Abstract

Objective

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) is greatly increased in women infected with sexually transmitted Human Papillomaviruses (HPVs) and who are co-infected with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection. Factors associated with promotion of HPV to CIN in these women include degree of immunosuppression and preventable behavioral factors such as tobacco smoking and psychological stress. Interventions such as cognitive behavioral stress management (CBSM) decrease stress and modulate disease activity in HIV-infected men though effects have not been established in HIV-infected women. This study examined the effects of CBSM on life stress and CIN in HIV+ minority women.

Methods

Participants were 39 HIV+ African American, Caribbean and Hispanic women with a recent history of an abnormal Papanicolaou smear. Participants underwent colposcopic examination, psychosocial interview, and peripheral venous blood draw at study entry and 9 months after being randomly assigned to either a 10-week CBSM group intervention (n = 21) or a one-day CBSM workshop (n = 18).

Results

Women assigned to the 10-week CBSM intervention reported decreased perceived life stress and had significantly lower odds of CIN over a 9-month follow-up, independent of CIN at study entry, HPV type, CD4+CD3+ cell count, HIV viral load, and tobacco smoking. Women free of CIN at follow-up reported decreases in perceived stress over time while those with CIN reported increases in perceived stress over the same period.

Conclusion

Although preliminary these findings suggest that stress management decreases perceived life stress and may decrease the odds of CIN in women with HIV and HPV.

Keywords: HIV, HPV, Cervical cancer, Stress, Stress Management

Introduction

Cervical cancer is a major public health problem among minority women in the U.S. and women in developing countries (1). Cervical cancer is one of the few cancers that is clearly promoted via behavioral pathways, specifically through the sexual transmission of Human Papillomaviruses (HPVs) (2), one of the most common sexually transmitted diseases worldwide (3). The new Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved HPV vaccine, Gardasil, has shown success in reducing the incidence of HPV infection and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN)—the early neoplastic changes that often precede invasive cervical cancer—among HPV uninfected women at risk for HPV. However, it is not indicated for the prevention of cervical cancer among women who are already HPV-infected (4). Thus, CIN and cervical cancer remain a public health threat among women with HPV infection, particularly those who also have anti-viral immune deficiencies induced by disease (immunodeficiency diseases) (5) or medical interventions (anti-rejection regimens following organ transplant) (6).

Factors associated with promotion of HPV to CIN in vulnerable populations include degree of immunosuppression (7), health behaviors such as tobacco smoking (8), and possibly psychological stress (negative life events) (9). Mechanisms explaining the association between psychological stress, neuro-immune regulation and the control of HPV-induced carcinogenic changes have been proposed to occur through neuroendocrine changes (10). Thus, women who are at especially heightened risk for HPV-associated CIN may include those co-infected with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), who are known to have compromised anti-viral immunity (11), a high prevalence of tobacco smoking (12), and elevated life stress (9).

If stress predicts greater risk of developing CIN in HIV+HPV+ co-infected women, then stress reduction interventions such as cognitive behavioral stress management (CBSM) (13) may decrease both stress and risk of CIN in this population. CBSM interventions, composed of relaxation training, cognitive behavior therapy, and interpersonal skills training, have been shown to decrease stress, alter immune parameters, and decrease HIV viral load in HIV+ men, and these effects appear to parallel alterations in negative mood and adrenal “stress” hormone regulation (13) (14). Less is known about the effects of CBSM intervention in HIV+ women, although there is evidence that it improves emotional quality of life from a study of mostly minority women with AIDS (15).

The present study tested the effects of CBSM intervention on stress and CIN in a sample of HIV+ low-income minority women with a recent history of abnormal Papanicolaou smears. We hypothesized that women assigned to a 10-week group CBSM intervention would report lower perceived stress over recent negative events and have lower odds of CIN in the 6-months following completion of the intervention. This intervention was evaluated in the context of biological (HIV viral load, immune status, HPV type, antiviral therapy), and behavioral (tobacco smoking) factors that could offer competing explanations for stress management effects.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited by doctoral and post-doctoral associates in clinical and health psychology from a specialty obstetrics-gynecology clinic providing obstetric, gynecologic, and primary care health services to HIV+ women at a large Southeastern medical complex. Inclusion criteria were: (a) HIV+ women ages 18 to 60 years old, (b) at least 2 Papanicolaou smears indicating low grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL) or at least 2 cervical biopsies indicating CIN I (mild or grade I neoplasia) in the 2 years prior to study entry, and (c) fluency in spoken English. Exclusion criteria were: (a) 2 or more negative Papanicolaou smears in the 2 years prior to study entry, (b) any history of high grade SIL (HSIL) or any history of CIN II, CIN III, or invasive cervical cancer, (c) any treatment procedures for CIN in the 6 months prior to study entry, (d) life expectancy < 12 months as determined by the study’s research nurse, and (e) current major, severe psychiatric illnesses (e.g., suicidality, psychoticism, HIV dementia) that would interfere with the ability to provide valid psychosocial assessment data and participate in the intervention. All participants read and signed an Institutional Review Board-approved informed consent form prior to the initiation of study procedures.

Given that HIV+ women constitute a traditionally hard-to-access population for research, special efforts were made to retain participants into the trial post-recruitment. Participants were compensated financially for completing study-related assessments, as well as for transportation, childcare, and meals associated with study visits. In between study-related visits, participants were called on a monthly basis to verify their contact information and remind them of their next study visit. Immediately prior to a study-related visit, they were contacted by phone, mail, or in-person to discuss and problem-solve any resource issues (lack of transportation, lack of reliable or safe childcare) or competing demands (recently employed) that could interfere with the ability to attend their assessment.

Colposcopic Examination

At study entry and 9-month follow-up, participants underwent a colposcopic examination by an advanced registered nurse practitioner with specialized colposcopy training from the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP). Colposcopic examinations were conducted according to ASCCP clinical practice guidelines and were comprised of a Papanicolaou smear, colposcopic-guided cervical biopsy, and cervical swab for the detection and subtyping of HPV infection (HPV detection and subtyping occurred at study entry only). Based on cervical biopsy results, participants were classified as being positive or negative for CIN at study entry and 9-month follow-up1. Hybrid Capture (HC) II assay (Digene Corporation, Gaithersburg, MD) was used to assess for the presence of high- and intermediate-risk (HR) HPV (“oncogenic”) subtypes and low-risk (LR) HPV subtypes at study entry.

Life Stress

Participants underwent a 60–90 minute psychosocial interview with female doctoral and post-doctoral associates in clinical health psychology at study entry and 9-month follow-up. This interview assessed overall psychiatric and psychological well-being, including assessment of life stress and health behaviors. Participants underwent 9-month follow-up assessments with a study staff member that did not serve as a group or workshop facilitator in order to reduce the potential for participants to respond to demand characteristics.

Life stress was measured using a 10-item abbreviated form of the Life Experiences Survey (16) previously adapted for use in a mostly minority, low income sample as described in other work (17). Briefly, the LES-10 assessed the prevalence of 10 major stressful life events that tend to occur with frequency among HIV+ women presenting for obstetric and gynecologic care. Participants first indicated whether any of the LES-10 events occurred in the 6 months prior to (a) study entry and (b) 9-month follow-up. For each event endorsed, participants then rated the degree to which they found that event stressful using the following scale: “0” = not at all stressful, “1” = mildly stressful, “2” = moderately stressful, and “3” = extremely stressful. The stress impact ratings were then summed to provide a total life stress score at study entry and 9-month follow-up.

Immune and Viral Status

At study entry and 9-month follow-up, peripheral blood was collected in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) tubes (Vacutainer-EDTA, Becton-Dickinson, Rutherford, NJ). CD4+CD3+ T lymphocyte counts were determined from whole blood with a Coulter XL flow cytometer using four-color direct immunofluorescence. Change in CD4+CD3+ cell count over the follow-up period was calculated by subtracting CD4+CD3+ cell counts at study entry from cell counts at 9-month follow-up. Plasma HIV viral load at study entry was determined using an ultrasensitive in vitro reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction assay (AMPLICOR, Roche Laboratories, US #83088) with a lower limit of 50 viral copies/mL. Individuals with an undetectable HIV viral load were imputed into our statistical database as having a viral load of 50 copies/mL.

Control Variables

Pack-years of smoking was assessed as a biobehavioral control variable given its association with cervical carcinogenesis (18). Alcohol use was also assessed as a potential control variable, given that heavy alcohol use is associated with suppressed cellular immunity (19). Self-reported use of illicit substances was very low in this sample; therefore, frequency of use of illicit substances was not examined as a control variable. In addition, frequency of unsafe sexual behaviors was assessed, as they may confer risk for sexually transmitted infection/reinfection, immunosuppression, and cervical cancer. Self-reported use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) was also assessed as a potential control variable, as some research suggests that HAART use increases the odds of regression of HPV-associated neoplasia in HIV+ women (20).

Randomization Procedures

Participants were randomly assigned to either the 10-week CBSM group intervention or a one-day CBSM group workshop by study staff following completion of study entry assessment procedures. Participants and assessors were blinded to experimental condition during completion of all study entry procedures. Once a block of approximately 9 participants had completed study entry colposcopic examination procedures, they were randomly assigned to either the 10-week CBSM group intervention or the one-day CBSM workshop at a 2:1 ratio (experimental:control). This ratio allowed for randomization of approximately 6 participants to the 10-week group, a group size that we have found necessary to convene a group.

10-Week CBSM Intervention

The 10-week CBSM group intervention was derived from a validated program initially used in men with HIV infection (for review see [(13)]) and adapted for women with HIV through the use of focus groups and other accepted tailoring procedures (21). The program consisted of 10-weekly, 135 minute sessions delivered to groups of approximately 4–6 women by two trained facilitators according to a detailed training manual (22). Facilitators included doctoral trainees, post-doctoral fellows, and licensed psychologists with faculty appointments in clinical health psychology. All sessions were audiotaped and reviewed in weekly clinical supervision by a licensed psychologist.

Each 135-minute session was comprised of 45 minutes of relaxation training (RT) and 90 minutes of cognitive behavioral (CB) training. During the RT component, participants were instructed in diaphragmatic breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, imagery, autogenic techniques, and meditation and were then guided through a relaxation induction using one of these techniques. The 90-minute CB-training component focused on increasing awareness of the effects of stress, identifying and reframing automatic thoughts, improving productive coping skills, and improving interpersonal effectiveness through anger management, assertiveness training, productive use of one’s social network, and safer sex negotiation. Special attention was paid to psychological, behavioral, social, and physical challenges frequently encountered by HIV+ women with HPV and/or CIN (21).2 Participants were assigned weekly homework, including stress monitoring and relaxation practice, in order to facilitate learning and generalization of skills to real-world settings.

One-Day CBSM Workshop

Participants randomly assigned to the one-day CBSM workshop attended a 5-hour, abbreviated version of the 10-week CBSM group intervention. The workshop was scheduled to occur on a day during week 6 of the 10-wk CBSM condition’s sessions to correspond to the midpoint of the period of that intervention. The workshop was facilitated by the same persons running the 10-week groups and was supervised by a licensed psychologist. It was comprised of four 20-minute relaxation modules/inductions, four 40-minute CBSM modules, and two 30-minute breaks. Although the workshop was offered in a group setting, where group process, group member participation, and peer-to-peer transmission and sharing of information were occurring, the dose of this intervention was less than the 10-wk condition, no homework was assigned and home-based practice of skills were not included.

Aims and Statistical Analyses

Our specific aims were 2-fold: to examine whether a 10-week CBSM group intervention (a) reduced the odds of CIN at 9 month follow-up, and (b) reduced life stress among HIV+ women at risk for cervical cancer. We hypothesized that participants undergoing the 10-week CBSM intervention would have significantly lower odds of CIN at 9-month follow-up than those in the one-day CBSM workshop. Binary logistic regression controlling for established co-factors in cervical carcinogenesis was used to test this hypothesis. Allocation to the 10-week group (yes [1] or no [0]) was used as the predictor and presence of CIN at 9-month follow-up (yes [1] or no [0]) was used as the criterion while controlling for the presence of CIN at study entry. Participants undergoing the 10-week CBSM group intervention were hypothesized to report greater reductions in life stress across the 9-month follow-up period compared to those in the one-day CBSM workshop. Here we computed group (10-week CBSM group, one-day CBSM workshop) × time (baseline, 9-month follow-up) effects on life stress ratings using Repeated Measures Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). These analyses, although restricted to cases with complete data, were run independent of whether or not participants attended any of their intervention sessions3.

Results

Participant Characteristics

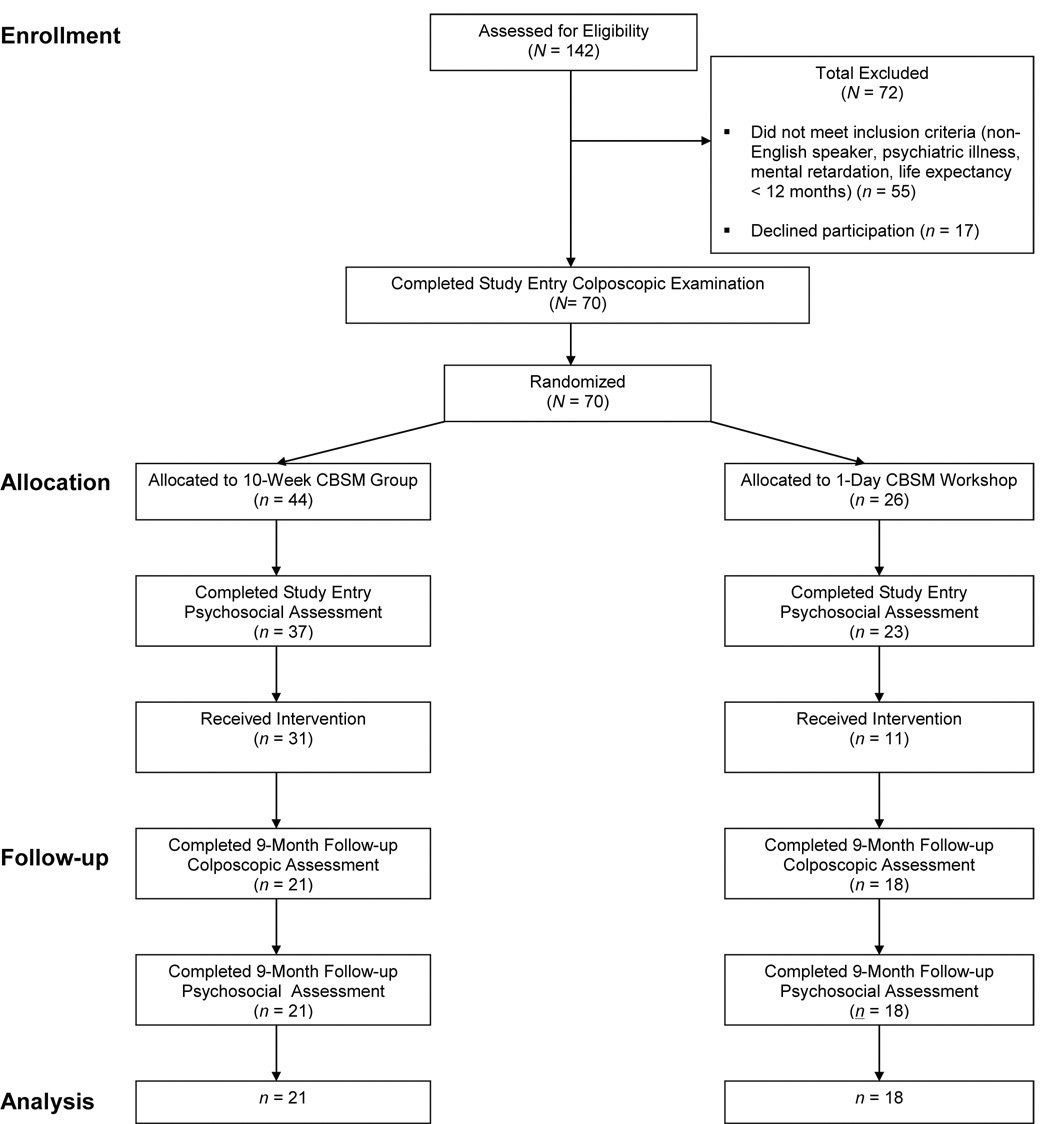

Participants were recruited between 2000 and 2004. We screened 142 women for this trial, of whom 72 were excluded due to failure to meet entry criteria or unwillingness to participate. The remaining 70 women completed a study entry colposcopic examination; 44 participants were randomized to the 10-week CBSM group, while 26 were randomized to the one-day CBSM workshop. There were no differences between participants assigned to the 10-week CBSM group and those assigned to the one-day CBSM workshop on any variables examined, including demographics (age, race/ethnicity, marital status, religion, gravida, number of living children, education, income), health behaviors (pack-years of smoking, alcohol use, HAART medication usage, use of depression or anxiety medication), health status (HIV viral load, CD4+CD3+ cell number, HIV disease stage, lowest CD4+CD3+ cell count ever, presence of cervical CIN at study entry, presence of HR-HPV at study entry), or psychological status (life stress at study entry) (all ps > .10).

Of the 44 women assigned to the 10-week CBSM group, 37 (84%) completed a study entry psychosocial assessment; of the 26 one-day CBSM workshop participants, 23 (88%) completed this assessment. There was no significant difference between the experimental conditions in the proportion of participants who completed a psychosocial assessment at study entry, χ2 = .26, p = .62. Among the 10-week CBSM group participants 21/44 (47%) completed a colposcopic examination and psychosocial interview at 9-month follow-up compared to 18/26 (69%) of one-day CBSM workshop participants, χ2 = 3.06, p = .08. Reasons for study attrition following completion of study procedures were not qualitatively different between experimental conditions and included inability of research staff to contact participants to schedule an assessment (participant change in residence, disconnection of telephone service, change of telephone number to unlisted number) and participant withdrawal due to competing demands (recently employed, lack of adequate childcare, “too busy”).

Regardless, we examined whether there were any demographic, health behavior, health status, or psychological status differences among participants who completed 9-month follow-up procedures and those who did not by experimental condition. There were no differences among the groups on any variables examined (c.f. paragraph above for full list of variables examined) (all ps > .10).

The final sample of 39 participants had a mean age of 31.23 years (SD = 8.56), a mean yearly income of $11,852 (SD = $8,750), and a mean education of 11.79 years (SD = 1.14 years). Fifty-one percent (20/39) of participants reported being single/never married, 20% (8/39) were married or in a committed relationship, 10% (4/39) separated, 13% (5/39) divorced, and 5% (2/39) widowed. Twenty percent (8/39) of participants were born outside of the United States, with the majority of these from the Bahamas and Haiti. Ninety percent (35/39) of the sample was Black, and the majority of these participants identified themselves as African-American or Caribbean-American ethnicity. Five percent (2/39) of the sample identified themselves as Hispanic.

HIV-Related Health and Behavior Characteristics

The mean CD4+CD3+ cell count was 414 cells/mm3 (SD = 279 cells/mm3) (n = 38) at study entry and 471 cells/mm3 (SD = 298 cells/mm3) (n = 32) at 9-month follow-up. Among participants who had complete immune data at both study entry and 9-month follow-up (n = 31), there was no significant change in CD4+CD3+ cell count from study entry to 9-month follow-up, t (30) = −0.38, p = .71. In addition, there were no significant effects of the 10-week CBSM intervention on CD4+CD3+ cells/mm3 over this period F (1, 29) = .71, p = .41.

At baseline, 36% (14/39) of participants were asymptomatic for HIV infection, 26% (10/39) were symptomatic, and 39% (15/39) had received a clinical AIDS diagnosis. Fifty percent (18/36) had a history of a CD4+CD3+ cell count < 200 cells/mm3. The mean HIV viral load (log 10 transformed) at study entry was 3.08 copies/mL (SD = 1.28 copies/mL) (n = 38), and 32% (12/38) of the sample had undetectable viral load (≤50 copies/mL). There were no effects of the CBSM intervention on HIV viral load across the follow-up period, F (1, 29) = .003, p = .96.

Seventy-seven percent (30/36) of participants reported taking HAART medications at study entry, and 76% (22/29) of individuals on HAART with complete self-reported adherence data reported 100% adherence to their regimen in the 4 days prior to study entry.4

CIN and HPV Prevalence

Eighty-five percent (33/39) of participants had evidence of CIN by cervical biopsy or SIL by cervical cytology at study entry, 84% (31/37) were positive for HPV DNA at study entry, and 77% (30/37) were positive for oncogenic or high risk (HR) HPV subtypes, specifically, at study entry. There were no significant differences in the prevalence of CIN or HR-HPV infection at study entry between the experimental and control participants. (Table 1).

Table 1.

Prevalence of CIN and HR-HPV infection by experimental condition.

| Experimental condition | χ2 | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10-week CBSM group (n = 21) |

one-day CBSM workshop (n = 18) |

|||

| Presence of CIN at study entry | ||||

| Yes | 18 | 15 | .04 | .84 |

| No | 3 | 3 | ||

| Presence of HR-HPV infection at study entry | ||||

| Yes | 16 | 14 | .25 | .62 |

| No | 3 | 4 | ||

Note. HR-HPV = High-Risk Human Papillomavirus. CBSM = cognitive behavioral stress management.

Relations Among Potential Biobehavioral Control Variables and CIN

As demonstrated in Table 2, women with CIN at study entry did not have significantly greater HIV viral load (log10 transformed) at study entry. However, participants with CIN at 9 month follow-up had marginally greater HIV viral load (log10 transformed) at study entry (M = 3.35 copies/mL, SD = 1.35 copies/mL) than those without neoplasia at follow-up (M = 2.51 copies/mL, SD = .89 copies/mL), F (1, 36) = 3.81, p = 0.06. As expected, presence of CIN at study entry was significantly associated with HR-HPV infection, χ2 (1) = 4.51, p = .04 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Relations between potential biobehavioral control variables and CIN at study entry and 9 month follow-up.

| Presence of CIN | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study entry | 9 month follow-up | |||||

| Yes | No | Test Statistic (Fa or χ2 b) |

Yes | No | Test Statistic (Fa or χ2 b) |

|

| HIV viral load (log10 transformed) at study entry (copies/mL) | ||||||

| M | 3.20 | 2.27 | 2.43 a | 3.35 | 2.51 | 3.81 a * |

| SD | 1.30 | .82 | 1.35 | .89 | ||

| CD4+CD3+ cell count at study entry (cells/mm3) | ||||||

| M | 413.55 | 414.40 | .000a | 384.54 | 476.75 | .89a |

| SD | 292.98 | 184.80 | 297.16 | 232.73 | ||

| HAART use at study entry | ||||||

| No. Yes | 25 | 5 | .000b | 20 | 10 | .00b |

| No. No | 5 | 1 | 4 | 2 | ||

| Frequency of vaginal sex without condom use in month prior to study entry | ||||||

| M | 1.24 | .17 | 1.19 a | 1.08 | 1.08 | .00 a |

| SD | 2.39 | .41 | 2.24 | 2.29 | ||

| No. of drinks of alcohol in week prior to study entry | ||||||

| M | .61 | .17 | .58 a | .73 | .15 | 1.76 a |

| SD | 1.39 | .41 | 1.54 | .38 | ||

| Pack years of cigarette smoking | ||||||

| M | 1,091.23 | 337.50 | 1.05 a | 837.76 | 1,230.81 | .48 a |

| SD | 1,751.87 | 817.92 | 1,616.75 | 1,763.08 | ||

| HR-HPV infection at study entry | ||||||

| No. Yes | 27 | 3 | 4.51 b ** | 21 | 9 | 1.84 b |

| No. No | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | ||

Note. HR-HPV = High-Risk Human Papillomavirus. HAART = Highly active antiretroviral therapy. CBSM = cognitive behavioral stress management.

p ≤ .10

p ≤.05.

Intervention Effects on CIN at 9-Month Follow-Up

At 9-month follow-up, 67% (26/39) of the sample had evidence of CIN by cervical biopsy or SIL by cervical cytology. Despite equivalent levels at study entry by group, a significantly greater proportion of individuals assigned to the one-day CBSM seminar evidenced CIN or SIL at follow-up (15/18) compared to those assigned to the 10-week CBSM (11/21), χ2(1) = 4.18, p = .04. Hierarchical binary logistic regression analysis was used to predict CIN at 9-month follow-up period from experimental condition. As a conservative measure, we controlled for the major, well-documented biobehavioral risk factors for cervical carcinogenesis, including declines in CD4+CD3+ cell count over follow-up, presence of HR-HPV types at study entry, HIV viral load at study entry, and pack-years of cigarette smoking at study entry. We controlled for HIV viral load but not for self-reported HAART use, because self-reported HAART adherence was highly correlated with HIV viral load, and HIV viral load is a better indicator of the efficacy of HAART usage than self-reported use alone. After controlling for these risk factors and CIN at study entry, women in the 10-week CBSM group had significantly lower odds of CIN at 9-month follow-up compared to those in the one-day CBSM workshop, OR = .05, 95% Confidence Interval (CI) = .003 – .70, p = .03. The entire equation accounted for a significant amount of variance in CIN at 9 month follow-up, χ2 (6)= 14.52, p = .03 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Odds of presence of CIN at 9-month follow-up for HIV+ women assigned to the 10-week cognitive behavioral stress management (CBSM) group.

| Wald Statistic |

Odds Ratio |

95% Confidence Interval for Odds Ratio |

p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Step 1. Biobehavioral variables | ||||||

| Presence of CIN at study entry | .87 | 4.33 | .20 | 93.96 | .35 | |

| Presence of HR-HPV types at study entry | .45 | 2.14 | .23 | 19.96 | .51 | |

| Change in CD4+CD3+ cell count (cells/mm3) from study entry to 9-month follow-up | 1.81 | 1.00 | .99 | 1.00 | .18 | |

| Pack years of cigarette smoking at study entry | .05 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | .83 | |

| HIV viral load (copies/mL) at study entry (log10 transformed) | .32 | 1.27 | .56 | 2.86 | .58 | |

| Step 2. Experimental condition | ||||||

| Assignment to 10-week CBSM group | 4.94 | .05 | .003 | .70 | .03 | |

Note. HR-HPV = High-Risk Human Papillomavirus. Significance of overall model, χ2 (6) = 14.52, p = .03.

Intervention Effects on Life Stress

At study entry, 38% (15/39) of the sample received a life stress score of “0,” indicating that no life events in the past 6 months were reported as being experienced as negative. Thirty-one percent (12/39) received a life stress score of “1,” indicating that one major life event was experienced as mildly negative. Thirty-one percent (12/39) received a life stress score greater than or equal to “2,” indicating that either (a) multiple life events were rated as mildly negative, or (b) at least one event was rated as moderately or severely negative. Table 4 lists the most frequently endorsed life events (including ones rated as negative) in the 6 months prior to study entry.

Table 4.

Prevalence of negative life events in 6 months prior to study entry.

| Life Event | No. (%) of Ss Reporting Life Event Occurred |

No. (%) of Ss Reporting Life Event Occurred and was “Negative” |

|---|---|---|

| Death of a close family member or friend | 16 (41%) | 12 (31%) |

| Major change in sleeping habits | 14 (36%) | 12 (31%) |

| Major change in eating habits | 9 (23%) | 4 (10%) |

| Gained a new family member | 12 (31%) | 0 (0%) |

| Changed a work situation | 9 (23%) | 3 (8%) |

| Changed residence | 12 (31%) | 2 (5%) |

Note. Life stress measured by an abbreviated 10-item version of the Life Experiences Survey (LES-10) (16).

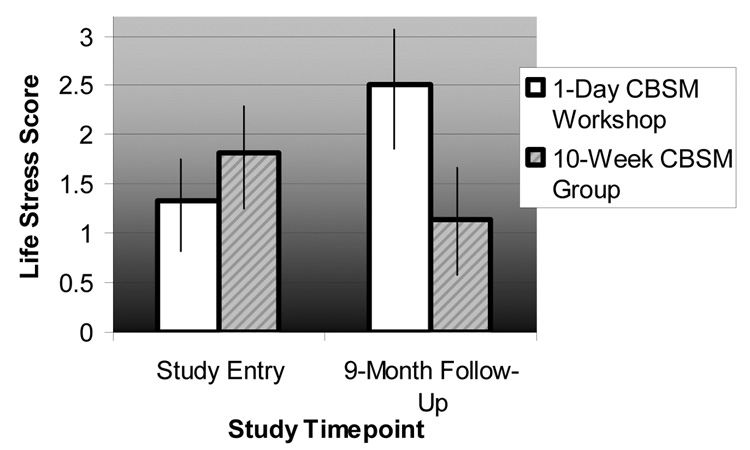

Repeated Measures ANOVA revealed that the 10-week CBSM intervention significantly buffered increases in life stress across the 9-month follow-up period, F (1, 37) = 5.13, p = .03.5 While average life stress scores nearly doubled among women in the one-day CBSM workshop (M study entry = 1.33, SD study entry = 1.85; M 9-months = 2.50, SD 9-months = 3.24), life stress scores decreased by approximately 37% among women in the 10-week CBSM group (M study entry = 1.80, SD study entry = 2.52; M 9-months = 1.14, SD 9-months = 1.56) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Life stress ratings in HIV+ women assigned to either a 10-week cognitive-behavioral stress management (CBSM) group intervention or a 1-day CBSM workshop across a 9-month follow-up period.

Note. Experimental condition × timepoint interaction significant, F (1,37) = 5.13, p = .03. Life stress measured using an abbreviated 10-item version of the Life Experiences Survey (LES-10) (16).

Associations Among Life Stress Change And CIN Across The Study Period

We have previously shown in a separate sample that greater life stress was associated with greater odds of progression and/or persistence of CIN in women co-infected with HPV and HIV (9). Given that the 10-week CBSM intervention had effects on both CIN and life stress in the present study, we examined whether reductions in life stress mediated the effects of the CBSM intervention on CIN at 9 month follow-up. We followed the method outlined by Preacher and Hayes (23), which uses the Sobel test to determine whether the effects of the predictor on the criterion are significantly attenuated by the inclusion of the mediator into the model. This analysis failed to support a mediation effect. As an exploratory analysis we also examined whether increases in life stress from baseline to 9 month follow-up related to presence of CIN at 9 month follow-up, irrespective of group assignment. A univariate analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed with change in life stress from study entry to 9 month follow-up as the dependent variable and presence of CIN at 9-month follow-up as the independent variable. The model was adjusted for the presence of CIN at study entry, HIV viral load at study entry, change in CD4+CD3+ cell count from study entry to 9 month follow-up, pack-years of cigarette smoking, and presence of HR-HPV at study entry. Increase in life stress from study entry to 9 month follow-up was associated with a greater likelihood of presence of CIN at 9 month followup, F (1, 24) = 4.88, p = .037. Women with presence of CIN at 9 month follow-up had a mean increase in life stress of 1.00 (SD = 2.47), while those free of CIN at 9-month follow-up had a mean decrease in life stress of 0.54 (SD = 2.07) over the follow-up period.

Discussion

Cervical cancer remains a major health problem globally, especially among individuals in developing countries faced with abject poverty and numerous barriers to accessing adequate health care. Immunosuppressed women, such as those with HIV, who also have co-morbid HR-HPV infection, are particularly at risk for developing cervical neoplastic disease (5). Although the newly FDA-approved HPV vaccine has shown success in decreasing the incidence of HPV infection in naïve hosts (4), it is not indicated for preventing cervical cancer among women with HPV infection. Even if HPV vaccines are shown to reduce the incidence of CIN and cancer among HPV-infected women, it remains to be seen whether they will also be successful among HPV+ women with compromised cellular immune repertoires due to co-infection with HIV.

Factors associated with promotion of HPV to CIN in HIV-infected populations likely include degree of immunosuppression (7), as well as behavioral factors such as tobacco smoking (8), and psychological stress (negative life events) (9). Down-regulation of immune parameters has been found in healthy medical students undergoing examination stress (24), individuals with depression (25), elderly caregivers with high stress (26), and men with HIV/AIDS with high stress (27). Elevated stress also predicts faster progression to AIDS in HIV+ men, though clear pathophysiological pathways for specific opportunistic infections and neoplasms remain unclear. Since the odds of an HPV-infected woman developing CIN increase if she is co-infected with HIV (28), then it is plausible that stress-related decrements in anti-viral immune functioning may compound this risk (10).

The present study tested the effects of a psychosocial intervention on stress and health outcomes in this population based on the following rationale—if stress predicts greater odds of CIN in HIV+HPV+ co-infected women, then stress reduction interventions such as cognitive behavioral stress management (CBSM) (13) may decrease both stress and the odds of CIN in this population. We found that HIV+ women (the vast majority of whom were co-infected with HR-HPV subtypes) who were assigned to a 10-week group-based CBSM intervention reported decreased perceived life stress and revealed lower odds of CIN at 9-month follow-up. Women with CIN at 9-month follow-up reported significant increases in life stress across the follow-up period, while those without CIN at follow-up reported decreases in life stress across the follow-up period. Given that the assessment of life stress at follow-up occurred prior to the disclosure of cervical biopsy results at follow-up, the relationship between high life stress and CIN cannot be attributed to their learning of their CIN status. CBSM intervention effects on stress and CIN appeared to be independent of CIN at study entry, HPV type, CD4+CD3+ cell count, HIV viral load, and tobacco smoking.

Although intervention effects were observed on both life stress and CIN, CBSM-associated reductions in life stress did not emerge as a significant mediator of the relationship between the CBSM intervention and CIN at follow-up. While it is possible that we may have lacked sufficient power to detect a significant effect, future research should also examine other potential psychosocial mediators of this relationship, such as negative mood, as well as potential moderators, such as coping and social support. It was interesting that women who were free of cervical CIN at follow-up had mean decreases in life stress over time whereas those showing persisting cervical CIN at follow-up reported increases in perceived life stress over a similar period. While it is unclear whether life stress changes were attributable to the CBSM intervention, perceived changes in cervical CIN status, or due to external factors it is noteworthy that this association between life stress and cervical CIN mirrors similar findings in independent samples of HIV+HPV+ women reported elsewhere (9) and is the first demonstration of a prospective association between changes in life stress ad changes in CIN in this population.

The form of CBSM intervention tested in this study, composed of relaxation training, cognitive behavior therapy and interpersonal skills training, delivered in ten 2-hour group sessions, has previously been shown to decrease stress, impact immunologic indicators of herpesvirus activity, and decrease HIV viral load in HIV+ men, effects that appeared due to improved relaxation skills, increased social support, decreased negative mood and improved adrenal hormone regulation (using indices of urinary cortisol and norepinephrine) (13) (14) (29). Less is known about the biobehavioral effects of CBSM intervention in HIV+ women. This is the first study demonstrating that CBSM may provide psychological and health benefits for women with HIV who are at heightened risk for CIN.

Although this trial demonstrated significant effects on stress and CIN after controlling for possible biobehavioral confounding variables, caution is in order when interpreting these findings due to a small sample size and the greater attrition rate in the 10-week CBSM condition. It is noteworthy but not unexpected that attrition occurred in spite of the special efforts made to retain participants. Many of our participants were exposed to abject poverty, unsafe living conditions/homelessness, interpersonal violence, and other severe life circumstances. Our retention efforts were probably effective at easing barriers to research participation for some women exposed to these severe life circumstances. It is therefore worth noting that, women who were able to overcome barriers to research participation may have had healthier coping strategies at study entry. If so, our ability to generalize our results to women with severely impaired coping/psychopathology may be limited.

We considered the possibility that the greater attrition from the CBSM group may have biased the results in favor of the CBSM condition, such that only the healthiest participants remained available for the follow-up measurements. However, the only significant difference that we detected between experimental participants who contributed data at follow-up and those who withdrew or were lost to follow-up was that a significantly greater proportion of those contributing data at follow-up reported using HAART medications at study entry. Although the reason for this difference is unclear, it is possible that those who withdrew or were lost to follow-up were more ill due to not using HAART, or were simply less adherent to any prescribed interventions, including both physician-prescribed HAART regimens and study-related procedures. If so, it is possible that our results cannot be generalized to women who are not on or adhering to a HAART regimen. Given that nonadherence is a common phenomenon among individuals in the HIV community, the public health implications of our results are presently unclear and are worthy of future research. There remains the possibility that the women available for analysis at follow-up in the CBSM condition were more healthy or motivated than those who were lost to follow-up thus biasing the CBSM group to have better cervical CIN outcomes than controls in study analyses. Attrition is always a threat to validity in hard-to-reach populations and its impact can be significant in studies with moderate sample sizes.

An additional limitation of this study is our lack of an untreated control group. Control participants were offered a one-day stress management seminar as a minimal treatment condition for ethical purposes, as cognitive-behavioral techniques are empirically supported for the treatment of depression and anxiety. However, as a result, we are unable to determine whether the 10-week intervention improved participants’ health and well-being or whether the one-day seminar somehow introduced a risk factor for compromised health and well-being. Future research should seek to use ethical study designs that allow for this question to be answered.

In light of these limitations, larger scale studies are necessary to ensure our confidence in the reliability of these preliminary findings and to seek to understand the possible public health implications of this research. Larger scale studies should seek to understand who benefits the most from the intervention, which intervention components are most strongly associated with health benefits, and how these intervention components can be disseminated to HIV+ HPV+ women by community agencies. Larger scale studies will also provide sufficient power to use more sophisticated statistical analyses that allow the inclusion of participants with some missing data at follow-up, such as linear mixed effects modeling.

Putative associations between psychological stress, neuro-immune regulation and HPV-induced carcinogenic changes may underlie the effects of CBSM shown here (10). Stress-induced activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis results in elevated glucocorticoids (GCS), such as cortisol (30), which has been shown to contribute to an inverted Th1/Th 2 cytokine ratio, possibly down-regulating anti-viral immune activity (10) and favoring unchecked HPV-induced neoplastic changes. Glucocorticoids also contribute to the expression of some oncogenic herpesviruses (31) (32) and may have similar effects on HPV gene expression (33) mediated through interactions with cellular proto-oncogenes such as ras (34) and/or via evading cellular immune responses by down-regulating tumor Class I MHC molecules (35). Since CBSM has been shown to decrease cortisol levels in HIV+ persons (36), it is plausible that the present effects on stress and CIN were mediated, in part, by alterations in cortisol levels.

Other stress-related neuroendocrine substances such as norepinephrine (NE), known to be modulated by CBSM among HIV+ persons in other work (45) have been shown to contribute to enhanced expression of HIV and resistance to HAART medication (37) (38) and can accelerate HIV-1 replication by enhancing cellular susceptibility to infection (39), activating viral gene transcription (37), and suppressing anti-viral cytokines (38). Thus, the present findings may also be explained by reductions in NE during stress management training. However, these putative mechanisms remain speculative until directly assessed in clinical studies.

The present study provides preliminary evidence that participating in a CBSM intervention is associated with reduced life stress and decreased odds of CIN among HIV+ women, most of whom were also HR-HPV+ and therefore at high risk for CIN progression. Prior prospective studies related psychosocial factors to CIN in women co-infected with HIV and HPV (9). The present findings appear to mirror these and suggest further that decreases in life stress may also predict decreased likelihood of CIN over time in this population. More generally, this suggests that psychosocial factors like life stress may confer their greatest influence on disease risk in populations where risk is identifiable and high. These findings may also be relevant to the growing number of healthy women with HPV infection, currently the number one sexually transmitted infection in the U.S. (40). Within this population there is good evidence for health disparities with risk of HPV infection being significantly elevated in non-Hispanics, African Americans, and those below the poverty level (40). Future work should include larger scale trials to evaluate the effects of CBSM intervention on both stress and quality of life, as well as cellular immune status, cervical neoplastic disease progression and other disease outcomes in the growing populations of HPV-infected as well as HIV+HPV+ co-infected women, who are at heightened risk for both overwhelming stress and compromised future health.

Figure 1. Participant flow diagram for the present randomized clinical trial.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

In cases where a cervical biopsy was not able to be completed (N =15 at study entry and 12 at 9-month follow-up), evidence of squamous intraepithelial lesions (SIL) by cervical cytology was used to code the cervical CIN outcome.

For example, the module on increasing stress awareness focused on how stress affects one’s ability to adhere to Papanicolaou smears screening and HIV medications, as adherence to these regimens may reduce risk for promotion of HPV to cervical cancer.

Thus, all participants with complete data at study entry and 9-month follow-up, regardless of their adherence to study interventions, were included in analyses.

Among individuals who endorsed using HAART medications at study entry, HIV viral load at study entry was significantly negatively correlated with self-reported adherence (r = −0.43, p = 0.03) (n = 48).

These findings persisted when intervention effects on life stress were examined for all participants who contributed life stress data at study entry and 9-month follow-up regardless of completeness of colposcopic examination data, F (1,47) = 4.82, p = 0.04, n = 49.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2006. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Munoz N, Bosch FX, de Sanjose S, Herrero R, Castellsague X, Shah KV, Snijders PJ, Meijer CJ. Epidemiologic Classification of Human Papillomavirus Types Associated With Cervical Cancer. N.Engl.J.Med. 2003 Feb 6;348(6):518–527. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bosch FX, de Sanjose S. Chapter 1: Human Papillomavirus and Cervical Cancer--Burden and Assessment of Causality. J.Natl.Cancer Inst.Monogr. 2003;31:3–13. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a003479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmiedeskamp MR, Kockler DR. Human Papillomavirus Vaccines. Ann.Pharmacother. 2006;40(7):1344–1352. doi: 10.1345/aph.1G723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palefsky JM, Holly EA. Chapter 6: Immunosuppression and Co-Infection With HIV. J.Natl.Cancer Inst.Monogr. 2003;(31):41–46. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a003481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Penn I. Post-Transplant Malignancy: the Role of Immunosuppression. Drug Saf. 2000;23(2):101–113. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200023020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Man S. Human Cellular Immune Responses Against Human Papillomaviruses in CIN. Expert.Rev.Mol.Med. 1998:1–19. doi: 10.1017/S1462399498000210. 7-3-1998: 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carcinoma of the Cervix and Tobacco Smoking: Collaborative Reanalysis of Individual Data on 13,541 Women With Carcinoma of the Cervix and 23,017 Women Without Carcinoma of the Cervix From 23 Epidemiological Studies. Int.J.Cancer. 2006 Feb 15;118(6):1481–1495. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pereira DB, Antoni MH, Danielson A, Simon T, Efantis-Potter J, Carver CS, Duran RE, Ironson G, Klimas N, O'Sullivan MJ. Life Stress and Cervical Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions in Women With Human Papillomavirus and Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Psychosom.Med. 2003;65(3):427–434. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000041620.37866.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Antoni MH, Lutgendorf SK, Cole SW, Dhabhar FS, Sephton SE, McDonald PG, Stefanek M, Sood AK. The Influence of Bio-Behavioural Factors on Tumour Biology: Pathways and Mechanisms. Nat.Rev.Cancer. 2006;6(3):240–248. doi: 10.1038/nrc1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pantaleo G, Cohen OJ, Schacker T, Vaccarezza M, Graziosi C, Rizzardi GP, Kahn J, Fox CH, Schnittman SM, Schwartz DH, Corey L, Fauci AS. Evolutionary Pattern of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Replication and Distribution in Lymph Nodes Following Primary Infection: Implications for Antiviral Therapy. Nat.Med. 1998;4(3):341–345. doi: 10.1038/nm0398-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feldman JG, Minkoff H, Schneider MF, Gange SJ, Cohen M, Watts DH, Gandhi M, Mocharnuk RS, Anastos K. Association of Cigarette Smoking With HIV Prognosis Among Women in the HAART Era: A Report From the Women's Interagency HIV Study. Am.J.Public Health. 2006;96(6):1060–1065. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.062745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Antoni MH. Stress Management and Psychoneuroimmunology in HIV Infection. CNS.Spectr. 2003;8(1):40–51. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900023440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Antoni MH, Carrico AW, Duran RE, Spitzer S, Penedo F, Ironson G, Fletcher MA, Klimas N, Schneiderman N. Randomized Clinical Trial of Cognitive Behavioral Stress Management on Human Immunodeficiency Virus Viral Load in Gay Men Treated With Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy. Psychosom.Med. 2006;68(1):143–151. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000195749.60049.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lechner SC, Antoni MH, Lydston D, LaPerriere A, Ishii M, Devieux J, Stanley H, Ironson G, Schneiderman N, Brondolo E, Tobin JN, Weiss S. Cognitive-Behavioral Interventions Improve Quality of Life in Women With AIDS. J.Psychosom.Res. 2003;54(3):253–261. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarason IG, Johnson JH, Siegel JM. Assessing the Impact of Life Changes: Development of the Life Experiences Survey. J.Consult Clin.Psychol. 1978;46(5):932–946. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.46.5.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pereira DB, Antoni MH, Danielson A, Simon T, Efantis-Potter J, Carver CS, Duran RE, Ironson G, Klimas N, O'Sullivan MJ. Life Stress and Cervical Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions in Women With Human Papillomavirus and Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Psychosom.Med. 2003;65(3):427–434. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000041620.37866.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carcinoma of the Cervix and Tobacco Smoking: Collaborative Reanalysis of Individual Data on 13,541 Women With Carcinoma of the Cervix and 23,017 Women Without Carcinoma of the Cervix From 23 Epidemiological Studies. Int.J.Cancer. 2006 Mar 15;118(6):1481–1495. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cook RT. Alcohol Abuse, Alcoholism, and Damage to the Immune System--a Review. Alcohol Clin.Exp.Res. 1998;22(9):1927–1942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minkoff H, Ahdieh L, Massad LS, Anastos K, Watts DH, Melnick S, Muderspach L, Burk R, Palefsky J. The Effect of Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy on Cervical Cytologic Changes Associated With Oncogenic HPV Among HIV-Infected Women. Aids. 2001 Nov 9;15(16):2157–2164. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200111090-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pereira DB, Chesney M, Antoni MH. Innovative approaches to health psychology: Prevention and treatment - Lessons learned from AIDS. Washington DC: American Psychological Association Press; 2002. Interventions for mothers during pregnancy and postpartum: Behavioral and pharmacological approaches. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Antoni MH, Pereira DB. Cognitive behavioral stress management for HIV+ women with Human Papillomavirus infection. Keeping hope alive. 1999 Ref Type: Unpublished Work. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS Procedures for Estimating Indirect Effects in Simple Mediation Models. Behav.Res.Methods Instrum.Comput. 2004;36(4):717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glaser R, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Malarkey WB, Sheridan JF. The Influence of Psychological Stress on the Immune Response to Vaccines. Ann.N.Y.Acad.Sci. 1998 May 1;840:649–655. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09603.x. 649-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Irwin M. Psychoneuroimmunology of Depression: Clinical Implications. Brain Behav.Immun. 2002;16(1):1–16. doi: 10.1006/brbi.2001.0654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R, Gravenstein S, Malarkey WB, Sheridan J. Chronic Stress Alters the Immune Response to Influenza Virus Vaccine in Older Adults. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 1996 Apr 2;93(7):3043–3047. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leserman J, Petitto JM, Golden RN, Gaynes BN, Gu H, Silva SG, Folds JD, Evans DL. Impact of Stressful Life Events, Depression, Social Support, Coping, and Cortisol on Progression to AIDS. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157(8):1221–1228. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.8.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maiman M, Fruchter RG, Sedlis A, Feldman J, Chen P, Burk RD, Minkoff H. Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Accuracy of Cytologic Screening for Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia in Women With the Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Gynecology and Obstetrics. 1998;68:233–239. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1998.4938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cruess S, Antoni M, Cruess D, Fletcher MA, Ironson G, Kumar M, Lutgendorf S, Hayes A, Klimas N, Schneiderman N. Reductions in Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2 Antibody Titers After Cognitive Behavioral Stress Management and Relationships With Neuroendocrine Function, Relaxation Skills, and Social Support in HIV-Positive Men. Psychosom.Med. 2000;62(6):828–837. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200011000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chrousos GP, Gold PW. The Concepts of Stress and Stress System Disorders. Overview of Physical and Behavioral Homeostasis. JAMA. 1992 Mar 4;267(9):1244–1252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cacioppo JT, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Malarkey WB, Laskowski BF, Rozlog LA, Poehlmann KM, Burleson MH, Glaser R. Autonomic and Glucocorticoid Associations With the Steady-State Expression of Latent Epstein-Barr Virus. Horm.Behav. 2002;42(1):32–41. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2002.1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glaser R, Kutz LA, MacCallum RC, Malarkey WB. Hormonal Modulation of Epstein-Barr Virus Replication. Neuroendocrinology. 1995;62(4):356–361. doi: 10.1159/000127025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bromberg-White JL, Meyers C. Comparison of the Basal and Glucocorticoid-Inducible Activities of the Upstream Regulatory Regions of HPV18 and HPV31 in Multiple Epithelial Cell Lines. Virology. 2003 Feb 15;306(2):197–202. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(02)00041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pater MM, Hughes GA, Hyslop DE, Nakshatri H, Pater A. Glucocorticoid-Dependent Oncogenic Transformation by Type 16 but Not Type 11 Human Papilloma Virus DNA. Nature. 1988 Oct 27;335(6193):832–835. doi: 10.1038/335832a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bartholomew JS, Glenville S, Sarkar S, Burt DJ, Stanley MA, Ruiz-Cabello F, Chengang J, Garrido F, Stern PL. Integration of High-Risk Human Papillomavirus DNA Is Linked to the Down-Regulation of Class I Human Leukocyte Antigens by Steroid Hormones in Cervical Tumor Cells. Cancer Res. 1997 Mar 1;57(5):937–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Antoni MH, Cruess SE, Cruess DG, Kumar M, Lutgendorf S, Ironson G, Dettmer E, Williams J, Klimas N, Fletcher MA, Schneiderman N. Cognitive-Behavioral Stress Management Reduces Distress and 24-Hour Urinary Free Cortisol Output Among Symptomatic HIV-Infected Gay Men. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2000;22:29–37. doi: 10.1007/BF02895165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cole SW, Naliboff BD, Kemeny ME, Griswold MP, Fahey JL, Zack JA. Impaired Response to HAART in HIV-Infected Individuals With High Autonomic Nervous System Activity. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2001 Oct 23;98(22):12695–12700. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221134198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cole SW, Korin YD, Fahey JL, Zack JA. Norepinephrine Accelerates HIV Replication Via Protein Kinase A-Dependent Effects on Cytokine Production. J.Immunol. 1998 Jul 15;161(2):610–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cole SW, Jamieson BD, Zack JA. CAMP Up-Regulates Cell Surface Expression of Lymphocyte CXCR4: Implications for Chemotaxis and HIV-1 Infection. J.Immunol. 1999 Feb 1;162(3):1392–1400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dunne EF, Unger ER, Sternberg M, McQuillan G, Swan DC, Patel SS, Markowicz LE. Prevalence of HPV infection among females in the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;297:813–819. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.8.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]