Abstract

Background

Nicotine deprivation symptoms, including fatigue and attentional deficits, predict relapse following smoking cessation. Modafinil (Provigil), a wakefulness medication shown to have efficacy for the treatment of cocaine addiction, was tested as a novel therapy for nicotine dependence in a double-blind placebo-controlled trial.

Methods

157 treatment-seeking smokers received brief smoking cessation counseling and were randomized to: 1) 8 weeks of modafinil (200mg/day), or 2) 8 weeks of placebo. The primary outcome was biochemically verified 7-day point prevalence abstinence at the end of treatment. Secondary outcomes included cigarette smoking rate and post-quit nicotine deprivation symptoms (e.g., negative affect, withdrawal).

Results

In this interim study analysis, end of treatment (EOT) quit rates did not differ between treatment arms (42% for placebo vs. 34% for modafinil; OR = 0.67 [0.34 – 1.31], p = .24). Further, from the target quit date to EOT, the daily smoking rate was 44% higher among non-abstainers in the modafinil arm, compared to non-abstainers in the placebo arm (IRR = 1.44, CI95 = 1.09–1.89, p < .01). Modafinil-treated participants also reported greater increases in negative affect and withdrawal symptoms, vs. participants randomized to placebo (ps < .05).

Conclusions

These data do not support the use of modafinil for the treatment of nicotine dependence and, as a consequence, this trial was discontinued. Cigarette smoking should be considered when modafinil is prescribed, particularly among those with psychiatric conditions that have high comorbidity with nicotine dependence.

Keywords: nicotine dependence, smoking cessation, addiction, modafinil

1.0 Introduction

In the past several decades, there have been great advances in reducing the prevalence of smoking (Centers for Disease Control [CDC], 2004). One factor contributing to this success has been the development of pharmacotherapies for nicotine dependence, including nicotine replacement therapies (NRTs), bupropion, and varenicline. Yet, only 20–30% of smokers treated with these medications achieve long-term abstinence (Cahill et al., 2007; Hughes et al., 2007; Silagy et al., 2004). Consequently, there is a critical need to develop new pharmacotherapies for nicotine dependence.

Modafinil (Provigil) is approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (US FDA) as a wakefulness-promoting agent for excessive sleepiness associated with narcolepsy, obstructive sleep apnea, and shift work sleep disorder (Ballon and Feifel, 2006). There were two compelling reasons for testing modafinil as a potential therapy for nicotine dependence. First, modafinil produces clinical effects that may alleviate nicotine withdrawal symptoms which, in turn, predict relapse to smoking (Lerman et al., 2002). In healthy volunteers, modafinil enhances energy and alertness and reduces fatigue and daytime sleepiness (Baranski et al., 2004; Walsh et al., 2004), improves attention and task performance and reduces impulsivity (Turner et al., 2003), and reduces food intake (Makris et al., 2004). Among depressed patients, modafinil, improves mood, alone (Mitchell, 1995), and in combination with anti-depressants (Menza et al., 2000). The cognitive enhancing effects of modafinil have been observed in several clinical psychiatric populations, including individuals with schizophrenia, major depression, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; Minzenberg and Carter, 2007). Second, modafinil has been shown to have efficacy for the treatment of cocaine dependence in a placebo-controlled trial with cocaine addicts (Dackis et al., 2005). Although the effect of modafinil on tobacco use rates were not assessed in the Dackis et al. (2005) trial, the neurobiology underlying the rewarding effects of cocaine and nicotine may similarly involve dopamine and glutamate concentration (Nestler, 2005), which are affected by modafinil. Further, upwards of 75% of cocaine-dependent individuals are nicotine dependent (Budney et al., 1993; Lai et al., 2000).

Thus, we conducted an 8-week double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial to test the efficacy of modafinil for treating nicotine dependence. We also assessed the effects of modafinil on nicotine abstinence symptoms that promote relapse (e.g., withdrawal, negative affect) and evaluated treatment adherence and side effects and adverse events. This report represents the results of a planned interim analysis with 50% of the target sample. Based on the results which follow, this trial was discontinued.

2.0 Methods

2.1 Participants

Subjects were recruited via advertisements for a free smoking cessation program at the University of Pennsylvania (PENN) and Thomas Jefferson University (TJU) Hospital and enrolled between November 2005 and June 2007. Subjects were over age 18 and smoked at least 10 cigarettes/day for the past year. Exclusion criteria were: 1) current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-IV-Revised (DSM-IV-R) Axis I disorder based on the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI); 2) lifetime history of psychotic, bipolar, or eating disorder; 3) excessive alcohol use (>25 standard units of alcohol/week) or current use of opiates, cocaine, or stimulants; 4) current use of NRT or bupropion; 5) current use of an anti-depressant, an antipsychotic, an anxiolytic, or over-the-counter stimulants and anorectics; 6) a lifetime history of irregular heartbeat, myocardial infarction, stroke, or uncontrolled hypertension; 7) any disorder that interferes with drug absorption or metabolism; 8) women who were pregnant or lactating; 9) a diagnosis of a sleep disorder; and 10) a history of serious brain injury or seizure disorder.

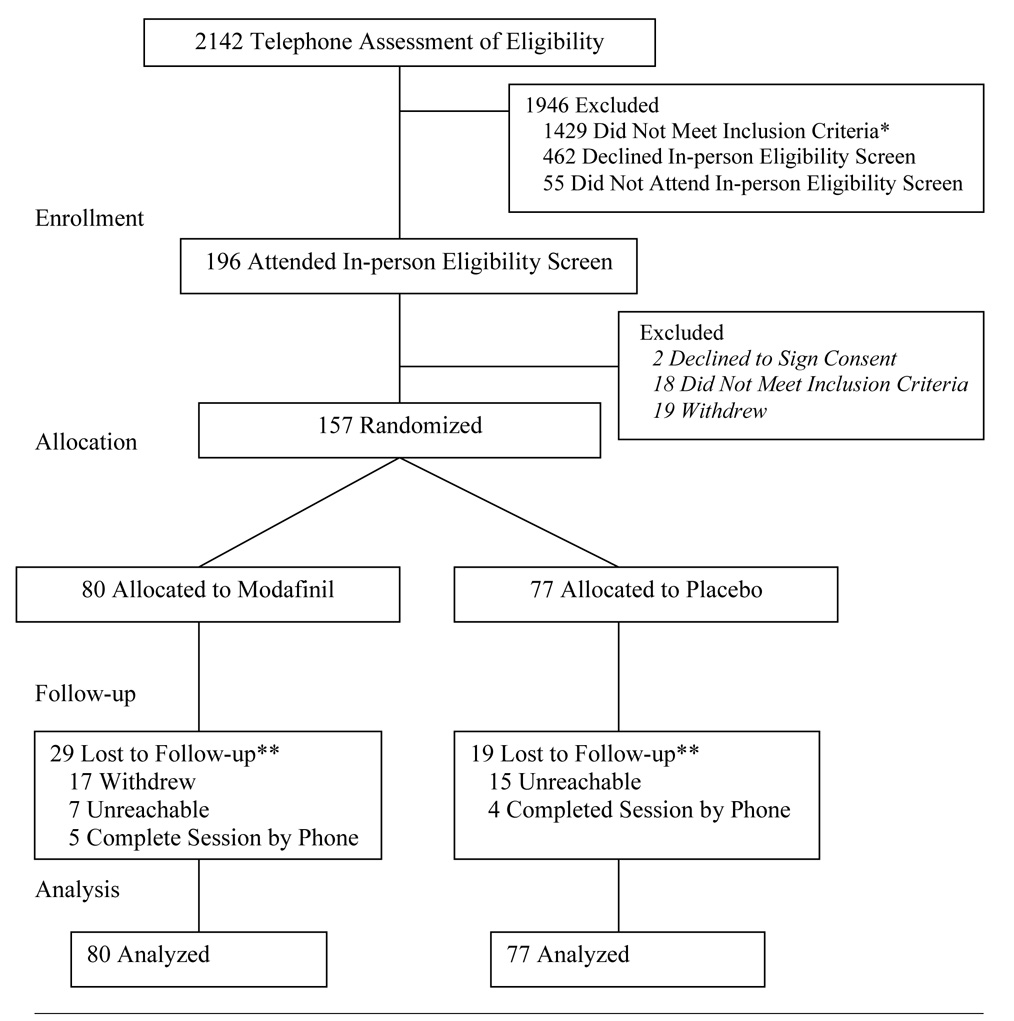

Study accrual and retention is shown in Figure 1. Over 2100 individuals were evaluated for eligibility by telephone; 1429 were ineligible, 462 declined to undergo in-person eligibility screening, and 55 individuals who were eligible during the telephone assessment, did not attend in-person screening. One-hundred ninety-six individuals attended an in-person medical screening; 18 were ineligible, 2 individuals declined to sign consent, and 19 individuals withdrew. The remaining 157 eligible individuals were randomized to study arms and were included in the intent-to-treat analysis. Randomization was stratified across the treatment sites.

Figure 1. Participant Flow.

Note. * A list of the reasons for participant ineligibility can be provided by the authors upon request; ** indicates included in intent-to-treat analysis.

2.2 Study Procedures

All procedures for this double-blind trial were approved by the PENN and TJU Institutional Review Boards. Procedures were standardized across treatment sites. All eligibility screening and medication distribution was performed at PENN, a study orientation was conducted by the same investigator at both sites, counselors were trained and supervised to ensure cross-site compliance with procedures, and data collection was standardized across sites.

Initial telephone eligibility screening was performed, followed by an in-person medical exam. The MINI screened for DSM-IV-R psychiatric disorders. Eligible participants provided written informed consent and were randomized to placebo or modafinil using a computer-generated random numbers table. At baseline, participants completed self-report measures of demographics, smoking history (e.g. Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence [FTND]; Heatherton et al., 1991), alcohol consumption, and psychological variables (e.g., the Center for Epidemiology-Depression Scale [CES-D]; Radloff, 1977; the Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Current Symptom Scale; Barkley and Murphy, 1998).

Following a pre-quit counseling session at week 0 (baseline), study medication was initiated and taken for 8 weeks. A target quit date was set for Week 1. Assessments occurred at 1, 4, and 8 weeks following baseline. Withdrawal symptoms, craving, mood, depression symptoms, and side effects were evaluated at all time-points. Blood pressure was assessed at week 0 (baseline) and week 4. Smoking rate was assessed using a time-line follow-back measure (TLFB; Brown et al., 1998) and participants provided a carbon monoxide (CO) sample to verify self-reported cessation. The week 8 survey completion rate was 75%. Daily pill use was tracked.

2.3 Treatment

Following the pre-quit baseline visit at week 0, participants began their medication. Participants randomized to receive modafinil took two 100mg capsules each day first thing in the morning. Participants randomized to placebo took two matched pills containing no active medication each day. Pills were distributed by the PENN Research Pharmacy, which maintained the study blind. Significant side effects were reviewed by the study physician. Serious adverse events were reported and medication was discontinued if needed. Participants also received standardized behavioral smoking cessation counseling including one small group (pre-quit) session at week 0 plus 2 individual booster sessions (10–15 minutes each) at weeks 1 and 4. Counseling focused on preparing for cessation and managing temptations and triggers to smoking to avoid relapse. Participants were instructed to continue medication use during lapses. Medication adherence was emphasized during all contacts.

2.4 Outcomes

2.4.1. Abstinence and Smoking Rate

As recommended (Hughes et al., 2003), we report 7-day point prevalence abstinence at week 8 as the primary outcome. This measure was verified with CO (cutoff of ≤ 10ppm). Based on self-report, verified by CO, 59 participants were abstinent. As per convention, the remaining 98 participants were considered smokers since their CO was > 10ppm (n = 51) or they did not provide CO data (n = 47; SRNT, 2001). Self-reported daily smoking rate, assessed with the TLFB, was examined as a secondary outcome. Typically, smoking cessation clinical trials assess cessation rates 6- or 12-months post-target quit day. However, since this was the first trial of modafinil for nicotine dependence, we considered assessment of immediate treatment effects to be critical. If the present trial indicated an effect at the end of treatment (EOT), long-term effects would be evaluated in larger clinical trials.

2.4.2. Intermediate Outcomes

Changes in abstinence symptoms and side effects were based on comparing self-report measures administered at baseline to week 4 measures; changes in blood pressure across treatment arm were also assessed by comparing measures from week 0 to week 4. A checklist of withdrawal symptoms was administered to assess withdrawal symptoms related to quitting smoking (Hughes et al., 1984). This checklist consists of 18 items (e.g., irritability, difficulty concentrating) rated in terms of intensity from 0 = not present to 3 = severe. Two Likert-style items from this scale, shown to predict smoking relapse (Killen and Fortmann, 1997) represented smoking urges. The CES-D, a 20-item Likert-style scale, assessed depressive symptoms (Radloff, 1977). The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS), a 20-item Likert-format self-report measure, was used to assess positive affect (e.g., enthusiastic, strong) and negative affect (e.g., distressed, upset; Watson et al., 1988). Side effects (e.g., dry mouth, dizziness) were assessed using a checklist with items rated as 0 = none to 3 = severe. Self-reported serious adverse events that required medical consultation were also tracked.

2.4.3. Treatment Adherence

A TLFB measure (Brown et al., 1998) assessed daily pill use from week 0–8. Total pill count was computed by summing the daily values. Percent compliant was computed by dividing total pill count by 112 (total number of pills prescribed).

2.5 Statistical Analysis

We calculated power for testing a difference in cessation rates at week 8 using the Power and Sample Size program (NCSS, Kaysville, Utah). We assumed a 2-sided test with alpha = 5%. With a sample of 300, we had 80% power to detect a 15% difference in quit rates between groups, assuming a 15% rate in the placebo group. The present results were based on a planned interim analysis when at least 50% of the projected sample was accrued.

All participants randomized were considered in the analysis regardless of adherence or follow-up status. SAS was used for statistical analyses. Baseline data were characterized and compared between treatment arms, treatment sites, and study completers and non-completers using analysis of variance (ANOVA) or chi-square. Random effects logistic regression was used to test effects of treatment arm on the primary outcome (7-day point prevalence), controlling for study site. We modeled daily smoking and self-reported abstinence rates with a longitudinal zero-inflated negative binomial model, adjusted for multiple observations using the robust covariance estimate. The moderating effects of baseline alcohol use and ADHD symptoms were also explored using separate regression analyses. Given the proposed mechanism of modafinil, this medication may be particularly effective for smokers with higher rates of ADHD symptoms; further, given data from cocaine dependence trials, modafinil may be more effective for those with lower rates of alcohol use (Haney and Spealman, in press). Treatment effects on abstinence symptoms, side effects, and pill count were tested using ANOVA. Analyses involving changes in average abstinence symptoms and side effects over time considered pre-treatment measures to assess relative change over time across treatment arms. The frequency of side effects rated by study participants as severe and all other self-reported serious adverse events are also described. Lastly, change in blood pressure from baseline to week 4 across treatment arms was tested using two-sample t-tests and difference scores.

3.0 Results

3.1 Descriptive Data

The average age of subjects was 46.5 years (SD = 9.7), 55% of subjects were female, 7% of the sample had grade school or just some high school, 20% of the sample had a high school diploma, 41% had some college education, and 31% had a college degree, 41% were of European ancestry, 52% were African American, and 6% reported other ancestry (one participant refused to provide race/ethnicity data). The average number of cigarettes smoked per day was 17.2 (SD = 7.2), the average FTND score was 5.1 (SD = 1.8), and the average baseline CO was 22.8ppm (SD = 11.7).

Seventy-seven participants were randomized to placebo and 80 participants were randomized to modafinil. There were no significant differences in participant baseline characteristics by treatment arm assignment (Table 1). There were no significant differences between week 8 survey completers and non-completers with respect to baseline demographic or smoking-related variables. Retention rates for the 8-week interview were no different across placebo and modafinil treatment arms (81% vs. 70%; χ2[1] = 2.34, p >.05). There were no significant differences across treatment sites in terms of demographic or smoking-related variables. However, there was a significant difference in abstinence rates between study sites (χ2[1] = 9.37, p < .05); thus, study site was included as a control variable in all models (Table 2).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics by Treatment Arm Assignment

| Characteristics | Placebo (n = 77) |

Modafinil (n = 80) |

Overall (n = 157) |

χ2(1df) or F (1, 377 df) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (% Female) | 54.5 | 55.0 | 54.8 | 0.003 | 1.0 |

| Age (Mean) | 45.4 | 47.5 | 46.5 | 1.91 | 0.2 |

| Education (% High School plus) | 69.7 | 75.0 | 72.4 | 0.54 | 0.5 |

| Race (% European Ancestry) | 37.7 | 45.0 | 41.4 | 0.87 | 0.4 |

| FTND (Mean) | 5.3 | 4.9 | 5.1 | 1.78 | 0.2 |

| Cigarettes per Day (Mean) | 17.1 | 17.3 | 17.2 | 0.02 | 0.9 |

| CO (ppm) | 20.9 | 23.4 | 22.2 | 1.76 | 0.2 |

| BMI (Mean) | 30.0 | 29.6 | 29.8 | 0.17 | .70 |

| Age Started Smoking (Mean) | 16.6 | 17.0 | 16.8 | 0.35 | .56 |

Note. FTND = Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence.

Table 2.

Logistic Regression Analysis of Point Prevalence Abstinence

| Predictor | OR | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment Site | 0.29 | 0.11 – 0.75 | .01 |

| Treatment Arm (Jefferson) | 0.57 | 0.20 – 1.60 | 0.29 |

| Treatment Arm (UPENN) | 0.76 | 0.31 – 1.84 | 0.54 |

Note. Treatment Site Coded 0 = Jefferson, 1 = UPENN; Treatment Arm Coded 0 = Placebo, 1 = Modafinil.

3.2 Effect of Treatment Arm on Abstinence and Smoking Rate

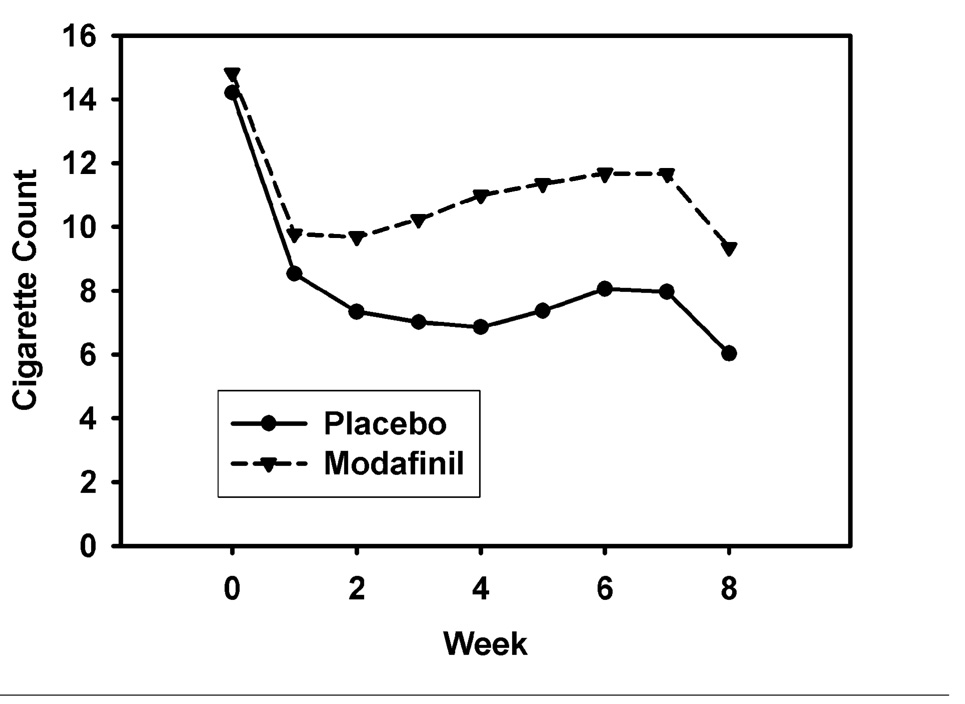

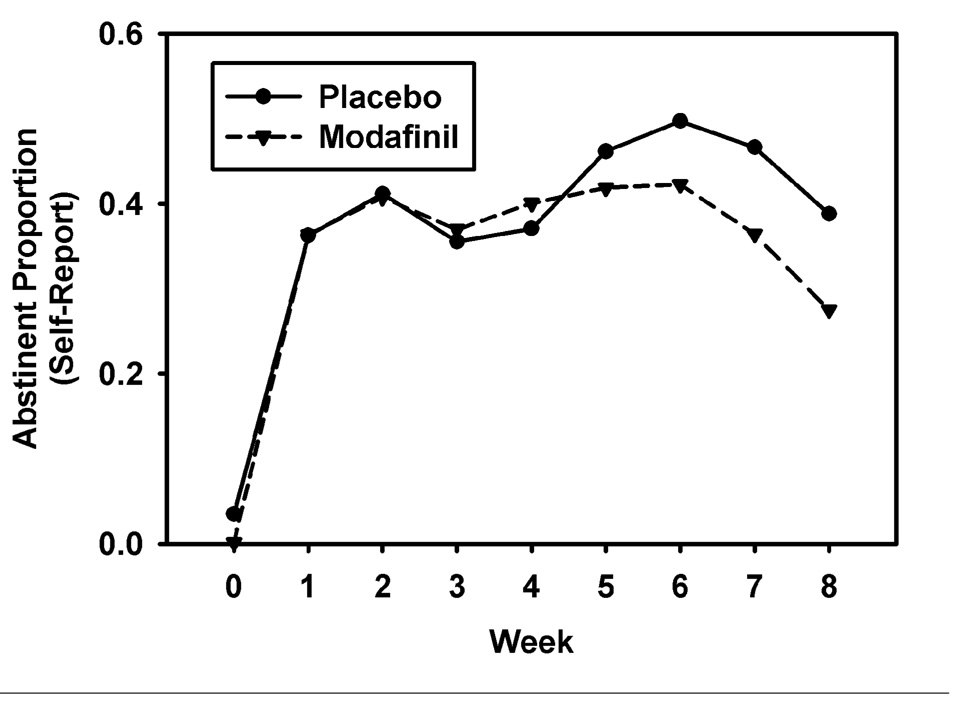

Controlling for treatment site, quit rates did not differ by treatment arm (placebo = 44.2%; modafinil = 34.0%; OR = 0.67 [0.34 – 1.31], p = .24). As shown in Table 2, assessment of treatment arm effect for each site individually was not statistically significant. The longitudinal zero-inflated negative binomial model of smoking rate treats the smoking rate as a mixture of daily cigarette counts for those not abstinent (these counts may include some zeros for those smoking irregularly), and additional zeros due to abstinence. The daily count for those not abstaining is modeled as a negative binomial and daily membership in the abstinent group is modeled using logistic regression. The model, adjusted for study week and treatment site, was significant overall (χ2[22] = 95.67, p < 0.0001). The treatment arm effect was statistically uniform over weeks 1 through 8 for abstinent rates, but significant for the negative-binomial (cigarette count) portion. The results of this model indicated that from target quit date to end-of-treatment (EOT) the daily smoking rate was 44% higher among non-abstainers in the modafinil arm, compared to non-abstainers in the placebo arm (IRR = 1.44, CI95 = 1.09–1.89, p < .01). The count model is reflected in Figure 2, separately for treatment arm. Across both treatment sites, non-abstainers in the modafinil arm reported higher average weekly smoking rates (cigarettes per day) at week 3 (IRR = 1.46, χ2(1) = 7.97, p < 0.005), week 4 (IRR = 1.60, χ2(1) = 8.17, p < 0.004), week 5 (IRR = 1.54, χ2(1) = 6.46, p < 0.01), week 6 (IRR = 1.45, χ2(1) = 4.67, p < 0.03), and week 7 (IRR = 1.46, χ2(1) = 4.94, p < 0.03), compared to non-abstainers in the placebo arm. There were no significant differences between treatment arms in terms of weekly abstinence rates (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Self-reported Smoking Rates for Modafinil and Placebo Arms, Week 0–8.

Note. Week 0 is pre-treatment. Treatment arm comparisons for smoking rate at weeks 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 (pooled across sites) are significant (ps < .05); smoking rate excludes abstainers; smoking rate calculated using average cigarettes per day for non-abstainers as unit of measure. Treatment effects are statistically homogenous over the treatment period from week 1 to week 8.

Figure 3. Proportion of Sample Abstinent by Self-Report for Modafinil and Placebo Arms, Week 0 to 8.

Note. Week 0 is pre-treatment. Treatment effects are statistically homogenous over the treatment period from week 1 to week 8.

Lastly, we examined baseline alcohol use (number of daily liquor, beer, or wine drinks) and ADHD symptoms as possible moderators of treatment arm effect and examined the effect of modafinil using an alternative cut-off for abstinence. Logistic regressions with interaction terms for alcohol use and ADHD symptoms revealed no significant interaction effects (p’s > .05). In addition, there was no significant treatment arm effect if we used 6ppm as the cut-off for abstinence (placebo arm quit rate = 26% and modafinil arm = 23%; OR = 0.83 [0.40 – 1.72], p = .61) as opposed to 10ppm.

3.3 Effect of Treatment Assignment on Intermediate Treatment Measures

Complete data on intermediate measures were ascertained from 117 participants (75%). Participants in the modafinil arm reported significant increases in depressive symptoms (F[1,115] = 5.66, p = .02), negative mood (F[1,115] = 4.78, p = .03), and withdrawal symptoms (F[1,115] = 6.88, p = .01) from baseline to week 4 (see Table 3). There were no significant treatment arm differences for positive mood, urge to smoke, or the summary score for the side-effects checklist. We also assessed possible differences in common modafinil side effects across treatment arms from baseline to week 4 (i.e., headache, dry mouth, nausea, nervousness, diarrhea, sleep problems). While there were no treatment arm differences over time in severity of headaches, dry mouth, and diarrhea, participants randomized to modafinil did experience a significant increase in the severity of nausea (F[1,115] = 6.05, p = .02) and nervousness (F[1,115] = 5.04, p = .03) over time, compared to participants randomized to placebo. The frequency of side effects rated as severe on the checklist is shown in Table 4, and there were 9 serious adverse events self-reported by different participants that required hospitalization (i.e., shortness of breath, two falls, chest and left arm pain and gastro-intestinal problems, racing heart, skin cancer, dental pain, chest and neck pain, and left arm tingling and chest and head pressure). There was no difference in the rate of serious adverse events between treatment arm (Placebo = 4 and Modafinil = 5; χ2[1] = 0.08, p = .78). Lastly, there was no treatment arm effect on change in systolic (t[107] = 0.72, p > .05) or diastolic (t[107] = 1.07, p > .05) blood pressure from baseline to week 4.

Table 3.

Effect of Treatment Arm Assignment on Intermediate Outcomes

| Characteristic | Placebo | Modafinil | F (1, 115 df) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Week 4 | Baseline | Week 4 | |||

| Depression Symptoms | 10.61 | 8.08 | 7.59 | 8.30 | 5.66 | .02 |

| Positive Mood | 32.71 | 29.92 | 33.18 | 32.09 | 1.43 | .23 |

| Negative Mood | 13.83 | 13.34 | 13.32 | 14.80 | 4.78 | .03 |

| Withdrawal Symptoms | 10.76 | 8.33 | 8.13 | 9.81 | 6.88 | .01 |

| Craving | 3.34 | 3.30 | 3.96 | 3.68 | 0.57 | .45 |

Table 4.

Frequency of Severe Side Effects across Treatment Arm

| Side Effect | Placebo (%) | Modafinil (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Headache | 2.6 | 1.3 |

| Nausea | 0 | 1.3 |

| Constipation | 1.3 | 2.5 |

| Fatigue | 3.9 | 0 |

| Dry Mouth | 1.3 | 3.8 |

| Indigestion | 1.3 | 2.5 |

| Flatulence | 3.9 | 3.8 |

| Nervousness | 0 | 1.3 |

| Insomnia | 3.9 | 1.3 |

| Eye Pain | 1.3 | 0 |

| Taste Problem | 0 | 1.3 |

| Chest Pain | 1.3 | 0 |

| Back Pain | 3.9 | 2.5 |

| Rhinitis | 1.3 | 0 |

| Sadness | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| Sore Throat | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| Decreased Appetite | 0 | 2.5 |

| Anxiety | 0 | 1.3 |

| Drowsiness | 2.6 | 0 |

| Numbness | 2.6 | 0 |

| Difficulty Breathing | 2.6 | 1.3 |

| Closing of Throat | 0 | 1.3 |

Total pill count data were ascertained from 103 participants (66%). On average, participants randomized to placebo used 93% of prescribed medication, compared to 90% for participants randomized to modafinil, which was not significantly different (F[1,101] = 1.24, p = .27). Adherence to medication was not related to week 8 quit rates for the entire sample (F[1,101] = 0.16, p >.05), among participants randomized to placebo (F[1,52] = 0.07, p>.05), or among participants randomized to modafinil (F[1,47] = 0.07, p>.05).

4.0 Discussion

These data do not support the efficacy of modafinil for treating nicotine dependence and our clinical trial was discontinued. Indeed, among non-abstainers, modafinil may have inhibited any reduction in smoking rate over time, compared to placebo, and increased withdrawal and negative mood symptoms during the treatment phase. Since modafinil did not increase awake time, compared to placebo (side effects comparison), a higher smoking rate among modafinil participants was not simply a function of increased awake time. Further, we found no effect of modafinil among sub-groups of participants differentiated by baseline levels of alcohol consumption and ADHD symptoms. This result converges with a recent review of clinical trials of modafinil for sleep disorders, various psychiatric conditions, and cognitive function, which indicated little variation in treatment response across sub-groups of study participants (Minzenberg and Carter, 2007). These findings may have important clinical implications, not only for medication development for nicotine dependence, but also for using modafinil for approved indications among patients who smoke.

The results of this study are consistent with some prior animal and human laboratory studies of medications with stimulant-like effects. For example, methylphenidate increases the rate of nicotine self-administration in rodents (Wooters et al., 2007) and ad-lib smoking in human laboratory studies (Rush et al., 2005; Vansickel et al., 2007). In the present study, modafinil may have led to poor quit rates by increasing negative mood and withdrawal symptoms which increase smoking rate and the risk for smoking relapse (Etter, 2005; Lerman et al., 2002). Our findings are also consistent with two recent within-subject placebo-controlled investigations which reported an increase in negative affect, as measured by the PANAS, following modafinil administration (Sofuoglu et al., 2008; Taneja et al., 2007). Our findings and those of previous studies may be due to the inclusion of items in the negative affect subscale that may be particularly sensitive to modafinil’s effects (e.g., jittery, nervous). Collectively, these data suggest that medications that increase arousal may have negative effects on mood and, thus, may not be useful therapeutics for the treatment of nicotine dependence.

The results of this study also suggest that treatment of drugs of abuse, such as cocaine and nicotine, which share common neurobiological underpinnings (Nestler, 2005), may require very different treatment approaches. Despite the potential efficacy of modafinil for cocaine dependence (Dackis et al., 2005), modafinil does not appear efficacious for nicotine dependence – even though there is a high rate of comorbidity of these two conditions (Lai et al., 2000). Such a finding, however, is not uncommon. For instance, the opioid antagonist naltrexone effectively treats alcohol and opioid dependence (Modesto-Lowe and Van Kirk, 2002), but is not efficacious for the treatment of nicotine dependence (David et al., 2006; Ray et al., 2006).

Perhaps most importantly, the results of this trial suggest that clinicians should exercise caution when prescribing modafinil for various medical and psychiatric conditions. Modafinil is FDA approved to treat sleep disorders (Ballon and Feifel, 2006), and it has been evaluated as a treatment for cocaine dependence (Dackis et al., 2005) and ADHD (Lindsay et al., 2006), as a treatment for negative symptoms among schizophrenics (Pierre et al., 2007), and as an adjunctive medication to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for treating depression (Thase et al., 2006). Importantly, the prevalence rates of tobacco use among those diagnosed with ADHD (Fuemmeler et al., 2007), schizophrenia (Poirier et al., 2002), and depression (Poirier et al., 2002) exceed the rate of smoking in the general population, and smoking may be a risk factor for sleep disorders (Khoo et al., 2004). Thus, modafinil treatment in these patients may inhibit attempts to quit smoking or reduce cigarette consumption in these patient populations.

While the present findings offer important information concerning the use of modafinil, study limitations should be acknowledged. First, the present study used healthy smokers who volunteered for a smoking cessation program. We could locate no data concerning the effects of stimulant-like medications on smoking behavior among individuals with other psychiatric or medical conditions. Thus, it is unclear whether modafinil would inhibit reductions in cigarette consumption among individuals with other psychiatric or medical conditions who are smokers trying to quit. Second, the present study used a 200mg dose of modafinil, whereas some studies with modafinil have used a 400mg dose. The decision to use a 200mg dose was made to reduce the potential rate of participant attrition due to adverse drug-related side effects, namely insomnia, which was observed during a pilot study phase. However, based on the increased abstinence symptoms with the 200mg dose, compared to placebo, one would not expect better outcomes with a higher dose. Third, there was a significant difference in abstinence rates across treatment site. We examined possible explanations for this effect (e.g., FTND scores or baseline smoking rates) but could not detect any differences across site that may account for this effect. Regardless, there was no effect of modafinil on abstinence rates when the sites were examined separately and all analyses included treatment site as a covariate. Fourth, it may be plausible that the blinding was not effective since, when we asked participants at the end of the trial about which arm they believed they were selected for, we found a significant relationship between treatment arm and belief about treatment arm randomization (χ2[2] = 11.89, p <.05). Participants randomized to modafinil were more likely to say they received modafinil (vs. placebo or don’t know), whereas participants randomized to placebo were more likely to indicate that they received placebo (vs. modafinil or don’t know). However, considering that a violation of the study blind would increase a possible treatment effect, a violation of study blind is not likely to explain the null results found here. Finally, 39 participants (25%) were not reached for the week 8 assessment and, thus, were considered to be smokers, as is common practice in smoking cessation trials. While this may bias results since these individuals are considered smokers in the analysis, there was no difference in this rate across treatment arms. Further, the rate of loss compares to a recent smoking cessation trial with varenicline (Jorenby et al., 2006).

Therefore, overall, the present data do not support the efficacy of modafinil as a treatment for nicotine dependence. To the contrary, modafinil may inhibit reductions in cigarette consumption rates among smokers trying to quit smoking and may increase withdrawal and negative mood symptoms during the treatment phase. Additional research is warranted to assess the possible untoward effects of medications that have stimulant-like effects among those treated for psychiatric or medical conditions aside from nicotine dependence, while the need to identify novel treatments for nicotine dependence remains as a critical public health priority.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ballon JS, Feifel D. A systematic review of modafinil: Potential clinical uses and mechanisms of action. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2006;67:554–566. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranski JV, Pigeau R, Dinich P, Jacobs I. Effects of modafinil on cognitive and meta-cognitive performance. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 2004;19:323–332. doi: 10.1002/hup.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Murphy KR. Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Clinical Workbook. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Burgess ES, Sales SD, Whiteley JA, Evans DM, Miller IW. Reliability and validity of a smoking timeline follow-back interview. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 1998;12:101–112. [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Higgins ST, Hughes JR, Bickel WK. Nicotine and caffeine use in cocaine-dependent individuals. J. Sub. Abuse. 1993;5:117–130. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(93)90056-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill K, Stead LF, Lancaster T. Nicotine receptor partial agonists for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2007:CD006103. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006103.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. Cigarette smoking among adults. United States-MMWR. 2004;54:1121–1124. [Google Scholar]

- Dackis CA, Kampman KM, Lynch KG, Pettinati HM, O'Brien CP. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of modafinil for cocaine dependence. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:205–211. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David S, Lancaster T, Stead LF, Evins AE. Opioid antagonists for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2006:CD003086. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003086.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etter JF. A self-administered questionnaire to measure cigarette withdrawal symptoms: The Cigarette Withdrawal Scale. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2005;7:47–57. doi: 10.1080/14622200412331328501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuemmeler BF, Kollins SH, McClernon FJ. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms predict nicotine dependence and progression to regular smoking from adolescence to young adulthood. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2007;32:1203–1213. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney M, Spealman R. Controversies in translational research: drug self-administration. Psychopharmacology. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1079-x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: A revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br. J. Addict. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Hatsukami DK, Pickens RW, Krahn D, Malin S, Luknic A. Effect of nicotine on the tobacco withdrawal syndrome. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1984;83:82–87. doi: 10.1007/BF00427428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Keely JP, Niaura RS, Ossip-Klein DJ, Richmond RL, Swan GE. Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: issues and recommendations. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2003;5:13–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Stead LF, Lancaster T. Antidepressants for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2007:CD000031. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000031.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorenby DE, Hays JT, Rigotti NA, Azoulay S, Watsky EJ, Williams KE, Billing CB, Gong J, Reeves KR. Efficacy of varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs. placebo or sustained-release bupropion for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296:56–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoo SM, Tan WC, Ng TP, Ho CH. Risk factors associated with habitual snoring and sleep-disordered breathing in a multi-ethnic Asian population: a population-based study. Respir. Med. 2004;98:557–566. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killen JD, Fortmann SP. Craving is associated with smoking relapse: findings from three prospective studies. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1997;5:137–142. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.5.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai S, Lai H, Page JB, McCoy CB. The association between cigarette smoking and drug abuse in the United States. J. Addict. Dis. 2000;19:11–24. doi: 10.1300/J069v19n04_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman C, Roth D, Kaufmann V, Audrain J, Hawk L, Liu A, Niaura R, Epstein L. Mediating mechanisms for the impact of bupropion in smoking cessation treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;67:219–223. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay SE, Gudelsky GA, Heaton PC. Use of modafinil for the treatment of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Ann. Pharmacother. 2006;40:1829–1833. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makris AP, Rush CR, Frederich RC, Kelly TH. Wake-promoting agents with different mechanisms of action: comparison of effects of modafinil and amphetamine on food intake and cardiovascular activity. Appetite. 2004;42:185–195. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menza MA, Kaufman KR, Castellanos A. Modafinil augmentation of antidepressant treatment in depression. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2000;61:378–381. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v61n0510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minzenberg MJ, Carter CS. Modafinil: A review of neurochemical actions and effects on cognition. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007:1–26. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell PB. Novel French antidepressants not available in the United States. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1995;31:509–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modesto-Lowe V, Van Kirk J. Clinical uses of naltrexone: a review of the evidence. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2002;10:213–227. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.10.3.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ. Is there a common molecular pathway for addiction? Nat. Neurosci. 2005;8:1445–1449. doi: 10.1038/nn1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierre JM, Peloian JH, Wirshing DA, Wirshing WC, Marder SR. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of modafinil for negative symptoms in schizophrenia. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2007;68:705–710. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirier MF, Canceil O, Bayle F, Millet B, Bourdel MC, Moatti C, Olie JP, Attar-Levy D. Prevalence of smoking in psychiatric patients. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol. Psychiatry. 2002;26:529–537. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(01)00304-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. The CES-D scale: A new self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychological Measure. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Ray R, Jepson C, Patterson F, Strasser A, Rukstalis M, Perkins K, Lynch KG, O'Malley S, Berrettini WH, Lerman C. Association of OPRM1 A118G variant with the relative reinforcing value of nicotine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;188:355–363. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0504-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush CR, Higgins ST, Vansickel AR, Stoops WW, Lile JA, Glaser PE. Methylphenidate increases cigarette smoking. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;181:781–789. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0021-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silagy C, Lancaster T, Stead L, Mant D, Fowler G. Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2004:CD000146. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000146.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofuoglu M, Waters AJ, Mooney M. Modafinil and nicotine interactions in abstinent smokers. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 2008;23:21–30. doi: 10.1002/hup.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco Subcommittee on Biochemical Verification. Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2001:149–159. doi: 10.1080/14622200210123581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taneja I, Haman K, Shelton RC, Robertson D. A randomized, double-blind, crossover trial of modafinil on mood. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27:76–79. doi: 10.1097/jcp.0b013e31802eb7ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thase ME, Fava M, DeBattista C, Arora S, Hughes RJ. Modafinil augmentation of SSRI therapy in patients with major depressive disorder and excessive sleepiness and fatigue: a 12-week, open-label, extension study. CNS Spectr. 2006;11:93–102. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900010622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner DC, Robbins TW, Clark L, Aron AR, Dowson J, Sahakian BJ. Cognitive enhancing effects of modafinil in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;165:260–269. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1250-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vansickel AR, Stoops WW, Glaser PE, Rush CR. A pharmacological analysis of stimulant-induced increases in smoking. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;193:305–313. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0786-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh JK, Randazzo AC, Stone KL, Schweitzer PK. Modafinil improves alertness, vigilance, and executive function during simulated night shifts. Sleep. 2004;27:434–439. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scale. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wooters TE, Neugebauer NM, Rush CR, Bardo MT. Methylphenidate enhances the abuse-related behavioral effects of nicotine in rats: Intravenous self-administration, drug discrimination, and locomotor cross-sensitization. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1137–1148. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]