergency department visits and hospital admissions were significant, but the decrease in the number of deaths was not. This study shows that the number of negative health consequences of RTI decreased slightly after the introduction of the new legislation. The decrease in deaths observed is consistent with a long‐term reduction of RTI deaths and injuries that has already been seen over recent decades, limiting the strengths of our results to the first few months.9,10

This is a before and after study, which typically does not allow adjusting for confounders. We considered the effects of only sex and age in the analysis. We analysed data at 2 years before and at 1 year after the law's enactment, and tried to take into account any seasonal effects.

Circumstances of injuries were not recorded in the emergency department or hospital admissions databases, which prevented any analysis of how circumstances may have changed as a result of the point system. Another limit was the inability of using exposure data. We checked for consistent variations in the passenger volume transport. The Italian Environmental Agency reports10 information on passenger volume transport and shows no strong variations from 2000 until 2004 (latest available information).

One strength of the study is that we analysed final outcomes (injuries and death) to evaluate the effectiveness of the new legislation reported in healthcare databases rather than police reports.11 Healthcare data suggested a weaker effect than that suggested by the official road traffic accident databases.9

It is difficult to compare the new point system in Italy with similar laws in other countries. In other countries, the introduction of compulsory helmet and seat belt laws have led to reduction in death ranging from 25% to 70%3,12,13,14,15,16; however, the effects of the new point system in Italy were not as noticeable, probably because it was preceded by similar legislation, which was effective in reducing the severity of injuries, like the compulsory helmet law in January 1986 for adults and in March 2000 for all two‐wheel users.2 One study, conducted in Ireland, on the effectiveness of penalty point legislation,17 analyzed its effect on admissions to a level 1 trauma center, and observed a 37% reduction in admissions. The effectiveness of a law depends on the police enforcement strategy18; our study shows that the point system was particularly effective when enforcement was particularly strong, as in the first months of its application. Another Italian study suggested that adherence to the Italian helmet law has been insufficient in part because of a lack of law enforcement.4

An evaluation conducted by the National Institute of Statistics using police crash reports9 showed 19.5% and 11.5% reductions in the number of deaths and injuries, respectively, in the second semester of 2003 compared with the same period of the preceding year. Despite the positive effect in the first 6 months of applying the law, trends in the first semester of 2004 showed less of an effect on the number of deaths and injuries compared with those in 2003, and no effect in the second semester of 2004. The official statistics are consistent with our results.

Conclusions

This study shows a positive effect of the new point system. The effect on deaths was found to be not significant. To reduce the number of RTI deaths, a concerted effort of consistent law enforcement, adequate police control and health promotion programs has to be made. In addition, improvements of the health databases are needed to evaluate the efficacy of future interventions.

Key points

After the new penalty system was introduced in 2003, there were fewer emergency department visits, hospitalizations and deaths from road traffic accidents than in the year before.

The decrease in deaths observed is consistent with the steady decline in road traffic injury (RTI) deaths and injuries over recent decades, limiting the strengths of our results to the first few months.

Our study shows that the point system was particularly effective when enforcement was particularly strong, as in the first months of its application.

A concerted effort has to be made to reduce the number of RTI deaths, which should include consistent law enforcement, adequate police control and health promotion programmes.

Improvements in health databases are needed to evaluate the efficacy of future interventions.

Acknowledgement

We thank the staff of the Hospital Information System of the Lazio Region, particularly Paolo Papini, Valeria Tancioni and Riccardo Salvatori; the staff of the Emergency Information System, particularly Assunta de Luca; and Alessandra Sperati of the Mortality Registry. We also thank Maurizio Di Giorgio for his invaluable suggestions, and Margaret Becker, who edited the manuscript.

Abbreviations

RTI - road traffic injury

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.ISTAT Cause di Morte anno 2001. Annuario no 17. Rome: ISTAT, 2005

- 2.Servadei F, Begliomini C, Gardini E.et al Effect of Italy's motorcycle helmet law on traumatic brain injuries. Inj Prev 20039257–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrando J, Plasencia A, Oros M.et al Impact of a helmet law on two wheel motor vehicle crash mortality in a southern European urban area. Inj Prev 20006184–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.LaTorre G, Bertazzoni G, Zotta D.et al Epidemiology of accidents among users of two‐wheeled motor vehicles. A surveillance study in two Italian cities. Eur J Public Health 20021299–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pilkington P, Kinra S. Effectiveness of speed cameras in preventing road traffic collisions and related casualties: systematic review. BMJ 2005330331–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shope J T, Molnar L J. Graduated driver licensing in the United States: evaluation results from the early programs. J Safety Res 20033463–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen L H, Braver E R, Baker S P.et al Potential benefits of restrictions on the transport of teenage passengers by 16 and 17 year old drivers. Inj Prev 20017129–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giorgi Rossi P, Farchi S, Chini F.et al Road traffic injuries in Lazio, Italy: a descriptive analysis from an emergency department‐based surveillance system. Ann Emerg Med 200546152–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ISTAT Statistiche degli incidenti stradali. Anni 2003–2004. Informazioni. Rome: ISTAT, 2005

- 10.APAT Annuario dei Dati ambientali. Rome: APAT, 2006

- 11.Racioppi F, Eriksson L, Tingvall C.et alPreventing road traffic injury: a public health perspective. Geneva: WHO, 2004

- 12.Keng S H. Helmet use and motorcycle fatalities in Taiwan. Accid Anal Prev 200537349–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reinfurt D W, Campbell B J, Stewart J R.et al Evaluating the North Carolina safety belt wearing law. Accid Anal Prev 199022197–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chorba T L, Reinfurt D, Hulka B S. Efficacy of mandatory seat‐belt use legislation. The North Carolina experience from 1983 through 1987. JAMA 19882603593–3597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marburger E A, Friedel B. Seat belt legislation and seat belt effectiveness in the Federal Republic of Germany. J Trauma 198727703–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koushki P A, Bustan M A, Kartam N. Impact of safety belt use on road accident injury and injury type in Kuwait. Accid Anal Prev 200335237–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lenehan B, Street J, Barry K.et al Immediate impact of ‘penalty points legislation' on acute hospital trauma services. Injury 200536912–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Redelmeier D A, Tibshirani R J, Evans L. Traffic‐law enforcement and risk of death from motor‐vehicle crashes: case‐crossover study. Lancet 20033612177–2182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]