Abstract

An emerging concept in cancer biology is that a rare population of cancer stem cells exists among the heterogeneous cell mass that constitutes a tumor. This concept is best understood in human myeloid leukemia. Normal and malignant hematopoietic stem cell functions are defined by a common set of critical stemness genes that regulate self-renewal and developmental pathways. Several stemness factors, such as Notch or telomerase, show differential activation in normal hematopoietic versus leukemia stem cells. These differences could be exploited therapeutically even with drugs that are already in clinical use for the treatment of leukemia. The translation of novel and existing leukemic stem cell – directed therapies into clinical practice, however, will require changes in clinical trial design and the inclusion of stem cell biomarkers as correlative end points.

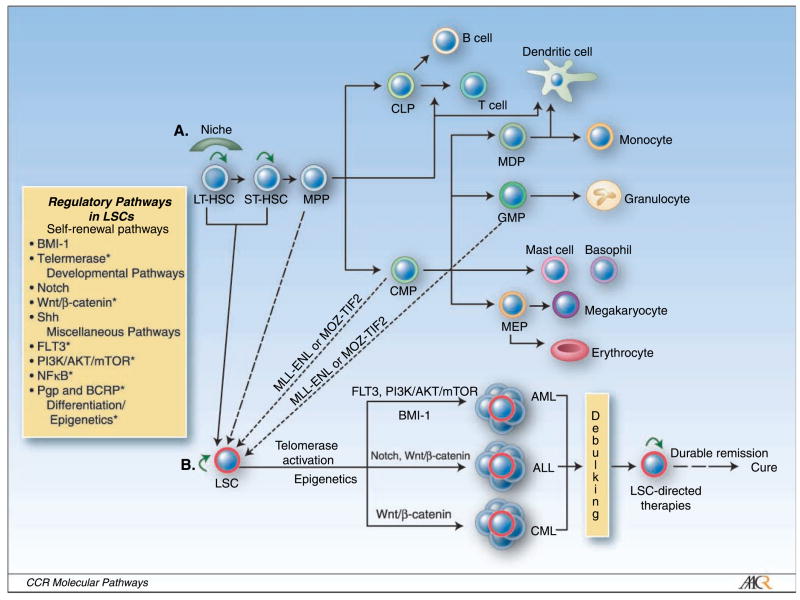

The hallmarks of hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) are their ability to self-renew and to develop into multiple lineages through differentiation (Fig. 1A; ref. 1). HSCs can be functionally defined as either long-term (LT-HSC) or short-term (ST-HSC) repopulating stem cells by their capacity to provide life-long or transient hematopoiesis. Furthermore, LT-HSCs primarily reside in bone marrow niches, whereas ST-HSC may be mobilized (Fig. 1A; ref. 2). Strict regulation of HSCs is crucial to ensure maintenance of regenerating cells without abnormal outgrowth of immature cells. Dysregulated expansion and growth of HSCs is likely to play a critical role in leukemogenesis (Fig. 1A and B; refs. 3, 4).

Fig. 1.

A, the hierarchy of the hematopoietic system. LT-HSCs reside in a niche and asymmetrically divide into ST-HSCs and/or self-renew (green arrow). ST-HSCs exiting the niche actively undergo expansion and give rise to multipotent progenitors (MPP) that lack self-renewal potential. Common lymphoid progenitors (CLP) and common myeloid progenitors (CMP) arise from multipotent progenitors. Common lymphoid progenitors give rise to T cells and B cells. CMPs give rise to granulocyte/macrophage progenitors (GMP), megakaryocyte/erythroid progenitors (MEP), and mast cell and basophil progenitors, as well as macrophage and dendritic cell progenitors (MDP). B, leukemia stem cell hierarchy. LT-HSCs and ST-HSCs, as well as multipotent progenitors, CMPs, and GMPs, can potentially become LSCs with preserved self-renewal capacity. LSCs up-regulate telomerase activity and express stemness factors that are associated with self-renewal, developmental, and growth signaling pathways (see box). LSCs can differentiate into multiple types of leukemia via distinct gene activation. Conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy can only achieve tumor debulking by killing mature leukemia cells. LSCs are resistant to conventional treatment strategies and will often repopulate, resulting in recurrence of the disease. LSC-directed therapies (see Table 1), when given together with debulking agents, are hoped to yield durable remissions and ultimately cures. *, LSC targets that can be treated with drugs.

The existence of leukemic stem cells (LSC) was proposed more than three decades ago following the development of clonogenic growth assays with the capacity for clonal growth of leukemia in vitro. There was no definitive proof of LSCs, however, until Dick and colleagues showed that the engraftment of nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient (NOD/SCID) mice with primary acute myeloid leukemia (AML) samples could only be accomplished using cells that were phenotypically similar to normal HSCs by expressing CD34 and lacking markers of lineage commitment such as CD38 (5). Furthermore, these primitive cells produced leukemic blasts within engrafting animals that phenotypically matched each patient’s original AML. These results suggested that the cellular organization of AML is similar to normal hematopoiesis with immature stem cells that have clonogenic growth potential giving rise to differentiated cells with little long-term growth potential. Importantly, LSCs could be isolated and transplanted into secondary recipients, showing that they had the capacity to self-renew (5). Due to a high degree of phenotypic and functional similarity, it has been hypothesized that most human leukemias arise from transformation of HSCs (Fig. 1A; refs. 5, 6). Conversely, recent studies have shown that transduction of the MLL-ENL or MOZ-TIF2 fusion genes into HSCs, common myeloid progenitors, and granulocyte-macrophage progenitors resulted in the identical leukemia (4, 7). These results indicate that committed progenitors with little long-term replicative potential may acquire self-renewal capability and transform into LSCs (Fig. 1A and B). It is unclear, however, what proportion of human myeloid leukemias arise from committed progenitors or by a single oncogenic event such as MLL-ENL and MOZ-TIF2, and whether these models can be useful in identifying key regulatory pathways that represent therapeutic targets.

In the following sections of this review, we will therefore highlight regulatory pathways of LSCs with validated and treatable LSC targets (Table 1).

Table 1.

Experimental and available LSC-directed therapies

| Target | Agents | Leukemic type | Phase of clinical development | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD33 | Gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg)* | AML | In clinical use | (55, 54) |

| Telomeres and telomerase | Arsenic trioxide (Trisenox)* | APL | In clinical use | (17, 18) |

| GRN163L (hTERC inhibitor) | CLL | I/II | (19) Recruiting: NCT00124189 | |

| hTERT vaccine (TVAX) | Hematologic malignancies | I | (20, 21) | |

| Epigenetics (BMI-1) | Vorinostat (Zolinza)† | AML | II | Recruiting: NCT00305773 |

| Azacitidine (Vidaza)† | CML | II | (56) | |

| Decitabine (Dacogen)† | AML, ALL, CML | I | (57) | |

| FLT3 | CEP701 (Lestaurtinib) | AML | II | (45) |

| mTOR | PKC412 everolimus | AML hematologic malignancies | II | (58) |

| Temsirolimus | CML and CLL | I/II | (49) | |

| Rapamycin† | AML | I and II | Recruiting: NCT00101088, NCT00290472 | |

| Preclinical | (48) | |||

| P-Glycoprotein | Zosuquidar | Advance malignancies | I/II | Recruiting: NCT00129168, NCT00233909 |

| I | (53) | |||

| γ-Secretase (Notch) | MK-0752 | T-cell ALL and other leukemia | I | (26) |

| NF-κB | NPI-0052 (salinosporamides A) | Hematologic malignancies: NHL, CLL, and Ph+ ALL | I | (35, 59) |

| TDZD-8 (parthenolide) | Leukemia | Preclinical | (36) |

Abbreviations: APL, acute promyelocytic leukemia; CLL; chronic lymphocytic leukemia; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; NHL, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Food and Drug Administration approved for treatment of leukemia.

Food and Drug Administration approved for different indication.

Clinical Translational Advances

Regulatory pathways in LSCs

HSCs and LSCs share common features: self-renewal, the capacity to differentiate, resistance to apoptosis, and limitless proliferative potential. The pathways regulating these functional properties can be categorized into self-renewal, developmental, and miscellaneous pathways, each of which is governed by a distinct set of critical genes that have emerged from molecular profiling and can be associated with “stemness” (Fig. 1).

Self-renewal pathways

BMI

BMI-1 is a polycomb group (PcG) RING-finger protein that has an essential function in the maintenance of HSCs and LSCs. The BMI-1 gene was originally identified as an oncogene inducing B-cell or T-cell leukemia. Recent experiments with Bmi-1−/− mice showed that leukemic (AML) stem/progenitor cells lacking Bmi-1 were unable to engraft and proliferate and displayed signs of differentiation and apoptosis. Conversely, the reconstitution of the Bmi-1 gene was found to completely abrogate these proliferative defects (8). Functionally, BMI-1 forms a heterodimeric complex with another PcG protein, Ring1b. PcG complexes bind to chromatin and initiate and maintain gene repression, which is thought to be mediated by methylation, deacetylation, and ubiquitination of core histones. BMI-1 and Ring1b reconstitute an ubiquitin E3 ligase activity with histone H2A as their ubiquitination substrate (9). Thus, inhibitors of methylation, histone deacetylase inhibitors, or inhibitors of the ubiquitin-proteasome system could be exploited as anti–BMI-1 strategies in LSCs. Interestingly, a recent study showed that BMI-1 localization to PcG bodies can be interdicted by the DNA methylation inhibitor 5-azacytidine (Table 1; ref. 10). Further studies are required to assess the capacity of 5-azacytidine to modulate BMI-1 as well as the role of BMI-1 (and epigenetics) in LSCs.

Telomerase

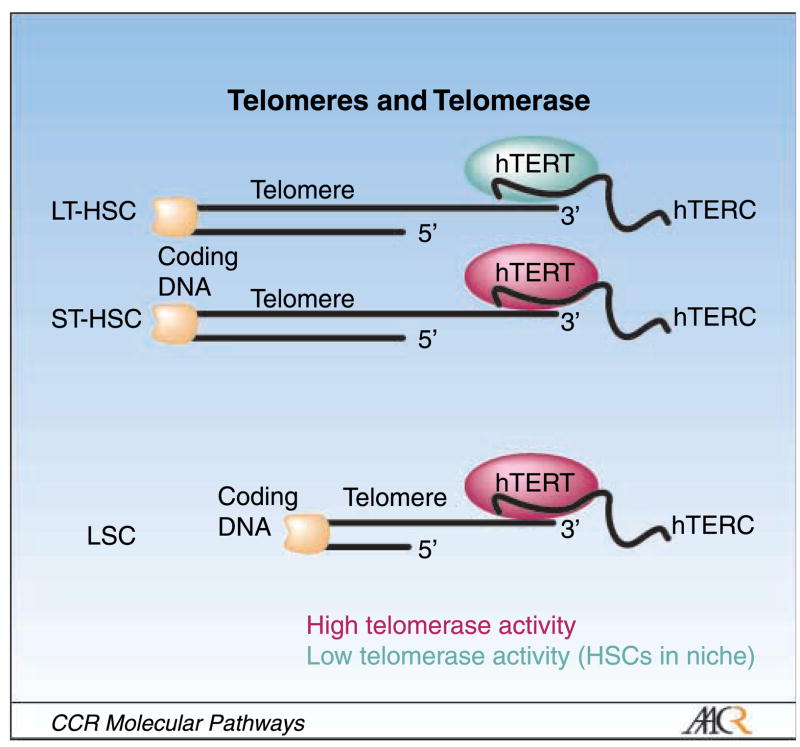

Telomerase is a ribonucleoprotein enzyme composed of the human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) and the human telomerase RNA component (hTERC), which synthesizes telomeric repeats onto chromosomal ends and thereby prevents replicative senescence (11). Although stem cells in general possess limitless proliferative capacity and long telomeres, LT-HSCs are unable to prevent telomere shortening on serial transplantation because of low levels of telomerase expression. However, telomerase expression is up-regulated with cell cycle activation, and as a consequence, expression levels are higher in ST-HSCs or more committed progenitors (reviewed in refs. 12, 13; Fig. 2). These data are consistent with recent findings in genetically engineered mouse models, which have shown that overexpression of TERT promotes mobilization of epidermal stem cells out of their niches, leading to stem cell proliferation in vitro and excessive hair growth in vivo (14, 15), whereas short telomeres cause stem cell failure and limit tissue renewal capacity (16). In human chronic myeloid leukemia, LSCs and HSCs were comparatively analyzed for telomere length, and it was found that telomeres in LSCs were significantly shorter than in HSCs and that telomerase activity in LSCs was high (Fig. 2; ref. 12, 13). This differential in telomere length and telomerase activity between HSCs and LSCs (Fig. 2) opens avenues for exploiting telomerase-directed treatments as stem cell therapeutics. Drugs with telomerase-modulating properties that are already in clinical trials in leukemia include arsenic trioxide, the hTERC antisense oligonucleotide GRN163L, and hTERT vacccines (Table 1.; refs. 17–21).

Fig. 2.

Telomere and telomerase status in normal and malignant hematopoietic cells. LSCs are distinct from LT-HSCs and ST-HSCs. LT-HSCs have relatively long telomeres, but low telomerase activity, which cannot maintain telomere length, and thus LT-HSC telomeres shorten when the cells replicate. ST-HSCs have long telomeres and up-regulate telomerase, enabling them to actively amplify. LSCs have high telomerase activity but short telomeres that essentially require maintenance by telomerase, thereby providing a target for therapeutic intervention.

Developmental pathways

Notch signaling pathway

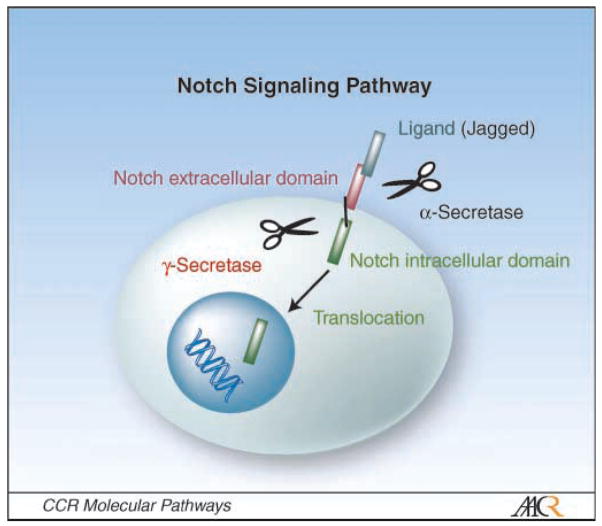

The Notch signaling pathway regulates the specification of cell fate and differentiation (22). Four Notch transmembrane heterodimeric receptors (Notch 1-Notch 4) and five ligands are known. The ligands Jagged 1, Jagged 2, and Δ1 to Δ3 can initiate Notch signaling by releasing the intracellular domain of the receptor (Notch-IC) through proteolytic cleavage involving α-secretase and γ-secretase (Fig. 3). Notch-IC then enters the nucleus and induces the transcription of Notch-responsive genes (22, 23). Overexpression of constitutively active Notch 1 in HSCs results in a complete inhibition of B-cell development. In T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Notch 1 is found to be constitutively activated in patients with the t(7:9) chromosomal translocation. This involves high expression of a constitutively activated form of Notch 1 by the promoter and enhancer elements regulating the β-chain of the T-cell receptor (Fig. 1B). Although this distinctive chromosomal translocation is found in <1% of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cases, >50% of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients carry somatic activating point mutations of Notch 1 (24, 25). Several Notch inhibitors are in clinical development for the treatment of cancer, including MK-0752, a γ-secretase inhibitor in phase I trials in patients with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and other leukemias (Table 1; ref. 26).

Fig. 3.

Notch signaling pathway. Notch ligands such as Jagged 1/2 bind to the extracellular domain of Notch receptors. Cleavage of the Notch receptors by α-secretase and γ-secretase releases the Notch intracellular domain, which translocates into the nucleus, resulting in transcription activation. γ-Secretase has been validated as a therapeutic target (see Table 1).

Other pathways

Other regulators of developmental pathways that play a role in leukemia include Wnt/β-catenin signaling (Fig. 1A and B; refs. 1, 27). The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is important in T-cell development by providing proliferative signals to most immature thymocytes (28). Similar to Notch, Wnt is involved in the development of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Furthermore, it has been implicated in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and the progression of chronic myeloid leukemia to blast crisis (Fig. 1B; refs. 29, 30). Inhibitors of Wnt have been described; e.g, the anti-inflammatory drug R-etodolac has been shown to diminish Wnt/β-catenin signaling at concentrations that increased apoptosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells (30).

Miscellaneous targets

Nuclear factor κB

Nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) is a transcription factor that has antiapoptotic activity and is activated in many tumor types including lymphoid leukemia (31–34). Unlike in HSCs that show little NF-κB activity, however, NF-κB is constitutively activated in LSCs (Fig. 1A; ref. 34). This difference is currently exploited in clinical studies. A novel proteosome inhibitor, salinosporamides A, which inhibits NF-κB by stabilizing its suppressor IκB, and parthenolide, a natural product that can directly target NF-κB, are being investigated as LSC treatments (Table 1; refs. 35, 36).

FLT3

Under normal conditions, FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) receptor is expressed in CD34+ short-term reconstituting hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (37–39). FLT3 mutations are among the most common genetic abnormalities in AML and are present in ~30% of all cases. It is associated with poor prognosis and increased relapse rates (39–43). Recent data showed that the FLT3 internal tandem duplication mutation is present in CD34+/CD34− LSCs (Fig. 1A; ref. 44. Furthermore, inhibition of FLT3 signaling with CEP701 resulted in failure of FLT3 internal tandem duplication LSCs to engraft in NOD/SCID mice. Currently, several FLT3 inhibitors, including CEP701 and PKC412, are in phase II clinical trials in AML (Table 1; refs. 45, 46).

Phosphatidylinositide-3-kinase/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin

The phosphatidylinositide-3-kinase/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway is constitutively activated in most AMLs and is essential for AML blast survival (47). Unlike in short-term repopulating leukemia cells, the activation of mTOR is required in LT-HSCs, suggesting an essential role of this pathway in LSCs (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, coadministration of the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin was found to potentiate the ability of etoposide to prevent the engraftment of AML cells in NOD/SCID mice (48). Three mTOR inhibitors, rapamycin, temsirolimus, and everolimus, are under clinical investigation in leukemia, albeit not as LSC targeting strategies (Table 1; refs. 48, 49).

Cell-surface proteins

An intriguing property of normal and LSCs is the expression of high levels of the drug efflux pumps P-glycoprotein (ABCB1) and breast cancer resistance protein (ABCG2; ref. 50). Whereas the ABC transporters provide a mechanism of self-protection in HSCs, they are involved in multidrug resistance of leukemia to a wide variety of cytotoxic agents. P-glycoprotein inhibition using cyclosporine A was found to enhance clinical outcomes in combination with standard cytotoxic chemotherapy in poor-risk patients with AML (51). Subsequent clinical studies with the P-glycoprotein inhibitor valspodar (PSC-833), however, failed to show benefit (52). The P-glycoprotein inhibitor zosuquidar is currently in clinical trials in leukemias in combination with standard cytotoxic agents. Breast cancer resistance protein inhibitors will likely be more selective and effective, but are still in preclinical development (Table 1; refs. 50, 53).

Another cell-surface molecule that could be exploited as a LSC target is CD33. Bonnet et al. have shown that leukemia-initiating cells in NOD/SCID mice express CD33 and proposed that anti-CD33 antibodies might be useful to direct cytotoxic drugs to LSCs. Mylotarg is such a preparation that is Food and Drug Administration approved for clinical use in AML (Table 1; refs. 54, 55).

Clinical Implications of LSC-Directed Therapies

Initial evidence for the existence of LSCs suggested that these highly clonogenic cells must be eradicated to achieve durable remission or cure (6). However, the molecular understanding to identify relevant pathways and produce novel targeted therapeutics was lacking. In current clinical practice, standard anticancer agents are still used with the intent to kill the bulk tumor mass. However, most of these fail to eradicate cancer stem cells, resulting in disease relapse. Because cancer stem cells are rare, it is likely that novel clinical trial designs must be used that consider LSC biology and the potential of delayed responses. These strategies may also require combining different classes of agents to target both mature cells and LSCs (Fig. 1B; Table 1). For example, differentiated leukemic cells that make up the bulk of the disease could be treated with conventional chemotherapy to alleviate patients’ symptoms. Subsequently, when tumor burden is low, LSC-directed treatments should be initiated (Fig. 1B). To ultimately prove the validity and efficacy of LSC tailored chemotherapy regimens, stem cell markers must be used to investigate the effects of LSC-targeting agents on this rare cell population.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Takeo Nakanishi for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful comments.

Grant support: University of Maryland Cancer Research Grant through the Maryland Cigarette Restitution Fund Program.

References

- 1.Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Weissman IL. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001;414:105–11. doi: 10.1038/35102167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ho AD. Kinetics and symmetry of divisions of hematopoietic stem cells. Exp Hematol. 2005;33:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonnet D. Normal and leukaemic stem cells. Br J Haematol. 2005;130:469–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cozzio A, Passegue E, Ayton PM, et al. Similar MLL-associated leukemias arising from self-renewing stem cells and short-lived myeloid progenitors. Genes Dev. 2003;17:3029–35. doi: 10.1101/gad.1143403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonnet D, Dick JE. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat Med. 1997;3:730–7. doi: 10.1038/nm0797-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ravandi F, Estrov Z. Eradication of leukemia stem cells as a new goal of therapy in leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:340–4. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huntly BJ, Shigematsu H, Deguchi K, et al. MOZ-TIF2, but not BCR-ABL, confers properties of leukemic stem cells to committed murine hematopoietic progenitors. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:587–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lessard J, Sauvageau G. Bmi-1 determines the proliferative capacity of normal and leukaemic stem cells. Nature. 2003;423:255–60. doi: 10.1038/nature01572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buchwald G, van der Stoop P, Weichenrieder O, et al. Structure and E3-ligase activity of the Ring-Ring complex of polycomb proteins Bmi1 and Ring1b. EMBO J. 2006;25:2465–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hernandez-Munoz I, Taghavi P, Kuijl C, Neefjes J, van Lohuizen M. Association of BMI1 with polycomb bodies is dynamic and requires PRC2/EZH2 and the maintenance DNA methyltransferase DNMT1. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:11047–58. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.24.11047-11058.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blasco MA. Telomeres and human disease: ageing, cancer and beyond. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:611–22. doi: 10.1038/nrg1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brummendorf TH, Balabanov S. Telomere length dynamics in normal hematopoiesis and in disease states characterized by increased stem cell turnover. Leukemia. 2006;20:1706–16. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiyama E, Hiyama K. Telomere and telomerase in stem cells. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:1020–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarin KY, Cheung P, Gilison D, et al. Conditional telomerase induction causes proliferation of hair follicle stem cells. Nature. 2005;436:1048–52. doi: 10.1038/nature03836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flores I, Cayuela ML, Blasco MA. Effects of telomerase and telomere length on epidermal stem cell behavior. Science. 2005;309:1253–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1115025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hao LY, Armanios M, Strong MA, et al. Short telomeres, even in the presence of telomerase, limit tissue renewal capacity. Cell. 2005;123:1121–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Estey E, Garcia-Manero G, Ferrajoli A, et al. Use of all-trans retinoic acid plus arsenic trioxide as an alternative to chemotherapy in untreated acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood. 2006;107:3469–73. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller WH, Jr, Schipper HM, Lee JS, Singer J, Waxman S. Mechanisms of action of arsenic trioxide. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3893–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dikmen ZG, Gellert GC, Jackson S, et al. In vivo inhibition of lung cancer by GRN163L: a novel human telomerase inhibitor. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7866–73. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vonderheide RH, Domchek SM, Schultze JL, et al. Vaccination of cancer patients against telomerase induces functional antitumor CD8+ T lymphocytes. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:828–39. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0620-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Danet-Desnoyers GA, Luongo JL, Bonnet DA, Domchek SM, Vonderheide RH. Telomerase vaccination has no detectable effect on SCID-repopulating and colony-forming activities in the bone marrow of cancer patients. Exp Hematol. 2005;33:1275–80. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Rand MD, Lake RJ. Notch signaling: cell fate control and signal integration in development. Science. 1999;284:770–6. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lehar SM, Dooley J, Farr AG, Bevan MJ. Notch ligands Δ1 and Jagged1 transmit distinct signals to T-cell precursors. Blood. 2005;105:1440–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weng AP, Ferrando AA, Lee W, et al. Activating mutations of NOTCH1 in human T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Science. 2004;306:269–71. doi: 10.1126/science.1102160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huntly BJ, Gilliland DG. Leukaemia stem cells and the evolution of cancer-stem-cell research. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:311–21. doi: 10.1038/nrc1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deangelo DJ, Stone RM, Silverman LB, et al. A phase I clinical trial of the notch inhibitor MK-0752 in patients with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (T-ALL) and other leukemias. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:6585. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pardal R, Clarke MF, Morrison SJ. Applying the principles of stem-cell biology to cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:895–902. doi: 10.1038/nrc1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Staal FJ, Clevers HC. WNT signalling and haematopoiesis: a WNT-WNT situation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:21–30. doi: 10.1038/nri1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weerkamp F, van Dongen JJ, Staal FJ. Notch and Wnt signaling in T-lymphocyte development and acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2006;20:1197–205. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu D, Zhao Y, Tawatao R, et al. Activation of the Wnt signaling pathway in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3118–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308648100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang W, Abbruzzese JL, Evans DB, et al. The nuclear factor-κB RelA transcription factor is constitutively activated in human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:119–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shattuck-Brandt RL, Richmond A. Enhanced degradation of I-κBα contributes to endogenous activation of NF-κB in Hs294T melanoma cells. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3032–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kordes U, Krappmann D, Heissmeyer V, Ludwig WD, Scheidereit C. Transcription factor NF-κB is constitutively activated in acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Leukemia. 2000;14:399–402. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guzman ML, Neering SJ, Upchurch D, et al. Nuclear factor-κB is constitutively activated in primitive human acute myelogenous leukemia cells. Blood. 2001;98:2301–7. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.8.2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller CP, Ban K, Dujka ME, et al. NPI-0052, a novel proteasome inhibitor, induces caspase-8 and ROS-dependent apoptosis alone and in combination with HDAC inhibitors in leukemia cells. Blood. 2007;110:267–77. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-013128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jordan CT. The leukemic stem cell. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2007;20:13–8. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sitnicka E, Buza-Vidas N, Larsson S, et al. Human CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells capable of multiline-age engrafting NOD/SCID mice express flt3: distinct flt3 and c-kit expression and response patterns on mouse and candidate human hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2003;102:881–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lyman SD, Jacobsen SE. c-kit ligand and Flt3 ligand: stem/progenitor cell factors with overlapping yet distinct activities. Blood. 1998;91:1101–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parcells BW, Ikeda AK, Simms-Waldrip T, Moore TB, Sakamoto KM. FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 in normal hematopoiesis and acute myeloid leukemia. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1174–84. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levis M, Small D. FLT3: ITDoes matter in leukemia. Leukemia. 2003;17:1738–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gilliland DG, Griffin JD. The roles of FLT3 in hematopoiesis and leukemia. Blood. 2002;100:1532–42. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-02-0492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kottaridis PD, Gale RE, Frew ME, et al. The presence of a FLT3 internal tandem duplication in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) adds important prognostic information to cytogenetic risk group and response to the first cycle of chemotherapy: analysis of 854 patients from the United Kingdom Medical Research Council AML 10 and 12 trials. Blood. 2001;98:1752–9. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.6.1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schnittger S, Schoch C, Dugas M, et al. Analysis of FLT3 length mutations in 1003 patients with acute myeloid leukemia: correlation to cytogenetics, FAB subtype, and prognosis in the AMLCG study and usefulness as a marker for the detection of minimal residual disease. Blood. 2002;100:59–66. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Levis M, Murphy KM, Pham R, et al. Internal tandem duplications of the FLT3 gene are present in leukemia stem cells. Blood. 2005;106:673–80. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Knapper S, Burnett AK, Littlewood T, et al. A phase 2 trial of the FLT3 inhibitor lestaurtinib (CEP701) as first-line treatment for older patients with acute myeloid leukemia not considered fit for intensive chemotherapy. Blood. 2006;108:3262–70. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-015560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith BD, Levis M, Beran M, et al. Single-agent CEP-701, a novel FLT3 inhibitor, shows biologic and clinical activity in patients with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2004;103:3669–76. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao S, Konopleva M, Cabreira-Hansen M, et al. Inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase dephosphorylates BAD and promotes apoptosis in myeloid leukemias. Leukemia. 2004;18:267–75. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu Q, Thompson JE, Carroll M. mTOR regulates cell survival after etoposide treatment in primary AML cells. Blood. 2005;106:4261–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yee KW, Zeng Z, Konopleva M, et al. Phase I/II study of the mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor everolimus (RAD001) in patients with relapsed or refractory hematologic malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5165–73. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Plasschaert SL, Van Der Kolk DM, De Bont ES, et al. Breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) in acute leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2004;45:649–54. doi: 10.1080/10428190310001597928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.List AF, Kopecky KJ, Willman CL, et al. Benefit of cyclosporine modulation of drug resistance in patients with poor-risk acute myeloid leukemia: a Southwest Oncology Group study. Blood. 2001;98:3212–20. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.12.3212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baer MR, George SL, Dodge RK, et al. Phase 3 study of the multidrug resistance modulator PSC-833 in previously untreated patients 60 years of age and older with acute myeloid leukemia: Cancer and Leukemia Group B Study 9720. Blood. 2003;100:1224–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fracasso PM, Goldstein LJ, de Alwis DP, et al. Phase I study of docetaxel in combination with the P-glycoprotein inhibitor, zosuquidar, in resistant malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:7220–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Taussig DC, Pearce DJ, Simpson C, et al. Hematopoietic stem cells express multiple myeloid markers: implications for the origin and targeted therapy of acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2005;106:4086–92. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sievers EL, Larson RA, Stadtmauer EA, et al. Efficacy and safety of gemtuzumab ozogamicin in patients with CD33-positive acute myeloid leukemia in first relapse. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3244–54. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.13.3244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Issa JP, Gharibyan V, Cortes J, et al. Phase II study of low-dose decitabine in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia resistant to imatinib mesylate. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3948–56. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.11.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Issa JP, Garcia-Manero G, Giles FJ, et al. Phase 1 study of low-dose prolonged exposure schedules of the hypomethylating agent 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (decitabine) in hematopoietic malignancies. Blood. 2004;103:1635–40. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stone RM, DeAngelo DJ, Klimek V, et al. Patients with acute myeloid leukemia and an activating mutation in FLT3 respond to a small-molecule FLT3 tyrosinekinase inhibitor, PKC412. Blood. 2005;105:54–60. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-0891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ruiz S, Krupnik Y, Keating M, et al. The proteasome inhibitor NPI-0052 is a more effective inducer of apoptosis than bortezomib in lymphocytes from patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:1836–43. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]