Abstract

Meiotic recombination is a fundamental process in all eukaryotes. Among organisms where recombination initiates prior to synapsis, recombination preferentially occurs in short 1–2 kb regions, known as recombination hotspots. Among mammals, genotyping sperm DNA has provided a means of monitoring recombination events at specific hotspots in male meiosis. To complement these current techniques, we developed an assay for amplifying all copies of a hotspot from the DNA of male and female germ cells, cloning the products into E. coli, and SNP genotyping the resulting colonies using fluorescent technology. This approach directly examines the molecular details of crossover and non-crossover events of individual meioses at active hotspots while retaining the simplicity of using pooled DNA. Using this technique, we analyzed recombination events at the Mm1α hotspot located on mouse chromosome 1, finding that the results agree well with a prior genetic characterization of 3,026 male and 3,002 female meioses.

Introduction

The location and intensity of meiotic recombination events provide the substrate for evolutionary selection and underlie linkage gene mapping and population genetics. Recombination begins during meiosis I with a double strand break (DSB) that is eventually repaired to produce either a crossover, with the exchange of flanking parental DNA sequences across the site of DSB, or a non-crossover, in which the localized region surrounding the DSB acquires the DNA sequence of its partner chromatid without an exchange of flanking parental sequences (for a review of recombination pathways see Neale & Keeney [1]). In organisms, such as yeast, higher plants and mammals, where meiotic recombination initiates prior to synapsis, both outcomes of recombination are concentrated at preferred 1–2 kb regions, known as recombination hotspots [2]. These hotspots account for the majority of the crossover events and are surrounded by long regions with diminished crossover activity. Although all recombination hotspots are similar in length, their recombining activity can differ appreciably between the sexes and vary by several orders of magnitude [3]. Presently, although the protein components of the recombination machinery have been extensively characterized in yeast [1], we know relatively little about the factors controlling DSB locations and their recombination frequencies, particularly in mammalian systems. For a review of mammalian meiotic recombination hotspots, see Arnheim et al.[4]; Accordingly, the ability to monitor mammalian crossover and non-crossover events at the molecular level is a matter of considerable importance.

Characterizing the behavior of individual hotspots by their genetic outcomes requires substantial numbers of progeny, something that has been difficult for our own species and is limited among experimental mammals by the costs of generating and typing large genetic crosses. To overcome this limitation, sperm genotyping has become the technique of choice as each individual sperm represents the haploid product of a single meiotic event.

Sperm genotyping assays rely on PCR amplification from either single sperm DNA or pooled sperm DNA. In the single sperm assay first developed by Li et al. [5], individual sperm are separated, lysed and subjected to an initial round of whole genome amplification followed by a round of allele specific amplification to enrich crossover molecules, which are then genotyped by gel electrophoresis. An adaptation by Cullen et al. [6] added one extra PCR amplification step with radioactive labeling to analyze recombination activity among ~21,000 individual sperm. In single sperm assays, recombination events over large distances (> 10 kb) can be examined, but studying non-crossover events is not feasible [7].

To overcome the need for examining large numbers of single sperm and allow for finer mapping of hotspots, pooled sperm DNA genotyping was developed [8]. In pooled sperm analysis, the number of sperm examined is adjusted such that on average each aliquot is likely to contain a single crossover molecule. Positive detection of recombinant molecules by PCR using allele specific oligonucleotides, followed by dot blot hybridization, provides a quantitative estimate of the recombination rate at a chosen hotspot, and the crossover molecules obtained can be sequenced to provide molecular details of the recombination process. This technique was used to characterize several human recombination hotspots including TAP2 [9], the MHC region [10] and the pseudoautosomal pairing region [11]. Carrington and Cullen [12] have provided a comprehensive review of sperm genotyping techniques.

Although pooled sperm samples overcome the need for single sperm preparations and have been widely applied with considerable success, they do entail some limitations. The multi-step DNA enrichment process requires allele specific probes and radioactive hybridization probes are typically required for genotyping [8]. Moreover, there are an appreciable number of aliquots containing multiple crossover molecules. When sperm pools contain an average of 0.3 crossover molecule each, as the procedure is commonly carried out, the Poisson distribution indicates that 74% of samples will not contain a crossover molecule, 22.2% of samples will contain one crossover molecule and 3.7% of the samples will contain 2 or more crossover molecules, resulting in a positive PCR amplification for 25.9% of the samples. However, 14.2% of these positive samples contain amplified products derived from multiple recombinant clones [8]. The genotyping and/or sequencing of these samples cannot definitively reveal the molecular details of the individual recombinants, and these samples must be recognized and removed from the analysis. Reducing the probability of amplifying multiple recombinants to less than 5% requires analyzing pooled sperm DNA samples with an average of only 0.1 recombinant molecules, increasing the amount of necessary work.

As the term “sperm genotyping” implies, both single and pooled sperm genotyping are limited to detecting male recombination events. It is now known that the location and frequency of recombination events is substantially influenced by sex at both the hotspot and regional levels [13; 14]. An adaptation of the pooled sperm genotyping approach for female oocytes has been described [15], however this technique results in a mixture of primordial germ cell and somatic cells and requires the determination of the germ cell proportion by immunofluorescence.

Pooled sperm genotyping can test for the presence of crossovers among upwards of 100,000 sperm at a time and can detect recombination activity at less than 0.01cM. However, an important experimental challenge is to understand hotspots of higher activity as they account for the majority of mammalian recombination. In a recent analysis of approximately 1,400 recombination events across a 24.7 Mb region of mouse chromosome 1, 15 hotspots accounted for almost 50% of all crossovers [16]. The recombination rate at each of these hotspots was greater than 0.4 cM and hotspots whose activity was below 0.1 cM accounted for only a small fraction of all recombination events. It is likely that the majority of recombination events in the mouse genome, and likely in the human genome, are concentrated in hotspots with high activity.

Here we present a simple assay for monitoring the molecular details of both crossover and non-crossover outcomes of individual meioses at these more active hotspots that is applicable to both male and female gametes. It is based on an E. coli cloning strategy that combines the specificity of PCR amplification, DNA cloning and single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping to examine gametic cells in mammalian species with a very low incidence of duplicate clones. In this way, it provides both the advantages of pooled DNA samples and the sensitivity of assaying the details from individual meioses. Additionally, this technique is readily adapted to high throughput analyses of crossover and non-crossover events in a mammalian genome.

The potential of this assay is illustrated by its application to a hotspot named Mm1α located on mouse chromosome 1, and comparing the results with those obtained characterizing this hotspot from a large-scale genetic crosses.

Results

Recovery of individual haplotypes from pooled DNA

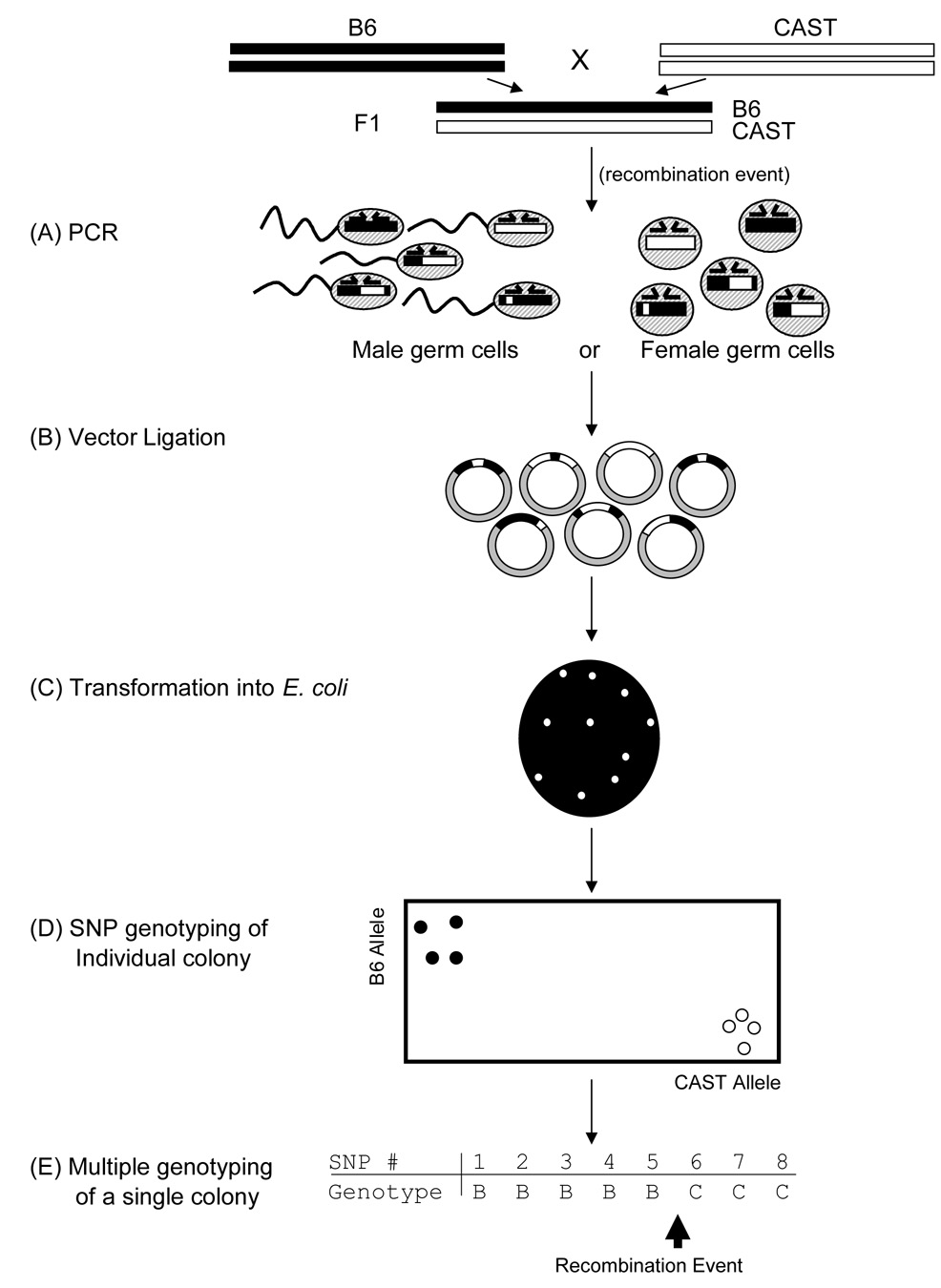

In our genotyping assay, DNA extracted from either male or female germ cells served as the starting material. Beginning with pooled DNA samples, both recombinant and non-recombinant copies of the targeted hotspot were PCR amplified using primers common to both parental haplotypes (Fig. 1A). To recover the products of meioses from the PCR reaction, the amplified fragments were cloned, ligated and transformed into E. coli such that each colony would represent a single DNA strand from the initial meiotic event (Fig. 1B and C). SNP genotyping was carried out directly on an aliquot of E. coli cultures grown from each colony in 96 well plates; prior plasmid purification proved unnecessary (Fig. 1D). The result is a simple PCR and cloning procedure that can be applied to either male or female germ cells.

Figure 1.

A diagram representation of the E. coli cloning assay for monitoring recombination events in gametic cells. (A) Common primers are designed in the region flanking the recombination hotspot of interest to amplify all recombinant and non-recombinant DNA from either male or female pooled DNA samples. (B) The subsequent pool of DNA is ligated into a vector and (C) individual clones recovered from E. coli. (D) The recovered clones are genotyped using fluorescence at polymorphic sites within the hotspot to reconstruct the recombination events. (E) Detection of recombination events from multiple SNP genotyping of a single E. coli colony.

Mm1α hotspot

As a proof-of-concept for the E. coli genotyping technique, the results of applying this assay to hotspot Mm1α were compared with the genetic data obtained from 3,026 male and 3,002 female meioses occurring in B6 × CAST F1 hybrids [16]. Hotspot Mm1α is located at 186.318 Mb (NCBI build 36) on chromosome 1. A 2.7 kb fragment was amplified, cloned and eight internal polymorphic sites were optimized for the Amplifluor genotyping system.

Control library and proper PCR amplification conditions

For all gametic assay procedures, PCR amplification is an essential step for obtaining sufficient DNA material for subsequent analysis. The importance of appropriate PCR conditions during this step cannot be over emphasized as improper PCR conditions can generate artifactual recombinant molecules, known as jump-PCR products, as a result of template switching during successive round of amplification [3; 17]. Using the generally accepted PCR condition of 1 minute per kilobase extension, “recombinant molecules” were detected in a 50:50 mixture of B6 and CAST sperm where they should not be present. The sequence of Mm1α hotspot contains a putative hairpin structure that may stall the Taq polymerase during elongation. The truncated product can then serve as the primer on a different allelic template in a subsequent round of amplification to generate artifactual recombinant molecules. To prevent template switching, we added DMSO to reduce the secondary structures in the DNA template, increased the elongation time to minimize the production of truncated molecules and shortened the annealing time to favor priming by added oligos. These steps prevented the generation of jump-PCR products. A control library prepared from a 50:50 mixture of B6 and CAST sperm provided equal frequencies of parental genotypes (221 B6 : 229 CAST), indicating unbiased amplification, and no crossover or non-crossover recombinants were detected in 450 clones. This validated the specificity of the PCR conditions for a recombination frequency of at least 0.2 cM. For hotspots with lower crossover activity, corresponding estimates of maximum detection sensitivity can be obtained by genotyping more control colonies.

Recombination activity of the Mm1α hotspot

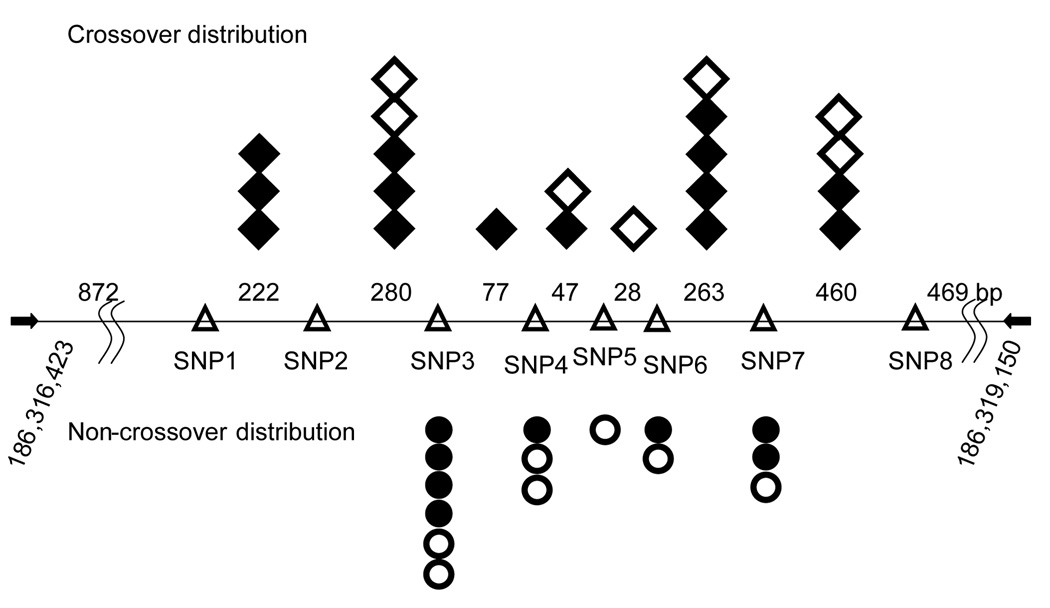

For the Mm1α hotspot, we analyzed a total of 500 clones obtained from sperm of F1 males and 830 clones from F1 female primordial follicles. In males, 14 crossovers and 8 non-crossovers were detected, while in females, 7 crossovers and 7 non-crossovers clones were obtained (Fig 2A). We further validated our technique by sequencing the plasmids from 10 crossover and 7 non-crossover colonies and verified their genotypes.

Figure 2.

The number of recombinant genotypes detected in the Mus musculus Mm1α hotspot in B6 × CAST F1 hybrids. The horizontal line indicates the amplified PCR fragment (flanking primer indicated as arrows). Triangles represent the location of the allelic SNPs between B6 and CAST, with the numbers between them denoting distances in base pairs. Recombinant molecules found in sperm are indicated in black and recombinant molecules from oocytes are in white. Diamonds represent crossover events while circles depict conversion events.

The frequencies and distribution of crossing over for both males and females were similar to that of our genetic cross[16], quantitatively validating the E. coli assay and confirming that the recombination activity at this hotspot is influenced by sex, with crossover activity appreciably higher in males than in females (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of the male and female crossover rates detected in the genetic cross and by the E. coli genotyping assay. The recombination frequency detected in our E. coli genotyping assay is similar to that obtained from the genetic cross with a higher crossover activity in males than females.

| Genetic Cross | E. coli genotyping Assay | |

|---|---|---|

| Males | 91 / 3,026 (3.0 ± 0.3%) | 14 / 500 (2.8 ± 0.7%) |

| Females | 16 / 3,002 (0.5 ± 0.1%) | 7 / 830 (0.8 ± 0.3%) |

Statistical analysis of unique recombinant molecules

Cloning from a large pooled sperm sample that has been amplified carries with it the possibility that multiple E. coli clones were derived from the same initial recombinant molecule. However, application of the Poisson distribution indicates that this is highly unlikely, which is illustrated by an analysis of the male data for Mm1α (14 crossovers in 500 clones). We began with 11,000 genomic haploid equivalents (2.7 pg per haploid mouse genome in 30 ng of pooled sperm DNA). Each haploid DNA originates from a single sperm cell and represents a unique meiotic event. PCR amplification of the sperm DNA is unbiased (as shown by our control DNA sample) and each haploid DNA is amplified by ~1×109 fold. The probability that the product of a given sperm is represented among the 500 selected clones is 500/11,000 = 0.045.

The probability that any two clones are a duplicates arising from the same initial meiotic event can be estimated using the Poisson distribution P(n) = (e−m mn) / n!, where n=2 and m is the likelihood that a given original sequence is represented in the aliquot (0.045). The probability of selecting two of the same molecules is then P(2) = (e−0.045 × 0.0452) / 2! or 0.00097. For males, we detected 14 crossovers in 500 clones, and for the likelihood that two of these are derived from the same meiosis is 1 – p(non-duplicates)13 or 1 – (1 – 0.00097)13 = 1.25%. That is, there is only a 1.25% probability that a set of 14 clones will contain a pair of clones duplicated from same initial molecule. This probability is further reduced by the fact that most recombinant molecules are readily distinguished by having distinct recombination sites. As such, recombinant molecules with different exchange points cannot be duplicate clones of each other. This further reduces the likelihood of analyzing two clones from the same initial molecule. For example, applying similar calculations to the 4 crossover clones with breakpoints between SNP6 and SNP7, the probability that two of these are duplicate clones is only 0.3%, and they cannot be duplicates of other recombinant clones. Thus, the probability of examining multiple representatives of the same initial recombinant molecule is minimal and can be further reduced by starting with a larger pool of sperm DNA.

Molecule details of crossover and non-crossover events

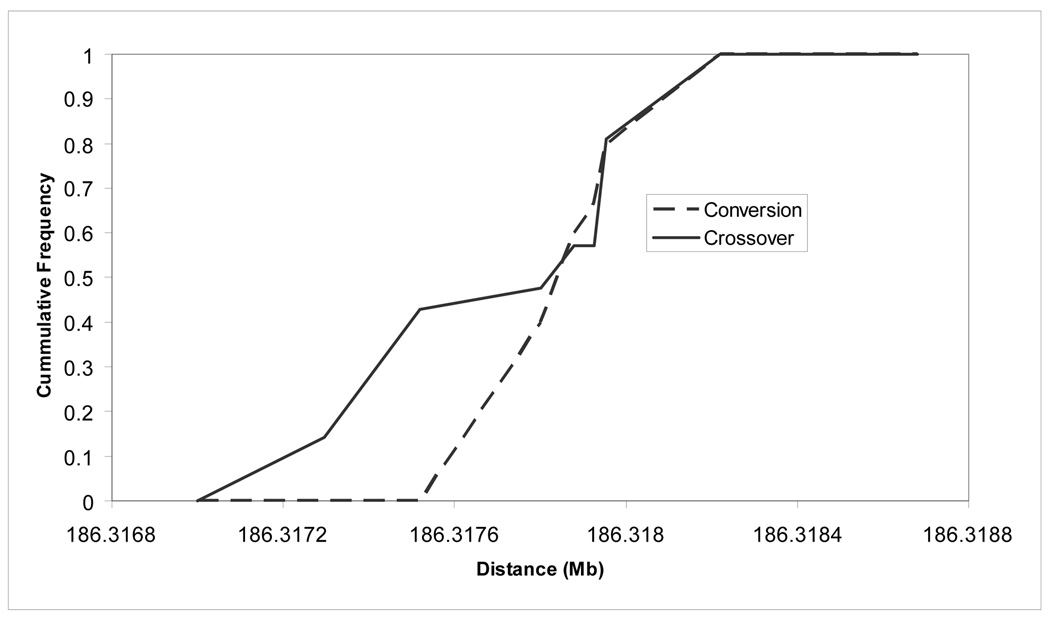

Examining the molecular details of the recombination products at the Mm1α loci, we found that males and females exhibited a similar distribution of crossover and non-crossover breakpoints (Fig 2A. The molecular details of each recombination event are in Supplementary Table 1). In both sexes, sites of non-crossover, detected by SNP marker conversions, were clustered closer than the sites of crossover exchange (Fig 3). This tighter distribution of non-crossover events is similar to those previously observed and conforms to the current recombination model where crossover and non-crossover recombination are processed by two different pathways [18].

Figure 3.

The cumulative frequencies of crossover and non-crossover breakpoints. The crossovers are spread across 923 bp while the conversion breakpoints are clustered within a 419 bp interval.

The length of a mammalian non-crossover conversion tract can vary from 70 bp to 300 bp [18]. For Mm1α no non-crossover conversions spanning two SNP markers were found; thus the longest conversion involving a single marker is the distance between its two flanking markers. On this basis, 75% of the non-crossover conversion tracts could have spanned 300 bp or longer, but some were definitely shorter. The three non-crossover recombinants at SNP4 must be less than 125 bp (spanning from SNP3 to SNP5) and the single non-crossover molecule at SNP5 is less than 77 bp (spanning from SNP4 to SNP6). In one recombinant molecule, both a conversion tract and crossover were detected from a single meiotic event (data not shown). This molecule is likely to be a crossover-associated conversion tract as a result of the mismatch repair following resolution of the Holliday junction. The true number of short non-crossover recombinants and conversions associated with a crossover is likely higher than what was observed as the detection of these short events is limited by the number and placement of informative markers between the parental strains.

Discussion

Sperm and oocytes contain haploid genomes derived from individual meiotic events. While sperm genotyping has been invaluable in monitoring male meiosis, adapting the technique to female meiosis has been less efficient, in part because of the difficulty of obtaining pure suspensions of primordial oocytes. We have devised a method to effectively analyze both male and female recombination events in a mammalian system by PCR amplification of the hotspot fragments from pooled DNA and recovering individual recombinant molecules by cloning. In the case of females, the starting material was pure female primordial follicles preparations obtained using the simple technique of Eppig et al. [19]. We can now use pooled DNA from either male or female germ cells to directly map individual recombination events.

The cloning approach outlined here considerably facilitates the identification and characterization of non-crossover recombinants as both cross-over and non-crossover molecules are amplified, cloned and SNP genotyped. In part, the power of the new approach also lies in the ease of genotyping it provides. Hotspot sequences from the initial sperm DNA are amplified and separated in high concentration as a result of the cloning step. SNP discrimination is robust and simplified, as each colony carries only one parental or recombinant allele, with no heterozygosity, and the cloned hotspot sequence is at >1,000 times its concentration compared to bulk mammalian genomic DNA. SNPs located in repetitive elements that were difficult to analyze in genomic DNA were easily typed using E. coli colony DNA. The fluorescent SNP genotyping system is an additional improvement over traditional sperm genotyping by avoiding radioactive labeling and gel electrophoresis.

The cloning assay also considerably reduces the complication of amplifying and genotyping multiple recombinant molecules in the same DNA sample. Each E. coli clone corresponds to a single meiotic product and complex recombinant clones are easily genotyped. The possibility of assaying duplicate recombinants is very small and can be reduced even further using a larger pool of DNA in the initial sample. In the initial PCR amplification, the use of common primers is non-discriminatory capturing all recombinant (crossover and non-crossover molecules) as well as non-recombinant genotypes within the targeted region. However, if desired, crossover recombinant molecules can be selectively amplified by using allele-specific primers (e.g. a B6 specific primer together with a CAST specific primer) for PCR amplification. Cloning of this DNA fraction would be considerably enriched for fragments representing crossover meiotic events in the targeted hotspot. In addition, this technique can be easily automated using a colony picker and a liquid dispenser to scale the E. coli colony picking and genotyping into a high throughput process for analyzing very large numbers of recombinant molecules, even at low frequency recombination hotspots.

In summary, our technique extends and complements the current pooled sperm genotyping procedures for investigating the molecule details of highly active mammalian recombination hotspots. Using this new approach, we have successfully mapped and characterized both male and female recombination events at the mouse Mm1α recombination hotspot. Although developed for mammals, the new technique should be applicable to a variety of organisms.

Materials and Methods

Germ cell isolation

Live sperm were recovered from dissected vas deferens of 20 week old males of the C57BL6/J (B6) and CAST/EiJ (CAST) mouse strains (The Jackson Laboratory, Maine, USA) and their F1 hybrids. Dissected vas deferens were placed in PBS and sperm were extracted by squeezing the tissue. Incubation at 37°C for ten minutes allows any remaining live sperm to swim out of the vas deferens. Sperm samples were centrifuged at 9,000 × g for 5 minutes and re-suspended in 100 µl of PBS with bovine serum albumin (BSA) (9.9mg/ml).

Female primordial follicles were purified from ovaries of B6 × CAST F1 animals using the method of Eppig et al. [19]. Briefly, four to six ovaries were dissected from 2–3 day old female pups and placed in PBS with BSA (1mg / ml). The ovarian bursa was disrupted with a 30 gauge needle and a single-cell suspension was obtained with agitation of the ovaries incubated at 37°C in 3.0 ml of digestion buffer (PBS with BSA, 0.05% trypsin, 0.53 mM EDTA and 0.02% DNase). Female germ cells were isolated by overnight incubation at 37°C, under these conditions somatic cells adhere to the culture dish while female germ cells remain unattached. To increase their purity, a second around of overnight incubation is done followed by isolation of free floating germ cells (~99% purity; personal communication; Eppig, J).

DNA extraction

DNA was extracted similarly from male sperm and female germ cells using the DNeasy DNA extraction kit (QIAgen, Valencia, CA. Supplementary Protocol-DY03). The cells were incubated overnight at 55°C in lysis Buffer X2 (20 mM TrisCl - pH 8.0, 20 mM EDTA, 200 mM NaCl, 80 mM DTT, 4% SDS and 250 µg/ml Proteinase K). After purification through the spin column, DNA was eluted using 100 µl of Buffer AE. An additional ethanol precipitation step was added to improve the quality of the final DNA sample.

PCR amplification, cloning and transformation

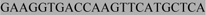

The targeted hotspot sequence was amplified using flanking primers common to both parental haplotypes (Table 1). PCR was performed on a Tetrad PCR system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) using approximately 30ng of DNA as template, 1X PCR buffer [60 mM Tris-SO4 pH8.9, 18 mM (NH4)2SO4, 2 mM MgSO4, 0.8 µM of each primers, 0.2 mM each dNTP, 5% DMSO] and 0.5 U Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase High Fidelity (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Cycling conditions consisted of an initial denaturing at 95°C for 2 minutes, followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 1 minute, 54°C for 15 seconds and 72°C for 8 minutes. In common with previous reports [3; 17], we found it important to employ conditions that mitigate against “jump-PCR” products created when incomplete amplicons serve as primers in subsequent rounds of amplification and create artifactual crossovers. Optimization was achieved by incorporating dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) into the PCR system to reduce DNA secondary structure, increasing the extension time to assure full length amplicons, and reducing the annealing time to enhance the preference for oligo primers over any incomplete fragments that might escape. The amplified products were ligated into a PCR2.1 vector using the TOPO T/A cloning kit and transformed into the TOP10 E. coli strain using the standard protocol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Transformed cells were grown overnight on LB agar plates with 40 µg/ml ampicillin and 20 µl of X-gal (40 mg/ml) spread on the surface.

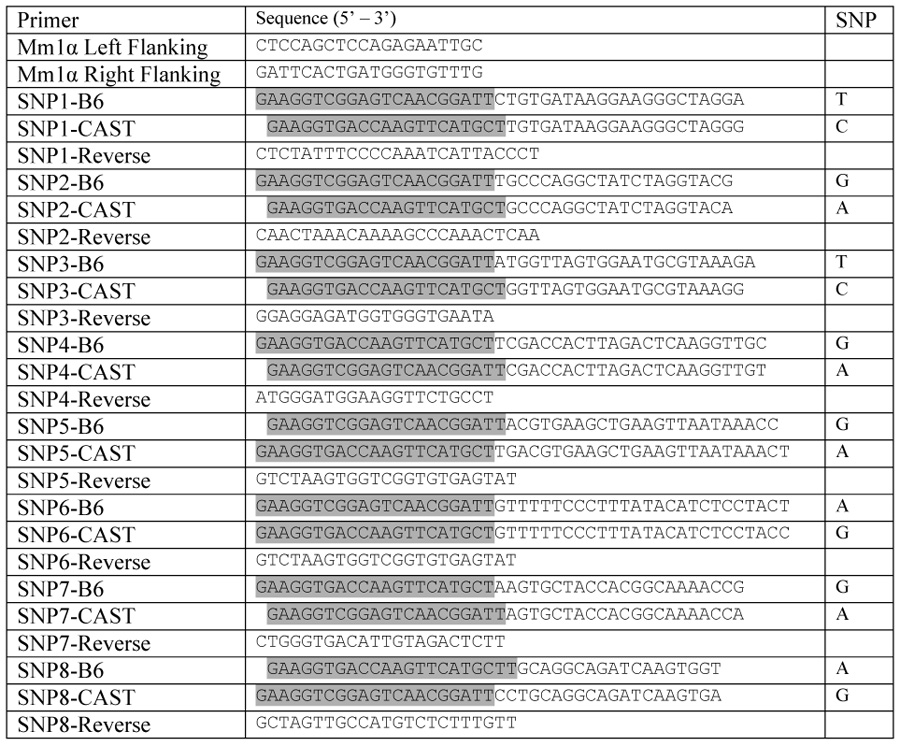

Table 1.

Primers used for PCR amplifying and SNP genotyping the Mm1α recombination hotspot on mouse chromosome 1. Allele specific primers are linked with either  or

or  as adaptor sequences for the Amplifluor SNP genotyping system.

as adaptor sequences for the Amplifluor SNP genotyping system.

|

E. coli culture and preparation

Individual, positive E. coli colonies from blue/white screening were grown in 80 µl of LB media using 96-well plates incubated at 37°C without shaking for 18 hours. Cell cultures were spun down while still in their plates at 3,450 × g for 10 minutes and resuspended in 80 µl of water.

SNP genotyping

SNPs were genotyped using the Chemicon Amplifluor SNPs HT FAM-JOE system (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and the alleles were discriminated on an ABI 7900HT Real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Framingham, MA) by end-point reading. Reactions were carried out in 384-well plates using 5 µl reaction volume consisting of a 2 µl sample of re-suspended E. coli culture without plasmid purification, plus 0.5 µl of 10x Reaction Mix S Plus, 0.4 µl 2.5 mM each dNTP, 0.25 µl 20X FAM Primer, 0.25 µl 20X JOE Primer, 0.25 µl SNP specific primer mix (0.5 µM green tailed allele-specific primer, 0.5 µM red tailed complementary allele-specific primer, 7.5 µM common reverse primer) and 0.05 µl Titanium Taq DNA polymerase (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) (For SNP primer sequences see Table 1). SNP genotyping was performed using the recommended protocol with an annealing temperature of 57°C in the initial 20 cycles.

SNP primer design

SNP primers were designed using the Amplifluor AssayArchitect software (https://apps.serologicals.com/AAA/).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Anita Hawkins for managing our mouse colonies and isolating sperm DNA, and Karen Wigglesworth and John Eppig for their help in female germ cell extraction.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Neale MJ, Keeney S. Clarifying the mechanics of DNA strand exchange in meiotic recombination. Nature. 2006;442:153–158. doi: 10.1038/nature04885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lichten M, Goldman AS. Meiotic recombination hotspots. Annu Rev Genet. 1995;29:423–444. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.29.120195.002231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeffreys AJ, Holloway JK, Kauppi L, May CA, Neumann R, Slingsby MT, Webb AJ. Meiotic recombination hot spots and human DNA diversity. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004;359:141–152. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2003.1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnheim N, Calabrese P, Tiemann-Boege I. Mammalian meiotic recombination hot spots. Annu Rev Genet. 2007;41:369–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li HH, Gyllensten UB, Cui XF, Saiki RK, Erlich HA, Arnheim N. Amplification and analysis of DNA sequences in single human sperm and diploid cells. Nature. 1988;335:414–417. doi: 10.1038/335414a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cullen M, Perfetto SP, Klitz W, Nelson G, Carrington M. High-resolution patterns of meiotic recombination across the human major histocompatibility complex. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:759–776. doi: 10.1086/342973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arnheim N, Calabrese P, Nordborg M. Hot and cold spots of recombination in the human genome: the reason we should find them and how this can be achieved. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:5–16. doi: 10.1086/376419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeffreys AJ, Murray J, Neumann R. High-resolution mapping of crossovers in human sperm defines a minisatellite-associated recombination hotspot. Mol Cell. 1998;2:267–273. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80138-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeffreys AJ, Ritchie A, Neumann R. High resolution analysis of haplotype diversity and meiotic crossover in the human TAP2 recombination hotspot. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:725–733. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.5.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeffreys AJ, Kauppi L, Neumann R. Intensely punctate meiotic recombination in the class II region of the major histocompatibility complex. Nat Genet. 2001;29:217–222. doi: 10.1038/ng1001-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.May CA, Shone AC, Kalaydjieva L, Sajantila A, Jeffreys AJ. Crossover clustering and rapid decay of linkage disequilibrium in the Xp/Yp pseudoautosomal gene SHOX. Nat Genet. 2002;31:272–275. doi: 10.1038/ng918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carrington M, Cullen M. Justified chauvinism: advances in defining meiotic recombination through sperm typing. Trends Genet. 2004;20:196–205. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Broman KW, Murray JC, Sheffield VC, White RL, Weber JL. Comprehensive human genetic maps: individual and sex-specific variation in recombination. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:861–869. doi: 10.1086/302011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lynn A, Schrump S, Cherry J, Hassold T, Hunt P. Sex, not genotype, determines recombination levels in mice. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:670–675. doi: 10.1086/491718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baudat F, de Massy B. Cis- and trans-acting elements regulate the mouse Psmb9 meiotic recombination hotspot. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paigen K, Szatkiewicz JP, Sawyer K, Leahy N, Parvanov ED, Ng SHS, Graber JH, Broman KW, Petkov PM. The Recombinational Anatomy of a Mouse Chromosome. PLoS Genet. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000119. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meyerhans A, Vartanian JP, Wain-Hobson S. DNA recombination during PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:1687–1691. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.7.1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jeffreys AJ, May CA. Intense and highly localized gene conversion activity in human meiotic crossover hot spots. Nat Genet. 2004;36:151–156. doi: 10.1038/ng1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eppig JJ, Wigglesworth K, Hirao Y. Metaphase I arrest and spontaneous parthenogenetic activation of strain LTXBO oocytes: chimeric reaggregated ovaries establish primary lesion in oocytes. Dev Biol. 2000;224:60–68. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.