Abstract

Among 235 extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae (ESBL) isolates collected from a nationwide surveillance performed in Taiwan, 102 (43.4%) were resistant to amikacin. Ninety-two of these 102 (90.2%) isolates were carrying CTX-M-type β-lactamases individually or concomitantly with SHV-type or CMY-2 β-lactamases. The armA and rmtB alleles were individually detected in 44 and 37 of these 92 isolates, respectively. One isolate contained both armA and rmtB. The coexistence of the aac(6′)-Il and rmtB genes was detected in three isolates. CTX-M-type β-lactamase genes belonging to either group 1 (CTX-M-3 and CTX-M-15) or group 9 (CTX-M-14) were found in all armA- or rmtB-bearing ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates, and all were conjugatively transferable. All except one of the isolates bearing armA produced CTX-M enzymes of group 1, and the remaining isolate bearing armA produced a group 9 CTX-M-type β-lactamase. On the contrary, in the majority of rmtB carriers, the CTX-M-type β-lactamase belonged to group 9 (62.2%). Molecular typing revealed that the amikacin-resistant ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates were epidemiologically unrelated, indicating that the acquisition of resistance was not through the spread of a resistant clone or a resistance plasmid. A tandem repeat or multiple copies of blaCTX-M-3 were found in some armA-bearing isolates. An ISEcp1 insert was found in all CTX-M ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates carrying armA or rmtB. In conclusion, the concomitant presence of a 16S rRNA methylase gene (armA or rmtB) and blaCTX-M among amikacin-resistant ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates is widespread in Taiwan.

Monotherapy with a broad-spectrum β-lactam such as cefotaxime or ceftriaxone is commonly used to treat gram-negative bacterial infections. The recent worldwide increase in the incidence of infections due to extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing organisms has resulted in a therapeutic dilemma, as the choice of antibiotics is limited because of ESBL production (19). The synergistic effects of β-lactams and aminoglycosides, two distinct classes of antibiotics, are mediated through the inhibition of the bacterial cell wall and protein synthesis, respectively. Combination therapy with β-lactams and aminoglycosides is well accepted for the treatment of bacteremia caused by ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates (20) as well as other systemic infections (15). Although resistance to either one of these classes is commonly seen, resistance to aminoglycosides and β-lactams is less commonly encountered (21). Thus, the use of a combination of a broad-spectrum cephalosporin and an aminoglycoside is one of the alternative choices for the treatment of systemic infections when susceptibility testing results are not immediately available.

Previous studies have confirmed that concomitant β-lactam and aminoglycoside resistance is of great concern. Usually, resistance to aminoglycosides is due to the presence of aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes (25), and the dissemination of the resistance might be mediated by integrons (11, 17), such as by an aac(6′)-I-like gene in a class 1 integron cassette. However, recent reports have highlighted the importance of the emergence of 16S rRNA methylase genes (the armA and rmtB genes) in conferring high-level resistance to all aminoglycosides (1, 9, 16, 29). In this study, we used a national collection of ESBL K. pneumoniae isolates in Taiwan to investigate the correlation between the type of ESBL and the mechanisms responsible for amikacin resistance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

During a nationwide study of antibiotic resistance in 2002, 235 ESBL-producing isolates of K. pneumoniae were collected from seven medical centers and 13 regional hospitals in Taiwan (seven hospitals from the north, six hospitals from the south, five hospitals from the west, and two hospitals from the east). Primary screening for ESBL production was done by the individual participating hospitals. Further confirmation of ESBL production was performed at the National Health Research Institutes by use of the criteria described below.

Susceptibility testing and confirmation of ESBL production.

Antimicrobial susceptibility was determined by the broth microdilution method (4), according to the guidelines of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) (5). The following antimicrobial agents were used: ampicillin, cefazolin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, cefoxitin, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, imipenem, amikacin, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. All drugs were incorporated into Mueller-Hinton broth (Trek Diagnostic System Ltd., West Sussex, United Kingdom) in serial twofold concentrations from 0.025 to 64 μg/ml. Two control strains, Escherichia coli ATCC 35218 and ATCC 25922, were included in each test run. Inoculated plates were incubated at 35°C for 16 to 18 h. The MIC of each antimicrobial agent was defined as the lowest concentration that inhibited visible growth of the organism.

ESBL producers were also reconfirmed by a disc diffusion method. The pairs of discs tested included cefotaxime-clavulanic acid (30/10 μg) and cefotaxime (30 μg) discs and ceftazidime-clavulanic acid (30/10 μg) and ceftazidime (30 μg) discs (Becton Dickinson). An increase in the zone diameter of ≥5 mm for the clavulanic acid-supplemented discs compared with the zone diameter for the plain discs was considered suggestive of ESBL production.

Detection of genes for 16S rRNA methylases, β-lactamases, class 1 integron structure, and promoter regions of blaCTX-M genes.

The armA, rmtB, blaSHV, blaCTX-M,blaTEM, and blaCMY genes and the gene for the class 1 integron structure were detected by PCR amplification. The oligonucleotide primers used for the detection of the three aminoglycoside resistance mechanisms, including two methylases (arm-like and rmt-like genes) and an aminoglycoside-modifying enzyme located in the integron, were used as described previously (13). The primers used for the detection of the genes described above are shown in Table 1. Bacterial DNA was prepared by suspending one loop of fresh colonies in 500 μl of sterile distilled water and heating the mixture at 95°C for 10 min. The reaction was carried out in a total volume of 50 μl. The amplification conditions were as follows: 95°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 54°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min. After 35 cycles of amplification, 72°C was applied for 10 min to terminate the primer extension. The linkage of blaCTX-M with the ISEcp1 and IS26 elements was determined with forward primers specific for the internal regions of ISEcp1 and IS26 and the CTX-M reverse primer (Table 1) to investigate whether the promoter regions for the blaCTX-M genes were present. The cycling conditions were 95°C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 25 s, 52°C for 40 s, and 72°C for 50 s, with a final extension at 72°C for 6 min.

TABLE 1.

Sequences of primers used for specific gene detection

| Target gene | Primer name | Primer sequence (5′-3′) | Positiona | GenBank accession no. or reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| blaSHV | SHV-F | GGG TTA TTC TTA TTT GTC GC | 132-151 | AF124984 |

| SHV-R | TTA GCG TTG CCA GTG CTC | 1059-1042 | ||

| blaTEM | TEM-F | ATA AAA TTC TTG AAG AC | 1551-1531 | X64502 |

| TEM-R | TTA CCA ATG CTT AAT CA | 472-493 | ||

| blaCTX-M G1 | CTX-1F | GGT TAA AAA ATC ACT GCG TC | 8 | |

| CTX-1R | TTG GTG ACG ATT TTA GCC GC | |||

| blaCTX-MG2 | CTX-2F | ATG ATG ACT CAG AGC ATT CG | 8 | |

| CTX-2R | TGG GTT ACG ATT TTC GCC GC | |||

| blaCTX-M G9 | CTX-9F | ATG GTG ACA AAG AGA GTG CA | 8 | |

| CTX-9R | CCC TTC GGC GAT GAT TCT C | |||

| blaCMY | CMY-F | GAC AGC CTC TTT CTC CAC A | 1908-1926 | AY581205 |

| CMY-R | TGG AAC GAA GGC TAC GTA | 2922-2905 | ||

| armA | armA-F | AGG TTGTTT CCA TTT CTG AG | 2054-2073 | AY220558 |

| armA-R | TCT CTT CCA TTC CCT TCT CC | 2644-2625 | ||

| rmtB | rmtB-F | CCC AAA CAG ACC GTA GAG GC | 1521-1540 | AB103506 |

| rmtB-R | CTC AAA CTC GGC GGG CAA GC | 2105-2086 | ||

| Class 1 integron | 5′CS | GGC ATC CAA GCA GCA AG | 1236-1252 | AF174129 |

| 3′CS | AAG CAG ACT TGA CCT GAT | 2813-2830 | ||

| ISEcp1 | ISEcp1 U1 | AAA AAT GAT TGA AAG GTC GT | 1545-1564 | AJ242809 |

| IS26 | IS26F | AGC GGT AAA TCG TGG AGT GA | 213-232 | X00011 |

| CTX-M reverse | MA3 | ACY TTA CTG GTR CTG CAC AT | 273-292 | X92506 |

The location of each primer can also be checked by use of the computer search program BLAST, provided at the website http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi.

The amplicons were sequenced, and the entire sequence of each gene was compared with the sequences in the GenBank nucleotide database at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/. Sequencing was done with corresponding primers specific for the blaSHV, blaCTX-M, blaTEM, blaCMY, armA, and rmtB genes by the method of Sanger et al. (24a). An automated sequencer (ABI Prism 377 sequencer; Perkin-Elmer) was used.

Conjugation experiments.

Rifampin (rifampicin)-resistant strain E. coli JP-995 or nalidixic acid-resistant strain E. coli λ1037 was used as the recipient (26). None of the donors could grow on MacConkey agar with either rifampin (100 μg/ml) or nalidixic acid (50 μg/ml). The recipients and the donors were separately inoculated into brain heart infusion broth (Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England) and were incubated at 37°C for 4 h. They were then mixed together at a ratio of 1:10 (by volume) and were incubated overnight at 37°C. A 0.1-ml volume of the overnight broth mixture was then spread onto a MacConkey agar plate containing rifampin (100 μg/ml) or nalidixic acid (50 μg/ml), as appropriate, and either cefotaxime (10 μg/ml) or ceftazidime (5 μg/ml). Lactose-fermenting transconjugants were then selected from the agar plate.

PFGE analysis.

Total DNA was prepared, and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was performed as described previously (6). The restriction enzyme XbaI (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) was used at the temperature suggested by the manufacturer. Restriction fragments were separated by PFGE in a 1% agarose gel (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) in 0.5× TBE buffer (45 mM Tris, 45 mM boric acid, 1.0 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) for 22 h at 200 V at a temperature of 14°C and with ramp times of 2 to 40 s by using a CHEF Mapper apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, CA). The gels were then stained with ethidium bromide and photographed under UV light. The resulting genomic DNA profiles, or fingerprints, were interpreted according to established guidelines (27).

Plasmid restriction enzyme digestion profile.

Plasmid DNA from the transconjugant was prepared by the alkaline extraction method (12). Analysis of the plasmids from the transconjugants restricted with EcoRI (Gibco BRL) was performed according to the supplier's instructions. Molecular weights were determined with a bacteriophage lambda DNA-EcoRI marker (Fermantas). armA-positive and rmtB-positive isolates were randomly selected from among the isolates of different PFGE types for further plasmid digestion.

Southern blot hybridization with probes specific for armA, rmtB, and blaCTX.

The isolates used for hybridization were randomly selected from among the isolates from different regions and hospitals that had different plasmid digestion profiles. The EcoRI-digested plasmids from armA and rmtB carriers were hybridized with probes specific for blaCTX, armA, and rmtB (24). Southern blot hybridization was performed with a digoxigenin labeling and detection kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany), as recommended by the manufacturer. The probes specific for armA, rmtB, and blaCTX-M were obtained by PCR amplification with the primer pairs listed in Table 1.

RESULTS

Susceptibility testing results.

The antimicrobial susceptibility testing results for the 235 ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae are shown in Table 2. All isolates were resistant to ampicillin and cefazolin, and ESBL production was confirmed by ESBL screening tests. Most of the isolates (94.9%) were intermediate or resistant to cefotaxime. The rates of resistance to the other antibiotics tested decreased in the following order: trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (91.5%), gentamicin (91.1%), ceftazidime (83.8%), ciprofloxacin (59.1%), cefoxitin (56.6%), and amikacin (54.9%). Only five (2.1%) isolates were found to be nonsusceptible to imipenem.

TABLE 2.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing results for 235 ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates

| Antibiotic | MIC (μg/ml)

|

No. (%) of isolates with the following result:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50% | 90% | Susceptible | Intermediate | Resistant | |

| Ampicillin | >64 | >64 | 0 | 0 | 235 (100) |

| Cefazolin | 32 | 32 | 0 | 0 | 235 (100) |

| Cefoxitin | 16 | 32 | 102 (43.4) | 38 (16.2) | 95 (40.4) |

| Cefotaxime | 64 | 64 | 12 (5.1) | 77 (32.8) | 146 (62.1) |

| Ceftazidime | 32 | 32 | 38 (16.2) | 39 (16.6) | 158 (67.2) |

| Imipenem | 0.25 | 2 | 230 (97.9) | 3 (1.3) | 2 (0.8) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 4 | 4 | 96 (40.9) | 15 (6.3) | 124 (52.8) |

| Gentamicin | 16 | 16 | 21 (8.9) | 9 (3.9) | 205 (87.2) |

| Amikacin | 32 | 64 | 106 (45.1) | 27 (11.5) | 102 (43.4) |

| SXTa | 4 | 4 | 20 (8.5) | 0 | 215 (91.5) |

SXT, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Detection of 16S rRNA methylase, β-lactamase, class 1 integron, ISEcp1, and IS26.

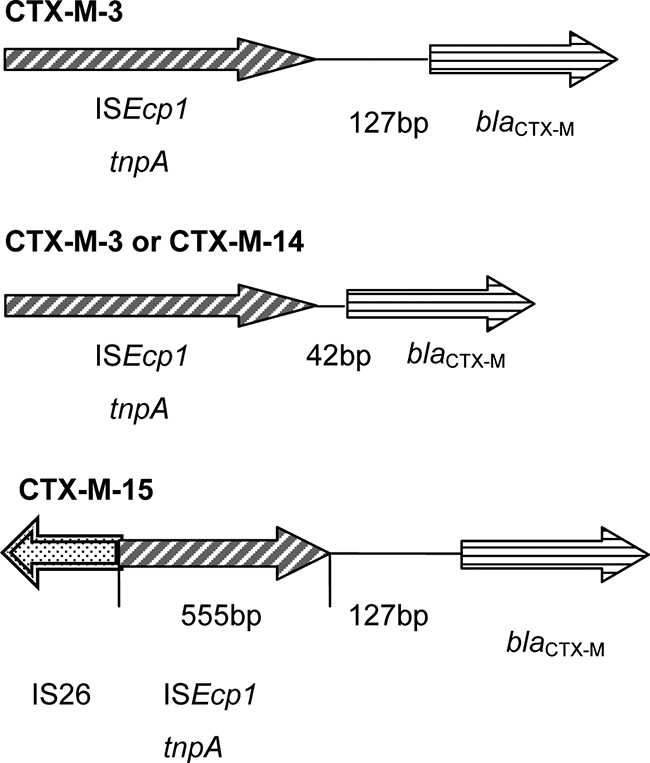

Among the 235 isolates, apart from the non-ESBLs SHV-1, SHV-11, LEN-1, TEM-1, and TEM-31, ESBL-encoding genes, including SHV-5, SHV-12, CMY-2, CTX-M-3, CTX-M-14, and CTX-M-15, were detected in all 102 amikacin-resistant (MICs > 32 μg/ml) ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates (Table 3). Among these 102 amikacin-resistant strains, the armA and rmtB genes were individually detected in a total of 44 and 37 isolates, respectively. The coexistence of armA and rmtB was detected in one isolate. Sixteen isolates carried neither the 16S rRNA methylase gene nor aac(6′)-Il. A class 1 integron was detected in 170 of 235 isolates (72.3%). Amikacin resistance due to aminoglycoside-modifying aac(6′)-Il, located within the conserved region of the class 1 integron gene cassette, was found in nine isolates. rmtB and aac(6′)-Il were concomitantly found in three isolates. Six amikacin-resistant isolates contained only aac(6′)-Il. All isolates with armA or rmtB carried group 1 or group 9 CTX-M-type β-lactamases. Among the 44 armA-positive isolates, 42 isolates expressed CTX-M-3 and 1 isolate each expressed CTX-M-14 and CTX-M-15. Among the 37 rmtB-positive isolates, 23 and 14 isolates expressed CTX-M-14 and CTX-M-3, respectively (Table 3). Among all these amikacin-resistant isolates with either individual or a combination of two resistance-conferring genes, the amikacin MICs ranged from 32 to ≥64 μg/ml. Among 20 hospitals participating in the surveillance, 17 hospitals located in all four regions contributed strains with 16S rRNA methylase-mediated amikacin-resistant ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates (Table 3). Forty-four armA-positive isolates were collected from 16 hospitals, with 11 isolates being from six northern hospitals, 15 isolates being from four southern hospitals, 17 isolates being from five western hospitals, and 1 isolate being from an eastern hospital. Thirty-seven rmtB-positive isolates were detected in 12 hospitals, whereas 16 isolates were from six northern hospitals, 20 isolates were from five western hospitals, and 1 isolate was from a southern hospital (Table 3). No rmtB-positive isolate was found in an eastern hospital. Eleven hospitals isolated both armA- and rmtB-carrying strains. All western hospitals participating in this surveillance had both armA- and rmtB-carrying strains. The only isolate carrying both armA and rmtB was also obtained from a hospital in the western region. ISEcp1 insertion sequences were detected upstream of the genes encoding the CTX-M enzymes in all 80 strains that also harbored either armA or rmtB. The insertions were observed at two different locations: either 42 or 127 bp upstream of blaCTX-M-3 and 42 bp upstream of the open reading frame for blaCTX-M-14 (Fig. 1). The upstream region of blaCTX-M-15 contained both the ISEcp1 and the IS26 insertion sequences. ISEcp1 was 127 bp upstream of the blaCTX-M-15 open reading frame, and IS26 flanked a partially truncated ISEcp1. The length of the disrupted ISEcp1 was 555 bp.

TABLE 3.

Distribution among the hospital regions of 102 ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates according to their amikacin resistance gene and coexisting ESBL genes

| Gene (no. of isolates) | Coexisting ESBL(s) | No. of isolates at hospitals in the following regions of Taiwan:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North (6)a | West (5) | South (5) | East (1) | ||

| armA (44) | CTX-M-3 | 8 | 15 | 10 | 1 |

| CTX-M-3 + SHV-5 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 0 | |

| CTX-M-14 + SHV-12 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| CTX-M-15 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| rmtB (37) | CTX-M-3 | 7 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| CTX-M-3 + SHV-12 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |

| CTX-M-14 | 7 | 14 | 0 | 0 | |

| CTX-M-14 + SHV-12 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| armA + rmtB (1) | CTX-M-3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| rmtB + aac(6′)-Il (3) | CTX-M-3 + SHV- 12 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| CTX-M-14 + CMY-2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| aac(6′)-Il (6) | CTX-M-14 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| CTX-M-14 + SHV-12 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| CTX-M-3 + SHV-12 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| SHV-12 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

The values in parentheses indicate the number of hospitals in that region.

FIG. 1.

Gene arrangement between ISEcp1 and blaCTX-M or IS26 and blaCTX-M genes from 80 armA- or rmtB-positive K. pneumoniae isolates.

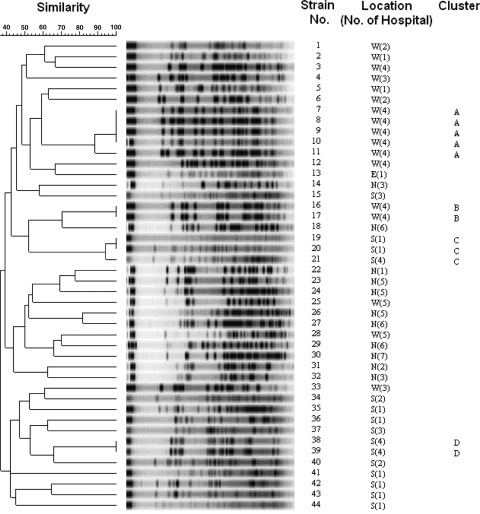

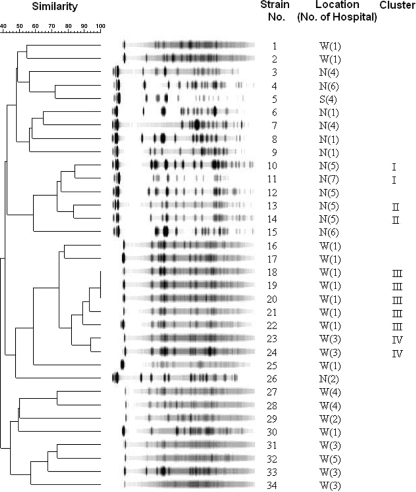

PFGE analysis.

In order to characterize the clonality of all armA- and rmtB-positive strains, we performed molecular typing. Forty-four armA-positive isolates were all typeable by PFGE. PFGE analysis revealed that four small clusters of isolates were clonally related (Fig. 2). The first cluster comprised five strains (type A), and the second cluster comprised two strains (type B), with both types being isolated from the same hospital in the western region. The third cluster comprised three strains (type C) from two hospitals, and the fourth cluster comprised two strains (type D) from one hospital in the southern region. The other 32 armA-positive isolates had distinct PFGE patterns. Of the 37 rmtB-positive strains, 34 isolates were typeable by PFGE and 3 were nontypeable. Four small clusters of isolates were clonally related (Fig. 3). The first cluster (type I) and the second cluster (type II) comprised two strains each from two different hospitals in the northern region. The third cluster comprised five strains (type III), and the fourth cluster comprised two strains (type IV); all seven strains in the third and fourth clusters were from the same hospital in the western region. The other 23 isolates had distinct PFGE patterns. These data indicate that the high prevalence of armA- and rmtB-positive isolates was not caused by clonal dissemination.

FIG. 2.

PFGE of XbaI-digested genomic DNA from 44 armA-positive ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates. Locations: W, west; N, north; S, south; and E, east.

FIG. 3.

PFGE of XbaI-digested genomic DNA from 34 rmtB-positive ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates. Locations: W, west; N, north; S, south; and E, east.

Conjugation and plasmid restriction enzyme digestion profile.

The conjugation of the ESBL resistance determinant was carried out for all 102 amikacin-resistant strains. In all 102 strains, the ESBL resistance determinant was conjugatively transferable. Amikacin resistance was found to be cotransferred with the ESBL resistance determinant in all strains. All the ESBL transconjugants contained both the CTX-M-type ESBL and a 16S rRNA methylase (armA or rmtB) gene. The resistance of 16 isolates with mechanisms of amikacin resistance not related to the presence of armA, rmtB, or the aminoglycoside-modifying enzyme within the conserved region were also found to be conjugatively transferrable, implicating plasmid-mediated resistance.

In order to clarify whether the dissemination of a specific plasmid had occurred among the isolates, we performed plasmid restriction enzyme digestion with transconjugants carrying armA or rmtB. Twenty-two armA-bearing transconjugants and 19 rmtB-bearing transconjugants were randomly selected for EcoRI digestion according to their distinct PFGE patterns. All except two of the isolates with plasmids carrying armA or rmtB had different restriction patterns; two isolates with rmtB had the same plasmid digestion profile (data not shown). These two isolates were collected from the same hospital, suggesting that the spread of a small plasmid had occurred in the hospital. The results obtained from the plasmid digestion profiles confirmed that the dissemination of armA- and rmtB-positive isolates was not likely caused by the widespread dissemination of a plasmid.

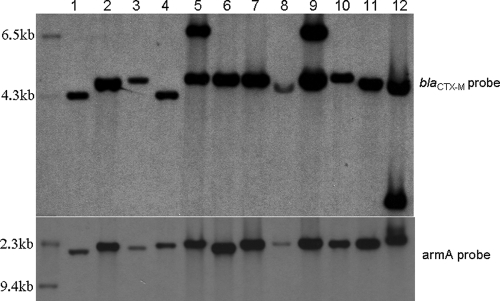

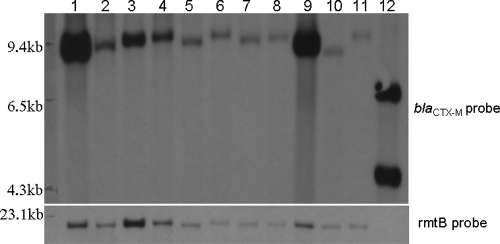

Southern blot hybridization with probes specific for blaCTX-M, armA, and rmtB.

With 12 randomly selected armA-positive isolates, we hybridized blaCTX-M- and armA-specific probes with EcoRI-digested plasmids (Fig. 4). With the armA-specific probe, we observed a single band, whereas with the blaCTX-M-specific probe we observed two bands in three isolates, indicating that two blaCTX-M genes or tandem repeats of blaCTX-M occurred in these isolates.

FIG. 4.

Southern blot hybridization of EcoRI-digested transconjugant plasmid with a digoxigenin-labeled armA- or blaCTX-M-specific probe for armA-positive isolates.

Among 11 randomly selected rmtB-positive isolates and one isolate that was specifically selected due to the coexistence of armA and rmtB, hybridization of the EcoRI-digested transconjugants with rmtB-specific probes gave a single band for all isolates except the isolate which had both armA and rmtB (Fig. 5). This isolate gave a positive signal with the armA-specific probe and double bands with the CTX-M-specific probe but did not give a positive signal with the rmtB-specific probe. Hybridization assays with probes specific for armA, rmtB, and blaCTX-M and EcoRI-digested plasmids revealed that these genes were located in plasmids of different molecular weights, implicating the spread of nonidentical plasmids among armA- and rmtB-bearing isolates.

FIG. 5.

Southern blot hybridization of EcoRI-digested transconjugant plasmid with a digoxigenin-labeled rmtB- or blaCTX-M-specific probe for rmtB-positive isolates.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we observed a high prevalence of ESBL-producing strains of K. pneumoniae resistant to both gentamicin (87.2%) and amikacin (43.4%). Previous studies on the mechanisms of aminoglycoside resistance have shown the production of aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes, including (i) aminoglycoside acetyltransferases, (ii) aminoglycoside phosphotransferases, and (iii) aminoglycoside adenylyltransferases, to be the primary mechanism of resistance. However, any one of these enzymes alone cannot confer resistance to all aminoglycosides because of their narrower substrate specificities. Because gentamicin-modifying enzymes have poor activity against amikacin and because amikacin was developed from kanamycin to block the access of a variety of kanamycin-modifying enzymes to their target sites, a relatively low prevalence of amikacin resistance is usually observed among members of the family Enterobacteriaceae (14). Among the various aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes, acetyltransferases [AAC(6′)-I and AAC(6′)-APH(2″)], adenylyltransferases [ANT(4′)-I and ANT(4′)-II], and phosphotransferases [APH(3′)-II and APH(3′)-III] have been shown to result in the modification of amikacin (25). In our study, only 9 (8.8%) isolates contained the aac(6′)-Il gene that contributed to the observed amikacin resistance. Since there were 16 isolates with amikacin resistance which was not caused by an aminoglycoside-modifying enzyme whose sequence was located within the conserved region, the genes for other aminoglyglycoside-modifying enzymes conferring amikacin resistance require further study. Nonetheless, the incidence of amikacin resistance among our ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates was high in comparison with the incidences determined from data obtained from Canada, Europe, Latin America, the United States, and the Western Pacific region, which had resistance rates of 5.6%, 54.2%, 66.1%, 11.1%, and 37.7%, respectively (28).

Since the first report of the armA 16S rRNA methylase gene, which was responsible for plasmid-mediated amikacin resistance in a clinical K. pneumoniae isolate from France (9), other genes for 16S rRNA methylases, such as armA and rmtB, on plasmids have subsequently been documented in Europe and East Asia (1, 7, 29). In Taiwan, plasmid-borne armA and rmtB genes have been identified in aminoglycoside-resistant E. coli and K. pneumoniae isolates in two hospitals (29). In contrast to the findings of a previous study performed in Taiwan, which showed a predominance of armA carriers with an approximately 50% transfer frequency (29), and the finding of the nontransfer of rmtB plasmids by Doi et al. (7), all isolates with armA or rmtB in our study were conjugatively transferable together with either group 1 (CTX-M-3 and CTX-M-15) or group 9 (CTX-M-14) CTX-M genes. One intriguing finding is that only armA and blaCTX-M were detected in the transconjugant from the isolate carrying both armA and rmtB, indicating that rmtB is not located on the same conjugatively transferable plasmid.

Among the 44 armA-positive isolates, 32 distinct PFGE patterns were found, and 42 isolates concomitantly harbored the CTX-M-3 gene. Among the 37 rmtB-positive isolates, 23 distinct PFGE patterns were detected. Only small numbers of isolates with armA or rmtB were clonally related. The results obtained by PFGE implicated the nonclonal spread of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae strains with armA- or rmtB-mediated aminoglycoside resistance.

A recent review has shown that CTX-M type β-lactamases have disseminated worldwide to become a problem with a global magnitude, with an especially high prevalence among isolates of the family Enterobacteriaceae (23). At present, CTX-M enzymes are subclassified into six groups (23). The origin of group 1 CTX-M was Kluyvera ascorbata (22), and that of group 9 CTX-M was Kluyvera georgiana (3). The appearance of two different groups of CTX-M-bearing strains with armA or rmtB among our isolates suggested that blaCTX-M was captured by independent events. Furthermore, the great diversity of patterns of the plasmid restriction fragments suggests the wide dissemination of plasmid-mediated armA or rmtB via uncertain mechanisms. Recently, researchers have verified that the rapid emergence and worldwide spread of these plasmid-mediated enzymes are possibly associated with insertion sequences ISEcp1 and ISCR1 (2, 3, 18). In our study, ISEcp1 was detected upstream of the blaCTX-M gene, along with armA or rmtB, suggesting that the presence of ISEcp1 may contribute to the high prevalence of CTX-M in Taiwan, leading to comobilization of the plasmid-mediated armA and rmtB genes. An intriguing finding is that the location of ISEcp1 upstream of blaCTX-M is CTX-M type specific. Whether the insertion is sequence specific will require clarification in the future.

In this survey, the proportion of isolates carrying armA (43%) and rmtB (36%) among all amikacin-resistant isolates was not substantially different. Southern hybridization of a random selection of 11 armA-positive isolates from different regions and hospitals in Taiwan and 1 isolate carrying both armA and rmtB showed that three EcoRI-digested plasmids from armA carriers that hybridized with the blaCTX-M-specific probe presented double signals (Fig. 5). The presence of two copies of blaCTX-M due to the presence of two different plasmids was considered unlikely because only one large plasmid was identified in all three transconjugants (data not shown). Although the armA gene has been reported to be linked with blaCTX-M (10), the linkage of the presence of blaCTX-M and rmtB was also observed in this study.

In conclusion, the present surveillance revealed a high prevalence of 16S rRNA methylase genes among blaCTX-M-type ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates in Taiwan. The involvement of ISEcp1 in the mobilization of CTX-M genes with other resistance determinants needs to be monitored closely.

Acknowledgments

We thank the following hospitals (in alphabetical order) participating in the Taiwan Surveillance for Antimicrobial Resistance (TSAR) project for supplying the ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae strains: in the northern region, Far Eastern Memorial Hospital, Heping Hospital, Lo-Tung Poh Ai Hospital, MinSheng General Hospital, St. Mary's Hospital Lotung, Tri Service General Hospital, and ZhongXiao Hospital; in the western region, Chang-Hua Christian Hospital, Cheng Ching Hospital, Kuan-Tien General Hospital, Veterans General Hospital—Taichung, and Zen Ai General Hospital; in the southern region, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital at Kaohsiung, Chiayi Christian Hospital, Kaohsiung Medical College Chung-Ho Memorial Hospital, National Cheng Kung University Hospital, SinLao Hospital, and Veterans General Hospital-Kaohsiung; and in the eastern region, Hua-Lien Hospital and Hua-Lien Mennonite Church Hospital.

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Science Council (grant NSC 95-2314-B-016-013) and the National Health Research Institutes.

We have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 20 October 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bogaerts, P., M. Galimand, C. Bauraing, A. Deplano, R. Vanhoof, M. R. De, H. Rodriguez-Villalobos, M. Struelens, and Y. Glupczynski. 2007. Emergence of ArmA and RmtB aminoglycoside resistance 16S rRNA methylases in Belgium. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 59:459-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonnet, R. 2004. Growing group of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases: the CTX-M enzymes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canton, R., and T. M. Coque. 2006. The CTX-M beta-lactamase pandemic. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9:466-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2006. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard M7-A7. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA.

- 5.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2007. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 17th informational supplement M100-S17. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA.

- 6.D'Agata, E. M., M. M. Gerrits, Y. W. Tang, M. Samore, and J. G. Kusters. 2001. Comparison of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and amplified fragment-length polymorphism for epidemiological investigations of common nosocomial pathogens. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 22:550-554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doi, Y., K. Yokoyama, K. Yamane, J. Wachino, N. Shibata, T. Yagi, K. Shibayama, H. Kato, and Y. Arakawa. 2004. Plasmid-mediated 16S rRNA methylase in Serratia marcescens conferring high-level resistance to aminoglycosides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:491-496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eckert, C., V. Gautier, M. Saladin-Allard, N. Hidri, C. Verdet, Z. Ould-Hocine, G. Barnaud, F. Delisle, A. Rossier, T. Lambert, A. Philippon, and G. Arlet. 2004. Dissemination of CTX-M-type beta-lactamases among clinical isolates of Enterobacteriaceae in Paris, France. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1249-1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galimand, M., P. Courvalin, and T. Lambert. 2003. Plasmid-mediated high-level resistance to aminoglycosides in Enterobacteriaceae due to 16S rRNA methylation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:2565-2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galimand, M., S. Sabtcheva, P. Courvalin, and T. Lambert. 2005. Worldwide disseminated armA aminoglycoside resistance methylase gene is borne by composite transposon Tn1548. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:2949-2953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gallego, L., and K. J. Towner. 2001. Carriage of class 1 integrons and antibiotic resistance in clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii from northern Spain. J. Med. Microbiol. 50:71-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kado, C. I., and S. T. Liu. 1981. Rapid procedure for detection and isolation of large and small plasmids. J. Bacteriol. 145:1365-1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klingenberg, C., A. Sundsfjord, A. Ronnestad, J. Mikalsen, P. Gaustad, and T. Flaegstad. 2004. Phenotypic and genotypic aminoglycoside resistance in blood culture isolates of coagulase-negative staphylococci from a single neonatal intensive care unit, 1989-2000. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 54:889-896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kondo, S., and K. Hotta. 1999. Semisynthetic aminoglycoside antibiotics: development and enzymatic modifications. J. Infect. Chemother. 5:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Korvick, J. A., C. S. Bryan, B. Farber, T. R. Beam, Jr., L. Schenfeld, R. R. Muder, D. Weinbaum, R. Lumish, D. N. Gerding, and M. M. Wagener. 1992. Prospective observational study of Klebsiella bacteremia in 230 patients: outcome for antibiotic combinations versus monotherapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 36:2639-2644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee, H., D. Yong, J. H. Yum, K. H. Roh, K. Lee, K. Yamane, Y. Arakawa, and Y. Chong. 2006. Dissemination of 16S rRNA methylase-mediated highly amikacin-resistant isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Acinetobacter baumannii in Korea. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 56:305-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nemec, A., L. Dolzani, S. Brisse, P. van den Broek, and L. Dijkshoorn. 2004. Diversity of aminoglycoside-resistance genes and their association with class 1 integrons among strains of pan-European Acinetobacter baumannii clones. J. Med. Microbiol. 53:1233-1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Novais, A., R. Canton, A. Valverde, E. Machado, J. C. Galan, L. Peixe, A. Carattoli, F. Baquero, and T. M. Coque.2006. Dissemination and persistence of blaCTX-M-9 are linked to class 1 integrons containing CR1 associated with defective transposon derivatives from Tn402 located in early antibiotic resistance plasmids of IncHI2, IncP1-alpha, and IncFI groups. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:2741-2750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paterson, D. L. 2000. Recommendation for treatment of severe infections caused by Enterobacteriaceae producing extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs). Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 6:460-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paterson, D. L., W. C. Ko, A. Von Gottberg, S. Mohapatra, J. M. Casellas, H. Goossens, L. Mulazimoglu, G. Trenholme, K. P. Klugman, R. A. Bonomo, L. B. Rice, M. M. Wagener, J. G. McCormack, and V. L. Yu. 2004. Antibiotic therapy for Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia: implications of production of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 39:31-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Preheim, L. C., R. G. Penn, C. C. Sanders, R. V. Goering, and D. K. Giger. 1982. Emergence of resistance to beta-lactam and aminoglycoside antibiotics during moxalactam therapy of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 22:1037-1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodriguez, M. M., P. Power, M. Radice, C. Vay, A. Famiglietti, M. Galleni, J. A. Ayala, and G. Gutkind. 2004. Chromosome-encoded CTX-M-3 from Kluyvera ascorbata: a possible origin of plasmid-borne CTX-M-1-derived cefotaximases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:4895-4897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rossolini, G. M., M. M. D'Andrea, and C. Mugnaioli. 2008. The spread of CTX-M-type extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 14(Suppl. 1):33-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 24a.Sanger, F., S. Nicklen, and A. R. Coulson. 1977. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74:5463-5467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaw, K. J., P. N. Rather, R. S. Hare, and G. H. Miller. 1993. Molecular genetics of aminoglycoside resistance genes and familial relationships of the aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes. Microbiol. Rev. 57:138-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siu, L. K., P. L. Ho, K. Y. Yuen, S. S. Wong, and P. Y. Chau. 1997. Transferable hyperproduction of TEM-1 beta-lactamase in Shigella flexneri due to a point mutation in the Pribnow box. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:468-470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tenover, F. C., R. D. Arbeit, R. V. Goering, P. A. Mickelsen, B. E. Murray, D. H. Persing, and B. Swaminathan. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2233-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winokur, P. L., R. Canton, J. M. Casellas, and N. Legakis. 2001. Variations in the prevalence of strains expressing an extended-spectrum beta-lactamase phenotype and characterization of isolates from Europe, the Americas, and the Western Pacific region. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32(Suppl. 2):S94-S103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yan, J. J., J. J. Wu, W. C. Ko, S. H. Tsai, C. L. Chuang, H. M. Wu, Y. J. Lu, and J. D. Li. 2004. Plasmid-mediated 16S rRNA methylases conferring high-level aminoglycoside resistance in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from two Taiwanese hospitals. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 54:1007-1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]